6 minute read

Against the Avant-Garde: Pier Paolo Pasolini, Contemporary Art, and Neocapitalism, A.H. Merjian by robert silberman

child (Fig.15), as the servant shown in a portrait of Landgravine Philippine (Fig.14). The servant, dressed in Hesse-Kassel livery, hands Frederick II’s second, then childless, wife a basket of flowers as reference to her blossoming youth. The landgravine holds a bouquet to her heart and looks at the viewer. Her refinement and ostensible wealth seem to compete with the beauty of the delicate boy. It is possible that he was Selim Schwartz, who is documented at the Kassel court in 1774 and 1780. He was brought to Kassel by force and became the landgravine’s servant after completing a Protestant religious education and receiving baptism. Some servants who had been brought to the west by the slave trade made careers at European courts, but others became homeless and unhappy. Selim Schwartz took his life in Fulda on 19th March 1780.

This stimulating exhibition tells many fascinating stories of the creation of Tischbein’s paintings. The present reviewer would have wished for a less crowded hang for the cleverly installed exhibition. The room has the advantage, however, of being located centrally in the magnificent Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister. Thus, after visiting the exhibition, visitors can admire the Dutch and Italian masterpieces that Landgrave Wilhelm VIII acquired for Kassel and that provided inspiration for artists such as Tischbein.

Advertisement

1 The exhibition Guido Reni: The Divine (23rd November 2022–5th March 2023) will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue. For the Bernardo Bellotto exhibition, see M. Haas, ed.: exh. cat. Remember Venice: Bernardo Bellotto zeichnet, Darmstadt (Hessisches Landesmuseum) 2022–23. 2 See M. Miller et al.: exh. cat. Tischbein: Meisterwerke des Hofmalers, Eichenzell (Museum Schloss Fasanerie) 2022, to which this reviewer contributed two entries. 3 Accompanying booklet: Der Maler als Zeichner – der Zeichner als Maler: 300 Jahre Johann Heinrich Tischbein d. Ä. Edited by N. Callebaut et al. 143 pp. incl. numerous col. ills. (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, 2022), €7.50. ISBN 978–3–931787–69–1. 4 See, for example, M. Eissenhauer: exh. cat. 3 x Tischbein und die europäische Malerei um 1800, Leipzig (Museum der Bildenden Künste) and Kassel (Neue Galerie) 2005–06; and P. Tiegel-Hertfelder: ‘Historie war sein Fach’: Mythologie und Geschichte im Werk Johann Heinrich Tischbeins d. Ä. (1722–1789), Worms 1996. See also https://datenbank.museumkassel.de/0/T57180/0/0/2/1/0/objektliste. html?katalogauswahl=Sammlung, accessed 15th December 2022.

