SKYLAR VENTERS

WINTER 2023

SKYLAR VENTERS

WINTER 2023

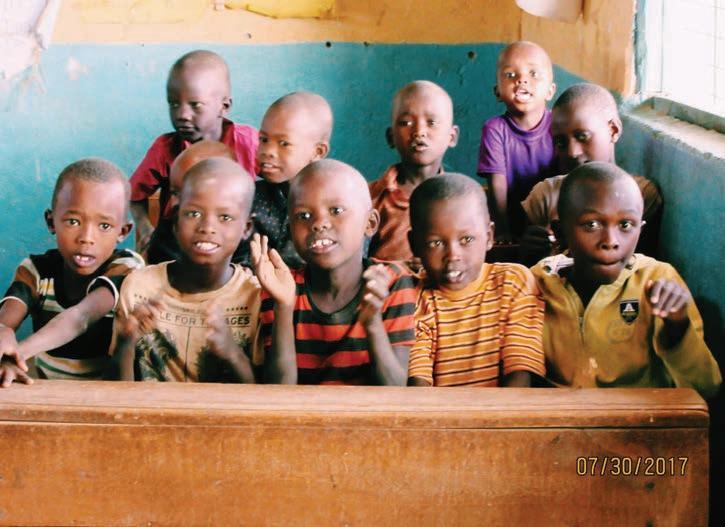

When I was sixteen, I was able to travel outside of the country for the first time. I spent two weeks in Kenya, meeting new people, and immersing myself in the culture. From driving past Africa’s largest slum Kibera, to spending the night in a hut made of dung at a local Masai village, I began to feel truly humbled. I visited a women’s village called Umoja where I learned about the archaic practices of female genital mutilation that still take place today. I listened to the stories of people not far from my age, and began to realize the immense privilege I had been born with. From then on, I knew I wanted to spend my life doing my best to enact change. Throughout my education at SCAD, I have come to realize the impact that can be made through design. The relationship between ourselves and the physical environment we are in is absolutely intrinsic. I believe we can change the world through design, and I think education is at the root of it all.

Debt, marginalization, energy poverty, and climate vulnerability are just some of the challenges facing developing countries in today’s times. Education is a crucial aspect of improving the quality of life that exists in these developing countries. Economic vitality is driven by the increase in future job placement caused by adept schooling. Self-sufficiency in educational infrastructure will help to protect nations, such as Kenya, from climate vulnerability and related issues.

The scope of the project includes the renovation of an upper level schools established by The Braeburn Group of International Schools. Utilizing a holistic approach that celebrates the existing culture and vernacular, the project will comprise of a preparatory school based in Nairobi, Kenya. The interiors of the school will be designed to enhance the success of students post-graduation to help them become productive citizens, and to ensure a happy and sustained livelihood after schooling. Primary users will include students, ages 14-18, in addition to teachers, faculty, and supporting members of the community. While maintaining the pragmatic standards of all Braeburn Schools, the design will take into consideration the following existing issues in educational interiors: Community Involvement, Classroom Confinement, Acoustical Interference, and Social & Emotional Wellbeing. With the community and environment at the forefront of the design process, Nairobi’s Newest Campus was created.

Debt, marginalization, energy poverty, and climate vulnerabilit y are just some of the challenges facing developing countries in today’s t imes. Education is a crucial aspect of improving the quality of life that exist s in these developing countries. Economic vitality is driven by the increase in f uture job placement caused by adept schooling. Self-sufficiency in educational infrastructure will help to protect nations, such as Kenya, from climate vulne rability and related issues.

The Braeburn Group of International Schools is funding the reno vation of one of their upper level schools. Utilizing a holistic approach that celebrates the existing culture and vernacular, the project will comprise of a preparatory school based in Nairobi, Kenya. The interiors of the school will be designed to enhance the success of students post-graduation to help them be come productive citizens, and to ensure a happy and sustained livelihood a fter schooling. Primary users will include students, ages 14-18, in addition to teachers, faculty, and supporting members of the community. While maintaining the pragmatic standards of all Braeburn Schools, the design will take into co nsideration the following existing issues in educational interiors: Community I nvolvement, Classroom Confinement, Acoustical Interference, and Social & Em otional Wellbeing.

Utilize a holistic design approach in order to integrate and celebrate existing culture, traditions, and community.

Create interiors that help prepare students for higher education and/ or a career in their chosen field.

Drive up the proximate economic vitality by increasing future job placement and general skill set in multiple trades and professions through innovations in design.

Implement furniture, fixtures, and equipment from, or inspired by, the surrounding vernacular and culture.

Feature spaces that utilize collaboration to target the promotion of social and mental well-being.

Improve the self-sufficiency of the facility in order to further enhance student and faculty independence and skill sets.

Leiringer, R., & Cardellino, P. “Schools for the twenty-first century: school design and educational transformation.” British Educational Research Journal 37, no .6 (2011): 915–934. Accessed October 1st, 2022. http:// www.jstor.org/stable/23077016

Conducted by The Building Schools for the Future Programme, this study analyzes four Scandinavian case studies regarding schools designed or redesigned for reform in education. Hellerup Skole is a Copenhagen based education building that utilizes the design of the built environment to allow students to feel in control of their learning and activities in order to create the perception of a secure environment. This is done by allowing centralized functions to occur in the atrium/staircase, while leaving the concentrated learning areas to occur in the “home areas” and “tutor rooms.” Heimdalsgades Overbygningsskole is a bread and paper factory that has been converted into a school. Instead of featuring a traditional classroom setting, there are five zones designated for a separate curriculum: The Studio, The Workshop, The Station, The Laboratory, and the 10th grade environment. Each zone is outfitted with specific equipment and furniture pertaining to the function of the room, but all environments are flexible in their arrangement and overall design. Students are assigned a schedule and curriculum, but are given the freedom to choose where they want to work within the school, and are encourage to establish their own individual space.

