ICE HOCKEY ARENA FOR MILAN-CORTINA 2026 OLYMPICS

PROPOSAL FOR A NEW MULTI FUNCTIONAL ARENA IN SANTA GIULIA

MASTER DEGREE THESIS IN BUILDING ARCHITECTURE

POLITECNICO DI MILANO

SCUOLA DI ARCHITETTURA, URBANISTICA E INGEGNERIA DELLE COSTRUZIONI

AUTHORS:

JÚLIO HERMINIO BRESSAN MARTINS

935922

ERIC THOMAS LAUGHLIN LARA

941628

ELIO ZEIATER NASSAR

940192

SUPERVISOR:

PROF. MARIA GRAZIA FOLLI | ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

IN INTEGRATION WITH:

PROF. GIOVANNI DOTELLI | INNOVATIVE MATERIALS FOR ARCHITECTURE

PROF. MARCO IMPERADORI | TECHNOLOGY AND DESIGN IN BIM ENVIRONMENT

PROF. CORRADO PECORA | STRUCTURAL DESIGN

PROF. FRANCESCO ROMANO | BUILDING SERVICES DESIGN

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As a group we would like to thank primarily the support of our professors which followed the development of this project with dedication and patience. Namely, Professors Giovanni Dotelli, Marco Imperadori, Corrado Pecora, Francesco Romano, and, overall, our advisor Professor Maria Grazia Folli.

We would like also to thank the support of professionals that gave us fundamental critics and knowledge during the development of our design. Namely, Dr. Fabio Bianchetti, Mr. Peter Krick and Eng. Tomaso Pagnacco.

Finally, we would like to thank the support of our beloved family, partners, and friends, whose unconditional support gave us the motivation and means to finish the academic cycle successfully.

ABSTRACT

Le Olimpiadi Invernali Milano-Cortina 2026 sono un’opportunità unica per le regioni del nord Italia di dimostrare un potenziale logistico di livello mondiale. Con questo prossimo evento ci sono molteplici sfide, tra cui la costruzione di strutture e la realizzazione e il potenziamento delle infrastrutture sono di alta priorità. Siamo giunti a una proposta che soddisfa gli obiettivi per il futuro in rapida evoluzione e dà una nuova eredità olimpica alla città di Milano. Il progetto qui presentato è di per sé un dispositivo versatile che grazie a implementazioni altamente tecnologiche può ospitare diverse aree di sport e intrattenimento, e una ricca quantità di spazio in grado di ospitare una varietà di funzioni in relazione diretta con l’ambiente circostante. Il percorso principale che collega queste funzioni è legato alla tradizione architettonica milanese dello “spazio di mezzo”, ed è la vena distributiva dell’edificio, che collega l’anello funzionale esterno e l’area dedicata agli eventi. Questo spazio è coperto da un polimero traslucido, leggero, ma ad alte prestazioni per dare una luce più diretta a questo corridoio. L’area dell’hockey e del pattinaggio su ghiaccio è coperta da una struttura estremamente leggera che, attraverso la traslucenza, consente a una nebbia di luce naturale di entrare nello spazio durante il giorno e offre agli estranei uno sguardo sulla situazione che si verifica di notte. Queste aree possono essere modificate grazie a una configurazione meccanica di catene rigide che controlla le dimensioni dell’arena, dando spazio a più posti. La combinazione di tutti questi elementi strutturali grezzi, non strutturali e meccanici crea una composizione che mira a una lunga vita e sopporta le sfide future di Milano e del mondo in continua evoluzione dell’umanità.

PAROLE CHIAVE: Olimpiadi Invernali Milano-Cortina, Ice Hockey Arena, Multi Functional Arena, Rigenerazione Urbana, Tension Structures

ABSTRACT

The Milan-Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics are a unique opportunity for the northern Italian regions to demonstrate a world-class logistical potential. With this upcoming event there are multiple challenges, from which the construction of structures and implementation and enhancement of infrastructures are of high priority. We have come to a proposal, that meets the goals for the fast-changing future and gives a new Olympic legacy to the city of Milan.

The project here presented is itself is a versatile device that due to highly technological implementations can host different areas of sports and entertainment, and a rich quantity of space capable to host a variety of functions in direct relations to its surroundings. The main path connecting these functions relates to the Milanese architectural tradition of the “space in between”, and is the distributive vein of the building, that connects the outer functional ring and the area dedicated to the events. This space is covered by a translucent, light, yet high performance polymer to give a more direct light to this corridor. The ice hockey and ice skating area are covered by an extremely light structure that through translucency permits a mist of natural light enter the space during the day, and gives to outsiders a glance of the situation there happening at night. These area may be possible to be changed due to a mechanical configuration of rigid chains that controls the size of the arena, giving room to more seats. The combination of all these structural rough, nonstructural and mechanical elements create a composition that aims for a long lifetime and endure the future challenges of Milan, and of humanity’s ever changing world.

KEY WORDS: Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics, Ice Hockey Arena, Multi Functional Arena, Urban Regeneration, Tension Structures

INTRODUCTION

FIRST AND FOREMOST

Milan is the most populous city in Italy and the country’s main industrial, financial, and commercial center, with Borsa Italiana (Italy’s main stock exchange) and the headquarters of the large national and international banks located in the city. Milan is also a major capital of fashion and design in the world and is well known for several international events and fairs, such as Milan Fashion Week and Milan Design week, to name but a few. In 2015, Milan hosted the Expo 2015, which helped in further stimulating the city’s economy with a number of developments still under construction across the city. Milano Santa Giulia, currently under development and only 15 minutes southeast of Downtown Milan, is a whole new city quarter, and has been called Milan’s most innovative city district of the future.

