Italian Art

NEW RESEARCH ON ART AND ITS HISTORY JANUARY 2023

Bronzino: a new portrait and other discoveries | Sicilian silver in Malta | Raphael’s anniversary in retrospect Pisanello in Mantua | The Tudors in Manhattan | Recent books on Artemisia Gentileschi | Noguchi in Bern

29 JAN — 5 FEB 2023

EXPO

HEYSEL www.brafa.art

OF THE MOST INSPIRING

WORLD

BRUSSELS

I

ONE

FAIRS IN THE

GIUSEPPE MOLTENI 1800–1867 Portrait of Marchese Antonio Visconti Aimi (1798–1854) c. 1830–35 www.robilantvoena.com

29th January – 5th February 2023

Brussels Expo, 1020 Brussels

For more details visit: brafa.art

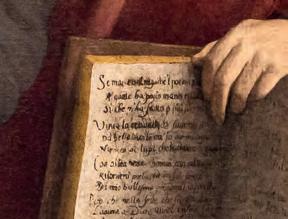

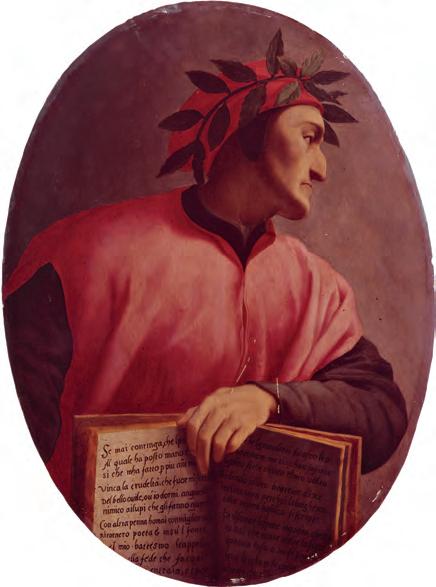

IT IS REASSURING to both public and private collectors and the wider commercial art world that BRAFA, a museum quality event, is returning to its New Year position in the fair calendar. After the success of 2022, the 68th edition will again occupy two capacious halls at Brussels Expo. With 130 exhibitors from all over the world, this truly international event will showcase a diverse range of objects dating from prehistory to modern times. This year BRAFA has chosen Art Nouveau as its thematic focus. The 2023 iteration of the fair will celebrate the art movement with a talks programme, special events and selected dealer displays; even the design of the fair will pay homage to this heritage.

Large-leaf verdure depicting a stag and doe. Southern Netherlands, 1550–1600. Wool and silk, 270 by 178 cm.

DE WIT TAPESTRIES, MECHELEN

Lega figure. Democratic Republic of Congo, early 20th century. Wood and pigments, height 29 cm. DIDIER CLAES, BRUSSELS

Avarice, by Pieter van der Heyden (c.1530–72) after Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c.1525–69). Engraving, 29.6 by 22.5 cm. BELGIAN ANTIQUARIAN BOOKSELLERS ASSOCIATION (BBA), BRUSSELS

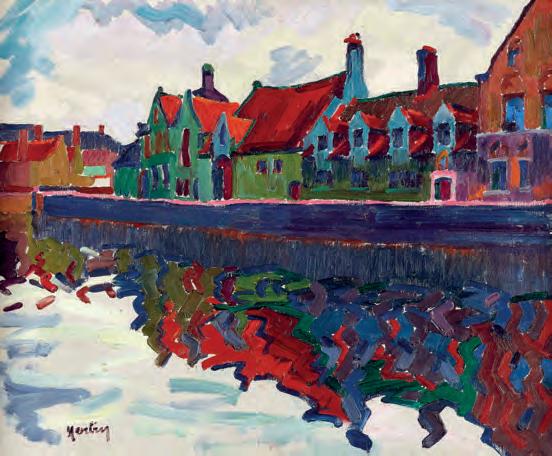

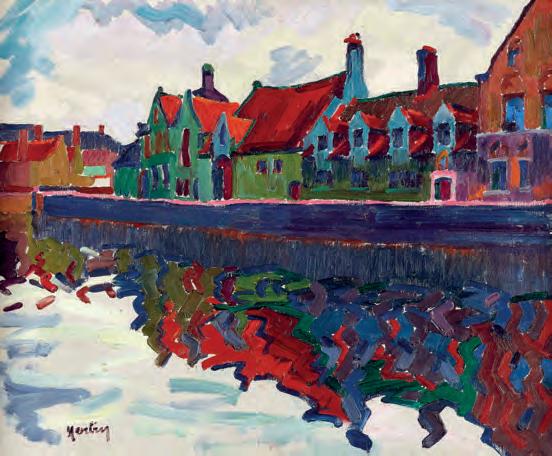

Maisons au Quai Vert, Bruges, by Auguste Herbin (1882–1960). 1906. Oil on canvas, 53 by 64 cm. STERN PISSARRO GALLERY, LONDON

The temptation of St Anthony, by Pieter Huys (1519–84). Oil on panel, 41.8 by 57.8 cm. DE JONCKHEERE, GENEVA AND PARIS

The temptation of St Anthony, by Pieter Huys (1519–84). Oil on panel, 41.8 by 57.8 cm. DE JONCKHEERE, GENEVA AND PARIS

The head of Saint John the Baptist presented to Salome Estimate $25,000,000–35,000,000 SCAN HERE TO LEARN MORE 1334 YORK AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10021 ENQUIRIES +1 212 606 7230 SOTHEBYS.COM/MASTERPAINTINGS #SOTHEBYSMASTERS © SOTHEBY’S, INC. 2022 NEW YORK 26 JANUARY

SIR PETER PAUL RUBENS

29th January – 5th February 2023

Brussels Expo, 1020 Brussels

For more details visit: brafa.art

Golden pheasant China, Quinlong period (1736–95), c.1750–70. Porcelain with polychrome, height 35.5 cm.

GALERIE BERTRAND DE LAVERGNE, PARIS

Crate table, by Gerrit Thomas Rietvelt (1888–1964).

1935. Wood and brass, height 63 cm.

GALERIE VAN DEN BRUINHORST, KAMPEN

Green table, by Henri Hayden (1883–1970).

1917. Oil on canvas, 81 by 54 cm. SIMON STUDER ART SA, GENEVA

Psycho-site, by Jean Dubuffet (1901–85). 1981. Acrylic on paper, 50 by 81 cm. GUY PIETERS GALLERY, KNOKKE-HEIST

Family portrait. Antwerp school, c.1620. Oil on canvas, 134.5 by 159 cm. KLAAS MULLER, BRUSSELS

Family group, by Henry Moore (1898–1986). 1945. Bronze, height 18 cm. OSBORNE SAMUEL

GALLERY, LONDON

Psycho-site, by Jean Dubuffet (1901–85). 1981. Acrylic on paper, 50 by 81 cm. GUY PIETERS GALLERY, KNOKKE-HEIST

Family portrait. Antwerp school, c.1620. Oil on canvas, 134.5 by 159 cm. KLAAS MULLER, BRUSSELS

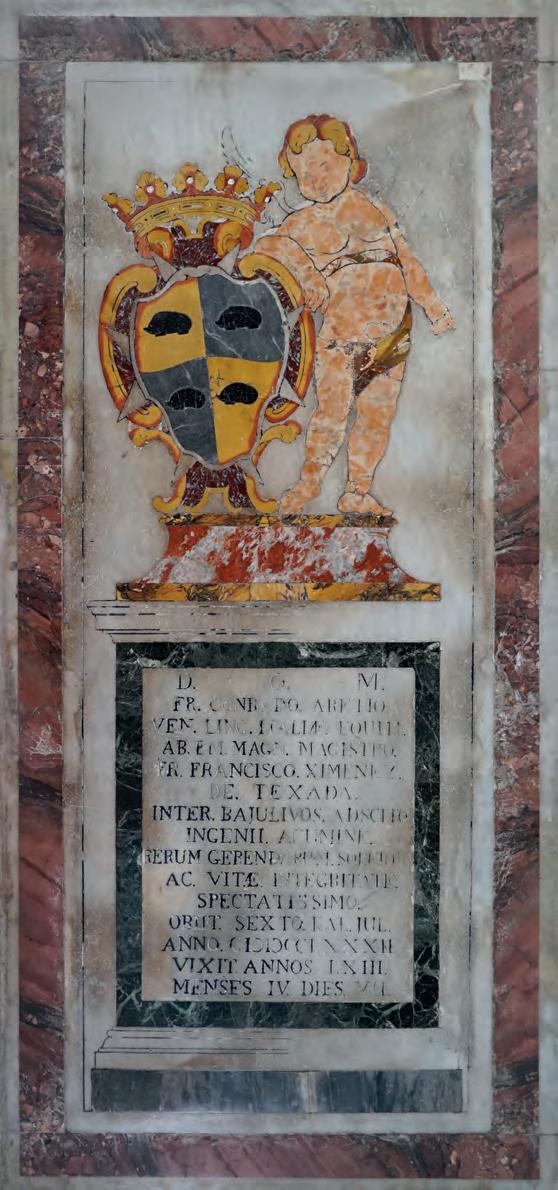

Family group, by Henry Moore (1898–1986). 1945. Bronze, height 18 cm. OSBORNE SAMUEL

GALLERY, LONDON

Rare New Seasons Catalogue

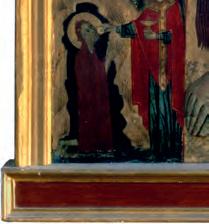

A Very Rare and Important Marble Relief of the Resurrection of Christ Attributed to the Master of the Mascoli Altar Marble, Venice, Italy

Second half of the 15th Century provenance: Former French Private collection, gallery of Gustave Clément-Simon (1833–1909), in his Castle of Bach, Naves (Corrèze, France) since the late 19th century Thence by descent until 2013 Ex Private collection

w: www.finchandco.art m: +44 (0)7768 236921 e: enquiries@finch-and-co.co.uk

number 39 available upon request Exhibiting at: BRAFA Art Fair 29 Jan – 5 Feb 2023 Brussels Expo Heysel, Brussels Belgium

vi the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023 Print and online from less than £15 per month 40% off for new readers and gifted subscriptions shop.burlington.org.uk/promotion/seasonal

SLOANE STREET AUCTIONS Zero seller’s fees at Sloane Street Auctions 69 LOWER SLOANE STREET, LONDON, SW1W 8DA INFO@SLOANESTREETAUCTIONS.COM - +44 (0)2072590304 - WWW.SLOANESTREETAUCTIONS.COM 1st March 2023 - Lot 71 - £20,000-30,000

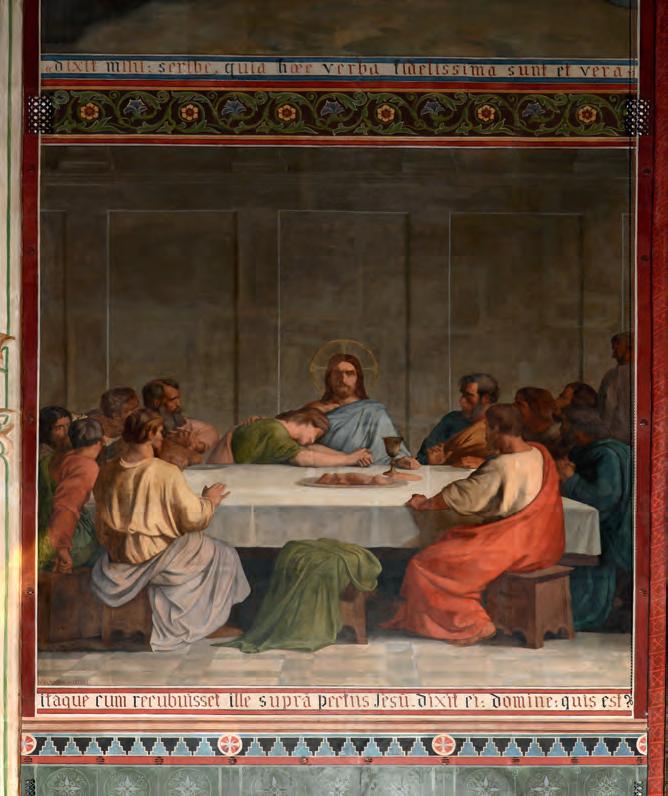

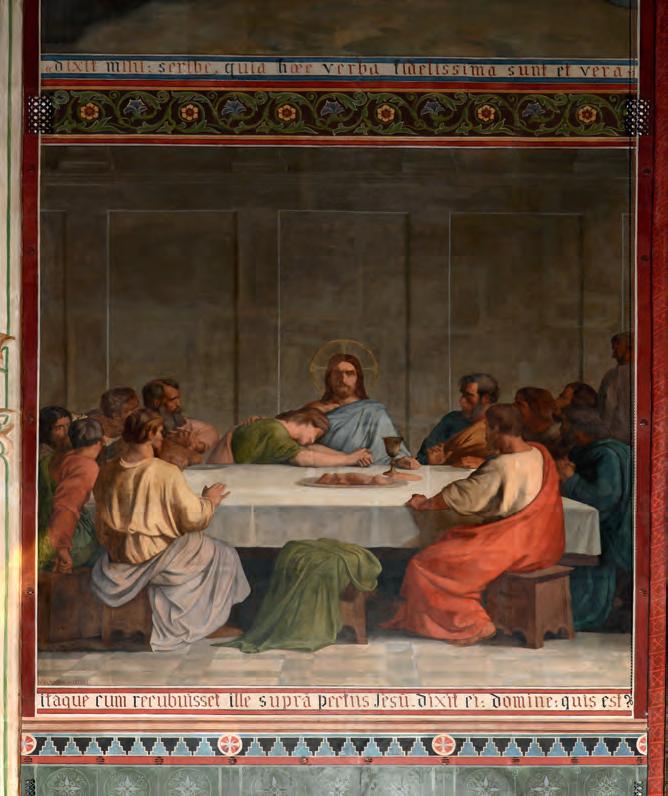

Executed possibly pre 1515. Recorded by Domenico Pino, the author of the first monograph dedicated entirely to Leonardo’s Cenacolo, the Prior of the monastery for which the original Last Supper was made. Written in 1796 as located in the Santa Maria Delle Grazie di Milano and in Guillon as “…l’autre petit, et non moins ancienne, mais peinte sur bois…elle était au temps du P. Pino dans le chambre de l’un de ses confreres”. Imperial seal of the royal academy, Milan. Christies London June 7 1856 as Lionardo da Vinci.. Gift of John Law to St Wilfrid’s Convent. The reverse with ancient parchment (papal bull?) and numerous wax seals. 36 cm x 65 cm. £20,000-30,000

Property of The Daughters of the Cross. 16th century. Oil on panel. An extraordinarily rare depiction of Leonardo’s La Cenacolo

VIII THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE | 165 | JANUARY 2023 Minerva magazine showcases the beauty and sophistication of ancient civilisations. With spectacular illustrations and exciting features, each issue will give you an inside view of the archaeology, culture, and art of the ancient world. PLUS, YOU’LL GET EVERY ISSUE DELIVERED TO YOUR DOOR VISIT www.minervamagazine.com/BurlHalf CALL 020 8819 5580 quoting ‘BurlHalf’ SUBSCRIBE TODAY, AND GET A 1 -YEAR SUBSCRIPTION FROM JUST £ 1 4.99 (USUALLY £31.95) introductory half-price offer for BURLINGTON readers OFFERSPECIAL SUBSCRIBE TODAY aestheticamagazine.com The Destination for Art and Culture SUBSCRIBE & SAVE 70% 12 MONTHS FOR £12 (+P&P) Offer ends 31 January 2023

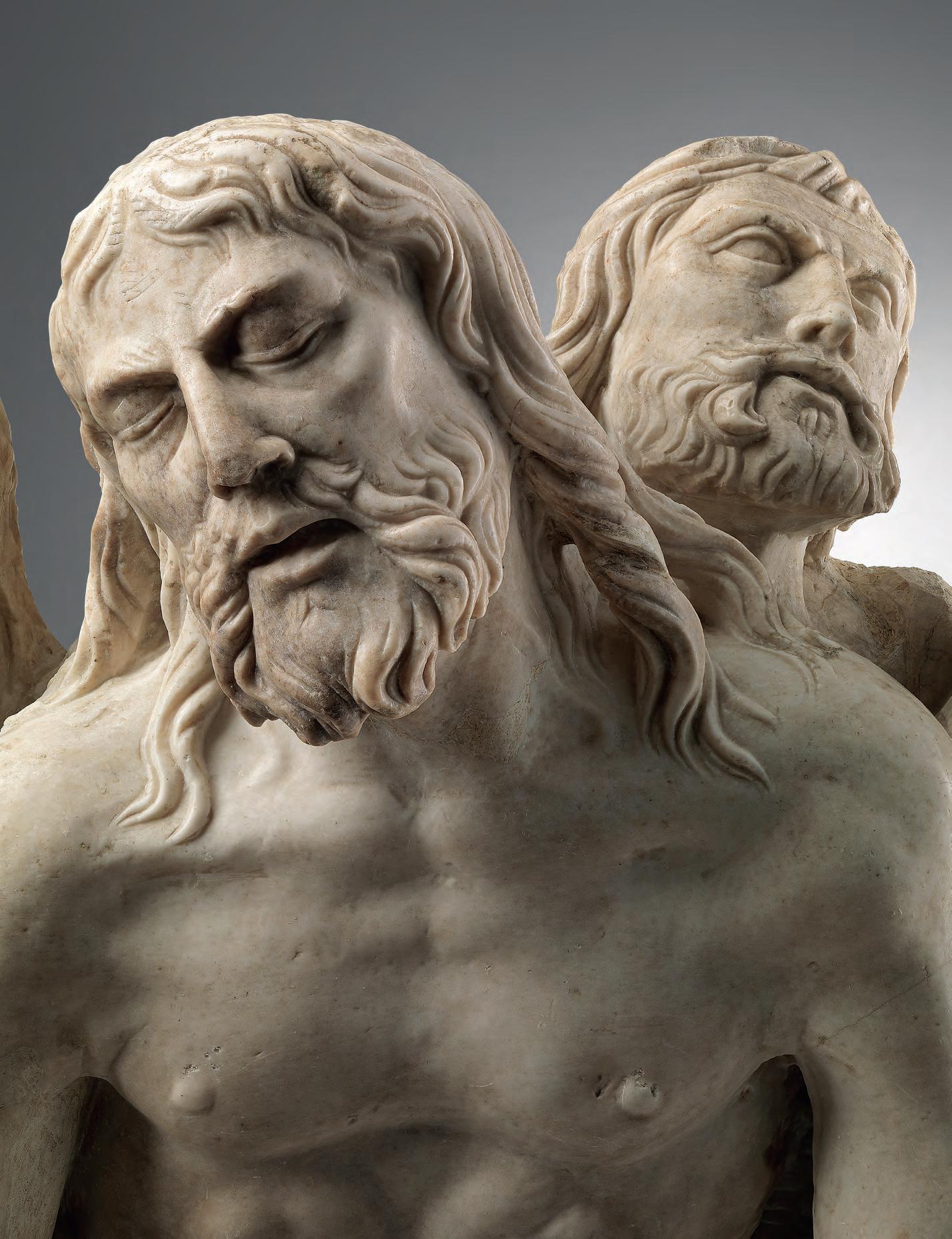

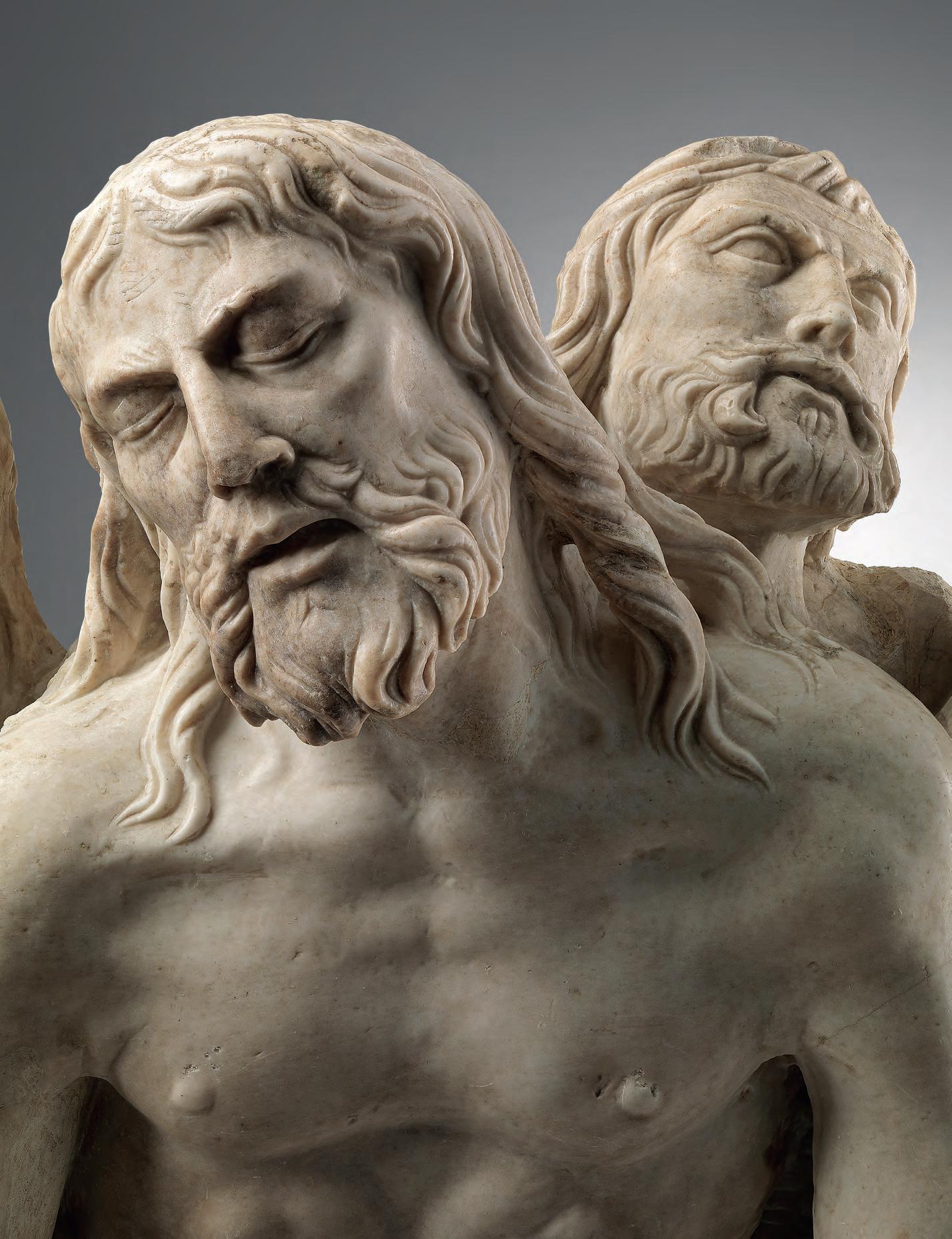

Gasparo Cairano Deposition Group (detail) alabaster 47,5 x 65 x 22,5 cm CARLO ORSI Old Master Paintings and Sculpture

