The Image of Lewes

Ideas Study for the Station Approach

University of Brighton

School of Architecture, Technology and Engineering

Architectural and Urban Design MA

Rafael Grosso Macpherson AIM50 Masterwork

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my gratitude to Sarah Stevens and Rob West for their support and continuous supervision and guidance during the course and this masterwork in particular. I would also like to thank my fellow colleagues at university, who help me develop the necessary skills to produce this masterwork. All the same, I would like to thank Paul Fender for his altruistic contribution of the baseline model that helped me build my own design.

Finally, I would like to thank my family, friends and partner for their continuous support.

Acknowledgements

PART 1. INTRODUCTION

The Angle

Looking Back

Purpose of Masterwork

Introduction to Lewes

The Station Car Park Site

PART 2. APPROACHES TO DESIGN

Moving Away from Neoliberal City Production

Proximities and the ‘Right to the City’

Density and Diversity

Environmental Perception in the Design Process

Sense of Place Against Placessness

PART 3. PLANNING CONTEXT

The Design Process in Planning

Policy Review and Precedents

PART 4. CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS

Methodology

Green and Blue Infrastructure

Views and Building Heights

Land Uses and Access Parking

Lewes Neighbourhood Development Plan

Context Through Kevin Lynch’s Eyes

Design Principles Beyond ‘The Image of the City’

PART 5. DESIGN PROPOSAL

Framework Development

Iteration of Concept Plans

Scenario 1. Station Approach and New Southover Road

Scenario 2. Station Approach and Trees

Scenario 3. Station Approach and Reimagined Southover Road

Next Steps and Conclusion Bibliography

Table

Contents 1 1 00 2 3 4 5 6 7 00 8 9 10 11 12 13 00 14 15 16 00 25 26 27 28 30 31 32 33 35 0 36 37 38 42 44 46 48 0 49

of

INTRODUCTION

2

The Angle

Cities of today have focused their recent ‘life’ in maximising economic potential above all and this is a constant in the way future cities are designed today. We, urban inhabitants, don’t escape from this trend and have increasingly adhered to a global economic phenomenon based on economic production. But I think that the reality of some of its consequences, like climate change, solitude, lack of housing, food, water and land, etc. are catching up and causing harm to our lives.

I am concerned with how most cities are yet produced in mass, expanding indefinitely through making an inefficient use of land and other resources, still failing to change towards a more sustainable way of developing, designing and managing urban habitats. But not only that, another unfortunate consequence of current city making is that the resulting environment becomes standardised, feeling cities very similar to each other, looking almost identical, regardless of where in the world they are. In many occasions, they lack any relational, historical and concern with its place and its people, which leads to a disengagement of people and place. This also contributes to people disengaging with their habitat, as the experience of place is not memorable, identifiable and difficulty creates a sense of belonging. I find the most prominent constant in most cities is the car and its infrastructure, a useful tool for many, and a dreadful problem for all.

I have also been inspired, through the course, by many designers and urbanism academics that have focused on placemaking stretching the boundaries of the current urban design system by not being driven strongly by the neoliberal impulse. Good design for a good purpose is not necessarily impossible. Some of the examples that have influenced my work are alternative to average urban developments and start to show how a more human urban environment could look like.

There have been many efforts in the planning and design specialisms in addressing many of the issues around social justice, comfortable living and working environments, car dependency issues, etc. but the stepping stone is a system, which does not seem to allow meaningful changes for the delivery of city for people’s delight.

For this masterwork, my standpoint is to think of people and place first, and I would like to explore, test and stretch ideas that, through design, contribute to the eradication of an unbalanced urban environment for people.

3

Platform viewed from Station Bridge. Car Park, bank with trees and Southover Rd. bridge at the back. Source: Own.

Looking Back

In the last course, I reflected on and used two photographs in many occasions to illustrate some of the issues of the urban environment that matter to me.

The picture in black and white represents a contemporary urban environment that is out of date already. It is for people that are car-dependent as result of the urban and architectural design decisions of the past and it follows an economic, social and environmental model that is unsustainable. Spaces are over dimensioned and the sense of place is poor, having no regard to the preexisting landscape.

