38 minute read

The many faces of Mary Magdalene by susan haskins

stating that any identification of a new portrait representing Isabella must be based on one of the securely identifiable works. Of these, the most secure is the portrait of Isabella in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (Fig.12).45 This work has been variously attributed to Bronzino, to his school or considered a copy after an autograph work by him.46 The painting’s condition is poor, with significant losses, possibly the result of damage during a fire, with large areas of infill and retouching, even after its most recent conservation in 1997.47 Unfortunately, no technical photographs were taken during that campaign that might offer further evidence regarding its attribution. Still, its quality is very high, with some beautiful passages of original painting surviving, such as the lace of the partlet and in the features of the sitter, including the ringlets of hair along the sides of her forehead in front of her ears. Following a recent examination of the painting, and considering its damaged state, the present author would argue that there is no reason to exclude it from Bronzino’s œuvre.

Advertisement

The question of the Stockholm portrait’s attribution is not irrelevant to the questions at hand. Several of the same pictorial strategies have been used by the painter in both works. In particular, the hairline of the girl seen in each painting runs across her forehead, with a parting in the centre. The sides of the forehead and the ears are framed by round curls, which appear to be painted with a very similar technique, in which the artist drew the butt end of the brush through the curls to help define their forms, highlights and shadows. As far as we can tell from her portraiture, Eleonora did not style her hair this way at any point in her lifetime, instead keeping her hair pulled tightly back and kept in a snood. Although a fashion for such ringlets began in the 1550s48 – the Turin Lady offering just one example – the portrait in Stockholm may actually predate that trend. As this feature appears to be recognisable in all the reliable portraits of Isabella, it can be argued that it was a characteristic of her hair, which may have been naturally curly, resisting being tamed into the perfectly coifed style preferred by her mother. The colour of the hair in both portraits tends towards red, with the somewhat abraded hair in the Stockholm portrait appearing a slightly lighter shade. Other features of the two portraits also accord well for the identification of the Lady in black as Isabella. In all the

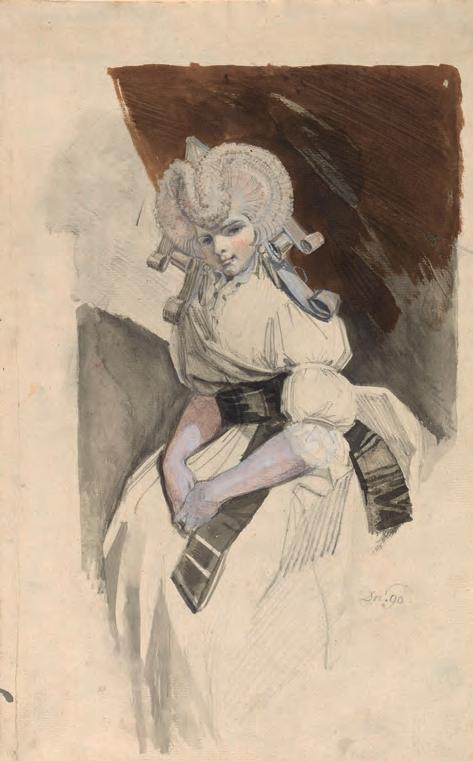

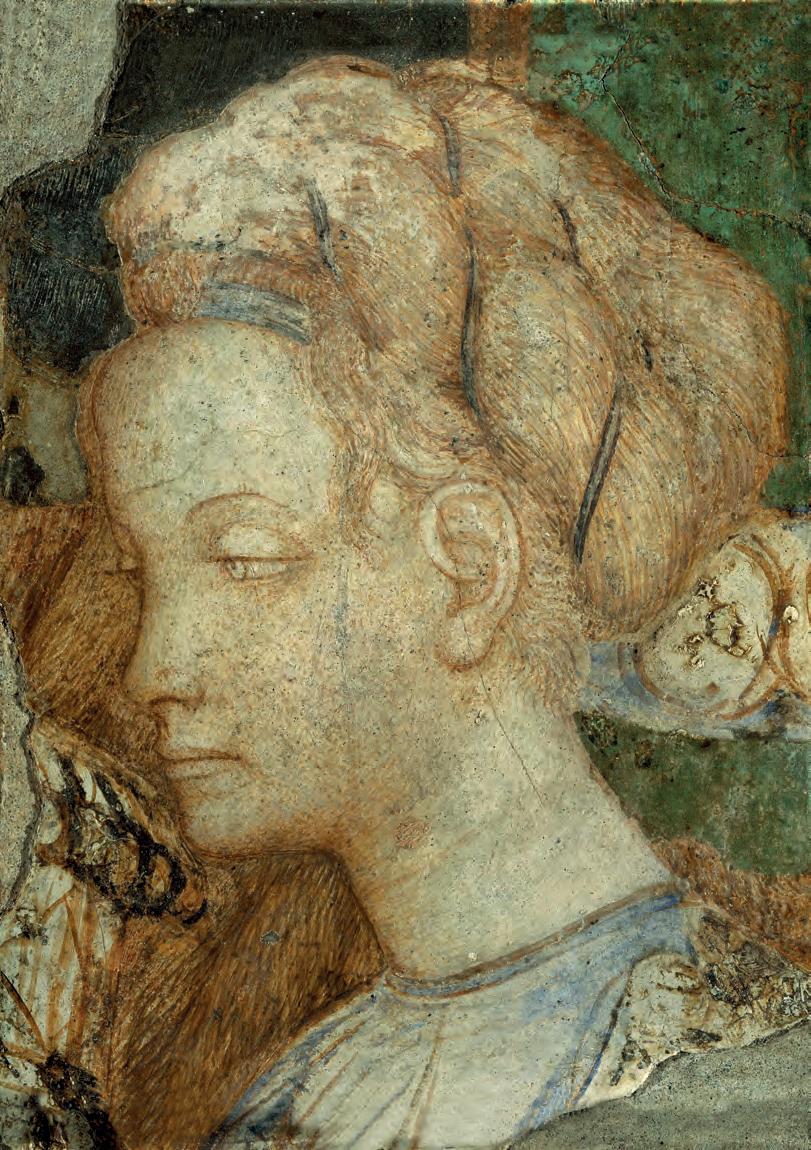

11. Portrait medal of Isabella de’ Medici Orsini, by Domenico Poggini. 1560. Bronze, diameter 4.9 cm. (Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence). 12. Isabella de’ Medici as a young girl, by Agnolo Bronzino. c.1553. Oil on panel, 44 by 36 cm. (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm).