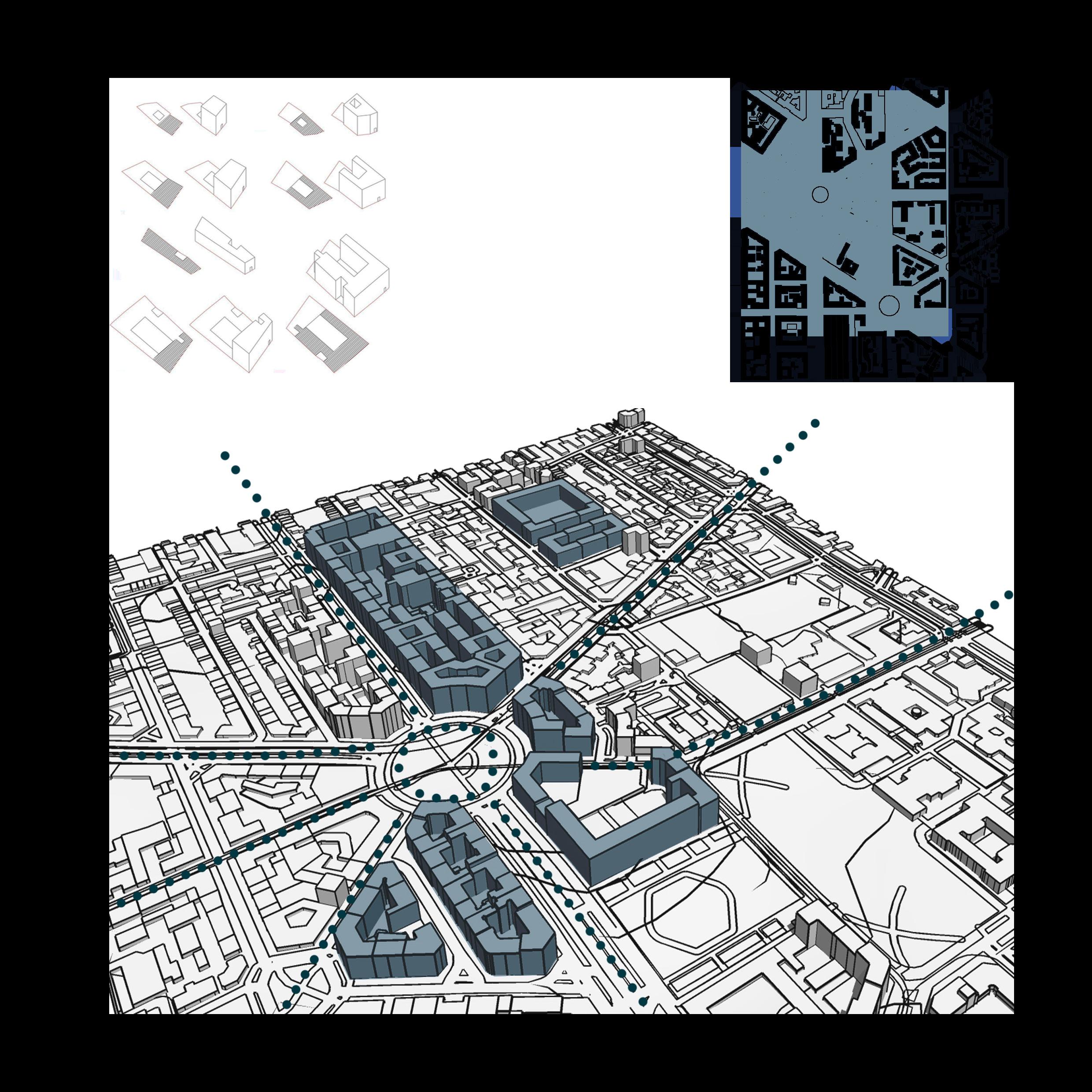

Milano Santa Giulia, which was known as an area of industrial character since the late 19th century, is located between 2 districts: Rogoredo and Taliedo. In recent decades, these industrial factories either changed their location or have closed, especially Montedison factory and the Redaelli steel mills. Such closure or change in location have left a huge gap in the urban fabric of Santa Giulia. Different reforms and urban regeneration plans were planned for the area, but it wasn’t until developer company Risanamento Spa bought the land and those plans started to become a reality. Risanamento hired an international architecture firm; Fosters & Partners, for the overall concept and masterplan, and the Design International architecture firm were asked as well to design the retail

sectors of Milano Santa Giulia which are the commercial and communal center of the new city district.

And that is where our part interferes, following Foster’s master plan proposal, many criteria and critical elements were highlighted and defined in the proposed masterplan. And for this reason, different aspects needed to be re-considered, enhanced, and improved, specially the linking connection between the different zoning areas and interaction between different sectors and their communal effect. Moreover, the main point of our thesis project is Milano’s Santa Giulia Sport Hall, which is designed for Milan’s 2026 Winter Olympics. Our structure was created via extensive study, design, and the various technological components that are integrated into the structure, such as structural design, material selection, and construction efficiency in terms of modularity and sustainability. Follow such order, our thesis is derived and presented in such chronology. Prior to begin with the building’s approach and design, let us explore Milan’s urban history first, to better understand the contextual effect and the role that building plays in the urban context.

URBAN HISTORY

URBAN HISTORY

FROM MEDIOLANUM TO MILAN – EVOLUTION OF MILAN’S URBAN PLANNING AND MORPHOLOGY

Due to its strategic location, being placed on the north of Italy with a close relation to various parts of Europe, Milan and the region of Lombardy in general have been subjects of several battles over the centuries. Different population ruled the city at different times, starting from the Celts, which are the ones who founded Milan, to Romans, Goths, and Lombards, to Spaniards and Austrians. As mentioned, due to its position, Milan has emerged as an undisputed economic and cultural powerhouse, playing a major role in shaping Italy’s economy and innovation.