On the other hand, the photograph in colour evokes me feelings of living in the geography, not against it. Whilst it could be seen as a simple picture of a house, I believe that it counters the previous image with a soft approach of understanding space, geology, topography, water, habitats, time, etc. and making place (and peace) with these.

Some of the aspects from this masterwork develop from my interest in geography and landscape, and the need to move away from an unsuccessful urban habitat.

Top: A detached house, stream and lane on the edge of the village of West Burton. Source: Own.

Top: A detached house, stream and lane on the edge of the village of West Burton. Source: Own.

4

Bottom: Aerial photograph of Sanchinarro, a 2000s mixed use development in Madrid. Source: Google Earth.

Purpose of Masterwork

The purpose of this masterwork is to critically analyse Lewes town and a specific site, the Station Car Park, as well as to develop a cohesive framework and scenarios for its redevelopment based on the lessons learned.

The path towards a conceptual urban design scenario includes an understanding and critique of the relevant local planning policies applicable to this site, assessed from my own ethos. In order to strengthen critical reviews of policy and the site, I support arguments and design decisions with academic theory and precedents.

Another purpose of the masterwork is challenging myself and what I have learned so far, as well as expanding horizons. Therefore, I have consulted and incorporated relevant academics into the analysis and discussion of the issues and opportunities as well as in the germination design proposals.

The result is a well-reflected independent design assessment and set of scenarios for the redevelopment of the Lewes Station Car Park.

5

Access to Lewes Station Car Park and Depot Cinema gardens. Views to the North from the Station. Source: Own.

Introduction to Lewes

Lewes is a historic town of 16,000 people in East Sussex, located 9 kilometres inland from the coast and only 12 kilometres north-west of Brighton. It is the largest town in the South Downs National Park, an area of prominent chalk ridges, hills and valleys. The town is strategically located at the point where the River Ouse cuts through the South Downs.

An important aspect of the character of Lewes arises from its topography and setting, as high chalk hills and cliffs circumscribe the town. The settlement had a significant connection to the River Ouse due to trading of many industries in history, from brewing to ironworks. The local economy nowadays is based on retail, small locally-important industries (brewing, creative arts, craftmanship, and high-tech businesses), as well as other services. It has a privileged location between major cities such as Brighton, Eastbourne and London, with direct rail connections to all three.

Due to the town’s convenient access to nearby services, the countryside and other cities by rail, Lewes has become a popular town for many, which has led to a rise of house demand and prices beyond local incomes. Furthermore, as population increases and existing industrial land is re-developed for housing, employment space falls short and become unaffordable and not fit for purpose.

Lewes has an important challenge ahead in delivering adequate and affordable places for living and working, as well as contributing positively to its community, also making its landscape and culture worthy of the designation as National Park.

The town has been historically known for being the capital of Sussex for a period, being an important market town in the middle ages, and more recently for having one of the most impressive Guy Fawkes Bonfire events in the country, which are rooted into Lewes’ culture and communities.

Today, Lewes is a town of rich and diverse architecture and materials, with a close relationship with its landscape. It forms part of the South Downs, constrained by its topography, its breath-taking views and its river. The town sits in an area occupying part of the flood plain and the hills on both sides of the river. Historically, the flood plain and the river were used for agriculture, for industrial and trading purposes, and it still remains as such in some regard, although industrial land is being lost to residential development. Homes would normally sit on higher ground level due to flood risk constraints but nowadays, demand for housing and flood defences engineering has led to housing in flood plains protected with barriers.

6

Location map. Source: Own

The Station Car Park Site

Why Lewes? Why this site?

I decided to focus my masterwork in the context of Lewes as it is a perfect location that combines multiple housing, employment and environmental challenges that need addressing as well as complexities that will help me develop in my research of urban design.

This site drew my attention 4 or 5 years ago, through work, as I have been involved in the assessment of planning applications in Lewes for some time now. I have known the site from many vantage points, as a rail service user, a car park user, a visitor, a professional, a student, with friends, colleagues and on my own, during the day and night, during weekdays and weekends, winter and summer… The experience of the site has been extensive and a few years ago I started questioning why this site in such desirable location is so poorly treated, being a half-empty car park. I have enjoyed the beautiful conversion of the Depot into a cinema, restaurant and open space, and I experienced the drastic contrast of the Depot, which contributes so greatly to people’s lives in Lewes, and the harsh and empty of life space that sits just beyond the walls of the Depot.