45 On the portrait, Nationalmuseum inv. no.NM37, see the entry by J. Eriksson in S. Norlander Eliasson et al., eds: Italian Paintings: Three Centuries of Collecting, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Ostfildern 2015, I, pp.248–51, no.99. 46 Bernard Berenson first attributed the portrait to Bronzino but later attributed it to his workshop. See A. Emiliani: Il Bronzino, Busto Arsizio 1960, p.72, as by Bronzino; E. Baccheschi: L’opera completa del Bronzino, Milan 1973, p.109, no.171, as likely connected to the series of miniature portraits on tin attributed to Bronzino and his workshop; Langedijk, op. cit. (note 43), II, p.1095, no.63,5, as school of Bronzino; Langdon, op. cit. (note 41), pp.109–10, 116, and fig.32, as after Bronzino; Eriksson, op. cit. (note 45), as attributed to Bronzino; and D. Gamberini: New Apelleses and New Apollos: Poet-Artists around the Court of Florence (1537–1587), Berlin 2022, pp.107–08, fig.9, as workshop. 47 On the condition of the work and its conservation history, see Eriksson, op. cit. (note 45), p.248. At the Nationalmuseum, the author would like to thank Carina Fryklund, Curator of Old Master Paintings, Drawings and Prints before 1700, for facilitating his research and Lena Dahlén, Paintings Conservator, for kindly sharing information available in the museum’s files. 48 Orsi Landini, op. cit. (note 31). 49 Eriksson, op. cit. (note 45), p.250. The contract for the betrothal was signed on 11th July 1553; Goldenberg Stoppato, op. cit. (note 43), p.313. 50 B. Edelstein: ‘“La fecundissima Signora Duchessa”: the courtly persona of Eleonora di Toledo and the iconography of abundance’, in K. Eisenbichler, ed.: The Cultural World of Eleonora di Toledo: Duchess of Florence and Siena, Aldershot 2004, pp.71–97. See also Langdon, op. cit. (note 41), pp.116 and 163. 51 Paolo Giordano was originally offered a choice between Isabella and Lucrezia but opted for the elder of the two sisters. The relationship was remarkably felicitous, as documented by their unusually affectionate

A Bronzino portrait of Isabella de’ Medici Orsini

reliable portraits of Isabella, the corners of her mouth turn up past the fleshy portions of her lips. The upper lip has a pronounced Cupid’s bow shape, with a strongly modelled philtrum below the nose. The chin is straight, not cleft, and certainly not receding. The eyes are brown, while the shapes of the eyelids and opening of the eyes, and the forms and colouration of the brows and lashes, are comparable in both works. Undoubtedly the greatest distinction between the physiognomy of the Stockholm Isabella and the Lady in black is her nose. In the latter, the sitter has a significant nose that juts out and descends slightly, casting a shadow over the upper lip.

It has been reasonably suggested that the Stockholm portrait was commissioned at the time of Isabella’s betrothal to Paolo Giordano Orsini in 1553 as a gift for him.49 The cornucopia-shaped earrings she wears were thus intended to suggest her potential fertility, in addition to connecting her to an iconography of abundance closely associated with her mother, who had already borne ten children by March of that year.50 Whereas portraits of their male children were all commissioned from very young ages, the only portrait of one of the female children initially requested by Cosimo or Eleonora was that of the eldest daughter, Maria. This was probably because Maria was destined from a young age for a prestigious marriage to Alfonso II d’Este, the future duke of Ferrara. When she died prematurely, she was replaced by her younger sister Lucrezia, Isabella in the interim having been chosen by Orsini as his bride.51 This too would seem to confirm that the Stockholm portrait of Isabella was commissioned following her betrothal. No portraits of Lucrezia, for example, appear to have been painted prior to her marriage to Alfonso in 1558.

Isabella was the third child, born in August 1542, and would therefore be about eleven years old in the Stockholm painting. In a portrait painted c.1560 she would have been around eighteen. If she is the sitter in the Portrait of a woman in black, it is possible that the large nose seen in that work was a more recent development in her physiognomy, having emerged during puberty. Confirmation of this is provided by another reliable source for her iconography, the portrait medal of her and her husband by Domenico Poggini, cast precisely in 1560 (Fig.11). Allowing for the differences in scale and media, and the profile pose preferred in medals, one can confirm several aspects of Isabella’s appearance as recognised by contemporaries: the prominence of her nose, the shape of her chin and even the curls descending along the side of her face.52 We may also note that she appears surprisingly matronly for a woman of eighteen. This accords with the mature appearance of the sitter in the Lady in black, which is appropriate for the gravitas of the aristocratic subject, as well as reflecting the generally more adult appearance of youth in sixteenthcentury portraiture.

For the sake of brevity, it is not possible to compare the Lady in black with each of the portraits currently identified as depicting Isabella. However, it is worth considering one more example, a

correspondence; see E. Mori, ed.: Lettere tra Paolo Giordano Orsini e Isabella de’ Medici (1556– 1576), Rome 2019. 52 The prominent nose and curls of hair along the side of her forehead also appear in a later portrait of Isabella, formerly at Schloss Ambras and now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. See Langedijk, op. cit. (note 43), II, p.1092 fig.63,3; and Langdon, op. cit. (note 41), p.149 and fig.46. 53 However, for the intriguing suggestion that the work should be attributed to a lesser-known student of Bronzino, Alessandro Pieroni, see Goldenberg Stoppato, op. cit. (note 43), p.318. 54 Langedijk, op. cit. (note 43), II, pp.1093–94, fig.63,4; and Langdon, op. cit. (note 41), pp.157–59. 55 ASF, GM 28, published as C. Conti: La prima reggia di Cosimo I de’ Medici nel Palazzo già della Signoria di Firenze descritta ed illustrata coll’appoggio d’un Inventario inedito del 1553 e coll’aggiunta di molti altri documenti, Florence 1893. painting usually attributed to Alessandro Allori (Fig.13).53 Allowing for distinctions in the quality of the two portraits, and the greater level of abstraction in the Palazzo Pitti painting, it can be seen that that the nose is nonetheless important, and that its tip descends over the upper lip, which is of a prominent Cupid’s-bow shape with the philtrum in strong relief. The sides of the mouth curve up, the chin is similarly shaped and the hairstyle displays the strong central parting, straight brow line and descending ringlets. The many surviving replicas and variants of the Palazzo Pitti portrait suggests its success with the sitter, who may well have appreciated the flattering idealisation of her distinctive features.54

