17 minute read

Discoveries in the Parma baptismal

Rome), but most significantly in this context in a painting by Bronzino of Cosimo I in the guise of Orpheus (Fig.15). The lira da braccio behind Petrarch is very similar to the one Cosimo is playing; it could almost be the other side of the same object. Its role, however, is entirely different. The instrument is not being used to please the ears of listeners, as in the portrait of Cosimo, but is tied to a tree, where it is mute. This intriguing concetto is no doubt intended to indicate the strong tie between Petrarch’s poetic lira and his lover and muse, Laura. This interpretation is supported by the lines in Petrarch’s open book (Fig.13).12 In this late poem from the Canzoniere, written many years after the death of Laura, Petrarch looks back on the poetry of his youth, when Laura was still alive and his heart was consumed by an amorous fire. His verse had been in a sense feeble and erratic (‘ma l’ingegno et le rime erano scarse / in quella etate ai pensier’ novi e ’nfermi’). Now the fire is dead, ‘covered by a small piece of marble’ (‘Quel foco è morto, e ’l copre un picciol marmo’). If she had lived on, he would have made verses with power (‘armato’), that would cause ‘stones to break with my words, and weep with sweetness’ (‘con stil canuto avrei fatto parlando / romper le pietre, et pianger di dolcezza’). The poem is both a lament for Laura and a meditation on the author’s poetics.

Although the sonnet was not among Petrarch’s most famous, it was well known and appreciated. Pietro Bembo singled it out for analysis in his Prose della Volgar Lingua (1525), for instance, and both Adrian Willaert and Orlando di Lasso composed madrigals using the text.13 Yet it is not clear why this poem was chosen for the painting, nor is it known if it was selected by Bettini or Bronzino, who was both a poet himself and an expert on Petrarch.14 Assuming that the texts chosen for the series were related programmatically, some connection with the choice of the canto in the Dante portrait would be expected. The first lines of Dante’s text read: ‘If it ever happens that the sacred poem / To which both heaven and earth have set their hands, / So that it made me thin for many a year, / Should overcome the cruelty which shuts me out / From that lovely fold, where I slept, a lamb, / The enemy of wolves who war against it; / With a different voice now, and with different fleece / I shall come back poet’.15

Advertisement

Dante is referring here to his banishment from the city and an imagined return. The choice of this passage for Bettini’s Dante has so far been discussed only in terms of its political implications. The mention of banishment has been connected to the fact that Bettini had been among the supporters of the republic that had in 1530 been so violently replaced by the rule of Alessandro de’ Medici. Possibly as a result, Bettini left Florence for Rome some four years after the probable date of the painting of Dante. 16 But there always was something incongruous about this explanation for the choice of the text from the Paradiso. If Bettini were expecting to be expelled from Florence shortly, why would he order such a decorative allusion to banishment for a room in the very palazzo that he would soon be forced to leave behind? The Petrarch sonnet provides a context for the quotation from Dante that is not based on the political circumstances of the patron. This new perspective corresponds better not only with the Petrarch portrait, but also with the iconography of the Venus, which, according to Vasari, was painted by Pontormo for Bettini after Bronzino had been set to work on the camera.

Since the Petrarch poem contains no reference to banishment, it is unlikely that this was intended to be the topic linking the portraits. It is striking that in the case of the Dante the author refers to his own poetry, just as Petrarch does in his sonnet, and that there too the poet states that now, late in his life and poetic career, his poetry may change, and could henceforth be of a different nature: ‘With a different voice now, and with different fleece I shall come back poet’ (‘con altra voce omai, con altro vello ritornerò poeta’). The return Dante referred to was not just a possible return to Florence, but also, in a more general sense, a return from his privileged visit to Paradise and his meeting there with Beatrice, who had died years before. Both passages, therefore, refer to poetics and to stylistic changes in relation to the death of a beloved woman who was also a muse. Both authors in addition make clear how their devotion to their respective loved one continued after she had died. It seems, therefore, that there was a shared theme in the painted texts. Their correspondence is close