Courtauld Gallery, London 14th October 2022–8th January 2023

by kevin salatino

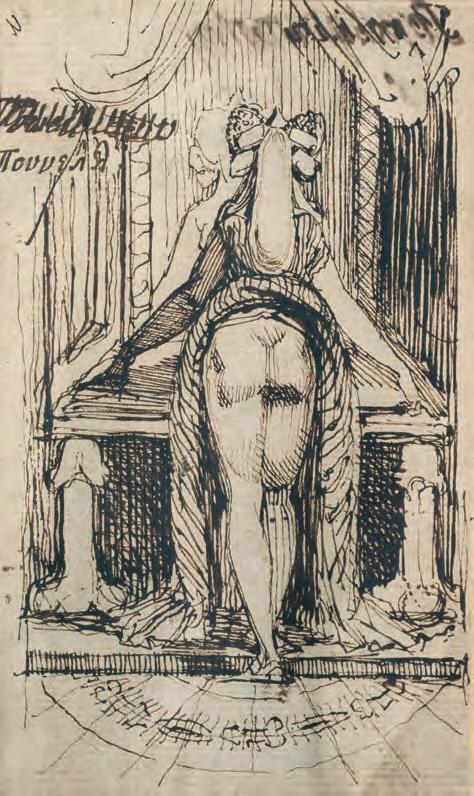

Of Henry Fuseli’s many ‘shockingly indelicate’ drawings, as John Flaxman described them, none is more shocking or more indelicate than his study of a dominatrix using an elaborate strap-on dildo on a figure bent over a chair (Museo Horne, Florence).1 And although that sketch, which he made in Rome in the 1770s, is not included in this riveting exhibition of Fuseli’s drawings of the ‘modern woman’ (organised with the Kunsthaus Zürich), there are enough kindred works to give the visitor a bracing sense of what the eccentric and visionary painter of The Nightmare (1781; Detroit Institute of Arts) was attempting in his moments of greatest graphic liberty and libertinage.2

The famously splenetic Benjamin Haydon memorably described Fuseli’s female protagonists as ‘whores [. . .] with the look of demons [who] have the actions of galvanized frogs’, whereas Fuseli himself, Haydon claimed, ‘was engendered by some hellish monster on the dead body of a speckled hag’.3 So hyperbolic is Haydon’s language that, one speculates, he must have seen at least some of the artist’s controversial drawings, most of which, as Fuseli’s biographer Alan Cunningham assures us, were burnt after his death. ‘Nor do I blame the hand of the widow who kindled it’, Cunningham primly added.4

That widow was Sophia Rawlins, an artist’s model whom Henry married in 1788 when he was forty-seven and she was twenty-five or twenty-six. Of the fifty drawings on view (plus one by John Brown; c.1775–80; cat. no.36), more than half depict the artist’s wife, either literally or allegorically, making the exhibition, in large part, a visual biography of Sophia, the obsessive subject/object of her husband’s affection.5 In most of them she is highly fetishised, sporting extravagant, indeed bizarre, hair or headdresses, and elaborately costumed in either the latest fashion or in historically inspired inventions. And while her breasts are often exposed, her face whitened and her cheeks heavily rouged à la cortigiana, of all her strange accoutrements, her coiffures take the proverbial cake.

