34 minute read

A portrait of the Lady Isabella by the hand of Bronzino by bruce edelstein

For undiscovered reasons, however, the plan to cut the panel and reduce the composition back to the half-length format was not carried out. The green background was therefore continued beyond the incised area to the edges of the panel, this time using the batch of azurite containing trace amounts of arsenic. The small patch of armour at the lower-left waist was reinstated (Fig.18). The background surrounding the part of the broncone, which is underneath the helmet, was also repainted and two small leaves were painted over, leaving in place only the two larger leaves. These minor modi cations revealed by analytical examination can therefore be regarded as true pentimenti on the Sydney version of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour. The three-quarter-length composition, although originally painted in full on the large panel, was extensively modi ed during deliberations whether to reduce it to the half-length format, however, ultimately the decision was to retain the larger format.36 Once completed in its original large format, the portrait was sent to Paolo Giovio, who received it enthusiastically.

The various issues relating to the modi cations of the composition are partially the result of the panel having originally been used for a di erent painting, as revealed in the X-ray, IRR and XRF images. The striking composite image of the two elemental maps of iron and mercury, overlaid and colour-ta ed, gives the best picture of the lower painting, despite being partly obscured by the presence of the overlying portrait (Fig.19). By examining each elemental map in turn and tracing the features that are not visible in the nished painting onto a single image, it is possible further to clarify the underlying work (Fig.20). The image demonstrates Bronzino’s organic approach to composition, dynamically evolving and revising his subject on the panel. The most dramatic feature appears in the mercury map showing the artist’s use of the bright red vermilion pigment (see Fig.9). It provides us with a remarkable image of at least three new hands. This accords well with the hypothesis that we are seeing two di erent conceptions of a single abandoned portrait.37 The fact that the hands appear in the mercury map but only faintly in the lead map shows that they were initial thoughts, thinly sketched in vermilion alone and not yet worked up in pale esh tones with the addition of lead white. The sitter’s left hand can be seen clearly in two di erent positions. The upper attempted hand is strongly drawn, with the index nger extended and holding an open book. The second left hand appears lower down with all ngers extended, possibly resting upon a supporting edge. The sitter’s right hand can be distinctly seen in the lower-left corner, loosely sketched but clearly formed, close to and level with the lower left hand. The

Advertisement

Left, top to bottom 15–17. Paint cross sections and SEM backscattered electron images of the painting illustrated in Fig.1. Locations of sample sites are indicated by the white letters in Fig.18. 15. Paint cross section outside the inscribed line showing two phases of blue/green azurite crystals, one circled in white. 16. Paint cross section of the green background inside the inscribed area showing a single phase of azurite crystals. 17. Paint cross section on the shoulder showing a thin layer of leadbased paint from armour with grey/green background from the l ower painting and a two-phase azurite pigment circled in white. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Paula Dredge). 18. Purple indicates the areas of copper-based azurite background containing arsenic (outside the inscribed line and upper shoulder). Red indicates the area of copper-based azurite background that does not contain arsenic. Green indicates the area of copper-based azurite background not containing arsenic but repainted. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Paula Dredge).

a

b

c a

c

b

Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour

19. Composite XRF scan map of Fig.1 showing mercury (red) and iron (green). (© Art Gallery of New South Wales). 20. Red line trace of all features present in the infra-red image and XRF iron, copper, lead and mercury maps of Fig.1 that are not visible on the painting. (© Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives).

index finger and thumb are extended, perhaps resting on or holding an unknown object. A second right hand may also be visible in an upper position but the overlap with the folds of the sleeve at the elbow makes it difficult to interpret.

Both copper and arsenic maps indicate that there was a background in place for the lower painting before being hidden by the deep green curtain of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour (see Figs.12 and 13). This first background is imaged most clearly at the proper right shoulder showing an area underneath the thin paint layer that depicts the armour (see Fig.12). This shows that the azurite pigment containing arsenic, which was later used to complete the background of the upper portrait (between the inscribed line and the outer edge of the panel), also appears in the lower portrait (visible at the shoulder) and may indicate the use of the same batch of azurite pigment for both paintings. A cross section taken from this area shows that the background colour of the lower portrait was a pale, cool grey made from carbon black, lead white and a small amount of the azurite containing the arsenic anomaly (see Fig.17).