Moubarak, L & Qassem, E. “Creative eco crafts and sustainability of interior design: Schools in Aswan, Egypt as a case study.”

The Design Journal 2, no. 6, (2018): 835-854, Accessed October 1st, 2022. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/14606925.2018.1533717

DOI: 10.1080/14606925.2018.1533717

Due to the unprecedented rise in mass production of materials and products, many craftsmen lack the economic incentive to continue the pursuit of their craft. This leads to a rise in market exclusion for many local and traditional trades. Based on schools in Aswan, Egypt, this study discusses the positive social, economic, and environmental impact of specifying Eco and heritage crafts in place of contemporary materials and finishings. On a social level, specification of these crafts can help to establish a sense of place within the built environment that promotes the representation of a cultural identity, as opposed to mass assimilation into the existing world. At the economic level, support of local tradesmen drives vitality within the surrounding community by promoting job increase in marginalized trade groups. Doing so also reduces transportation costs of goods and services, and minimizes the expense process of disposing of waste. Environmentally, specifying Eco and heritage crafts aids in the reduction of waste and pollution caused by artificial materials and finishings. In addition, creative Eco crafts employ passive ventilation methods which can replace energy intensive mechanical ventilation systems.

McGee B, & Park, N. “Colour, Light, Materiality: Biophilic Interior Design Presence in Research and Practice.” Interiority 5, no. 1, (2022): 27-52, Accessed October 1st, 2022.

https://doi.org/10.7454/in.v5i1.189

DOI: 10..7454/in.v5i1.89

This article discusses the biophilic design hypothesis that details how nature-based environmental design promotes human health and well-being. The study was based on the application of the Biophilic Interior Design Matrix (BID-M) which was created in order to support the application of biophilic design on interiors, and its consequent effects. As a result of the study’s literature review and design practitioner perceptions, evidence was found that supports the conclusion that a holistic approach to interior design includes nature based application of color, light, and materiality. The BID-M model is based on six categories: actual natural materials, natural representations, natural patterns and processes, color and light, place-based relationships, and human nature relationships. These categories are further broken down into a total of 54 attributes that further asses the application of biophilia. Results concluded that color can influence behavior and cognition of users, such as in the instance of wayfinding. There was a significant correlation between access to natural light and the improvement of task performance as well as energy savings. Overall, it is stated that”environments perceived low in creativity potential were consistently windowless, finished in manufactured or composite materials, and with overall cool colors.

Donkin, R. & Kyn, M. “Does the learning space matter? An evaluation of active learning in a purpose-built technology-rich collaboration studio.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 31, no. 1, (2021): 133-146, Accessed October 1st, 2022. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5872

There is mixed evidence in the topic of whether or not technology-rich learning environments promote positive outcomes compared to the traditional pedagogic classrooms, or whether this use of technology is ultimately just a distraction. This is not the case when it comes to team-based learning facilities that are enriched the implementation of technology. The report examines a study in which quantitative results show 11.8% improvement in test scores for students who studied curriculum in a collaborative environment as opposed to a standard learning environment. Results also show the positive impact of exam results caused by a technology-enable collaboration studio. In addition to test result improvement, the study found that a technology-rich collaborative space can also increase implicit outcomes of communication, motivation, and professionalism.

Kirschner, M.; Golsteijn, R.H.J.; Sijben, S.M.; Singh, A.S.; Savelberg, H.H.C.M.; de Groot, R.H.M. “A Qualitative Study of the Feasibility and Acceptability of Implementing ‘Sit-ToStand’ Desks in Vocational Education and Training. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 849. (2021) Accessed October 1st, 2022. https:// doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030849

In a traditional school setting, the majority of student time is spent in a sedentary position. This is counter-intuitive to studies that show how the interruption of a human’s sedentary behavior is directly correlated with the improvement of cognitive functioning, physical health, and mental well-being. Despite this evidence, research also indicates that roughly 80% vocational education and training students employ a sedentary lifestyle. Utilizing semi-structured focus group interviews, this study aimed to analyze the implementation of sit-to-stand desks as a means of interrupting sedentary positions, and therefore, positively impacting health and behavior. The experiment which analyzed the subjective matter of 33 students, indicated positive attitudes towards the implementation of these desks, but that the teachers played a crucial role in the implementation of them. The study found that students would not utilize the desks, independently, but relied on the structure motivation of the teachers in order to fully reap the cognitive, physical, and mental benefits of the sit-to-stand-desks.

Frelin, A. & Grannäs, J. “Designing and Building Robust Innovative Learning Environments.” Buildings 11, 345, (2021), Accessed October 1st, 2022. https://doi. org/10.3390/buildings11080345

This study examines two different spatial designs of schools and the behavioral results of how these environments promote innovative learning methods and practices. There was an underlying focus placed on the differentiation of process and phases it took to develop these two school models. The data accumulated was made up of site visits, project briefs, and direct interviews with stakeholders. This data was analyzed using a model that emphasized the education vision, organization and approach, and physical environment. Results showed four common themes: Continuity, Preparation, Alignment, and Participation. Both school design processes revealed participation of several stakeholders at all phases demonstrated continuity in the overall design process. In both studies preparatory processes including site studies, research, and on-site workshops were a crucial aspect of the design process.