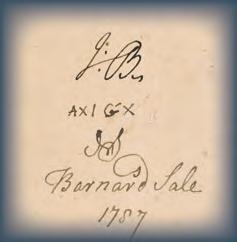

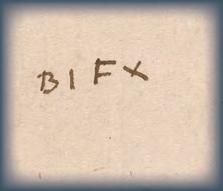

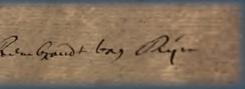

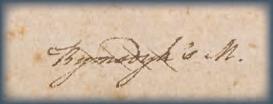

THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE | 165 | JANUARY 2023 X CONT @ CTS owse and b one-of-a-kind items online ms m 11 Duke Street | St James’ | London SW1Y 6BN Tel. +44 207 930 1144 | Fax. +44 207 976 1596 www.rafaelvalls.co.uk | info@rafaelvalls.co.uk Daniel Katz G allery from antiquity to the 2oth century www.katz.art TRINITY FINE ART 15 old bond street london w 1 s 4 ax www.trinityfineart.com info @ trinityfineart.com +44 (0)20 7493 4916 GROUND-BREAKING ISSUE ON COLLECTORS: EARLY INSCRIPTIONS AND SECRET CODES vol. 60-4 2023-Burlington Mag.indd 1 11/12/2022 10:58 CONT @ CTS Browse one-of-a-kind day & faber old master drawings www.dayfaber.com m 11 Duke Street | St James’ | London SW1Y 6BN Tel. +44 207 930 1144 | Fax. +44 207 976 1596 www.rafaelvalls.co.uk | info@rafaelvalls.co.uk Daniel Katz G from antiquity to the 2oth century www.katz.art m TRINITY FINE ART 15 old bond street london w 1 s 4 ax www.trinityfineart.com info @ trinityfineart.com +44 (0)20 7493 4916 NEW RARITET GALLERY OLD MASTER PAINTINGS From Renaissance to the 20th Century www.newraritetgallery.com 38 & 39 DUKE STREET, ST JAMES’S, LONDON +44 2078395666 WWW.PETERFINER.COM CONT @ CTS uy owse and b Br one-of-a-kind items online ms faber drawings century ART trinityfineart.com 4916 GALLERY Century To advertise please visit: burlington.org.uk day & faber old master drawings www.dayfaber.com m 11 Duke Street | St James’ | London SW1Y 6BN Tel. +44 207 930 1144 | Fax. +44 207 976 1596 www.rafaelvalls.co.uk | info@rafaelvalls.co.uk m m NEW RARITET GALLERY OLD MASTER PAINTINGS From Renaissance to the 20th Century www.newraritetgallery.com uy owse and b Br one-of-a-kind items online ms day & faber old master drawings www.dayfaber.com m 11 Duke Street | St James’ | London SW1Y 6BN Tel. +44 207 930 1144 | Fax. +44 207 976 1596 www.rafaelvalls.co.uk | info@rafaelvalls.co.uk Daniel Katz G allery from antiquity to the 2oth century www.katz.art m TRINITY FINE ART 15 old bond street london w 1 s 4 ax www.trinityfineart.com info @ trinityfineart.com +44 (0)20 7493 4916 NEW RARITET GALLERY OLD MASTER PAINTINGS From Renaissance to the 20th Century www.newraritetgallery.com

2023 SCHOLARSHIP

INVITATION FOR APPLICATIONS

The Burlington Magazine is pleased to announce its sixth annual scholarship which has been created to provide funding over a 12-month period to those engaged in the study of French 18thcentury fine and decorative art to enable them to develop new ideas and research that will contribute to this field of art historical study. Applicants must be studying, or intending to study, for an MA, PhD, post-doctoral or independent research in this field within the 12-month period the funding is given. Applications are open to scholars from any country. A grant of £10,000 will be awarded to the successful applicant. Deadline for applications is 17 March 2023 and the successful applicant will be notified by 31 May 2023. For application guidelines and terms and conditions please visit www.burlington.org.uk

THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE | 165 | JANUARY 2023 XI Theleadingpeer-reviewedjournal dedicatedtotheartoftheprint www.printquarterly.co.uk PRINT QUARTERLY ADVERTISESUBSCRIBEPUBLISH Read The Art Newspaper anywhere, anytime Save 50% on a digital subscription

Subscribe

Enter

sale More

O ers are

the

The Art Newspaper has been making sense of the art world for more than 30 years. We don’t simply write about art – our news relates to current events and how those a ect the international landscape of art and culture at large, from politics and the economy to technology and the environment. Save 50% when you purchase a Digital subscription and get seamless access to all our content via our website, apps for Apple and Android mobile device and an ePaper archive of the monthly newspaper going back to December 2012.

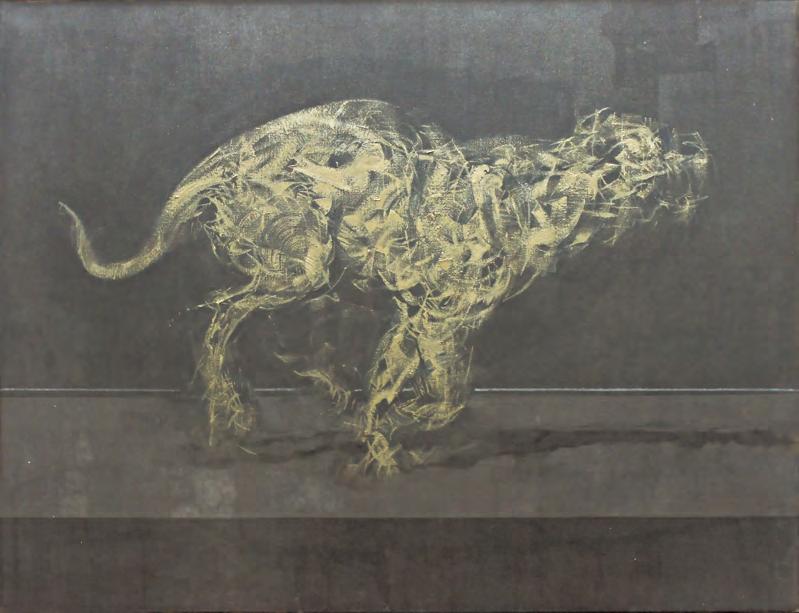

at: theartnewspaper.com/ subscription-o ers

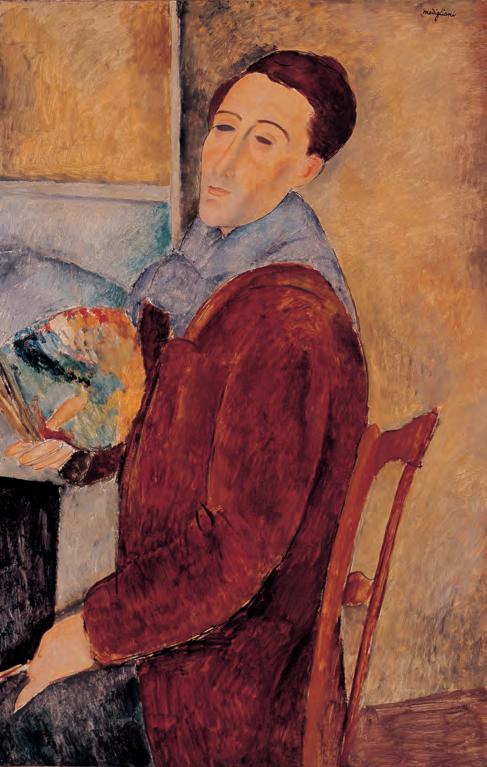

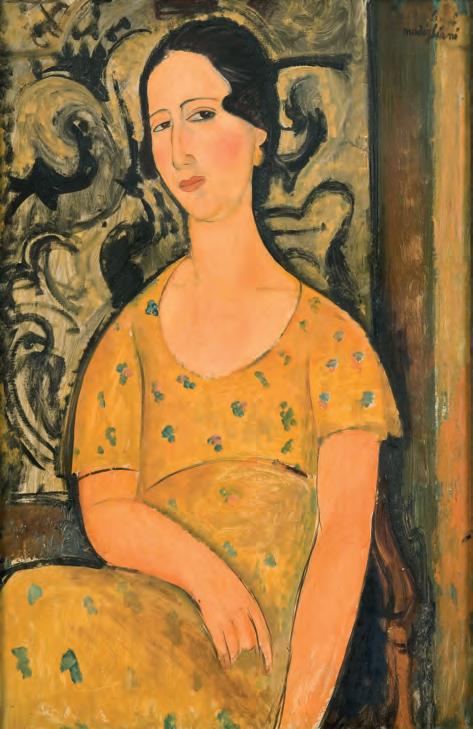

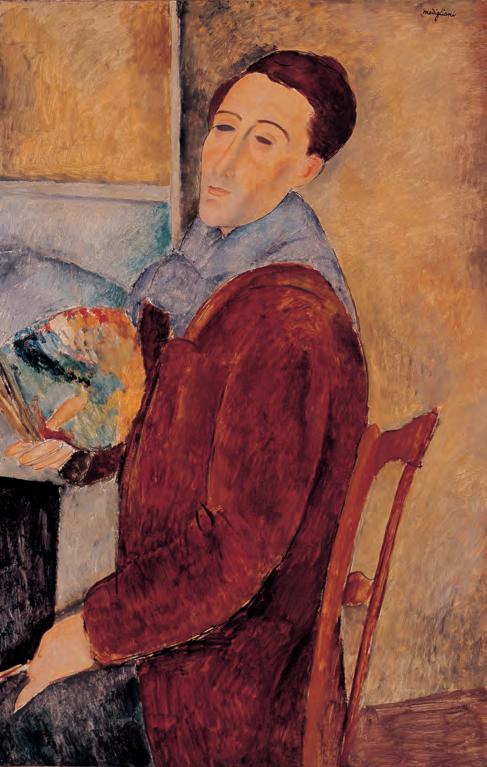

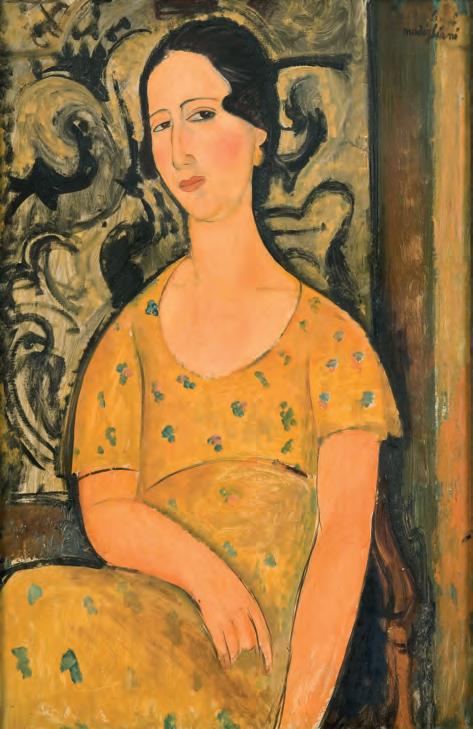

code: BURLINGTON Modigliani portrait from the artist’s rst creative period in Paris for

to know at: www.modigliani-portrait.com

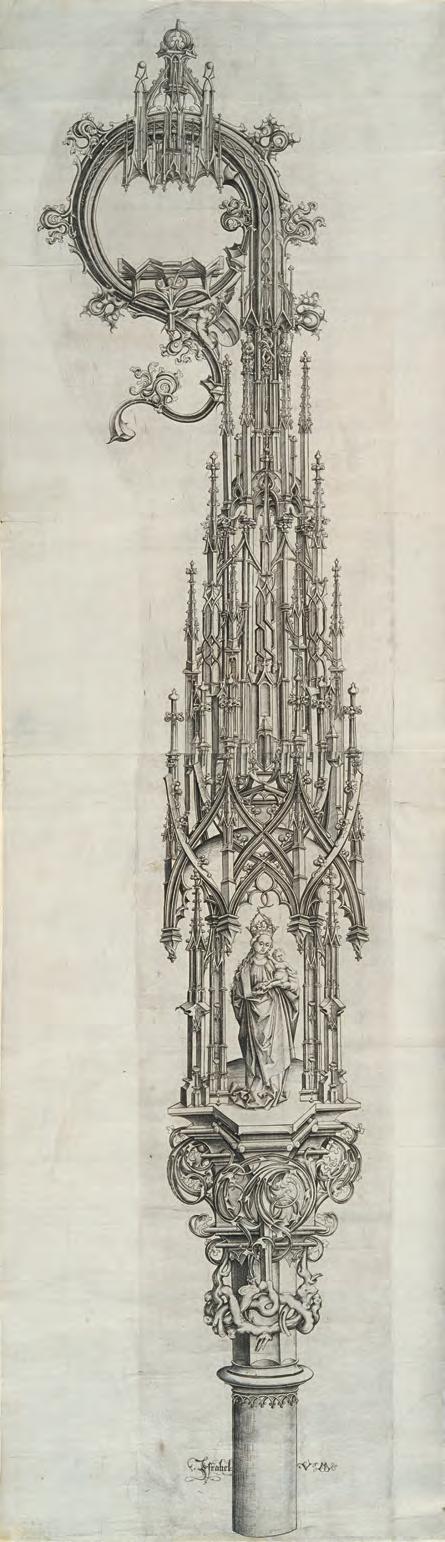

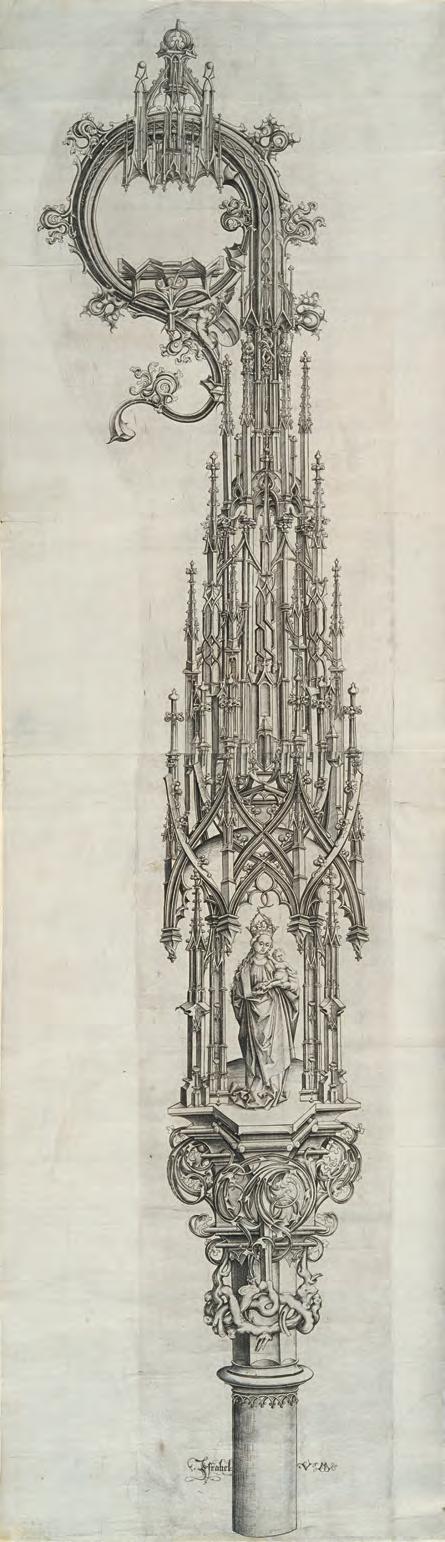

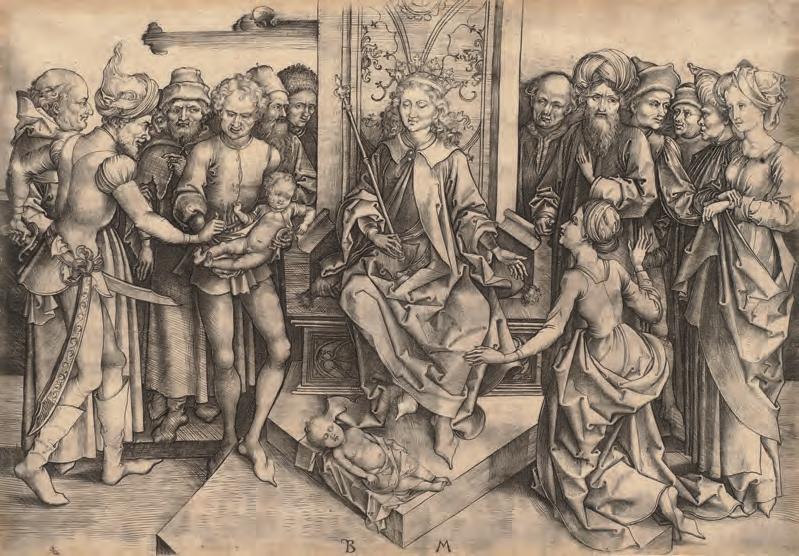

invited by using

contact form included

for the study of French 18th-century fine and decorative art

MORETTI 13 Duke Street, St. James’s London SW1Y 6DB enquiries@morettigallery.com +44 (0)20 7491 0533

Vasari Arezzo, 1511 – Florence, 1574 The Temptation of Saint Jerome Oil on panel, 165 x 117 cm Recently sold to a private collector

Giorgio

Editorial 3 A spoonful of sugar

Articles

focus on bronzino

4 Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour re-examined by paula dredge, anne gérardaustin, daryl howard and simon ives

