HISTORY | TYPES OF ICE-RINKS

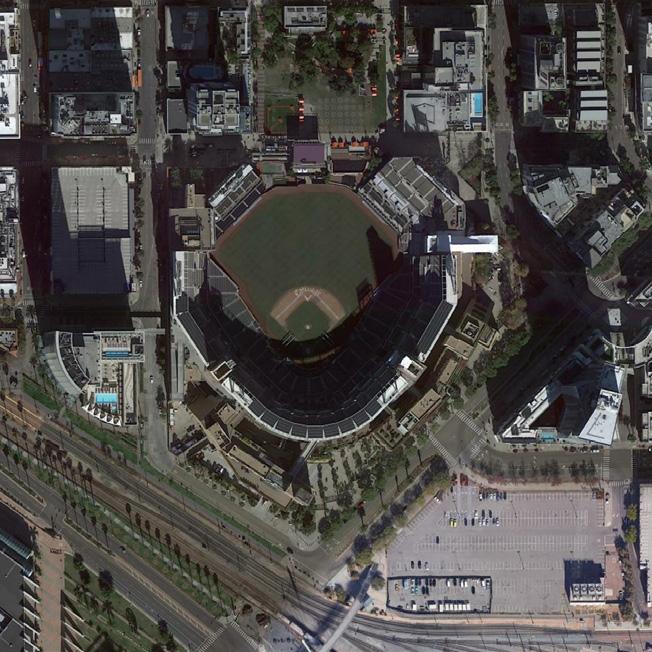

FORMS AND REPRESENTATIONS

A natural ice rink can be found on open bodies of water such as lakes, ponds, canals, and sometimes rivers. If a cold climate allows it, it would be possible to achieve such a rink in which it has to be thick enough to withstand the human loads. Rideau Canal Skate Way in Ottawa, Canada, is a remarkable example of a natural ice rink, with an estimated area of 165,600 m2 and a length of 7.8 km, which is comparable to 90 Olympicsize skating rinks. The rink is available 24 hours a day and is prepared by decreasing the canal’s water level and allowing the canal water to freeze. The season’s duration is determined by the weather, although the Rideau Canal Skate way usually opens in January and closes in March.

However, our interest in such thesis lays on indoor ice-hockey rinks, meaning ice hockey arenas and how they were developed at first, and modern days arenas.