Bruni, E.; Dall’O, G.; Panza, A. “Improvement of the Sustainability of Existing School Buildings According to the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)® Protocol: A Case Study in Italy” Energies 6, no. 12, (2013): 6487-6507, Accessed October 1st, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/en6126487

Because the majority of an adolescent’s time is spent at their respective center of education, it is crucial that the design of this building prioritize the health and comfort of its users at all levels of design. This study outlines the sustainable improvement of fourteen school buildings located in Northern Italy, and how their redesigns meet the standards and requirements of LEED® certification. These examinations highlight the cost effectiveness of improving existing structures to meet LEED® standards, and whether the benefits fiscally outweigh these costs. Results found that investments in energy efficiency had the ability to generate income as a result of the saving of conventional energy sources. There were questions in whether energy efficiency should be the end-all-be-all for sustainable improvement of the buildings’ redesigns, but ultimately results of the study showed that a comprehensive approach in the building’s overall sustainability caused net economic assets to emerge.

The Braeburn Group of International Schools are internationally derived co-educational facilities that teach students British/I nternational curriculum. They have locations throughout Kenya and Tan zania. Braeburn was founded in 1979 on Gitanga Road in Kenya, and had just seventy students and twenty teachers. From there it grew t o 10 schools and is now educating over 4,000 students. Their brand c olors are different hues of blue, accented by white. Their educationa l values are based on building confident individuals, responsible citize ns, and learners who enjoy success after schooling.

“Students join our primary and secondary schools with a large range of previous educational experiences and often with limited or no English. Through personalized learning, we aim to meet each child’s individual needs and transition from different systems or curriculum is very successful.”

“The triangle of teachers, parents, and children is strengthened by open communication. We actively encourage comments and suggestions from parents and pupils; our Headteachers operate an open-door policy.”

“We help our children discover the fulfillment that comes through learning, in a fun and caring environment. Our teachers inspire students to be confident individuals, responsible global citizens, and successful life-long learners.”

The project functions to serve as an educational institution for students. The primary users of the space are students, ages 14-18 in academic years 9-12. This student body will be made up of both local and international students, from across the globe.

Studies show that based on student performance, a school of 600-900 students is ideal for secondary education. Classrooms are designed to best accommodate 18 pupils.

The education facility is also be used professors, faculty, educational professionals, and staff. These users will service the primary users through the utilization of the facility.

Tertiary user groups might include parents or guardians of the students and volunteer community members who will impact function and operations in various ways.

AGE: 17

GENDER: FEMALE

ETHNICITY: KIKUYU

NATIONALITY: KENYA

Mary Kimani was born in Nairobi, and is the oldest of two. Her dad is doctor, and her mom is a communications liaison. Both her parents are active members of the school community. Mary is going into her final year of prep school and has plans to pursue higher education after graduation. Eventually she wants to follow in the footsteps of her father and practice medicine.

Mary is a determined student who is prideful of her academic accomplishments. She enrolled at this institution to help improve her collaborative skills, and to increase her likelihood of college acceptance.

AGE: 14

GENDER: MALE

ETHNICITY: LUHYA

NATIONALITY: KENYA

Paul Mwangi comes from a family of farmers. He was born and raised in Nyathuna, Kenya, a rural farming town, just outside of Nairobi. Paul has five younger siblings, and a lot of responsibilities. His parents enrolled him in prep school in order to further his chances of getting a job in manufacturing.

Paul has struggled in the past with schooling, and relies on a one-on-one education style. Paul is used to being physically active, and has trouble remaining still for long periods of time. Paul is great at collaborating on projects, and participating in team building exercises.

AGE: 16

GENDER: MALE

ETHNICITY: WELSH

NATIONALITY: UK

Carter Abbott was born and raised in the United Kingdom. He is an only child, and both of his moms work in finance. Carter enrolled at this institution because he has a passion for philanthropy and wants to pursue a career in infrastructure development.

Carter is primarily an auditory learner, and relies on a lecture heavy class setting. He is looking to build connections that can take with him into his career. He wants to network locally, and immerse himself in the surrounding culture.

PROFESSOR VOLUNTEER

AGE: 45

GENDER: FEMALE

ETHNICITY: LUO

NATIONALITY: KENYA

Amina Mutua was born in Nanyuki. She and her family moved to Nairobi when she was nine, because of a job opportunity her father had received. In addition to foundational courses, Amina teaches a class in production management. Before becoming a teacher, Amina worked in fertilizer manufacturing for 10 years.

Amina believes in having an adaptable teaching style to meat the needs of her diverse student groups. She strives to facilitate a collaborative, productive, and inclusive classroom environment.

AGE: 37

GENDER: MALE

ETHNICITY: KAMBA

NATIONALITY: KENYA

Peter Onyango is a wildlife ecologist from Nakuru. He moved to Nairobi in his late twenty’s to pursue a job opportunity. He has a background as a park ranger and wildlife photographer. Peter is very prideful of his background and has a passion for giving back to his community.

Peter’s role at the institution as a volunteer member of the community is to educate students on real world experience in his field. Peter conducts weekly seminars in order to inform students on local and global ecological issues.

