Hidde Kleijer

Chronic pain Why we need a different philosophy of mind in medicine AAAAAAAAAAA! A man in obvious and unrelenting pain arrives at the emergency department (ED); a large nail sticking through his shoe from the sole to the top. Horrendously, no pain medication reduces his pain. Weirder still, when they remove his shoe there’s no damage to his foot: the nail has gone right between his toes. Still, his pain is very real, what’s going on here? This quirky and altogether interesting case was reported on in the British Medical Journal in 1995. Dualism’s counterpart, monism (or physicalism), does away with the concept of an immaterial substance. It entails all phenomena of the mind (like pain) can be directly reduced to physical processes. This reductionist view struggles to account for these phenomena, however. So a middle ground, albeit still a form of physicalism, emerged: functionalism. In essence, the same way the kidneys function to produce urine, the mind is a (very complex) function of the nervous system in a way that is analogous with a computer: the nervous system is the hardware, the mind is the software (mindware). However, this analogy is not perfect.

As a former philosophy student and Panessay editor, cases like this excite me wildly. Having worked as a doctor for 4 years now (ED, neurology, pain care, and psychiatry), I have kept a keen interest in everything bordering neurology and psychiatry. I’d love to share some of the insights -I think to- have gained and please bear with me during two paragraphs of philosophy.

“Essentially, mind and body are two sides of the same coin.” I wholeheartedly believe our philosophical views on matters like the mind relate strongly to how we work in medicine. In fact, the philosophy of dualism is reflected in our strict division between somatic disciplines (like neurology) and psychiatry. Unsurprisingly then, dualism entails that there is a strict division between two matters: the material (the body) and the immaterial (the soul). Most philosophers nowadays think that this view is problematic. Its biggest flaw can be summarized by one question: How could these mutually exclusive matters interact?

22

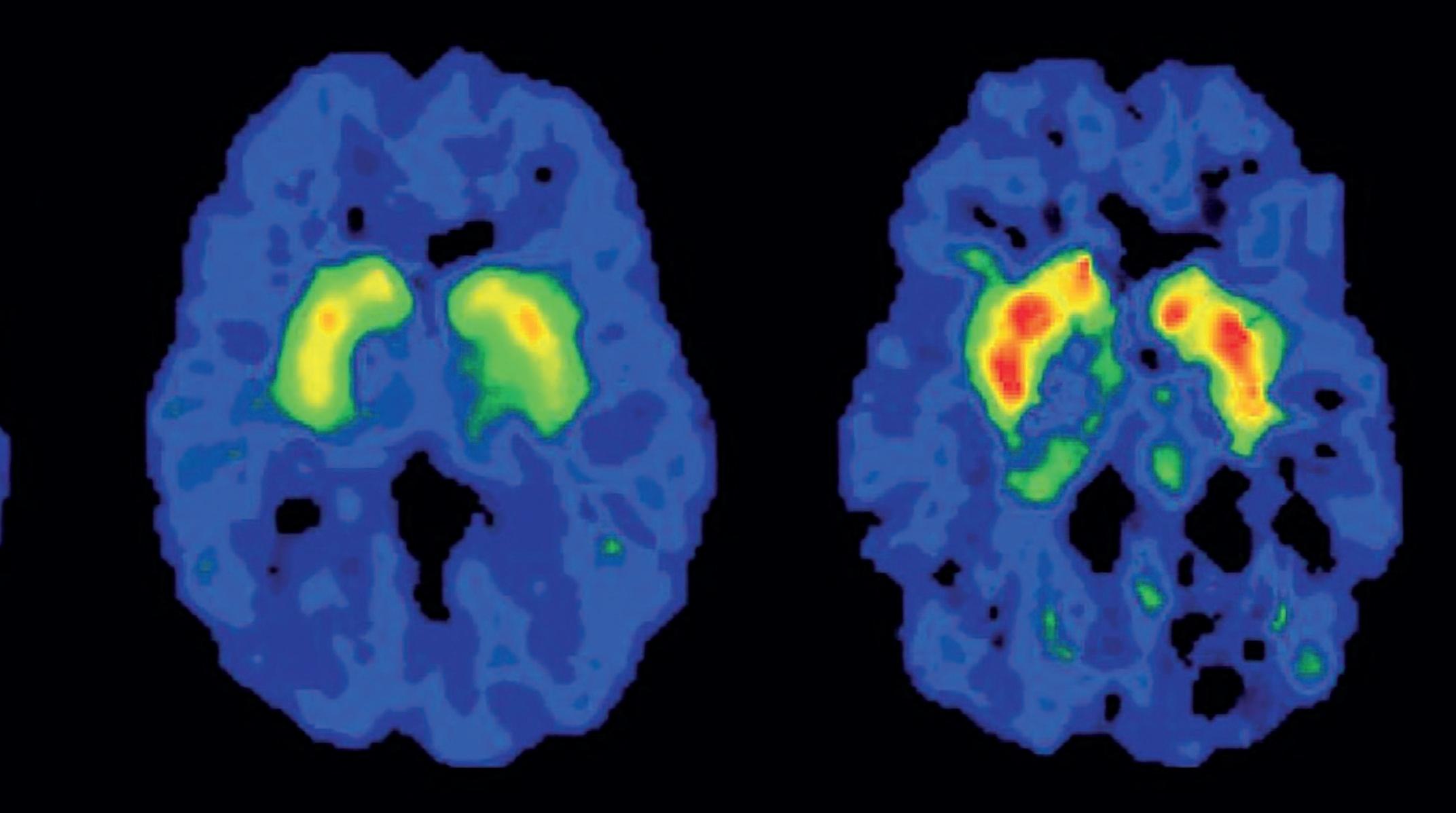

Mindware is directly related to the way the nervous system is organized. Essentially, mind and body are two sides of the same coin. To me, the case above clearly demonstrates why we need a functional perspective on the mind to be able to explain the pain that the formerly mentioned patient was in. For if it was purely a matter of pain of the soul, how could a physical event like a nail puncturing a shoe give rise to that? And if it was purely a matter of the body, how could there be pain without any damage to it? Interestingly, we are learning that something in the function of the pain system can go awry, especially in chronic pain syndromes. Our pain system isn’t that different from a fire-alarm: a noxious stimulus signaling potential damage to the body (i.e. smoke) gets picked up by a nociceptor (the smoke sensor), is transmitted via neurons to the central nervous system where this signal is ultimately processed by the brain and the “alarm” goes off: pain! Such a system can become too sensitive or indiscriminate, giving rise to many false alarms; fire alarms in student kitchens anyone? When this happens in the pain system, pain can arise with a small, or even no stimulus. This is called central sensitization pain: