8 minute read

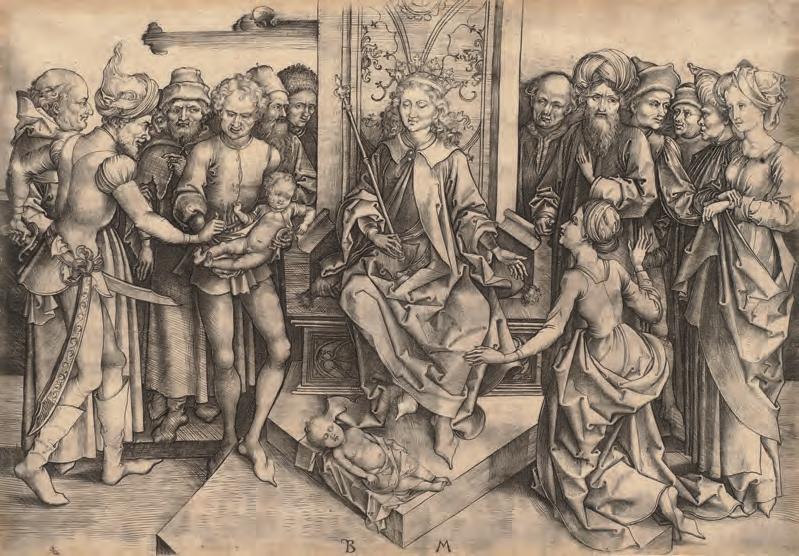

Isamu Noguchi by penelope curtis

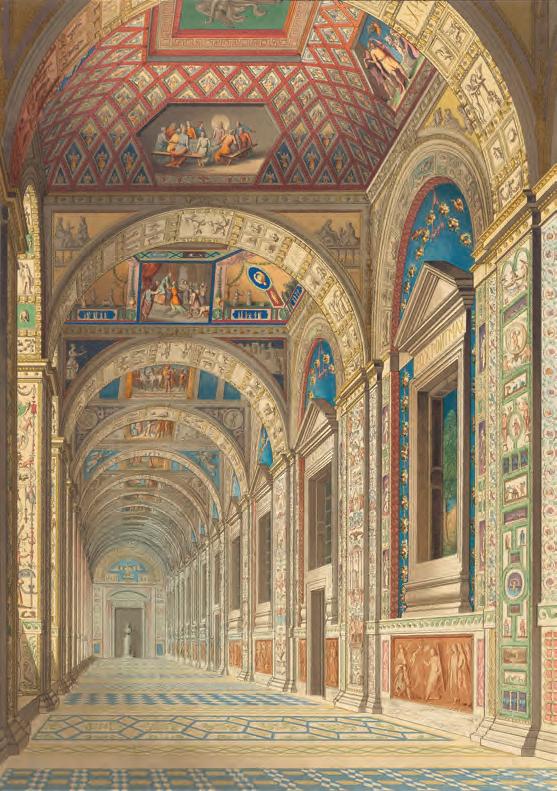

each concludes with a monochrome scene in the dado.28 The frescos are embedded three-dimensionally in the bays in a gently complex rhythm, through which the grotteschi articulate the architectural system; all is beautifully documented by the album of drawings of the frescos commissioned in the 1550s by Giovanni Battista Armenini (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Cod. mim. 33). The use of mosaics in the Chigi Chapel was not ‘utterly revolutionary for the period’, since Peruzzi, their likely author, had just designed mosaics for the entire vault of the St Helena Chapel in S. Croce, Rome, between 1495 and 1509, shortly before the Chigi Chapel (Fig.9);29 and Raphael was never ‘supervisor of Roman antiquities and excavations’.30

The multifaceted exhibition in Rome chose an entirely different approach to that in London. It made clear to visitors at the outset that it honoured the fifth centenary of Raphael’s death by starting with a slightly reduced facsimile by Factum Arte of the artist’s tomb in the Pantheon, surrounded by an allusion to his final achievements through both autograph works and later representations of his death; it then daringly told the story of Raphael’s life backwards, as though he were Benjamin Button. Contrary to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s sad short story, however, this was a witty experiment that released the visitor from the tedious art-historical nitty-gritty of artistic development, evolution and progress by proposing a fresh way of looking at the artist’s works and personality. Exploring the exhibition, or parts of it, backwards was a stimulating option, should a visitor have chosen it.

