6 minute read

Fuseli and the Modern Woman Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism by kevin salatino

The man who never was – almost

Despite the complications and long delays caused by the pandemic, an impressive number of exhibitions were staged to mark the five-hundredth anniversary of Raphael’s death in 1520. Those in London and Rome were comprehensive in scope, but very different in approach.

Advertisement

by arnold nesselrath

. b. priestley’s play An Inspector Calls, first performed in 1945, has nothing to do with Raphael, except that it is set in 1912 on the evening of 5th April – the day before the anniversary of the artist’s death. The plot concerns a police inspector’s investigation into a young woman’s suicide, with whom each member of the wealthy family he questions was somehow involved; all bear responsibility. After the inspector departs it is revealed that he was a fraud and the case a hoax, at which point the relieved family is told that a young woman has in fact died and a real police inspector is on his way to investigate. As the story begins to repeat itself, facts and fabrications merge.

Raphael is in a way not unlike that young woman. What do we really know about him? No more than two personal letters by him survive, of which only one is autograph. He appears to be a man who never was, and yet his great works in all artistic disciplines – including even archaeological research – are undoubtedly real. That the international celebrations planned to mark the fifth centenary of his death on 6th April 1520 almost never happened because of the pandemic seems symptomatic.

What did the events that were eventually staged reveal about the man or the artist? It should be said at once that it is a great tribute to the international museum community that not only the two main anniversary celebrations, the exhibitions in Rome and London, but also many other smaller shows did nonetheless take place and were enjoyed by large audiences. The hosts of those two major exhibitions responded with great efficiency to the unprecedented impasse created by the pandemic. The exhibition Raffaello 1520–1483 opened at the Scuderie del Quirinale, Rome, on 5th March 2020 but had to close after only three days.1 However, all the lenders agreed to double the periods of their loans, ensuring that

1 M. Faietti and F. Lafranconi, eds: exh. cat. Raffaello 1520–1483, Rome (Scuderie del Quirinale) 2020. The present author contributed an essay to the catalogue. The exhibition was reviewed by Patrizia Cavazzini in this Magazine 162 (2020), pp.983–85, and by the present author in The Art Newspaper (10th August 2020). 2 See, in addition to the exhibitions discussed in this article, M. Deldique: exh. cat. Raphaël à Chantilly: Le maître et ses élèves, Chantilly (Château de Chantilly), 2020; exh. cat. Raphaël à Bayonne: le maître, ses élèves, ses copistes dans les collections du musée Bonnat-Helleu, Bayonne 2020; and A. Cerasuolo et al.: exh. cat. Raffaello a Capodimonte: L’officina dell’artista, Naples (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte) 2021. 3 The July 1984 issue of this Magazine, after it reopened in June the exhibition could continue for longer than planned, to 30th August, although there were restrictions on visitor numbers. The National Gallery, London, reshuffled its entire schedule and postponed The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Raphael for eighteen months, to April 2022. In both cases, the additional collegial and logistic efforts involved cannot be underestimated. All the other institutions staging anniversary exhibitions faced equivalent difficulties in proportion to their projects. The achievements were a worthy tribute to both Raphael’s genius and the attractive personality for which he was renowned.

Despite the difficulties of grasping his contribution, Raphael has enjoyed the status of an icon of Western culture ever since his death five hundred years ago. Consequently, exhibitions were held – or at least planned – for 2020 from St Petersburg to Chantilly and Columbus, Ohio, and from London to Bayonne and Naples.2 Of those discussed in this article, the present reviewer was able to visit only about half, as a result of restrictions on travel caused by the pandemic, although it was possible to get an idea from online films and presentations of some of those that could not be visited, as well as from their catalogues.

The stakes for this anniversary were high, given the enthusiasm across Europe and the United States for the last major Raphael commemoration, the five-hundredth anniversary of his birth in 1983.3 The events of that year opened up new perspectives on his career, providing the impetus for future scholarly developments, such as John Shearman’s monumental catalogue raisonné of all the documents and other sources concerning Raphael up to the year 1602, published in 2003,4 the Vatican’s comprehensive publication of the Acts of the Apostles tapestries woven for the Sistine Chapel and their restoration, which was begun back in 1982,5 and numerous art-historically

dedicated to Raphael, reviewed many of the events and publications of that year. 4 J. Shearman: Raphael in Early Modern Sources (1483–1602), New Haven 2003, which was reviewed by Tom Henry in this Magazine, 148 (2006), pp.696–98. 5 A.M De Strobel, ed.: exh. cat. Leone X e Raffaello in Sistina – Gli arazzi degli Atti degli Apostoli, Vatican (Vatican Museums) 2020. The hanging of Raphael’s tapestries in the Sistine Chapel, as displayed in March 1983, was the subject of a new reconstruction, on display on 14th July 2010, in the light of an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, see C. Browne and M. Evans with A. Nesselrath: exh. cat. Raphael: Cartoons and Tapestries for the Sistine Chapel, London (Victoria and Albert Museum), 2010; this was repeated 17th–23rd February 2020.