Later in my career, I realised that part of the car park site was allocated by planning policy for residential development, to my surprise. My reaction was bifold: I thought that this allocation represented an excellent opportunity to do things right and repair the town through new design and development. On another hand, my expectations for something really inspiring were low, as most residential developments locally were mediocre.

It is now that I have an opportunity to expand my knowledge of the site, planning and urban design issues of Lewes, and to build the first stepping stones of what could become a successful addition to the town.

7

Southover Road

Station Bridge

APPROACHES TO

Moving Away from Neoliberal City Production

Proximities and ‘the Right to the City’

Environmental Perception in the Design Process

Sense of Place Against Placelessness

8

Moving Away from Neoliberal City Production

We could spatially identify where and how the city has been put to a use, a form, or a condition, to meet the interest of the market in production. Cities’ contribution to the economy is part of the reason for their own existence, but problems surge when aspects necessary for quality living disappear from the environment or become relegated at expense of those that prioritise economic production, with the devastating effect of an impoverished society and environment.

Chinchilla (2020) rightly points out that urban spaces are designed (physically and legally) for productivity: to facilitate delivery of goods, drive and park to work, advertise a business... but it becomes a more hostile place for those activities that are not linked to productivity: sleep, drinking water for free, breathing clear air, enjoy without paying are challenges in current urban environments.

In my view, the disfunction of the system is well illustrated in the widespread development tradition of disregarding the efficient use of land and other resources, through developments of low density detached and semi-detached housing, which lead to a sacrifice of everyone’s resources for the benefit of few. There are many further examples of poor decisions, which span from the unfortunate weight given to people (the final user) to private car ownership, strict infrastructure and building standards, poor municipal services and management, properties as financial assets… to the lack of meaningful consideration to climate change, affordable housing, communities, etc.

Chinchilla (2020) explains that current urban spaces have been made in a context in which the needs of a particular group of people have been prioritised and the rest are ignored. In the Lewes context, travellers/commuters have been prioritised, and especially those using cars as part of their transportation. The rest are almost absent from this environment: there is no housing, no workspaces, no play areas, etc. Regardless of use, the car park is a hostile space for most human-centred activities.

We design buildings and cities, but these design us too. Design has a crucial role in constructing future societies and strengthening the balances within, as people and place are not as separate as we may think in physical terms, but one is the result of another and they correlate constantly and continuously in time (Anne-Marie Willis, 2006). In this context, the designers’ mentality of today will be embodied in the places of tomorrow, thus constantly influencing future inhabitants and designers. It is our power now, to think on whether the space that we have before us is contributing towards the future society that we envisage and we want to shape. Re-balancing injustices with society and the environment should be, in my view, an inherent part of designing a new intervention in town today, for our benefit in the future. Therefore, it should break away from the urban elements that we consider to be out of date and not found in imagined future habitats.

‘There is an epidemic of poor health due to people living their lives indoors, sitting inside mechanically ventilated buildings with artificial light, transporting themselves everywhere in cars’

Quote, David Sim (Soft City):

9

Lewes Station Car Park as an ‘anywhere’ part of town. Views from Station Bridge to the East. Source: Own.

Proximities and the ‘Right to the City’

Carlos Moreno (2022) wrote ‘La Revolución de la Proximidad’ or ‘the revolution of proximity’, where he identified the primacy of private cars, asphalt and hard environment as contributors to the de-humanisation of cities, due to the disequilibrium between the environment created with cars and the loss of social interaction. In his reflections, he identified the proximity as a virtue of the city and the distance as a vice.

Le Corbusier (La Ciudad de Los Quince Minutos, 2023), on the contrary, agreed that the city and its zoning was the ideal program for planning a city, as humans would live, work and recreate in distant well-defined areas that would not feel so distant due to the use of private cars and the associated infrastructure that would facilitate movement. It was thought then that distances would be overcome by technology and infrastructure, but nowadays we have realised that distance is a problem as it does not only lead to negative impacts of pollution, use of land, etc. but to the waste of time of those moving with the counter-productive effect of loss of social interaction, care and enjoyment of living in a community. All of these, detract from the quality of life of humans and it is my view that urban design and development in general should take an approach in which it facilitates living in short distances to our daily needs as well as it discourages unnecessary private car travelling.