Advertisement

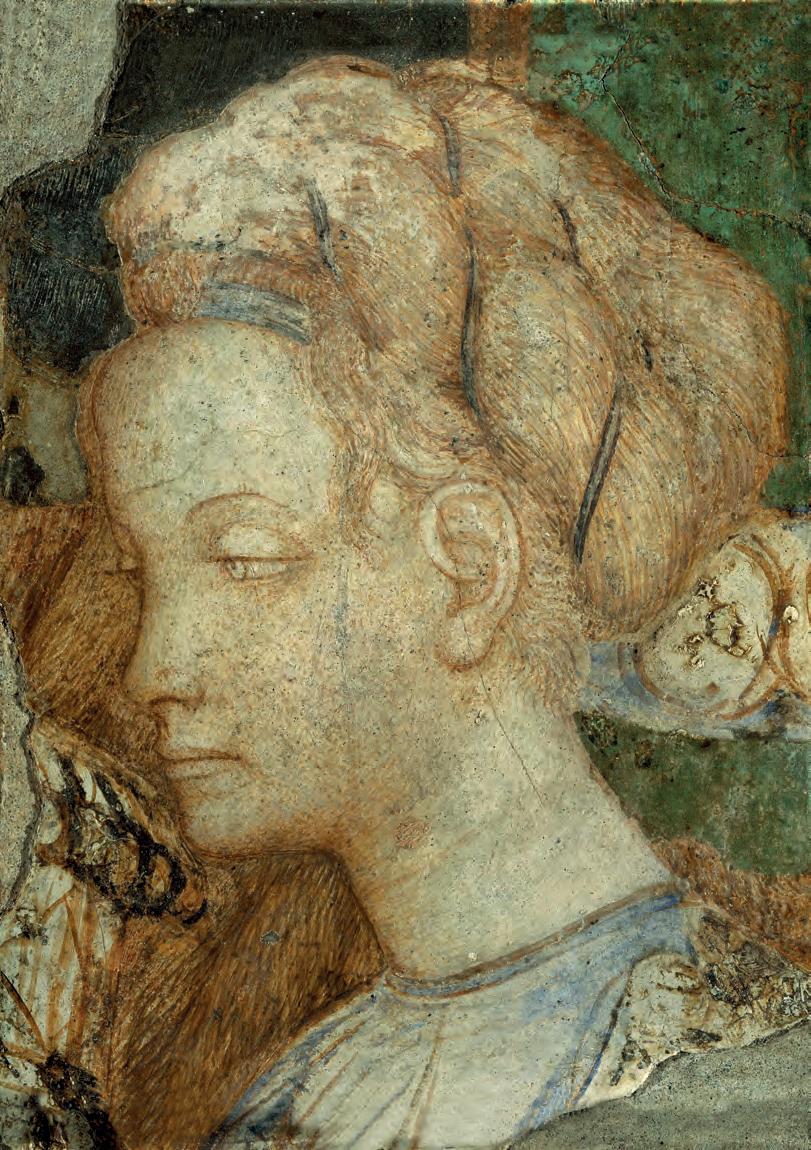

Digital media were employed to contextualise Raphael and his activities and to present a major new scholarly insight into what Raphael describes in his famous letter to Leo X on the remains of ancient Rome. Next to the five surveys by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger of the imperial fora was an animation in which Alessandro Viscogliosi transformed them into three dimensions, leading visually from the actual topography to an understanding of the effort and skill that Raphael’s famous reconstruction of ancient Rome required. The archaeologist, the architect, the painter and the draughtsman were shown to be integrated in his artistic personality, offering the visitor a dialogue between the different media in which he worked and for which he produced designs. In a different virtual enterprise, the curators exploited the educational impact of juxtaposing an original Sistine Chapel tapestry with a dazzling facsimile of its cartoon, an idea repeated in London with a different pairing of cartoon and tapestry. Although the upper rooms of the Scuderie penalise all their exhibitions because of their low ceilings, they were not the cause of the failure to capture the atmosphere, achievement and aura of the Vatican Stanze. Despite some spectacular works that have never travelled before, such as the portrait of Pope Julius II (1511; National Gallery; no.XI.1) or the Tempi Madonna (no.X.16; Fig.4) – also seen in London – Raphael’s early career seemed slightly to fade away, since the early altarpieces were absent. Whosoever they might represent, the inclusion of the portraits La donna velata (Fig.10; no.VII.1), the so-called La Fornarina (Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome; no.VII.5) and the clumsy Portrait of a young woman (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg; no.VII.4), convincingly proved the opposite of what they were meant to demonstrate, since it was evident that, of the three, La donna velata is the only autograph work. Although