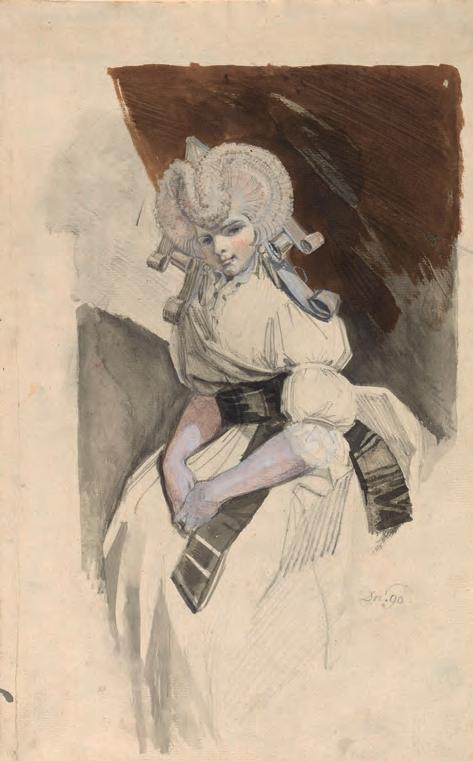

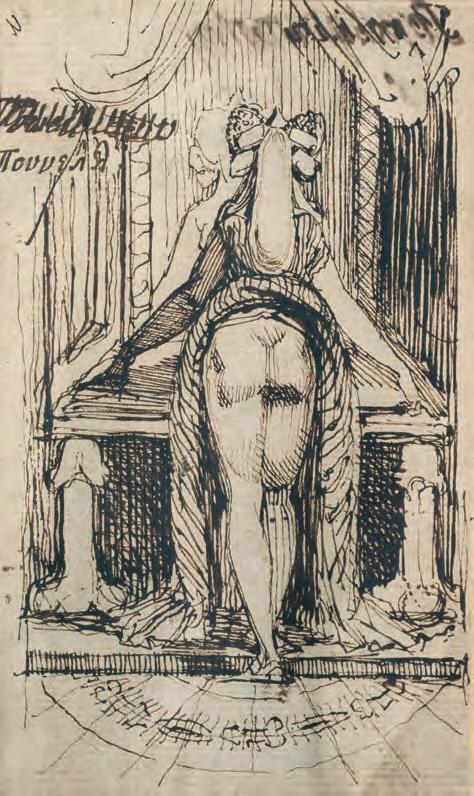

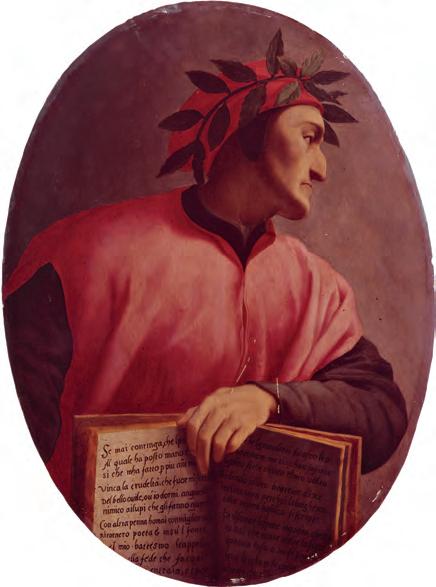

16 Bronzino’s ‘Petrarch’ retrieved: new light on Bartolomeo Bettini’s ‘camera’ by jeroen stumpel

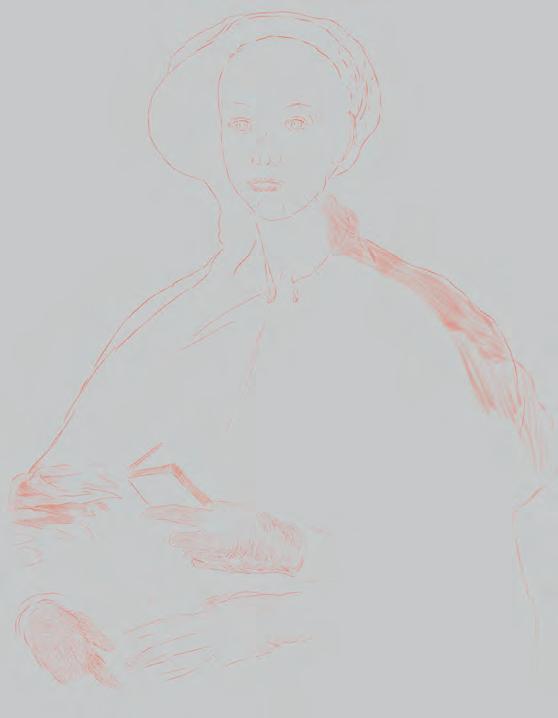

26 A portrait of the Lady Isabella by the hand of Bronzino by bruce edelstein

38 Discoveries in the Parma baptismal registers: 1 Parmigianino as godfather by mary vaccaro

42 Sicilian silver in Malta: an eighteenthcentury ciborium in Mdina by roberta cruciata

A rticle reviews

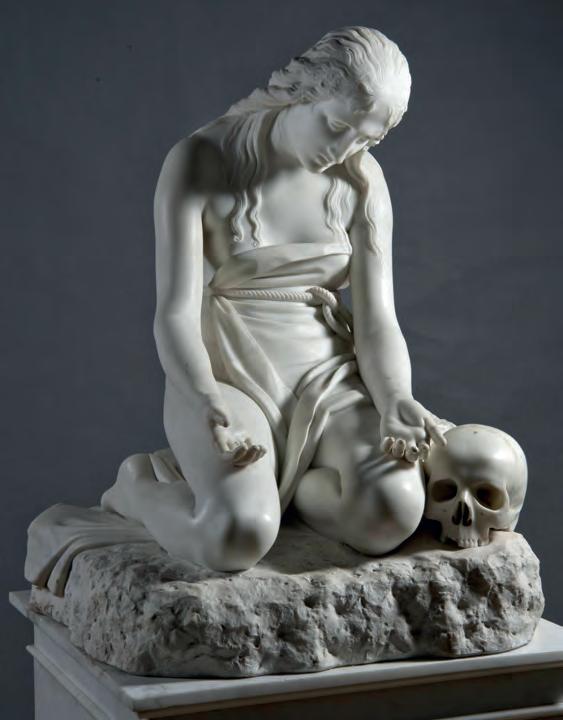

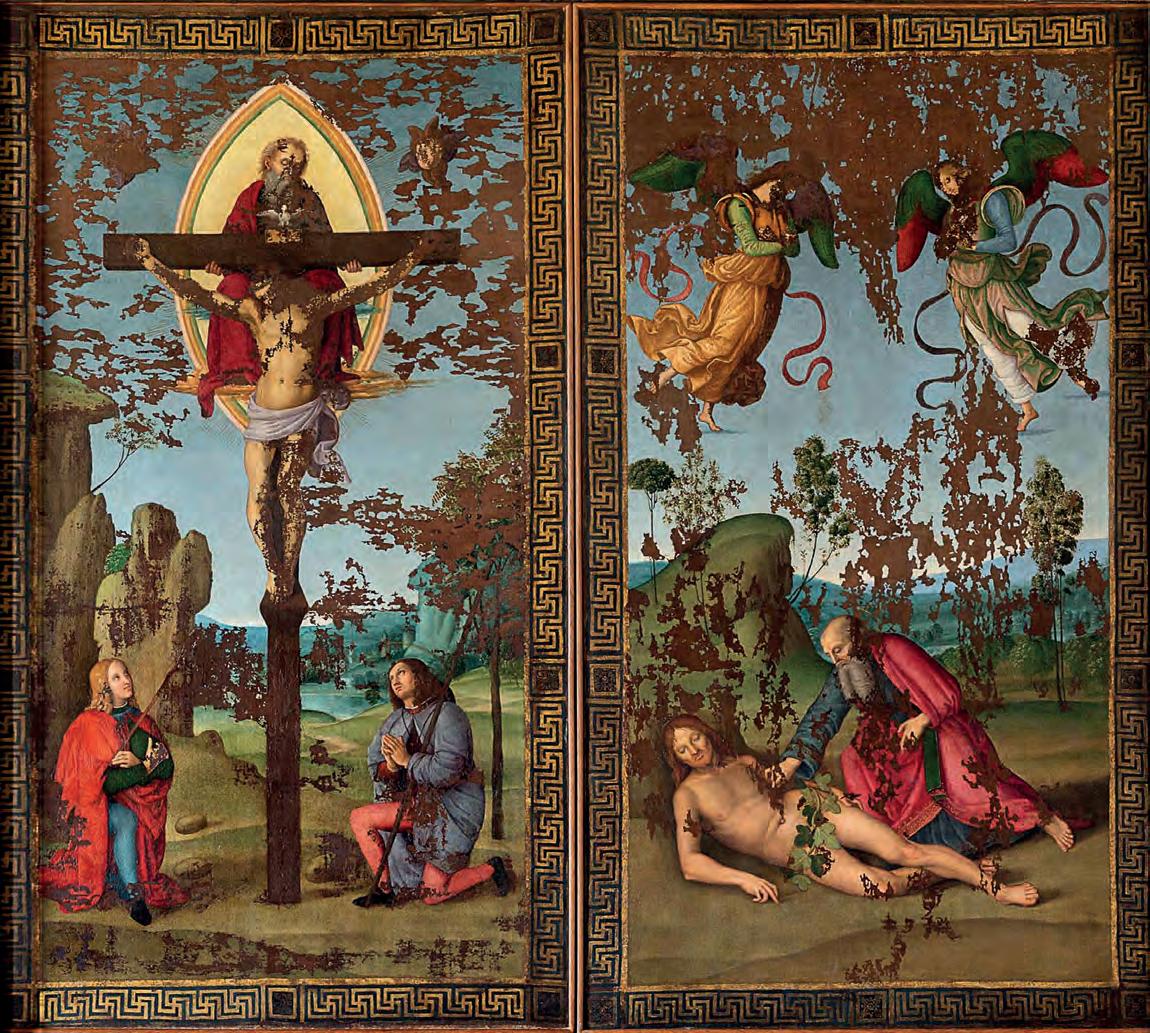

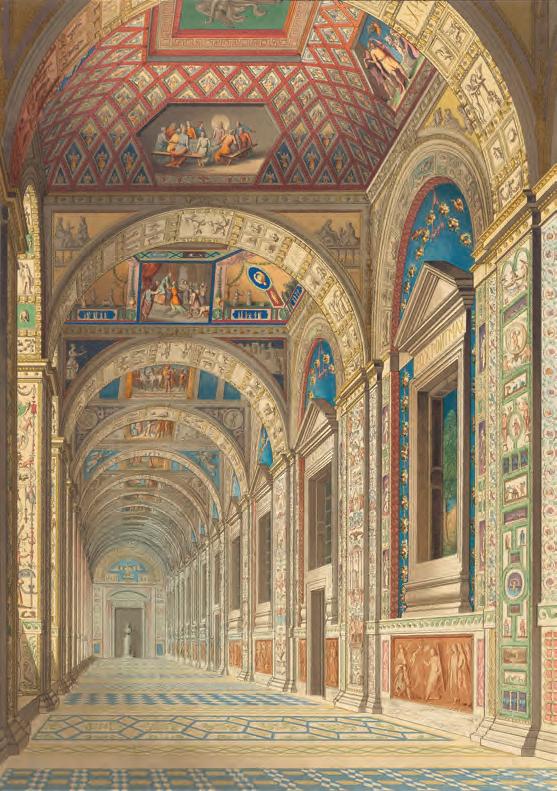

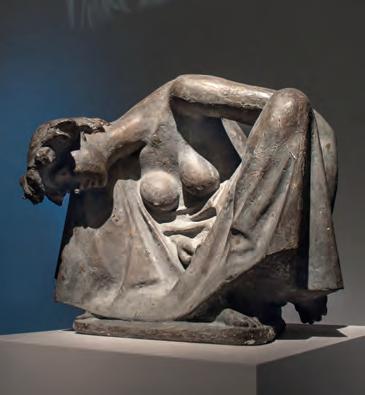

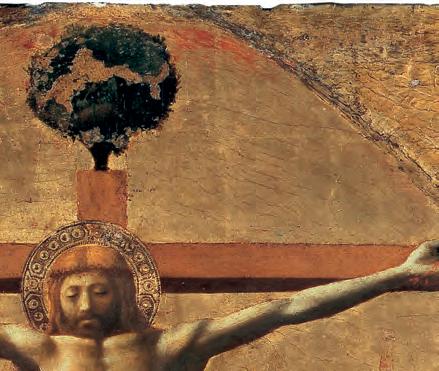

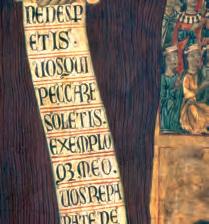

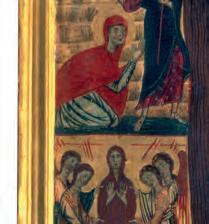

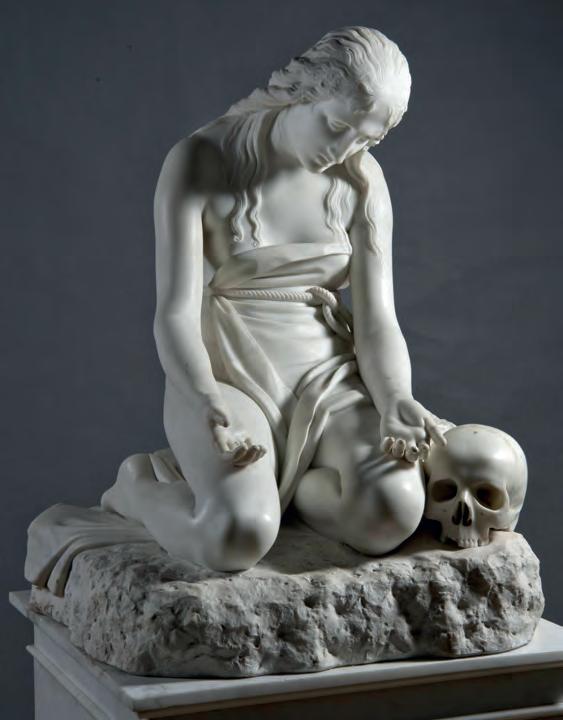

50 The many faces of Mary Magdalene by susan haskins 57 The man who never was – almost by arnold nesselrath

Exhibitions

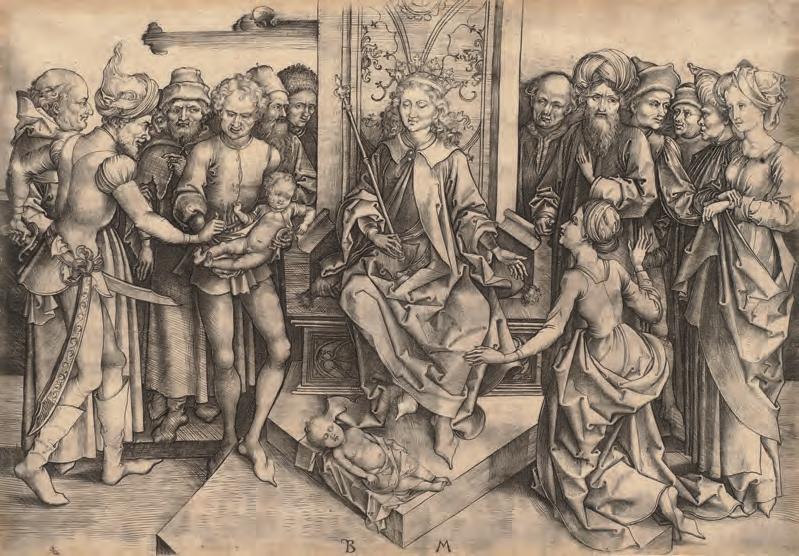

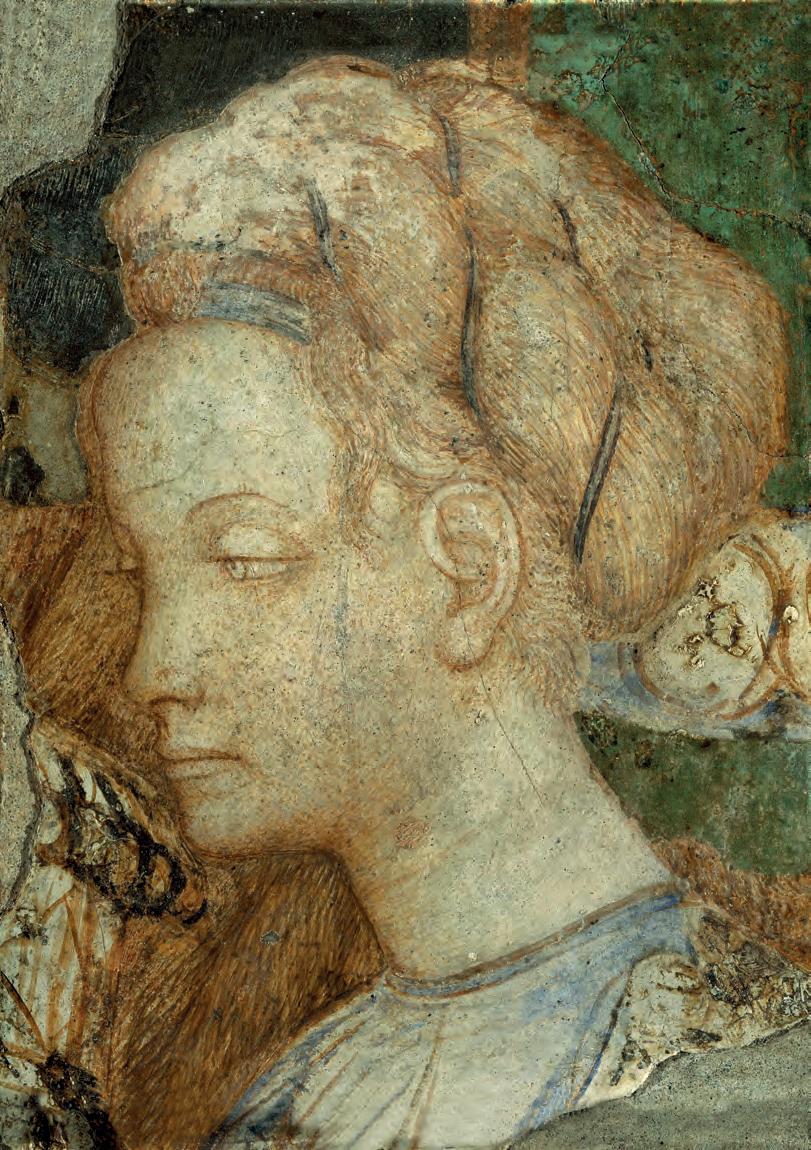

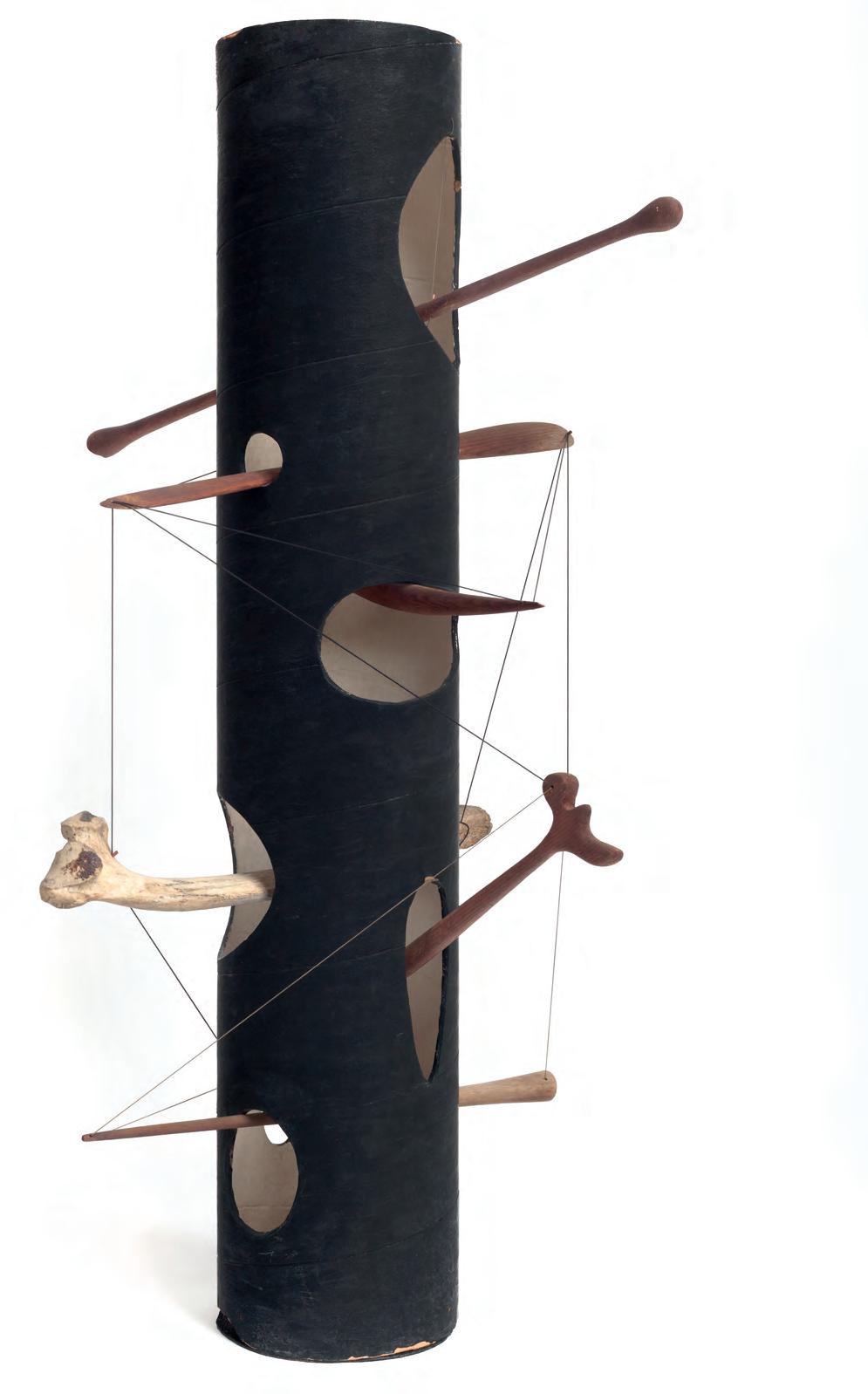

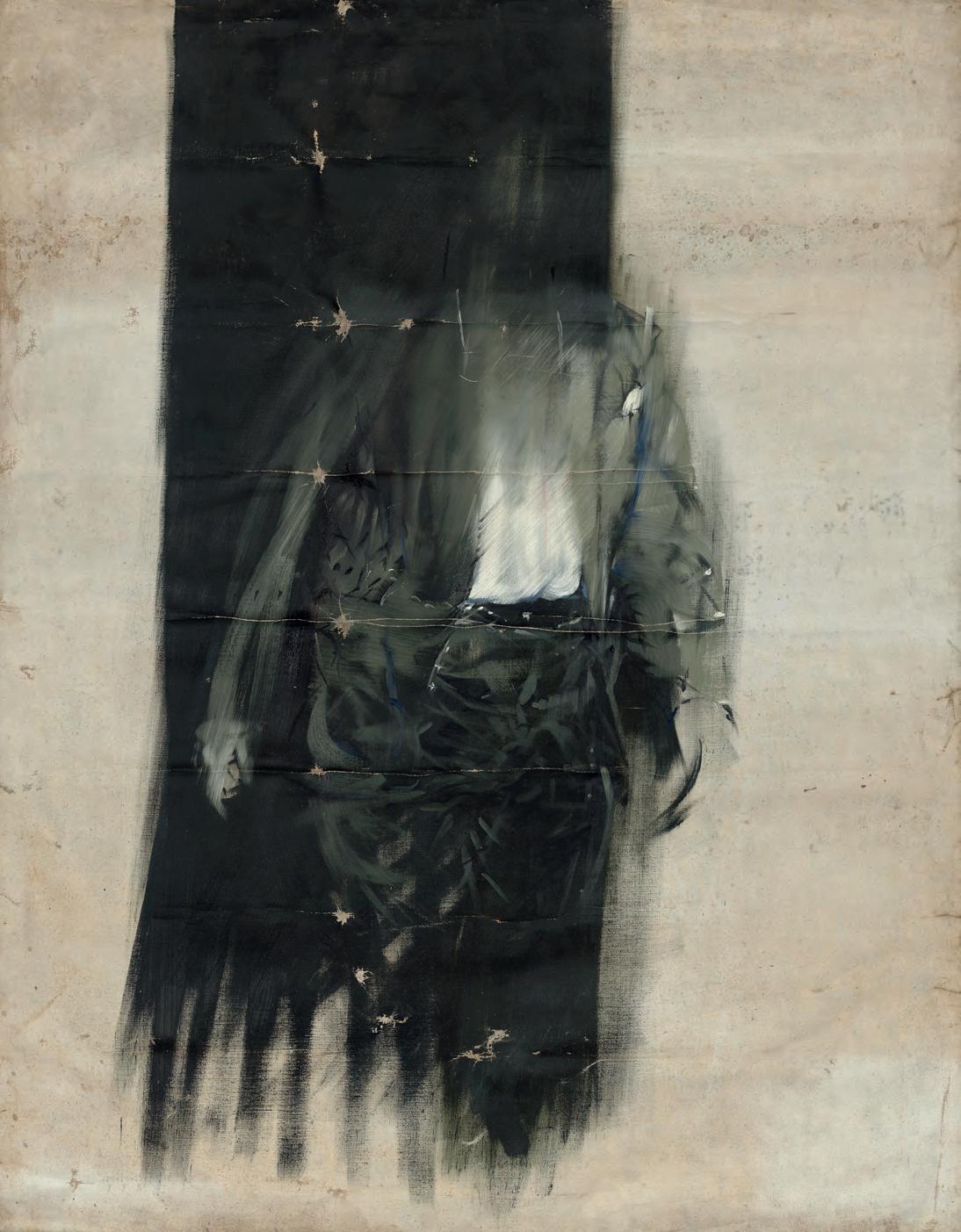

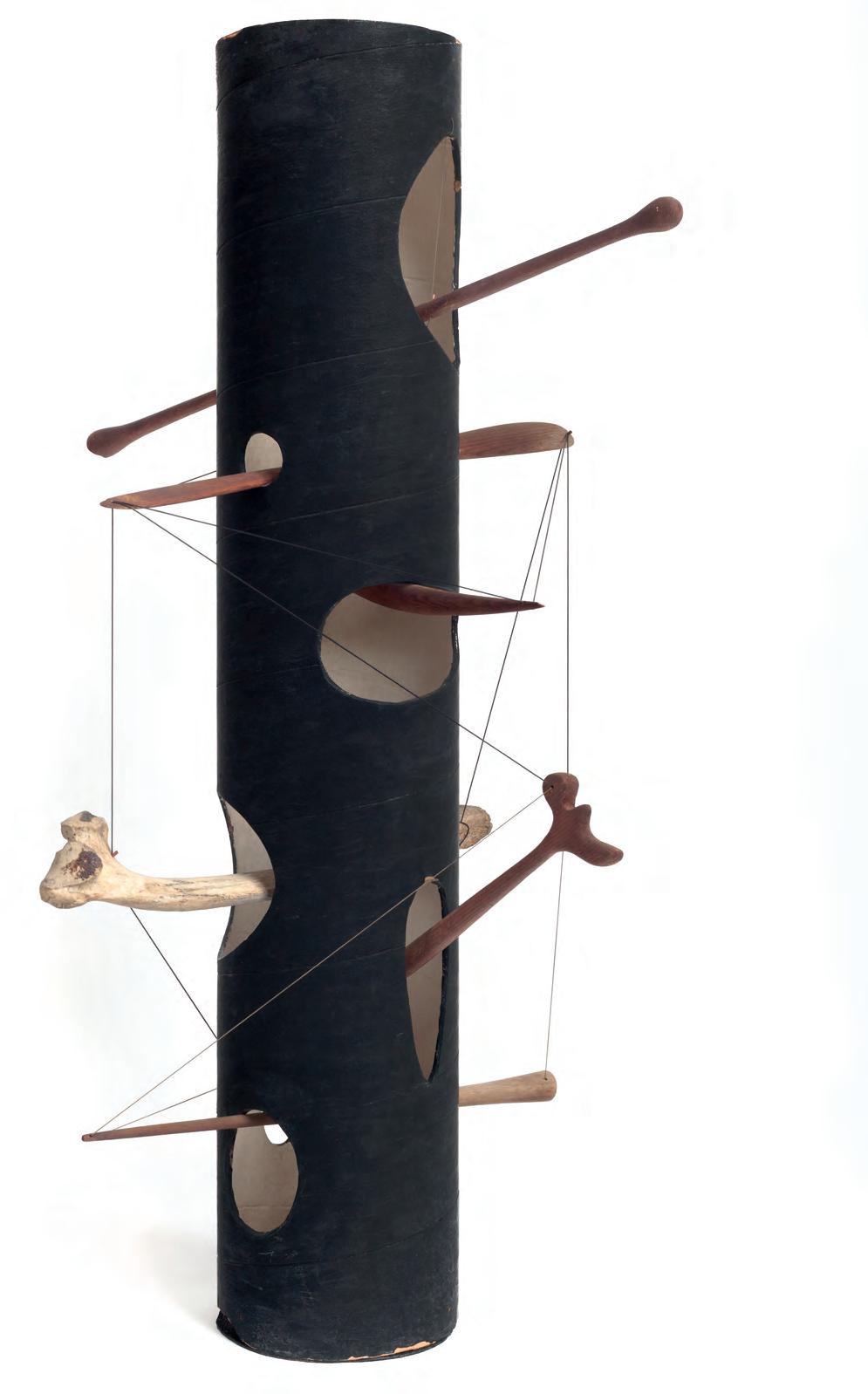

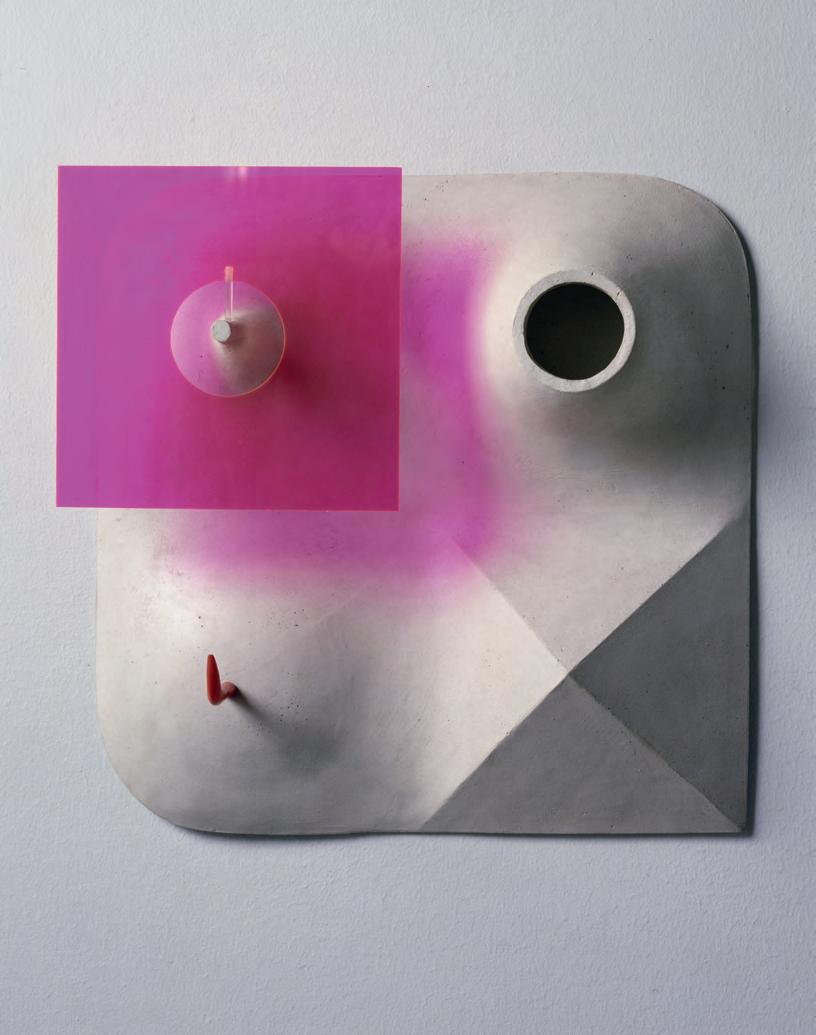

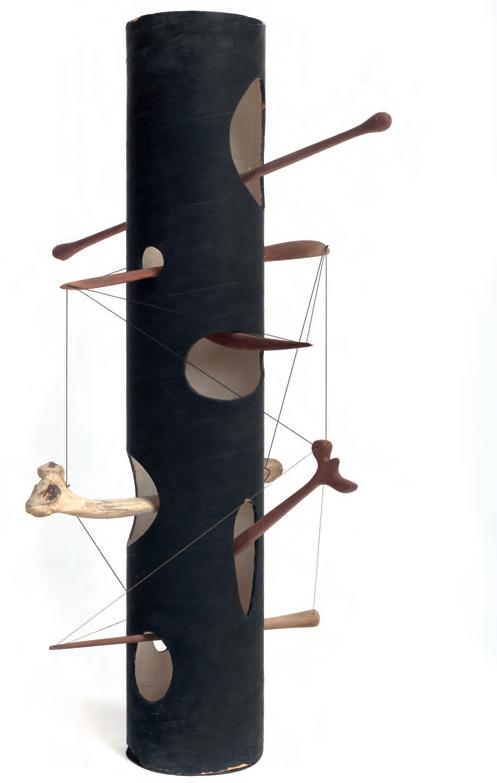