The 1560 inventory offers few clues to confirm that the work listed in it is the Lady in black. Unlike some registers, this one does not include the size of the works. However, the work described in 1560 is clearly identified as having been painted by Bronzino. An analysis of numerous Medici Guardaroba registers covering a significant period of time offers some confirmation that this identification is reasonable. No portrait of Isabella is recorded in the Medici Guardaroba prior to 1560. This is perhaps surprising, given the likelihood that the Stockholm portrait was executed c.1553. A major and well-studied inventory of Palazzo Vecchio was taken in that year.55 Nor is the painting described in any of the subsequent Guardaroba registers documenting additions to the Medici collections between 1553 and 1560. This suggests that

13. Portrait of Isabella de’ Medici Orsini, by Alessandro Allori. After 1560. Oil on panel, 99 by 70 cm. (Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence).

the Stockholm painting never entered the Guardaroba but was sent directly to Orsini in Rome immediately upon its completion. This hypothesis would seem to be confirmed by the lack of replicas of it in Florence,56 and may be further supported by the fact that the wellknown portraits of Isabella’s siblings as children are generally clustered together in the inventories and specified as having been made ‘when he (or she) was little’.57

The reference to the portrait of Isabella by Bronzino in the 1560 register thus likely records a work that had just been executed and consigned to the Guardaroba. Confirmation for this may be provided by comparison with another register compiled at the same time, which makes clear that both inventories were ordered to take stock at the end of the tenure of Mariotto Cecchi as guardarobiere. In the ‘Spoglio’ (compendium) of the registers kept by Cecchi through to the end of his administration, on 17th August 1560, there is no reference to a portrait of Isabella, although many of the same paintings are recorded in both this volume and the 1560 inventory.58 The inventory in which Bronzino’s portrait appears was compiled under the supervision of the ducal Depositario Generale Antonio de’ Nobili and was begun on 1st July 1560.59 This means that the painting was completed in the second half of the year.

The painting appears again in only one other inventory in which the keeper of the Guardaroba also registered the consignment of objects, usually indicating their destination and use, for example as gifts, for display in one of the ducal residences or as models lent to artists to make replicas.60 However, the departure of the painting from the storage areas of the Palazzo Vecchio is not recorded there. Still, it must have been removed because it does not appear in subsequent registers, suggesting that it remained only briefly in the storage areas of the Palazzo Vecchio.61 Isabella resided almost exclusively in Florence following her marriage, except for a brief period in Rome, which apparently she disliked.62 In her absence, she sent several portraits of herself to her husband in Rome. Paolo acknowledged the receipt of one of these in 1562.63 This could well be Bronzino’s portrait, so soon after it was presumably executed. If the work was sent to Rome, this would help to explain why it subsequently disappeared. Sometime after Isabella’s death in 1576, Orsini consigned her portraits to a convent, possibly to prepare his Roman palace to welcome his mistress and later second wife, Vittoria Accoramboni.64 One of Bronzino’s portraits of Isabella may have been among these, although both may have ultimately found their way onto the Roman art market by a similar route. The Stockholm painting has a documented Roman provenance from the collection of the sculptor Johan Niklas Byström, who probably acquired it around 1825 while living in the city.65 The Scottish provenance for the later portrait suggests that it too was purchased in Rome during the slightly later residence of the 8th Earl of Northesk.

The consummation of Isabella’s marriage in 1558 would have been a possible motivation for commissioning a portrait of her from Bronzino. However, another more likely reason occurred in October 1560, when Orsini’s title was upgraded to Duke of Bracciano, following negotiations with Pope Pius IV that were already under way by June of that year. This was what inspired the production of Poggini’s medal.66 Bronzino’s reliance on a portrait type invented for Eleonora, then, was not simply a rhetorical device but a pictorial choice made to celebrate Isabella’s new status as a duchess. This may also explain why he opted for another change to his initial composition, visible in the X-radiograph of the painting (Fig.14). He originally depicted Isabella’s sleeves as attached to her bodice by bows, which were then eliminated and substituted with gold clasps. The choice simplified the contour of the costume, making it appear less fussy and less youthful, more appropriate to a mature woman who was prepared to lead as a head of state. Similar clasps appear on the bands joining the sleeves to the bodice of Eleonora’s more elaborate costume in the Uffizi portrait, in both cases a luxury accessory that emphasised the sitter’s status.

For one of these two occasions, in either 1558 or 1560, the court intellectual Benedetto Varchi, a close friend of Bronzino, wrote a sonnet in celebration of Isabella and her military husband, ‘Nuova casta Ciprigna e nuovo Marte’ (‘New chaste Cypris and new Mars’). The poem is well known to art historians for Varchi’s celebration of Bronzino’s ‘educated pen being equal to his erudite brush’, a reference to the artist’s exceptional talents as both painter and poet.67 Varchi’s poem has been studied by numerous scholars, who have attempted to connect it to

