4 minute read

Il Mobile a Roma dal Rinascimento

southeast wall and the other part on the northeast wall.

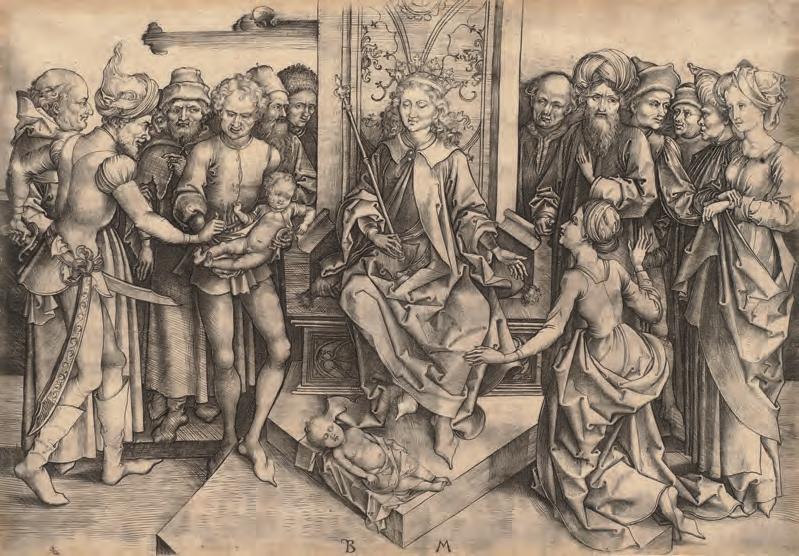

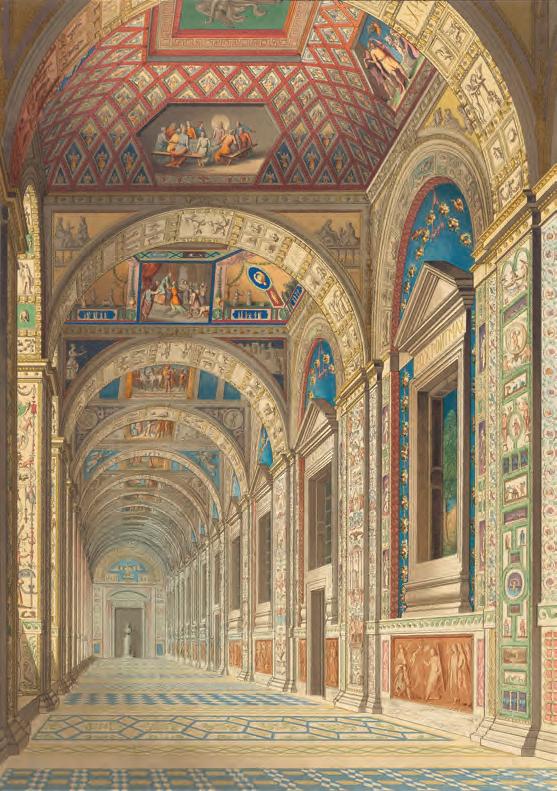

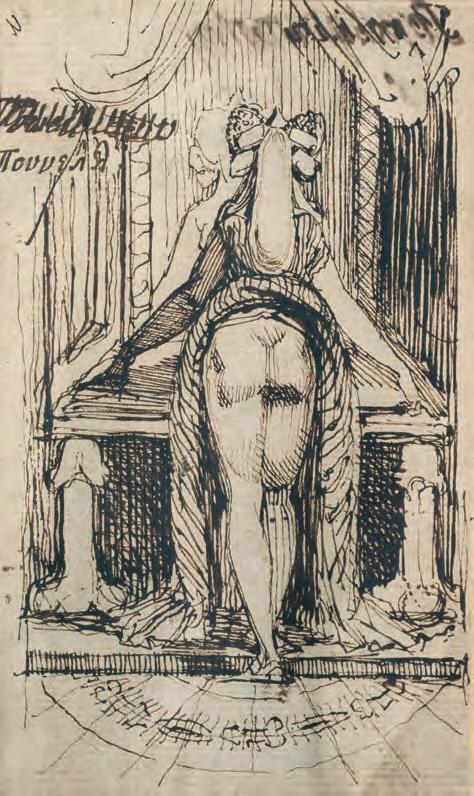

The display in the hall contains a screen with a digital presentation of the paintings, which visitors can use to navigate and magnify the images, as well as a judicious selection of Pisanello’s drawings and medals. Like the digital images, these smaller works encourage close inspection, which reveals numerous affinities between the loans and the murals; for instance, in terms of its physical and emotive qualities, as revealed in the subject’s downcast eyes, the graceful Woman’s head in profile (cat. no.II; Fig.8), a fragment of a wall painting, can be compared to the portrait of the princess in the fresco on the northeast wall. A detailed study of Gothic crenelated battlements and towers in brown ink (c.1435; Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF519 verso) and the elaborate redchalk castles on the northeast wall demonstrate Pisanello’s interest in architectural details. An exquisite drawing of an Estense knight as falconer (c.1440; Fondation Custodia, Paris; no.XII), wearing an extravagant broad-brimmed headdress, closely compares in his posture and attire to a male figure in the tournament sinopia that has been removed from the wall and is exhibited in the adjacent Sala dei Papi (no.III). The figure has sometimes been identified with Gianfrancesco I Gonzaga (1395–1444), Marquess of Mantua and the patron of the work. In an example of what Andrea de Marchi describes as Pisanello’s ‘irregular wit’ (p.60), the artist contrasts the elegant and dignified bearing of this figure with a diminutive knight also wearing ornate headgear, who charges into the uproar in the lower half of the tournament fresco.

