Picasso’s ‘Faun musician’: revealing the making, contextualising the meaning

Technical examination of a drawing in the Art Institute of Chicago made by Picasso in June 1947 of a faun playing a double ute revealed not only that it had been taken from a copy of Louis Aragon’s translation of sonnets by Petrarch but also that it overlay and transformed earlier drawings by Picasso of a vase of owers.

by KRISTI DAHM, FRANCESCA CASADIO and JEAN-LOUIS ANDRAL

CALLIGRAPHIC LINES SPIRAL and intertwine to form the head and arms of a faun playing a double Greek ute amid leafy branches in a gouache and ink drawing made by Pablo Picasso in 1947, The faun musician (Fig.3).

Images of the goat-man hybrid proliferate throughout Picasso’s œuvre in works of all media and the faun may be understood, through his characterisation as a jovial seducer, as a mythological alter ego for the artist.1 Picasso painted this small gouache, which he dated 7th–11th June 1947, within the month following the birth of his son Claude to Françoise Gilot (b.1921) on 15th May.

When scrutinised closely, colours and forms unrelated to The faun musician can be observed just below the surface of the drawing, su esting design changes or another composition beneath. Bright orange, pink and green are readily visible through ink losses in the horns and nose (Figs.1 and 2), while along the centre of the image vestiges of earlier lines and forms are visible under the blue-grey background. These observations prompted the present authors to unframe the work for study, which led to a series of unexpected discoveries.