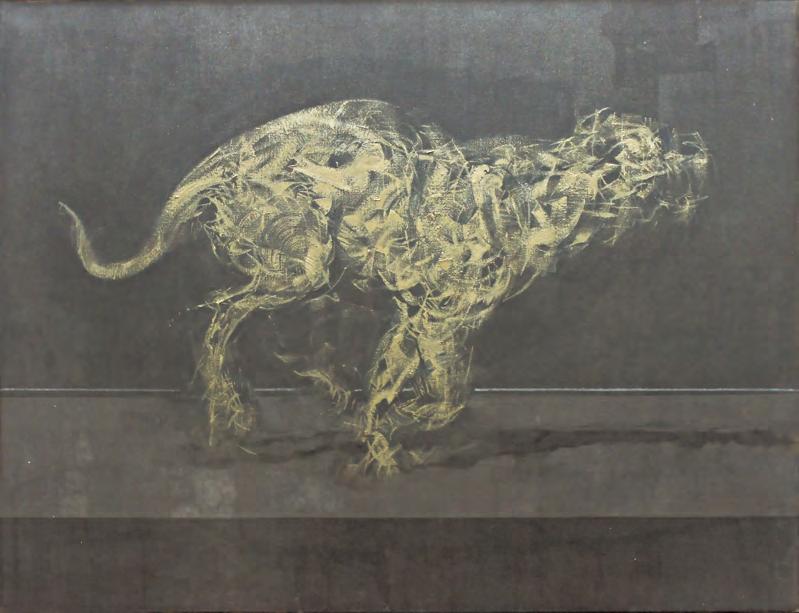

66 Denis Wirth-Miller: Landscapes and Beasts by katharina günther 69 Vor Dürer: Kupferstich wird Kunst by armin kunz 71 Pisanello: Il Timulto del Mondo by samuel dawson 74 The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England by elizabeth goldring 77 Der Maler als Zeichner – der Zeichner als Maler: 300 Jahre Johann Heinrich Tischbein d. Ä. by heidrun ludwig 79 Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism by kevin salatino 81 Modigliani Up Close by bart j.c. devolder 83 Morris Hirshfield Rediscovered by randall morris 86 Isamu Noguchi by penelope curtis

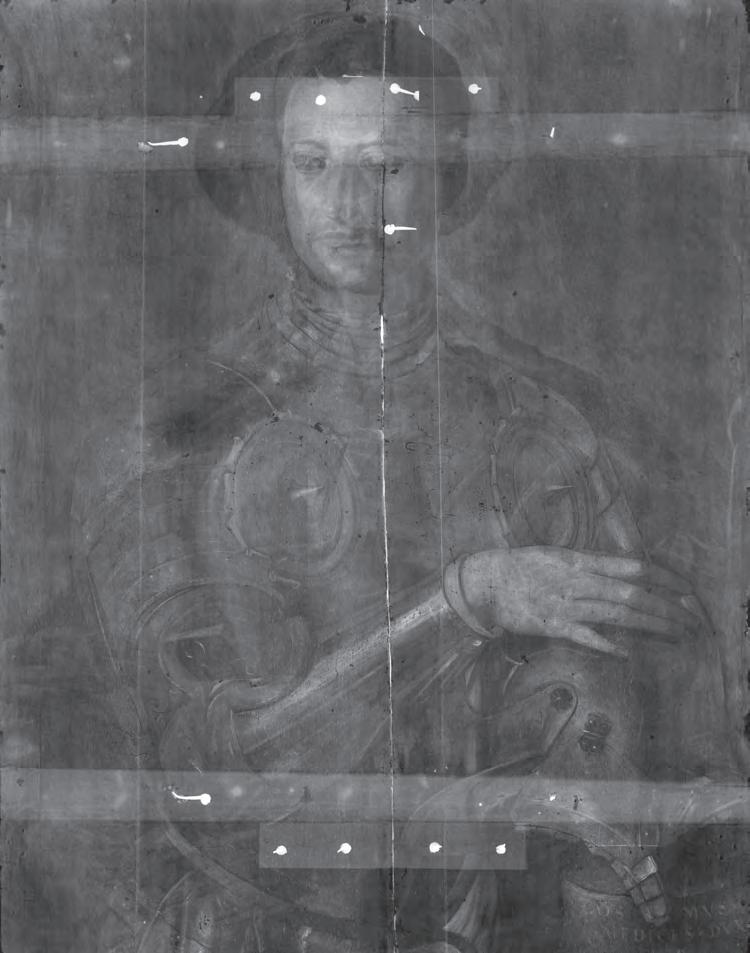

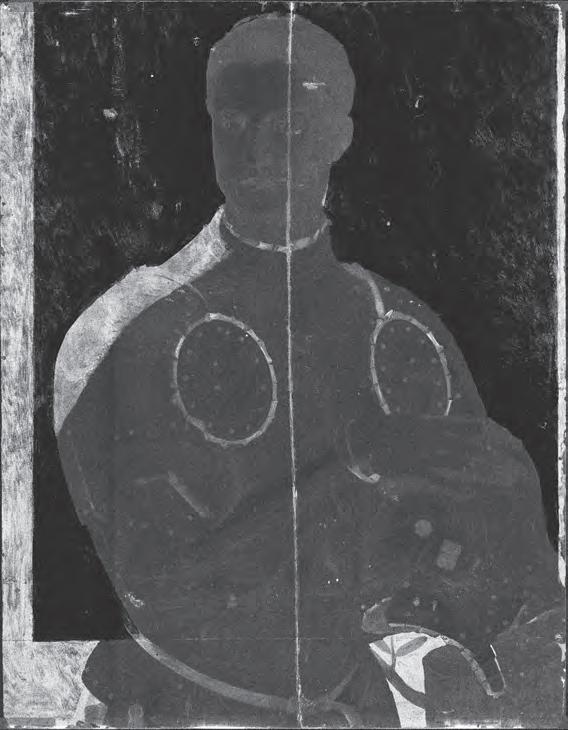

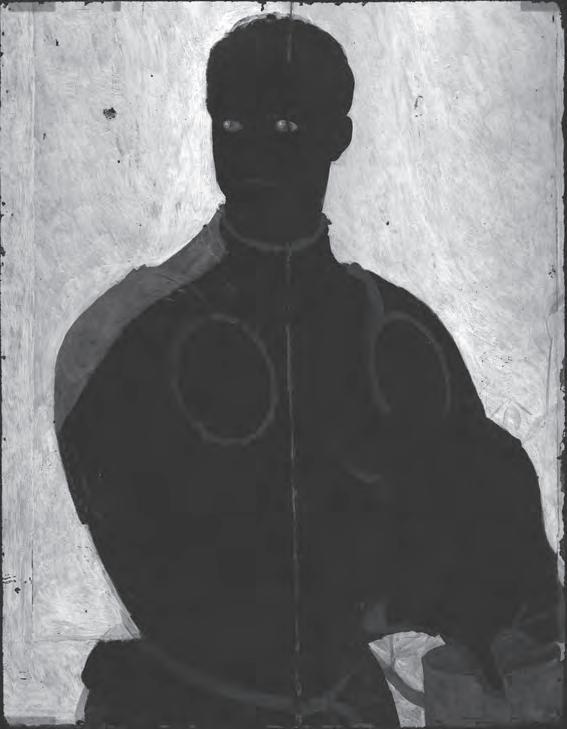

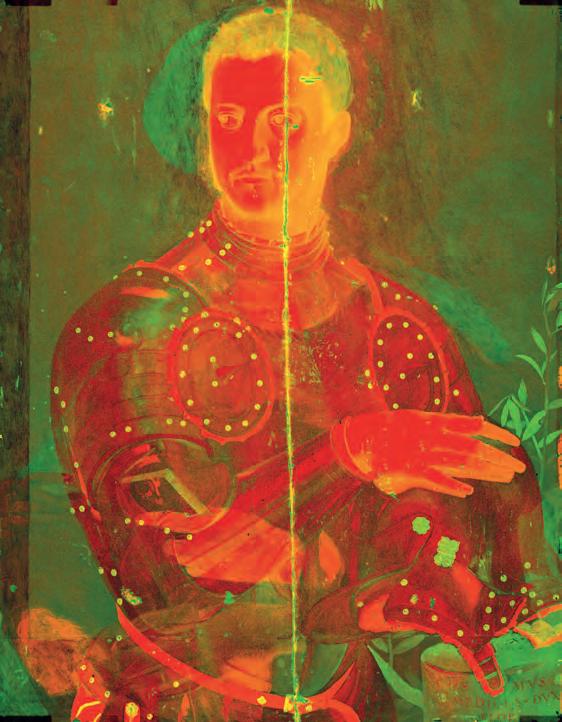

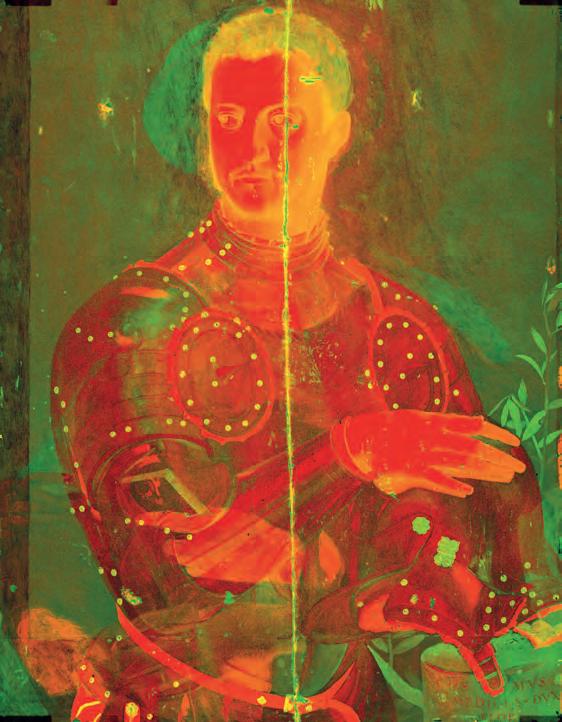

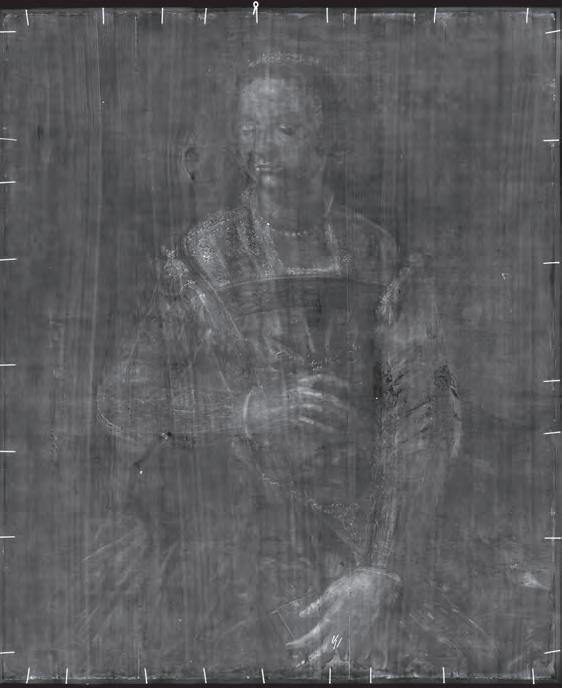

Cover Detail of a composite XRF scan map of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour, by Agnolo Bronzino. c.1545. (p.13).

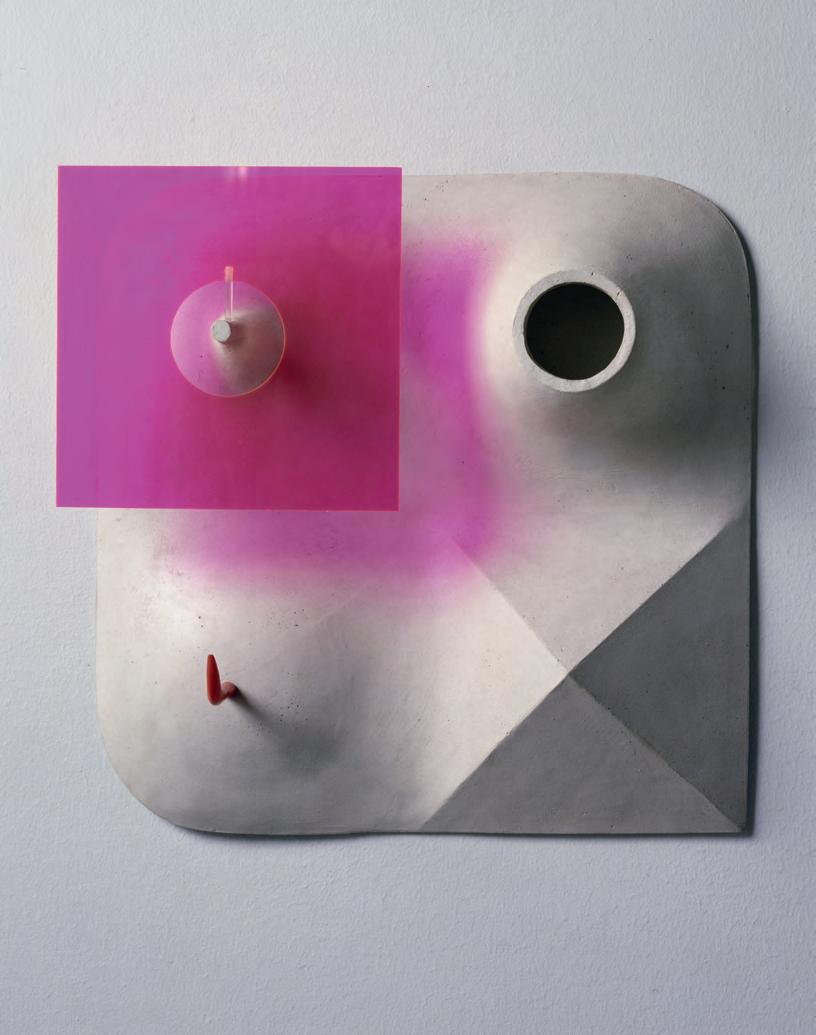

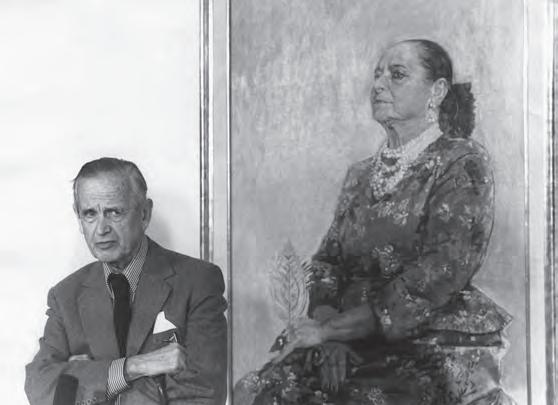

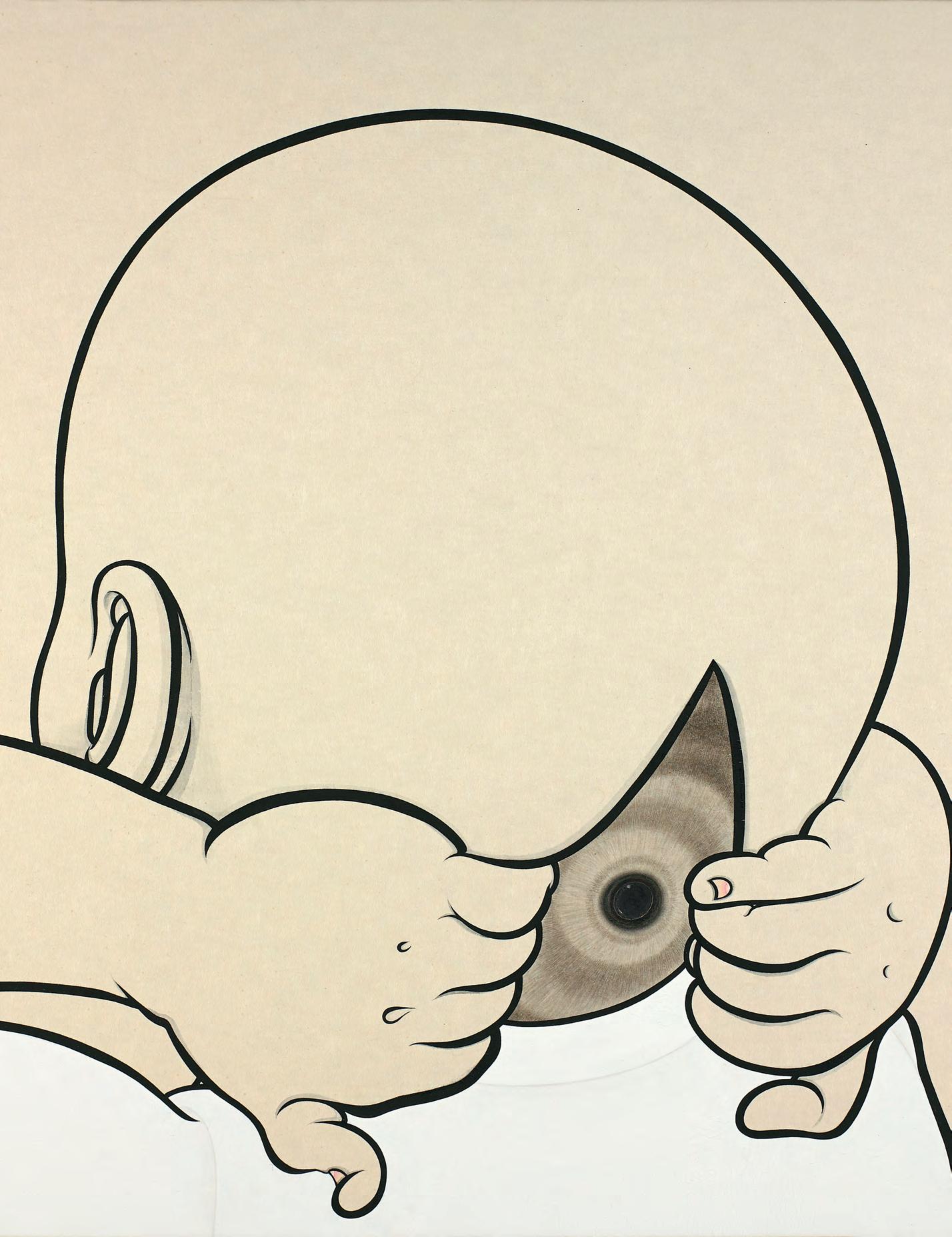

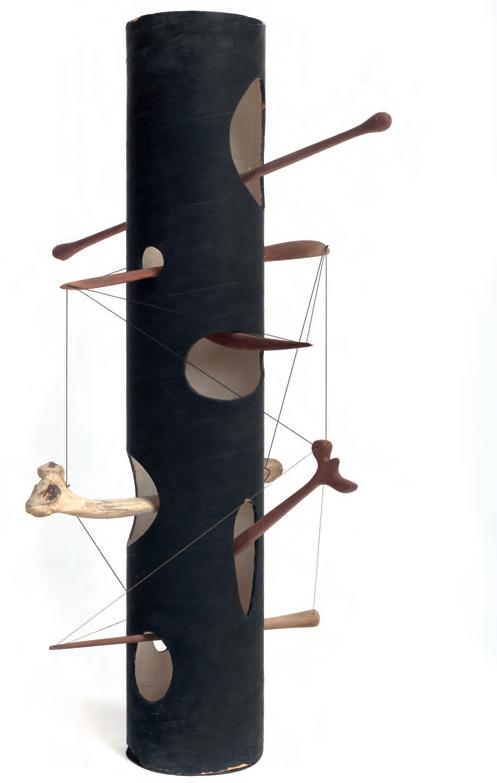

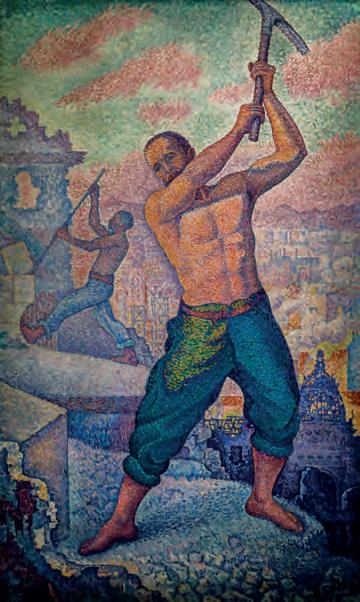

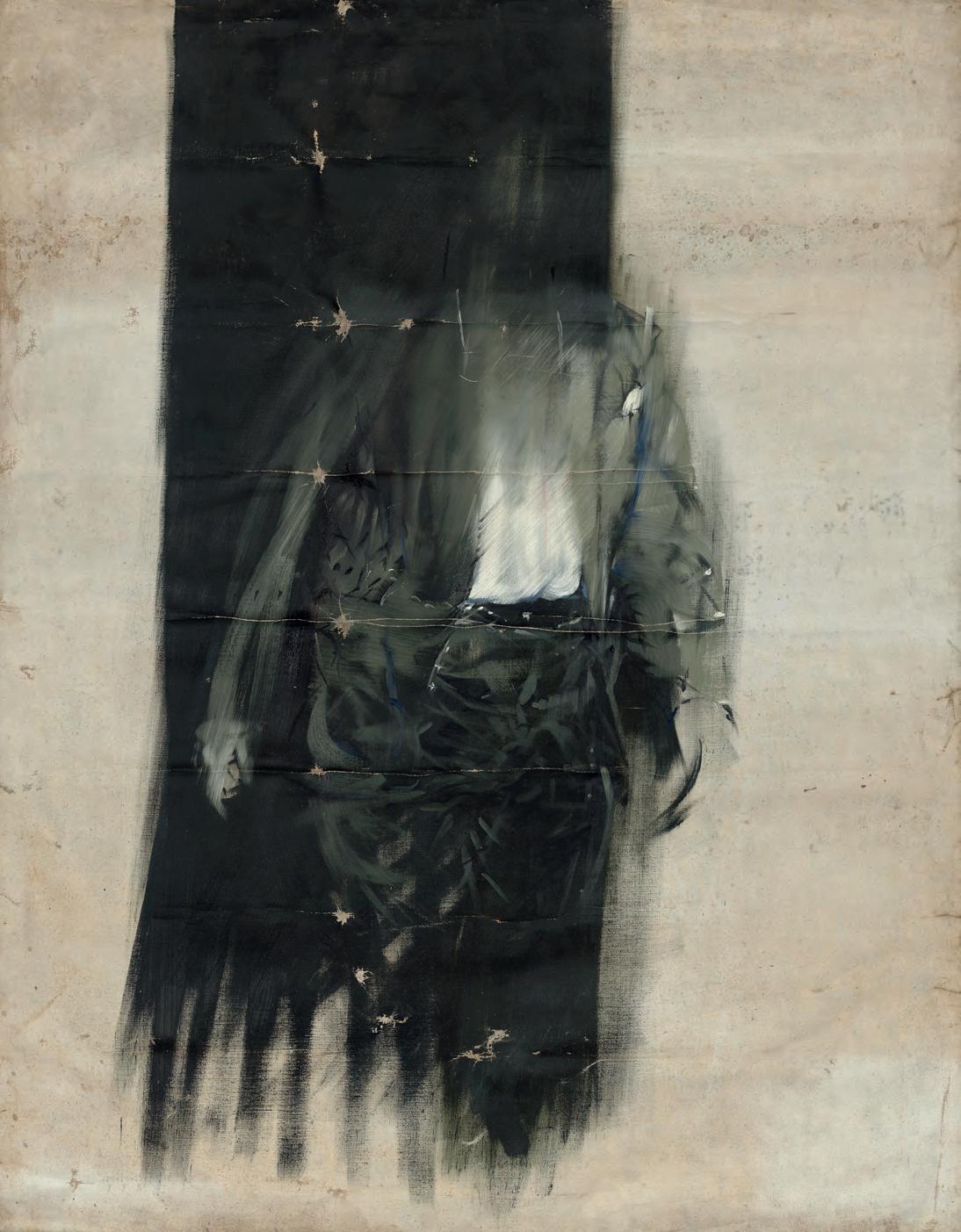

Left Monument to heroes, by Isamu Noguchi. 1943. (p.88).