9. Vault of the Chapel of St Helena, S. Croce in Gerusalemme, Rome, designed by Baldassare Peruzzi. 1496–1509. Mosaic. (Alamy).

it is thirty-nine years since Shearman said the red-chalk drawing of the vision of Ezekiel in the Museo Horne, Florence (no.V.31), ‘ought to go back to Rubens’,31 it was exhibited here again as being by Raphael, possibly reworked by Rubens (‘Raffaello, poi ripreso da Peter Paul Rubens?’). The stiff Girl’s head (no.XI.7) from a private collection does not charm, and even a century and a half after it was first attributed to Raphael the Portrait of a man in the Liechtenstein collection (no.XI.3) cannot convince. Such details do not lessen Raphael’s reputation, changing only the market value of such works. Our view of the artist’s studio practice is, instead, affected by the question whether the St Cecilia drawing (no.V.3; Fig.11) – in Landau’s and Parshall’s brilliant and too often neglected analysis of Raphael’s interaction and legacy with his printmakers such sheets do not constitute a problem, even if not by the master himself;32 on the contrary – or the red-chalk St Paul preaching in Athens (1515–16; Uffizi; no.V.29) are autograph or by Giovan Francesco Penni and Polidoro.

Moving beyond these exhibitions, it would improve our understanding of Raphael greatly if he could finally be freed from the spell of Vasari, who was a well-informed and valid biographer, but is in no way a source. His Life of Raphael, first published in 1550, belongs to the artist’s afterlife. Smooth in narrative, but opaque in its references, it distorts our image of the artist and in particular our understanding of his workshop, printmaking and totally of his architecture. Shearman’s compilation of the Raphael documents, the closer knowledge of the artist’s creations gained through hands-on experience during the many restorations, and the 1984 exhibition Raffaello Architetto and its catalogue,33 have laid a strong foundation for an independent reconsideration. The two great anniversary exhibitions presented their Raphaels in the opposite directions of their visitor tours, and not only in their chronological ordering: London promoted Raphael’s genius – quite explicitly – as a commercial product; Rome fostered an intellectual dialogue with an inspiring personality. Ultimately, Raphael died five hundred years ago and we are on our own; his ‘beautiful things help us by being just what they are’.

10. Portrait of a woman (‘La donna velata’), by Raphael. c.1513–14. Oil on canvas, 82 by 60.5 cm. (Palazzo Pitti, Florence). 11. St Cecilia, attributed to Giovanfrancesco Penni. c.1514. Graphite, pen and ink and wash with white lead on paper, 26.8 by 16.3 cm. (Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris).

28 Ibid., pp.32. The dado in the fifth bay has been altered and is unclear. 29 T. Henry in Ekserdjian and Henry, op. cit. (note 18), p.236. 30 K. Granavis: ‘Chronology’, in Ekserdjian and Henry, op. cit. (note 17), pp.291–93 at p.293. 31 J. Shearman: ‘Raphael year: exhibitions of paintings and

drawings, THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE 126 (1984), pp.398–403, at p.398. 32 Landau and Parshall, op. cit. (note 21), p.131. 33 C.L. Frommel et al.: exh. cat. Raffaello Architetto, Rome (Capitoline Museums) 1984, reviewed by Caroline Elam in this Magazine, 126 (1984), pp.452 and 456–57.

Exhibitions

A comprehensive retrospective reveals the full range of Denis Wirth-Miller’s art, too long overshadowed by his friendship with Francis Bacon

Denis Wirth-Miller: Landscapes and Beasts

Firstsite, Colchester 1st October 2022–22nd January 2023

by katharina günther

Curated by James Birch, this retrospective is the largest dedicated to the painter Denis Wirth-Miller (1915–2010) to date, and the first since 2011.1 Of the hundred-or-so works of art, it includes previously unseen pieces by Wirth-Miller and works by his partner, the illustrator Richard Chopping (1917–2008), and his best friend, Francis Bacon (1909–92). The show is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue with texts by Birch, Andrew Wilson, Rachel Joyce and the co-executor of Wirth-Miller’s and Chopping’s estates, Jon Lys Turner, who is also their biographer.2 The exhibition aims to heighten Wirth-Miller’s profile but also makes much of Wirth-Miller’s and Bacon’s private and artistic relationship.3 Unfortunately, these two emphases do not sit well together.