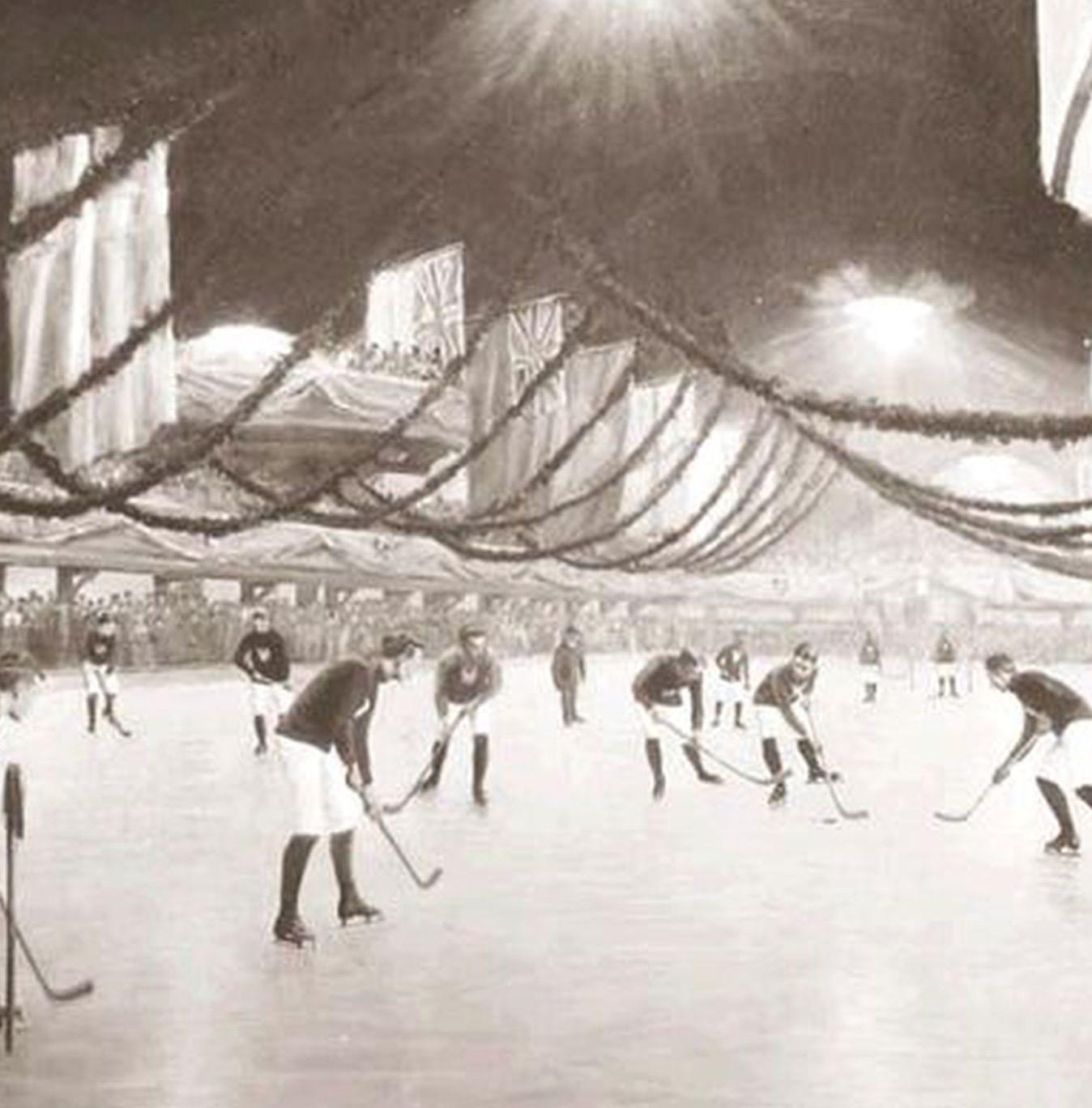

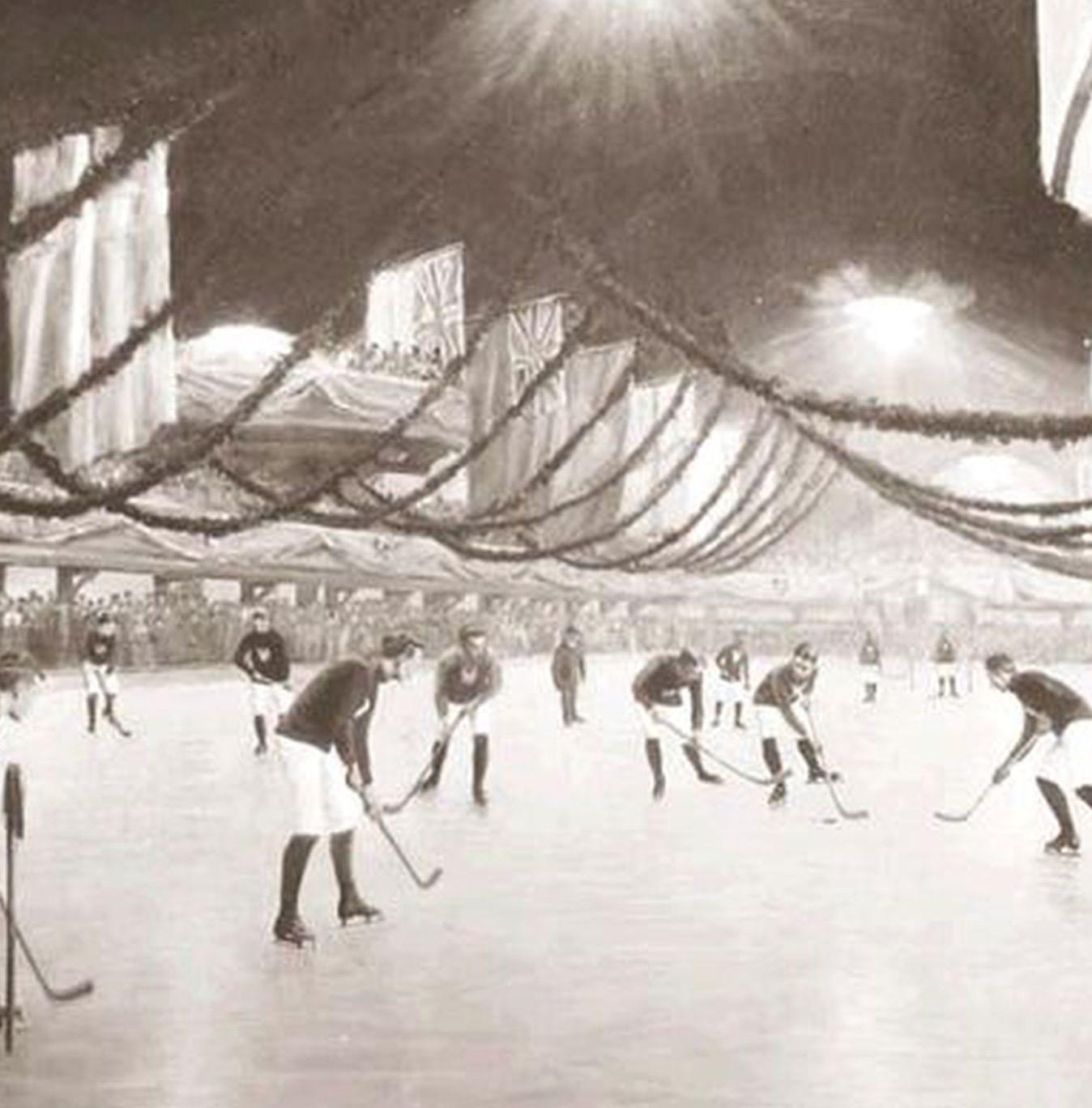

Following Gamgee’s method in which he designed Glaciarium, the first world’s mechanically frozen ice-rink, designed on June 8,1844, different ice rinks were designed in tents. Due to its expensive costs of manufacturing and maintaining and due to the mists rising from the ice which deterred the customers, those rinks and tents were shutdown. Southport Glaciarium, on the other hand, opened in 1879 utilizing Gamgee’s technique.

MATHEWS ARENA

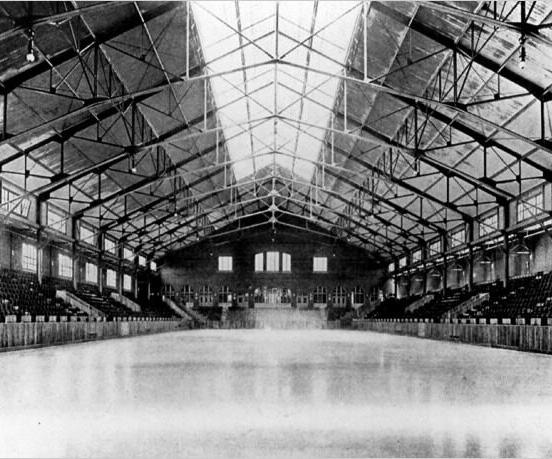

One of the oldest stadiums hockey arenas in the world that is still in use, as well as the oldest multi-purpose athletic building that is still in use, is Mathews Arena in Boston. It opened in 1910 and it suffered several damages, it was burnt in 1918 and another time in 1948. Such fires caused severe damages to the facades as well as the roof. However, we can clearly see through the photos that the original design, which is still quite similar till today, was in rectangular shape with a sloped roof, a typical warehouse design and not reflecting the internal activity. the design was simple and pure in its geometry, unlike stadiums in 1920s where they became to be athletic in their style. The glass panels found on the facades as well in the sloped roof were for daylight and light transmission for the games or even dance shows. The glass panels on the roof are still preserved till today; however, the ones on the façade were eliminated and substituted with more artificial interior lighting.

MADISON SQUARE GARDEN

Another formal and rectilinear geometric stadium with a similar roof approach is the Madison Square Garden in New York city. It was the third MSG which opened in 1925 and closed in 1968. Due to its shape, it was a multipurpose arena, capable of hosting different events from hocket, boxing, basketball, and many others. The design was a simple box in which the structural skeleton is visible in the façade. The architectural compositions as well as the articulation of volumes were of pure expressions of functionality of the building. The slope found in the roof was for the necessity of the interior space for higher heights, as it accommodates thousands of spectators and thus for rational purposes, the roof was designed not in unity with the geometrical shape of the building. Moreover, the inclined roof with glass panels in between allowed for the penetration of light needed for the interior activity.