KEY

Grid Organization

Radial Organization

Secondary Circulation

Primary Circulation

Approach/Departure

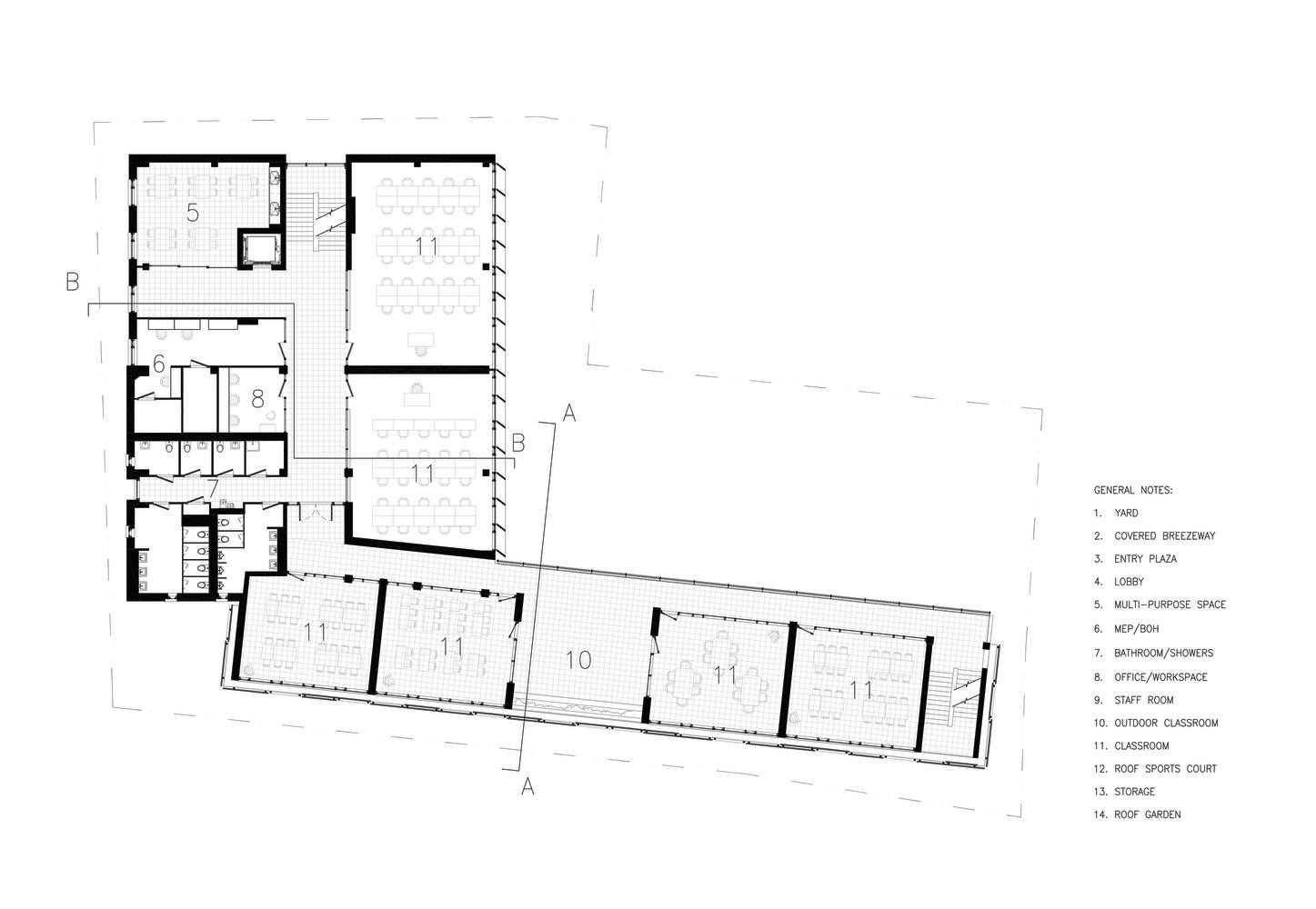

The building’s overall structure follows a combination of both grid and radial organization. This is represented in Diagram 01. The primary movement of users within the space reflects the radial organization of the building, while secondary circulation of users aligns with the grid formations. Initial user interactions with the building’s interiors occur at the primary points of entry

PHNOM PENH, CAMBODIA

and exit. This building exhibits an oblique approach to user arrival, utilizing it’s angular composition to create multiple experiences of arrival. Vertical circulation via stairways is concentrated to the Southern foremost side of the building. Use of technology is limited due to the project’s budget, and is mostly reserved for mechanical systems applications.

Throughout the design of both the interior and exteriors of the building, predominant surfaces exhibit a common linear grid motif. The facade features a grid of curtain walls and louvers. These patterns are mimicked in the interior flooring and ceiling material selections: a square ceramic

tile and a staggered layer of bamboo. This is demonstrated in the conceptualization of Figures 01-03. The materiality also celebrates the history and culture of the surrounding vernacular. Pictured on the right is a sculptral wall that portrays this technique.

Public spaces make up approximately 10% of the building’s overall square footage. Semi-private spaces account for roughly 70% and private spaces account for 20% of the square footage. Public spaces are centralized within the building’s structure, while semi-private spaces make up the perimeter of the building. Private spaces are congregated together on the Eastern side, as shown in Diagram 02. Both private and semi-private spaces remain adjacent to public spaces in order to ensure ease of access. These patterns remain true, despite the change in floor levels.

Utilization of natural light is reserved for the most commonly used spaces such as circulatory halls and classrooms. Storage, utility rooms, and restrooms have limited natural light access to ensure privacy. As shown in Diagram 02, the majority of the classrooms within the facility face the cardinal direction in which most natural light is penetrated.