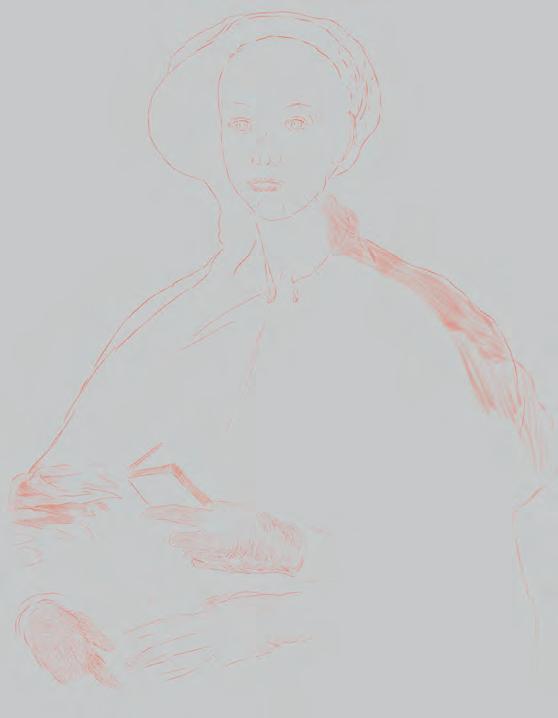

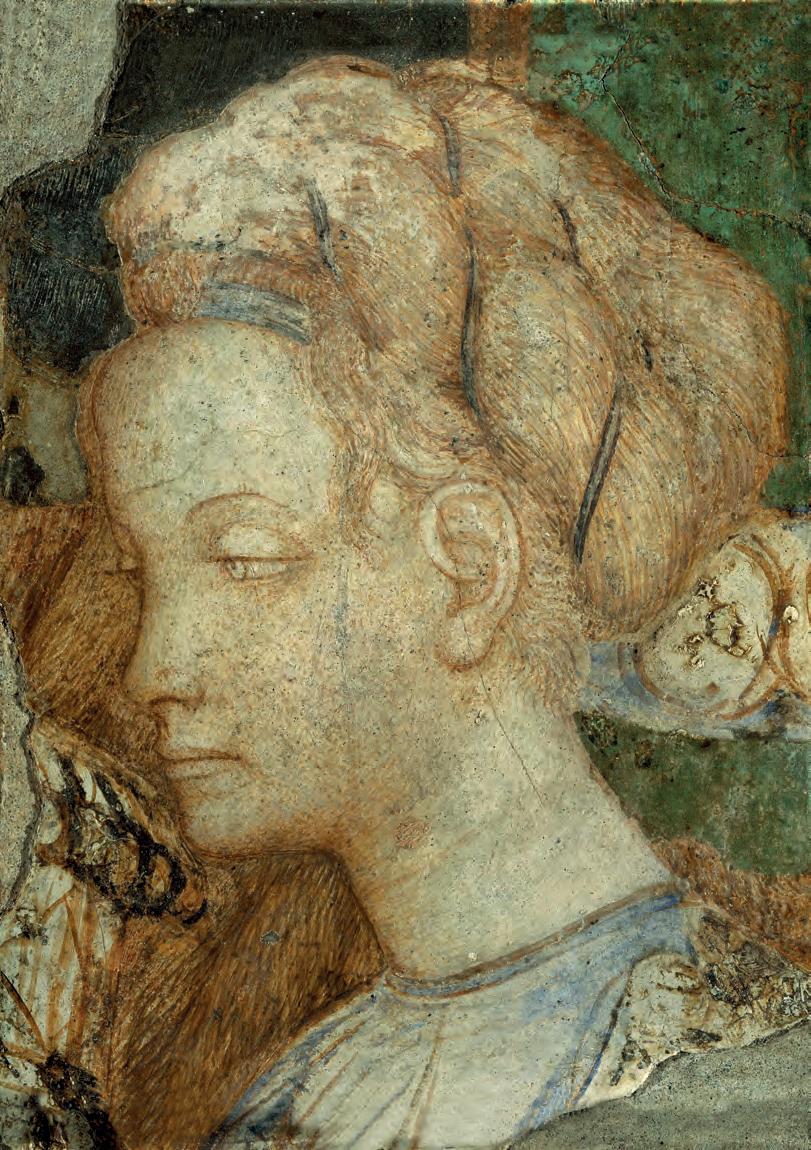

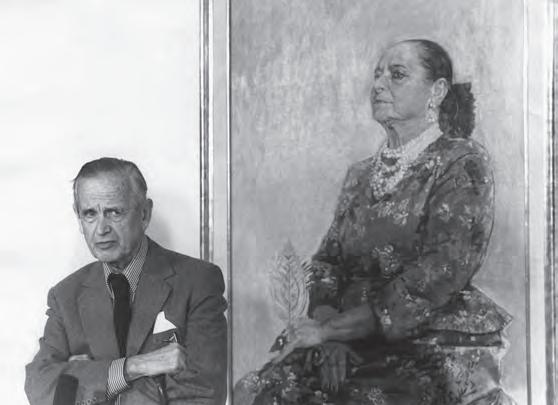

Above Detail of Portrait of a woman, by Agnolo Bronzino. c.1560. (p.27).

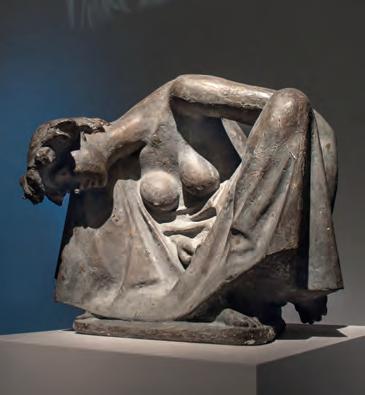

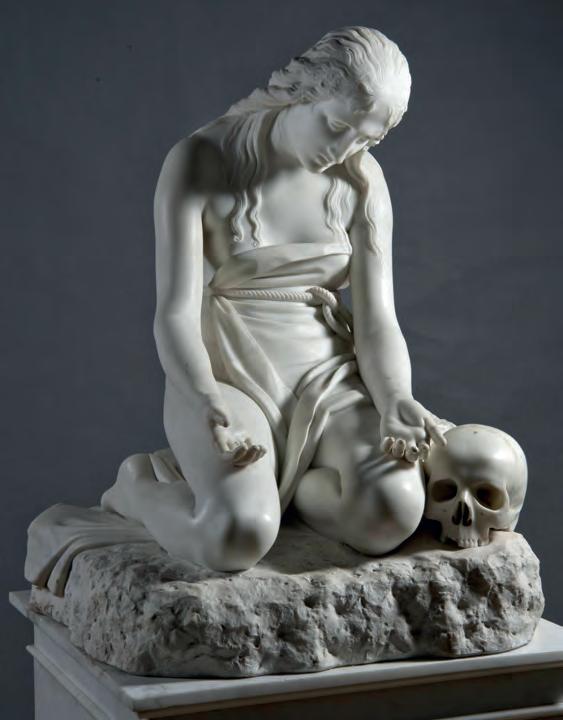

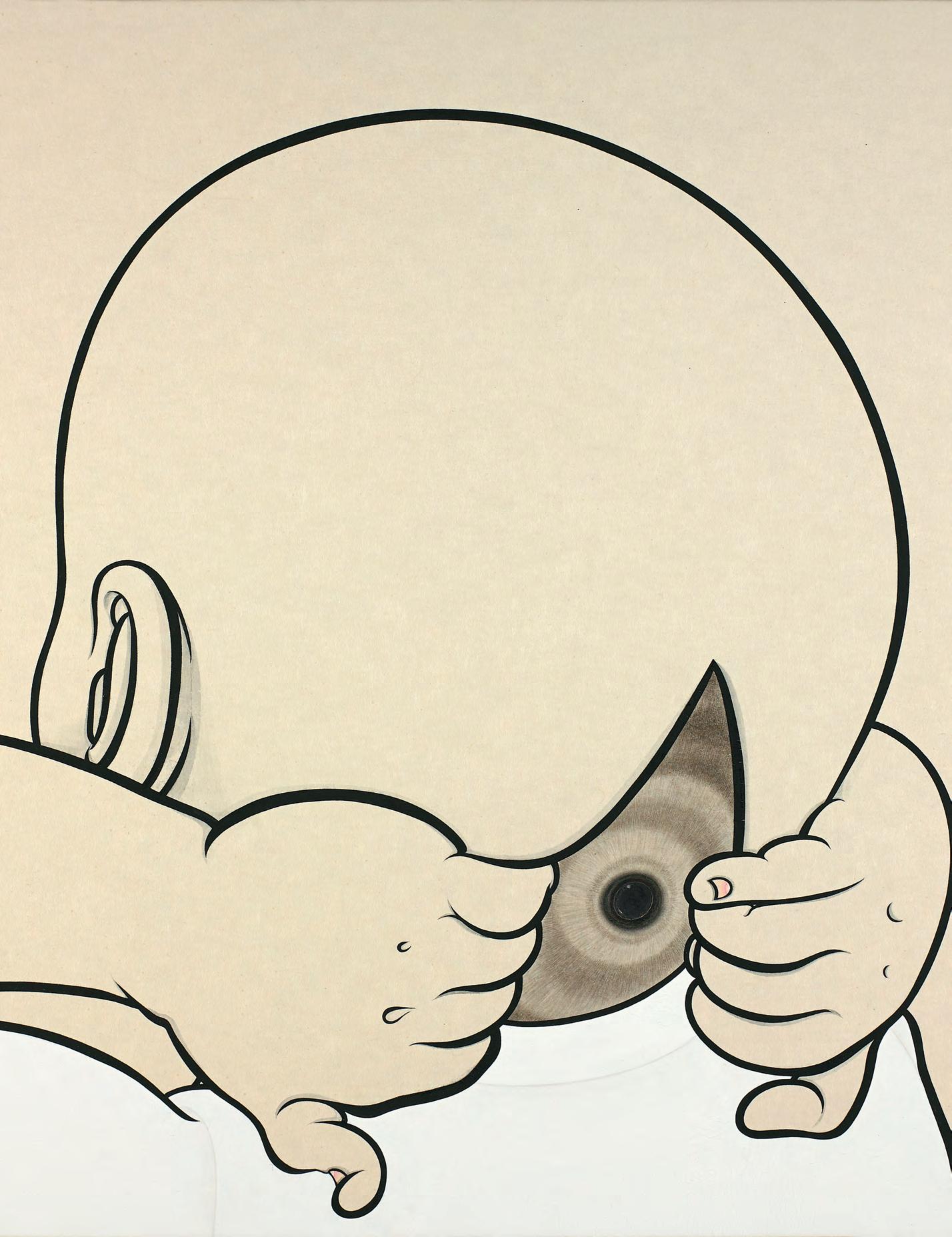

Right Mary Magdalene crouching, by Venanzo Crocetti. 1956. (p.56).

Books

90 Artemisia Gentileschi, S Barker by mary d. garrard

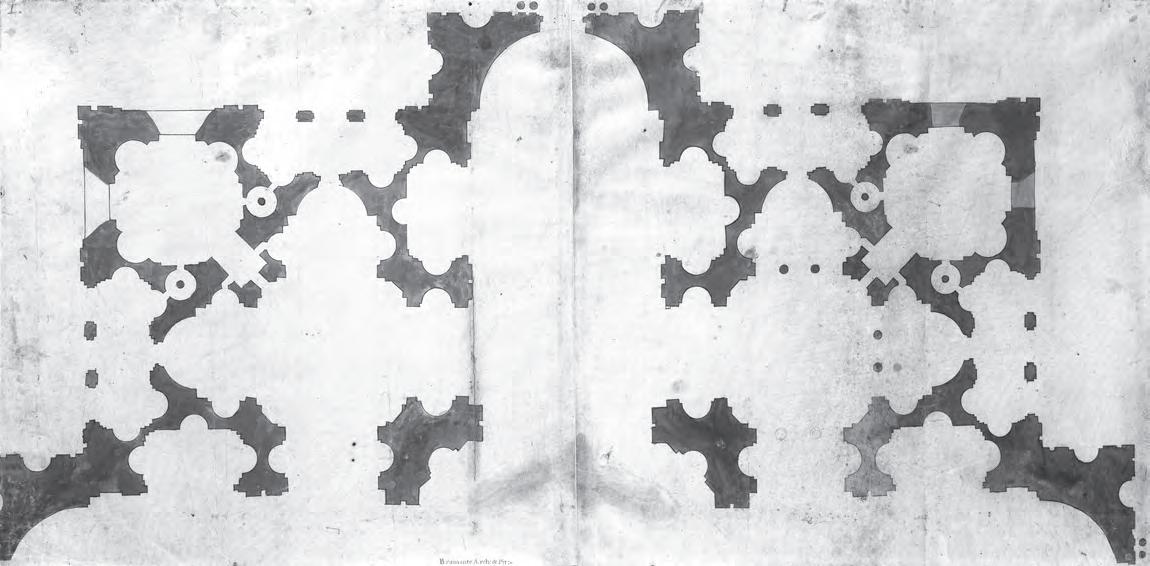

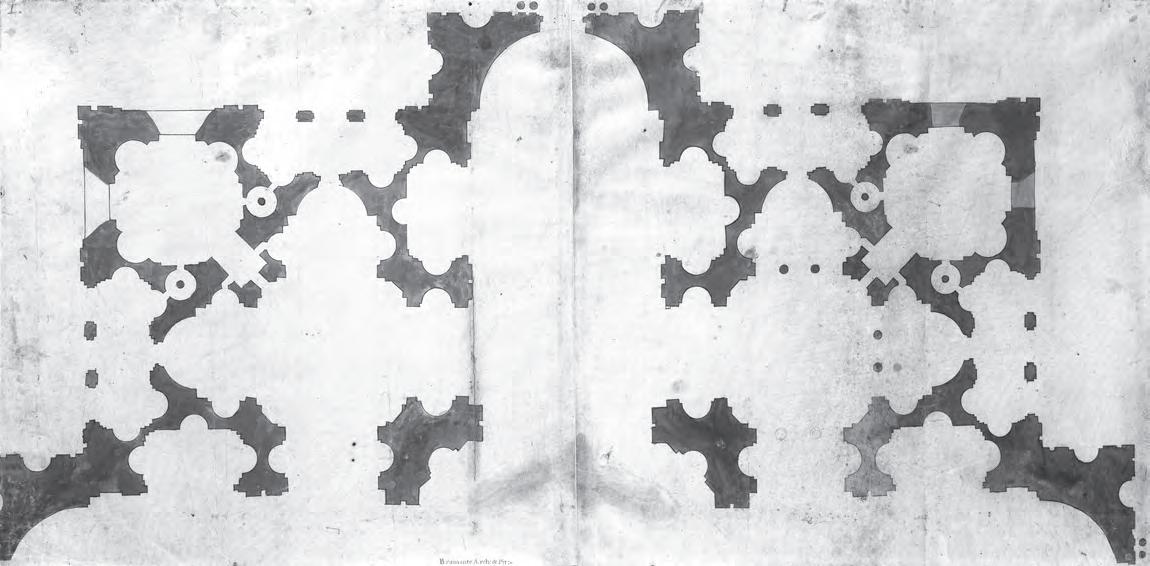

91 Artemisia Gentileschi and Feminism in Early Modern Europe, M.D Garrard by babette bohn

92 A Companion to Late Medieval and Early Modern Siena, S. Casciani and H. Richardson Hayton, eds by giulio dalvit

93 On Bramante, P.P. Tamburelli by david hemsoll

95 Il Mobile a Roma dal Rinascimento al Barocco, A. González-Palacios by simon swynfen jervis

97 La nascita di una collezione: Gli Hercolani di Bologna (1718–1773), B. Ghelfi by linda borean

97 Improbable Pioneers of the Romantic Age: The Lives of John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, and Georgina Gordon, Duchess of Bedford, K. Davidson by richard ormond

99 Mary Gillick: Sculptor and Medallist, P Attwood by mark stocker

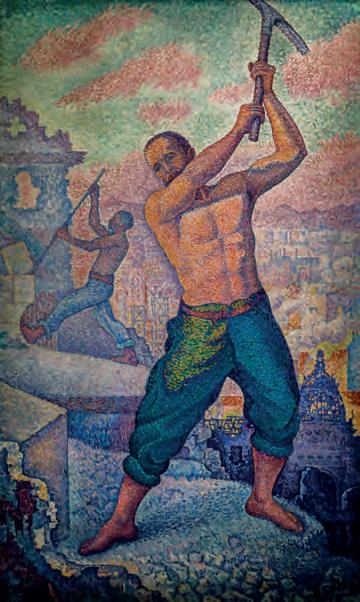

100 Paul Signac: Journal 1894–1909, C. Hellmann, ed. by richard thomson

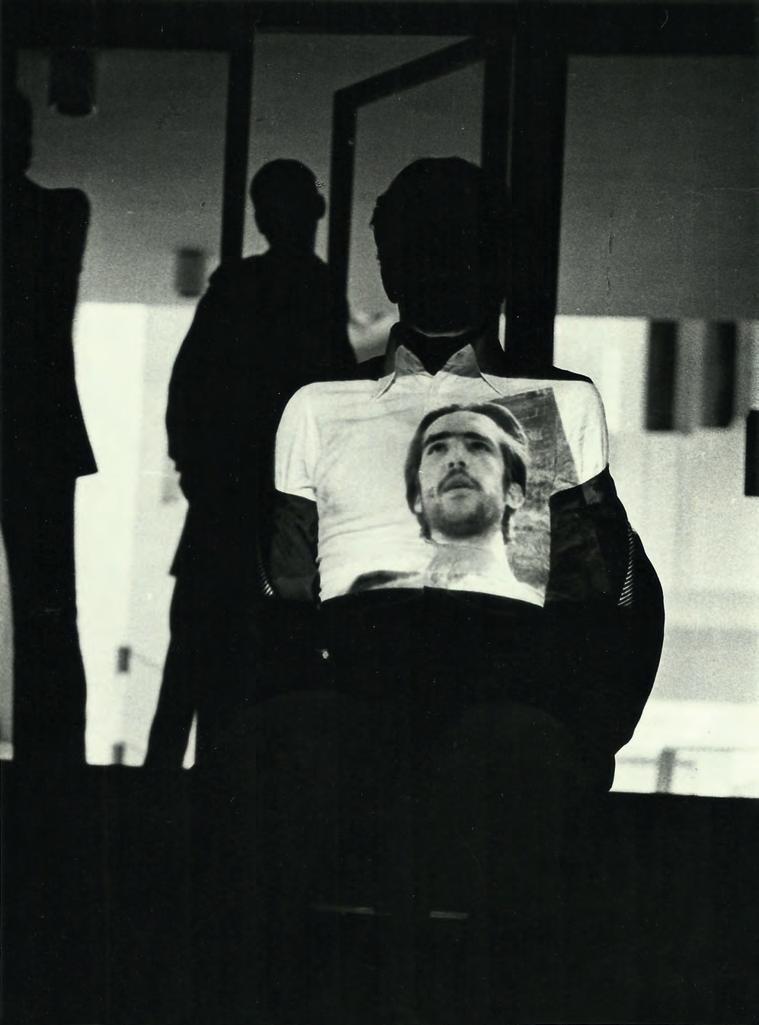

101 Against the Avant-Garde: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Contemporary Art, and Neocapitalism, A.H. Merjian by robert silberman

Obituary

103 Angus Trumble (1964–2022) by andrew hopkins 104 among this month’s contributors

Contents Volume 165 | Number 1438 | January 2023

Editor

Michael Hall Reviews Editor

Alexandra Gajewski

Contemporary Art Editor

Kathryn Lloyd

Assistant Articles Editor

Christine Gardner-Dseagu

Assistant Reviews Editor

Lisa Stein

Editorial Assistant, Burlington Contemporary Yi Ting Lee

Art Editor

Tzortzis Rallis

www.burlington.org.uk www.contemporary.burlington.org.uk

14–16 Duke’s Road, London wc1h 9sz Tel: 020–7388 1228 Email: burlington@burlington.org.uk Editorial Tel: 020–7388 8157

© The Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd

All rights reserved Printed in Wales by Stephens & George, Merthyr Tydfil Print issn 0007 6287 Online issn 2044 9925

Managing Director

Andrew Dunn

Advertising & Development Director Mark Scott

Head of Partnerships Sarah Bolwell

Head of Commercial Design & Production Chris Hall

Marketing & Circulation Manager Hannah Daldry

Marketing & Advertising Executive Nicole Gilchrist-Reeves Office Administrator Serena Sclocco

The Burlington Magazine is owned and published by Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd. Registered in England, company no.790136. Registered charity in England and Wales no.29502. Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd is owned and supported by the Burlington Magazine Foundation CIO (charity no.1187286) and the Burlington Magazine Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit company incorporated in the State of New York, USA.

