12 minute read

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England by elizabeth goldring

The many faces of Mary Magdalene

herself. A corrective should also be added to Giannini’s otherwise excellent catalogue entry for this painting: Michael Hirst explicitly rejected William Wallace’s su estion that Christ ‘follows with his look his own hands and nger while these seem to touch [her] protuberant breast’ on the grounds that it contradicted the underlying sense of the subject.6

Advertisement

Acidini speculates that Mary Magdalene’s mantle in Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo’s dramatic half-length Mary Magdalene of 1535–40 in the National Gallery, London – a di erent version was shown in the exhibition (1535–40; Gallerie degli U zi; no.6.33) – might be the shroud retrieved from the empty tomb after the Resurrection, providing the saint with the close bodily contact denied to her by the risen Christ. This hypothesis is problematic for a number of reasons; to begin with, the mantle is of silk and not a linen grave cloth. The author does not mention that it is wrapped around her hand and held to her cheek in a standard Classical mourning gesture. Most importantly, Mary Magdalene’s visit to the empty tomb takes place before the Noli me tangere scene and so Christ’s touch had not yet been denied to her.

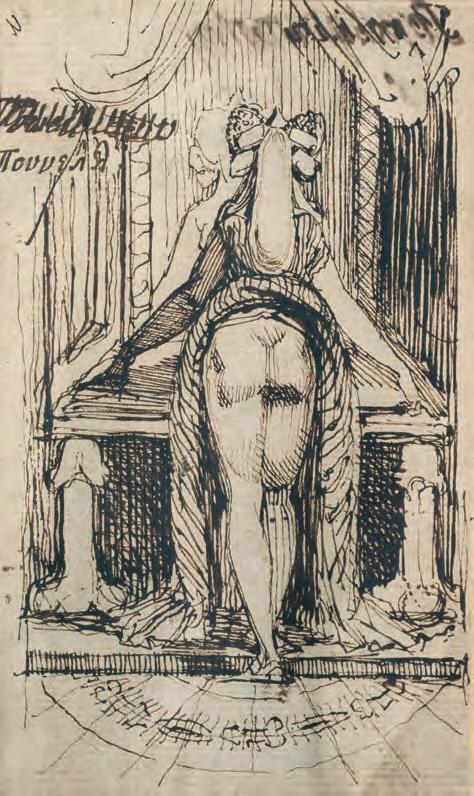

Acidini concludes with the way that Mary Magdalene was transformed into a worldly bella penitente in the courts of northern Italy, her nudity no longer hidden by hair, but exposed in ‘generous fullness’ (p.108) by Lombard followers of Leonardo, such as Giampetrino, who were in uenced by his lost StandingLeda and Kneeling Leda. This development led ultimately to Corre io and Titian, a theme taken up in later essays. In Francesco De Carolis’s catalogue entry for Mariotto di Nardo’s panel of the Trinity with the Virgin and Mary Magdalene (1400–05; Museo della Basilica di S. Maria delle Grazie, San Giovanni Val d’Arno; no.5.12), the Magdalene’s scarlet garments are interpreted as a reference to ‘her sinful condition’ (p.450); the author is unaware that recent work on the colour symbolism of Mary Magdalene has demonstrated that her wearing scarlet relates to the Passion and to caritas, the Christian love of humankind, and faith, not to ‘donne traviate’ (p.99).7