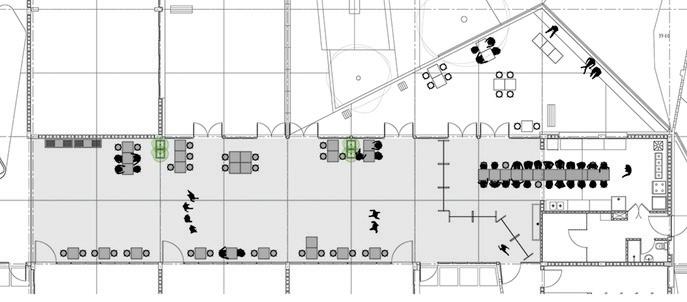

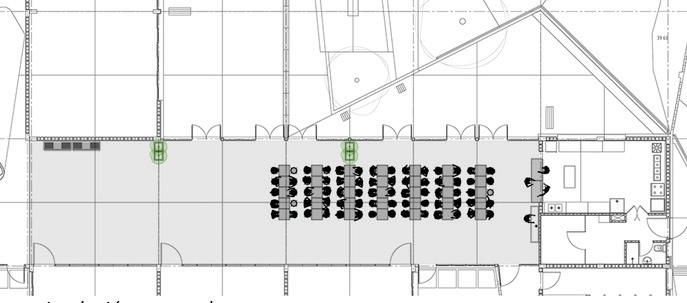

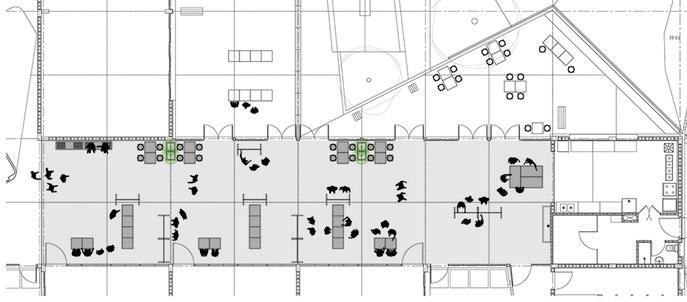

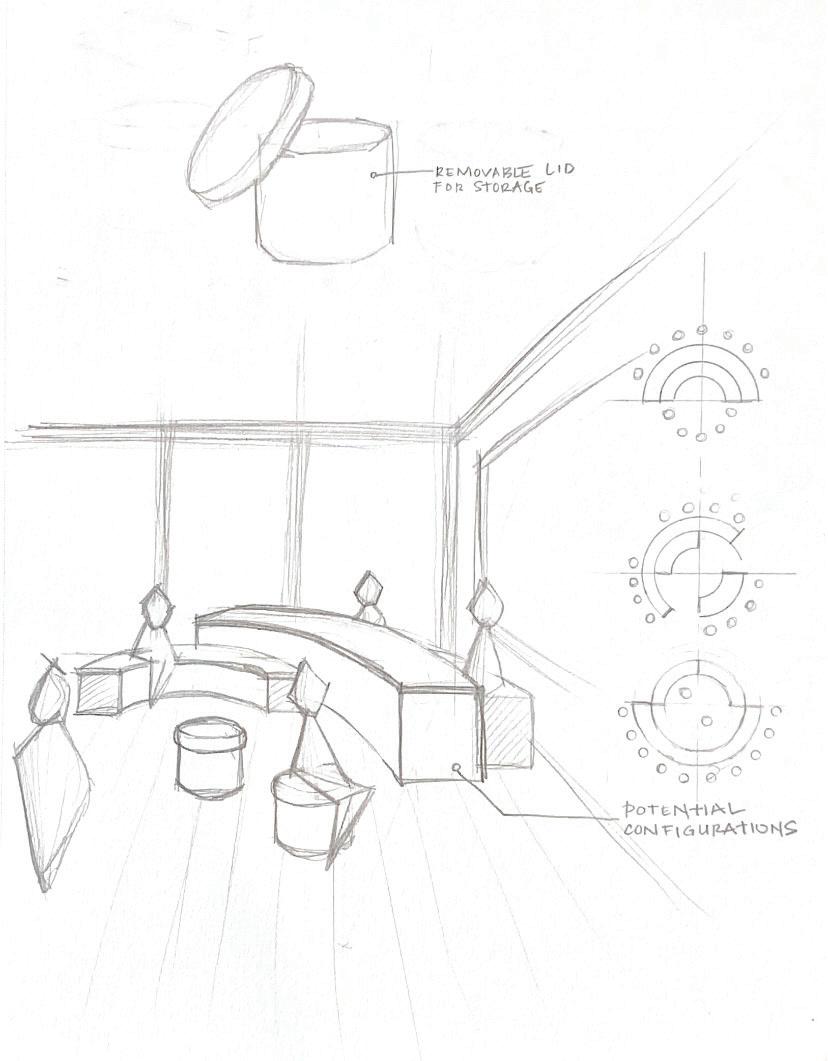

Furniture arrangement within the individual classrooms varies depending on the function of each room. However, there is a noticeable pattern towards clustered and linear arrangements within each room as shown respectively on point A and B of Diagram 02. General furniture selection is minimalistic in form and function and caters to the diverse user groups of the building.