Directors, BMPL

Caroline Campbell

Craig Clunas fba

Simon Swynfen Jervis fsa Nathanael Price

Andrea Rose cmg obe

Desmond Shawe-Taylor lvo, Chairman Anna Starling Paul Williamson obe fsa frhists

Trustees, BMF CIO Hugo Chapman

Elizabeth Cropper Gabriele Finaldi David Landau cbe

John Nicoll, Chairman Sir Nicholas Penny fba fsa Jane Portal fsa Andrea Rose cmg obe

Desmond Shawe-Taylor lvo Catherine Whistler

the burlington magazine foundation’s benefactors and supporters

Directors, BMF Inc. Andrew Dunn

Colin B. Bailey Joseph Connors

Lynne Cooke

Elizabeth Cropper John Nicoll, Chairman Patricia Rubin John Walsh

Contributing institutions

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth Fondation Custodia, Paris

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The J. Paul Getty Museum Director’s Council Yale Center for British Art, New Haven

Supporters

Charles Booth-Clibborn

Commercial supporters Bridgeman Images John Sandoe Books Ltd

The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF)

Benefactors

The Michael Marks Charitable Trust Timothy Llewellyn obe Richard Mansell-Jones

consultative committee

Past benefactors & supporters

The late Gilbert de Botton

Sir Harry Djanogly cbe • Francis Finlay

Nicholas and Judith Goodison •Daisaku Ikeda

The late Paul Z. Josefowitz • John Lewis obe

The late Jan Mitchell • Mr and Mrs Brian Pilkington Mrs Frank E. Richardson • Sir Paul Ruddock fsa

Nancy Schwartz • Madame Andrée Stassart

The late Saul P. Steinberg • Janet de Botton

Gifford Combs • The late Hester Diamond Mark Fisch • The Lady Heseltine

The Rt. Hon. Lord Rothschild om gbe fba Patricia Wengraf

Dawn Ades cbe fba

David Anfam

Colin B. Bailey

David Bindman

Christopher Brown cbe

Richard Calvocoressi cbe

Lorne Campbell

Lynne Cooke

Caroline Elam

David Franklin

Julian Gardner fsa

Elizabeth Goldring frhists

Christopher Green fba

Tanya Harrod

Simon Swynfen Jervis fsa

C.M. Kauffmann fba

Rose Kerr Felix Krämer

Alastair Laing fsa

Shane McCausland

Elizabeth McGrath fba

Robin Middleton

Jennifer Montagu cbe lvo fba fsa

Peta Motture fsa

Sir Nicholas Penny fba fsa

J.M. Rogers fba fsa Pierre Rosenberg

John-Paul Stonard

Deborah Swallow

Gary Tinterow

Julian Treuherz

Simon Watney

Sir Christopher White cvo fba Paul Williamson obe fsa frhists

Subscription & Advertising Enquiries Telephone: 020–7388 1228 Email: subs@burlington.org.uk Annual Subscription rates for Individual Subscribers (Agencies and Institutional rates published on www.burlington.org.uk) Full digital access: United Kingdom £240 • USA $324 • Canada $324 • EU €276 • Rest of World £240 12 Print issues (including full digital access): United Kingdom £300 • USA $800 • Canada $780 • EU €500 • Rest of World £500 *VAT applied to UK and EU customers. Attributions and descriptions relating to objects advertised in the magazine are the responsibility of the advertisers concerned. © The

Magazine Publications Ltd. All rights reserved.

members of the Consultative Committee give invaluable assistance to the Editor on their respective subjects, they are not responsible for the general conduct of the Magazine.

Burlington

Although the

A spoonful of sugar

Let’s try to be positive. Nobody can pretend that 2022 ended in an entirely rosy fashion for the world’s museums. Still in recovery mode after the pandemic, with visitor numbers in most cases not yet back to pre-2020 levels, and having to cope like everybody else with resurgent inflation and soaring energy costs, they are facing challenges caused on the one side by politcal activism, as Stop Oil protestors have targeted art as way of promoting their environmental message, and on the other by governments seeking to use museums as tools for social engineering. In November, and with no prior warning to the institutions affected, Arts Council England announced cuts designed to reallocate funds to areas of the country that the government has targeted for levelling-up, making a mockery of the idea that it operates at arm’s length from its political masters. To take only the most egregious example, the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, had its annual grant cut by 50 per cent, from £1.21 million to £617,534, putting its educational and outreach programmes at risk. Our annual selection of exhibitions to look forward to in the year ahead is therefore taking a lead from Mary Poppins – bearing in mind that the Walt Disney Company is celebrating its one hundredth anniversary in 2023 – by offering a spoonful of sugar for bitter times.

Nowhere are they more bitter than Ukraine, where to the wholesale destruction of museums in, for example, Lyman and Rubizhne, has been added the looting of the museum in Mariupol by Russian troops. That backdrop makes the success of Ukraine’s cultural authorities and curators in staging the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900–1930s at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid (to 30th April), all the more impressive. Around seventy works, ranging from oil paintings to collages and theatre designs, trace the avant-garde movements in Ukraine led by such artists as Oleksandr Bohomazov, Vasyl Yermilov, Viktor Palmov and Anatol Petrytskyi. An exhibition with particular resonance for violent events unfolding in another part of the world, the protests in Iran that have followed the death in police custody of Mahsa Amini in September 2022, is Women Defining Women In Contemporary Art of the Middle East and Beyond at the Los Angeles County Musuem of Art (23rd April–24th September), which will present seventyfive works by women artists born or living in Islamic societies who seek to challenge stereotypes.

In Paris, memories of the fire that engulfed Notre Dame in April 2019 remain vivid, but the rapid progress made in repair and restoration is heartening. An opportunity to see at close quarters the treasures that were so nearly lost will be provided by The Treasury of Notre Dame Cathedral from its origins to Viollet-Le-Duc, at the Musée du Louvre (19th October 2023–19th February 2024), which will highlight the reliquaries ordered by Napoleon for the Crown of Thorns and a fragment of the True Cross. There is perhaps particular pleasure during times of hardship in looking at objects of luxurious splendour, in which case we can look forward to Luxury and Power: Persia to Greece at the British Museum, London (4th May–13th August), which explores the way luxury was used as a political tool in the Middle East and south-east Europe from 550 to 30 BC. If any exhibition can add cheerfulness to life it will be Beyond Bollywood at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco (31st March–10th July), which celebrates two thousand years of the depiction of dance in the arts of Asia.

There is no shortage of monographic shows this year. Leading the way with the hottest ticket in town is Vermeer at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (10th February–4th June), which promises no fewer than twenty-eight works by the artist. At the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Hugo van der Goes: Between Pain and Bliss, which opens on 31st March (to 16th July), is surprisingly the first-ever exhibition devoted solely to him. Best known for his portrait by Diego Velázquez, the painter Juan de Pareja (c.1608–70) is given his own exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter (3rd April–16th July). Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, is staging Berthe Morisot: Shaping Impressionism, her first major exhibition in the United Kingdom since 1950 (31st March–10th September), and the Accademia Carrara, Bergamo, has an exhibition on that most enigmatic and idiosyncratic of Caravaggio’s followers, his lover Cecco del Caravaggio (26th January–4th June). Giacomo Ceruti: A Compassionate Eye at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (18th July–29th October), focuses on this eighteenth-century artist’s hauntingly realistic depictions of beggars and vagrants. Of all the many contemporary art monographic shows, Mike Nelson: Extinction Beckons at the Hayward Gallery, London (22nd February–7th May), is particularly eagerly anticipated. Nelson’s installations will, we are promised, take us into ‘fictive worlds that eerily echo our own’.

It is not a classic year for artists’ anniversaries – the three-hundredth anniversary of Joshua Reynolds’s birth would pass largely without notice were it not for an exhibition at The Box in his native Plymouth, Revisiting Reynolds: A Celebration (24th June–29th October). The biggest name to receive anniversary attention is Picasso, who died fifty years ago, on 8th April 1973. An astonishing forty exhibitions are said to be in preparation, conveniently listed on the website of the Picasso Museum, Paris.1 The one that seems likely to provoke the widest interest will be at the Brooklyn Museum (2nd June–24th September), still untitled at the time of writing, which promises to examine the issues of misogyny, masculinity, creativity and ‘genius’ that surround the artist’s reputation.

It would be an interesting debate whether Picasso or Disney can claim to have had the bigger impact on global visual culture. A visitor to one of the Picasso exhibitions can ponder the question at Disney 100: The Exhibition, which opens at the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, on 18th February and will be seen also in Munich and London.2 It is now ninety years since the critic Dorothy Grafly, in a famous review of the art of Walt Disney, declared that ‘He goes to nature for his material, but it is the nature of the poet. Quite as much as Picasso he distorts and renders unreal, but from this unreality one derives a fine emotional participation that brings conviction’.3 Perhaps the comparison is not so absurd: Dalí’s and Mondrian’s admiration for Disney is well known, and anyone who doubted the artistry of his cartoons had the opportunity to be persuaded by the exhibition Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts, seen in 2021–22 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Wallace Collection, London.4 In any case many museum directors and curators are probably hoping that 2023 will bring more than the bare necessities.

1 www.museepicassoparis.fr/en/celebration-picasso-1973-2023, accessed 19th December 2022.

2 For full details, see www.disney100exhibit.com/en/, accessed 19th December 2022.

3 D. Grafly: ‘America’s youngest art’, The American Magazine of Art 26 (1933), pp.336–42, at p.342.

4 Reviewed by Kee Il Choi Jr in this Magazine, 164 (2022), pp.504–07.

the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023

3

Editorial

focus on bronzino

Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour re-examined

Technical analysis by the Art Gallery of New South Wales of its portrait by Bronzino of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour has revealed more details of the mysterious underlying portrait first observed in a X-radiograph in the 1980s. It has also established that Bronzino hesitated between making the portrait half-length or three-quarter-length, confirming that the painting is the prime autograph version of the three-quarter-length image.

by paula dredge, anne gérard-austin, daryl howard and simon ives

Agnolo di cosimo, known as Bronzino (1503–72), was the leading painter in mid-sixteenth-century Florence, where he served as court painter to Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–74). His portraits are characterised by an intense concentration and an almost unnerving clarity – none more so than the version of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (Fig.1). In this magnificent likeness of the duke, Bronzino displays a perfectionism characteristic of his artistic style. If the duke’s diverted gaze reveals a sense of anxiety in the stillyouthful ruler, his steely reserve is cleverly accentuated by his forbidding armour. Rendered with reflections, highlights and shadows, and lined with rich red velvet, Cosimo’s armour is an article of transfixing interest.

The portrait was commissioned by the duke as a gift for the gallery of illustrious men formed by Paolo Giovio (1483–1552) on Lake Como.1 Giovio was a Lombard historian, physician and prelate who in the last years of his life became a friend and adviser of Cosimo.2 A letter from Giovio to Cosimo’s majordomo, Pier Francesco Riccio (1501–64),3 dated 30th July 1546, thanks the duke for ‘the marvellous portrait of His Excellency [which] was so pleasing to the gentlemen of this [Papal] Court, and judged excellent by painters [. . .] blessed be the hand of Bronzino, which I think surpasses that of his teacher Pontormo’.4

The identification of the panel as the work commissioned for Giovio is supported by the presence of the Latin inscription ‘cosmvs/ medices

1 The portrait is recorded in the catalogue of Paolo Giovio’s collection in P. Giovio: Elogia vivorum bellica virtute illustrium, Basel 1551, Book 7, pp.338–

39. The gallery, known as the ‘Museo’, was established near the site of the villa of Pliny the Elder at Borgo Vico on Lake Como.

2 The primary source on Giovio in English is the comprehensive biography by T.C. Price Zimmerman: Paolo Giovio: the Historian and the Crisis of Sixteenth-century Italy, Princeton 1995.

3 On Pier Francesco Riccio, see A. Cecchi: ‘Il maggiordomo ducale Pierfrancesco Riccio e gli artisti della corte medicea’, Mitteilungen des

Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz 42 (1998), pp.115–43.

4 ‘Signor mio honorando, il mirabile ritratto di Sua Excellenza è piacciuto summamente alli galanthuomini di questa Corte, et giudicato finissimo da’ pittori [. . .] et benedatta sia la mano di Bronzino qual mi pare che avanzi quella del Pontorni [sic] suo maestro’, Archivio Stato di Firenze (hereafter cited as ASF), Mediceo del Principato, vol.1170a, fol.104r, letter from Paolo Giovio to Pier Francesco Riccio, 30th July 1546.

5 See R.B. Simon: ‘Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I in armour’, THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE 125 (1983), pp.527–39, at

the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023 4

1. Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour, by Agnolo Bronzino. c.1545. Oil on poplar panel, 86 by 66.8 cm. (Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Diana Panuccio).

• dvx/ flor’ (‘Cosimo de Medici, duke of [the] Floren[tine Republic]’) in the lower-right corner of the painting. Unique among the many versions of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour, this inscription is a formula used on other portraits of famous personages owned by Giovio. Although difficult to see, the presence at lower right of the Medici broncone – a laurel tree stump with a vigorous leafy side shoot on which the sitter’s helmet rests – is also associated with Giovio, who had promoted the use of the iconographic device to represent and legitimate Cosimo’s leadership of Florence.5 Cosimo belonged to a secondary branch of the Medici family and succeeded to the dukedom in 1537 only when the main Medici line was extinguished by the assassination of Alessandro de’ Medici (1510–37). The broncone suggested that Cosimo was a true heir of the Medici patriarchy and represented an alternative, but forceful, new growth from the family tree.

Although Giovio’s collection had largely been dispersed by the end of the sixteenth century, the Sydney portrait remained in the Giovio family until 1860.6 It was then sold to Napoléon-Jérôme Bonaparte, Prince Napoléon (1822–91) and cousin of Emperor Napoléon III, better known by his popular nickname ‘Plon-Plon’. Following the sale of his collection in 1872, the painting was acquired by the celebrated collector Alfred Morrison of Fonthill, Wiltshire (1821–97).7 Having subsequently passed

p.533. This side shoot is almost impossible to see in the painting today but is clearly imaged by technical examination, as discussed later in the present article.

6 In the late sixteenth century the painting was transferred with the rest of the ‘Museo’ collection to Palazzo Giovio, Como. On Giovio’s Gallery, see L.S. Klinger: ‘The portrait collection of Paolo Giovio’, unpublished PhD diss. (Princeton University 1991); and P. Giovio: Ritratti degli uomini illustri, ND, ed. C. Caruso, Palermo 1999.

7 See Sale, Christie’s, London, Works of Art from the Collections of his Imperial Highness the Prince Napoleon

[. . .], 10th May 1872. According to a handwritten note on p.26 of a copy of the sale catalogue in the National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1030527571, it was sold to ‘Holloway’ for £341 5s. This was the art dealer Thomas Holloway & Sons, who, at least from 1864 and 1870, operated at Bedford Street, Covent Garden, London. Holloway acted as an agent for Alfred Morrison, to whom the painting was most likely sold soon after the May 1872 auction. The painting remained in the Morrison family until it was sold in 1971; see Sale, Christie’s, London, Important Pictures by Old Masters, 26th November 1971, lot 47.

the

magazine | 165 | january 2023 5

burlington

through a private collection in London, the painting was purchased by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1996.8

While the painting was in London it was studied by the art historian Robert Simon, who published two articles on it in The Burlington Magazine, in 1983 and 1987. He established the unbroken provenance of the painting back to the sixteenth century, argued that it was an autograph work by Bronzino, and proposed that it was the archetype of the three-quarter-length version of the often-replicated composition of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour.9 The 1987 article also published an

8 For the complete provenance, see www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/ works/78.1996/, accessed 23rd November 2022.

9 Simon, op. cit. (note 5); and idem: ‘Blessed by the hand of Bronzino; the portrait of Cosimo I in armour’, THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE 129 (1987), pp.387–88.

10 Ibid., p.387, fig.44.

11 Simon, op. cit. (note 5), pp.536–39, ‘Appendix II. Check list of known versions of Bronzino’s portraits of Cosimo I in armour’.

12 Inv. no.MNP M05. Oil on panel, 74.5 by 58 cm.

13 Inv. no.08.262. Oil on panel, 95.9 by 70.5 cm.

14 See C. Falciani and A. Natali, eds: exh. cat. Bronzino: Artist and Poet at the Court of the Medici, Florence (Palazzo Strozzi) 2010, p.114. For a discussion of the irregular appearance of the Golden Fleece insignia on Cosimo portraits and its use for dating the panels, see Simon, op. cit. (note 5), p.531 and p.531, note 13.

15 Simon, op. cit. (note 5), p.531.

16 The panel maker was likely the sculptor, carver and architect Giovanni Battista del Tasso (1500–55), who made for Cosimo the carved limewood ceiling of the Laurentine Library, Florence, in 1549. Tasso is also mentioned as the panel maker for the large Lamentation over the dead Christ commissioned by Cosimo for the chapel of Eleonora di Toledo in the Palazzo Vecchio, see ASF, Mediceo del Principato, vol.1170a, fol.36r, letter from Bronzino to Pier Francesco Riccio, 22nd August 1545.

17 See S. Heffney: ‘Bronzino: master of mystery’, American Institute for Conservation Preprint Abstracts, Buffalo NY 1992, p.17. Heffney observed that microscopic examination of paint cross sections taken from Bronzino’s Portrait of a young man (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City) showed the presence of a glue layer polished into the gesso ground. He suggested that this assisted in creating the smooth finish of the artist’s paintings but also rendered them vulnerable to paint lifting and flaking. He postulated that a similar history of paint

2. Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour, by Agnolo Bronzino. 1543. Oil on panel, 71 by 57 cm. (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence; Bridgeman Images).

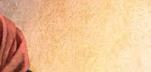

X-radiograph image of the painting, which revealed that the panel had an obscured portrait underneath the figure of Cosimo.10 Simon suggested that the hidden painting may be an earlier portrait of the duke. Recent technical examination undertaken by the Art Gallery of New South Wales using technologies developed since the 1980s, such as high-resolution X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) elemental mapping, has revealed greater details of both the upper and lower portraits on the panel and thrown new light on the development of this extended version of the celebrated composition. It also raises new hypotheses regarding the subject of the lower painting and identifies some potentially related portraits within Bronzino’s œuvre.

In a check-list of the versions of the portrait published in his 1983 article,11 Simon identified the primary, autograph version as being that in the Tribuna of the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, which, according to Giorgio Vasari, was painted in 1543 (Fig.2). It was likely followed by the version painted c.1545 that is now in the Muzeum Narodowe, Poznań.12 Shortly after these two half-length portraits were painted, an awkwardly conceived and extended three-quarter-length version (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) was attempted by Bronzino’s workshop.13 Bronzino must have completed the Sydney panel by 29th July 1545, as Cosimo is not shown wearing the insignia of the Golden Fleece, bestowed on him by Charles V, which arrived in Florence on that date and was included in subsequent portraits of the duke.14 Simon judged that of all these portraits the Sydney three-quarter-length version is ‘unquestionably the finest of the large format pictures both in its execution and its formal structure’.15 At least twenty-five versions of the Cosimo portrait are known to exist, many of which are variations on this extended length version. They include autograph and workshop versions, as well as later replicas by other hands.

The Sydney version of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour is remarkably well preserved, having retained the full width of its thick poplar panel without later thinning or cradling. The panel comprises three vertical planks, butt-joined with no pegs or dowels imaged by X-radiography.16 The panel suffered a complete break through the centre at an unknown date. This was repaired with a slight misalignment of the surface plane along the join with two horizontal batons nailed across the break at

separation on other paintings might be evidence of Bronzino’s workshop practice.

18 Inv. no.NG651. See C. Plazzotta and L. Keith: ‘Bronzino’s “Allegory”: new evidence of the artist’s revisions’, THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE 141 (1999), pp.89–99.

19 Inv. no.1950-86-1. See M.S. Tucker: ‘Discoveries made during the treatment of Bronzino’s “Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus”’, Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 81, no.348 (1985), pp.28–32.

20 See J. Cox-Rearick and M. Westerman Bulgarella: ‘Public and private portraits of Cosimo de’ Medici and Eleonora di Toledo: Bronzino’s paintings of his ducal patrons in Ottawa and Turin’, Artibus et Historiae 25, no.49 (2004), pp.101–59.

21 Musée des beaux-arts et d’archéologie, Besançon, inv. no.D.799.1.29.

22 ‘io la vogl[i]o in quel modo proprio come sta quella et non la vogl[i]o più bella, quasi dicesse non m’entrare in altra invention perché quella mi piace’,

ASF, Mediceo del Principato, vol.1170a, fol.36r, letter from Bronzino to Pier Francesco Riccio, 22nd August 1545.

23 ‘Ieri, che fumo alli XXI del presente, fui con S[ua] E[ccellenza] [Cosimo I] per cagione del Ritratto, dove dissi quanto per vostra s[ignoria] [Riccio] mi fu imposto circa la speditione della Tavola per in Fiandra, et come volendo sua E[ccelenza] che se ne rifacessi un’altra, bisognava stare costì alma[n]co otto o dieci giorni per farne un poco di disegno’, ibid

24 Simon, op. cit. (note 5), p.531.

25 Ibid., p.532, note 19. The Uffizi panel is 71 by 57 cm. and the area within the inscribed lines on the Sydney panel is only slightly larger at 75.6 by 61.7 cm.

26 See C. Gamba: ‘Il ritratto di Cosimo I del Bronzino’, Bollettino d’arte 5 (1925), pp.145–47, cited in Simon op. cit. (note 5), p.531, note 16, as supporting ‘the primacy of the half-length format by maintaining that the three-quarter length versions are later expansions of the original image, executed several years after it and probably by followers of the artist’.

Focus on Bronzino the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023 6

the back. A line of subsequent filling and retouching down this join also exists, visible in the X-radiograph and other technical images as an anomaly with the original paint. Furthermore, there is a history of paint lifting and tiny losses across the painting that is consistent with published findings on other paintings by Bronzino, and which may relate to the methods he used to achieve his incredibly smooth surfaces.17 The painting was restored in the 1980s by the London-based painting conservator Herbert Lank. The treatment consisted of surface repairs only – the removal of an old varnish and previous restorations as well as minor retouching and the application of a new varnish.

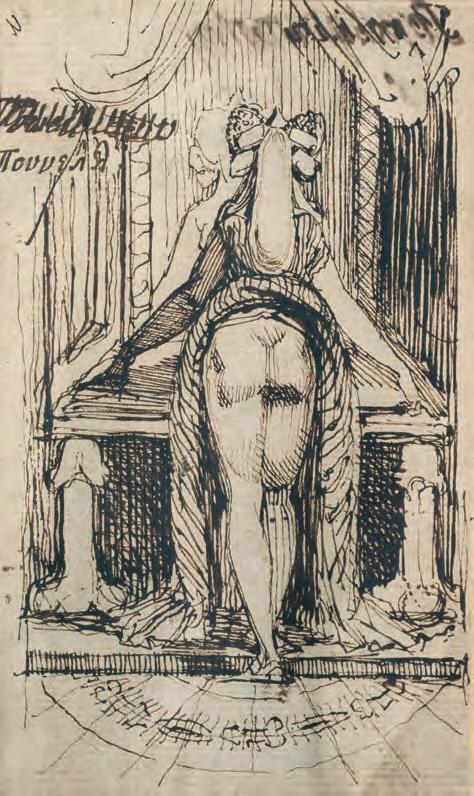

Other paintings by Bronzino that have been studied using X-radiography and infra-red examination provide valuable insights into the artist’s working methodology in general and the evolution of the Sydney panel in particular. For instance, Allegory with Venus and Cupid (c.1545; National Gallery, London) is a complex arrangement of figures that Bronzino modified several times during its development, including altering Cupid’s initial frontal pose to a back view, the original knees of the figure being cleverly reworked as buttocks.18 In the celebrated Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus (c.1537–39; Philadelphia Museum of Art) the main figure was initially partially clothed in animal fur before being reworked into full nudity.19 These pentimenti – unusually extensive but not without precedent in Bronzino’s creative process – are hidden by the smooth final renderings of his paintings. The appearance of control, planning and elegant ease of process belie the complex compositional changes revealed through technical analysis.

In contrast to these primary compositions displaying evidence of pentimenti are the replicas of Bronzino’s paintings that he and his workshop were required to make occasionally for distribution to Cosimo’s political patrons.20 In the summer of 1545, for instance, Bronzino painted a large altarpiece, the Lamentation over the dead Christ, for the private chapel of Cosimo’s wife, Eleonora di Toledo, in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence.21 Once it was completed, however, Cosimo decided to send the altarpiece to Nicolas Perrenot de Granvelle (1486–1550) in Besançon as a diplomatic gift (Granvelle was one of the most trusted advisers of the Emperor Charles V) and requested Bronzino to make a replica for his wife’s chapel. In a letter to Riccio, Bronzino records Cosimo saying to him: ‘I want it exactly as the other and I do not want it more beautiful’.22 That the duke felt the necessity to emphasise his desire for an exact copy suggests that he knew Bronzino’s working processes and compulsive predilection for altering compositions. Further insight into Bronzino’s technique for making replicas of his paintings is revealed in a

note from him to Riccio that it was necessary to make a ‘poco di disegno’ of the Deposition of Christ prior to its dispatch, and this would require eight to ten days.23 This ‘small drawing’ of the two-and-a-half-metrehigh panel was likely to have been a full-scale detailed cartoon used to trace the design directly onto another panel of the same size, which remains in the chapel.