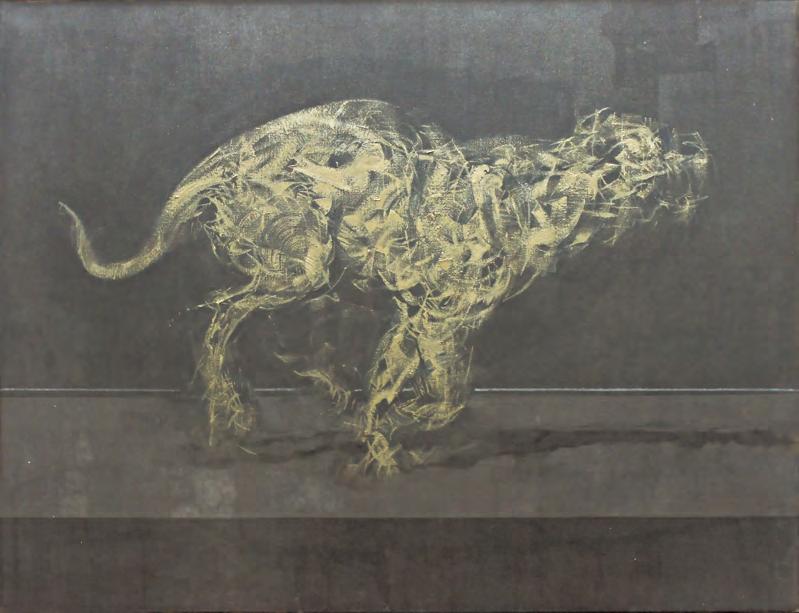

Other elemental maps, such as the lead and mercury maps, clarify the contours of the sitter’s cloak and broad hat (see Figs.8 and 9). The elegant garments as well as the book indicate that the sitter was a member of the elite whose appearance is reminiscent of the aristocrat and scholar depicted in an earlier portrait by Bronzino, Ugolino Martelli (1537–38; Staatlische Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin).38 The art historian Elizabeth Cropper has studied the influence of Bronzino’s teacher and mentor, Jacopo Carruci, known as Pontormo (1494–1557), on his pupil’s early portraits.39 Comparing Bronzino’s Portrait of Guidobaldo della Rovere (1532; Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence) with Pontormo’s Portrait of a halberdier (1529–30; J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), she notes that it is the ‘head and shoulders that are closely replicated here. The threequarters format, the way the head is set on the shoulders, the center line of the chest, [. . .] the simplicity of the green curtained background, and, above all, the direct gaze, all confirm that Bronzino had his teacher’s most recent portrait in mind’.40 Pontormo’s influence was evidently still being felt in the lower portrait Bronzino began on the Sydney panel, notably in

36 Resizing panels, both enlarging and reducing, to incorporate changes to compositions during painting is apparent in the examination of several other paintings by Bronzino and was evidently part of the artist’s practice. For instance, an additional strip on the left side of An allegory with Venus and Cupid permitted the extension of Cupid’s wing and the addition of the forearm of Jealousy; see Plazzotta and Keith, op. cit. (note 22), p.95, fig.40. Portrait of a young man (1550–55; Nelson-Atkin Museum of Art, Kansas City) is believed to have been cut down during the process of altering the composition; see E.W. Rowlands: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Italian Paintings 1300–1800, Kansas City and Seattle 1996, pp.181–88, no.22. 37 See Simon 1987, op. cit. (note 9), p.388. 38 Inv. no.338A, oil on panel, 102 by 85 cm. Further comparisons with the lower subject can be made with Bronzino’s earlier portraits, most noticeably his Portrait of a young man with a book (1530s; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv. no.29.100.16, oil on panel, 95.6 by 74.9 cm). 39 E. Cropper: Pontormo: Portrait of a halberdier, Los Angeles 1997. 40 Galleria Palatina, Palazzo Pitti, Florence, inv. no.21941, oil on panel, 114 by 86 cm.; and J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv. no.89.PA.49, oil on panel transferred to canvas, 95.3 by 73 cm. See Cropper, op. cit. (note 39), p.90.