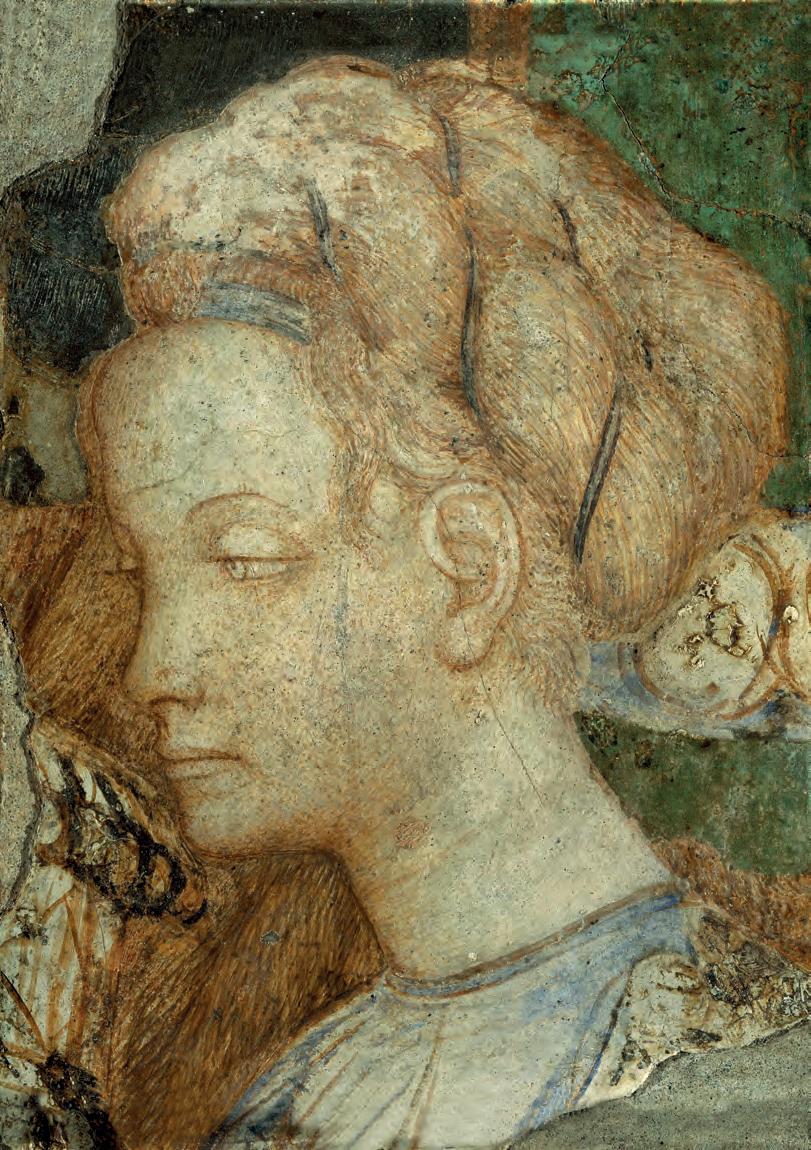

A number of historical sources may be adduced as inspiration for the Fuselian head, including Michelangelo’s teste divine drawings and ancient Roman (Flavian) portrait busts, the putative influences behind, in the first case, an outlandish headdress resembling a pair of ram’s horns (no.7; Fig.16) and, in the second, a hairdo of upswept rows of tight curls that calls to mind the ‘Teddy Boy’ style of the 1950s (1799; Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg; no.6). If, as David Solkin, the curator of this exhibition, speculates in the superb accompanying catalogue, Sophia herself designed and created some of these remarkable concoctions, ‘she deserves to be credited with as much

16. Sophia Fuseli, her hair in large rolls, with pink gloves, in front of a brown curtain, by Henry Fuseli. 1790. Graphite, brush and watercolour, heightened with white opaque watercolour on paper, 31.6 by 19.7 cm. (Kunsthaus Zürich; exh. Courtauld Gallery, London).

artistry as her husband’ (p.30). In this reviewer’s opinion the designing and creating were a family affair, but this does not diminish Sophia’s alleged achievement.

Handsomely installed in the Courtauld’s new Denise Coates Exhibition Galleries, with loans from fifteen public institutions and seven private collections, Fuseli and the Modern Woman is a rare opportunity to see a body of work that constitutes, as Solkin revisionistically declares, ‘one of the thematic [. . .] cornerstones of [Fuseli’s] career’ (p.34), ushering in ‘a period of stylistic and technical experimentation without precedent in his practice’ (p.44). Surprisingly, no show devoted to this compelling and provocative material (constituting more than one tenth of approximately 1,300 extant drawings by the artist) has ever been mounted. Divided into three thematic groupings, the exhibition unfolds as both a narrative and a défilé de mode.

The section ‘The Medusa of the Hearth’ focuses, as the wall text indicates, ‘on Fuseli’s fetishistic preoccupation with female hairstyles of extraordinary complexity, [. . .] mainly of his wife’, observing that such ‘displays of artifice were commonly associated with [. . .] courtesans’. It could be argued, of course, that this is the focus of the entire exhibition, but it helps to break up what might otherwise seem a relentless progression of increasingly eccentric femmes fatales into semiotic or iconographic taxonomies. In Fuseli’s profoundly private and performative portrayals of his wife, for example, Sophia can be said to adopt a number of potentially identifiable characters (such as coquette, courtesan, dominatrix or simply fashion plate), presumably known and understood by the Fuselis but now largely irretrievable. She can also be seen to exercise a good deal of personal autonomy. ‘The Other Side of Venus’ explores Fuseli’s images of women (again, mostly Sophia) rendered from behind, a particular fetish of his. A dozen drawings fall into this category, several of which are large, highly finished works in watercolour and gouache (no.27; Fig.17). Sophia’s