The presence of pentimenti indicates that a painting is a primary composition rather than a copy, which would be made in Bronzino’s studio with the use of a detailed cartoon . Simon observed a visible pentimento in the Uffizi painting, leading him to consider it to be the primary version of the Cosimo de’ Medici in armour prototype 24 Two notable errors in the Sydney painting compared to the Uffizi composition are indicative that the former, at least in the central part, is a replica. The top part of the helmet above the right hand is missing and instead the intended outline is just faintly visible as a curved line, which probably formed part of the transferred drawing from the cartoon that was otherwise hidden after the application of the paint layers (Fig.3). In addition, several rivets on the right forearm vambrace in the Uffizi version have been replaced by a decorative pattern. Notwithstanding these transfer errors, the sheer quality of the execution and such touches as a dab of a finger into the wet red lake pigment around the proper left rondel, breaking up the brushstroke to create a skilful play of reflected light, suggest the virtuosity of the master (Fig.4).

How the extended three-quarter-length composition of the Sydney painting might have evolved from the half-length version has been a matter of much conjecture. Embedded horizontal and vertical lines slightly inside the Sydney panel’s edges are still visible on the painting. Simon suggested that these lines were incised in the gesso and indicated the placement of a cartoon taken from the Uffizi painting. 25 This proposition raised questions regarding the extended compositional elements. Was the whole extended composition conceived and painted as one, including the inscription and broncone, with the commission for a painting for Giovio in mind? Or were the compositional extensions added after a half-length replica was already in place in the panel?26

3. Macro photograph of Fig.1, showing a copying error in which the top edge of the helmet has been drawn (placement indicated with white arrows) but mistakenly painted as background. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Diana Panuccio).

4. Macro photograph of Fig.1, showing the reflection of the red ribbon on the proper left rondel. The ridges of red lake paint suggest they were dabbed, leaving the impression of a fingerprint in the paint. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Diana Panuccio).

the

magazine | 165 | january 2023 7

Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour

burlington

The 1987 X-radiograph of the painting revealed not a pentimento as such but another portrait underneath the figure of Cosimo in armour. The sitter in this painting wears a cloak and a soft cap and holds an open book. Simon identified two hidden facial contours, ‘one on either side of the visible profile’ of the lower painting, representing ‘at least one other face’ – most likely two different conceptions of a single abandoned portrait.27 The revealed face(s) could represent a younger Cosimo ‘in mufti’, in Simon’s words, as the facial features seem quite close to the duke’s, or they could belong to a completely different subject.28 If the upper and lower paintings are both portraits of the duke, this too might provide new clues to the evolution of the painting and throw light on the development

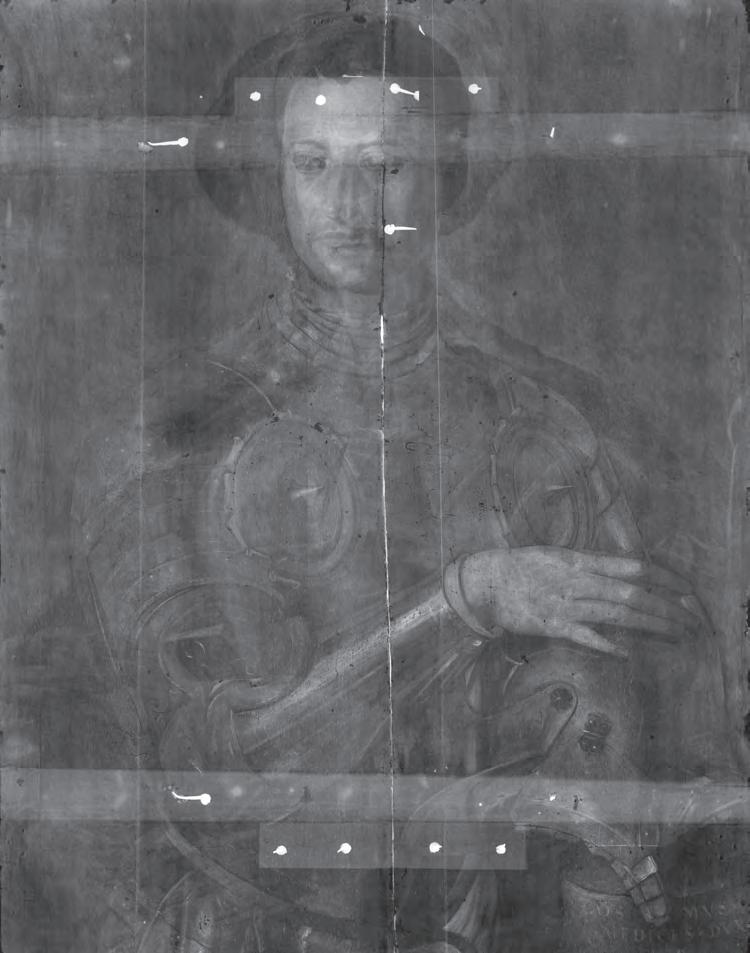

5. Digital X-radiograph of Fig.1. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Paula Dredge).

6. Detail of infra-red reflectogram of Fig.1. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Paula Dredge).

7. Infra-red reflectogram of Fig.1 with placement of incised lines indicated with white arrows. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Paula Dredge).

of this iconic depiction of Cosimo. If the lower portrait is a distinct work, it would raise further questions as to the sitter’s identity and its date, and assist in understanding why it was abandoned.

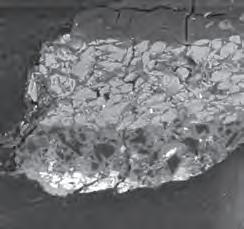

Seeking clarification of these questions, a new technical investigation of the painting was undertaken using the digital technologies of X-radiography and infra-red reflectography (IRR) alongside synchrotronsourced XRF mapping. Microscopic-sized samples of the paint layers were also examined with scanning electron microscopy and analysed with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) to assist in establishing the sequential build-up of the layers of paint. 29 X-radiography locates the distribution of pigments of higher-mass elements, such as lead found in the dominant white pigment used in European painting prior to the twentieth century. The new digital X-radiograph of the Sydney panel is of greater clarity than the previously published image (Fig.5).30 It shows a broad brimmed cap and expansive shoulder line, as well as lips, eyes and neck offset lower and to the right of Cosimo’s face, while the pages of a small book are visible at the bottom left of the panel. Due to the transmission technique of traditional X-radiography, the batons and

the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023 8

Focus on Bronzino

structure of the panel are also strongly imaged, interfering and confusing the image of the paint layers. The difficulty in clearly imaging the lower portrait is also due to the lack of X-ray opaque lead white pigment in the hidden subject’s black cloak and cap.31

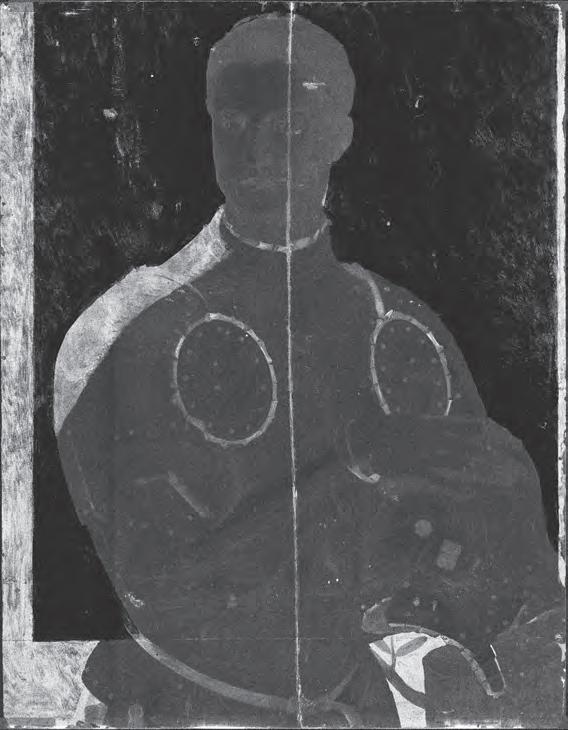

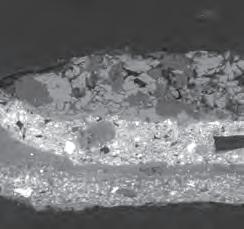

In contrast, infra-red light is typically responsive to black pigments and should penetrate to the lower figure, but the armour of the upper figure is also strongly responsive as a result of carbon black being used to create the silver-grey of the steel.32 The infra-red image gives just a faint indication of a book and the face beneath, particularly the shape and outline of the lower figure’s eyes and facial contours (Fig.6). What is shown more clearly in the IRR than the X-radiograph is an anomaly between the paint of the green background inside and outside of the incised lines (Fig.7).

Because of the continuing lack of clarity of the lower painting in the recent X-radiograph and IRR images, the painting was taken to a particle accelerator for XRF mapping.33 The X-ray Fluorescence

27 Simon 1987, op. cit. (note 9), p.388.

28 Ibid

29 This research was undertaken on the XFM beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, Melbourne, part of ANSTO. Scanning Electron Microscope study was undertaken by Will Lawler at ATA Scientific Pty Ltd.

30 Six digital X-radiograph images were collected at 40 kV, 6mA, 30 sec and stitched together using Photoshop image processing.

31 Carbon-based paint is not imaged with X-radiography due to the low molecular weight of the element. In fact, greater X-ray penetration is visible in the black paint areas of the

lower figure, giving a negative outline of the hat and shoulders.

32 An infra-red reflectogram was collected on Osiris Infra-red Camera (Opus) with an indium gallium arsenide line array sensor and operational wavelength 900-1700nm with a cutout filter 760-860nm and mechanical in camera stitching of sixty-four digital tiles, of 16 megapixels each.

33 The painting was analysed at the Australian Synchrotron on 29th–31th August 2019. Pixel size was 150 microns and scan velocity was 60 mm/s, yielding a pixel dwell time of 2.5 msec. The painting was scanned at two different incident energies, 12600 eV

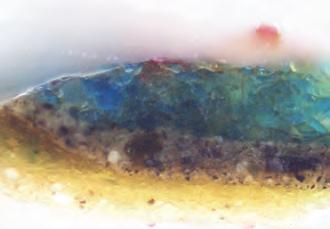

8.

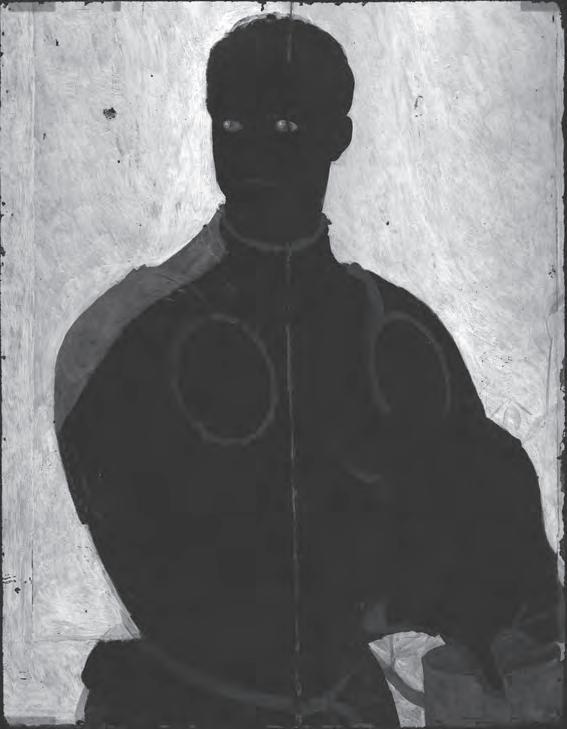

9. XRF scan

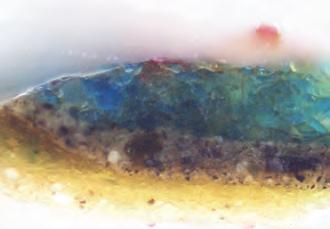

Microscopy beamline at the Australian Synchrotron in Melbourne utilises a fast throughput Maia detector alongside a fine-focused X-ray beam, thus enabling elemental imaging of paintings without visual interference from the panel structure. Importantly, all of the elements present in pigments, from silicon (atomic number 14) to bismuth (83), can potentially be imaged with this technique. The elemental imaging of the Bronzino panel included mercury (present in the red pigment vermilion), copper (related to the use of green pigment), tin (correlated with the use of lead tin yellow), iron (present in a range of ochres) and manganese (specific to the use of umber), as well as the trace elements present in these pigments derived from mineral deposits.

and 18500 eV. The 12600 eV energy is below the lead L3 edge (13035 eV), thus avoiding high-intensity lead fluorescence and potentially providing better sensitivity to lighter elements present in the paint pigments. The 18500 eV energy excites lead, thus giving access to this important element in the painting and allows observation of the trace elements strontium and bismuth. The scanning apparatus has a maximum width of approximately 60 cm. Thus the painting width of 66.8 cm. was too long to scan in one pass, but the 86 cm. height of the painting was within scanning limits of approximately 110 cm. Therefore, two scans were

required to investigate the entire surface of the painting. Images were stitched in the FIJI (ImageJ) software using Plugins – Stitching –Pairwise Stitching. The primary artefact after stitching was the carbon fibre holder at the top and bottom, which in some images appears partially faded out. Over the two-day experiment, the painting travelled a total distance of 8 km back and forth on the scanning apparatus. For further details, see D.L. Howard et al.: ‘The XFM beamline at the Australian Synchrotron’, Journal of Synchrotron Radiation 27 (2020), pp.1447–58.

the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023 9

Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour

XRF scan mapping the distribution of lead in Fig.1. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales).

mapping the distribution of mercury in Fig.1. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales).

the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023 10

Focus on Bronzino

Opposite, clockwise from top left

10. Detail of the XRF copper map of Fig.1, showing an inscribed horizontal line on the lower-right side passing through the broncone and the additional leaves of the side branch. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales).

11. Detail of the XRF lead map of Fig.1, showing an inscribed horizontal line on the lower-right side passing through the broncone and the additional leaves of the side branch. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales).

12. XRF scan mapping the distribution of arsenic in Fig.1. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales).

13. XRF scan mapping the distribution of copper in Fig.1. The black and white arrows indicate the green copper-based azurite pigment embedded into the indentation left in the surface after inscribing lines and the painting out of armour at the waist in preparation for cutting the panel. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales).

14. Detail of Fig.8, showing an inscribed horizontal line on the lower-left side with removal of lead. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales).

The elemental distributions were mapped across the painting, with single greyscale images representing individual elements. For each image, the variable concentrations throughout the painting are indicated by tonal differences: the brighter areas correspond to a higher concentration of the specific element and its associated pigment. Each pixel of the digital image is the XRF spectral result from an area of 150 microns in diameter on the painting (the size of the incident beam on contact with the surface). The maps are accumulated from the analytical results of adjacent areas across the entire surface giving a sharp definition to the fine application of painted details and the brushwork on the painting.

The XRF map from the fluorescence of the element lead resembles a traditional X-radiograph, imaging the use of lead white pigment unimpeded by the visual disturbance of the panel and baton additions at the back (Fig.8). The XRF mercury map indicates the use of vermilion pigment in the opaque bright red colour used for the flesh tone and the warm reflections of the armour as well as its velvet lining (Fig.9). The consistency of the paint and brushwork of the armour across the horizontally inscribed line – seen in both lead and mercury maps –indicates that the three-quarter-length composition was conceived and executed simultaneously. Both maps further demonstrate that the lower horizontal line is not a preparatory guide for the placement of a cartoon in the gesso as Simon suggested, but is instead the result of paint from the armour being removed afterwards (Fig.14). However, the sharp and fine incision lines must most likely have occurred in the artist’s studio before the paint had fully dried and become brittle. The broncone was also painted during this same stage of painting. The XRF copper and lead maps show the laurel shoot emerging from the left side of the stump underneath the helmet with four leaves and continuing vertically upwards (Figs.10 and 11). The two larger leaves beneath the helmet were also scratched by the inscribed horizontal line visibly in both maps, confirming their early presence in the composition.

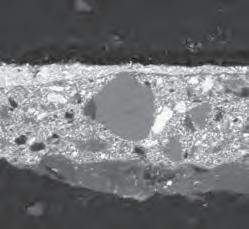

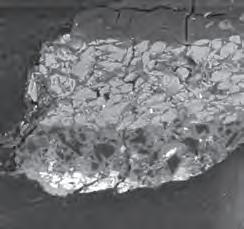

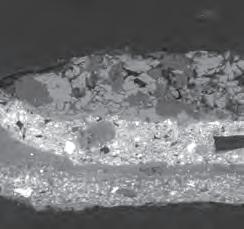

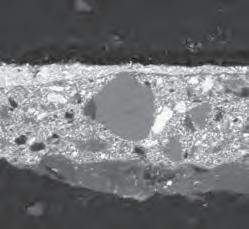

In contrast, the background appears to have been painted in two separate stages, inside and outside the inscribed lines (as previously indicated by the infra-red image; see Fig.7). The copper map identifying the copper-based azurite pigment used for the green curtain background shows a discontinuity of the brushstrokes across the lines (Fig.13). Furthermore, a difference in the concentration of the trace element arsenic inside and outside the lines is also apparent in the XRF arsenic map (Fig.12). Because of this anomaly, micro-samples of paint were taken from

34 Scanning electron microscope and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis was undertaken with a G5 Phenom ProX.

35 A technical study of historic azurite pigment has demonstrated a variety in the trace elements typically present, which included arsenic in the

the edges of pre-existing paint losses, set in polyester resin and polished back to reveal the layers of the painting (Figs.15–17). The cross sections obtained show that the portrait’s dark green background comprises a rich deep green azurite alongside a little lead white layered with a red lake glaze to create the shadows of the curtain. A large green azurite crystal in the cross section taken from the background outside the inscribed line was analysed with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis (see Fig.15).34 It revealed that there were two distinct elemental phases on the azurite crystals from this area – one containing copper and the other arsenic (as well as calcium and magnesium). Conversely, a similar sample taken from inside the inscribed line showed the azurite pigment particles did not contain an arsenic phase (see Fig.16). This result indicates that there were at least two chemically distinct batches of azurite in use in Bronzino’s studio.35

The best fit for the differences observed in the technical images and XRF maps is that after completing the expanded three-quarter-length figure but prior to painting the green curtain background, the decision was made to reduce the painting back to the half-length format of the Uffizi version. The vertical and horizontal lines were inscribed into the still-pliable paint to indicate the reduced size. Prior to cutting the panel, the azurite background was applied around Cosimo up to the inside edges of the inscribed lines and across a small section of armour below his waist at the lower left, which was no longer required in the reduced format (see Fig.13 with the area of azurite paint over the armour at the waist indicated with arrows).

Italian and Dutch samples but not the French. See L. Smieska, R. Mullett, L. Ferri and A. Woll: ‘Trace elements in natural azurite pigments found in

illuminated manuscripts investigated by synchrotron X-ray fluorescence and diffraction mapping’, Applied Physics A 123, no.7 (June 2017), article no.484.

the

11

Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour

burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023

For undiscovered reasons, however, the plan to cut the panel and reduce the composition back to the half-length format was not carried out. The green background was therefore continued beyond the incised area to the edges of the panel, this time using the batch of azurite containing trace amounts of arsenic. The small patch of armour at the lower-left waist was reinstated (Fig.18). The background surrounding the part of the broncone, which is underneath the helmet, was also repainted and two small leaves were painted over, leaving in place only the two larger leaves. These minor modi cations revealed by analytical examination can therefore be regarded as true pentimenti on the Sydney version of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour. The three-quarter-length composition, although originally painted in full on the large panel, was extensively modi ed during deliberations whether to reduce it to the half-length format, however, ultimately the decision was to retain the larger format.36 Once completed in its original large format, the portrait was sent to Paolo Giovio, who received it enthusiastically.

The various issues relating to the modi cations of the composition are partially the result of the panel having originally been used for a di erent painting, as revealed in the X-ray, IRR and XRF images. The striking composite image of the two elemental maps of iron and mercury, overlaid and colour-ta ed, gives the best picture of the lower painting, despite being partly obscured by the presence of the overlying portrait (Fig.19). By examining each elemental map in turn and tracing the features that are not visible in the nished painting onto a single image, it is possible further to clarify the underlying work (Fig.20).

The image demonstrates Bronzino’s organic approach to composition, dynamically evolving and revising his subject on the panel. The most dramatic feature appears in the mercury map showing the artist’s use

of the bright red vermilion pigment (see Fig.9). It provides us with a remarkable image of at least three new hands. This accords well with the hypothesis that we are seeing two di erent conceptions of a single abandoned portrait.37 The fact that the hands appear in the mercury map but only faintly in the lead map shows that they were initial thoughts, thinly sketched in vermilion alone and not yet worked up in pale esh tones with the addition of lead white. The sitter’s left hand can be seen clearly in two di erent positions. The upper attempted hand is strongly drawn, with the index nger extended and holding an open book. The second left hand appears lower down with all ngers extended, possibly resting upon a supporting edge. The sitter’s right hand can be distinctly seen in the lower-left corner, loosely sketched but clearly formed, close to and level with the lower left hand. The

Left, top to bottom

15–17. Paint cross sections and SEM backscattered electron images of the painting illustrated in Fig.1. Locations of sample sites are indicated by the white letters in Fig.18.

15. Paint cross section outside the inscribed line showing two phases of blue/green azurite crystals, one circled in white.

16. Paint cross section of the green background inside the inscribed area showing a single phase of azurite crystals.

17. Paint cross section on the shoulder showing a thin layer of leadbased paint from armour with grey/green background from the l ower painting and a two-phase azurite pigment circled in white. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Paula Dredge).

18. Purple indicates the areas of copper-based azurite background containing arsenic (outside the inscribed line and upper shoulder). Red indicates the area of copper-based azurite background that does not contain arsenic. Green indicates the area of copper-based azurite background not containing arsenic but repainted. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Paula Dredge).

Focus

THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE | 165 | JANUARY 2023 12

on Bronzino

a b c a c b

index finger and thumb are extended, perhaps resting on or holding an unknown object. A second right hand may also be visible in an upper position but the overlap with the folds of the sleeve at the elbow makes it difficult to interpret.

Both copper and arsenic maps indicate that there was a background in place for the lower painting before being hidden by the deep green curtain of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour (see Figs.12 and 13). This first background is imaged most clearly at the proper right shoulder showing an area underneath the thin paint layer that depicts the armour (see Fig.12). This shows that the azurite pigment containing arsenic, which was later used to complete the background of the upper portrait (between the inscribed line and the outer edge of the panel), also appears in the lower portrait (visible at the shoulder) and may indicate the use of the same batch of azurite pigment for both paintings. A cross section taken from this area shows that the background colour

36 Resizing panels, both enlarging and reducing, to incorporate changes to compositions during painting is apparent in the examination of several other paintings by Bronzino and was evidently part of the artist’s practice. For instance, an additional strip on the left side of An allegory with Venus and Cupid permitted the extension of Cupid’s wing and the addition of

the forearm of Jealousy; see Plazzotta and Keith, op. cit. (note 22), p.95, fig.40. Portrait of a young man (1550–55; Nelson-Atkin Museum of Art, Kansas City) is believed to have been cut down during the process of altering the composition; see E.W. Rowlands: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Italian Paintings 1300–1800, Kansas City

of the lower portrait was a pale, cool grey made from carbon black, lead white and a small amount of the azurite containing the arsenic anomaly (see Fig.17).