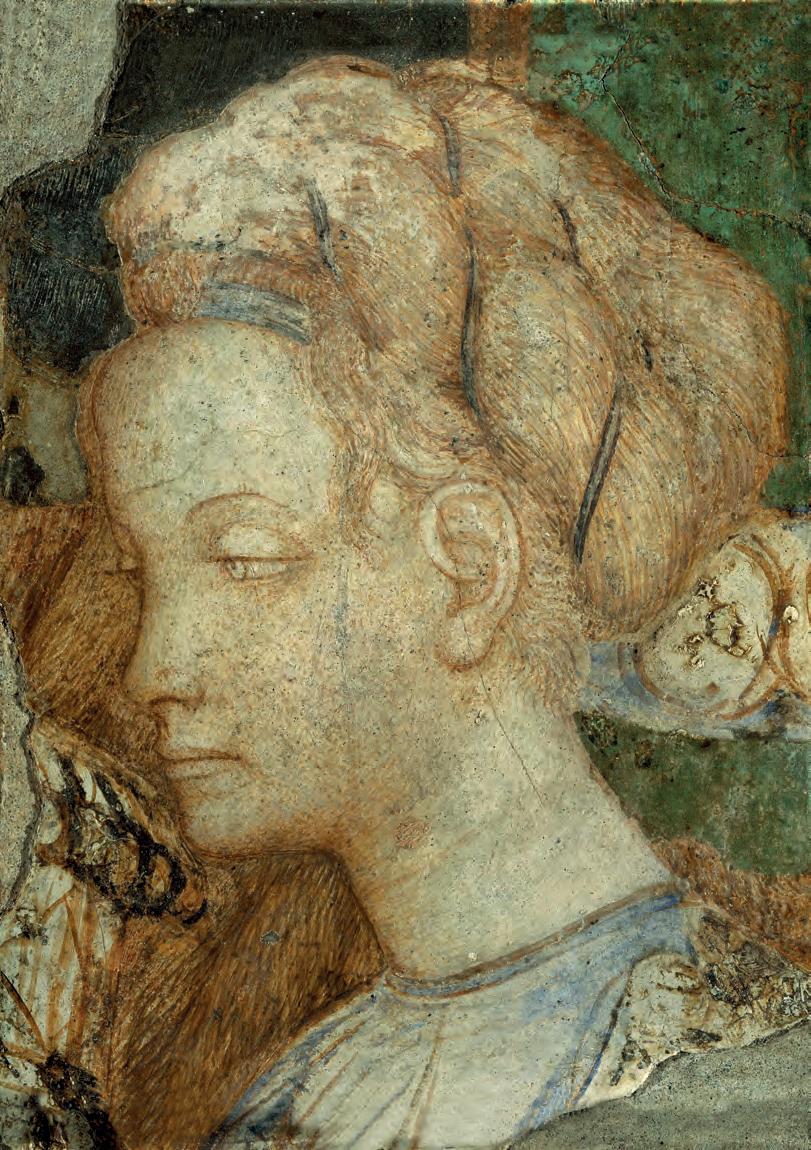

the compositional and chromatic similarities.41 The lower painting shares striking similarities with another portrait by Pontormo which is generally held to depict Cosimo I de’ Medici, Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici (Fig.21). There is a noted correspondence of the overall design, the contour of the sitter’s shoulders, and aspect of the head and facial features, and most compellingly, the lower pair of hands, though Bronzino places them further to the left. These comparisons suggest that Bronzino may have had this particular portrait by Pontormo in mind in his first conception sketched on the Sydney panel.

Given Bronzino’s well-documented propensity for radically reshaping his compositions, one can only speculate on what form the final image might have taken had it been completed. The overpainted figure – with his seated pose, black garb, book in hand and frontal gaze, set against a pale neutral background – may be placed between Bronzino’s early compositions still influenced by Pontormo and a later painting of an unidentified sitter, Portrait of a young man (Fig.24).42 The similarity of the overall composition and the sitter’s dress as well as the facial likenesses are compelling.

A rare drawing by Bronzino, Head of a man (Fig.22), which has been identified as being a study for the Nelson-Atkins Portrait of a young man, was digitally rescaled and layered with a tracing of the face of Sydney lower painting (Fig.23).43 The degree of alignment of the facial features is remarkable, with the rounded eyes and the contours of the face matching almost exactly. Furthermore, the soft hat and black cloak, the overall posture of the sitter, the shape of the outer contour of his shoulders as well as the position of his right hand suggest a close proximity between the two compositions (see Fig.24). Any direct relation to the Nelson-Atkins Portrait of a young man and the Getty drawing is complicated, however, by the fact that the unfinished Sydney portrait was carried out at least five years before the accepted date (c.1550–55) of the Nelson-Atkins portrait.

Details of the development of the Nelson-Atkins portrait were revealed by a thorough technical study conducted in the early 1990s.44 In an intriguing reversal of the sequence discovered on the Sydney panel, the study showed that the young man portrayed in a cloak had been initially conceived wearing armour. The sitter’s left hand was initially absent, hidden behind an ovoid shield with the right hand resting on something, possibly a helmet. The sitter then underwent a radical change of costume, exchanging the armour for a doublet, and finally the cloak and hat, which are similar to those worn by the subject of the lower Sydney painting. The Nelson-Atkins young man’s hands hold a sword, while the Sydney sitter rests his lower right hand on something not apparent or not depicted. Bronzino’s capacity to radically transform a single work from a figure in armour to one in a cloak and hat, as revealed by the examination of the Nelson-Atkins portrait, is interesting to keep in mind when considering the Sydney panel. The hidden portrait mapped

21. Portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici, half-length, in a black slashed doublet and a plumed hat, holding a book, by Jacopo Pontormo. c.1537–38. Oil (or oil and tempera) on panel, 100.6 by 77 cm. (Private collection; Bridgeman Images). 22. Head of a man, by Agnolo Bronzino. c.1550–55. Black chalk on paper, 13.8 by 10.3 cm. (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles).

Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour

23. Fig.22 superimposed on the face of the Sydney lower painting red line trace in Fig.20. (Photograph © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives). 24. Portrait of a young man, by Agnolo Bronzino. 1550–55. Oil on panel, 85.73 by 68.58 cm. (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City), and Fig.20 superimposed. (Photograph © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives). at the Synchrotron is of sufficient clarity to reveal the dynamic working method inherent in Bronzino’s creative process. The multiple hands along with the variations in the face also support Simon’s identification of two conceptions of a single portrait in progress.

If the likeness to Cosimo is accepted, the lower painting could be read as a preceding attempted portrait of the duke as an elegant gentleman and scholar rather than a warrior. If this concept was then rejected by Bronzino for a more forceful depiction of the duke in armour, in greater accord with the requirements for ‘a man capable of battle but triumphing through peaceful means’, the latter was originated on a new panel, the portrait in the Uffizi.45 Alternatively, it is possible that the lower Sydney painting is the development of an unrelated portrait of a young Florentine nobleman, whose identity is currently unknown. This initial attempt was eventually abandoned, and the panel was instead used to expand the primary half-length Uffizi composition to create the primary three-quarter-length version of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour. If the lapse of time between the execution of the two portraits of the Sydney panel is still unclear, the similar chemical composition of the azurite used in the background of both suggests some proximity. However, the resemblance of the lower Sydney painting to the Nelson-Atkins Portrait of a young man – the similarity of the composition and the apparent use of the Getty drawing as the basis for the sitter’s face in both cases as well as the comparable neutral coloured background – suggests that the two paintings are related. It is possible, therefore, that the Nelson-Atkins panel represents the completion of the abandoned portrait, which was not, therefore, a depiction of Cosimo.46

Although ultimately not carried out, the decision to reduce the three-quarter-length format may have been a response to Cosimo’s preference for a replica without additional inventions, as in the case of the replica altarpiece for Eleonora di Toledo’s chapel. Or perhaps Bronzino was unsatisfied with the extended composition, because either of its awkward placement of the hips, necessitated by a need to show the broncone attached to the tree trunk, or the overall composition being squeezed into a less than ideal pre-determined size. These modifications have been revealed as artistic deliberations rather than simple copying errors and they indicate an original composition that was worked on by the master. In undertaking the portrait of the young duke using the format of a panel that had already been partially painted, Bronzino achieved an enduring archetype, the most successful portrait of the recently appointed ruler of Florence.