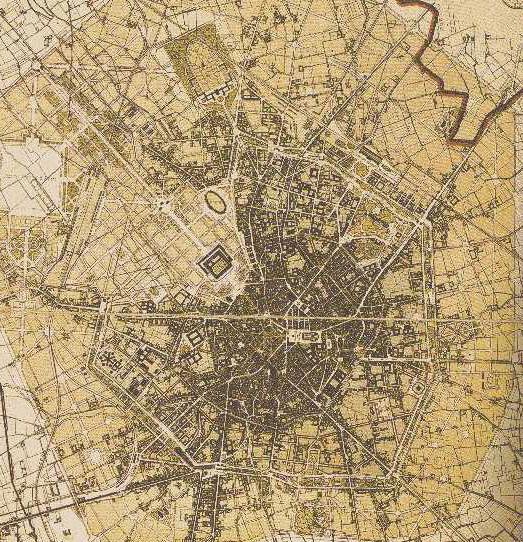

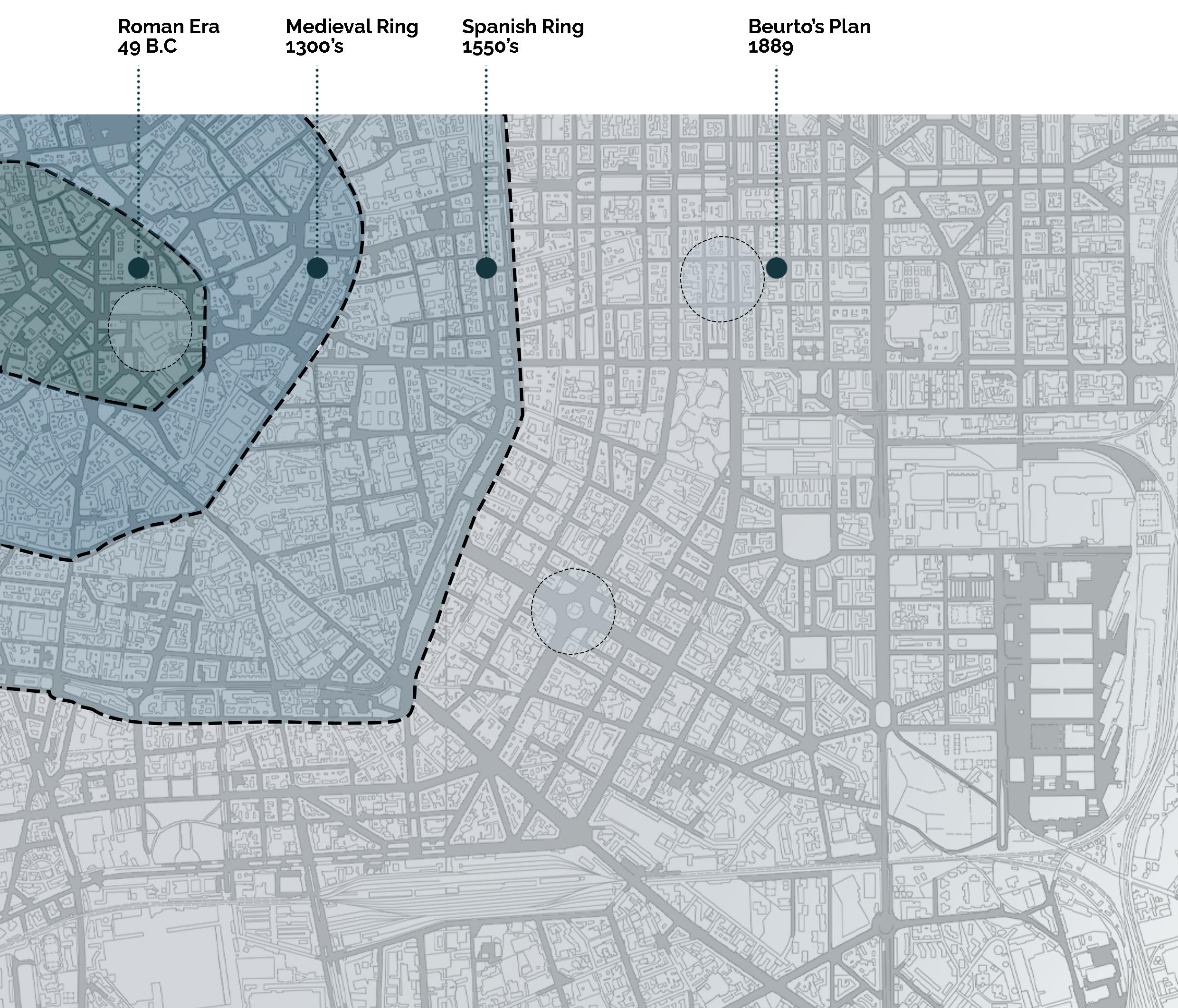

Looking at Milan’s mass plan, we can clearly identify the system of rings and circular defending walls which were built throughout different ages and centuries. While virtually little of these walls exist, their structure is mirrored in the city’s urbanistic layout. The oldest are the Roman walls, which were developed in 2 stages, the first in the Republican (49 B.C) and the second in the Imperial era (305 B.C).

Fast forwarding into history to the 12th century, we can clearly realize the limit of Milan’s walls during the Medieval age which were built as a defense against raids, to which today, several remnants remain, such as Porta Ticinese, Porta Nuova, remnants of the medieval Porta Romana…etc. These walls formed what is known today as “Cerchia dei Navigli”.

The third defending wall in Milan’s history dates back to 15th century, which was built during the Spanish rule of Milan, known as the “Mura Spagnole” (Spanish Wall). Such wall system was of about 11 km, much longer than that of the medieval fortifications. The perimeter of the Spanish walls essentially corresponds to what is now known as the “Cerchia dei Bastioni” (“Bastion Ring”).

To understand the evolution of Milan, it was necessary that we present and discuss Milan’s history and the effect these rings have had over the years. Despite the change of urban morphology, we can still see the ruins of the city’s most important monuments and several gates that have had an influence and significance to this day. However, the urban growth of the city which kept on spreading, led to the demolishing of these walls, leaving only part of them preserved until today serving as part of city’s heritage. Subsequently, the city expanded indefinitely, starting from the center branching out thanks to Beruto’s plan, forming a neverending-spread city, just a like a drop of oil which continuously spreads along.