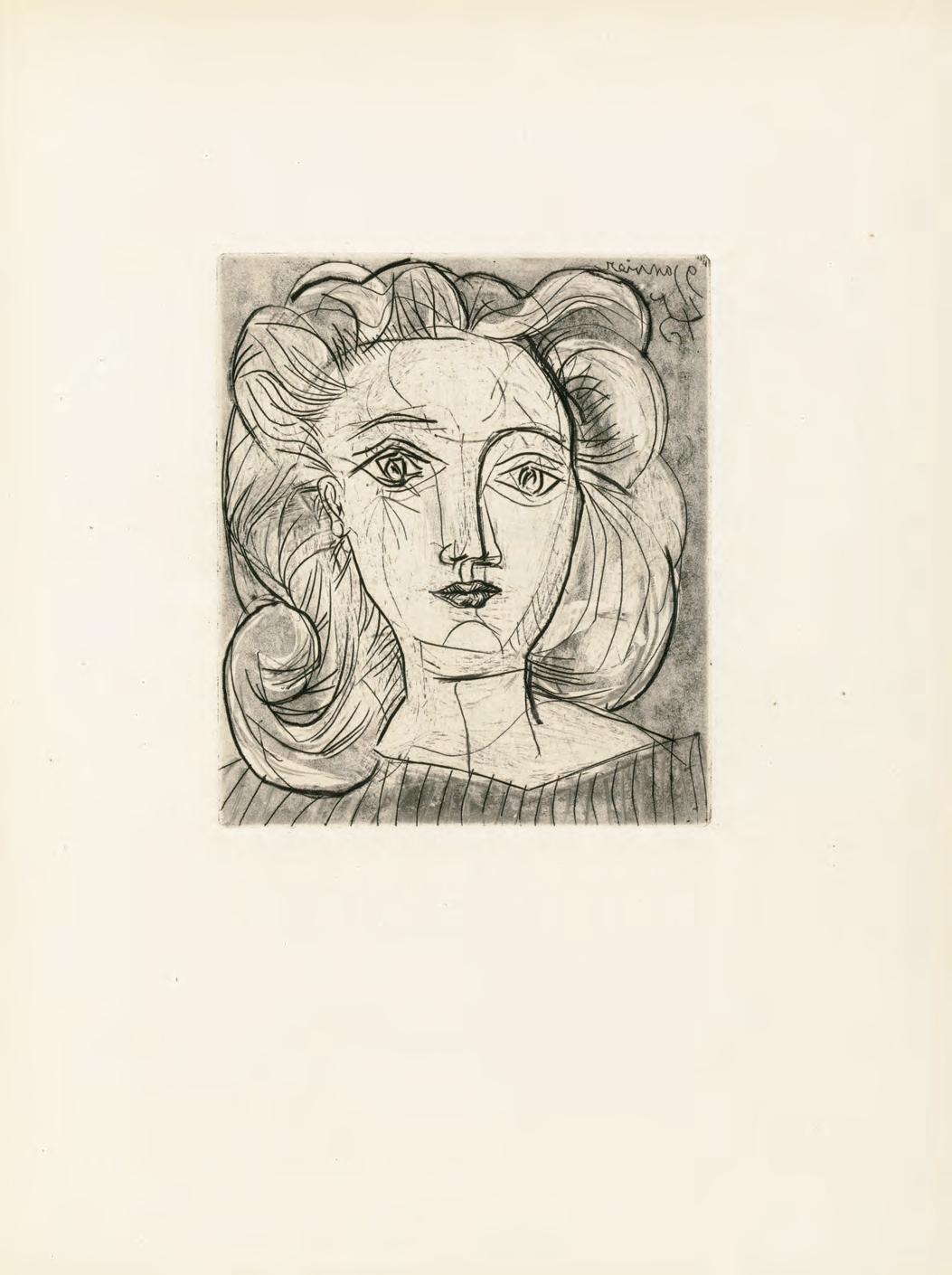

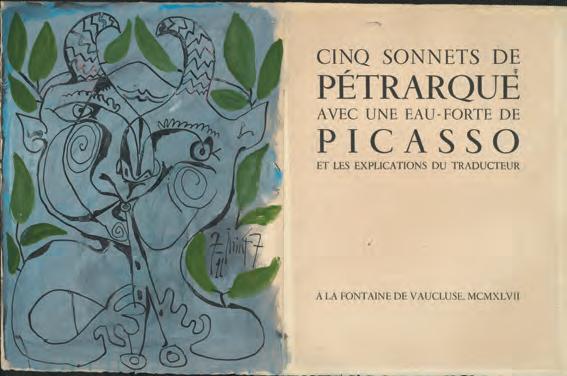

The paper support, the edges of which had been long concealed by the mount and frame, was revealed to be a folded folio that incorporated the title page from a copy of a limited edition artists’ book published in 1947, Cinq sonnets de Pétrarque / avec une eau-forte de / Picasso / et les explications du traducteur (Fig.6), translated by the poet Louis Aragon, to which Picasso contributed an intaglio illustration, Head of a woman (Fig.4), appearing on the sixth unnumbered leaf in the volume (recto).2 Sewing holes along the centrefold con rm that the Chicago folio was once part of a bound book printed on wove paper watermarked ‘ARCHES’. Picasso painted The

The authors wish to thank Alonso Rickards for early research contributions to this article and Vérane Tasseau for providing additional illuminating evidence about the 6th June Head. Emily Ziemba researched the provenance of the Chicago drawing. The authors are grateful to Emeline Pouyet and Marc Walton for their work on the hyperspectral imaging and contributions to the creation of macroXRF images. The Conservation and

Science department at the Art Institute of Chicago benefits from the generous support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Grainger Foundation.

1 P. Picasso and J. Richardson: Pablo Picasso: Aquarelle und Gouachen, Basel 1956, n.p., no.31.

2 The book contains twenty-four unnumbered leaves from six sheets.

S. Goeppert et al.: Pablo Picasso The Illustrated Books: Catalogue Raisonné, Geneva 1983, p.130.

1. Detail of Fig.3.

2. Photomicrograph of The faun musician (bottom), showing orange and pink media from an earlier composition visible through losses in the uppermost black ink layer.

Opposite

3. The faun musician, by Pablo Picasso. 7th–11th June 1947. Brush and black ink and gouache on cream wove paper, folded, 32.7 by 50.2 cm. (Art Institute of Chicago; © 2020 Estate of Pablo Picasso; DACS, London, 2022).

faun musician on the blank frontispiece opposite the title page as a means of personalising or dedicating a copy of the book. The folio must have been removed from the book at some point before its first presentation as an independent drawing, in the exhibition Picasso. Dessins – Gouaches – Aquarelles. 1898–1957 (6th July–2nd September 1957) held at the Musée Réattu, Arles, to which it was lent by the Saidenberg Gallery, New York.3

Visible traces on the drawing surface – clues to the changes that the drawing underwent before becoming The faun musician – and its intriguing origin in a book prompted an in-depth study to probe the layers beneath. Images generated by non-invasive scientific analyses led to the discovery that Picasso initially drew two different versions of a still life with a vase of flowers beneath the faun.4 The sequence of production and the transformation of the two versions of the still life into the faun musician can now be more fully understood and placed in a broader art-historical context. In addition, it becomes possible to re-examine The faun musician and the underlying still lifes in relation to the literary themes of Petrarch’s sonnets and consider new associations between visual and literary imagery. Knowing the book’s format, one can also explore how each image would

Opposite

4. Head of a woman – Françoise, by Pablo Picasso. 1945. Etching, aquatint and engraving on Arches wove paper, plate 13.9 by 11.9 cm., sheet (irreg.) 32 by 24.8 cm. (From Cinq Sonnets de Pétrarque, plate, fol.6.; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Scala; © 2020 Estate of Pablo Picasso; DACS, London, 2022).