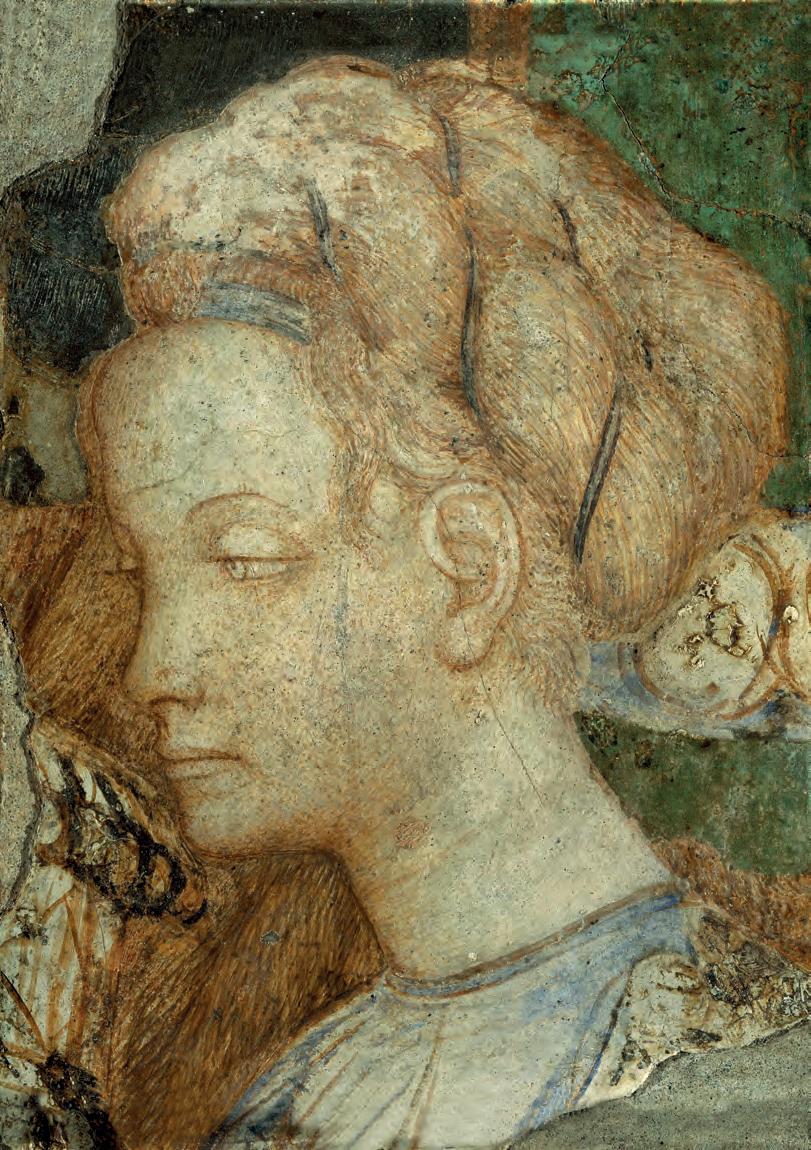

Virna Ravaglia provides an excellent contextual discussion of the Lamentation groups from late fteenth-century Emilia Romagna. She quotes Gabriele D’Annunzio’s description of Mary Magdalene in Niccolo dell’Arca’s polychrome terracotta group in Bologna (p.115, g.1), as a ‘howl turned to stone’ (‘l’urlo pietri cato’; p.119). The gures in such ensembles are extraordinarily life-like, as demonstrated by Guido Mazzoni’s groups, one of which (no.1.10; Fig.3), formed the dramatic focal point of the exhibition’s rst gallery, in the nave of the church. The wonderfully remorseful Magdalene gures in paintings of the supper in the house of the phariseeby Girolamo Romanino (1545; S. Giovanni Evangelista, Brescia; no.6.9) and Moretto da Brescia (no.6.10; Fig.5) are excellentlytreated in Massimo Francucci’s catalogue entries; the paintings were displayed alongside each other in the exhibition to striking e ect. In Moretto’s image of beautiful feminine sorrow, the light falls on the rippling hair of Mary Magdalene, who wears a pleated green satin gown, a white and gold striped scarf and ochre gold mantle. Her left hand tenderly caresses Christ’s foot and her right holds her hair draped over it; her jar of ointment is placed on the ground next to her. The still lifes of bread and wine, prominent on the tables above Mary Magdalene, possess eucharistic symbolism. These works acted as a prelude to paintings in the same room of the repentant Magdalene in the grotto into which she withdrew, by such artists as Titian, Domenico Tintoretto and Bernardo Strozzi.

An essay by Sonia Cavicchiolo explores the way that the depiction of Mary Magdalene changed in the Baroque period, starting with Carava io’s penitent (c.1596–97; Galleria Doria Pamphilj) and Rubens’s weeping gure at the foot of the Cross (1617–19; Musée du Louvre). These gures re ect the saint’s post-Tridentine paradigmatic role as an embodiment of penance in the light of the Church of Rome’s stance on the sacraments, which had been challenged by the Protestants. In Guido Cagnacci’s Conversion of Mary Magdalene (1661; Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena), the semi-nude saint is chastised by her sister Martha, whereas paintings by Georges de la Tour – for example that of c.1640 in the National Gallery of Art, Washington – and Domenico Fetti (c.1617; Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome) show her meditating with a skull and book. The exhibition included works by Cagnacci (no.7.28; Fig.7), Alessandro Rosi (c.1670; Gallerie degli U zi; no.7.29) and Simon Vouet (1649; Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon; no.7.30) showing the bare-breasted saint in a state of spiritual ravishment, or ecstasy, which according to Ignatius of Loyola, was the ultimate aim of meditation, the reunion of the soul with God. Francesco Furini’s penitent Magdalene (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), painted c.1633, the year that the artist was ordained, shows the saint naked, except for a strategically placed strand of hair. Cavicchiolo describes her as a ‘sinuous nude’ whose ‘eroticism is revealing and disturbing’ (p.131).

