6 minute read

Modigliani Up Close by bart j.c. devolder

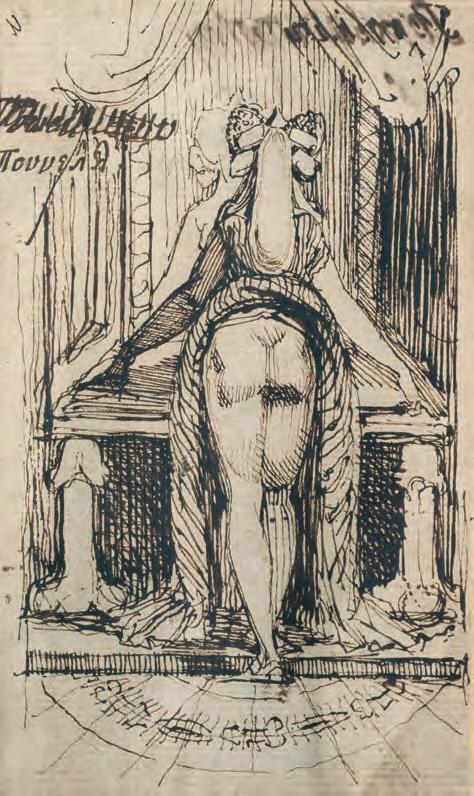

2. View of the Logge in the Vatican, by Ludwig Gruner. 1844. Chromolithograph, 54.8 by 37.3 cm. (page). (From Fresco Decorations and Stuccoes of Churches and Palaces in Italy during the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, with Descriptions by Lewis Gruner, London 1844; Royal Collection Trust; © HM King Charles III 2023).

catalogue was able to demonstrate their educational importance for local culture. Raphael painted his earliest known altarpieces for an Umbrian town of a similar scale to Stendal, Città di Castello. The town revisited old glories by restaging the exhibition on the young Raphael seen there in 1983, albeit with more loans of works by him.7 It succeeded in presenting several fresh aspects of the young artist, including a judicious digital reconstruction of his St Nicholas of Tolentino altarpiece (1501), of which only fragments survive in various collections, following the damage it incurred during an earthquake in 1789.