5. Vase with foliage and three sea urchins, by Pablo Picasso. 21st October 1946. Oleoresinous enamel paint and charcoal on paper mounted on reused canvas, 46 by 38 cm. (Musée Picasso, Antibes; © imageArt; photograph Claude Germain; © Succession Picasso 2022; DACS, London, 2022).

Above right

6. The faun musician, by Pablo Picasso, open folio as it originally appeared as a frontispiece opposite the title page to Cinq Sonnets de Pétrarque. (© 2020 Estate of Pablo Picasso; DACS, London, 2022).

Picasso’s ‘Faun musician’

have been encountered by the reader and how they would have functioned in sequence with the book’s other contents. Through this process, whereby materials make meaning, we can posit that Picasso’s engagement with the contents of the volume embraced the spirit of playful reinvention that reverberated during the immediate après-guerre. Mirroring Aragon’s innovative approach to the lyrical translation, Picasso also adopted a novel, creative dialogue with tradition.5

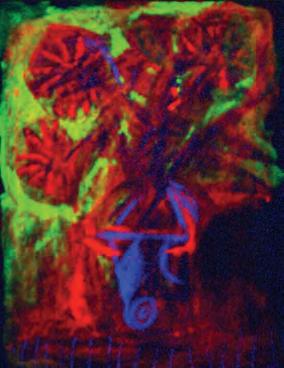

Picasso’s practice of painting one image over another has been well documented in his oil paintings but rarely for his works on paper.6 Infra-red reflectography (IRR) images of The faun musician reveal Picasso previously drew a still life with a vase of flowers on the page where the faun now appears (Figs.10 and 11). Digital processing of the IRR image clearly revealed an oval-shaped vase centred in the lower half of the sheet, with five to seven flower heads angled in various directions above it. A dark horizontal line in ink demarcates the upper third of the vase and could represent water seen through transparent glass or a decorative feature on a ceramic surface. Several large leaves complete the bouquet. Bright pink, orange and green pigments visible through surface losses under natural light correspond to the location of flowers and leaves respectively and indicate a bold palette. The spiral shape on the bottom half of the vase could represent a perspective rendering of its base, a device Picasso used in the paintings of vases of flowers that he is known to have made in Vallauris in 1947 and 1948 (Fig.7).

Compositional elements can be interpreted through comparison with other works of the period. In his oil painting Flowerpot, dated 3rd January

3 Picasso and Richardson, op. cit. (note 1), n.p., no.31; and D. Cooper: exh. cat. Picasso. Dessins – Gouaches –Aquarelles. 1898–1957, Arles (Musée Réattu) 1957, n.p., no.69. The provenance is as follows: Saidenberg Gallery, by 1956 to at least 1964, exhibited in 1957 at Musée Réattu, Arles, see Picasso and Richardson, op. cit. (note 1); Sale, Parke-Bernet Gallery, New York, ‘19th and 20th-century Drawings and Watercolors’, 17th December 1969, lot 85, when the provenance was given as ‘Property of a Midwestern Museum’; bought by Dorothy Braude Edinburg, who gave it to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1998. The Saidenbergs acted as Picasso’s representative in the United States from 1955 to 1973. The first exhibition of Picasso’s works on paper at Saidenberg Gallery was in 1955 and this drawing did not appear in the catalogue.

4 Non-invasive analytical methods used include infra-red reflectography (IRR), macro-X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (MA-XRF), Reflectance Fouriertransform infra-red spectroscopy (R-FTIR) and hyperspectral imaging. 5 R . Raimondo: ‘Traduction et imaginaires du Canzoniere de Pétrarque, parcours comparés d’artistes et traducteurs: Glomeau et Feltesse, Aragon et Picasso, Bonnefoy et Titus-Carmel’, LEA: Lingue e Letterature D’Oriente e D’Occidente 8 (2020), pp.455–74. 6 For oil paintings, see M. McCully, ed.: exh. cat. Picasso: The Early Years 1892–1906, Washington (National Gallery of Art) 1997, pp.299–309; and A. Wallert, ed: Painting Techniques, History, Materials and Studio Practice, 5th International Symposium, 18th–20th September 2013, Amsterdam 2013, pp.258–63. For works on paper, see E. Braun and R. Rabinow, eds: exh. cat. Cubism: the Leonard A. Lauder Collection, New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 2014, pp.28–30; and A. Umland and B. Hartzell: Picasso: The Making of Cubism 1912–1914, New York, electronic publication, available at https://b-ok.cc/book/2630983/ d3f8a9?dsource=recommend, accessed 15th February 2022.