41 Other indications of Bronzino’s early style, such as an architectural background, are, however, absent. 42 Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, inv. no.49-28, oil on panel, 85.7 by 68.6 cm. 43 J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv. no.90.GB.29, black chalk on paper, 13.8 by 10.3 cm. On this drawing and its link to the Nelson-Atkins painting, see C.C. Bambach et al.: exh. cat. The Drawings of Bronzino, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2010, pp.204–05, no.54. 44 See Rowlands, op. cit. (note 22), pp.181–88, no.22. 45 Simon, op. cit. (note 5), p.535. 46 Since the submission of the present article, a further attempt has been made to identify the sitter of the Nelson-Atkins portrait. In K. Christiansen and C. Falciani, eds: exh. cat. The Medici, Portraits and Politics 1512–1570, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2021, pp.256–57, the authors propose to identify the sitter with Francesco Guadagni, a young nobleman descendant of the newly established Florentine branch of the Guadagni family, and the rising son of one of Bronzino’s important patrons. This identification would consolidate the hypothesis of the sitter’s Sydney lower painting as a young aristocrat representative of the new Florentine society.

Bronzino’s portrait of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour

23. Fig.22 superimposed on the face of the Sydney lower painting red line trace in Fig.20. (Photograph © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives). 24. Portrait of a young man, by Agnolo Bronzino. 1550–55. Oil on panel, 85.73 by 68.58 cm. (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City), and Fig.20 superimposed. (Photograph © Art Gallery of New South Wales, Simon Ives). at the Synchrotron is of sufficient clarity to reveal the dynamic working method inherent in Bronzino’s creative process. The multiple hands along with the variations in the face also support Simon’s identification of two conceptions of a single portrait in progress.

If the likeness to Cosimo is accepted, the lower painting could be read as a preceding attempted portrait of the duke as an elegant gentleman and scholar rather than a warrior. If this concept was then rejected by Bronzino for a more forceful depiction of the duke in armour, in greater accord with the requirements for ‘a man capable of battle but triumphing through peaceful means’, the latter was originated on a new panel, the portrait in the Uffizi.45 Alternatively, it is possible that the lower Sydney painting is the development of an unrelated portrait of a young Florentine nobleman, whose identity is currently unknown. This initial attempt was eventually abandoned, and the panel was instead used to expand the primary half-length Uffizi composition to create the primary three-quarter-length version of Cosimo I de’ Medici in armour. If the lapse of time between the execution of the two portraits of the Sydney panel is still unclear, the similar chemical composition of the azurite used in the background of both suggests some proximity. However, the resemblance of the lower Sydney painting to the Nelson-Atkins Portrait of a young man – the similarity of the composition and the apparent use of the Getty drawing as the basis for the sitter’s face in both cases as well as the comparable neutral coloured background – suggests that the two paintings are related. It is possible, therefore, that the Nelson-Atkins panel represents the completion of the abandoned portrait, which was not, therefore, a depiction of Cosimo.46

Although ultimately not carried out, the decision to reduce the three-quarter-length format may have been a response to Cosimo’s preference for a replica without additional inventions, as in the case of the replica altarpiece for Eleonora di Toledo’s chapel. Or perhaps Bronzino was unsatisfied with the extended composition, because either of its awkward placement of the hips, necessitated by a need to show the broncone attached to the tree trunk, or the overall composition being squeezed into a less than ideal pre-determined size. These modifications have been revealed as artistic deliberations rather than simple copying errors and they indicate an original composition that was worked on by the master. In undertaking the portrait of the young duke using the format of a panel that had already been partially painted, Bronzino achieved an enduring archetype, the most successful portrait of the recently appointed ruler of Florence.

41 Other indications of Bronzino’s early style, such as an architectural background, are, however, absent. 42 Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, inv. no.49-28, oil on panel, 85.7 by 68.6 cm. 43 J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv. no.90.GB.29, black chalk on paper, 13.8 by 10.3 cm. On this drawing and its link to the Nelson-Atkins painting, see C.C. Bambach et al.: exh. cat. The Drawings of Bronzino, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2010, pp.204–05, no.54. 44 See Rowlands, op. cit. (note 22), pp.181–88, no.22. 45 Simon, op. cit. (note 5), p.535. 46 Since the submission of the present article, a further attempt has been made to identify the sitter of the Nelson-Atkins portrait. In K. Christiansen and C. Falciani, eds: exh. cat. The Medici, Portraits and Politics 1512–1570, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2021, pp.256–57, the authors propose to identify the sitter with Francesco Guadagni, a young nobleman descendant of the newly established Florentine branch of the Guadagni family, and the rising son of one of Bronzino’s important patrons. This identification would consolidate the hypothesis of the sitter’s Sydney lower painting as a young aristocrat representative of the new Florentine society.

focus on bronzino

Bronzino’s ‘Petrarch’ retrieved: new light on Bartolomeo Bettini’s ‘camera’