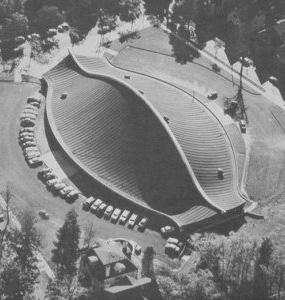

DAVID S INGALLS SKATING RINK

Different forms and shapes for ice rinks started to appear and one of the classical and famous stadiums for ice hockey, representing lightness and simplicity is David S Ingalls Skating Rink by Architect Eero Saarinen. Such stadium was characterized by its curvilinear shaped roof, similar to a whale. It was built in 1958 in the United States as well. The innovative structural composition of the roof was composed of a 90 meter reinforced concrete arch with cable net is strung from. Covering such structure, timber woods were used a finishing material, adding luxury and charm for the design in which it can be seen and reflected from the exterior and the interior as well. This results in a stable double-curvature shape. During the structural design process, external wires connecting the arch to the roof’s outer borders were installed.

Such a stadium, erected 30 years later, may clearly exhibit the progression of forms and materials, with the unpainted concrete of the main building contrasting well with the color and texture of the oak roof. The main entrance’s glass curtain wall adds a stunning contrast to the materials.

Although the rink is in rectangular form and tilted edges, the arena’s roof took the project to new heights, setting new landmarks and design ideas for future stadiums. The arch-shaped roof demonstrated how high heights can be achieved while adding architectural insights to the projects. It sets it apart from the previous projects discussed and leads the way for various design shapes.

LEFRAK CENTER AT LAKESIDE / TOD WILLIAMS BILLIE TSIEN ARCHITECTS

In the previous examples, we demonstrated how enclosed ice rinks have started and how the arenas have evolved into different shapes.

LeFrak Center in Brooklyn, United states was built in year 2013 by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects. The design features a detached canopy of 33m by 70m supported by irregular columns, in which an ice rink is sitting underneath. The canopy’s lowest layer is midnight blue, with a silver design inspired by figure skating footwork patterns etched onto it. In the off-season, the rink operates as a roller rink and event venue, bringing roller skating back to Brooklyn for the first time since 2007. In the summer, the ice rink, underneath it, is extended to the exterior, producing an elliptical rink that transforms into a water feature, providing a play environment for children and families. The canopy’s roof is accessible, allowing for a terrace view from the upper layer, overlooking the park and the frozen elliptical geometry where kids and adults are playing.

Such project is a clear definition and transformation of typical ice rink arenas into a more playful and park arenas, specially that ice rinks were originated at first from nature, frozen lakes. The LeFrak Center at Lakeside is a public venue that provides a location for enjoyment, where skill and poetry collide.

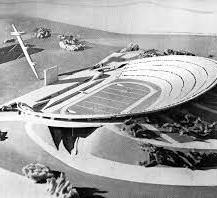

SKI CENTER, STADIUMS, URUMQI, CHINA

In the latest decades, an ice rink stadium became a part of a complex center for winter games, in which several arenas are build one next to another in order to host either a winter Olympic competition or a national one. In general, these buildings feature new technologies and organic and dynamic shapes in their designs.

Ski Center in China is a complex of stadiums designed to host China’s 13th National Winter Games. It is a center of several stadiums, built in 2014 and designed by Architectural Design and Research Institute of Harbin Institute of Technology. The master plan is a layout which provides the citizens and athletes with diverse activity spaces. It is based on the rational arrangement of events as well as the molding of the environment during and after the activities.

The design was highly influenced by its surroundings as it was inspired from the snow-capped mountains and Gobi unique to Xinjiang The white roof reflects the shape of a natural cap with horizontal lines that have been layered processed to imitate the distinctive rock formations of the Gobi Desert. Such effects give the impression of the whole complex as if it is being tucked in the snow white, with an elegant and resourceful façade in good harmony with the environment.

The reason we decided to cite such example in our thesis is due to its shape and design inspiration, as it clearly demonstrates the evolution in way of thinking and imagining stadiums, from a simple rectilinear box with sloped roof to a more dynamic shape reflecting its white surrounding. As modern arenas were becoming more safe, comfortable, and more accessible, they were able to attract a wider collection of spectators and most importantly a diversified one.

The arenas weren’t only upgraded in the sense to respect the new standards regarding safety; however, such process allowed for a greater opportunity to introduce business activities inside, merchandising, museums, guided tours, and restaurants which became popular and spread over several floors. With the help of these facilities, alongside recreational and leisure areas, arenas are being managed differently and treated as a public area not only used for sports events. Stadiums are now an important figure of the city, hosting several functions in which the community is in need for it, thus allowing it to open seven days a week and not only on game days.

This new approach allows the stadiums to be the center of the evolutionary process of contemporary cities, as key elements in development and new centers of attraction. However, in recent years stadiums have gone out of control as expenses and costs have reached unimaginable numbers which requires strict planning in terms of economic and environmental sustainability, without jeopardizing their sports nature and architectural qualities.

We highlighted through history and cases presented, how stadiums and arenas have changed throughout time and how for every generation has its own design and technological and structural innovations. For the next generations to come, architects and designers are racing for avant-garde designs which it is an exciting architectural challenge pushing the limits for a new step in the evolutionary process of stadiums.

SYNTHESIS BETWEEN FORM, FUNCTION, AND STRUCTURAL TECHNIQUES

SYNTHESIS BETWEEN FORM, FUNCTION, AND STRUCTURAL TECHNIQUES

FORMS AND REPRESENTATIONS

After the whole demonstration of different stadium typologies and different structural techniques used to construct the shape of the envelope, whether it was an enclosed stadium, or the shape of the floating or partial roofs, we were able to synthesize from that analysis and study, two shapes for stadiums: The enclosed stadium (envelope) or Stadiums with detached roofs.

The choice for shape and type of roof, alongside the use of glass in the facades or skylights, rely solely on the facility hosted and designed for. Thus, the architecture and composition of the stadium must demonstrate and respect the preferred environment for the sport event occurring under such structure. They are a feature of synthesis and conclusion between form, function, and construction; while respecting the environmental sustainability needed and the economical sustainability as well.

Architecture of sports must be a unitary system capable of guaranteeing aesthetic, quality, comfort, and flexibility. It is a controlled shape of certain dimensions, respecting the playing field its hosting, with directed orientation with relation to the urban context.