Picasso’s ‘Faun musician’

1947, a heavy cast shadow falls to the right of the pot.7 This dark triangular shape helps contextualise the dark form to the right of the vase in the now hidden Chicago drawing. Tapering to a point at the lower right corner of the IRR image this form can now be understood as representing the shadow cast by the vase.8

Between 1946 and 1948 Picasso frequently depicted compositions with flowers, often considered expressions of post-war optimism, in stark contrast with the tragic still lifes from the war period. The composition revealed with IRR imaging here seems unusual in its gestural detail and the relative naturalism of the treatment of the flower petals. Comparable compositions of the same period, such as those from his 1948 stay at the Atelier Madoura, show a much more synthesised treatment of plant structures.9

Further investigation with macro X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (MA-XRF) – a technique that maps the location of inorganic elements and thereby associated pigments present in a work of art – uncovered yet another, unknown earlier version of the vase of flowers, this one being the first composition Picasso drew on the blank page (Fig.8). This initial drawing consists of large flower heads with long, straight, spiky petals radiating out from the stem, held aloft beneath multiple criss-crossing stems and leaves, all set in an oval-shaped container. The flowers appear rendered in a more stylised manner than in the subsequent drawing, more in keeping with Picasso’s other still lifes of the period. Both of these new images clearly show that Picasso painted the background up to and around the flower forms.

Vase with foliage and three sea urchins (Fig.5), painted in Antibes the previous autumn, provides a clear comparison to these synthetic flowers with its linear petals, each applied with one stroke of paint, spreading out from the stem. The similar manner in which the background contours the still-life elements in both works should also be noted. Blue lines visible along the bottom edge of the first Chicago composition echo the vertical lines on the table of the Antibes painting. These represent a striped tablecloth or stylised drapery folds and bear a formal similarity to the striped shirt or dress in Head of a woman, which would have linked the still life and illustration visually within the book.

The vertical blue lines of the tablecloth in the initial composition, which extend out from under the final gouache layers down to the sheet edge, hold a clue to not only a diversity of themes but also a diversity of media. Evidence indicates that Picasso drew the first flower composition

7 Listed as stolen on the Interpol database in 2021. C. Zervos: Pablo Picasso, Paris 1965, XV, p.6, no.16.

8 A. Rickards: unpublished research report, 6th March 2012, Department of Prints and Drawings, Art Institute of Chicago.

9 Zervos, op. cit. (note 7), XV, p.6, no.15; p.48, no.81; and p.55, nos.97 and 98.

10 McCully, ed., op. cit. (note 6), p.300.

11 A .H. Barr, Jr: Picasso: Fifty Years of his Art, New York 1946, p.272.

12 ‘L’intérêt explicite d’Aragon pour Pétrarque dure une dizaine d’années’, F. Merger: ‘La réception de Pétrarque en France au XXe siècle: l’exemple

8. MA-XRF composite map of Fig.3, showing Prussian blue crayon (blue), gouache media containing titanium white (red) and cerulean blue gouache (green).

9. Raking-light image of the verso of Fig.3, flipped horizontally.

in coloured crayons, possibly with additions in coloured pencils. Stereomicroscope examination of the blue stripes reveals a high proportion of waxy binder present, while spectroscopic analysis (R-FTIR) detected kaolin, a commercial extender for crayons. A raking-light image of the verso (Fig.9) confirms this interpretation by revealing a dimensional impression resulting from the pressure Picasso applied with his crayon. The broad line width evident in both the raking-light and MA-XRF images corresponds with a crayon, while occasional narrower lines indicate Picasso then added details with finer-tipped coloured pencils or similar drawing implements. Pressing his crayon into the soft paper, Picasso drew synthesised spiky flowers with blunt, linear petals, then surrounded each bloom with a simple curving outline, best viewed in the raking-light image. He formed the stems, leaves and vase with similar broad crayon marks, arranged sideby-side in the wide stems and leaves at centre, as seen on the verso.

For his second iteration of the vase of flowers Picasso’s formal change to a more naturalistic style was accompanied by a change to gouache and black ink applied with a brush, the media used for The faun musician. The fine, black ink lines are clearly visible beneath the blue-grey gouache in the area of the chin and neck of the faun. The IRR imagery shows Picasso defined the irregular curving contours of each petal with thin black lines whereas he applied gouache more densely, perhaps layering on colour or indicating a more compact flower head. The flowers were rendered in vivid oranges and pinks, as evident through the cracks in the topmost layer. MA-XRF analysis and hyperspectral imaging allowed the authors to determine that some of the pigments used to paint the flowers contain titanium white, with a little vermilion and likely an organic red dye (the exact type remains unidentified). Then he contoured each flower with brilliant cerulean blue gouache containing titanium white and a calciumbased extender to fill in the background up to and around the still-life elements. The use of an aqueous gum binder was confirmed with R-FTIR.

d’Aragon’, Les annales de la société des amis de Louis Aragon et Elsa Triolet 10 (2005), available at http://www.louisaragon-elsatriolet. org/spip.php?article108, accessed 1st February 2022.

