7 minute read

Pisanello: Il Timulto del Mondo by samuel dawson

Advertisement

The many faces of Mary Magdalene

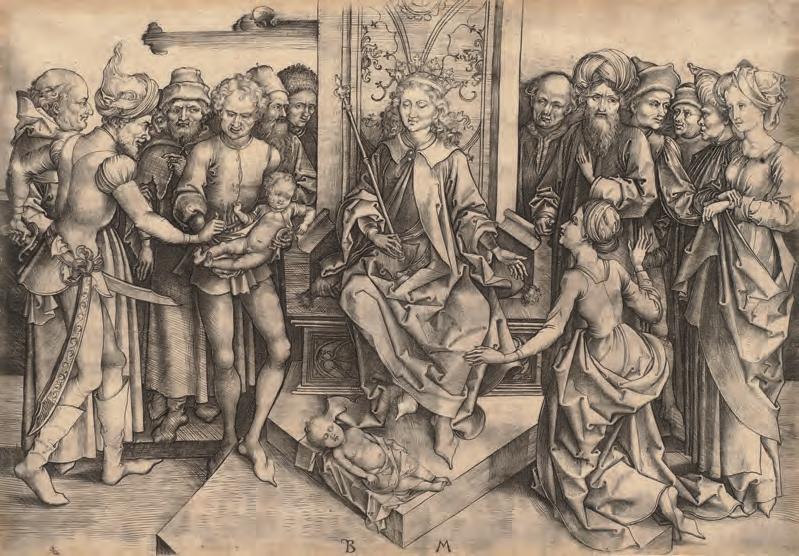

represented, in particular, the gure-types dubbed the ‘maenad under the Cross’ by Edgar Wind – a woman with arms raised in frenzied anguish and profound mourning – and ‘Venus in sackcloth’ by Mario Praz.3 The title of Re ce’s essay, ‘Un lungo preambolo: il medioevo’, is unfortunate; by calling the Middle Ages a ‘preamble’ it belies the importance of medieval art to the subject. It also wrongly implies that the exhibition’s focus is primarily on Renaissance and later art. Nonetheless, the author provides a useful account of the depiction of Mary Magdalene between the third century and the thirteenth. Problems with the identi cation of gures occur here as well. For example, a youthful Christ shown on an early fth-century ivory panel together with the two Marys (Museo delle Arti Decorative, Milan) is described as an angel. Moreover, a nimbed female gure in purple, depicted in the lower register of the Cruci xion miniature from the Rabbula codex (586; Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence Plut. 1.56, fol.13r) is not Mary Magdalene. Although the gure, accompanied by another woman, is depicted meeting the angel at the empty tomb and encountering Christ (Matthew 28:1–8), the same gure – dressed in purple – is also shown standing beneath the Cross with St John in the Cruci xion scene in the upper register. This su ests that the gure represents the Virgin Mary, re ecting a widespread Syriac tradition of identifying her with one of the Marys at the tomb, in a deliberate imposition of her gure on that of Mary Magdalene, especially in the latter’s encounters with Christ.4