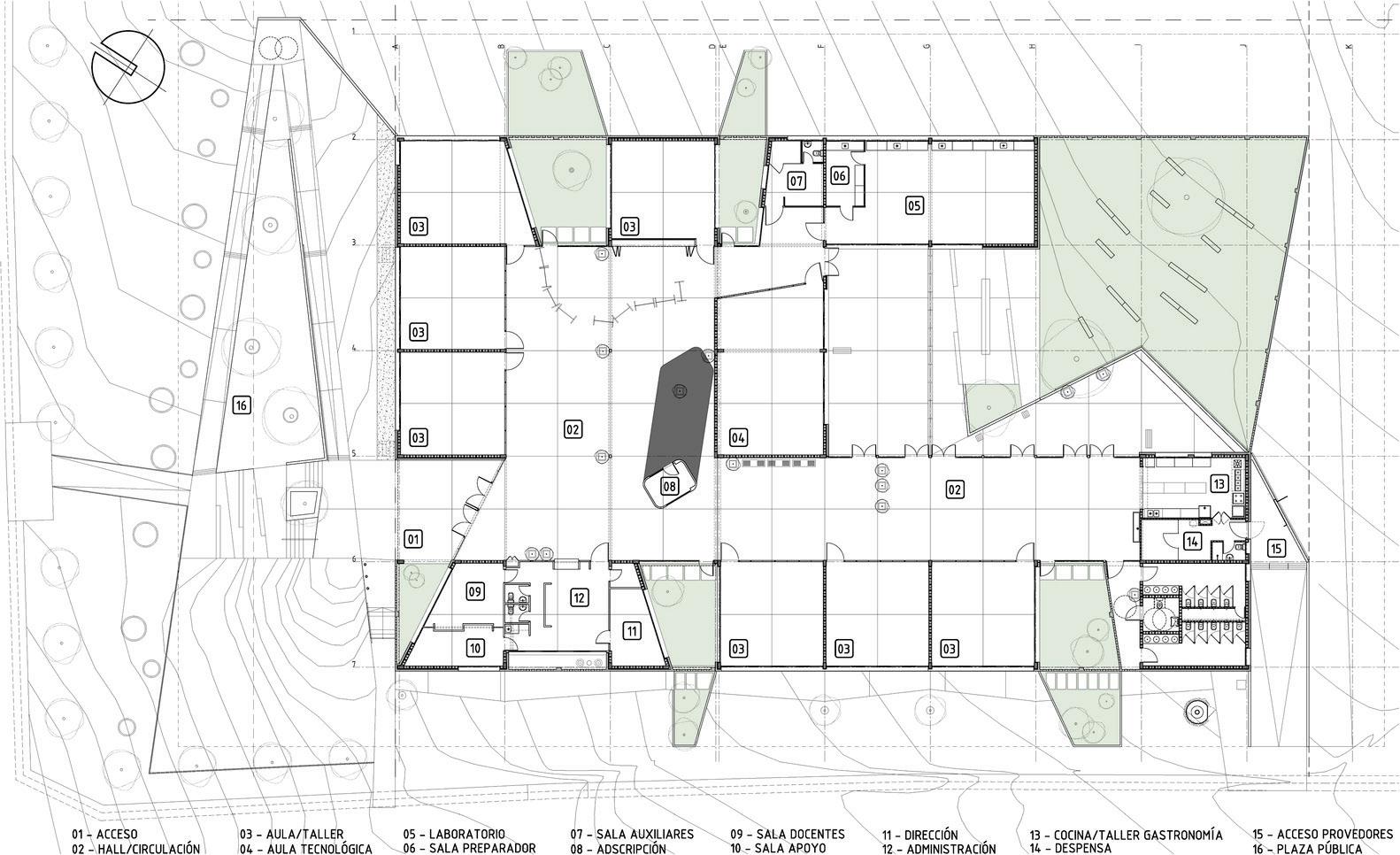

This design of this facility follows a modular grid system for the organization of elements within the plan. This is shown in diagram 03. Both primary and secondary circulation of users emulates this grid pattern as well. Access to natural light and outdoor learning spaces are prioritized for every

classroom space in order to promote a productive and healthy learning environment. These outdoor learning environments follow a pattern of dissection within the grid. This creates visual interest in the structural design, and helps to eliminate any notions of a “boxy” feel to the interiors.

DIAGRAM 03

KEY Grid Organization Green Spaces

Secondary Circulation

Primary Circulation

Approach/Departure

All spaces, both public and private use, are designed to be adaptable to a variety of furniture arrangements. These layouts can accommodate a variety of functions depending on the range of desired uses assigned to the space. These functions are a direct result of the users needs within the facility. For example, the study hall, can also act as a formal assembly place, when needed.

Service/Utility Spaces

Exterior Spaces

Specialized Classrooms Administrative Spaces Workshop Classrooms Circulatory/Common Spaces

Diagram 04 depicts the utilization of space within the organized grid system. Roughly 35 % of the square footage is dedicated to outdoor learning environments within the facility. About 27.5 % is used for circulatory and common spaces. Indoor classrooms are divided between specialized rooms (10 %) and workshops (17.5 %). Administrative facilities and utility rooms make up another 5 % of the square footage respectively. In terms of spatial relationships, publicly used spaces are centralized within the building while semi-private and private spaces encompass the perimeter. All classrooms are ensured adjacency to both outdoor learning environments, as well as common spaces, which can serve the dual purpose of both circulation and collaboration. Service and utility room such as restrooms are placed in proximity to the different concentrations of user groups. For example, the primary restrooms are located at the end of a common space for easy access to students, while the restrooms set for administration are set within their offices.

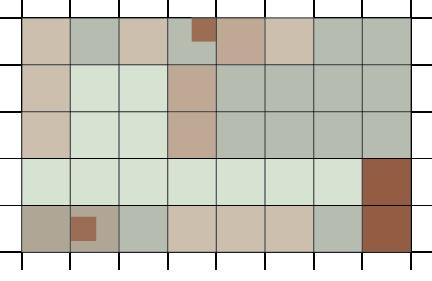

Materiality is managed according to efficiency and availability. Repetition of forms in a grid pattern is a common motif, angular cuts dissect this grid plane to provide visual interest, and break the box mold.

As a result of the social justice nature of the project, implementation of technology within the facility is not a priority in design considerations.

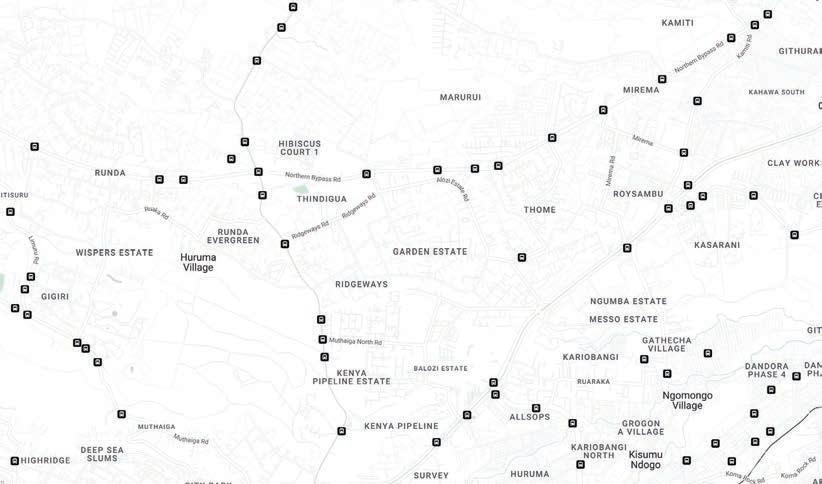

The project site is located along Alozi Estate Rd. in Nairobi, Kenya. This address is situated in one of Nairobi’s Northern suburbs called Garden Estate. This suburb and the surrounding communities represent the amalgamation of both local and global urban concepts. This is a result of native cultures merging with international trends and colonial impositions. Varied housing and architectural typologies emerged from this convergence to form a richly diverse vernacular of the surrounding built environment.