13 L . Aragon, transl.: Cinq sonnets de Pétrarque / avec une eau-forte de / Picasso / et les explications du traducteur, Paris 1947; see also Goeppert, op. cit. (note 2), p.130.

14 F.J. Jones: The Structure of Petrarch’s Canzoniere: A Chronological, Psychological, and Stylistic Analysis, Cambridge 1995, p.69.

Picasso’s gouache palette in the topmost layer, The faun musician, changes further, becoming customised. Here the artist combined the cerulean blue of the previous still-life background with Hansa yellow to render the green laurel leaves and he blended zinc white, titanium white, a touch of cerulean blue and carbon black for the blue-grey background. Picasso’s shift to muted hues of mixed grey and green for his final image lent the work a more contemplative atmosphere.

Picasso dated this work ‘7–11 Juin 47’, seemingly recording the time he spent developing the two still-life images and finally the faun. Published studies of his oil paintings document how Picasso frequently painted one composition directly over another without first painting out the earlier design. It has been postulated that as he transformed one image into another, Picasso maintained relationships between formal elements, aligning shapes and contours in the compositions, thereby facilitating the process of transformation.10 Picasso explained his process in a 1935 statement:

When you begin a picture, you often make some pretty discoveries. You must be on guard against these. Destroy the thing, do it over several times. In each destroying of a beautiful discovery, the artist does not really suppress it, but rather transforms it, condenses it, makes it more substantial. What comes out in the end is the result of discarded finds. Otherwise, you become your own connoisseur. I sell myself nothing.11

Close examination of the IRR image show similarities between the black ink lines of The faun musician and the still life. Picasso first painted over the still life with a semi-opaque blue-grey ground, leaving the earlier forms

partially visible. As he drew the faun, his organic, meandering lines echoed the curves of the flowers and leaves beneath, facilitating his transformation of flowers into faun. He positioned the faun’s head to cover the space taken by the clustered flowers. Intertwining lines defining the horns and eyebrows meet to form the nose precisely over the linear junction of multiple stems, thus repeating the ‘V’ shape from the design beneath. Picasso followed the sides of the vase when positioning the faun’s neck and aligned the chin and cheek with the horizontal water line in the vase. The faun’s uppermost proper right finger traces the curving top of the spiral at the base of the vase in the compositions beneath. That spiral shape recurs on the surface in the faun’s cheeks and chin, emphasising the inflated jowls blowing into the flute.

In addition to formal links between Picasso’s overlaid images, intellectual or emotional connections can also be suggested. Now that it is recognised as a decoration for a book, The faun musician and the underlying images can be considered within the physical and literary context of the volume to explore associations and meaning in each design.

Cinq Sonnets de Pétrarque falls within the decade 1941–51, when Aragon’s interest in Petrarch was at its height.12 It was published in 1947 as a limited edition of 110 copies: one hundred copies, numbered from 1 to 100 and ten copies, lettered from A to J.13 The sonnets are from Petrarch’s Canzoniere, in which he expressed his love for Laura de Noves and mourned her untimely death.14 The five sonnets that Aragon chose – numbers 1, 102, 176, 187 and 283 – all refer to Laura without ever mentioning her by name. Translating

10. Infra-red reflectogram (IRR) composite image of Fig.3 (1.5-1.73 µm).

11. Fig.10 with the black ink of the faun removed digitally, showing a vase of flowers beneath.

Picasso’s ‘Faun musician’

the line in poem 176 ‘Parmi d’udirla udendo i rami e l’ore’ with ‘Ce m’est l’ouïr ouïssant bruire l’aure/En la ramure’, Aragon uses French wordplay to evoke ‘Laure’, mimicking Petrarch’s use of this poetic device in sonnets that are not included in the translation. Although he translated and published the book anonymously, Aragon left hints to his identity by means of wordplay and references in the epigraph and introduction, and by the addition in his own handwriting of a proverb in lieu of his signature – unique to each work – below the colophon that concludes each copy. The handwritten text at the end of copy no.1 can be read as Aragon’s manifesto ‘There is no love but Elsa’s’ (‘Il n’est d’amour que d’Elsa’) (Fig.12) and reveals his overriding intention in publishing these translations: he wished to express his love for his wife, the Russian-born writer and translator Elsa Triolet (1896–1970), by freely translating the verses of the great Italian poet inspired by Laura, thereby placing his own verses on the Olympus of poetry. As Franck Merger has noted in an analysis of Aragon’s interest in Petrarch, the erasure of the name of Laura ‘permits the confusion between Laura and Elsa and between Petrarch and Aragon’.15 For Aragon, this symmetrical identification was the basis of the project.