SOCIAL FUNCTION AND SYMBOL OF THE CITY

SOCIAL FUNCTION AND SYMBOL OF THE CITY

VALUE AND POINT MARK OF CITIES

We have mentioned in the beginning the role of sport buildings in society and the symbolic values they play in the city. In our modern days, the symbol of the city has clearly become the sport buildings, as they are the center of attention and huge financial and technological investments are occurring in such architecture. Just like architecture in previous centuries was highly visible in castles and palaces, these days, such efforts, technical innovations, and designs are occurring in sport buildings. Stadiums, designed initially for sports, are once again an essential component of the city, being an urban frame of public spaces and services, providing different sport activities while hosting as well cultural and leisure facilities. These scenarios are marking the return of stadiums, their significance effect on urban cities, in design and architecture, in structure and technologies, and finally on society and the surrounding community itself.

Sport buildings are pioneer in architecture and design, they’re a mixture of strong innovations and complexity, simplicity and detailing, structures and technology. They are as well a center hub for thousands of people where they can gather and meet, for sporting events, for concerts, for campaigns, or other events taking place. For this reason, sport buildings are a unique phenomenon in urban life. Their construction strongly influences the city life, the urban planning of the masterplan and the city. It is an extension of city’s streets and street life, a gathering point for sports and commercial purposes.

Various cities are known nowadays due to the stadiums built there, as they provide a strong framework for the representation of the city.

As mentioned, sport buildings have an impact for urban planning, for the city grids, for the construction of streets and highways, but in addition, it forces the construction of rail works and extensions of highways; thus, having an imminent impact on infrastructure.

Not only that can be found on infrastructure, but sport buildings also play a major role in the economic development of the host city, through the multiple investment which take place, as well as, the commercial center which are often found in the stadium or force their construction next to it.

Various factors lead the arenas to be a symbol of the city, from their architecture design to their effect on society, urban planning, economic growth. Stadiums are an essential parts nowadays for a rising community and their symbolic value is often felt and perceived in several scenarios and sectors.

RELATION WITH CITY AND LANDSCAPE

SPORT HALL RELATIONS WITH CITY AND LANDSCAPE: PRINCIPLES

We can understand urban relations among sports halls and cities mainly debating 2 categories of principles: Integration and Place. Integration relates to sports hall facility can harmoniously communicate with the city while place relates the sports facility with a local symbolic dimension.

Integration

Integration can be understood starting from 3 key principles: Context, Connectivity, and Accessibility.

1) Context

When talking about the context, we can understand it in terms of its location about the city and its Integration with surroundings.

1.1) Locations

There are 3 basic typologies: the urban, the suburban, and the periurban.

1.1.1) Urban

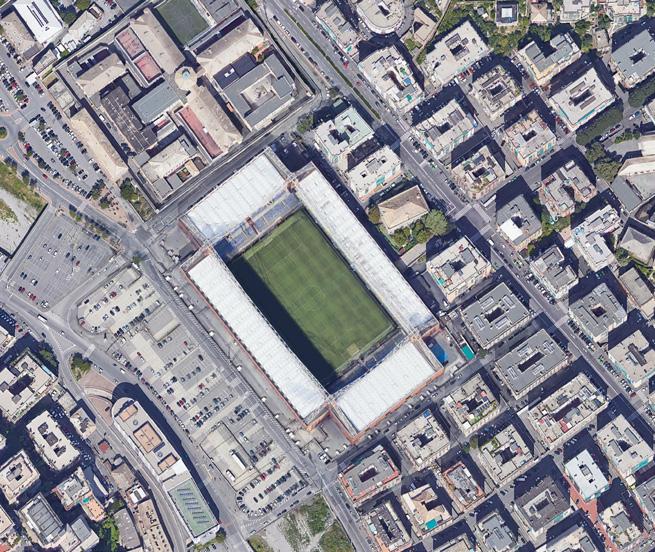

Urban sports facilities are normally deeply embedded in the urban fabric and are normally constrained to the dimensions and modularity of urban blocks. Good examples of such sports facilities are the early football stadiums built by A. Leitch in Glasgow and Liverpool. Both were

built in a residential context following the logic of the neighborhoods in the surroundings, according to their urban axis and directions. Urban contexts offer countless opportunities for the city, becoming a landmark and offering legibility to the territory. The Sport Hall enclosures can offer an active frontage and vibrant streets, establishing a frank dialogue with the city also on non-match days. Real estate prices and regulations make this kind of typology rare, though. Most of the time, we can only find such structure when a renovation of an existing Sports Hall is taken into consideration.

vibrant streets, establishing a frank dialogue with the city also on nonmatch days. Real estate prices and regulations make this kind of typology rare, though. Most of the time, we can only find such structure when a renovation of an existing Sports Hall is taken into consideration.

1.1.2) Sub-Urban

Sub-urban settings can be a problem considering the low attractivity that they may have. When not adequately treated, it may become uneconomical for public transport connections and active frontage. This can generate as an imperative the use of the car and generate desert and extensive parking lots, and, consequently, no natural surveillance. It can be adequately treated, though, when connected with a bigger urbanistic and landscape plan, that can insert the sports hall in a park context, not merely as a sports facility, but also as a meaningful new public assembly. A good example of such configuration was proposed by Le Corbusier in the Stadium for 100.000 places, in Paris.

In this project, the Stadium was thought of as a new formal public assembly, in the landscape of the park. The shell is placed in the greenery, with a big canopy roof that provides shadow to the supporter studying the movement of the sun.