56 Eriksson, op. cit. (note 45), pp.249–50, notes the existence of a copy in a private collection. However, this would seem to be a nineteenthcentury replica by the German painter Friedrich Müller, whose signature may be on the reverse. 57 In ASF, GM 65, fol.162 left, the portrait of Isabella immediately follows ‘Un ritratto dell’Illustrissimo principe [Francesco]’ and ‘Un ritratto dell’Illustrissimo Signor Don Gratia [Garzia]’, both of which are specified as depicting them ‘quando era piccolo’, in addition to recording that they were ‘di man del Bronzino’. 58 ASF, GM 46. 59 ASF, GM 45. 60 ASF, GM 65. 61 A painting that was either the Stockholm portrait or a related work is recorded once, in one of the 1570 inventories; see ASF, GM 75, fol.62 right: ‘Uno quadro con hornamento di nocie della signora donna Isabella quando era banbina’. In another copy of the inventory taken the same year, the painting is specified as a ‘quadretto’, which may suggest that it was a now-lost replica executed for the miniature series of portraits on tin produced by Bronzino and other members of his workshop; see ASF, GM 73, fol.45 left. 62 A. Amendola: Gli Orsini e le arti in età moderna: collezionare opera, collezionare idee, Milan 2019, p.135. On her distaste for the Orsini castle in Bracciano, see Murphy, op. cit. (note 34), pp.82–85. Isabella travelled to Rome on three occasions: in the train of her parents, for their reception by the Pope in 1560; with her father again in 1570, for his elevation to the title of Grand Duke; and for the start of the Holy Year in 1575. See B. Furlotti: A Renaissance Baron and his Possessions: Paolo Giordano I Orsini, Duke of Bracciano (1541–1585), Turnhout 2012, p.13, note 36. 63 Ibid., p.16. 64 Furlotti records three portraits of Isabella consigned to the Roman convent of Torre de’ Specchi, documented in inventories taken after Orsini’s death in 1585, Furlotti, op. cit. (note 62), p.16, esp. note 51. Already in February 1556, during his first trip back to Rome after his transfer to the Medici court in Florence, Paolo begged Isabella to send him her portrait, see Mori, op. cit. (note 51), pp.63–64. 65 Eriksson, op. cit. (note 45), pp.248–49. On Byström and his collection, see also S. Ekman: ‘The collecting sculptor: the rediscovered paintings from the Byström Collection in the Nationalmuseum’, in Norlander Eliasson, op. cit. (note 45), pp.233–47. 66 Murphy, op. cit. (note 34), pp.78–79. 67 For Varchi’s poem and Bronzino’s reply, see Gamberini, op. cit. (note 46), pp.207–08, lines 14–15; and A. Geremicca: Agnolo Bronzino: “La dotta penna al pennel dotto pari”, Rome 2013, p.257, LXV–LXVI: ‘la dotta penna al pennel dotto pari’. 68 See, among others, M. Rossi: ‘“… that naturalness and Florentinity (so to speak)”: Bronzino: language, flesh and painting’, in Falciani and Natali, op. cit. (note 11), pp.177–93, at p.177; Gamberini, op. cit. (note 46), pp.107–108. See Geremicca, op. cit. (note 67), pp.74, 94–95, 173 and 175; and D. Parker: Bronzino: Renaissance Painter as Poet, Cambridge 2000, pp.87–88. 69 ‘Farne doppia potete eterna storia’; ‘ond’a doppio per voi l’Arno si gloria’. 70 As Furlotti notes, the portrait sent by Isabella to Paolo Giordano in 1562 was intended to be part of an exchange. On 18th October he wrote to Isabella acknowledging the receipt of her portrait; on 19th October he wrote again, promising to send one of himself soon, stating, ‘Every night I sleep with your portrait and it is most dear to me’; Furlotti, op. cit. (note 62), p.16, note 50 (translation by the author), p.186; for complete transcriptions, see Mori, op. cit. (note 51), pp.129–33. The deaths of two of Isabella’s brothers and her mother in the following months may have interrupted the project to commission a pendant portrait. 71 Gamberini, op. cit. (note 46), pp.108–09. It is especially relevant that the example of a recusatio by Bronzino in response to a sonnet written by another contemporary, Gherardo Spini, belied his feigned inability to rise to the challenge posed by Spini regarded his famous portrait of Laura Battiferri. That painting is generally dated to 1560, see Siemon, op. cit. (note 36). Thus, the production of the two portraits and the two poetic exchanges would have been exactly contemporary. 72 Orsini was also close to Varchi, who began but left unfinished a series of unpublished poems dedicated to the 1558 consummation of the marriage to Isabella. Varchi also

A Bronzino portrait of Isabella de’ Medici Orsini

the production of a double portrait of Isabella and Orsini.68 However, the references in the sonnet to something ‘double’ are not to a double portrait but to Bronzino’s unique ability to depict with both pen and brush, with which ‘you can make eternal history double’ and ‘for which the Arno glories doubly for you’.69

Varchi’s poem is couched as an incitement to Bronzino to depict the young couple, possibly in a pair of pendants of which only the portrait of Isabella was completed.70 In her recent study of poet artists at the Medici court, Diletta Gamberini has observed that poems like Varchi’s were often ex post facto creations to celebrate a work already executed or underway.71 Isabella was considered particularly erudite and had close ties to Varchi’s literary circle.72 Indeed, the book she holds in the portrait, given its size and the nature of its binding, with the charming grotesque mask clasps that hold it shut, is very likely to have been understood as a book of poetry.73 Varchi’s poem begins with an homage to the ‘new chaste Cypris’ Isabella. The Cypriot in question is naturally Venus, who in most ancient accounts first came to shore on the island following her birth when Saturn’s genitalia fell into the foam of the sea.74 If we look back at the portrait, and reconsider the artist’s obsessive reworking of the positions of the hands to get them precisely correct, we may observe that although he has portrayed Isabella seated, he has clearly given her the gesture of a Classical Venus pudica. 75 In the culture of mid-sixteenth-century Florence, this would have been instantly recognisable. Clothed, and not nude like the ancient statues that inspired the artist, Isabella is indeed a ‘chaste Venus’, appropriate for the young wife who incarnates the goddess of love but does so decorously, within the bounds of marital fidelity. This gesture frames a portion of Isabella’s costume and the body implied beneath it, around her womb. By May 1560, Isabella was pregnant, although she lost the child by September, a month before she and her husband were received by Pius IV to confirm their elevation as Duke and Duchess of Bracciano.76