Other elemental maps, such as the lead and mercury maps, clarify the contours of the sitter’s cloak and broad hat (see Figs.8 and 9). The elegant garments as well as the book indicate that the sitter was a member of the elite whose appearance is reminiscent of the aristocrat and scholar depicted in an earlier portrait by Bronzino, Ugolino Martelli (1537–38; Staatlische Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin).38 The art historian Elizabeth Cropper has studied the influence of Bronzino’s teacher and mentor, Jacopo Carruci, known as Pontormo (1494–1557), on his pupil’s early portraits.39 Comparing Bronzino’s Portrait of Guidobaldo della Rovere (1532; Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence) with Pontormo’s Portrait of a halberdier (1529–30; J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), she notes that it is the ‘head and shoulders that are closely replicated here. The threequarters format, the way the head is set on the shoulders, the center line of the chest, [. . .] the simplicity of the green curtained background, and, above all, the direct gaze, all confirm that Bronzino had his teacher’s most recent portrait in mind’.40 Pontormo’s influence was evidently still being felt in the lower portrait Bronzino began on the Sydney panel, notably in

and Seattle 1996, pp.181–88, no.22.

37 See Simon 1987, op. cit. (note 9), p.388.

38 Inv. no.338A, oil on panel, 102 by 85 cm. Further comparisons with the lower subject can be made with Bronzino’s earlier portraits, most noticeably his Portrait of a young man with a book (1530s; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. no.29.100.16, oil on

panel, 95.6 by 74.9 cm).

39 E . Cropper: Pontormo: Portrait of a halberdier , Los Angeles 1997.

40 Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence, inv. no.21941, oil on panel, 114 by 86 cm.; and J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv. no.89.PA.49, oil on panel transferred to canvas, 95.3 by 73 cm. See Cropper, op. cit. (note 39), p.90.

the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023 13

Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour

19. Composite XRF scan map of Fig.1 showing mercury (red) and iron (green). (© Art Gallery of New South Wales).

20. Red line trace of all features present in the infra-red image and XRF iron, copper, lead and mercury maps of Fig.1 that are not visible on the painting. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives).

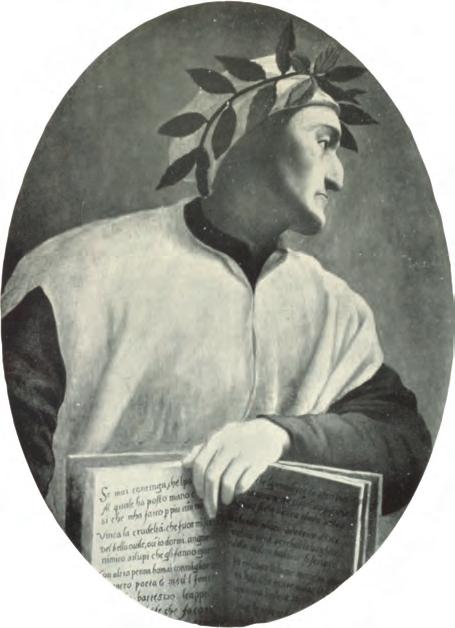

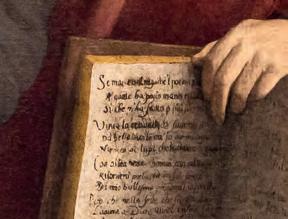

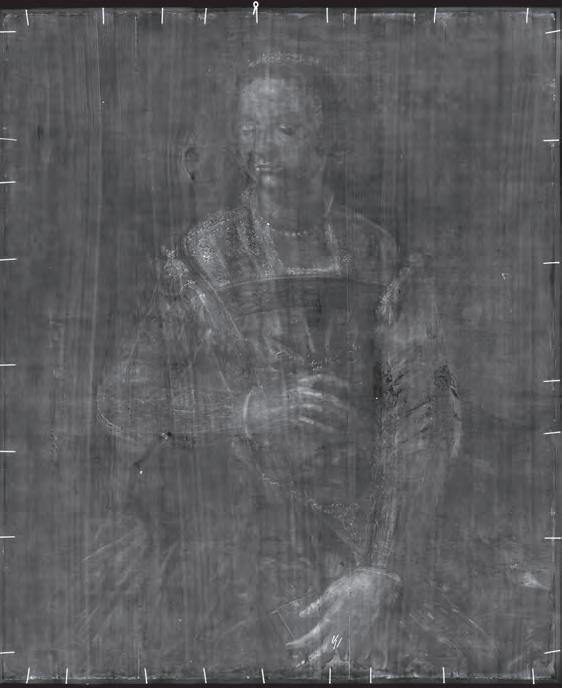

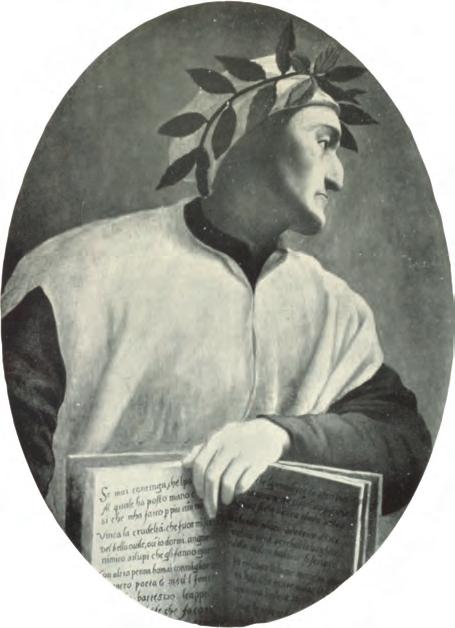

the compositional and chromatic similarities.41 The lower painting shares striking similarities with another portrait by Pontormo which is generally held to depict Cosimo I de’ Medici, Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici (Fig.21). There is a noted correspondence of the overall design, the contour of the sitter’s shoulders, and aspect of the head and facial features, and most compellingly, the lower pair of hands, though Bronzino places them further to the left. These comparisons suggest that Bronzino may have had this particular portrait by Pontormo in mind in his first conception sketched on the Sydney panel.

Given Bronzino’s well-documented propensity for radically reshaping his compositions, one can only speculate on what form the final image might have taken had it been completed. The overpainted figure – with his seated pose, black garb, book in hand and frontal gaze, set against a pale neutral background – may be placed between Bronzino’s early compositions still influenced by Pontormo and a later painting of an unidentified sitter, Portrait of a young man (Fig.24).42 The similarity of the overall composition and the sitter’s dress as well as the facial likenesses are compelling.

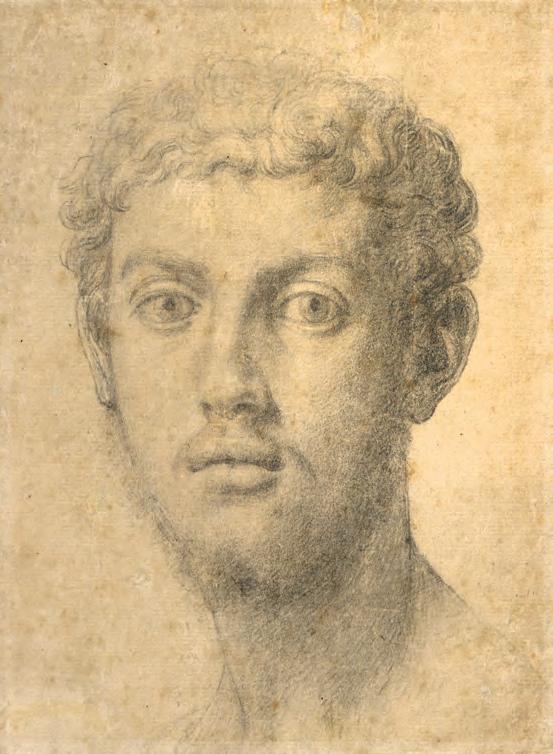

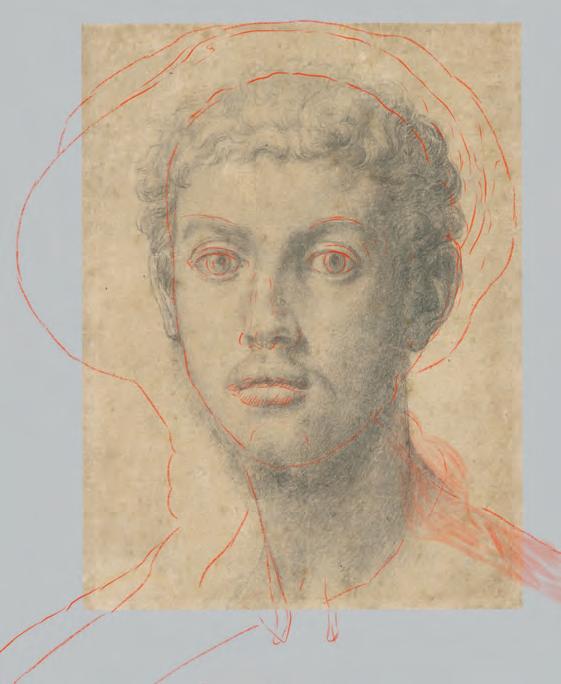

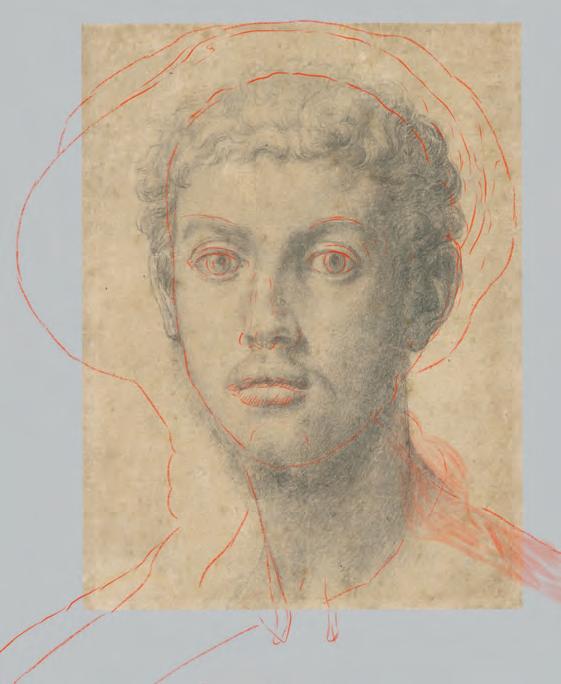

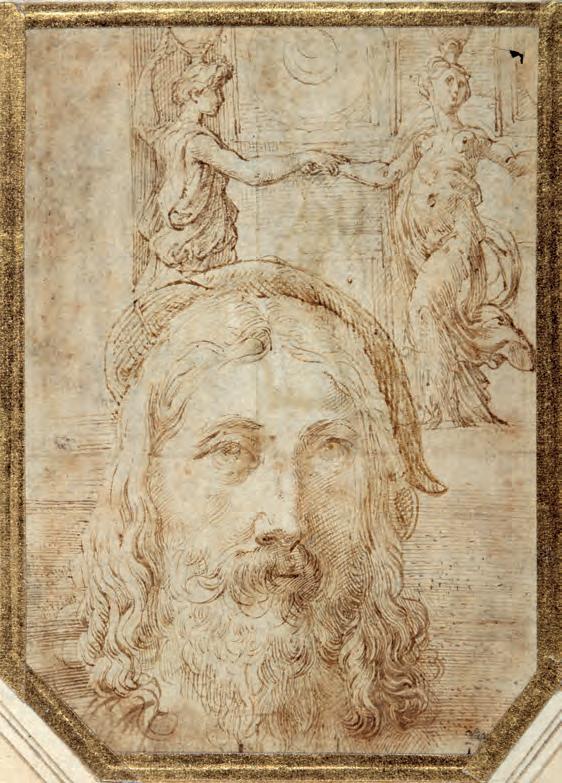

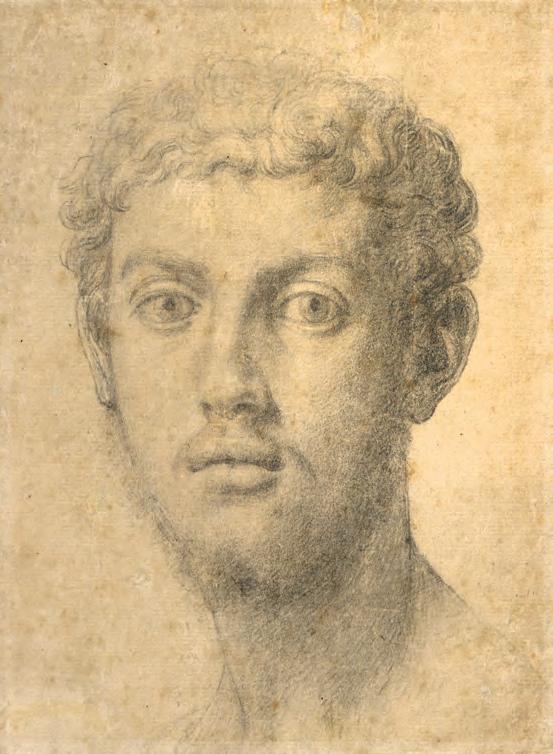

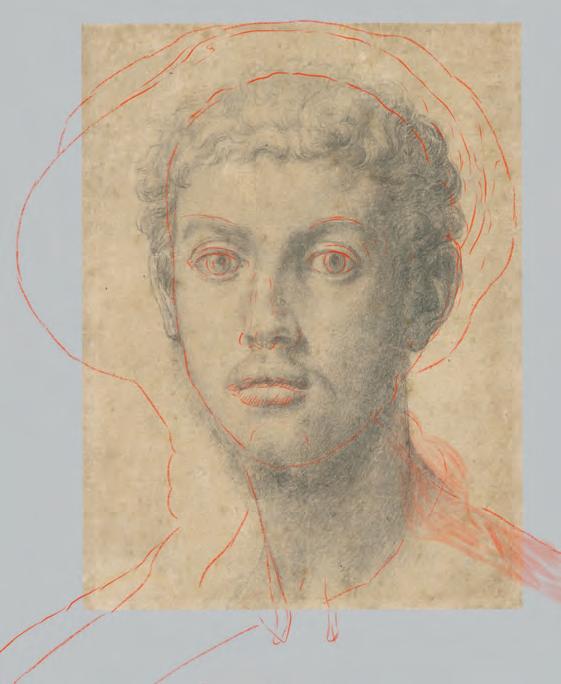

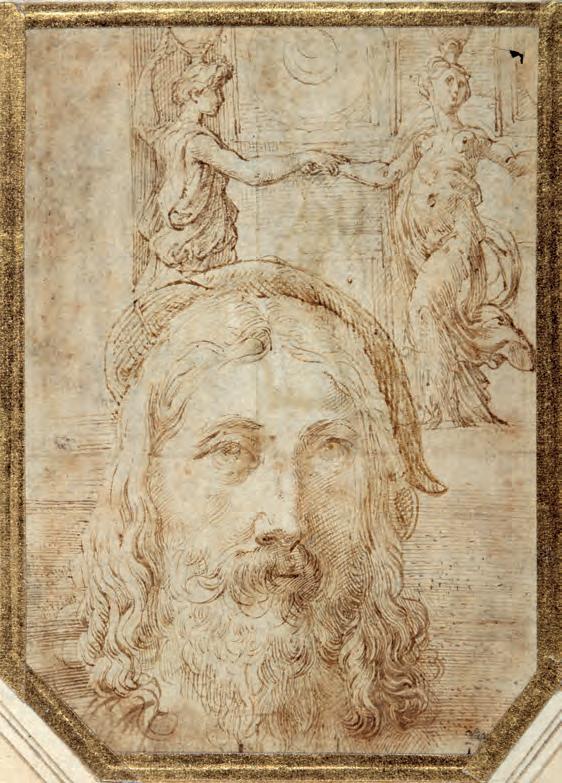

A rare drawing by Bronzino, Head of a man (Fig.22), which has been identified as being a study for the Nelson-Atkins Portrait of a

21. Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici, half-length, in a black slashed doublet and a plumed hat, holding a book, by Jacopo Pontormo. c.1537–

38. Oil (or oil and tempera) on panel, 100.6 by 77 cm. (Private collection; Bridgeman Images).

22. Head of a man, by Agnolo Bronzino. c.1550–55. Black chalk on paper, 13.8 by 10.3 cm. (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles).

young man, was digitally rescaled and layered with a tracing of the face of Sydney lower painting (Fig.23). 43 The degree of alignment of the facial features is remarkable, with the rounded eyes and the contours of the face matching almost exactly. Furthermore, the soft hat and black cloak, the overall posture of the sitter, the shape of the outer contour of his shoulders as well as the position of his right hand suggest a close proximity between the two compositions (see Fig.24). Any direct relation to the Nelson-Atkins Portrait of a young man and the Getty drawing is complicated, however, by the fact that the unfinished Sydney portrait was carried out at least five years before the accepted date (c.1550–55) of the Nelson-Atkins portrait.

Details of the development of the Nelson-Atkins portrait were revealed by a thorough technical study conducted in the early 1990s.44

In an intriguing reversal of the sequence discovered on the Sydney panel, the study showed that the young man portrayed in a cloak had been initially conceived wearing armour. The sitter’s left hand was initially absent, hidden behind an ovoid shield with the right hand resting on something, possibly a helmet. The sitter then underwent a radical change of costume, exchanging the armour for a doublet, and finally the cloak and hat, which are similar to those worn by the subject of the lower Sydney painting. The Nelson-Atkins young man’s hands hold a sword, while the Sydney sitter rests his lower right hand on something not apparent or not depicted. Bronzino’s capacity to radically transform a single work from a figure in armour to one in a cloak and hat, as revealed by the examination of the Nelson-Atkins portrait, is interesting to keep in mind when considering the Sydney panel. The hidden portrait mapped

the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023 14

Focus on Bronzino

23. Fig.22 superimposed on the face of the Sydney lower painting red line trace in Fig.20. (Photograph © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives).

24. Portrait of a young man, by Agnolo Bronzino. 1550–55. Oil on panel, 85.73 by 68.58 cm. (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City), and Fig.20 superimposed. (Photograph © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives).

at the Synchrotron is of sufficient clarity to reveal the dynamic working method inherent in Bronzino’s creative process. The multiple hands along with the variations in the face also support Simon’s identification of two conceptions of a single portrait in progress.

If the likeness to Cosimo is accepted, the lower painting could be read as a preceding attempted portrait of the duke as an elegant gentleman and scholar rather than a warrior. If this concept was then rejected by Bronzino for a more forceful depiction of the duke in armour, in greater accord with the requirements for ‘a man capable of battle but triumphing through peaceful means’, the latter was originated on a new panel, the portrait in the Uffizi.45 Alternatively, it is possible that the lower Sydney painting is the development of an unrelated portrait of a young Florentine nobleman, whose identity is currently unknown. This initial attempt was eventually abandoned, and the panel was instead used to expand the primary half-length Uffizi composition to create the primary three-quarter-length version of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour. If the lapse of time between the execution of the two portraits of the Sydney panel is still unclear, the similar chemical composition of the azurite used in the background of both suggests some proximity. However, the resemblance of the lower Sydney painting to the Nelson-Atkins Portrait of a young man – the similarity of the composition and the apparent use of the Getty drawing as the basis for the sitter’s face in both cases as well as the comparable neutral coloured background – suggests that the two paintings are related. It is possible, therefore, that the Nelson-Atkins panel represents the completion of the abandoned portrait, which was not, therefore, a depiction of Cosimo.46

Although ultimately not carried out, the decision to reduce the three-quarter-length format may have been a response to Cosimo’s preference for a replica without additional inventions, as in the case of the replica altarpiece for Eleonora di Toledo’s chapel. Or perhaps Bronzino was unsatisfied with the extended composition, because either of its awkward placement of the hips, necessitated by a need to show the broncone attached to the tree trunk, or the overall composition being squeezed into a less than ideal pre-determined size. These modifications have been revealed as artistic deliberations rather than simple copying errors and they indicate an original composition that was worked on by the master. In undertaking the portrait of the young duke using the format of a panel that had already been partially painted, Bronzino achieved an enduring archetype, the most successful portrait of the recently appointed ruler of Florence.

41 Other indications of Bronzino’s early style, such as an architectural background, are, however, absent.

42 Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, inv. no.49-28, oil on panel, 85.7 by 68.6 cm.

43 J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv. no.90.GB.29, black chalk on paper, 13.8 by 10.3 cm. On this drawing and its link to the Nelson-Atkins painting, see C.C. Bambach et al.: exh. cat.

The Drawings of Bronzino, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2010, pp.204–05, no.54.

44 See Rowlands, op. cit. (note 22), pp.181–88, no.22.

45 Simon, op. cit. (note 5), p.535.

46 Since the submission of the

present article, a further attempt has been made to identify the sitter of the Nelson-Atkins portrait. In K. Christiansen and C. Falciani, eds: exh. cat. The Medici, Portraits and Politics 1512–1570, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2021, pp.256–57, the authors propose to identify the sitter with Francesco Guadagni, a young nobleman descendant of the newly established Florentine branch of the Guadagni family, and the rising son of one of Bronzino’s important patrons. This identification would consolidate the hypothesis of the sitter’s Sydney lower painting as a young aristocrat representative of the new Florentine society.

the burlington magazine | 165 | january 2023 15

Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour

23. Fig.22 superimposed on the face of the Sydney lower painting red line trace in Fig.20. (Photograph © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives).

24. Portrait of a young man, by Agnolo Bronzino. 1550–55. Oil on panel, 85.73 by 68.58 cm. (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City), and Fig.20 superimposed. (Photograph © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives).

at the Synchrotron is of sufficient clarity to reveal the dynamic working method inherent in Bronzino’s creative process. The multiple hands along with the variations in the face also support Simon’s identification of two conceptions of a single portrait in progress.

If the likeness to Cosimo is accepted, the lower painting could be read as a preceding attempted portrait of the duke as an elegant gentleman and scholar rather than a warrior. If this concept was then rejected by Bronzino for a more forceful depiction of the duke in armour, in greater accord with the requirements for ‘a man capable of battle but triumphing through peaceful means’, the latter was originated on a new panel, the portrait in the Uffizi.45 Alternatively, it is possible that the lower Sydney painting is the development of an unrelated portrait of a young Florentine nobleman, whose identity is currently unknown. This initial attempt was eventually abandoned, and the panel was instead used to expand the primary half-length Uffizi composition to create the primary three-quarter-length version of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour. If the lapse of time between the execution of the two portraits of the Sydney panel is still unclear, the similar chemical composition of the azurite used in the background of both suggests some proximity. However, the resemblance of the lower Sydney painting to the Nelson-Atkins Portrait of a young man – the similarity of the composition and the apparent use of the Getty drawing as the basis for the sitter’s face in both cases as well as the comparable neutral coloured background – suggests that the two paintings are related. It is possible, therefore, that the Nelson-Atkins panel represents the completion of the abandoned portrait, which was not, therefore, a depiction of Cosimo.46

Although ultimately not carried out, the decision to reduce the three-quarter-length format may have been a response to Cosimo’s preference for a replica without additional inventions, as in the case of the replica altarpiece for Eleonora di Toledo’s chapel. Or perhaps Bronzino was unsatisfied with the extended composition, because either of its awkward placement of the hips, necessitated by a need to show the broncone attached to the tree trunk, or the overall composition being squeezed into a less than ideal pre-determined size. These modifications have been revealed as artistic deliberations rather than simple copying errors and they indicate an original composition that was worked on by the master. In undertaking the portrait of the young duke using the format of a panel that had already been partially painted, Bronzino achieved an enduring archetype, the most successful portrait of the recently appointed ruler of Florence.

41 Other indications of Bronzino’s early style, such as an architectural background, are, however, absent.

42 Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, inv. no.49-28, oil on panel, 85.7 by 68.6 cm.

43 J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv. no.90.GB.29, black chalk on paper, 13.8 by 10.3 cm. On this drawing and its link to the Nelson-Atkins painting, see C.C. Bambach et al.: exh. cat.

The Drawings of Bronzino, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2010, pp.204–05, no.54.

44 See Rowlands, op. cit. (note 22), pp.181–88, no.22.

45 Simon, op. cit. (note 5), p.535.

46 Since the submission of the