In this context of blurred lines and multiple metamorphoses, Picasso used the same freedom when choosing a print to illustrate the work, by offering Aragon an etching, Woman’s head (Tête de femme), made two years earlier, on 9th January 1945. Aragon used his dedicatory and programmatic epigraph – ‘They said Laura was somebody ELSE’ (inscribed in English in the original text) – to hold a mirror to Laura, which reflects Elsa, and Picasso continued this play with mirrors on the following page (the epigraph is on the recto of the leaf preceding the etching) with his multifaceted intaglio illustration. There is a parallel here with the print dated 10th May 1945, also known as Woman’s head, that Picasso supplied as the frontispiece for Paul Eluard’s Á Pablo Picasso (1945), which was intended to represent the artist’s muse.16 The woman in both prints has features reminiscent of Françoise Gilot, an emerging artist whom Picasso had met in 1943 when she was twenty-two years old, and who moved in with him in 1946. By representing an idealisation of Laura, or Elsa as Laura, with the features of Gilot, Picasso further melds the identities of those associated with the publication.17

Upon opening the book and turning the first half-title page, The faun musician would have been viewed intimately by the reader. Imagined in this format, the faun’s rightward gaze and sloping shoulders direct the eye towards the title page and invite the reader to turn the page to read the epigraph, ‘They said Laura was somebody ELSE’, and then encounter Picasso’s illustration Head of a woman. These pages are followed by Petrarch’s verses and finally Aragon’s concluding proverb or aphorism. The physical format of the book and the act of turning the pages further link the poets, the artist and the reader through the visual and literary themes of love, loss, lust and longing.

Neither the vase of brightly coloured flowers that Picasso first considered for the book’s frontispiece, nor the faun that replaced it, has any obvious connection with the book’s contents: the sonnets chosen by Aragon include no mention of either flowers or fauns. This was not unusual for the artist, as Picasso himself in 1961 adamantly refused the facile reading of his creations for books as illustrations.18 If he had allowed the flowers, whether in the drawn and painted versions, to remain, they would have suggested renewal and regeneration. That would have been

15 ‘Cet effacement du nom permet la confusion entre Laure et Elsa et entre Pétrarque et Aragon’, Merger, op. cit. (note 12).

16 C. Stuckey: ‘The face of Picasso’s lithography’, in J. Richardson and F. Gilot: exh. cat. Picasso and Françoise Gilot: Paris-Vallauris, 1943–1953, New York (Gagosian Gallery) 2012, p.174.

17 Goeppert, op. cit. (note 2), p.130.

18 ‘I never actually illustrated anything. I created book engravings that were added to texts, to which they bear some kind of resemblance’, Picasso quoted in J-Y Sudor: ‘The elsewhere of the text: illustrated books’, in Musée National Picasso, P. Picasso, and A. Baldassari: Musée Picasso Paris

appropriate for not only a period of post-war optimism but also for a happy time for Picasso personally, following his son’s birth. By contrast, The faun musician, while seemingly simple, combines complex references, identities and allusions. For example, Picasso surrounded the faun’s head with laurel leaves, perhaps in order to evoke the way that Petrarch (like Dante before him) was often portrayed with a laurel wreath as Italy’s poet laureate. Within the context of the book, therefore, laurel leaves can be understood as symbols of genius and immortality that from Antiquity to the present day have associated great men across time and space and here connect Petrarch, Aragon and Picasso.

It may be possible to map the replacement of the flowers by the faun against Picasso’s movements between 7th and 11th June 1947, the dates he gave to The faun musician. In the course of June, Picasso, Gilot and the newly born Claude left Paris for Golfe-Juan, on the Côte d’Azur, arriving at a date given variously in the published chronologies of Picasso’s life as midor late June.19 Yet although in his 1956 catalogue of Picasso’s watercolours and gouaches John Richardson listed the work as ‘executed Paris, June 7th–11th, 1947’ (a book possibly written in collaboration with Picasso and published only nine years after the drawing was made),20 it is conceivable that the couple arrived in Golfe-Juan much earlier than has been thought, between 7th and 10th June.21 A clue to this possibility can be found in a note in Henri Matisse’s diary in the Archives Matisse, which records that he visited Picasso in Golfe-Juan on 12th June.22 The trip from Paris to the South of France, travelling with an infant baby, would have been arduous to undertake in a single day, an inference corroborated by some sources that mention a stop in Avignon.23 One could also imagine Picasso and Gilot would not have wanted to receive Matisse on the day of their arrival in the South. They might have needed some time to settle before receiving guests in the house where they were staying, the villa of Picasso’s printer Louis Fort, which Picasso had rented the year before, when he drew a number of fauns’ heads (Musée Picasso, Antibes).24