The witty, literary, Classical reference implicit in the gesture is typical of both Bronzino and Varchi’s poetry. We should expect Varchi to have recognised the intent behind his friend’s concept, and the reference in the sonnet is indeed apt for the painting. Of course, the allusion to Classical sculpture draws the portrait into the ongoing debates over the paragone that Varchi promoted among the artists of the Florentine court. Bronzino was one of the artists he invited directly to reply to his query about the relative merits of painting and sculpture.77 The compositional choice may, however, have been made knowing that it would have been especially appreciated by Orsini, who began collecting antiquities at just this moment, some of which were sent as gifts to the Florentine court.78

If the attribution of the Lady in black to Bronzino and the sitter’s identification as Isabella de’ Medici are accepted this would make it among the last major portraits he executed. Tasked with completing numerous large-scale devotional works, and to design a significant portion of the ephemera for the festivities of 1565 that accompanied the marriage of Cosimo and Eleonora’s son Francesco I de’ Medici to Johanna of Austria, the painter-poet had little time to devote to portraiture subsequently. Into this void would step his students, of whom only Allori rivalled his talents. Allori was particularly favoured as a portrait painter by the women of the Medici court, presumably for his ability to paint luxury textiles and jewels with much of the same dazzling effect as his master. That these depictions were also more idealising may have contributed significantly to his patrons’ satisfaction with his work. Yet, Bronzino’s greater naturalism distinguishes his portraits from those of his students, along with his unrivalled capacity to depict the behaviour of textiles and create a credible, haptic presence for contemporary costumes. The Portrait of a lady in black may now be recognised for who she really is, ‘a portrait of the lady Isabella by the hand of Bronzino’.

14. X-radiograph of Fig.2. (Courtesy Thierry Radelet Laboratory).

dedicated his 1562 anthology Sonetti contro gli Ugonotti to him, in addition to an unpublished manuscript collection of Latin poetry; Furlotti, op. cit. (note 62), pp.6–7; and Gamberini, op. cit. (note 46), p.106, note 300. On Isabella’s erudition, see Furlotti, op. cit. (note 62), p.9; and E. Mori: ‘Isabella de’ Medici e Paolo Giordano Orsini: la calunnia della corte e il pregiudizio degli storici’, in G. Calvi and R. Spinelli, eds: Le donne Medici nel sistema europeo delle corti XVI–XVIII secolo, Florence 2008, II, pp.537–50, at p.550. 73 See Beyer, op. cit. (note 9), pp.176–79, no.41. The appearance of the volume is particularly close to that held by Carlo Rimbotti in his portrait by Salviati; ibid., pp.187–88, no.45. This suggests the likelihood that both painted books were specifically intended to be recognisable as petrarchini. 74 R.E. Bell: Women of Classical Mythology: A Biographical Dictionary, Oxford 1993, p.54; and E. Tripp: The Meridian Handbook of Classical Mythology, New York 1970, p.57. 75 The pose is related to that developed by Bronzino for his Eleonora di Toledo with her son Francesco in the Palazzo Reale in Pisa, although the positioning of the hands more emphatically underlines the connection to the ancient sculptural type in the portrait of Isabella. 76 Isabella’s first pregnancy, documented in March 1559, was similarly unsuccessful, see E. Mori: L’onore perduto di Isabella de’ Medici, Milan 2011, pp.99, 104 and 119–20. 77 For Bronzino’s reply, see ‘Al molto dotto M. Benedetto Varchi mio onorando’, in P. Barocchi, ed.: Pittura e scultura nel Cinquecento, Livorno 1998, pp.66–69. 78 Amendola, op. cit. (note 62), pp.136–37. Isabella herself subsequently commissioned Vincenzo Danti to carve a Venus with two Cupids (Casa Buonarroti, Florence); ibid., 137–39. On Orsini’s collection of antiquities, see B. Furlotti: ‘Collezionare antichità al tempo di Gregorio XIII: il caso di Paolo Giordano Orsini’, in C. Cieri Via, I.D. Rowland and M. Ruffini, eds: Unità e frammenti di modernità: arte e scienza nella Roma di Greogrio XIII Boncompagni (1572–1585), Pisa 2012, pp.197–216.

discoveries in the parma baptismal registers: i

Parmigianino as godfather

The first of three articles presenting discoveries in the Parma baptismal registers relating to artists in the first half of the sixteenth century identifies the occasions on which Parmigianino stood as godfather and explores their significance for understanding his social networks.

by mary vaccaro

Baptismal registers are repositoriesof potentially rich, though often understudied, documentary evidence about artists in early modern Europe. Because the Christian ritual of baptism operates both vertically and horizontally – the sponsor becomes not only a spiritual parent (patrinus or matrina) of the child but also a co-parent (compater or commater) with the child’s parents – the resulting kinship, known as compaternitas, has long offered a fundamental way to forge and solidify alliances among friends, neighbours and business associates. This article is the first of a tripartite series that gleans information from the registers of the Parma Baptistery to map the social networks of Francesco Mazzola, called Parmigianino (1503–40), and other artists active in the city during the first half of the sixteenth century, as well as to elucidate one of his most intriguing portraits.

The present article builds on the discovery of an entry, published in 2007, involving Parmigianino as godfather for the daughter of the painter Michelangelo Anselmi (1491–c.1556), brought to the font in September 1532 (see Appendix 2 below).1 As it turns out, this was neither the first nor the only time that Parmigianino served in such a capacity. Hitherto