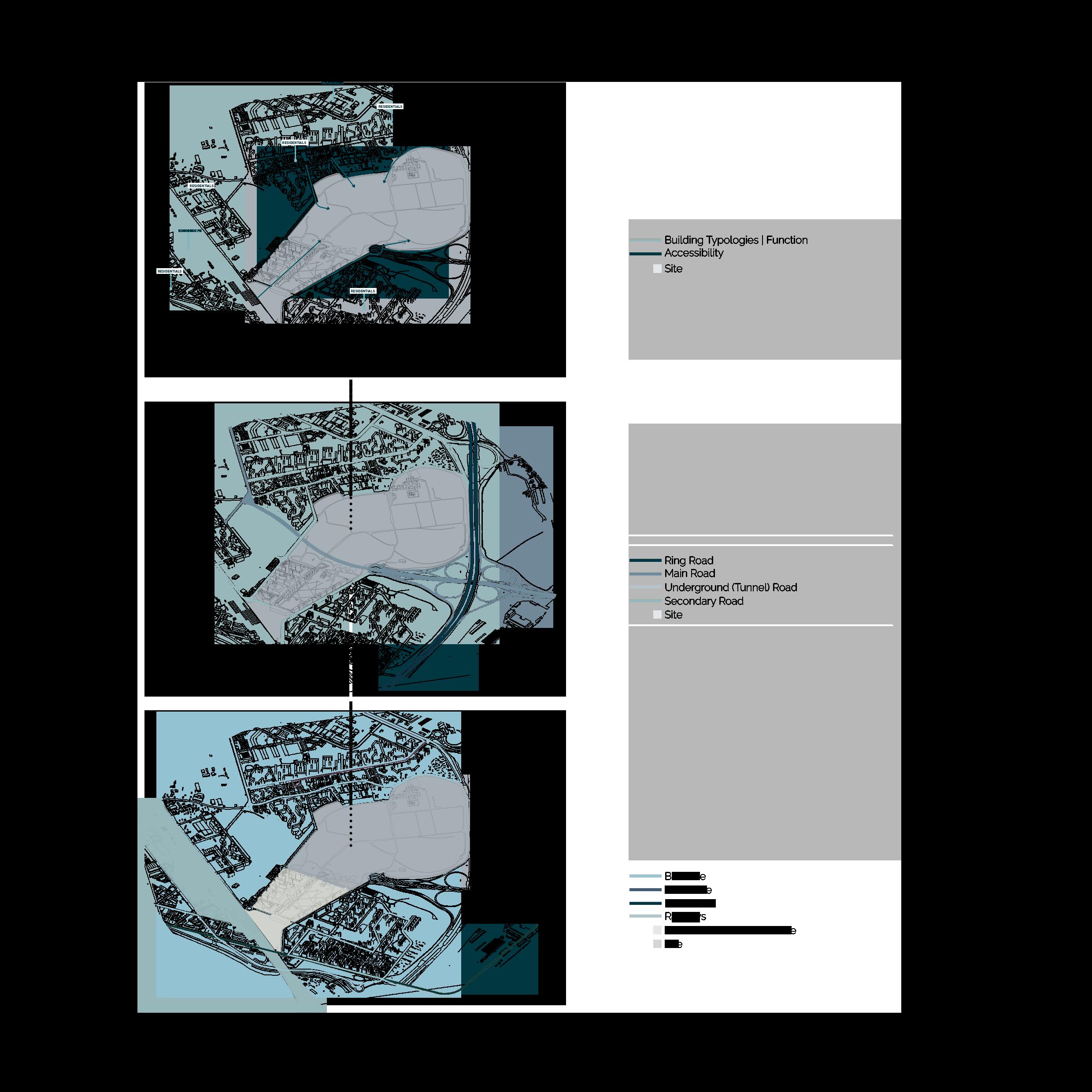

The Sub-Urban context is what we find in Santa Giulia, after the reconfiguration of the area from an industrial settlement to a new green area in the context of the new PGT (Piano di Governo del Territorio) for Milan. Being an expected park, surrounded by a residential area under

redevelopment, it offers to the Sports Hall designer the opportunity of, at the same time, has the advantage of building a new public facility enhanced by the landscape, but also a population density that justifies its use on non-game days.

1.1.3) Peri-Urban

These Sports facilities are typically built for major events, like World Cups or Olympics. Their use after the events are likely to be below the design. This makes these structures have no function at all and have a huge financial and environmental cost. We can exemplify it with the Jeju Stadium, built for the Japan and South Korea 2002 World Cup, which is situated in the rural countryside of Jeju Island, in South Korea. The decentralization from city to suburbia is evident across the globe. But these peri-urban locations are often split apart emotionally, physically, and visually from the city, which contributes negatively to the sense of belonging for supporters.

1.2) Integration with surroundings.

Regardless of the context (Urban, Suburban, or Peri-urban site), the sports hall should integrate with its surrounding context. There is a responsibility of considering the existing setting, connections, block scale, urban morphology, and vertical scale, to be sure that the sports facility will enhance the environment in that location and provide the best benefit that integration may provide.