12 G. Contini and D. Ponchiroli, eds: “Il Canzoniere” di Francesco Petrarca, Turin 1964, 1992 (rev. edn), p.378. The closed book with a crimson cover partly visible behind the poet and under his left arm has no title shown, but in the context of the painting as dicussed in the present article it could be the Trionfi, with its meditations on love and death. 13 P. Bembo: Opere in volgare, Florence 1961, ed. M. Marti, pp.337–38. 14 The seminal study of Bronzino as a poet is D. Parker: Bronzino, Renaissance Painter as Poet, Cambridge 2000. 15 ‘Se mai continga che ’l poema sacro / al quale ha posto mano e cielo e terra, / sì che m’ha fatto per molti anni macro, / vinca la crudeltà che fuor mi serra / del bello ovile ov’io dormi’ agnello, / nimico ai lupi che li danno guerra; / con altra voce omai, con altro vello / ritornerò poeta [. . .]’, D Alighieri: Divina Commedia, III, canto 25, transl. C.H. Sisson, Oxford and New York 1981. 16 See R. Leporatti: ‘Venere, Cupido e I poeti d’Amore / Venus, Cupid and the Poets of Love’, in Falletti and Katz Nelson, op. cit. (note 6), pp.64–89. Here, although the idea of ‘twofold love’, earthly and celestial, is discussed, ‘the political significance’ is stressed as being inescapable: ‘just a few months after the fall of the Republic: Bettini, an active partisan, lived in fear of being 16. Six Tuscan poets, by Giorgio Vasari. c.1544. Oil on panel, 132.1 by 131.1 cm. (Minneapolis Institute of Art; Bridgeman Images).

forced to share in Dante’s same fate’, ibid., p.72. 17 For discussions about the meaning of the Bettini Venus, see, for instance, Falletti and Katz Nelson, op. cit. (note 6); Leporatti, op. cit. (note 16); Aste 2015, op. cit. (note 6), pp.134–74; and Compton, op. cit. (note 12). 18 ‘Le rime, le quai già fece sonore / la voce giovinil ne’ vaghi orecchi / e che movien de’ mia pensier parecchi / a quel desio che m’infiammava il core, / scrivendole come dettava Amore, / Àn facto chiocce gli anni gravi et vecchi, / Poscia che morte ruppe quelli specchi, / Da’ quai forza prendea lo mio vigore / E, come ‘l viso angelico tornossi / al regno là, dond’era a noi venuto / per farne fede dell’altrui bellezza, / e i passi miei di drieto a llui fur mossi, / né rima poi né verso m’è piaciuto, / né altro che ‘l seguir la sua altezza’, A.F. Massèra, ed.: Giovanni Boccaccio, La caccia di Diana e le Rime, Turin 1914. pp.140–41. 19 For the requirements for membership, see Aste 2015, op. cit. (note 6), pp.45–54 and 61. It was possible to gain entrance with the translation of a Latin text into Tuscan, but there is no indication that Bettini was a classicist. 20 See R. Aste: ‘Bettini’s splendore: the camera’s physical and social functions’, in idem 2015, op. cit. (note 6), pp.175–208.

enough to imply that it was intentional and meant to be noticed, although the fact that the paintings were installed high up in lunettes makes one question how legible they would have been in reality. In a general sense the theme recalls many statements about love made at this time, both verbal and visual, and in particular the common distinction between two kinds of love: one lower and earthly, and the other sublime and celestial. This also appears to be a main theme of Michelangelo’s enigmatic design for Pontormo’s Venus. Bettini’s camera may have been intended as a visual display of such a notion about the nature of love as well as a celebration of the tre corone fiorentine ‘who have sung of love’.17