Following numerous disputes and strong pressure that have arisen, an opportunity was seized to carry out a vast project that, which would solve various problems such as the area around Sforzesco Castle, but in a broader perspective. Moreover, due to the continuous need to create passages from the Spanish walls’ ring which was constituting a real barrier between the historic city and the surrounding territories, peripheral areas which were progressively transforming into industrial areas, Beruto was assigned and commissioned to prepare the first urban planning tool of the city.

RADIAL/LINEAR GRID

It wasn’t until 1889 that Beruto’s plan was approved, a plan that is still today one of the events in the urban history of Milan that has profoundly marked its destiny. Such plan concluded the destruction of the Spanish walls, and another ring was created which delimits the maximum expansion of the city. The main axes that converge toward the historic center were extended and projected towards the territories, and such expansion strip obtained, was marked by regular network of streets and squares. Large blocks were designed which guarantee the possibility of aligning the frontal facades of the building with the streets and creating internal courtyards, marking a Milanese building morphology. As the city expanded and new urban plans were proposed, different morphologies and neighborhoods designs’ approaches were observed, marking the evolution of Milan and new era for urbanistic planning for the city.

As well as, as the city expanded, different city grids and morphologies were observed. Starting from the Roman era,even during the Medieval and Spanish times, the city streets were often organic without a defined strategy. With the introduction of Beruto’s plan, that changed, allowing for continuous connections between districts through a linear grid street with a round-about for division and spread of differents nerves within the area. This will allow for never ending spread for the city of Milan, consisting of streets continuously connected.