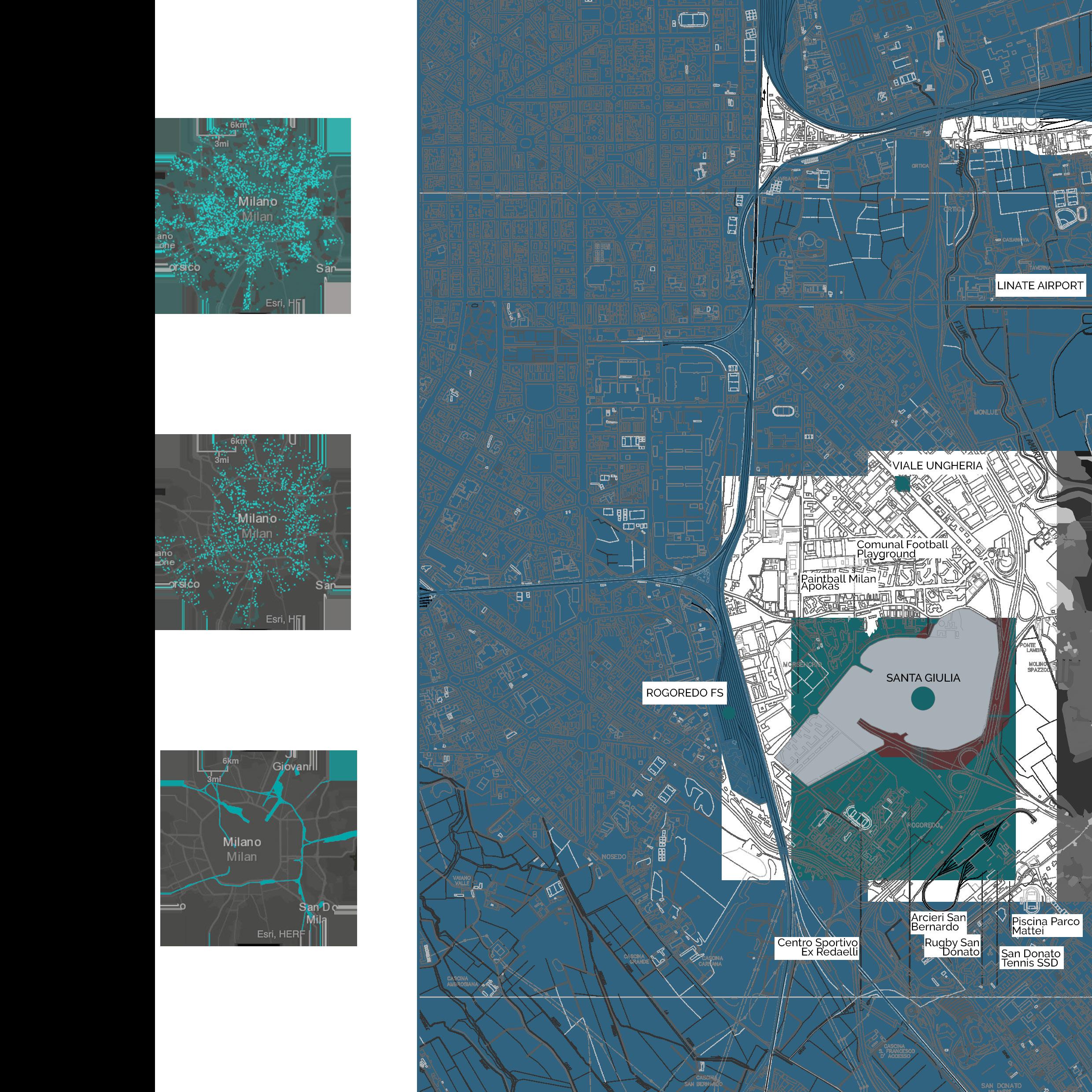

As already anticipated, Santa Giulia lies on a sub-urban field, presenting low density. However, it presents high accessibility, with the train, metro, and highways infrastructures nearby, which allows us to transform it into a place for use also on non-event days. This opportunity will be further explored with the design of the park and the internal functional gallery inside the Arena.

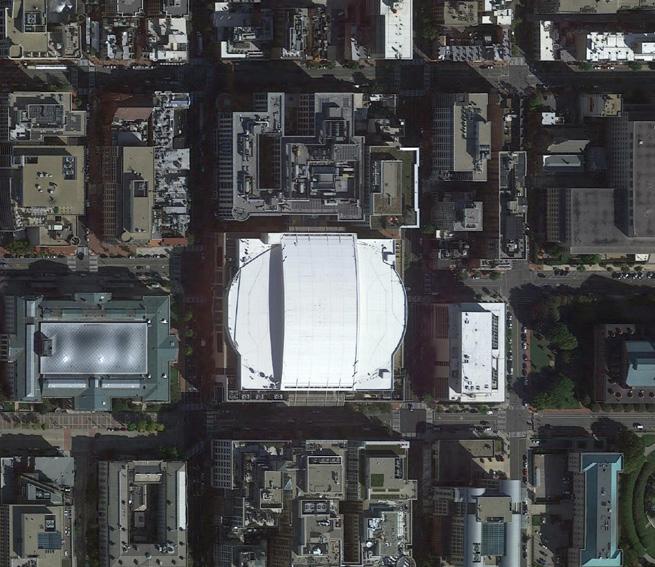

Arenas should also follow the urban movement and morphological patterns. The pictures aside show good examples of how the

morphology can be respected despite the relatively big size of arenas. The size, orientation, and shape of new arenas should ensure that existing movements and patterns are kept, enhanced, or created.

It is easier to identify these morphology patterns in an urban context, but it is also possible, extrapolating a larger context and the meaning of Santa Giulia as a strategic green area for Milan, to understand the pattern of the open blocks in the southeast part of Milan to repropose a neighborhood in Santa Giulia and insert the Ice Hockey Arena as an enhancer of the landscape design aligned with an urban pattern characterized by the existence of green open spaces.

2) Connectivity and accessibility

The success of a new Arena must have high levels of connectivity and accessibility. That can only be achieved with a public transportation infrastructure that allows a location to be reached by a significant amount of people in a reasonable time and price. When arenas are too detached from the urban perimeter and need to be reached by cars, that creates an issue of creating large areas for parking lots. Parking lots, besides being a huge waste of land, is also a barrier to pedestrian, and, by extension, to full integration between Arena and city.

The integration comparison picure exemplifies how isolated Arenas can be when they do not provide easy and clear access from public transportation for spectators.

The immediate surroundings for a stadium, then, should be a pedestrian space. The experience of going to the Arena should be though since the moment a fan enters a public transportation station, passing through when he/she gets off in the closest station and walks to the Arena. The connection between the station and the Arena is a priority. This clear principle was followed in the decision on where to place the Arena in Santa Giulia. The access should be the more enjoyable and direct as possible. That is why the Arena was placed aligned with the boulevard (designed in Foster’s plan) and comes from Rogoredo Station. Taking

advantage of the already existent boulevard, it is possible to provide a pleasant experience to the spectator, through a controlled microclimate and the availability of convenience and safety.

Place

The principles that govern the understanding of place in the relation of sports hall and city can be classified as Sense of place, Destinations, and Local Identity.

1) Sense of place

Because of their dimension and importance, arenas should be considered as civic buildings. As so, the place around Arenas should have a public realm. This public realm can add an image and identity to the place itself. As people meet and get together around arenas, they will probably spend more time outside their stands. That is why is crucial to provide complementary uses and activities as well as active frontages, to enhance the public sense.

In the Design of Santa Giulia’s Arena, the public realm was enhanced by the design of a park, connected with the existing built environment, a boulevard, and an interior gallery, which provides additional uses for the spectators and the public in general, when in non-event days. The built environment and natural characteristics can make the spectator experience and the city’s image better. The Arena can offer views of key features, as a skyline, a coast, or a park. This helps to bring unique character to the Arena and create a bond between Arena and its community. Souto de Moura’s Braga Stadium is a good example of how an Arena can enhance the view of a particular landscape. There are many situations in which an Arena can enhance the supporter experience in different contexts, exemplified in the comparison of contexts.

Santa Giulia characteristics, thus, will imply a park setting context surrounded by a residential suburban one.

A case study for the concept definition for Santa Giulia’s Arena was SAP Arena, designed in Munich by 3XN architects (figure aside)

The stand-alone appearance of SAP Garden Arena also inspired the box-shaped design of our enclosures, in such a way that the integration of the landscape with the building would happen through different height connections to the landscape, enhancing, at the same time, the appearance of the form itself and the design of the landscape.