Advertisement

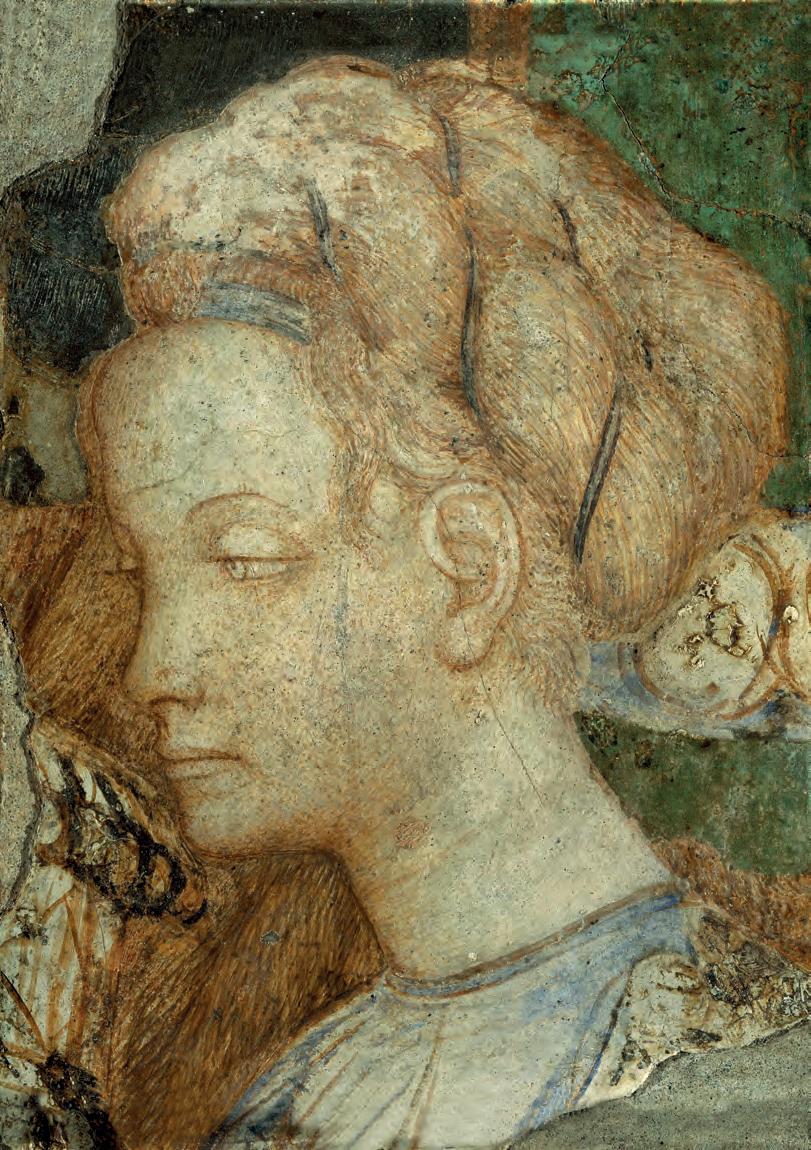

Among the four paintings by Raphael for Città di Castello the only one that has remained in the town until the present day is a doublesided canvas banner (gonfalone), which underwent fresh conservation for the exhibition (Fig.1). The disconcerting results reveal not only that restoration carries technical risks but also that the removal of later overpaint can have an irreversible impact on a work. In 1952 the banner underwent restoration intended to remove all the additions made since Raphael’s time. The exhibition’s catalogue contains two considered essays on the challenge presented by the resulting lacunae in the banner’s paint surface. The task of improving the visually unhappy effects of the removal of the overpaint had prompted an earlier conservation campaign, in 2006, when the late Anna Maria Marcon, an experienced restorer who worked at the Istituto Centrale di Restauro, Rome, stated the danger of ‘forging a state of preservation’, creating confusion about which areas were damaged and making the underdrawing illegible by partial infills.8 Modern digital technology would have made it possible to create an image of what the banner might have looked like without interventions on the original.

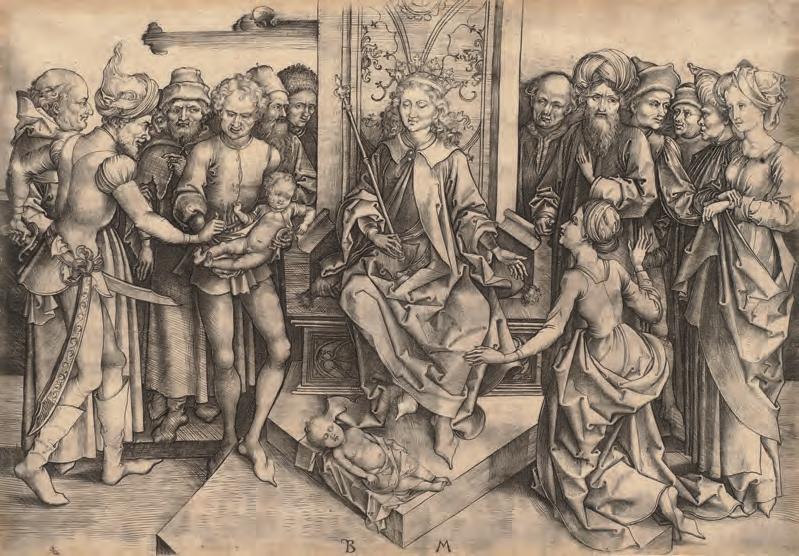

Berlin offered a pair of exhibitions, each of which impressively revealed Raphael’s genius in a nutshell, one of drawings by him in the collection of the Kupferstichkabinett, the other a display at the Gemäldegalerie of its five early Madonnas, which were accompanied by the first-ever international loan from the National Gallery, London, of the Madonna of the pinks (1507).9 The Kunsthalle in Hamburg unveiled an unexpected tradition of local collectors, who in this Protestant environment assembled prints by and after this overtly papal artist as well as early photographs of his works.10 The exhibition also included a colour lithograph by Ludwig Gruner, published in 1844, which documents the lost original majolica floor made by Luca della Robbia the Younger to Raphael’s design for the Vatican Logge (Fig.2), and culminated in a display of the museum’s own five supposed autograph drawings.

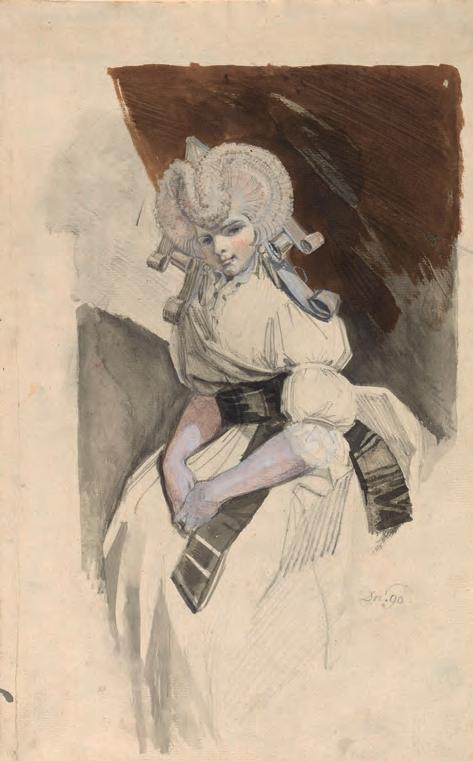

Dresden exhibited its set of the tapestries woven at the manufactory at Mortlake from Raphael’s cartoons for the Sistine Chapel following their acquisition in 1623 by the future Charles I (Fig.3). This focused exhibition addressed the topic to which the celebrations in several instances will probably make one of their lasting contributions to scholarship.11 Casts from ancient Roman sculptures tried to evoke, slightly theatrically, the stylistic environment in which Raphael created his designs. A remarkable drawing in a private collection of studies including cranes and other birds for one of the cartoons by Giovanni da Udine, one of Raphael’s most important collaborators, known for decades only through photographs, was on show.12

The Victoria and Albert Museum provided scholars with an extraordinary scholarly tool by making a high-resolution recording in colour, 3D and infra-red of the tapestry cartoons – the greatest cycle of High Renaissance paintings outside Italy – available on the internet.13 The refurbishment of the Raphael Gallery sadly lacked the funds to improve the visibility of the cartoons by replacing the coloured protective glass.