MORPHOLOGY

MORPHOLOGY

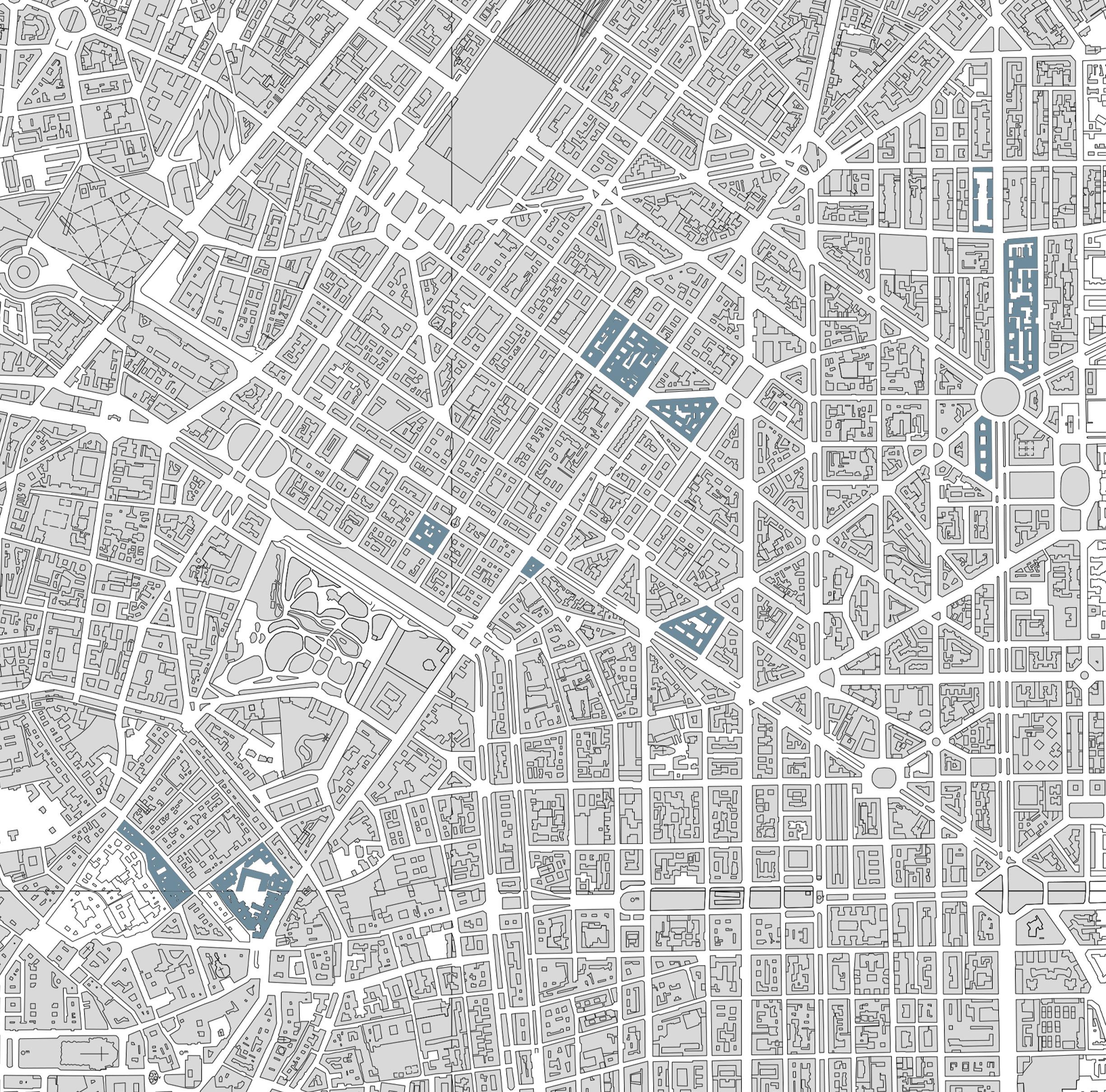

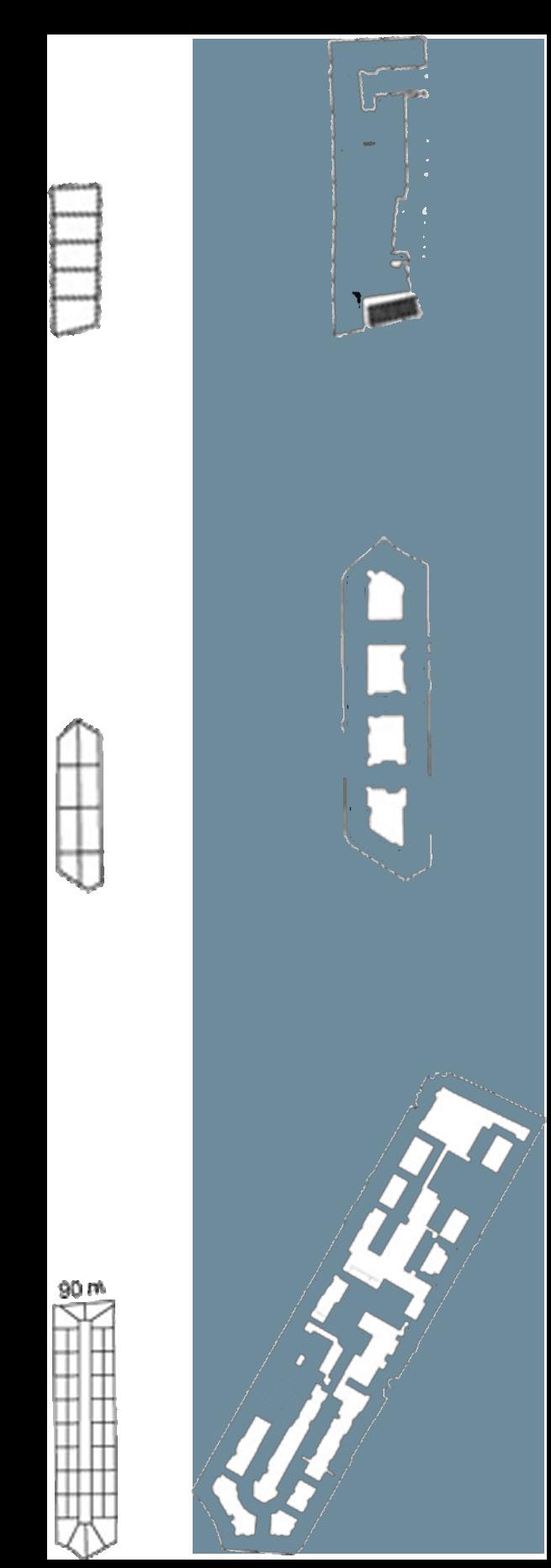

INTRODUCTION

To better understand the typology of Milan and how the city has been formed architecturally and how it has evolved, we had to carefully study the progression and advancement of the relation between built and unbuilt spaces. The investigation included emphasizing specific lots, identifying different construction typologies, and examining the relationships between built spaces, as well as between buildings, streets, and interior courtyards. Such classification and categorization is an important element in our thesis to better understand the city. Such research helps to outline more broad and fundamental concerns, such as the link between constructed and unbuilt city areas, and so contributes to the project’s process.