In about 1531 Bronzino was commissioned by the banker Bartolomeo Bettini to paint portraits of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio for a room in his house in Florence. All were believed lost until the rediscovery in 2002 of the ‘Dante’. A painting of Petrarch is here identified as a record of Bronzino’s composition and it is argued that an anonymous painting of Boccaccio may be derived from the third of Bettini’s portraits.

by jeroen stumpel

In 1941 the italian journal L’Arte published black-and-white photographs of a pair of oval paintings in a private collection in Italy that were described as portraits of Dante Alighieri and Petrarch by Pontormo (Figs.1 and 2). There are more recent colour photographs of them in the Fondazione Federico Zeri, Bologna (Figs.4 and 5), where the paintings are attributed to Giovanbattista Naldini (c.1535–91).1 This may well be correct, but the source of the compositions is almost certainly Agnolo Bronzino (1503–72). In 2002 a larger painting of Dante by Bronzino, which is obviously the prototype for the oval portrait of the poet, was discovered in an Italian private collection and published by Philippe Costamagna (Fig.3).2 The close correspondence between the two paintings makes it more than likely that the oval pendant of Petrarch also derived from a composition by Bronzino. It will be argued here that this can be confirmed by an intriguing picture in an Italian private collection, published here for the first time (Fig.8), the composition of which clearly seems to be the model

1 and 2. Portraits of Dante and Petrarch published as works by Pontormo. (From L’arte, November 1941, pp.xvii and xix).

for the oval version. Its discovery also sheds new light on the series of paintings to which Bronzino’s Dante originally belonged.

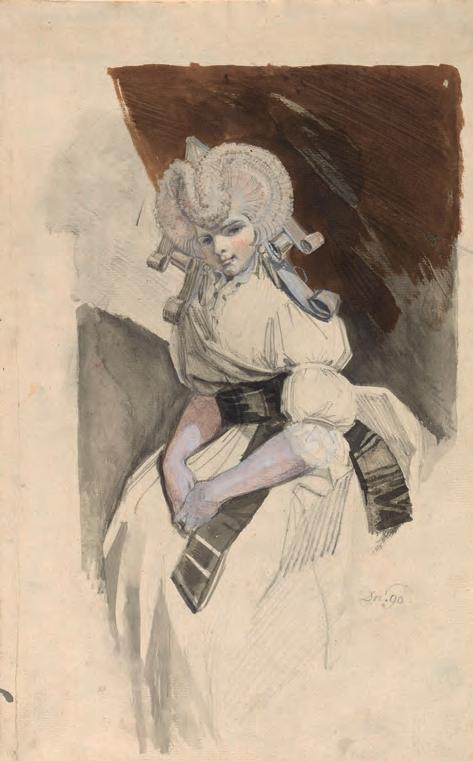

The painting, which is on canvas, depicts Petrarch, half-length, seen from a low viewpoint. Crowned with a poet’s laurel wreath, he is dressed in a manner familiar from images of Petrarch from the fourteenth century onwards, with a cap and cape to denote he had taken minor orders and acquired a canonical bene ce.3 The head, parts of which are beautifully painted, clearly surpasses the oval in quality and mood (Figs.6 and 7). Discussion of the authorship of the painting is however hampered by its less than pristine condition. No de nitive judgment can be made until it is cleaned and a technical examination can be made, but the present owners are reluctant to embark on such initiatives. There are compelling reasons, however, to argue that at the very least the painting records an important composition by the young Bronzino that was hitherto known only from references to it in the sixteenth century.

Two well-known passages in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives relate the circumstances of how in about 1531 Bronzino was commissioned to paint these portraits. Having returned to Florence from Pesaro, where he had painted ‘a number of gures in oils on the spandrels of a vault’ in the Villa

The author is much indebted to the Dutch University Institute for Art History (NIKI) in Florence for the opportunity to conduct this research. 1 The reproductions in L’Arte are mentioned (not reproduced) in J.K. Nelson: ‘Dante portraits in sixteenthcentury Florence’, Gazette des BeauxArts 120 (1992), pp.64–71. According to the information accompanying the photographs in the Fondazione Federico Zeri, the paintings were formerly in the collection of Marchese G. Capponi, Florence, and were subsequently off ered at the Mercato Antiquario, Milan, in 1970. The author is very grateful to Sanne Wellen for informing him about the presence of these 3. Allegorical portrait of Dante, by Agnolo Bronzino. c.1532. Oil on canvas, 130 by 136 cm. (Private collection).

photographs in the Fondazione Federico Zeri. 2 P. Costamagna: ‘De l’idéal de beauté aux problèmes d’attribution: vingt ans de recherché sur le portrait fl orentin au XVIe siècle’, Studiolo, revue d’histoire de l’art de l’académie de France à Rome 1 (2002), pp.193–220, at pp.208–09. 3 For the iconography of Petrarch’s portraits, see, for example, S. Pinto: ‘Petrarca nel tempo’ in E. Bordignon Favero, ed.: Per Maria Cionini Visani: scritti di amici, Florence 1977, pp.143–46; and C.B. Strehlke: exh. cat. Pontormo, Bronzino and the Medici: The Transformation of the Renaissance Portrait in Florence, Philadelphia (Museum of Art) 2004.