I find Moreno’s diagnosis to be fully applicable to the chosen site in Lewes, as it is a large car park that facilitates traveling long distances by car, therefore cutting distances, but conditioning the time that citizens spend travelling, which increased significantly since

the car became available and dictated in which ways we plan and live our cities. This car park has also clear implications, mostly negative, on the wider environment of Lewes. It contributes to air and noise pollution and has resulted in a tabula rasa in which the pre-existing natural environment is non-existent.

It is important to understand the reason why the car park was there in the first place: it serves the railway station and it helps connecting those living or working in in less accessible areas around Lewes and benefitting from a multimodal car and rail travel.

Lewes, due to its size and relatively compact centre, could be considered a ‘15 minute city’ as it has many services needed by people in a daily basis. However, what I am assessing this time is how this site in particular, in Moreno’s context, contributes towards it or against it. How can the Lewes Car Park Site make Lewes flourish as a town where all daily activities are accessible and available within public transport, walking and cycling distance?

I believe that the car park could contribute more towards a ‘town of proximities’ and with it, embrace citizens’ right to the city, the right of appropriation of the city: to access, to occupy, to use and to maximise the public benefits of the city and its public space rather than being an area for a prioritised group of people.

10

Constituents of the Paris 15-minute city. Credit: Michael. Source: RIBA wesbite.

Density and Diversity

David Sim (2019) has been an important influence in this masterwork and I find his ‘soft city’ approach to urban design that, if adopted, could help many cities to be more socially sustainable and make a more efficient use of land.

Soft City explains that the fusion of density and diversity increases the chances of useful things, places, and people being nearby. This leads to likelihood of symbiotic relationships: improve reciprocal access to employers and employees, teachers, schools and students, etc. Following from Moreno’s diagnosis, the space is thought in terms of time, and it explains that there are many ways in which time can be measured: in steps, cycle rides or train rides, and not by car trips. Other people may take other less-obvious ways to measure time and distance: the duration of a song, a film, a laundry wash, etc. which humanise the experience and value of time, reflecting, in my view, that time is more valuable than just minutes or hours, but as actions, relationships, moments.

From Sim and Moreno, I take the importance of what can be done in a period of time, rather than the time itself, and I agree with Moreno’s concept of the city of the 15 minutes that having all daily needs nearby is a success for saving time and enriching life with interaction, relations, moments… These refer to spaces and distances that are of a human scale and diverse enough as to mix and combine for a complete life.

Sim refers to the success of Vauban (a mixeduse development in Freiburg) in achieving social diversity through designing diverse spaces and

buildings: from walk-up flats (3-5 storeys), to town houses. But also, with several interpretations of active ground floors, from doors to the street, front gardens, defensible spaces, shop windows, business units, outside stairs, decks, galleries, etc. And also, with a mix of spaces, from private front or rear gardens, terraces, roof tops, loggias, balconies, courtyards, some public some private, some, in between. And what structured all: a green corridor and a large plaza.

Chinchilla also states that there are not many places for care in cities. Playgrounds are mentioned as defined and fenced spaces for children that determine the type of care that this space can offer: one focused on surveillance and safety. But what the city is missing is valuable interactions of people (including children) and the personal and imaginative management of risk and socialisation. Therefore, both carers and people looked-after, need from spaces that do not predefine the sort of activities that can take place and that maintain curiosity alive and there is a small doses of unpredictability.

TAKEAWAY

What I take from Sim and Chinchilla is that the diversity of places should be a rule in most designs where social sustainability is an objective. But also, that it is in the mix and flexibility of spaces where many activities can take place, including those that we haven’t designed for. A rigid design would only allow certain activity and not others.

11

Some design principles for a soft city. Source: David Sim, Soft City

Environmental Perception in the Design Process

The image of a city was conceived by Kevin Lynch (1982) as a mental construct of the environment, a result of a two-way process between observer and environment, therefore images could differ from one person to another, as people would give elements different values. When there is a common image shared by a group of people or community, it could be called ‘identity of place’, according to Montgomery (1998).