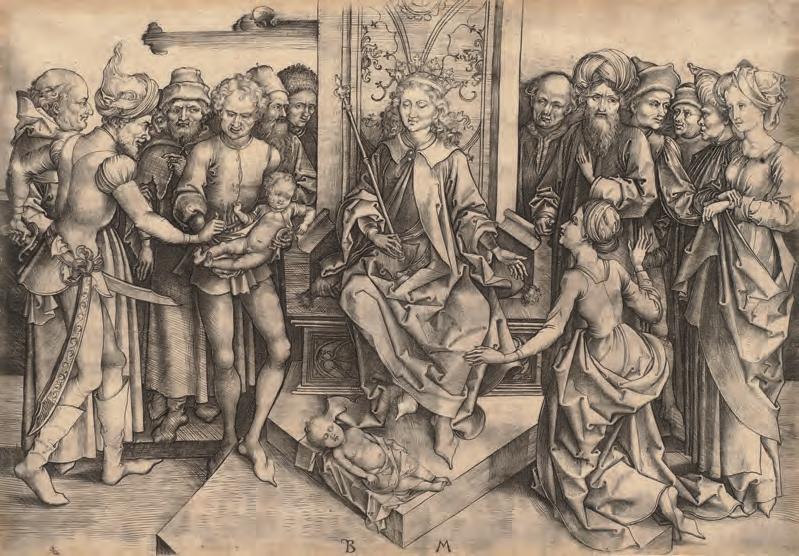

When discussing Bronzino’s portraits of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio for Bettini, Vasari refers rather ambiguously to the intention of adding ‘all the other poets who have sung of love in Tuscan prose and verse’. Boccaccio’s reputation as a vernacular poet has been overshadowed by the success of the Decameron, which is in prose. If he were portrayed by Bronzino with poetry that would have fitted with the programme of Bettini’s camera, what might it have been? Boccaccio wrote entire series of sonnets in a Petrarchan or Dantesque vein, and he had his own equivalent of Beatrice and Laura, a lady nicknamed Fiammetta (little flame) although unlike Dante and Petrarch, he had a sexual relationship with his adored lady and muse. Her early death led to a number of moving verses. So, Boccaccio, like Dante and Petrarch, has a poetic œuvre split in two – before and after the death of his muse. His corpus of sonnets also contains a reference to a change in the poet’s voice after the death of Fiammetta. In a sonnet that has intertextual relations both to Dante and Petrarch, Boccaccio recalls ‘The verses that once my youthful voice / Made resound in willing ears / On a par to the desire that enflamed my heart / Writing them as Amor dictated’, and reflects that in his ‘grave and elder years’, after the death of his beloved, they seem like ‘cackle’.18 The sonnet’s sequel tells us how the poet now aspires to follow her into the celestial sphere, ‘To pay our homage to that other beauty’, concluding that ‘Song or verse pleased me no longer / Other than the following of her loftiness’. This is reminiscent of Dante’s altro vello e altro voce after his encounter with Beatrice in Paradise, or Petrarch’s more mature style, stil canuto, developed after the death of Laura. The inclusion of such a poem in the portrait of Boccaccio would have given coherence to what has been suggested may have been the programme of the camera, but it is also quite possible that the portrait deferred to Boccaccio’s reputation as primarily a prose writer and incorporated no poetry at all.

As Michelangelo’s trusted banker, Bettini is mentioned a number of times in the artist’s letters from Rome to his cousin Leonardo in Florence in the 1540s. In the same years Benedetto Varchi wrote a long scholarly commentary on one of Michelangelo’s sonnets, the famous ‘Non ha l’ottimo artista alcun concetto’ (‘Nothing the best of artists can conceive’). According to a letter of 1549 from Michelangelo to Leonardo, the commentary was forwarded to the artist in Rome through Bettini as an intermediary, indicating that he was more than a banker and belonged to a circle of Florentines, including Varchi and Michelangelo, who were deeply interested in poetry and art. Varchi’s Due Lezzioni (1549) was not only dedicated to Bettini but even contained a sonnet in his honour. Bettini was admitted as a member of the Accademia Fiorentina, founded by Cosimo I in 1542, and he came to be a kind of cultural ambassador in Rome. Membership of the Accademia was granted only to someone who had submitted poetry.19 Bettini presumably had tried his hand at writing poems himself, probably by the time he ordered the decoration of his camera on the themes of love and poetry; it is tempting to speculate even that he had a personal reason for this choice. It is possible, however, as suggested above, that the programme was Bronzino’s invenzione, given his literary expertise, the frequency with which he introduced books into his works and the complete originality of these portrait compositions.

Consideration of the room’s programme raises the important question of the function of the camera for which these works were destined. If an allusion to love enduring beyond death was intended, such a theme would have been most appropriate for a camera da letto (bedroom), but a case has also been made that it was a camera privata or studiolo. Richard Aste has recently presented an overview of the various arguments in favour of either possibility.20 Given Vasari’s reference to additional portraits being planned for the room, and considering the position of the tre corone in high lunettes

17. Petrarch, by a follower of Cristofano di Papi dell’Altissimo. c.1560. Oil on panel, 63 by 49 cm. (Palazzo Pitti, Florence; courtesy Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi). 18. Dante, by a follower of Cristofano di Papi dell’Altissimo. c.1560. Oil on panel, 63 by 49 cm. (Palazzo Pitti, Florence; courtesy Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi). 19. Boccaccio, by a follower of Cristofano di Papi dell’Altissimo. c.1560. Oil on panel, 65 by 51 cm. (Palazzo Pitti, Florence; courtesy Gabinetto Fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi).

20. Proposed reconstruction of Figs.3, 8 and 22 as they might have appeared in the camera of Bartolomeo Bettini.

21. Allegorical portrait of Dante, by Carlo Dolci after Agnolo Bronzino. Red and black chalk on paper, 23.2 by 20.1 cm. (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Bridgeman Images). 22. Boccaccio holding a copy of the ‘Decameron’, attributed to a follower of Cristofano di Papi dell’Altissimo. c.1570. Oil on canvas, 70 by 94.2 cm. (Private collection).

and the fact that they are portrayed with books, an arrangement like a studiolo seems more likely – also because Vasari, as we have seen, mentions that more portraits had been planned. Evidence, however, is lacking; we do not even know the location of Bettini’s house at this time.

Now that the appearance of Bronzino’s Petrarch has been rediscovered, it is tempting to speculate about the appearance of the third of Bettini’s tre corone, the portrait of Boccaccio. Extrapolating from the Dante and Petrarch, it seems likely that it would have incorporated the following features: a seated half-length gure wearing a laurel crown, not looking straight at the spectator, slightly seen from below and accompanied by an open book with legible text. There is no obvious trace of such a prototype among the known Boccaccio portraits,21 but these di er considerably from each other and there appears to be no clearly established Boccaccio type.22 It has been hypothesised that when Vasari painted his Six Tuscan poets (Fig.16) for Luca Martini – who in 1555 had his portrait painted by Bronzino (Palazzo Pitti, Florence) – he may have based the Petrarch and Boccaccio

on Bronzino’s portraits, an idea supported by the fact that Vasari had briefly been in Bronzino’s workshop and was apparently well-informed about Bettini.23 However, Vasari’s Dante does not resemble Bronzino’s, and now that Bronzino’s Petrarch composition has been identified, it is clear that this was not a model for the Six Tuscan poets either.