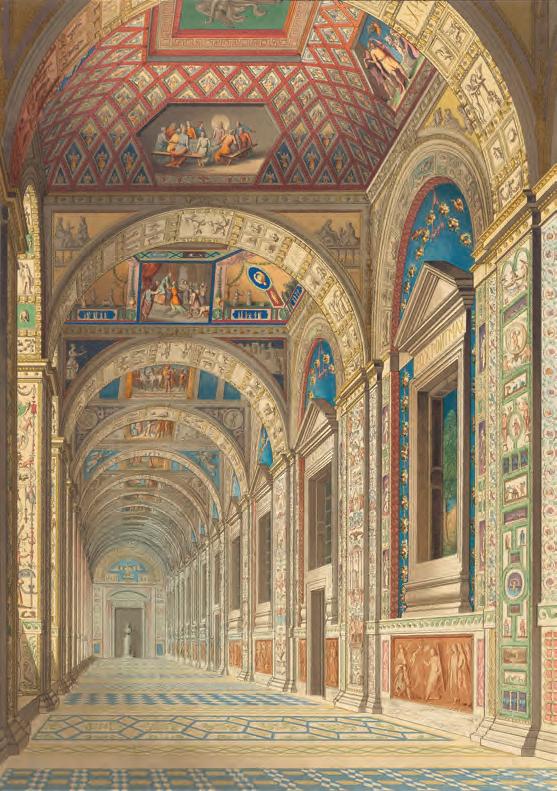

conceived restorations of such works as the Vatican Stanze, the tapestry cartoons in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the Madonna del Baldacchino at Palazzo Pitti, Florence, and Palazzo Alberini, Rome.

All the exhibitions planned for 2020 had to come to terms with the two astounding exhibitions of Raphael’s drawings organised jointly by the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and the Albertina, Vienna, in 2017, as a result of which many sheets were unavailable for lending for reasons of conservation rules.6 There appears to have been no attempt at coordination between those two exhibitions and any of the 2020 projects. As a consequence, the anniversary enterprises remained fragmentary in many of their discourses, since relevant works on specific topics often could not be borrowed, making one very grateful for the rare occasions lenders had allowed exceptions from these rules. Some curators developed an intelligent way of working around this restriction, as in the case of an essential component of the exhibition in Rome, Raphael’s Transfiguration (1516–20; Vatican Museums), the painting said to have been exhibited above the artist’s deathbed in 1520; instead of evoking the occasion through the spectacular auxiliary cartoons for the painting two minor studies and some romantic interpretations of the situation by eighteenth and nineteenthcentury artists were shown.

Exhibitions addressing more regional audiences contributed to forming an idea of the master by choosing topics that illustrated related aspects of Raphael’s universal role. For example, the WinckelmannMuseum, Stendal, one of the smallest contributors to the celebrations, mounted a display of prints from its own collection, Vorbild Raffael – mit Geist und Kenntniß des Alterthums begabet, and even in the absence of a

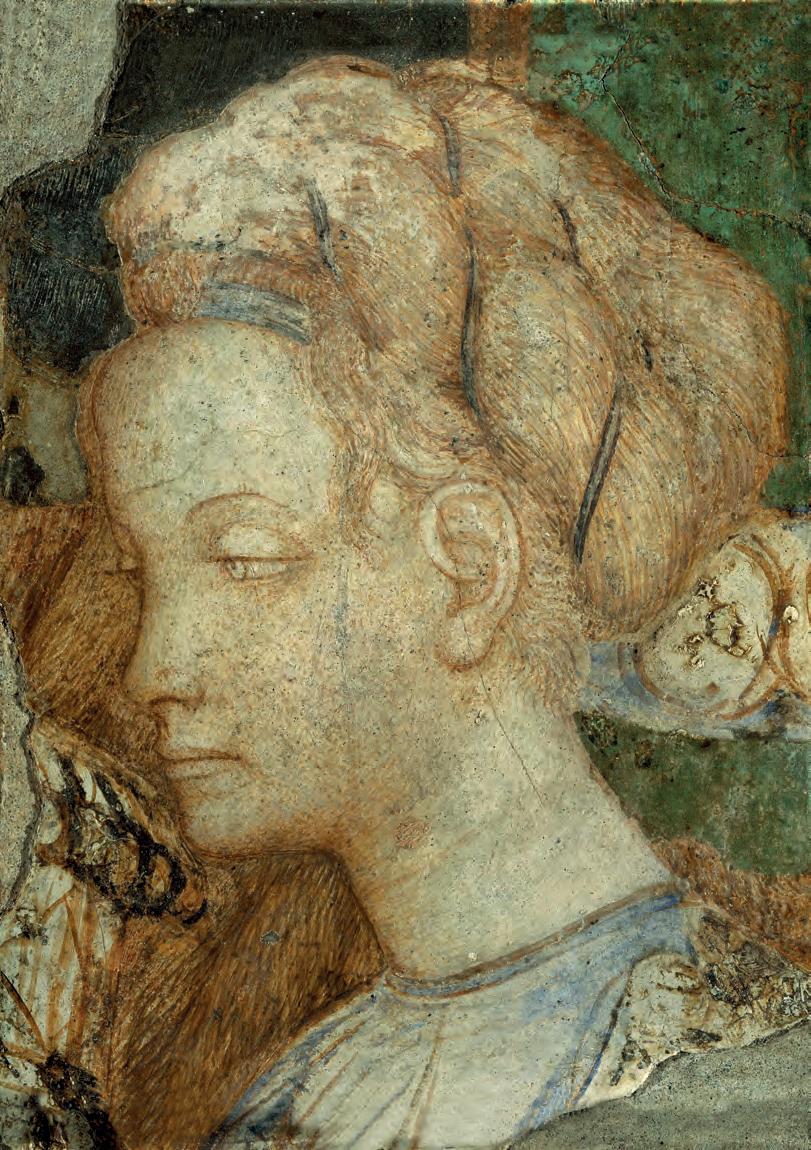

1. The Trinity with Sts Sebastian and Roch and The creation of Eve, by Raphael, photographed after its recent restoration. c.1499. Oil on canvas, each 266 by 94 cm. (Pinacoteca Comunale, Città di Castello).