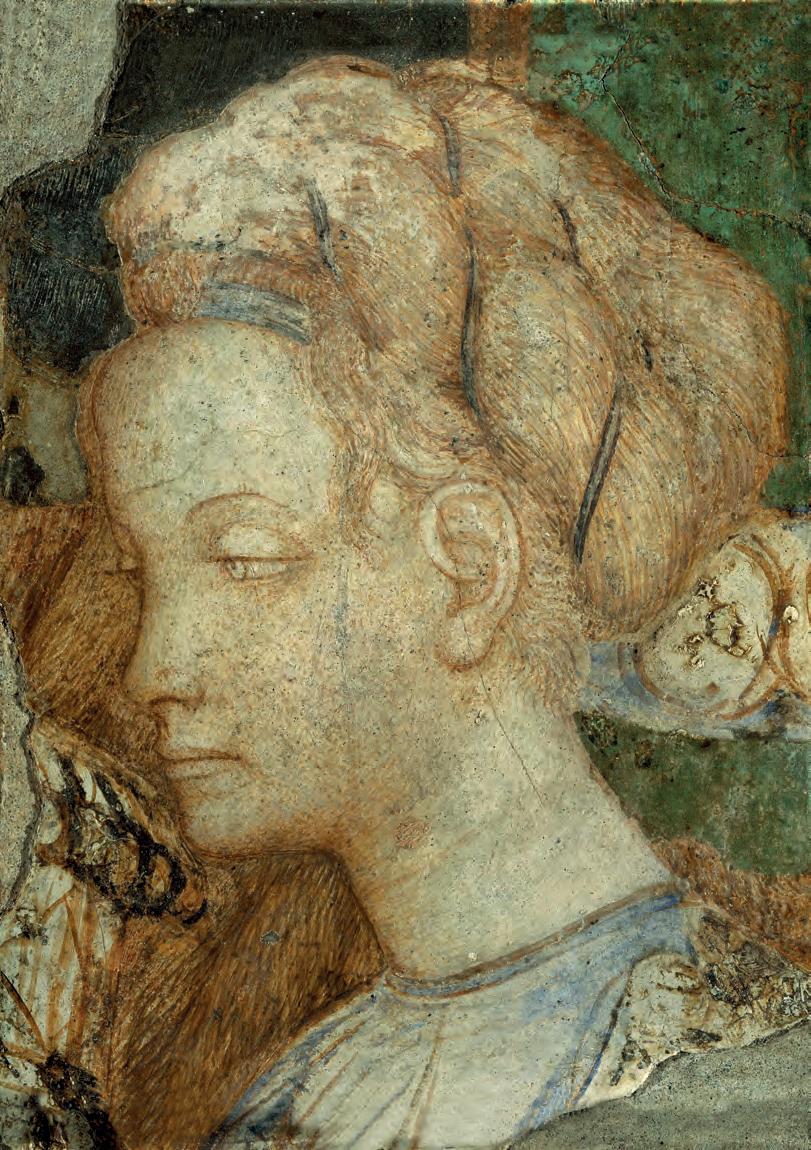

Re ce’s essay ends with a discussion of a panel by the Magdalene Master (Maestro della Maddalena; no.3.10; Fig.2), which includes small images showing scenes from the saint’s Life on either side of a depiction of her as a hair-clad penitential gure. By the time the panel was painted, c.1280–85, Mary Magdalene was the pre-eminent model of repentance for Christians. This image provides the link to the next essay, Secondino Gatta’s account of the later legend of the saint’s missionary activity in Marseilles – which the catalogue refers to as her apostolate – followed by her penitential retreat to a grotto, clad only in her hair and nally her death. Francesco Brasa provides a useful summary of the story of St Mary of Egypt and her con ation with Mary Magdalene’s already complex gure in the ninth century and highlights the fact that the ‘summit of Christian asceticism’ was considered to be the ‘removal of clothes [in a] return to terrestrial paradisal nudity’ (p.60), a phenomenon that was to greatly colour the Magdalene’s image. Alessandro Tomei’s excellent ‘La Maddalena di Giotto’ is an introduction to the rst full fresco cycle dedicated to Mary Magdalene, in the Lower Church at Assisi. He links its commission to the authenti cation of her relics at Saint-Maximin in Provence by Boniface VIII in 1295, to the Golden Legend (compiled before 1298) by Jacobus de Voragine and to Franciscan devotion to the saint as a model of repentance, mysticism and the eremitical life.

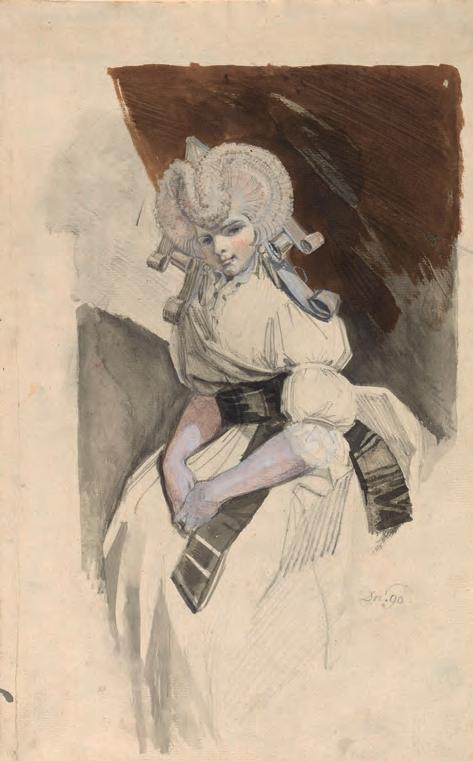

A second essay by Re ce o ers an introduction to the variegated gure of Mary Magdalene in the fteenth century. She considers the saint in her role as a patron of confraternities and congregations, her fundamental role in sacre rappresentazioni, which gave rise to sculpted life-size Lamentation groups, discussed in an essay by Virna Ravaglia, and the fashion for women to be depicted as Mary Magdalene, such as Catherine of Brabant, apparently portrayed as the saint in Rogier