I work with the above concepts of image and identity of place as outcomes that the urban design process should aim to when deciding the structure of a city or an area in particular, in order to prevent a city being an ‘anywhere place’.

There is an argument for places that result coherent to observers in the present, therefore, when standing on a particular place, it is easy to understand the environment around, and when deciding to explore, the route appears obvious to the observer as the design of the environment is suggestive.

An interesting argument is the addition of complexity and uncertainty in the mix through design. This is the case where the environment is sufficiently complex for the observer not being able to make a mental spatial structure. In this case, the observer needs to get more involved in the exploration as travelling through the environment presents them with additional information suggesting more and more.

TAKEAWAY

I am of the view that a balance between legibility and mystery is an adequate way forward in designing at the Station Car Park in Lewes. I suggest that design decisions should be made with an understanding of the town’s identity and the elements that form Lewes, but being careful at design stage so buildings and spaces in between are not reduced to the production of signs and responses, but they perform a deeper function to town.

Analyse the elements that conform the ‘Image of the City’ according to Kevin Lynch: landmarks, nodes, districts, edges and routes.

Adaptation of an environmental preference framework by Kaplan & Kaplan. Source: Public Places, Urban Spaces: the dimensions of urban design, by Mathew Carmona et at.(2017)

‘If the environment is visibly organized and clearly identified, the citizen can impart his own meanings and connections to it. then it would become a real place, remarkable and unmistakable.’

Mental

of the

and

of

12

Quote. Kevin Lynch

map

Station

High Street area

Lewes. Source: Own.

Sense of Place Against Placelessness

This feeling of ‘sense of place’ has been used by designers to measure the distinctiveness place. This distinctiveness encapsulates abundant information about a place: how it functions, how it is perceived by people, how to move around, a narrative of its history, its people, its ecosystems... The information contained through place could be significant, and depending on the quality of that particular place, the information could be more or less legible.

But the physical environment has to be accompanied with life, activity, in order to give a function to place and become part of the people’s lives. Meaning is also important, as places contribute to the feeling, importance and overall personalisation that we make of place.

Sense of place is what I task myself to use to counteract the ‘anywhere place’ or placelessness, which result from the standardisation of the design process and focus on productivity. Another result of the neoliberal city production and governance embedded in our planning system.

TAKEAWAY

I find that in order to adopt a ‘sense of place’ approach to the Lewes Station Car Park site, I should focus on the physical environment (built and natural), but also give spaces a function that are meaningful to the town and its people so they can fill these places with meaning.

13

Adaptation of John Montgomery’s diagram of how urban design actions contribute to sense of place. Source: Public Places, Urban Spaces: the dimensions of urban design, by Mathew Carmona et at. (2017)

Lewes Station Car Park and suburban houses lacking a sense of place. Views to the East. Source: Own.

PLANNING CONTEXT

The Design Process in Planning Policy Review and Precedents:

14

The Design Process in Planning

The planning policy applicable to this site mainly consists of the National Planning Policy Framework, the South Downs Local Plan (SDLP) and the Lewes Neighbourhood Development Plan (NDP). Whilst all are applicable, the Lewes NDP is the policy document that is most specific to the town, therefore it would be subject of analysis in detail.

Landscape-led design

The SDLP has adopted a landscape-led approach to design, requiring design proposals to be strongly informed by an understanding of the essential character of the site and its context (the landscape), creating development that speaks of the location, responding to local character and fitting well into its environment (SDNPA, 2022). The SDLP also expects development to conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage of the area and create sustainable and successful places for people.

The above requirements are common in a contemporary set of planning policies in a protected landscape. It is however somewhat new that the planning policies set out the design process expected, guiding designers through a process that should take them to a solution that positively contribute to the National Park. Overall, the aim of this process is to strengthen sense of place, ensuring that the towns and villages of the National Park retain what is characteristic of these settlements and they not become of a diffused identity, which would erode what the distinctive towns and villages that make the National Park special.