This essay and the others in the series are dedicated to the memory of the author’s dear friend and colleague Rick Brettell. 1 See M. Vaccaro: ‘Artists as godfathers: Parmigianino and Correggio in the baptismal registers of Parma’, Renaissance Studies 21 (2007), pp.366–76. 2 For bibliography on baptism and coparenthood in early modern Europe, see Ibid., pp.366–69. Recent studies include G. Alfani: Fathers and Godfathers: Spiritual Kinship in Early-Modern Italy, Burlington VT 2009, transl. C. Calvert; G. Alfani and V. Gourdon, eds: Spiritual Kinship, 1500–1900, London 2012; and G. Alfani, V. Gourdon and I. Robin, eds: Le Parrainage en Europe et en Amérique: Pratiques de longue durée (XVIe–XXIe siècle), Brussels 2015. 3 M. Lopez: Il Battistero di Parma, Parma 1864, pp.116, 137–38, notes 54 and 298. For more on the dogmani, see Ordinarium ecclesiae Parmensis e vetustioribus excerptum reformatum a MCCCCXVII, Parma 1866, pp.71–76. 4 This preface (by Don Francesco Cassola) no longer survives, for which see A. Bianchi: ‘L’archivio del Battistero di Parma’, in G. Zacchè, ed.: Porta Fidei: le registrazioni pretridentine nei battisteri tra Emilia Romagna e Toscana (atti di convegno), Modena 2014, p.161. Yet it was transcribed in its entirety by A. Pezzana: Storia della città di Parma continuata da Angelo Pezzana, Parma 1847, III, appendix, p.13, doc.V; see also the still-extant preface (by Don Gabriele Pelosi, dated 1st January 1487) to the second baptismal register (1487–1504), ibid., appendix, pp.81–82, doc.XIII. 5 No comprehensive analysis of the city’s baptismal registers exists. For a broad overview of the provincial unknown register entries, transcribed and discussed here, reveal that he stood as godfather at least three more times during the last decade of his life for the offspring of fellow artists and architects. Significantly, the documents attest to his ongoing ties to a larger community and challenge the popular narrative told by Giorgio Vasari in the 1568 edition of his Lives of the Artists, in which Parmigianino’s supposed obsession with alchemy distracted him from work and turned him into an unkempt savage.

By the end of the sixteenth century, Tridentine reforms had begun to regulate the sacrament of baptism by limiting the number of godparents to one or, at the most, one of each sex for every child, and obliging parishes to maintain official written records. Earlier case studies of European cities reveal a diversity of regional practices that make generalisations prior to the Council of Trent difficult. Previously, depending on local tradition, babies might have had as many as twenty (or more) godparents. So, too, record-keeping varied widely from place to place and could be desultory or non-existent.2

In 1459, to keep track of familial relations and avoid the possibility of consanguineous marriage, the commune of Parma decided to mandate the registration of its baptisms. It appointed two of its anziani (elders), who

ecclesiastical records, see A. Moroni et al.: I libri parrocchiali della provincia di Parma, Parma 1985, esp. pp.48–50. 6 The first register lacks the years 1462, 1465–68, 1471–75, 1477 and 1482–83 in their entirety, as well as parts of the years 1464, 1470, 1479 and 1481, see Lopez op. cit. (note 3), p.138, note 54. 7 Local usage of one girl’s name (Antea) will be discussed in the final essay of this series. For other applications of data from the baptismal registers, see, for example, G. Hanlon: Death Control in the West 1500–1800: Sex Ratios at Baptism in Italy, France and England, London 2022, esp. pp.62–75, with bibliography. 8 I. Affò: Vita del graziosissimo pittore Francesco Mazzola detto il Parmigianino, Parma 1784, p.12. See also ibid., p.10, note 1, for his incisive rebuttal to a critic lamenting that ‘c’importa pochissimo sapere se il Padre del Parmigianino fosse Filippo o Giacomo; s’egli nascesse alli 11 di Gennajo o ai 13; se questa o quella gli servisse al battesimo di Comare’. 9 E. Scarabelli Zunti: ‘Documenti e memorie di belle arti parmigiane’, Parma, Biblioteca della Soprintendenza ai Beni Artistici e Storici di Parma e Piacenza, MS 102, consisting of ten volumes on which he worked for a halfcentury until his death in 1893. Only the first volume, which spans the years 1050–1450 was published posthumously, see E. Scarabelli Zunti: Documenti e memorie di belle arti parmigiane, ed. S. Lottici, Parma 1911. See also F. Dall’Asta: ‘Indici di “Memorie e documenti di belle arti parmigiana” di Enrico ScarabelliZunti, “coltissimo archivista parmense”’, Aurea Parma 76 (1992), pp.230–47; and Aurea Parma 77 (1993), pp.34–52 and 147–58. 10 L. Testi: ‘Una grande pala di

in turn delegated the task (with compensation) to clerics, presumably the special rank of the Parma clergy known as the dogmani, whose work revolved around the Baptistery in Parma.3 The first baptismal register begins in that year, its preface confirming the decree to log the names of children and their parents, along with the godparents, who were required to be at least twenty-five years of age.4

A careful survey of the earliest registers that collectively span almost a century (1459–1545) gives insight into the pre-Tridentine baptismal customs in Parma.5 The extant records can be fragmentary, especially in the initial volume (1459–86), where entire years are missing.6 Not only does the handwriting change over time – understandably since different scribes undertook the task even during the same period – but so does the basic information provided in the entries. For example, originally only the father tends to be identified as the parent of a given infant. By 1506, however, the mother’s first name also regularly appears, along with her relationship to the father, the most common designation being uxor (wife), yet other labels, such as concubina or amica, suggest that marriage was hardly a requirement. Two or three godparents (at least one of each sex) are typically listed per child, although there are often more, especially for the offspring of eminent families. Indeed, the registers yield fascinating data about socio-historical topics ranging from the frequency of out-of-wedlock births to the relative popularity of names given to babies in Parma.7

Baptismal records also shed light on the everyday lives of artists such as Parmigianino. As early as the eighteenth century the erudite local historian Padre Ireneo Affò pointed to their importance for establishing the painter’s correct birthdate.8 In the next century Enrico Scarabelli Zunti mined the baptismal registers as part of his ambitious compilation of archival documents, laying essential groundwork about artists active in Parma.9 In 1908–10 Laudedeo Testi made genealogical trees for Parmigianino’s earlier extended family as well as for the branch continued by his artist-cousin Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli (c.1505–69), albeit without mention of godparents.10 In 1932 Giovanni Copertini first published the fully transcribed entry for Parmigianino’s baptism, along with a list of his siblings’ birthdays drawn from the registers.11 The entries for these infants have since been published by Marzio Dall’Acqua, who rightly emphasised their value in helping to understand the family’s social status.12