3 E. Wind: ‘The maenad under the Cross I: comments on an observation by Reynolds’, Journal of the Warburg Institute 1 (1937), pp.70–71; and M. Praz: Secentismo e marinismo in Inghilterra: John Donne-Richard Crashaw, Florence 1925, cited in H.J.C. Grierson: Cross-Currents in English Literature of the XVIIth Century, London 1948, p.181. See also M.M. Malvern: Venus in Sackcloth: The Magdalen’s Origins and Metamorphoses, Carbondale IL, 1975. 4 See J. Leroy: Les manuscrits syriaques à peintures conservés 2. St Mary Magdalene with eight scenes from her life, by the Magdalene Master. 14th century. Tempera on panel, 164 by 76 cm. (Galleria dell’Accademia & Museo degli Strumenti Musicali, Florence; Bridgeman Images).

dans les bibliothèques d’Europe et d’Orient: contribution à l’étude de l’iconographie des églises de langue syriaque, Paris 1964, pp.151–52; and M.R. James: The Apocryphal New Testament, Oxford 1920, p.88. See also R. Murray: Symbols of Church and Kingdom: A Study in Early Syriac Tradition, Cambridge 1975, pp.329–35. 5 A. Warburg: ‘Delle “Imprese amorose” nelle più antiche incisioni fi orentine’, in idem: The Renewal of Pagan Antiquity: Contributions to the Cultural History of the European Renaissance, transl. D. Britt, Los Angeles 1999, pp.169–83, at p.174.

The many faces of Mary Magdalene

van der Weyden’s Braque polyptych (c.1452; Musée du Louvre, Paris). Donatello’s wooden sculpture of the penitent Magdalene (c.1450; Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence), which was not in the exhibition, is the progenitrix of the equally hirsute and ha ard representations of the saint that followed it, in Antonio Pollaiuolo’s fresco of a beautiful elderly woman, carried to heaven by angels (c.1455–60; Museo della Pala del Pollaiolo, Sta ia Senese; no.5.5) and sculptures by Bu iano (c.1440; S. Maria Maddalena, Pescia; no.5.1), Don Romualdo da Candeli (1455; Museo della Collegiata di S. Andrea, Empoli; no.5.3), Francesco da Sangallo (1519; Museo Diocesano di Santo Stefano al Ponte, Florence; no.5.8) and Andrea della Robbia (c.1495–1505; S. Jacopo, Borgo a Mozzano; no.5.9).

In the exhibition these sculptures functioned as sentinels anking a long corridor outside the former convent cells, in which some of the most beautiful images of Mary Magdalene on show were exhibited. Among them were Masaccio’s aming, anguished, v-shaped gure below the Cruci xion (no.5.13; Fig.1) and the cleverly paired pietàs by Giovanni Bellini (1472–74; Musei Vaticani, Rome; no.5.16) and Marco Palmezzano (c.1500; Museo Civico di Palazzo Chiericati, Vicenza; no.5.17), moving depictions of Mary Magdalene as mourner and caritative myrrhophore, bent over the dead Christ’s wounds, her ointment jar held in the hand of Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea. These depictions are ably analysed by Acidini in her essay ‘Nel cinquecento, tra classicismo e inquietudine’, in which she also discusses representations of the ‘heroine of the gospels’ (p.97) by, among others, Luca Signorelli and Raphael; she includes an excellent study of the Noli me tangere in paintings by Fra Angelico, Titian, Corre io and, above all, Federico Barocci (1590; Gallerie degli U zi, Florence; no.6.26), with its wondrous ‘dialogue of glance and gesture’ (p.103).

Acidini emphasises that the posture of the standing Magdalene in Jacopo Pontormo’s Noli me tangere (no.6.23; Fig.4) was, as Federico Giannini explains in the entry on the painting, based on a lost cartoon by Michelangelo for a painting that had been commissioned on behalf of Vittoria Colonna, which Pontormo executed under Michelangelo’s supervision. It seems that both Michelangelo and Pontormo were unaware of a similar, slightly earlier interpretation of the scene by Hans Holbein (1526–28; Royal Collection). Mary Magdalene’s garb, however, is not ‘modern’, as Acidini claims (p.104), but a type of ctive all’antica garment, one that Aby Warburg described as a ‘sprightly ideal costume, all’antica [. . .] or of those dancing maenads, consciously imitated from the antique’.5 Despite what Acidini writes, there is also no evidence that Colonna was in uenced by the treatises of the humanist Jacques Lefèvre, De Maria Magdalena (1518) and De tribus et unica Magdalena disceptatio secunda (1519), in which he aimed to isolate the di erent facets of the tripartite identity of the saint. Although in her writings Colonna celebrated Mary Magdalene as an ‘apostola’, she regarded her, above all, as a repentant sinner and model for

3. Mary Magdalene from the sculptural group Lamentation, by Guido Mazzoni. c.1483–85. Polychrome terracotta. (Chiesa del Gesù, Ferrara; photograph Nicholas Pickwoad). 4. Noli me tangere, attributed to Jacopo Pontormo. c.1532. Oil on canvas, 175 by 133 cm. (Casa Buonarroti, Florence; Bridgeman Images).