It is tempting to speculate, therefore, that Picasso drew the first still life in crayon in Paris on 7th June and then painted a more elaborate bouquet of flowers using gouache and black ink sometime later and then, after arriving in Golfe-Juan, he repainted the composition as a faun’s head playing the diaule or double flute. One last faun was born in Golfe-Juan in that year, when on 22nd June Picasso executed the aquatint Faun with a double flute and a reclining woman 25 By 25th June he was back in Paris.

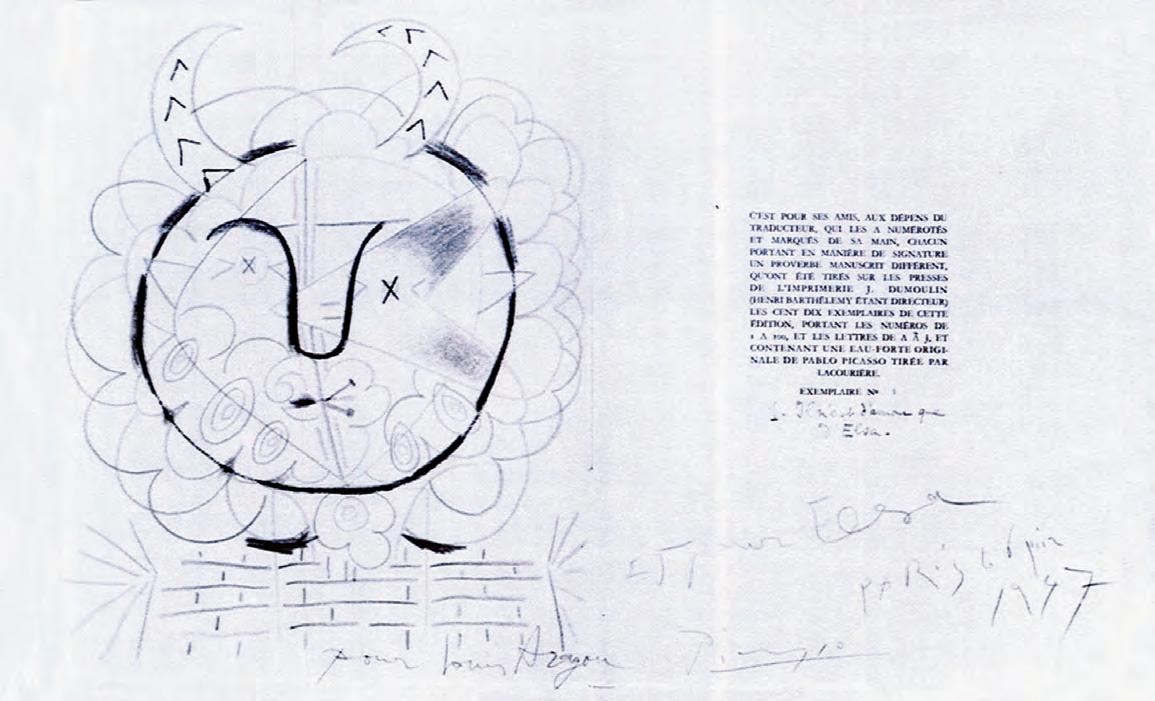

A deeper understanding of The faun musician is provided by another drawing. On 6th June 1947, the day before starting The faun musician, Picasso drew another faun’s head on the colophon pages of copy no.1 (Fig.12).26 It is a very different image, for which he used only crayon. On a base rendered like a brick wall, he first started to draw flowers with their stems, petals and stamens in pink and yellow. Then, with a marked change of direction, he added a red-and-black circle for the shape of a face, a black continuous line for the eyebrows and the nose (a mark he had regularly used in his faun drawings in the previous summer),27 and two horns on the forehead, so transforming the bouquet into a Faun’s head and the base into the chest of the figure, echoing the metamorphosis from plant to faun that took place for The faun musician. Below the drawing he wrote ‘pour Louis Aragon’, adding on the opposite page to the right ‘Et pour Elsa Paris 6 juin 1947 Picasso’. Aragon’s unique handwritten proverb appears following

Collection, Paris 2014, p.285.