6 C. Whistler and B. Thomas, eds: Raphael: The Drawings, Oxford (Ashmolean Museum) 2017; and A. Gnann, ed.: exh. cat. Raphael, Vienna (Albertina) 2017–18, both exhibitions were reviewed by Tom Henry in this magazine, 160 (2018), pp.226–33. 7 A.M. Mercalli and L. Teza: exh. cat. Raffaello Giovane a Città di Castello e il suo sguardo, Città di Castello (Pinacoteca Comunale) 2021. 8 A.M Marcone: ‘Lo Stendardo della Trinità: tecniche di esecuzione e intervento di restauro’, in T. Henry and F.F. Mancini, eds: exh. cat. Gli esordi di Raffaello tra Urbino, Città di Castello e Perugia, Città di Castello (Pinacoteca Comunale) 2006, p.154. 9 Accompanying publication: D. Korbacher: Raphael in Berlin: Masterpieces from the Kupferstichkabinett and The Madonnas of the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin 2020. 10 A. Stolzenburg and D. Klemm: exh. cat. Raffael – Wirkung eines Genies, Hamburg (Hamburger Kunsthalle) 2021. A British parallel was an exhibition at the Lightbox, Woking, on the collection of reproductions of Raphael’s works formed by Prince Albert, Raphael: Prince Albert’s Passion (3rd October 2020–31st January 2021), reviewed by Michael Hall in this Magazine, 163 (2021), pp.64–67. 11 S. Koja: exh. cat. Raffael – Macht der Bilder: Die Tapisserien und ihre Wirkung, Dresden (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister) 6th June–30th August 2020. See also S. Koja: exh. cat. Raphael – The Power of Renaissance Imagery: The Dresden Tapestries and their Impact, Columbus OH (Museum of Art) 2022. The present author contributed an essay to the catalogue. For further recent contributions to the study of Raphael’s tapestries, see A.C. Baiardi and N.F. Grazzini: exh. cat. Sul filo di Raffaello: Impresa e fortuna nell’arte dell’arazzo, Urbino (Galleria Nazionale delle Marche) 2021; and A. Enzensberger, ed.: Apostel in Preussen, Berlin 2020. 12 See L. Mohr, entry in Koja 2022, op. cit. (note 11), pp.54–57, figs.1 and 2. 13 See www.vam.ac.uk/articles/explorethe-raphael-cartoons, accessed 19th December 2022.

3. St Paul preaching in Athens, by the Mortlake Tapestry Manufactory after a cartoon by Raphael. After 1625. Wool, silk and linen tapestry, 433 by 538 cm. (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden).

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, put on its own megashow, Raphael’s Line 1520–2020 (10th December 2020–28th March 2021), which drew on museums and private collections in Russia to display both works by Raphael and his legacy up to the present time, augmented by loans of drawings from major European collections. An unobtrusive installation inside the ostentatious state rooms of the tsars assembled the newly restored frescos by Raphael’s workshop or followers that once decorated the loggia of the Villa Stati-Mattei on Rome’s Palatine Hill. For anyone who could not get to St Petersburg or obtain the accompanying publication Liniia Rafaelia: 1520–2020 (ArtVolkhonka publishing house, Moscow), the inclusion of the room on the Hermitage’s online video tour is a valuable compensation.14 Although a powerful demonstration of the medium, this makes it evident that there is no substitute for first-hand examination of these enigmatic frescos. The Hermitage’s marble Dead boy on a dolphin (Fig.5) was not shown in the exhibition, and whatever one thinks of the attribution to Raphael its inclusion could have stimulated new discussion about this enchanting sculpture.15

The anniversary celebrations hinged on the two blockbuster exhibitions in Rome and London, like a pair of batwing doors, unnecessarily competing with each other. Both took a monographic approach and both aimed to present all the artist’s activities. Major efforts were made to market the artist: the Rome exhibition was claimed to be ‘the largest ever devoted to Raphael and one of the most important staged in Italy’ and that in London was advertised as presenting ‘the entire range of Raphael’s artistic production. No exhibition in the UK has ever done this’. One can certainly agree with John Booth, chairman of the National Gallery’s Trustees, who stated in a film promoting the show that ‘this is an important event for the National Gallery, for the artist, and for our understanding of him’, although a dead artist can

14 The virtual tour is available at www.pano.hermitagemuseum. org/3d/html/pwoaen/raphaelmain/, accessed 14th December 2022. 15 A. Nesselrath: Das Fossombroner Skizzenbuch, London 1993, p.31. 16 As stated in the introductory panel to the exhibition and the opening text in the booklet accompanying the exhibition. 17 A. Blunt: ‘Art under Capitalism and Socialism’, in C. DayLewis, ed.: The Mind in Chains, London 1937, pp.103–22, at p.111.