In my view, this approach is useful, but it has an essential problem, and it is that it still does not solve the question of balancing conflicting factors and decisions in the design process. The approach to design is landscape-led, and therefore, landscape-biased. But what happens when the process results in a design that integrates well in the landscape, but fails, for instance, to promote social interaction, or incorporate passive house principles? What happens when the landscape evidence (based on the existing built environment) becomes an obstacle in a forward-thinking complex design process?

I can think of scattered detached houses being the traditional settlement pattern of a place, which the landscape-led approach would “require to replicate” if following the process literally. However, in contemporary urban design and planning, this approach would be challenged as an inefficient use of land. One could also say that detached housing contributes to segregation of communities, poor social sustainability and problems of affordability. Therefore, when should the landscape-led approach to design start and when should it end to ensure that settlements integrate with the existing landscape, but also contribute to making better places for people?

Neighbourhood Development Plan

The Neighbourhood Development Plan vision for Lewes follows the same approach, but emphasising the role of businesses and arts as part of the cultural heritage of the town. This evolution of the NDP landscape and design policies derive from the source of Lewes’s quality of place and living, resulting from the years by creative working industries, a radical and independent identity and a connection to its geography. Similarly, when tackling climate change adaptation, the NDP vision for Lewes embraces resilience and imagination, aspects related to the historic and present creative and working environment of the town. Interestingly, the vision also puts people first, when stating that people’s quality of living should be the most important matter in new development. This is ambitious in a policy document, where others in comparison do not mention in such emphasis ‘people first’.

It is however unfortunate that no policy covers well health and wellbeing as required outcomes of good urban design. They are only seen from an ‘access to the countryside’ approach, but not a design principle that should influence living and working places. However, I would challenge this approach in two ways:

• Work areas, not only residential, should benefit from access to open natural spaces, as people spend the majority of the day in their workplace.

• Access to the countryside is no the only way to deliver benefits to health and wellbeing. Internal and external spaces are equally important and they complement each other depending on weather. But more importantly, the way of living resulting from the development would be the most crucial factor when determining the quality of health and well-being. Having an active life of walking, cycling, socialising, etc. could be delivered through design, but planning policies barely focus on these.

These policy documents are rural-biased: the benefits of open spaces are not seen from an urban standpoint, but from a suburban and rural viewpoint. This could be understood given the rural nature of the National Park, but in some towns, such as in Lewes, policy has to be interpreted to ensure that health and wellbeing are factors considered in the design process. In this instance, the NDP better understands urban peculiarities of space and better deal with solutions than the Local Plan, when supporting innovative higher-density housing, and even suggests roof gardens as a solution. Notwithstanding this, there are numerous matters that require attention and are covered in this chapter.

Landscape-led approach to design simplified flow chart. Source: South Downs National Park website.

15

Townscape

Policy Review

Townscape NDP policies make a strong statement of what new development should prioritise: the most significant views of landmarks within the town and surroundings. It adopts a landscape-based approach, which I support insofar as it embraces the connection (mainly visual) of the urban space with the countryside, partly creating a physical environment for sense of place.

Notwithstanding this, the town is perceived by all senses and not only visually, which is the emphasis of this and most planning policies. Whilst we obtain most of our information through vision, the acoustic space helps in emphasising space, instead of objects. Smells, taste and texture are emotionally rich. All of these are absent in planning policy, yet they contribute to how we perceive the environment.

It is also my view, that the ‘social construction’ of the townscape and its character is sometimes missing. Again, policy focus much on the visual aspect of the ‘observed’ elements, but it does not mention the necessary ‘observer’, which varies in time, age, occupation, background, and gives meaning to what they observe, resulting in a variety of emotions. The observer will give meaning to place through their own perception.

TAKEAWAY

I advocate for a more diverse approach to the perception of place, in this case landscape/ townscape, which includes other senses and focuses too on the subject who co-creates the identity of that place together with the elements that conforms the town.