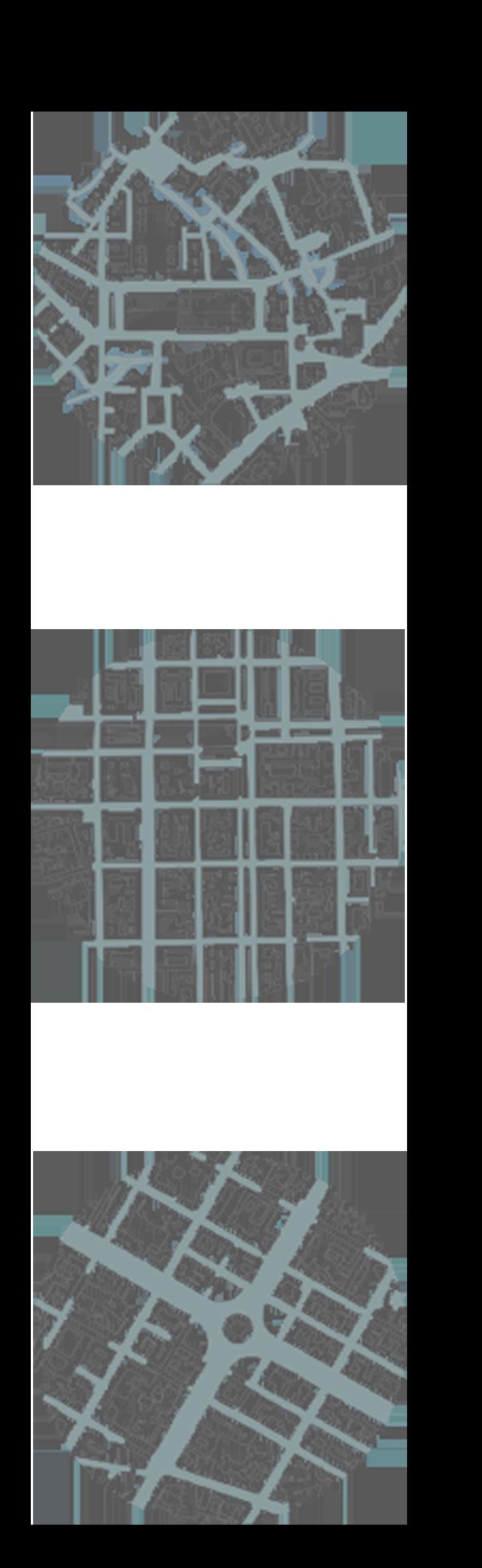

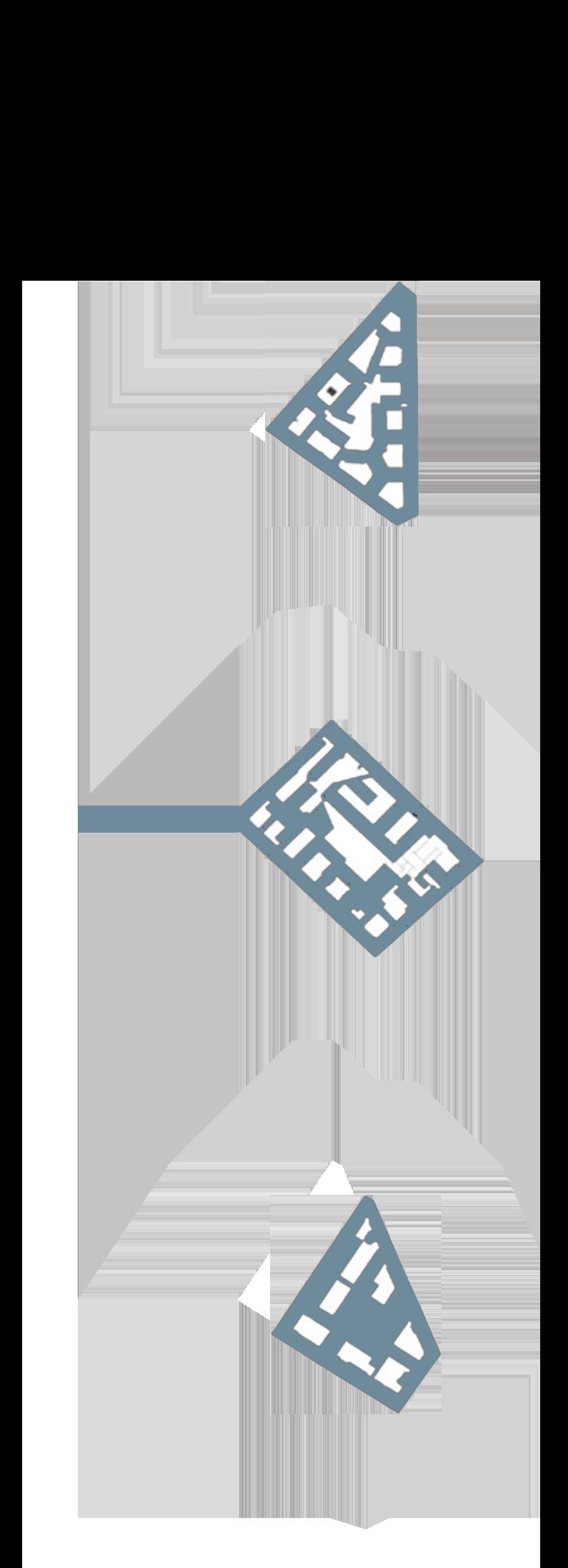

ANALYSIS OF THE BLOCKS | FORM-BASED CLASSIFICATION

The shape of Milan’s old center’ blocks is the consequence of many and distinct plans overlapping, resulting in several types of districts. In recent parts of the city, the resulted blocks and shapes are derived from the planning process. In particular, we can observe the resulting in triangular and trapezoidal form of blocks, and that’s due from the urban fabric consisting of radial streets and round piazzas, which was drawn by the 19th century planner of the city, Cesare Beruto.

The purpose of this categorization is to emphasize how both urban changes and planning activities influence the shape of Milanese urban blocks.

ANALYSIS OF THE BLOCKS | PER-PARCEL CLASSIFICATION

SINGLE-PARCEL BLOCK

We expand on our research to show how the aggregation of additional plots produced the urban Milanese blocks. Such aggregation can be sub-categorized into different subjects, one of which is the two orders of parcels, where two properties are placed one after another and the buildings are constructed on their boundaries, resulting in an open space in between. We notice as well, in certain parts of the city, the construction of several orders of parcels, with a central open courtyard, resulting in larger blocks. The aggregation idea stays the same, but what has changed is the development of larger blocks with open spaces inside them that are used as semi-public spaces or even as green areas.

• Block of buildings surrounded by open space

• Deep block of buildings

• Buildings with closed courtyards

This particular type is the most typical of the city of Milan, in which such residential and building typology is diffused and can be found in ex-industrial districts as well as in the historical center of the city. This typology is characterized by the public assets it provides through commercial centers and shops on the ground floor; however, it provides as well as a private life for the residents through the inner courtyard of the building which is characterized by different architectural elements, and it is the place that allows for the penetration and diffusion of light and it acts as a circulation element where we can find the stairs for vertical circulation.

DOUBLE-PARCEL BLOCK

MULTIPLE-PARCEL BLOCK

Courtyards: host the private life of the house and the collective or professional activities

The introduction of trapezoidal buildings following Beruto’s expanding plans.

EVOLUTION

EVOLUTION

A PATH INTO A NEW MILAN

As we look over some of Milan’s projects in the periphery, we can clearly see how the typology and morphology have evolved, and how Milan has been evolving starting in the 1960s and 1970s where the city stretched out in different forms and different concept, varying from the initial concept of attached buildings and parcels with inner courtyard to a more open, green, vast and clear spaces between one building and another.