4. Dante Alighieri, attributed to Giovanbattista Naldini. 1550–1600. Oil on panel. (Photograph Fondazione Federico Zeri, Bologna). 5. Petrarch, attributed to Giovanbattista Naldini. 1550–1600. Oil on panel. (Photograph Fondazione Federico Zeri, Bologna). 6. Detail of Fig.8, showing Petrarch’s face. 7. Detail of Fig.5, showing Petrarch’s face. Opposite 8. Allegorical portrait of Petrarch, here attributed to a follower of Bronzino. c.1550? Oil on canvas, 110.6 by 124 cm. (Private collection).

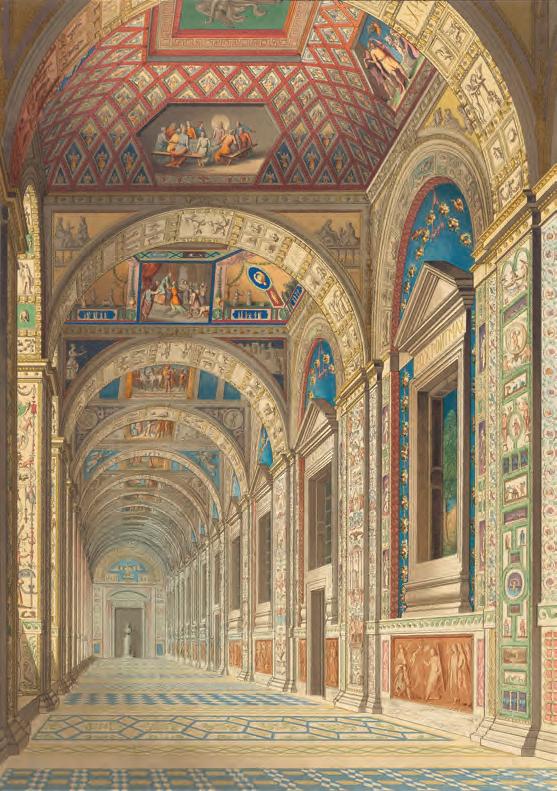

Imperiale,4 he was asked by the banker Bartolomeo Bettini to undertake a similar commission by painting ‘certain lunettes in a chamber, the portraits of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, half-length figures of great beauty’.5 In the next sentence Vasari tells us that Bronzino, ‘having finished these paintings’, engaged to make a number of other portraits for different patrons. That he produced at least three paintings for Bettini is confirmed by a passage in Vasari’s Life of Pontormo in which it is recorded that Michelangelo, who was Bettini’s ‘suo amicissimo’ (‘most dear friend’)

made for him a cartoon of a nude Venus with a Cupid who is kissing her, in order that he might have it executed in painting by Pontormo and place it in the centre of a chamber of his own, in the lunettes of which he had begun to have painted by Bronzino figures of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio, with the intention of having there all the other poets who have sung of love in Tuscan prose and verse.6

4 ‘Lavorò anche all’Imperiale, villa del detto duca [Guidobaldo della Rovere], alcune figure a olio ne’peducci d’una volta’. They are in the so-called Sala dei Semibusti (where they remain); see G. Vasari: Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori scultori ed architettori, ed. G. Milanesi, Florence 1878–85, VII, p.595. 5 ‘i quali quadri finiti, ritrasse Bonacorso Pinadori’, ibid., pp.291–95. 6 ‘che il Buonarotti suo amicissimo gli fece un cartone d’una Venere ignuda con un Cupido che la bacia, per farla fare di pittura al Pontormo, e metterla in mezzo a una sua camera, nelle lunette della quale aveva cominciato a fare dipignere dal Bronzino, Dante, Petrarca e Boccaccio, con animo di farvi gli altri poeti che hanno con versi e prose toscane cantato d’Amore’, ibid., VI, p.277, transl. G.C. Du Vere: The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, London 1912–15, repr. New York 1976. For an attempt at a reconstruction of the camera, see R. Compton: ‘“Omnia vincit amor”: the sovereignty of love in Tuscan poetry and Michelangelo’s Venus and Cupid’, Mediaevalia 22 (2012), pp.229–60. For an excellent essay on Bettini, see R. Aste: ‘Bartolomeo Bettini e la decorazione della sua “camera” fiorentina / Bartolomeo Bettini and his Florentine “chamber” decoration’, in F. Falletti and J. Katz Nelson, eds: exh. cat. Venere e Amore: Michelangelo e la nuova belleza ideale / Venus and Love: Michelangelo and the New Ideal of Beauty, Florence (Galleria dell’Accademia) 2002, as well as the more extensive treatment in R. Aste: ‘A merchant-banker’s ascent by design: Bartolomeo Bettini’s cycle of paintings by Michelangelo, Pontormo, and Bronzino for his Florentine camera’, unpublished PhD thesis (City University of New York, 2015), available at www. academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/841, accessed 2nd December 2022; this includes a full bibliography concerning the camera.

This painting by Pontormo is generally identified as the Venus and Cupid in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence (Fig.10).