Parmigianino’s father, Filippo (c.1460–1505), and two of his uncles, Pier Ilario and Michele, were painters with impressive connections.13 For example, Ippolito Lalatta – a member of the Consiglio Generale (town council) and an oft-appointed anziano – stood as godfather for Parmigianino and one of his older brothers,14 and the renowned Scipione Dalla Rosa, nephew and universal heir of the powerful canon of Parma Cathedral and apostolic protonotary Bartolomeo Montini, and perhaps best-known today in connection with the artist Correggio, was godfather to two other siblings.15 Fellow artists were also entrusted with the honour:

Girolamo Mazzola, alias Bedoli detto anche Mazzolino’, Bolletino d’Arte 2 (1905), pp.369–85, and idem: ‘Pier Ilario e Michele Mazzola: notizie sulla pittura parmigiana dal 1250 c. alla fine del secolo XV’, Bolletino d’Arte 4 (1910), pp.49–67 and 81–104, esp. pp.89–104. The present author’s survey of the registers has resulted in the addition of two daughters to Pier Ilario’s five known children (Francesca, baptised 14th July 1522; and Antonia, baptised 10th September 1530). Also found was another daughter of Pier Ilario’s son-inlaw Girolamo Mazzola Bedoli (Maria Caterina, baptised 20th December 1530), as well as one of her brothers previously thought to have been born elsewhere (Fabio Camillo, baptised in Parma on 3rd September 1547). 11 G. Copertini: Il Parmigianino, Parma 1932, I, p.49, note 1. 12 See M. Dall’Acqua: ‘I Mazzoli: relazioni sociali di una famiglia di artisti parmigiani’, in L. Fornari Schianchi, ed.: Parmigianino e il manierismo europeo (atti di convegno internazionale di studi), Milan 2002, pp.45–49. Baptismal entries for the children of Pier Ilario and Michele Mazzola have never been published, but perhaps they should: for example, Abbess Giovanna da Piacenza (the patron of Correggio’s so-called Camera di San Paolo, c.1518) was one of five distinguished godparents of Michele’s daughter Giovanna Paola Donella in August 1516. It can hardly be a coincidence that this abbess enlisted Michele to paint in her convent around the same time: for the relevant document of payment, dated 17th November 1519, see C. Prestianni: ‘Un documento inedito sulla committenza di Giovanna da Piacenza nel Monastero di San Paolo’, Aurea Parma 93 (2009), pp.113–32. 13 Filippo had at least ten children, nine of whom appear in the registers between1490 and 1505. For the transcriptions, see M. Dall’Acqua: ‘Parmigianino: i documenti’, in M. Chiusa: Parmigianino, Milan 2001, pp.218–28, at p.218, and idem: ‘Fonti e regesti documentari’, in V. Sgarbi: Parmigianino, Milan 2003, pp.222–29, at p.222. The godparents for one daughter (Maria Caterina, baptised 15th August 1499) are transcribed incorrectly, and belong to a male infant whose baptism follows immediately after hers in the registers: the girl’s godparents were Francesco Zangrandi and Agnese Pisani. 14 Ippolito Lalatta was one of two godfathers to Filippo’s firstborn son, Giovanni Martino (baptised 19th October 1494); this boy’s other godfather (speciales vir dominus Jacopo Baiardi) was even more famous, and part of an elite family that later patronised Parmigianino. See C. Cecchinelli: ‘Badesse, potere, arte e riforma nel Monastero di San Paolo tra quattrocento e cinquecento’, in M. Bola and S. Rossi, eds: Il Monastero di San Paolo a Parma, Parma 2020, pp.205–81, at p.264, note 377. 15 Scipione Montino Dalla Rosa stood as godfather for Filippo’s daughter Ginerva (baptised 28th September 1496) and his son Giovanni Geronimo (baptised 26th May 1498). The same boy’s godmother was Caterina Montini. For Scipione Dalla Rosa and his family, see A. Talignani: ‘La Cappella Montini nella Cattedrale di Parma: un unicum di forme, colori ed epigrafi nella “periferia”’, in G. Periti, ed.: Emilia e Marche nel Rinascimento: l’identità visive della ‘periferia’, Arzano San Paolo 2005, pp.119–79; and Cecchinelli, op. cit. (note 14), esp. pp.227–38, with bibliography.

1. Self-portrait, imposed on preliminary studies for two canephori of the Steccata, by Parmigianino. Pen and brown ink on paper, 10.7 by 7.5 cm. (Chatsworth House, Derbyshire; reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees; Bridgeman Images).

Discoveries in the Parma baptismal registers

one of Filippo’s co-parents was a prominent goldsmith named Giovan Francesco Bonzagni, who later enlisted Parmigianino to return the favour.16 Incidentally, the latter’s aunt Masina was married to Andrea Guidorossi, another goldsmith.17

Although he seems neither to have married nor to have had offspring of his own, Parmigianino was a godfather. Until now, only one case has been discussed, somewhat confusedly, in the literature. It was thought that he brought Anselmi’s son to the font in 1532 and that the boy received the name Francesco in his honour. The two artists did become co-parents that year, but the baptism involved instead one of Anselmi’s daughters, as the discovery of the relevant register entries in 2007 makes clear.18 The son, who was christened as (Antonio) Francesco, with a different godfather (Tommaso Pirolli) in 1530, was more likely the namesake of a grand-uncle who had adopted and instituted the painter as his universal heir.19 Michaelangelo Anselmi fathered a surprisingly large brood of children and built a wide network of co-parents, a matter to be discussed in the next essay of this series. Here, the focus will remain on Parmigianino, who assumed the role of godfather more extensively than has been recognised.

Although christened Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, Parmigianino went by a shortened version of his full name, and contemporary legal documents refer to him as Francesco Mazzola. This name (or a slight variant thereof) appears as the godfather of record nearly a dozen times in the Parma Baptistery registers that span the first three decades of the sixteenth century.20 It is imperative to err on the side of caution when attempting to make a positive identification, however, because of possible homonyms. At least one person in Parma had a similar name, as the entry for a child born posthumously to Francesco Mazzola and his wife Giovanna in 1536 (four years before Parmigianino’s death) demonstrates.21 So, too, the ‘Franciscus de Mazolis’ who is listed as a godfather in 1523 cannot be a match, as the artist had just turned twenty, and godparents in Parma were required to be twenty-five years old or older.22 Parmigianino would have been of age after his return from a brief stint in Rome and Bologna in 1530, but whether he is the same Francesco Mazzola thrice listed in the registers that year unfortunately cannot be ascertained due to lack of information about the other co-parents.23 Still, he can be identified with confidence in no fewer than three new entries that date from 1531 until 1538, as these involve fellow artists and architects.