2) Destinations

Arenas should be a destination to attract people not only on event days. The goal, then, is to insert the Arena in a wider mixed-use destination. This makes people flows more viable and increases attendance, increasing the expenses of people visiting the area and having a positive economic effect on the neighborhood.

Our design in Santa Giulia was, then, worried in providing this by creating a gallery (inspired in the Milanese tradition) to bring different uses for the Arena and make it an everyday place for the community in the surroundings, but also those visiting the park around. This commercial use for the area will also be enhanced by reinforcing the existent commercial boulevard built by Norman Foster’s proposal (2004).

2) Identity

The arena surrounds and public realm should enhance the local identity. This has to be done by taking reference from local and vernacular culture and reinterpreting it in contemporary content. This was achieved in Santa Giulia’s Arena design after a deep understanding of Milanese civic and public spaces design. Analyzing references as Rotonda Della Besana, Lazzaretto, and Galleria

Vittorio Emanuelle, it was possible to conclude that the typical Milanese public space is a central construction, surrounded by rings by a void and again a construction. This, extrapolated, inspired the design of Santa Giulia Arena creating a gallery that gives access both to the main building (the Sports Hall) and the functions exterior ring.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS AND STRATEGY

SITE ANALYSIS

SITE ANALYSIS

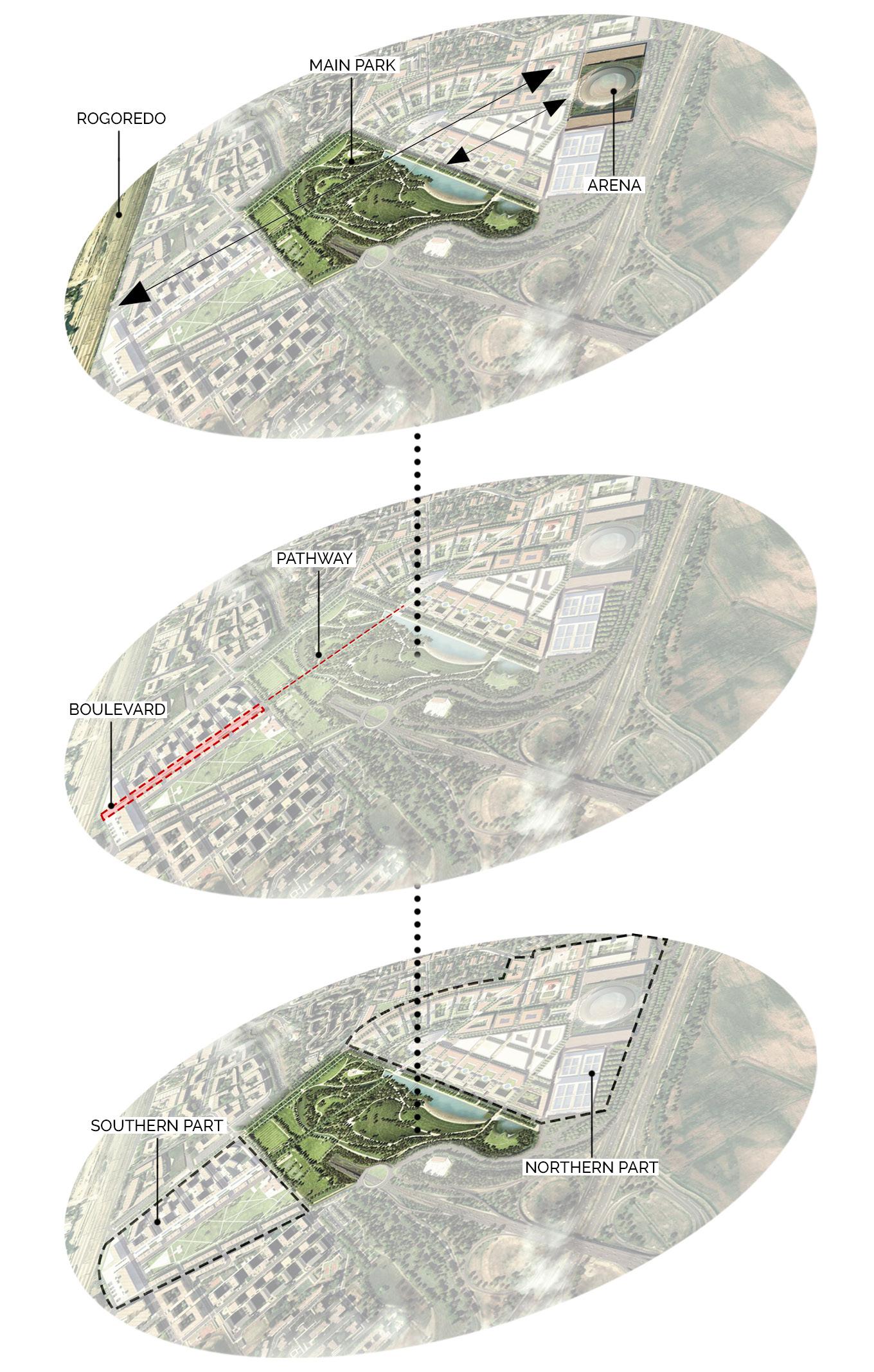

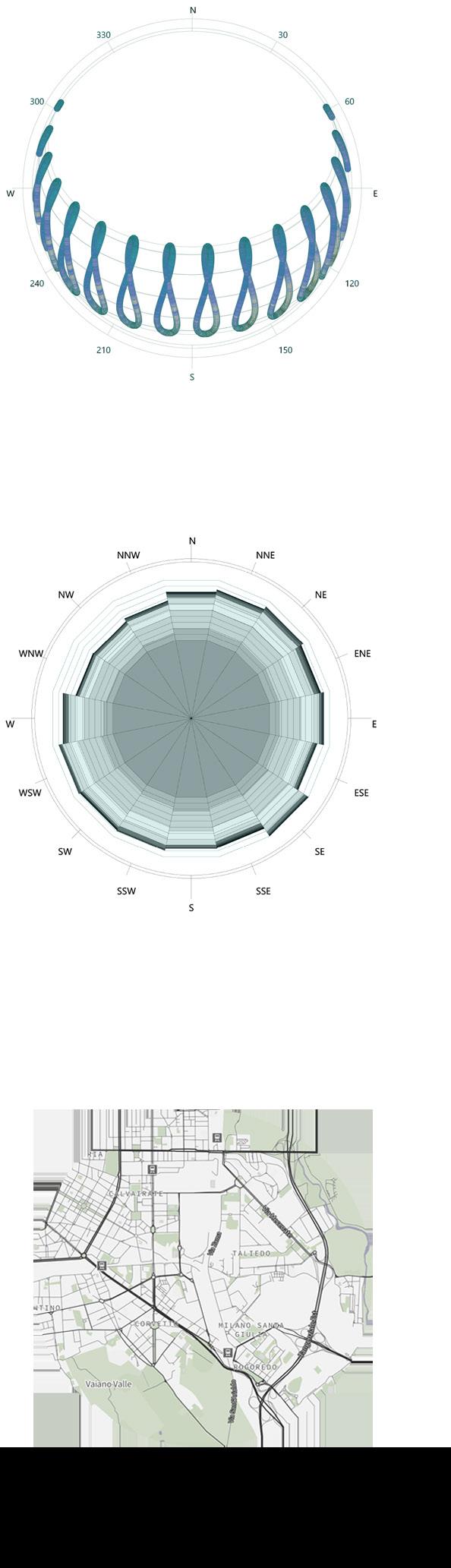

ANALYSIS AND STRATEGY

In our previous analysis and studies, we focused on the context of Santa Giulia and its origin; however, in such study, we focus directly on our site on a smaller scale. Our site is located on SouthEast periphery of Milan, in the Zone 4 administrative division, and its area reaches up to 296 acres (1.2 km2). The site’s location can withstand and welcome different age groups, as through the division and spread of population around in Milan, the senior and the young population is equally visible in that area. Such analysis proves the capability of making a masterplan consisting of an arena, sport parks, commercial street and business buildings, which allow different age groups to benefit from the project during time zones of the day. The site clearly benefits from various infrastructures regarding transportation which facilitates and ease the transfer of players and VIPs in private vehicles, and spectators in public transportations though railways and private vehicles as well. It is bordered on the south from Rogoredo train station, which leads to Bologna and south of Milano. Such station is also a junction point of Metro Line 3, considered a strategic metro line in Milan, which connects Duomo station, Centrale station, Porta Romana station, Rogoredo station, and finally San Donato station. And finally, the site is only 7 minutes away from Milan’s domestic airport, Linate, through the adjacent highway found of the right of the land. On the other side of side, it is considered to be weaker in terms of local and urban transportation; however, it still occupies several tram and bus stops which circulates around.

As we look around the highlighted area for construction, we realize the presence of several sport facilities, consisting of Rugby fields, swimming pools, tennis courts, and communal football ground. These facilities allow Santa Giulia to be the perfect location to host the Winter Olympics 2026 Ice Hockey Arena, as it complements the whole area and adds a significant value for sports in that location.

The site is located on the south-east of Milan, with a Paullese Street passing right under it through a tunnel, which acts as an entry gate for Milan. The specified area, known for being an industrial zone, is now consisting mainly of residential buildings, with certain exceptions where we can still see the industrial buildings. It is considered to be an under-developed zone with not much real estate and big projects being constructed, and for that matter, Santa Giulia district is designed to alter this perception.