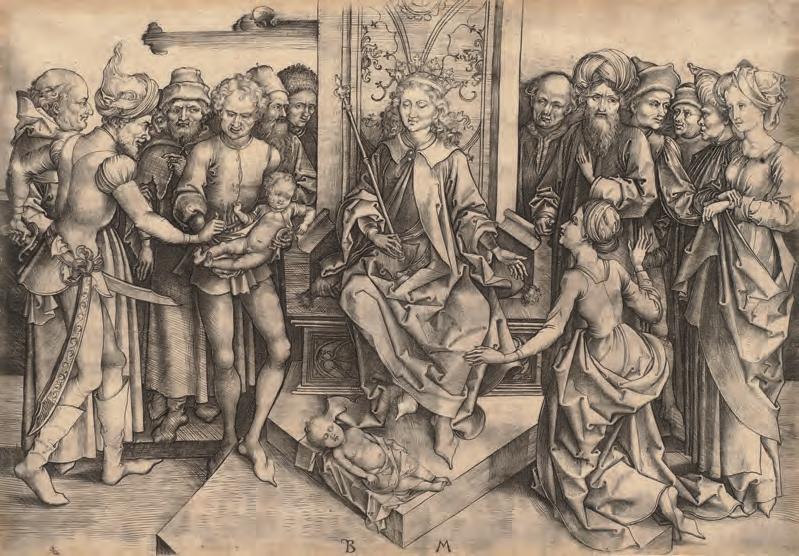

The portraits of the poets painted by Bronzino for Bettini were all considered lost until Costamagna’s discovery of the portrait of Dante.7 The composition was already known from a replica in the National Gallery of Art, Washington (Fig.9), which is believed to date from the sixteenth century, and may perhaps have been painted by Bronzino or his workshop. It lacks the rounded top of the original, which is related to the lunette for which it was painted, and is on panel whereas the original is on canvas. In the composition, Dante looks away from the viewer, while

9. Allegorical portrait of Dante, by the workshop of Bronzino. 1 550–1600? Oil on panel, 126.9 by 120 cm. (National Gallery of Art, Washington). 10. Venus and Cupid, by Jacopo Pontormo, based on a cartoon by Michelangelo. c.1532–33. Oil on panel, 194 by 128 cm. (Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence; Bridgeman Images). 11. Detail of Fig.6, probably showing Petrarch’s house in the Vaucluse. 12. Detail of Fig.6, showing a lira da braccio tied to a laurel tree. 13. Detail of Fig.6, showing Petrarch holding an open book.

the open book in his hand legibly shows a large part of the opening of Canto 25 of the Paradiso. The correspondence with the newly discovered Petrarch composition is striking. Pose, proportion, mood and viewpoint are all similar. Petrarch also holds an open book, on which is written in an elegant script poem number 304 from the Canzoniere (also known as sonnet number 263). As in the Dante portrait, the atmosphere is rather dark and there is a distant landscape in dusk. In both portraits a single building is visible in the background, tiny because of its distance. In the Dante it is the cupola of Florence Cathedral. In the Petrarch it is probably the poet’s famous small house in the Vaucluse, lovingly described by him both in his letters and in the Canzoniere (Fig.11). It was there that he wrote much of his poetry and famously planted laurels as a tribute to his beloved Laura.8 Although the quotation from the Paradiso in the Dante portrait is damaged, enough is visible to establish that the script is practically identical to that of the poem in the portrait of Petrarch.9

The Petrarch commission came rather early in Bronzino’s development as a painter, when he was about twenty-eight years old. Yet the painting, even though it is likely to be a copy, seems to incorporate in a mature form distinctive traits of the artist’s long career. The rendering of the face, for example, with soft and careful transitions of flesh tones from the shadowed parts to the rosy cheeks, includes a subtle spot of light on the lower jaw, apparently a diffused reflection from the poet’s white gown. This subtly painted, finely draped gown is reminiscent of the depictions of comparable refined folds in Bronzino’s Portrait of a lady with a dog (c.1532–33; Städel Museum, Frankfurt), or the famous Laura Battiferri (1552; Palazzo Vecchio, Florence). The elongated hands and the emphatic foreshortening of the left arm are equally Bronzinesque, as are the partially closed – almost drooping – lids and the way the meeting of the delicately painted lips is indicated with a surprisingly emphatic black line.

The inclusion of an open book with text that is rendered in almost pedantic detail, as in the Dante portrait, indicates that this may have been a central motif in the series of portraits for Bettini. An early Florentine

9. Allegorical portrait of Dante, by the workshop of Bronzino. 1550–1600? Oil on panel, 126.9 by 120 cm. (National Gallery of Art, Washington). 10. Venus and Cupid, by Jacopo Pontormo, based on a cartoon by Michelangelo. c.1532–33. Oil on panel, 194 by 128 cm. (Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence; Bridgeman Images). 11. Detail of Fig.6, probably showing Petrarch’s house in the Vaucluse. 12. Detail of Fig.6, showing a lira da braccio tied to a laurel tree. 13. Detail of Fig.6, showing Petrarch holding an open book.

the open book in his hand legibly shows a large part of the opening of Canto 25 of the Paradiso. The correspondence with the newly discovered Petrarch composition is striking. Pose, proportion, mood and viewpoint are all similar. Petrarch also holds an open book, on which is written in an elegant script poem number 304 from the Canzoniere (also known as sonnet number 263). As in the Dante portrait, the atmosphere is rather dark and there is a distant landscape in dusk. In both portraits a single building is visible in the background, tiny because of its distance. In the Dante it is the cupola of Florence Cathedral. In the Petrarch it is probably the poet’s famous small house in the Vaucluse, lovingly described by him both in his letters and in the Canzoniere (Fig.11). It was there that he wrote much of his poetry and famously planted laurels as a tribute to his beloved Laura.8 Although the quotation from the Paradiso in the Dante portrait is damaged, enough is visible to establish that the script is practically identical to that of the poem in the portrait of Petrarch.9