Extract from the Lewes NDP

16

Precedent

Wallands Primary School Rainscape is a sustainable drainage system retrofitted in the outdoor space of a school in Lewes. The design not only manages rainwater sustainably but also creates multiple sensorial and play opportunities. The drainage design is not only a positive element visually, but it is an experience for adults and children. Water can be reached by hand, it can be intercepted and interrupted, diverted, encouraging play and interaction between people and place. Water can also be experienced through sound as it falls on the ground and runs on a toboggan, from hard to soft surfaces. In this case, it has also resulted in a mix of surfaces that range in texture, emphasising touch.

Considering water is very important in Lewes, a town which is defined by its relationship with water, the River Ouse, its tributaries and the sea. Embracing water in the design would make the project speak of its place. When accompanied cumulatively with visual and other sensorial experiences, Lewes could maximise the potential for strengthening what makes it special.

All of these experiences of place contribute to what constitutes the landscape. It is not just what can be seen, but what can be perceived. A visual bias in the planning policy is understood, but not necessarily the only way to fully describe and construct place.

Wallands Primary School Rainscape. Source: Own.

Wallands Primary School Rainscape. Source: Own.

17

Living and Working

Policy Review

The NDP mentions the support for studios and workshop spaces, which follows from the intrinsic economic and social fabric of Lewes, based on creative industries and some manufacturing. Whilst I agree that the support for these working spaces is positive, it is also insufficient, as the NDP does not allocate land or at least proportions of sites for these uses. There are some employment allocations that involve large manufacturing, commercial and other light industrial activities, but there is no provision for small scale and independent work - the soul of Lewes.

My view is that mixed use developments should be the rule, and only some exceptional areas should be dedicated for residential or employment uses exclusively.

TAKEAWAY

When designing a new scheme in Lewes, especially in a highly sustainable location, as the Station Car Park, I would make efforts to incorporate work and living spaces that support one another and that are of a scale that facilitates small businesses to entrepreneur in Lewes. This entrepreneurial spirit is intrinsic to the culture and economy of Lewes and it can be reinforced through design.

Extract from the Lewes NDP

18

Precedent

A double-courtyard in Malmo creates two distinct outdoor spaces, inviting a variety of uses, and maximising opportunities for non-residential activities too, such as offices, shops, workshops or even a restaurant. Only guests have access to the private area, but it does not impede residents from enjoying the majority of the courtyard. Uses are layered in time: seasons, days and hours of the day define the activities and accesses to these places.

19

Illustration of a temporary restaurant in an inner courtyard of a residential block in Malmo. Source: David Sim (2019)

Housing Allocation

Policy Review

The site faces several challenges on its own: topography, boundaries, relationship with street and bridge, trees, railway, vehicular and pedestrian access, etc. However, the allocation policy adds more that could jeopardise appropriate urban design solutions.

• It remains car-dependant at allocting space for parking and gives no consideration to all the sustainable transport options nearby. Given the highly sustainable location, the starting point could be a zero parking scheme. I find that the proposed enhancement of cycle facilities would unlikely lead to the change in transport modes desired if new communities in this location remain dependant on cars.

• Low-medium density, likely justified on the avoidance of impacts to townscape. Given the concerns with roofscapes in town, perhaps a ‘low rise, high density’ approach could be more appropriate.

• The approach to access strategy appears to be for cars.

• Unrealistic expectations with regards to the retention of trees, as policy requires new accesse for cars from Southover Road and Station Road.

Extract from the Lewes NDP

Extract from the Lewes NDP

20

Precedent

Peter Barber Architects are specialised in designing low rise, high density houses with liveable streets. Some of these developments are characterised for bringing the width of streets below the standard found in highway manuals and making spaces shared for people, vehicles and cycles.

I find these examples inspiring and applicable to an extent to the Station Car Park site, as these maximise space, share spaces and integrate well in a wider low-rise urban area. They also create interest through curvature of routes, irregular-shaped open spaces and prominent corner buildings.

Donnybrook Quarter, London. Source: peterbarberarchitects.com

Moray Mews, London. Source: peterbarberarchitects.com Fleet Street Hill, London. Source: peterbarberarchitects.com

Donnybrook Quarter, London. Source: peterbarberarchitects.com

Moray Mews, London. Source: peterbarberarchitects.com Fleet Street Hill, London. Source: peterbarberarchitects.com

21

Fleet Street Hill, London. Source: peterbarberarchitects.com

Building Design

Policy Review

Notwithstanding the positive aspects of a context-driven design policy, this emphasis on sense of place could trigger conflicts. For instance, other environmental aspects of design are given consideration in the NDP: climate change resilience, flood protection, water storage, minimum internal floorspace, accessibility, biodiversity and solar collection, for instance. But these are sometimes incompatible with local character, as when the predominant building form in an area may have been driven by other factors that may have been important at the time of the building being erected, but are less relevant now.