This particular site is ideal for the scope of this project primarily because of its proximity to the target user groups. The suburb in which it is located and the surrounding localities make up a range of backgrounds and income levels that align with the demographics of the student body. The surrounding topography and lack of harsh weather conditions also contribute to the effectiveness of the site.

Range of Angles at Which the Sun Sets Annually Range of Angles at Which the Sun Rises Annually Range of Positions the Sun Takes Throughout the Day

The building is situated on a plot of land solely utilized for educational purposes. These school grounds include multiple playing fields, adjacent boarding facilities, and ample parking for both buses and cars. The topography is abundant with vegetation and reflects the overall climate of the surrounding geographic area. Because the site is not located directly within Nairobi’s central business district, it does not receive as much

impact from the urban micro climate within the city. The general geographic location is directly adjacent to the equator resulting in two annual seasons: wet and dry. Temperatures do not fluctuate greatly, but average precipitation rates vary greatly depending on the season. The proximity to the equator also results in an acute angle of sunlight nearly year round. The range of the sun’s path is demonstrated in Diagram 05.

The site is situated in a centralized location relative to the Nairobi network of bus stops. The nearest stops are along the Northern Bypass Road as depicted in Diagram 06. Also depicted in Diagram 06, are residential suburbs, dining options, and schools in proximity to the site. These suburbs along with major roads and highways are the primary contributors to the noise pollution that the project site faces. This is shown in Diagram 05. The average wind speed in Nairobi is 15 mph. This speed does not affect the project site in any notable way.

Diagram 07 demonstrates the physical site plan of the project and its relation to the different types of user access. Buses and cars take the same route to enter and exit the site, but drop off of students is done along different paths. Car parking is located along the perimeter of the Southern side of the building. Bus parking is located farther off-site along Alozi State Road. Pedestrian access is through designated paths that lead up to the building as indicated in Diagram 07. Pedestrian access can also be achieved from the Northern end of the building through the playing fields, although no paths are marked in this vicinity. The perimeter of the site is enclosed through a system of fencing and hedges. This is for both safety and security purposes.

These localities represent possible locations of the residencies of the targeted user group. These suburbs reflect the variety of household incomes of the users.

KARIOBANGI

Kariobangi is a low-income residential suburb approximately 4 km southeast of the Garden Estate Suburb in which the site is located.

KASARANI

Kasarani is high-income residential suburb approximately 4 km east of the Garden Estate Suburb in which the site is located.

KOROGOCHO

Korogocho is one of the largest slum neighborhoods in Nairobi. It is situated about 4.5 km southeast of the Garden Estate Suburb in which the site is located

These nearby institutions represent the previous schooling that the primary user group of this project might have received. These are all primary schools in which the student body of the client might have attended. Their location is relative to the project site, and their curriculum and teaching methods align with the goals and objectives of the design of this new institution.

NOBLEGATE INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY

This is a private institution for students, ages 3-14. They utilize a holistic approach to their curriculum that caters to diverse learning styles.

KIGWA RIDGE SCHOOL & MONTESSORI CENTER

Kigwa is a primary school and Montessori located in the Ridgeway Suburbs southwest of Garden Estate.

WESTWOOD PREPARATORY SCHOOL

This school is located in Garden Estate along with the project site. Students at Westwood range in age from toddlers to middle schoolers.

The existing building belongs to the client, Braeburn, and is currently being utilized by as school for students ages 2-18. The structure itself is very unique, with roof lines that radiate from two separate points. This results in a primarily external load, with nearly all the walls bearing the load. Structural column placement follows an elliptical pattern as indicated in Diagram 08. These columns are either pre-cast or cast-in-place concrete. Bay sizes range between approximately 8 and 12 feet spans. Trusses span under the atrium roof as indicated in the exterior view pictured above

Diagram 08 indicates the potential vertical circulation within the building. Stairways are located directly adjacent to areas of primary circulation. A large ramp follows the line of centralized structural columns and acts as the primary vertical circulation between levels one and two. Due to the distance and slope, it is presumed that the ramp is handicap compliant.

The exterior of the building is a thick stone wall, both plastered and painted Nearly all ceilings on the first floor consist of rough cast plaster on reinforced concrete slabs with smooth plaster margins. Some of the administrative rooms have a smooth lime plaster ceiling finish. Ceilings on the second floor are primarily 12mm painted chipboard on stained softwood rafters and steel purlins. All walls are lime plaster with a finish of 3 coats of vinyl paint. This excludes the existing restrooms which have ceramic tiles that run 20002100 mm high up the walls. Skirting selections include painted softwood, coved cement, and porcelain tile. The flooring within the building consists of 2mm vinyl tiles on 40 mm sand cement screed. This again excludes the restrooms which utilize non-slip porcelain tiles on the same subfloor.

DIAGRAM 08: LEVEL 1

DIAGRAM 08: LEVEL 2

Due to the proximity to the equator and the overhang of the roof, direct sunlight penetrates the building primarily through the east and west windows, however indirect light is utilized by all interior rooms.

Passive ventilation occurs between the two primary structures in a clerestory fashion. Depending on window operability, cross ventilation can be achieved mostly through the north and south side of the building. The building orientation is designed so that the majority of natural light and heat penetration occurs at the smallest point of the facade. There is an integral sewage system and separate gray water system that includes intermittent inspection chambers throughout the permit er of the building. There is a septic tank with a lift system that drains both sewage and gray water off site or to a municipal sewer.

