4 minute read

Angus Trumble (1964–2022 by andrew hopkins

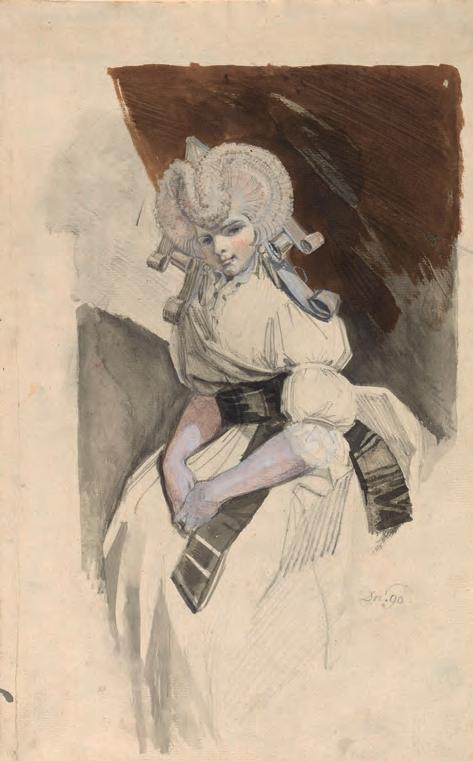

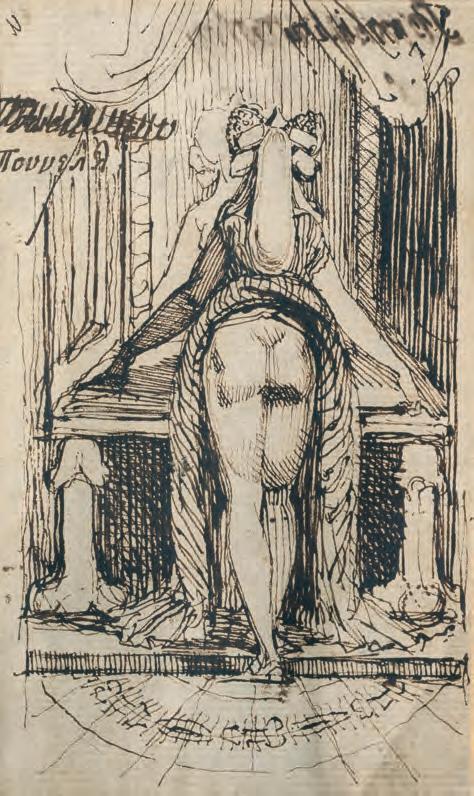

majestic swaying figure – an exercise in clothed contrapposto – is rooted to the ground like an oak tree, while her coiffure, seen from the rear, assumes ever more fantastic and suggestively phallic forms. One of this group, the small but powerful Kallipyga (no.24; Fig.18), is among the most objectifying and erotic in the exhibition, its implicit threat of sexual violation implicating both artist and viewer. It depicts Sophia leaning against an altar-like console with ithyphallic supports, staring into a mirror, her skirts hiked up above her waist to expose her buttocks. The floor’s pattern of alternating disembodied male and female genitalia makes plain the drawing’s message. ‘Dangerous Liaisons’, the final section, addresses Fuseli’s unambiguous renderings of courtesans. Again, Sophia clearly posed for some of these, whereas others depict actual (or imagined) sex workers. Still others, the most outré, come from the realm of purest fancy, their startlingly creative and ever-more architectonic head gear defying both gravity and belief. Some of the works in this group, such as The Debutante (1807; Tate; no.41) and Allegory of Vanity (1811; Auckland Art GalleryToi o Tāmaki; no.65), are among the most beautiful in the exhibition, as accomplished as any of Fuseli’s better-known drawings.

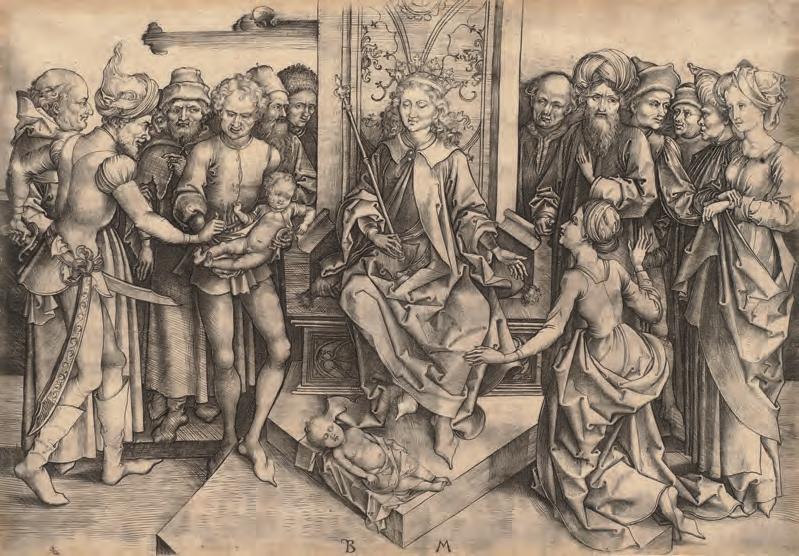

A disturbing subcategory in this section depicts women enacting enigmatic rituals of sadistic violence. In them, the artist’s dominatrices (a lifelong obsession) achieve the inevitable Fuselian apotheosis into madwomen and murderesses, blithely indulging in sexual torture, mutilation, dismemberment and infanticide. Most of these are private penseés, unsettling products of Fuseli’s darkest fantasies. Unlike anything else of the time, they are also a testament to his unfettered mind and Gothic sensibility. All of them (indeed, most of the drawings on view), it should be emphasised, were clandestine, shown by Fuseli only to a select few, far too ‘indecent’ ever to have been made public. That they survive at all is miraculous.