5. Supper in the house of the pharisee, by Moretto da Brescia. 1550–54. Oil on canvas, 207 by 140 cm. (S. Maria in Calchera, Brescia; Bridgeman Images).

6 M. Hirst: Tre Saggi su Michelangelo, Florence 2004, p.22; and W.E. Wallace: ‘Il “Noli me Tangere” di Michelangelo: tra sacro e profano’, Arte Cristiana 76 (1988), pp.443–50, at p.448. 7 See S. Haskins: ‘Foreword’, in M.A.

The many faces of Mary Magdalene

herself. A corrective should also be added to Giannini’s otherwise excellent catalogue entry for this painting: Michael Hirst explicitly rejected William Wallace’s su estion that Christ ‘follows with his look his own hands and nger while these seem to touch [her] protuberant breast’ on the grounds that it contradicted the underlying sense of the subject.6

Acidini speculates that Mary Magdalene’s mantle in Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo’s dramatic half-length Mary Magdalene of 1535–40 in the National Gallery, London – a di erent version was shown in the exhibition (1535–40; Gallerie degli U zi; no.6.33) – might be the shroud retrieved from the empty tomb after the Resurrection, providing the saint with the close bodily contact denied to her by the risen Christ. This hypothesis is problematic for a number of reasons; to begin with, the mantle is of silk and not a linen grave cloth. The author does not mention that it is wrapped around her hand and held to her cheek in a standard Classical mourning gesture. Most importantly, Mary Magdalene’s visit to the empty tomb takes place before the Noli me tangere scene and so Christ’s touch had not yet been denied to her.

Acidini concludes with the way that Mary Magdalene was transformed into a worldly bella penitente in the courts of northern Italy, her nudity no longer hidden by hair, but exposed in ‘generous fullness’ (p.108) by Lombard followers of Leonardo, such as Giampetrino, who were in uenced by his lost StandingLeda and Kneeling Leda. This development led ultimately to Corre io and Titian, a theme taken up in later essays. In Francesco De Carolis’s catalogue entry for Mariotto di Nardo’s panel of the Trinity with the Virgin and Mary Magdalene (1400–05; Museo della Basilica di S. Maria delle Grazie, San Giovanni Val d’Arno; no.5.12), the Magdalene’s scarlet garments are interpreted as a reference to ‘her sinful condition’ (p.450); the author is unaware that recent work on the colour symbolism of Mary Magdalene has demonstrated that her wearing scarlet relates to the Passion and to caritas, the Christian love of humankind, and faith, not to ‘donne traviate’ (p.99).7

Virna Ravaglia provides an excellent contextual discussion of the Lamentation groups from late fteenth-century Emilia Romagna. She quotes Gabriele D’Annunzio’s description of Mary Magdalene in Niccolo dell’Arca’s polychrome terracotta group in Bologna (p.115, g.1), as a ‘howl turned to stone’ (‘l’urlo pietri cato’; p.119). The gures in such ensembles are extraordinarily life-like, as demonstrated by Guido Mazzoni’s groups, one of which (no.1.10; Fig.3), formed the dramatic focal point of the exhibition’s rst gallery, in the nave of the church. The wonderfully remorseful Magdalene gures in paintings of the supper in the house of the phariseeby Girolamo Romanino (1545; S. Giovanni Evangelista, Brescia; no.6.9) and Moretto da Brescia (no.6.10; Fig.5) are excellentlytreated in Massimo Francucci’s catalogue entries; the paintings were displayed alongside each other in the exhibition to striking e ect. In Moretto’s image of beautiful feminine sorrow, the light falls on the rippling hair of Mary Magdalene, who wears a pleated green satin gown, a white and gold striped scarf and ochre gold mantle. Her left hand tenderly caresses Christ’s foot and her right holds her hair draped over it; her jar of ointment is placed on the ground next to her. The still lifes of bread and wine, prominent on the tables above Mary Magdalene, possess eucharistic symbolism. These works acted as a prelude to paintings in the same room of the repentant Magdalene in the grotto into which she withdrew, by such artists as Titian, Domenico Tintoretto and Bernardo Strozzi.