19 F. Gilot: Matisse and Picasso: A Friendship in Art, New York 1992, p.63; and E. Cowling et al.: exh. cat. Matisse Picasso, Paris (Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais), London (Tate Modern) and New York (MoMA) 2002–03, p.386.

20 Picasso and Richardson, op. cit (note 1), no.31.

21 Rafael Inglada to Jean-Louis Andral, email communication, 24th–25th August 2020 and 30th January 2022.

22 E. Cowling et al., op. cit (note 19), p.386.

23 ‘L’été venu (1947), tout le monde repart pour Golfe-Juan. Pablo, qui s’est arrêté quelques jours à Avignon,

Picasso’s ‘Faun musician’

the edition number, ‘Il n’est d’amour que d’Elsa’.28 Although the 6th June drawing appears to have been done quickly, almost as a sketch, the use of crayon may also suggest a link with the first vase of flowers made on the frontispiece with coloured crayons. Perhaps the genesis of the faun drawn in Paris on 6th June, far away from the natural and mythological Mediterranean environment of its predecessors made on paper in GolfeJuan the previous summer, had left Picasso with the desire to renew his engagement with the motif following his journey to the Côte d’Azur, prompting him to start the new composition in gouache that would become The faun musician.

Unravelling the evolution of the imagery illuminates the close connection between making and meaning in this work: between Petrarch’s text, its metamorphosis through Aragon’s selection and translation and the transformation of the visual representations Picasso chose to decorate and personalise the blank front page. The discovery of the depictions of flowers underlying the faun musician – the earliest of which was made in crayons – means that is possible to make a compelling connection with the 6th June crayon drawing of a faun, Head, also begun as a flower bouquet, inscribed to Aragon and Triolet on the copy no.1 of the limited edition, which the artist offered as a dedicated, personalised copy to the couple. It is not known to which numbered copy the Chicago folio belonged to, nor is it known for whom Picasso intended it – he may perhaps have kept it

retrouve peu après les siens’, in P. Cabanne: Le siècle de Picasso, II: 1937/73, Paris 1975, p.159.

24 Musée Picasso, Antibes, inv. nos. MPA 1946.2.1, MPA 1946.2.2, MPA 1946.2.3, MPA 1946. 2. 4, MPA 1946.2.5, MPA 1946.2.6, MPA 1946.2.7.

25 B. Baer: Picasso Peintre-Graveur: Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre gravé et des monotypes 1946–1958 Berne 1988, IV, no.789, p.86.

26 For a colour image of the drawing without the colophon, see Sale, ‘Impressionist and Modern Art, part II’, Sotheby’s, New York, 13th November 1997, lot 476, p.265. Because the catalogue description includes the full dedication to Aragon and Elsa and

12. Head, 6 June, 1947, by Pablo Picasso. 1947. Coloured crayon on the page opposite the colophon of the book Cinq sonnets de Pétrarque / avec une eau-forte de / Picasso / et les explications du traducteur, each page 33.4 by 25.7 cm. (Private collection).

for himself, thereby creating mirrored personalised books for himself and Aragon, each decorated with flowers transformed into a faun.

Given that Picasso’s depictions of fauns, traditionally understood as untamed and libidinous, have usually been understood as self-referential, or alter egos, his drawings in Cinq sonnets de Pétrarque may have been intended to make a humorous or even subversive contrast between his approach to relationships with women and Aragon’s Petrarchan ideal of chaste and perpetual love. It is perhaps significant that, according to Gilot, Picasso was baffled by the cult Aragon made of Elsa.29 Yet the new discoveries about the Chicago drawing indicate that Picasso also drew upon the concept of transformation to conflate his own identity with those of several creative collaborators, including the fourteenth-century poet, Petrarch, his love, Laura, the modern poet Louis Aragon, his wife, Elsa Triolet, and Françoise Gilot. Contextualisation of these new findings convincingly brings the influential role of the artists’ muses – Laura for Petrarch, Elsa for Aragon, Françoise for Picasso – to the fore. The deceptively modest image ultimately condenses multiple references at once classical, literary and personal.

notes the number 1 in the colophon, it can be assumed the whole folio was sold, even though the dimensions cited (32.7 by 24.8 cm.) – like those with which the Chicago Faun musician was originally published in 1957 – refer only to the page with the faun drawing. The provenance is listed as Jane Kahan, New York.

27 See, for example, the Faun in the collection of the Musée Picasso, Antibes, inv. no.MPA 1946.2.7. 28 Goeppert, op. cit. (note 2), p.130.

29 F. Gilot and C. Lake: Life with Picasso [1964], ed. Harmondsworth 1966, pp.267–68. We thank the anonymous reviewer for drawing our attention to Gilot’s comment.