Advertisement

Showcasing Fuseli’s graphic invention and abiding strangeness, this deeply intelligent exhibition and its catalogue are a substantial contribution to Fuseli studies. More significantly, they also enlarge our understanding of proto-Romantic art and thought, expand our perception of the erotic and pornographic in the long eighteenth century and further problematise the depiction, reception and agency of women – modern or not – in a patriarchal age that confined them, in the memorable words of the Fuseli-besotted Mary Wollstonecraft, ‘in cages like the feathered race’, with ‘nothing to do but to plume themselves and stalk with mock majesty from perch to perch’.6

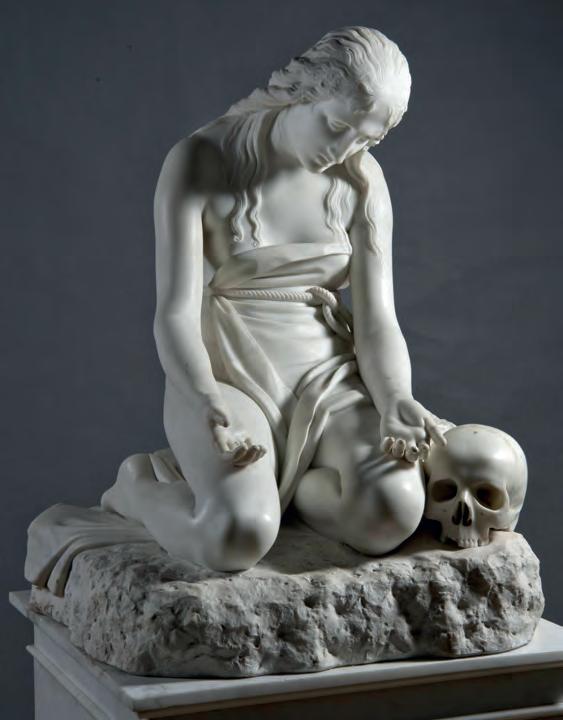

Opposite 17. Woman in a sculpture gallery, by Henry Fuseli. 1798. Pen and black ink, brush and watercolour on paper, over graphite, heightened with white opaque watercolour, 41 by 24.7 cm. (Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden; exh. Courtauld Gallery, London). 18. Kallipyga, by Henry Fuseli. c.1790–92? Pen and brown ink, 16.3 by 9.4 cm. (Private collection; exh. Courtauld Gallery, London).

1 John Flaxman’s description concerned a group of ostensibly obscene drawings discovered shortly after Fuseli’s death, as recorded by Benjamin Robert Haydon. See T. Taylor, ed.: Life of Benjamin Robert Haydon, Historical Painter, from his Autobiography and Journals, London 1853, II, p.129. 2 Catalogue: Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism. Edited by David H. Solkin and Ketty Gottardo, with contributions by Jonas Beyer, Mechtild Fend and Ketty Gottardo. 168 pp. incl. 75 col. ills. (Paul Holberton, London, 2022), £30. ISBN 978–1–913645–29–8. 3 Diary entry for December 1815 in W.B. Hope, ed.: The Diary of Benjamin Robert Haydon, Cambridge MA 1960–63, I, pp.488–89. 4 Cunningham was wrong. Although some of Fuseli’s erotic drawings may have been burned, many clearly were not. A. Cunningham: The Lives of the Most Eminent British Painters, London 1879, I, p.100. 5 The catalogue’s checklist contains sixtyfive drawings, fifty-one of which are on view in London whereas fifty-nine will appear in the exhibition’s second iteration, at the Kunsthaus Zürich (24th February–21st May 2023). Six of the drawings appear only in London, fourteen only in Zürich. 6 S. Tomaselli, ed.: Wollstonecraft: A Vindi-cation of the Rights of Men and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Cambridge 2012, p.130.

Modigliani Up Close

Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia 16th October 2022– 29th January 2023

by bart j.c. devolder

The Barnes Foundation has selected an ambitious concept for the exhibition that accompanies its centennial celebration, one in which several years of collaborative and interdisciplinary research on the working methods and materials of Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) take centre stage.1 It is a unique opportunity to showcase this form of scholarly research, which is still too often buried in the footnotes of catalogues and articles. By making such technical information the raison d’être for this exhibition, the Barnes Foundation deserves praise, as it does also for its success in securing the loans of the fifty works on display. The exhibition is divided into five chronological sections, the first two of which have several sub-sections – an organisational approach that reflects the significant technical shifts in the evolution of the artist’s working process. Each gallery is dazzling and one can only imagine how much more spectacular they would look if the twelve Modigliani paintings in the collection were hung among them, but according to the terms of Albert C. Barnes’s will they cannot be moved.

After a short introductory text, visitors encounter a germane selfportrait of the artist holding a painter’s palette (cat. no.59; Fig.20) and in section 1B they are drawn further into