An essay by Sonia Cavicchiolo explores the way that the depiction of Mary Magdalene changed in the Baroque period, starting with Carava io’s penitent (c.1596–97; Galleria Doria Pamphilj) and Rubens’s weeping gure at the foot of the Cross (1617–19; Musée du Louvre). These gures re ect the saint’s post-Tridentine paradigmatic role as an embodiment of penance in the light of the Church of Rome’s stance on the sacraments, which had been challenged by the Protestants. In Guido Cagnacci’s Conversion of Mary Magdalene (1661; Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena), the semi-nude saint is chastised by her sister Martha, whereas paintings by Georges de la Tour – for example that of c.1640 in the National Gallery of Art, Washington – and Domenico Fetti (c.1617; Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome) show her meditating with a skull and book. The exhibition included works by Cagnacci (no.7.28; Fig.7), Alessandro Rosi (c.1670; Gallerie degli U zi; no.7.29) and Simon Vouet (1649; Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon; no.7.30) showing the bare-breasted saint in a state of spiritual ravishment, or ecstasy, which according to Ignatius of Loyola, was the ultimate aim of meditation, the reunion of the soul with God. Francesco Furini’s penitent Magdalene (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), painted c.1633, the year that the artist was ordained, shows the saint naked, except for a strategically placed strand of hair. Cavicchiolo describes her as a ‘sinuous nude’ whose ‘eroticism is revealing and disturbing’ (p.131).

5. Supper in the house of the pharisee, by Moretto da Brescia. 1550–54. Oil on canvas, 207 by 140 cm. (S. Maria in Calchera, Brescia; Bridgeman Images).

6 M. Hirst: Tre Saggi su Michelangelo, Florence 2004, p.22; and W.E. Wallace: ‘Il “Noli me Tangere” di Michelangelo: tra sacro e profano’, Arte Cristiana 76 (1988), pp.443–50, at p.448. 7 See S. Haskins: ‘Foreword’, in M.A.

The many faces of Mary Magdalene

6. Penitent Mary Magdalene, by Antonio Canova. 1808–09. Marble, height 95 cm. (State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg). 7. Penitent Mary Magdalene, by Guido Cagnacci. 1625–27. Oil on canvas, 86 by 72 cm. (Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome; Bridgeman Images).

