Anne van Casteren

Medicine and art Clean as a whistle, smelling like a rose Ah, the luxury of a good bath. Those who have ever lived in a classically mold-ridden student house, complete with a temperamental broken shower, will know this seemingly unattainable daydream of a clean, bubbly, warm tub of water. And while you may hopelessly look forward to visiting that one friend’s or parent’s bathroom, to an ancient egyptian your collection of soaps and options of hot or cold water would be luxury enough. With the help of two mosaics, we will explore some of history’s highlights when it comes to keeping clean.

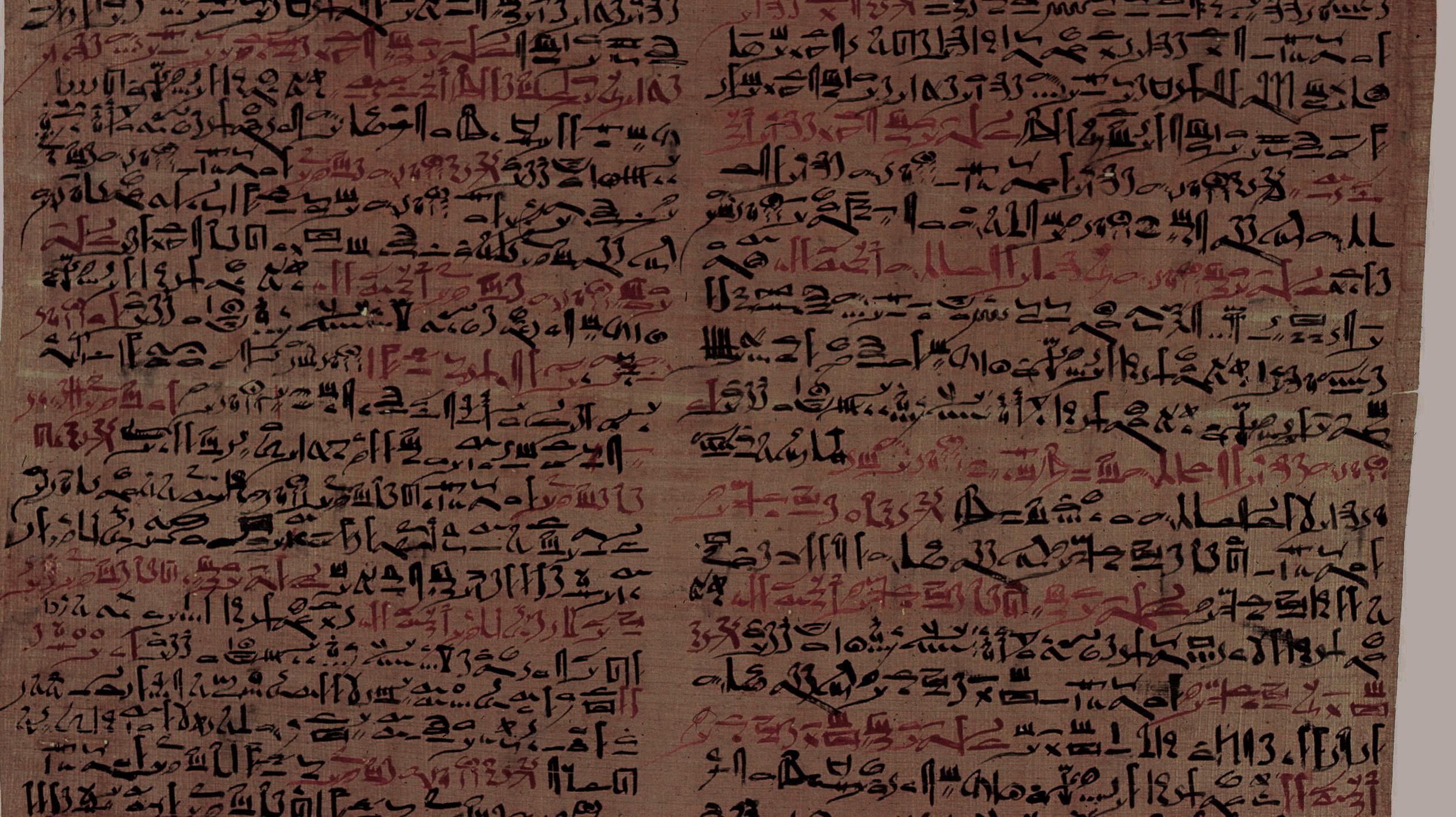

The basic recipe for a non-modern soap is as follows; animal fat or oil is combined with alkaline salts (such as sodium carbonate out of ashes), and sometimes a form of exfoliant. In its most basic form, this results in a harsh soap that is suitable for washing cloth or hair. Cleaning ones body and surroundings is a necessary habit almost all animals have, which has medical relevance because of its goal of removing disease causing factors (such as bacteria). While keeping clothing clean probably decreases the chance of contracting some diseases, it is not a direct medical intervention and therefore not of any interest to us. The real mystery is the use of body soap. Personal hygiene habits using soap have a direct influence on occurrence of skin disease and infection. It removes bacteria and grime from the skin, and prevents or soothes skin conditions such as eczema. A softer soap is needed for this purpose, which ideally also has disinfecting properties. Without knowledge of bacteria or other causes of disease, how could a progressing society come to the conclusion to use soap for medical reasons? Baffling as it might be, soap has been used almost since the start of recorded history. A fascinating document thought to be written around the 1550 century BC, called the Ebers papyrus, describes various treatments for common diseases. It also features some surprisingly accurate interpretations of anatomy, but we’ll ignore those for now. A chapter on skin disease features multiple options of ointments and, as one of the earliest sources, a recipe for soap. The Ebers papyrus was written in possibly the most wealthy period of egyptian ancient civilization, which explains the complex medical knowledge featured.

22

Many recipes in the skin disease chapter use honey, onion, sea salt, milk or urine. These ingredients have been shown to have anti-inflammatory or disinfecting purposes. Their use of mild and moisturizing fats and oils along with the “active’’ ingredients is now also known to soothe eczema. Combined with a strong belief in the gods that blessed and recommended these treatments, it is not difficult to imagine that an ancient egyptian would experience a soothing or even curing effect on mild skin conditions. Even wounds on the skin would benefit from a more conscious and possibly anti-inflammatory wash. A fragment of the Ebers papyrus can be seen behind the article headline. In contrast to their southern counterparts, the Romans didn’t seem so keen on body soap. Early accounts only show the existence of harsh fabric soaps that are too drying for use on the skin. The idea of soap being used for medical reasons seems at this point to not have survived the Egyptian era. Most are familiar with the roman bathhouse, where warm and cold baths were available. For sports, oil was used on the skin that was removed not with soap, but with a scraping stick. While bathing, public or private, was common, the use of soaps was not. At least not until a milder variant was discovered that could be used frequently on the skin. In the mosaic shown at the bottom of the next page, which is made in the classic style found in Roman bath houses, a goddess can be seen preparing herself to get dressed. The way she holds her hair suggests she has been washing up.