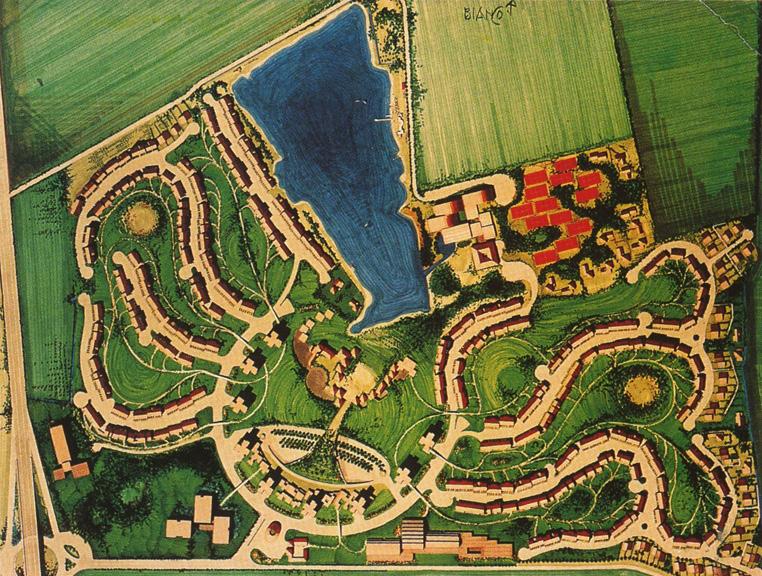

To name a few examples of how the city has evolved, we can take a look at The Sant’Ambrogio I district which was built in implementation of the PEEP of 1963 in an area without urban contextualization south of Milan, characterized by the presence of the extensive countryside of the nearby South Agricultural Park. The large lot is delimited by four long residential buildings with a sinuous course, which circumscribe within them a vast green space, strictly pedestrian, intended for services and life collective. Such complex was conceived as an introverted, protected, and self-sufficient neighborhood, yet ready for dialogue with the then expanding city.

Another example is The San Felice district, between the municipalities of Segrate, Peschiera Borromeo and Pioltello, it’s located in a ring road area to the city of Milan and represents, at the end of the 1960s, an archetype of a modern suburban neighborhood, away from traffic and chaos citizen. The masterplan, organic in its planimetric forms, presents its development pivot in the central ring road facing the Malaspina lake, which houses

the commercial services, the church and the collective spaces. The streets, with their undulating and often dead ends, host the residences arranged on a continuous curtain. The fronts are differentiated through a diversified use of architectural language: those on the street, designed to accommodate cars, are characterized by the scansion of spur walls arranged in a comb that delimit the entrances to the garages, while the internal ones, with balconies overlooking the « gulfs of green », They respond to needs closer to human needs and favor greater intimacy. At the end of the district are located the low residences of brown plaster.

Nevertheless, in the San Felice district a good formal synthesis between modernist principles and Milanese style can be recognized; moreover, it immediately becomes a reference model, for example for nearby Milano 2 (1968-1979), where the absence of a solid design culture will, however, lead to a much less interesting result from an architectural level.

The concept of “peripheral centrality” is also inspired by the Service Center at the INCIS Village (1972-1981) in Pieve Emanuele by Guido Canella, Michele Achilli and Daniele Brigidini. The dissonant tension that is established between the beefy bodies of the different “actors” called to recite around the central square (nursery and primary school, multipurpose building and parish center) translates the overall function of the center into threedimensional shapes “social condenser”,

or a place with a high identifying power in the no man’s land of the suburban territory. The integration of residential, tertiary, and commercial functions - as well as an interesting exploitation of congestion - produces a sort of “city within the city” with highly expressive values and considerable urban potential.

Above were some examples of 1960s and 1970s which clearly show how Milan’s architecture was able to rediscover itself and move on from its traditional parcel block, always parallel to street grids with closed courtyards, which were derived from the urbanistic plan of Berruto, to a more sustainable and green way of living, allowing more spaces for connection, communicating, exercising, and spaces for leisure activities. Such evolution has had a huge impact on the city of Milan and Milanese architecture which allowed lastly to reach the modern and contemporary architecture that we know today, such as Porta Nuova, CityLife, Bocconi University, just to name a few.

Such analysis was identified and done for the purpose of better understanding the origin of Milanese architecture, how it has evolved, and where it is now. Such analysis clearly shows the different parts of the city and the discontinuity of local typological processes. We performed this study in order to better design our masterplan following Milan’s latest evolvement and growth, to be in a better synchronization and better coherence with the surrounding and to design a project which suits and respects Milan’s traditional architecture and its latest evolution.

The principles and regulations by which the urban environment formed, and to which every new design must be connected, may be discovered by reconstructing the typological process. These rules govern the architecture of a building, including its type, plan, structure, façade, components, and materials, as well as its location in the urban fabric – the relationship between the building and the plot, the building and the street, and the building and its location in the street block. The more closely a development adheres to these guidelines, the more it will blend in with existing structures, laying the groundwork for future changes.