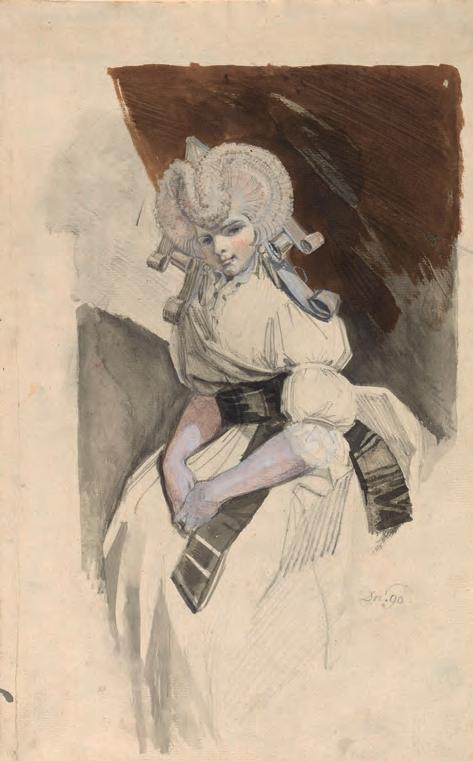

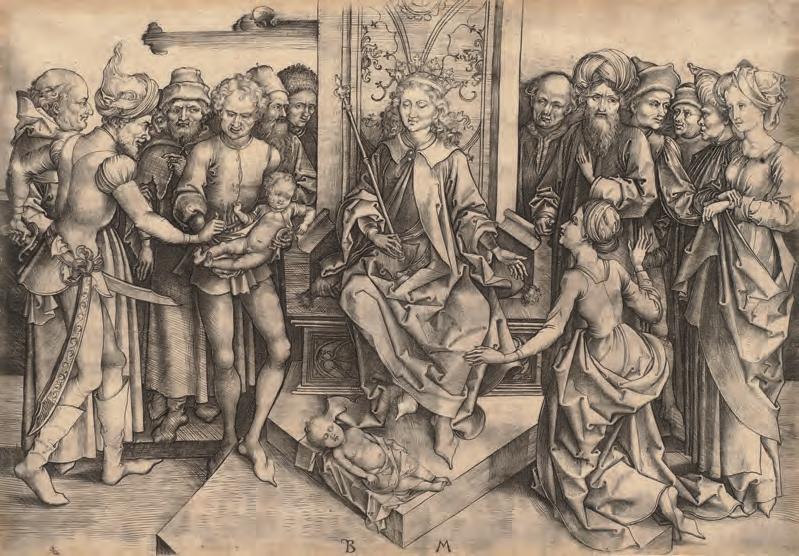

A thoughtful, comprehensive essay by Mazzocca, ‘Tra Neoclassicismo e Simbolismo’, traces Mary Magdalene’s iconographic fortunes from Correggio’s St Mary Magdalene reading (after 1517; private collection) to the naked Magdalenes of the late nineteenth century, encompassing such artists as Sebastiano Conca, Benedetto Luti and Anton Raphael Mengs (who converted to Catholicism at the time he painted his first penitent Magdalene, c.1752). A lost painting by Pompeo Batoni after Correggio of the Magdalene reading was represented in the exhibition by a copy by Józef Wall (1779–82; Castello Reale, Warsaw; no.8.7). The depictions of the naked Magdalene, which were often kept as devotional images in the bedrooms or studioli of royal and aristocratic collectors, were clearly intended for the male gaze. Antonio Canova’s kneeling Penitent Magdalene (no.8.9, not exhibited; Fig.6) and Reclining Magdalene (no.8.10) took the image of the saint to a new level, ‘free of any devotional purpose’ (p.140), to become, we are told, a universal symbol of tormented femininity. As copied in paint by Fernando Cavalleri (1816; Castello Ducale, Agliè; no.8.15) and again by Natale Schiavoni for the Emperor Franz I of Austria (c.1830; Belvedere, Vienna), several variants of which were included in the exhibition, Canova’s Magdalene sheds not only her clothes but also her already tenuous relationship with her biblical self and even with the legendary naked hermit and penitent in the desert. She becomes instead a kind of ‘modern reincarnation of the motif of melancholy’ (p.143) trapped between a rock and a hard place. For Mazzocca, Francesco Hayez, a ‘libertine’ celebrated for the sensuality of his nudes, depicted the ‘entirely profane’ Magdalene as a ‘true Romantic heroine’, ‘bursting with sensuality’ (p.143).

Mazzocca’s essay is accompanied in the catalogue by a phalanx of penitent Magdalenes in paesaggio, which include the ‘disconcerting realism’ (p. 144) of Domenico Induno’s well-endowed anchorite (c.1848–50; private collection; 9.14). There are also Magdalenes in paintings by Victor Orsel (1825; Musée de Poitiers; no.9.2) – in which, according to Stefano Bosi, the saint’s ‘bare breast’ apparently symbolises ‘her eremitical life’ (p.495) – Enrico Scuri (1864; Museo Civico Ala Ponzone, Cremona; no.9.15), which depicts her with a brightly lit bare haunch, and Paul Baudry (1858; Musée d’Arts de Nantes; no.9.18). This sequence culminates in Jean-Jacques Henner’s lubricious nymph (1860; Musée d’Unterlinden, Colmar; no.9.19) and writhing nudes by Jules Joseph Lefèbvre (c.1876; State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg; no.9.22) and Marius Vasselon (1887; Musée des Beaux Arts, Tours; no.9.23). In such paintings, the depiction of the ‘apostola apostolorum’ has become entirely divorced from any religious function. In the catalogue, this is given a twenty-first-century gloss by Brunelli in his introduction and by Mazzocca in his essay. Mazzocca presents these works as a symbol of modern and provocative femininity which ‘did not fear to show itself in all its erotic character’ (p.144), despite the fact that meditation and melancholy were Romantic motifs, the reason why the subject was adopted by sculptors in this period, such as Pompeo Marchesi in his Penitent Magdalene (1832; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). Despite the curators’ attempt to justify such paintings as evidence of female sexual liberation, it is hard to avoid seeing them as anything other than pious pornography.

Erhardt and A.M. Morris: Mary Magdalene: Iconographical Studies from the Middle Ages to the Baroque, Leiden and Boston 2012, at p.xxxi; and idem: Mary Magdalen: The Essential History, London 2005, p.147.