The overall floor plan and structural elements follow an elliptical datum. The roof is in line with the cardinal directions and follows two radial center points located north and south of the building. The building follows a relative symmetry on either side of these points. The void space within the atrium is balanced by the cluster of interior spaces around the perimeter. The repetition of window and classrooms creates a rhythm within the interiors of the building.

LATITUDINAL SECTION

EASTERN ELEVATION

As indicated in the Eastern elevation and latitudinal section, the level one starts at .15 meters, the second level starts at 3 meters above the ground floor, and the deck height is 6 meters above the ground floor. Fenestration elements follow a linear pattern. Window top heights are consistent with each floor level, although sill heights and widths vary. Fenestration is exclusively rectangular with no curved openings penetrating the building envelope. Massing heights and shapes vary relative to the roof line. Window operability is unknown, but manual operability is assumed based on the geographical region. All windows are design in approximately nine modular systems placed throughout the facade of the building in addition to the interior hallways and circulatory spaces.

The art of beading is an integral part of the culture throughout Kenya, from the plains of the Masai Mara to the cityscape of Nairobi. Representing tradition, communication, and unity, all beads are singularly special, but together they symbolize a new idea at large.

The Swahili term KIFUNGO represents the bond of stringing together tokens of culture. This is synthesized through the relationships students form, and the curriculum that is retained at the school. Just like the diverse user group of the facility, beads differ in shape, size, and color. Their bond is what ties them together, both literally and physically, to create a integral student body. Similar to the personal ornaments crafted through bead work, this bond is visualized through radiating concentric circles in an array of patterns, cascading forms, and bright colors.

The following diagrams are based off of the four predetermined categories of spaces: learning, collaboration, assistance, and socialize. Each color corresponds with a category as indicated at the top of Adjacency Diagram 01 Because of the unique structure of the building, and its relationship with natural light, the primary considerations for spatial relationships were proximity to related functions These initial bubble diagrams do not consider a change in levels of the building.

No matter their background or beliefs, whether they are native, or international, students seek to honor the culture of their heritage. When they commemorate their traditions, there is a sense of pride and belonging they experience. There is also opportunity to learn from different cultures, when exposed to them in a safe and welcoming environment.

Students will seek academic success throughout their entire school experience, and take the same habits with them after they graduate. There is an opportunity to motivate students through their classroom environment, in order to instill these habits and ensure an enriched future.

Some of the most valuable lessons learned are how to work with others and how to make friends. Whether its with their peers, teachers, or members of the community, forming relationships is a vital aspect of a school experience. Providing opportunities that promote collaboration ensures the achievement of fostering connections.

Community involvement is an integral aspect of this school experience, whether it’s from a guest speaker, to an organized event. It is crucial to develop key experiences that elevate the community integration and cater to its members as a secondary user of the space.

Some of the most difficult problems students face is a result of a lack of self-confidence to succeed. By implementing opportunities for feedback, validation, and assurance, the school is able to ensure the confidence of its users, even post=graduation.

Brightly colored, statement lighting fixtures made of locally sourced beaded tapestries will create concentrated focal points of cultural representation.

Students experience a subtle representation of traditional Kenyan patterns through the furniture selections and arrangement.

International food will be integrated into the dining hall experience, and supported by the cafeteria’s signage, and seating variety.

An innovative classroom experience that targets specific career fields helps to ensure students have the skill sets needed to join the labor force. Agriculture, being the largest economic sector, in Kenya, is a great opportunity to create a useful class room experience. Harvests from the school’s agricultural center can be directly utilized by the school dining hall to further create a self sufficient facility.

Relying on the support of peers to fill in the gaps of a teacher’s lesson is mandatory to the success of the school. Media classrooms in which groups are predetermined by seating arrangements makes this process more efficient.

A modern way to get students involved in the progression of their academic careers is to make them feel in control of the process. A student supply store centered in the library can help students to not only check out the items they need, but feel empowered while doing it.

The best way to ensure students form healthy and long-lasting relationships is to give them a variety of opportune spaces in which to do it. Concentrated areas of seating within social spaces is crucial to facilitating this. Allowing students to pick and choose a “home base” gives them the confidence to branch out with assurance that they can always return to their favorite lounge chair or nook.

A classroom setting that can be altered in order to facilitate collaboration is crucial to fostering connections amongst peers, teachers, and any classroom guests.

The layout of some cafeteria seating allows students to see how their food is prepared and cooked for them. Including students in this experience allows them to feel involved. This is also a great opportunity for students to learn about different or their own traditional cuisines.

An auditorium and meeting hall that is capable of adapting to different events and functions allows the members of the community to better utilize the facility. It also allows students to take advantage of educators outside the school.

School can be challenging, and seeking help can be intimidating. Creating an adaptable and inviting environment in which students can get one-on-one help from their peers is the perfect way to give some students the confidence to maintain their education. Comfortable seating, with semi-private partitions further enables this.

School pride is great way to promote the confidence of the entire student body. Creating innovative experiences of display for trophies, awards, etc. is a beneficial opportunity to promote school pride. Placing this experience in proximity to the primary entrance to the building guarantees students will get a visual reminder of school pride daily.

In order to achieve a holistic user experience that represents the surrounding culture and vernacular, all materials, furnishing and finishes will be sourced locally when possible.

In order to achieve a holistic user experience that represents the surrounding culture and vernacular, all materials, furnishing and finishes will be sourced locally when possible.

In order to achieve a holistic user experience that represents the surrounding culture and vernacular, all materials, furnishing and finishes will be sourced locally when possible.

In order to achieve a holistic user experience that represents the surrounding culture and vernacular, all materials, furnishing and finishes will be sourced locally when possible.