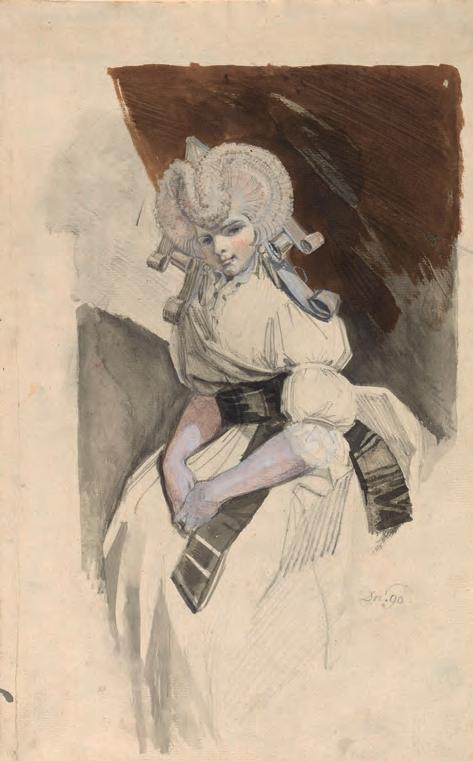

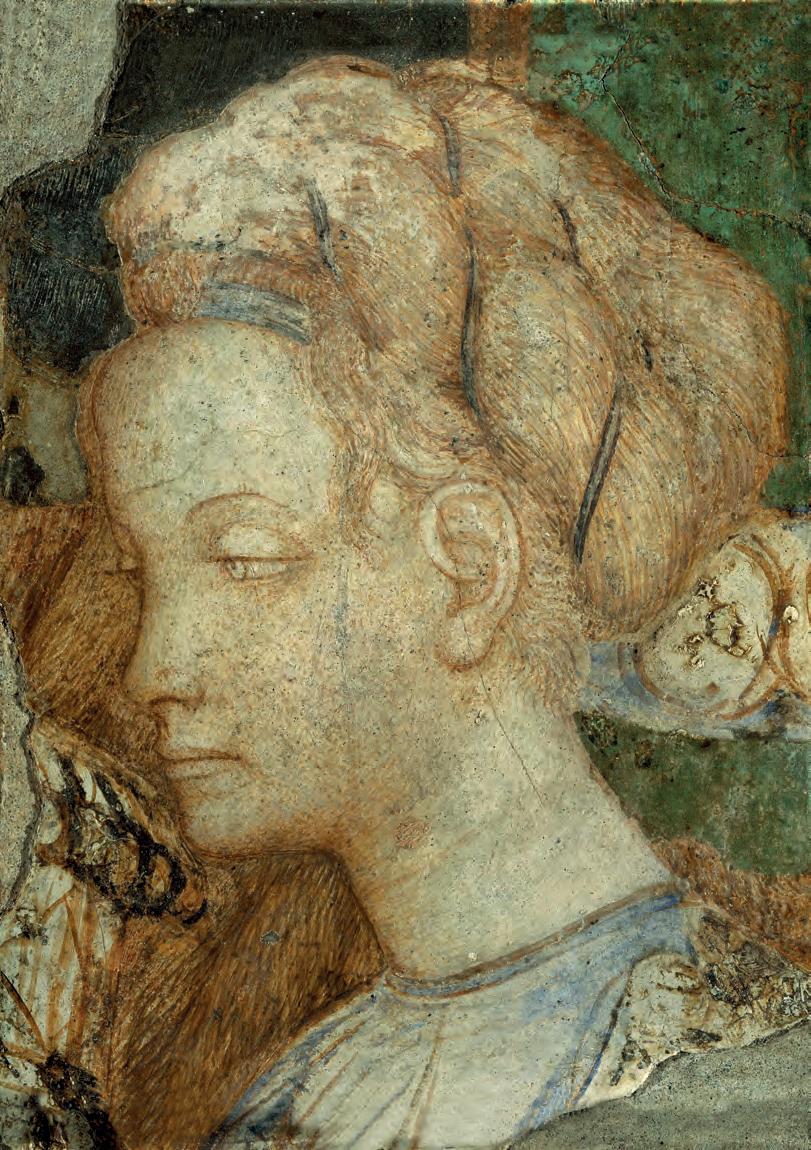

There is also no connection between the Bronzino compositions and the portraits of the three poets in the famous series of copies made by a follower of Cristofano di Papi dell’Altissimo for Cosimo de’ Medici of portraits in Paolo Giovio’s celebrated museum in Como, the majority of which are now preserved in the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. However, a comparable but lesser-known series of portraits by an unknown painter (or painters), now in Palazzo Pitti, Florence, includes a close variant not just of Bronzino’s Dante, but of Petrarch as well (Figs.17 and 18). It might be assumed, therefore, that the Boccaccio in the series (Fig.19) might also be an echo of a composition by Bronzino, but it is in fact derived largely from the older Boccaccio in the Giovio series.

Bettini’s Dante and Petrarch make it clear that Bronzino created new portraits for his patron, without any reliance on copying. Among their innovatory qualities is a vision of the poets that was appropriate for their placement in high lunettes and emphasised their elevated status and detachment from earthly concerns, features that are lacking in the Boccaccio in the Altissimo series. The head of Boccaccio in Vasari’s Six Tuscan poets, by contrast, conforms surprisingly well with such an elevated view, making it sit rather awkwardly within the group. It clearly relates to a different spatial context, one that might conceivably accord with Bettini’s camera.