The Petrarch commission came rather early in Bronzino’s development as a painter, when he was about twenty-eight years old. Yet the painting, even though it is likely to be a copy, seems to incorporate in a mature form distinctive traits of the artist’s long career. The rendering of the face, for example, with soft and careful transitions of flesh tones from the shadowed parts to the rosy cheeks, includes a subtle spot of light on the lower jaw, apparently a diffused reflection from the poet’s white gown. This subtly painted, finely draped gown is reminiscent of the depictions of comparable refined folds in Bronzino’s Portrait of a lady with a dog (c.1532–33; Städel Museum, Frankfurt), or the famous Laura Battiferri (1552; Palazzo Vecchio, Florence). The elongated hands and the emphatic foreshortening of the left arm are equally Bronzinesque, as are the partially closed – almost drooping – lids and the way the meeting of the delicately painted lips is indicated with a surprisingly emphatic black line.

The inclusion of an open book with text that is rendered in almost pedantic detail, as in the Dante portrait, indicates that this may have been a central motif in the series of portraits for Bettini. An early Florentine

14. Proposed reconstruction of original placement of Figs.3 and 8. 15. Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus, by Agnolo Bronzino. c.1537–39. Oil on canvas, 93.7 by 76.4 cm. (Philadelphia Museum of Art; Bridgeman Images).

example of such a device is a portrait attributed to Andrea del Sarto of a young woman holding an open book in which poems by Petrarch are legible (1528; Gallerie degli U zi, Florence). This motif recurs most emphatically, however, in works by Bronzino. From at least his portrait of Lorenzo Lenzi onwards (1528; Castello Sforzesco, Milan), books and booklets, both with or without legible texts, are a distinctive feature of his portraits, such as Ugolino Martelli (c.1535; Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), Lucrezia Panciatichi (1545; U zi, Florence) and Laura Battiferri. The motif became, one might argue, a vehicle par excellence of orentinità in Bronzino’s portraits of living people, but it had already been fully explored in the ctive portraits for Bettini.

The portrait of Petrarch has clearly been lined in the not-too-distant past and so it is possible that the canvas was not its original support. It is, however, notable that the original Dante portrait is also on canvas, which Bronzino used relatively rarely, and the comparable decorative sequence he painted for the Villa Imperiale at Pesaro is also on canvas. The original Dante is about ten centimetres wider than the Petrarch, but the latter looks as though it has been cut on both sides. The cropped elbow seems unnatural, as does the way the book is missing a small part on the left. A hypothetical addition of the ends of the book and of the elbow brings the painting very close in size to the original Dante painting. If a lunette comparable to that of the Dante is added to the top the result is a tentative but convincing pendant (Fig.14). Cleaning and thorough technical examination of the Petrarch might reveal whether it has been trimmed and whether traces of a lunette top remain.

The iconography of Petrarch has been well researched.10 The composition presented here appears to be richer in allegorical allusions than the great majority of the portraits of the poet. Behind Petrarch for instance, there is a string instrument and its bow, which are tied to a laurel tree by means of a reddish ribbon (Fig.12). This is a lira da braccio, an antecedent of the violin, used for accompanying singing during the fteenth and sixteenth centuries.11 It appears in a number of paintings of the time, such as Dosso Dossi’s Apollo and Daphne (1524; Galleria Borghese,

7 Costamagna, op. cit. (note 2). See entry by R. de Giorgi in C. Falciani and A. Natali, eds: exh cat. Bronzino:Painter and Poet at the Court of the Medici, Florence (Palazzo Strozzi) 2010–11, p.206. See also A. Natali, ed.: . . .Con altra voce ritornerò poeta: il ritratto di Dante del Bronzino alla Certosa di Firenze / The Portrait of Dante by Bronzino at the Certosa of Florence, Florence 2020; and the entry by J. Siemon in K. Christiansen and C. Falciani, eds: exh. cat. The Medici, Portraits and Politics, 1512–1517, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2021, pp.164–66. 8 For a thorough discussion of the reputation of this house and other lieux de mémoire of Petrarch, see J.B. Trapp: ‘Petrarchan places: an essay in the iconography of commemoration’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 69 (2006), pp.1–50. 9 In the Petrarch painting the letters seem to have been partly but accurately restored. For a fi ne essay with reference to the use of writing in the work of Bronzino and his circle, see E. Cropper: ‘Pontormo and Bronzino in Philadelphia: a double portrait’, in Strehlke, op. cit. (note 3), pp.1–34 and pp.67–69, entries for cat. nos.6 and 7. 10 See, most recently, R. Speck and F. Neumann, eds: Klug und von hehrer Gestalt: Petrarca Bildnisse aus sieben Jahrhunderten, Cologne 2018. 11 For the lira da braccio, see A. Hajdecki: Die italienische Lira da Braccio: eine kunsthistorische Studie zur Geschichte der Violine, Mostar 1892, repr. Amsterdam 1965; and S. Scott Jones: The Lira de Braccio, Bloomington 1995. The well-known treatise M. Praetorius: Syntagma Musicum Theatrum Instrumentorum seu Sciagraphia, I–III, Wittenberg and Wolfenbüttel 1614–20, makes it clear that the bow used for the lira da braccio corresponds exactly to the bow hanging from the laurel stem in the Petrarch painting, see ibid.: II (‘De Organographia’), no.XX.