EXISTING CONTEXT OF SANTA GIULIA

EXISTING CONTEXT OF SANTA GIULIA

PREVIOUS AND CURRENT RELATION WITH THE CITY

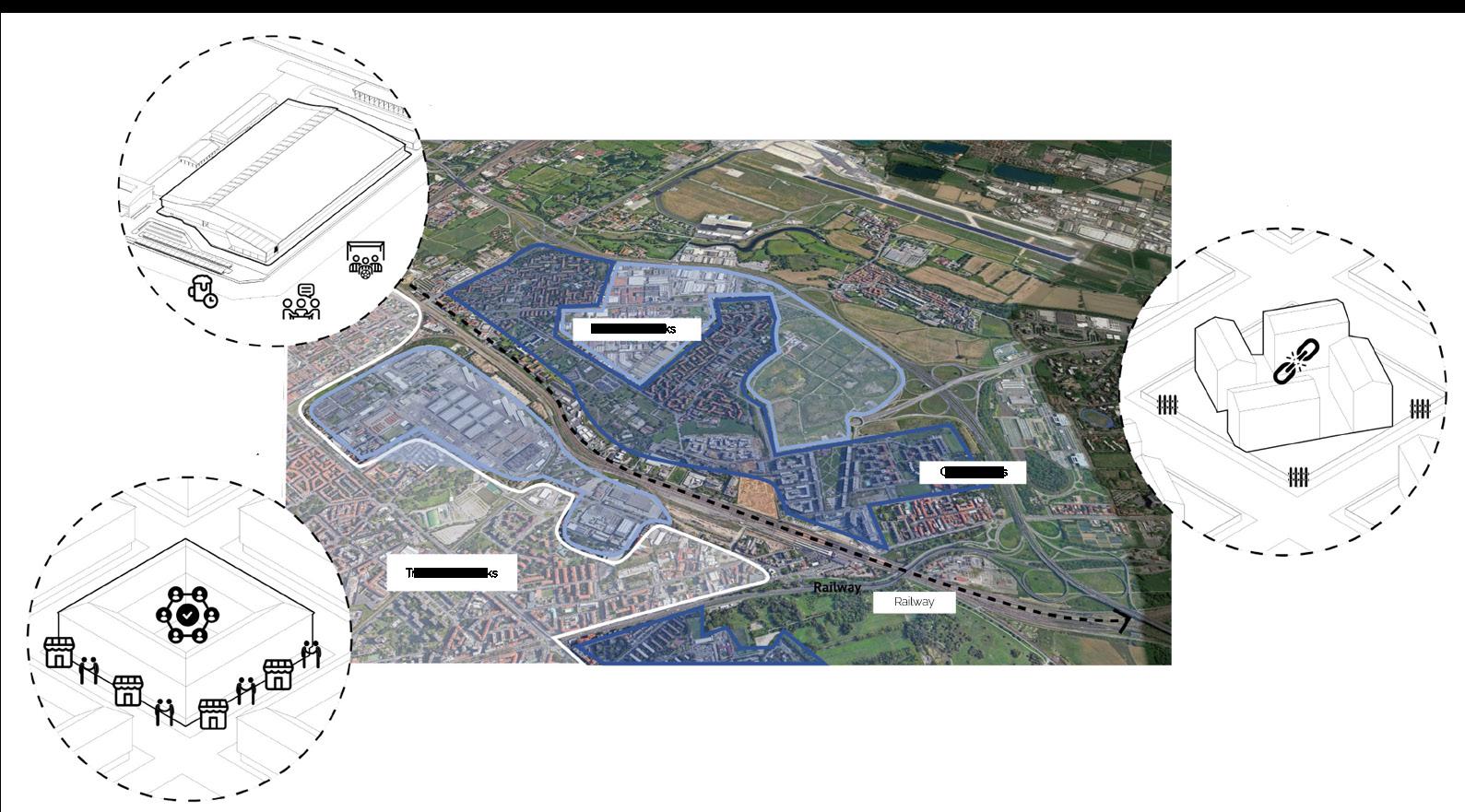

Santa Giulia area is located in the south-east of Milan. The Integrated Intervention Plan that concerns it is aimed at redeveloping a former industrial area of 120 hectares with the aim of making it the “New South Gate” of Milan. In this way it would become part of the system of large poles of public services and functions that allow for a decongestion of the city center.

Originally, Milano Santa Giulia was an agriculture village, then starting the early decades of 1900s, it witnessed the rise of industrial steel mills, in which Rogoredo’s name, apart for being a railway station, was linked to that of various Milanese industries such as Redaelli and Montecatini. Since the 1920s, the life of the neighborhood revolved around the industrial plants that largely affected the spatial, residential, and social aspect of the neighborhood. The residences were strictly inhabited by the workers of the nearby factories. Difficulty to access the area, Rogoredo remained, in part, an isolated neighborhood, away from the city and its interests. The history of Milano Santa Giulia begins with the closure of the Montedison plant, in the current northern area of the P.I.I. and the Acciaierie Redaelli, in the south-west area, adjacent to the railway. Thus, a real void was created in the urban fabric which they tried to remedy urban redevelopment plans of the territory, which considered separate interventions for the two areas.

The inverted T model is a new spatial reorganization model for the supporting urban structure proposed by the Framework Document “Rebuilding the Greater Milan” and takes shape practically from the placement of the most important urban transformations of private initiatives.

The model, which has absolutely no prescriptive value, in theory, proposes to enhance the connection of the most important urban areas at an economic/commercial/directional level, directing a large part of interests and resources (public/private) along the two development backbones. The most developed axis, the northern one of Milan-Monza, involves current realities, projecting itself towards the next business center and the City of Fashion of Garibaldi/Republica.

The most recent axis, the north-west / south-east one of Malpensa-Linate, is intended to be a new axis of international economic development, which is capable of to quickly connect the two Milanese airports.

INFRASTRUCTURAL CONTEXT

Milano Santa Giulia is well connected to Milan’s local urban infrastructures, and it also has access to a larger national and international transit network. Linate airport, which is Milan’s primary airport for short-haul international and domestic flights, is 10 minutes away by car, which is considered relatively closed and optimal for Santa Giulia, allowing it to design a commercial, residential, and sport-related masterplan. Another strong connection point for such area is Autostrada 51 (A51) which is one of Italy’s main arteries, connecting the north of Italy to the South, allowing a quick reach from Santa Giulia to Bologna in 45 minutes.

The intervention area, which includes both the former Redaelli and the former Montedison industrial group, covers about 120 hectares and is southeast of the municipal area. The new district extends to the Viale Ungheria settlements to the north, and to the old Rogoredo district to the south, bordering the railway to the west and the ring road to the east.

By rail, the new district is served by the Rogoredo F.S. connected with the Bologna-Milan section on a national scale. In conjunction with the Rogoredo station, there is a metro stop of Line 3, another very important connection at the urban level, as well as a redevelopment element of the area. As we can see, only the south-west area of Santa Giulia is served by the two infrastructural axes, while the north area, that of Montecity, relies only on local tram mobility.

Santa Giulia district is located in an area with high infrastructural development; however, accessibility is not guaranteed at optimal levels for the whole neighborhood. As the southern part of the district is highly connected with railways, metro lines, and urban and local highways such as Via Emilia and A51, the eastern part is connected with the adjacent East Ring Road through 3 junctions along with the Bologna route, the northern part remains quite poor in connectivity as it can be only reached by local transportation such as trams as busses. Such urban planning will have an impact on the distribution of sectors and zoning areas whilst ensuring an extension of tram and bus lines through the neighborhood to provide better and faster connectivity between the northern and southern part of Santa Giulia.

ROGOREDO FS VIALE UNGHERIA AUTOSTRADA 51

CONSTRUCTED AREA OF SANTA GIULIA

AREA FOR CONSTRUCTION