It is almost certainly he who brought Cesare, the newborn son of Giovan Francesco Bonzagni and his wife, Maria Caterina, to the font in January of 1531 (see Appendix 1). Although details about the other godparents, Giorgio Bosco and Sulpizia Bichi, remain obscure, the father belonged to a family of renowned local goldsmiths. Bonzagni served as an anziano and oversaw the Zecca di Parma (civic mint).24 Two of his older sons, Giovan Giacomo and Giovan Federico, continued to practise the trade, later relocating to Rome to work for Pope Paul III Farnese, as did their nephew, Lorenzo Fragni.25

Moreover, as noted above, Giovan Francesco Bonzagni had already established ties with the Mazzola clan, having stood as godfather for one of Parmigianino’s brothers three decades earlier. That Parmigianino likewise became a co-parent, thereby further reinforcing the bonds of kinship between their families, points to the tight-knit communities among artists and artisans working in Parma.26 Interestingly, the baptismal register refers to ‘magister Franciscus de Mazollis’. The honorific ‘magister’ is found in subsequent entries that can be firmly linked to him, for example, the aforementioned baptism of Anselmi’s daughter in 1532.

A few years later, in 1535, Parmigianino may have served as godfather as many as three times. Although these entries use the honorific magister, nothing is known of the parties involved in the first two baptisms that took place that year, frustrating efforts to identify him positively.27 There can be scant doubt over his participation in the third baptism, however, and the minor variation of his name (‘Giovanni Francesco’) in the relevant entry must be a scribal lapse (see Appendix 3). This is because in this case, the father was one of the painter’s closest friends, Damiano Pieti.

Among the earliest translators and illustrators of Leon Battista Alberti’s learned De Re Aedificatoria, Piete – also an architect himself – was responsible for preparing the setting in S. Maria dei Servi, Parma, for the so-called Madonna of the long neck (c.1534–40; Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence).28 Indeed, the document dated 1534 that is often mistakenly thought to be the contract for the celebrated altarpiece actually concerns Pieti’s architectural modifications to its chapel.29 He was also a steadfast guarantor of his friend’s notoriously protracted fresco project in the nearby church of S. Maria della Steccata during the same years.30

Thus, it comes as no surprise that in September 1535 Parmigianino brought the newly born son of Pieti and his amica Mattea to the font. Little can be said of the godmothers, Rosa Carri and Orsolina Perfetti, but the second godfather was Giovanni Francesco Testa (1506–90), a notable master of wood marquetry and an architect–engineer.31 Five

16 It has gone unremarked that Bonzagni brought Filippo’s son Geronimo Mazzola to the font on 12th Febuary 1501. 17 For the specific documentary references, see Testi 1910, op. cit. (note 10), pp.101–102; and Dall’Acqua, op. cit. (note 12), p.48. David Ekserdjian astutely observed the relevance of this connection to Parmigianino’s drawings for jewellery and metalwork, see D. Ekserdjian: Parmigianino, New Haven and London 2006, pp.253–58. 18 Vaccaro, op. cit. (note 1), pp.371–73, with previous bibliography; see Appendix 2 for a slightly revised transcription. 19 Ibid., p.373 (transcribed). The connection to the avuncular name is here made for the first time. For legal documents regarding Anselmi and his uncle Francesco, see E. Fadda: Michelangelo Anselmi, Turin 2004, pp.58–59. 20 The present author has found eleven entries that list a godfather by this name in the period 1523–38 but will here focus only on those in which the artist can be firmly identified. 21 Archivio della Fabbrica della Cattedrale di Parma, Registri di Battesimo, 1536–45, vol.5, fol.14v. The present author has been unable to identify this father whose daughter (‘posthuma filia Ioannis Francisci de Mazollis et Joanne uxoris’) was baptised on 28th May 1536. The artist had an older brother named Giovanni Geronimo, born in 1498 and still alive in 1517, when the brothers arranged with uncle Pier Ilario for their sister Ginevra’s dowry. Scribes could (and did) confuse names: at least one baptismal entry that surely involves Parmigianino refers to him as ‘Giovanni Francesco’, for which see below. 22 This baptism of ‘Franciscus filius Petri Ioannis de Ferrariis et Lucretie uxoris’ took place on 6th April 1523. On the communal decree of 1459 that set the age limit for godparents, see above. Exceptions could be made, however, as appears to have been the case for Bernardo Bergonzi (to be discussed in the second instalment of this series). 23 The entries record the baptism of children from three different families, respectively, on 29th August and twice on 18th September 1530. A godmother (Lucrezia Baiardi) in one case shares the surname of an elite family linked to the artist, but little more can be said about her or any of the other co-parents. Parmigianino may not be the godfather, given the omission of the honorific magister that appears in entries that are more securely identifiable with him. 24 See entry by G. Pollard in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, XII, Rome 1970, pp.481–82, with previous bibliography. 25 For a useful genealogical tree of the Bonzagni family, without mention of Cesare (who presumably died young), see A. Ronchini: ‘I Bonzagni e Lorenzo da Parma coniatori’, Periodico di numismatica e sfragistica per la storia d’Italia 6 (1874), pp.318–29, esp. p.329. It should be noted, however, that he was still alive and living with his parents and other family members in 1545, the town census of that year listing his age as thirteen; see Archivio di Stato di Parma Comune, busta 1933, ‘Estimo civile, Descrizione degli abitanti di Parma, Vicinanza di Sant’Alessandro’. 26 The registers reveal, for example, that Giovan Francesco Bonzagni took the sculptor Giovan Francesco D’Agrate’s daughter Paola Cornelia to the font on 18th December 1525.