In 2004 a painting of Boccaccio was sold at Sotheby’s, London, which has many features that correspond with Bettini’s Dante and Petrarch portraits (Fig.22).24 It is half-length and the sitter, who wears a laurel crown and looks away from the viewer, holds a book, probably the Decameron, which, however, is closed. The facial features are different from other imaginary Boccaccio portraits, although the pose corresponds with the figure of Boccaccio in Vasari’s Six Tuscan poets. While at first sight there is little to connect this portrait with Bronzino, elements that point to his period or circle include the style of the furniture, the way the chair is foreshortened, the sideways glance and the exaggeratedly elegant treatment of the hands, which can be compared to those in Bronzino’s portraits painted around the same time as the Dante and Petrarch (Figs.23–26). Although cropped, the figure sits surprisingly well in the company of Dante and Petrarch (Fig.20) and so, despite the fact that it does not include a poem, it seems possible to the present author that it is derived from Bronzino’s Boccaccio lunette.25 In all three cases it seems that the light, as indicated by the cast shadows, more or less comes from the upper right, which may suggest the presence of a window there in the original setting.

Bronzino’s paintings for Bettini’s camera were appreciated and copied, as is evident from the copy of the Dante portrait on panel in Washington. A seventeenth-century drawing convincingly attributed to Carlo Dolci (1616–86) is a copy of the complete composition (Fig.21).26 As far as the present author is aware, no drawings of the portrait of Petrarch have been preserved, but, as discussed above, the Petrarch in

21 For the iconography of Boccaccio, see V. Kirkham: ‘L’immagine del Boccaccio’, in V. Branca, ed.: Boccaccio visualizzato: narrare per parole e per immagini fra Medioevo e Rinascimento, Turin 1999, I, pp.83–144. 22 If a possible source has to be sought for a model of a portrait of Boccaccio, the most likely candidate, because of its accessibility and authority, would perhaps be the fresco by Andrea del Castagno painted c.1450 for Palazzo Vecchio, now in the Uffizi. 23 See, among others, Aste 2015, op. cit. (note 6), p.49. 24 Sale, Sothebys, London, Old Masters Sale, 16th April 2002, lot 224, described as ‘Portrait of Boccaccio, half-length, by a follower of Cristofano dell’Altissimo’. 25 The author is grateful to Stijn Stumpel for invaluable help in developing this visual hypothesis, as well as for the initial tentative reconstructions of Figs.14 and 20. 26 For this drawing, see, for example, D. Scrase: ‘A drawing of Dante after Bronzino by Carlo Dolci in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge’,

Clockwise, from top left 23. Detail of Ugolino Martelli, by Agnolo Bronzino, showing the sitter’s left hand. 1536–37. (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin; Bridgeman Images). 24. Detail of Laura Battiferro, by Agnolo Bronzino, showing the sitter’s right hand. 1552. (Palazzo Vecchio, Florence; Bridgeman Images). 25. Detail of Fig.22, showing Boccaccio’s hands. 26. Detail of Guidobaldo della Rovere, by Agnolo Bronzino, showing the sitter’s right hand. c.1544–45. (Palazzo Pitti, Florence; Bridgeman Images).

the sixteenth-century series of portraits uomini famosi is based on the Bronzino type and the prestige of the composition is confirmed by the oval copy attributed to Naldini. Whatever the state and status of the newly identified Petrarch painting, this hitherto unknown image may not only deepen our understanding of this important early phase of Bronzino’s career, but also, more significantly, provides a better idea of what has been called ‘one of the most influential decorative programs of the sixteenth century’, devoted to the three greatest of Tuscan poets, Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio, devised by three of the greatest painters of the Tuscan cinquecento, Michelangelo, Pontormo and Bronzino.27

in M.T. Caracciolo, ed.: Hommage au dessin: Mélanges offerts à Roseline Bacou, Rimini 1996, pp.204–09. For a drawing by Bronzino related to the painted portrait, see C.C. Bambach, J. Cox-Rearick and G.R. Goldner, eds: exh. cat. The Drawings of Bronzino, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2010. 27 Aste 2015, op. cit. (note 6), p.1.