Wirth-Miller is best known for his atmospheric depiction of the East Anglian countryside: he skilfully captured the wind-swept trees in the vast landscape as they stoically defy the elements (Fig.2), or the rain closing in on the flat grasslands while an approaching fog softly changes the mood of the scene. He found his signature style early into his career; through his distinctive use of brushstrokes that could be wildly swirling or even and energetic, he was able to depict movement in vegetation, convey the sound and smell of rain on a country road and the touch of a fresh breeze blowing over the estuary. Instead of portraying specific places, his paintings seem to be universal cyphers, primarily representing a sense of freedom that the artist appears to have found in the open countryside.

Before Wirth-Miller committed himself to painting in 1939, he worked as a fabric designer at the cotton manufacturing company Tootal Broadhurst Lee, Manchester. During the 1940s he trained at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing run by Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines at Benton End. In his early work, Wirth-Miller experimented with Surrealism and Neo-romanticism, with portraiture, figure painting and still life. He soon focused on landscapes, and in 1944 was included in the group exhibition British Landscape Painting at the Lefevre

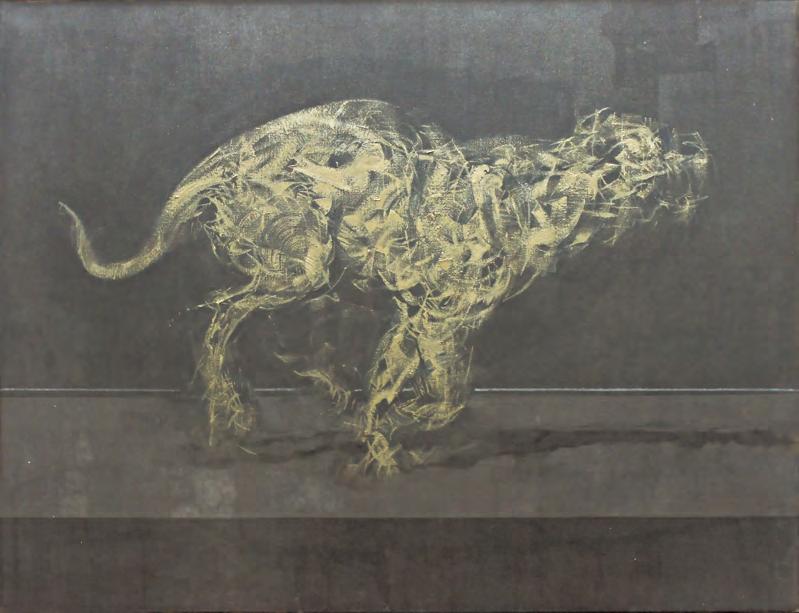

Opposite 1. Walking man, by Denis WirthMiller. c.1954. Oil on canvas, 130 by 99 cm. (Estate of Denis Wirth-Miller; exh. Firstsite, Colchester). 2. Gust of wind, by Denis WirthMiller. 1970–71. Oil on canvas, 76 by 91 cm. (Estate of Denis Wirth-Miller; exh. Firstsite, Colchester). Gallery, London. He also exhibited at other prominent galleries in the city, including the Beaux Arts Gallery, and works by him were acquired by important collections, such as the Arts Council of Great Britain. Yet he never achieved a major breakthrough. WirthMiller abandoned painting in the late 1970s and faded into obscurity.

In the 1940s Wirth-Miller and Chopping bought an old sail store on the quayside of the small town of Wivenhoe, on the Colne Estuary in Essex, which was their home for the remainder of their lives. Well integrated in artistic London bohemia, the couple regularly welcomed illustrious guests, such as the Bloomsbury writer Frances Partridge, the composer Benjamin Britten, and, of course, Bacon, who was probably introduced to them by their mutual friends Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun. Given its proximity to Wivenhoe and its setting within the countryside that provided WirthMiller with the enduring subjects for his paintings, Firstsite is a fitting venue for this exhibition. It is hung roughly chronologically, starting with early