Advertisement

These skilfully curated connections help to answer some of the scholarly questions concerning the dating and unfinished state of the cycle. As Andrea de Marchi argues in the catalogue, the woman’s head in profile may be a fragment from Pisanello’s lost fresco cycle in the Lateran, Rome, which supports the dating of the Mantuan paintings to shortly after Pisanello’s return from Rome in 1431.4 The meticulously drawn profile-portrait of Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg (1432–33; Louvre; no.IX) contains the artist’s precise notes on the colouration of the subject’s beard and eyes. The drawing provides a reminder of the emperor’s visit to Mantua in 1433 to confer the marquisate on the house of Gonzaga. As Michela Zurla argues, the deadline set by the esteemed guest’s arrival at the Gonzaga court might explain why Pisanello terminated (or rushed to finish) the painting in the court apartments.

By bringing the Mantuan cycle and Pisanello’s graphic work together, the exhibition also raises the question how the court artist’s frescos might have been viewed by his princely

8. Woman’s head in profile, by Pisanello. 1430–35. Detached wall painting, 24 by 17 cm. (VIVE – Vittoriano e Palazzo Venezia, Rome; exh. Palazzo Ducale, Mantua).

9. Detail from Tournament of knights, by Pisanello. 1430–33. Fresco. (Palazzo Ducale, Mantua). patrons and their humanist advisers in the early fifteenth century. As Michael Baxandall argued in the years the paintings in the Palazzo Ducale were being uncovered, the ‘relative importance of drawing and fresco’ within Pisanello’s œuvre could be seen to be ‘reversed [so] that the role of the fresco included that of reproduction, for a mass audience and in a coarser medium, of a selection of popular themes from his work – Highlights from Pisanello’. Fresco was a convenient medium in which to showcase the ‘distinctive quality and range of Pisanello’s performance’ as an artist.5 His skills, so evident in his drawings and in his later production as a medallist, could thus be transferred to a large scale. Why else might Pisanello have been set (or set himself) the virtually impossible task of completing the vast commission ‘free hand’, without using a sinopia as a guide, as though it were a grand exercise in panel painting? Bravura pieces, such as the knight who gazes out at us from the medieval tourney (Fig.9), were designed for recognition.

The exhibition includes rooms on the piano terra of the palace dedicated to the arts in Mantua in the early fifteenth century, which seek to contextualise Pisanello’s creation. They include such important loans as the Virgin and Child with saints Anthony Abbot and George (c.1440; National Gallery, London; no.III) but they lead the visitor away, both physically and conceptionally, from the exhibition’s main focus. Given the close relationship between Pisanello’s mural and panel painting, it would have been better to have placed the panels alongside the drawings and medals in the Sala dei Pisanello. This does not detract from the success of the exhibition. Il Tumulto del Mondo goes some way to fulfil the wishes of Paccagnini, so that future visitors to Palazzo Ducale now have a reason to linger over Pisanello’s great cycle.

1 G. Paccagnini: exh. cat. Pisanello alla corte dei Gonzaga, Mantua (Palazzo Ducale) 1972, p.5. 2 Reviewed by Maria Fossi Todorow in this Magazine, 114 (1972), pp.886, 888 and 891. 3 Catalogue: Pisanello: Il Tumulto del Mondo. Edited by Stefano L’Occaso. 176 pages incl. 160 col. + 28 b. & w. ills. (Electa, Milan and Rome, 2022), €30. ISBN 978–88–928–2318–1. 4 See also A. de Marchi: ‘Reconsidering the traces of Gentile da Fabriano and Pisanello in the Lateran Basilica’, in L. Bosman, I.P. Haynes and P. Liverani, eds: The Basilica of Saint John Lateran to 1600, Cambridge 2020, pp.379–99. 5 M. Baxandall: ‘Guarino, Pisanello and Manuel Chrysoloras’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 28 (1965), pp.183–204, at p.194.

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 10th October 2022–8th January 2023

by elizabeth goldring

This landmark exhibition, the first in the United States to be devoted to the art of the Tudor courts, begins with a bang. The first objects encountered upon entering the installation are three monumental bronze sculptures: two angels bearing candlesticks (cat. no.16; Fig.10), plus a candelabrumcum-pillar set on a marble base,