The site’s accessibility is defined by present entry points, like the boulevard which connects Santa Giulia to Rogoredo and crosses between the constructed residential buildings. Such boulevard is of great importance in our analysis which will later lead to the development of the masterplan. Other accesses can be from the ring road on the side, and several streets branching out from Viale Ungheria on the north part.

RECENT PROJECT’S PROPOSAL | STUDY AND CRITICS

RECENT PROJECT’S PROPOSAL

STUDY AND CRITICS

Foster & Partners were asked to design a sustainable and smart district of Milano Santa Giulia, in which the masterplan consists of different facilities from museum, residential buildings, sports arena, commercial buildings, businesses and offices, and leisure facilities.

Following such masterplan, we highly analyzed the proposed urban planning, and we were able to highlight different factors and elements which we believe must be revised. Such critics and considerations will later help us to design a different masterplan, consisting of same facilities; however, with better linkage and architectural considerations.

The intervention favors relations with the rest of the city and the metropolitan area. The extension of the Paullese road increases the connection towards the city center and connects the district with the eastern ring road. However, the initial idea was to join the two parts of Santa Giulia, rather than keeping them split as they were in origin. However, the large green public area, Santa Giulia Park, is located right in the center of the plan, favoring a greater division of the areas of Montecity to the north and Rogoredo to the south to the detriment of the unity that the plan envisaged. The proposed park does not function as a connecting landscape within different facilities and buildings, yet it is a large green area with no facilities to interact with.

What the plan does not consider as well is the evolution in Milan’s morphology of buildings and districts. The farther we get from the center, the more openness, and light buildings we observe. Such strategy was not applied in the masterplan, as it was compact, and the buildings are designed to be closed-up with bringing back the original courtyard concept between different parcels blocks. Such scenario does not favor the vision which Milan is trying to achieve, an open community allowing more spaces for greenery within buildings and dynamic spread of structures with organic pathways. What has been proposed acts as an exclusive neighborhood with a discontinuity from the surroundings.

Another important element that we should highlight on is the negligence of the importance of the boulevard which extends from Rogoredo FS and crosses all the constructed part of Santa Giulia. In the current scenario, the boulevard was not extended in the same width nor given the same importance as an axis of accessibility; it would lead to nowhere until it crosses the whole park to reach a certain function.

And finally, the sports arena, which is our main concern, is designed at the very edge of the district with no linking with the park nor with an important railway infrastructure, Rogoredo FS. The arena is placed at the borders of the master plan, facing the street, without a main plaza where fans can gather, nor with a green area acting as sports park. It was left as a secondary element of treatment, rather than the main element in which the masterplan is designed around, as we have seen in the previous analysis. Its location is badly connected with public transportation and totally disconnected and segregated from the park; meanwhile, it has a strong linking connection with the surrounding shops and commercial buildings rather than with the community itself.

Total disconnection and absence of relation between the arena and the park is obvious in such masterplan. Moreover, the arena is located far away from Rogoredo and not benefiting from such an important railway infrastructure.

Abandon of the existing main boulevard of Santa Giulia, in which its width decreases progressively as it starts from the park. This shows the discontinuity between the southern constructed part and the northern part in its main elements.

The main park acts as a seperation element rather than a unification which binds and connects all of Santa Giulia districts. It is design and left as a large green area with no facilities to interact with.