An example of this, is roof forms. Historically, pitched roofs were the solution to the cover of buildings as these dealt well with water and snow through gravity and were relatively easy to construct with timber and clay tiles or slate, available materials back then. Nowadays, construction techniques have evolved and designers are aware of thermal loss of complex and extensive external building surfaces, energy can be collected using photovoltaic panels and rainwater can also be collected form roofs. As land is scarcer, roof terraces become more attractive outdoor spaces.

A strong emphasis on contextual design is important, but drastically relying on traditional contextual building design solutions is not, in my view, an adequate route forward. I suggest considering all available solutions and factors.

Extract from the Lewes NDP

22

Car Parking and Transport

Policy Review

The NDP seeks to improve the environment around the station for pedestrians, which is very poor at the moment, as railway users’ access/egress the station at lower level into a car park with no safe, comfortable and legible spaces and routes. Concurrently, the NDP suggests bringing the taxi rank to the lower car park, but this would only lead to increased regular vehicular traffic on narrow routes shared with pedestrians and cyclists which are already in a poor condition and present safety challenges. The junction of Station Road and Pinwell Road is particularly unsafe due to sharp turning angles and narrow width of the road.

On one hand, the NDP suggests rationalising car parks in town, which is consistent with the critical position of this masterwork and provides opportunities for a new urban design intervention that makes a more efficient use of land and puts people at the centre. On the other hand, this policy of rationalisation is somewhat inconsistent with the NDP approach to car parking on new developments.

Other aspirations for improving the arrival space at the lower station access as well as alternative transport methods are agreed and form a structural factor in the design decision making of this masterwork.

Extract from the Lewes NDP 23

Precedent

Vauban is a mixed-use development in Freiburg which has successfully dealt with transportation, giving priority to public and active transport options. The district is structured around a tramway and several cycle lanes, followed by a grid of pedestrian routes, only punctured by occasional routes where vehicles are allowed to access but there is no traffic through. A multi storey car park serves the district, allowing the small amount of car users to park without occupying the public realm.

The key to the success was in the primacy of the public and active transport modes in the layout design as well as in allowing vehicular access whilst not designing spaces for vehicles, but for people and wildlife instead. This way, users adopted a sustainable transport approach, whilst they were not impeded to benefit from car use when needed.

24

Vauban, Freiburg. Left: Main rail + cycle route. Right: people friendly street. Source: Own

CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS

Lewes Neighbourhood Development Plan

Context Through Kevin Lynch’s Eyes

Design Principles Beyond ‘The Image of the City’

25

Methodology

I have conducted this masterwork benefiting from a solid understanding of the planning context and Lewes as I have developed professionally in the area.

The methodology is based on a critical analysis of the most relevant and locallymade planning policy (Lewes Neighbourhood Development Plan) as well as the work of authors in the field of urbanism and design that I find inspirational and compatible with my critical position. I also decided to illustrate through precedents the ideas that result from the policy critical review as these would help to visualise some conceptual ideas that will influence scenarios.

Lessons learned from policy and academic discussions are used to contextualise a site analysis of the Station Car Park. Whilst there are many aspects of the site that had to be analysed, I decided to focus on the main factors that relate to policy and academic discussions.

The method for design solutions has been based in creative sketching ideas that test the position of buildings, routes and spaces in relation to the lessons learned and design principles that result from the site and academic analysis. This is an iterative process of ideas that are successful to some regard and fail in other aspects. Each subsequent sketch builds on the lessons learned from the previous sketch.

Finally, I have developed three scenarios that are supported with site plans and three-dimensional visualisations of the proposals that identify how and where scenarios meet design aspirations in the context of the critical position, policy, academic and context analysis.

26

Illustration of Masterwork Brief MAAUD 2023 course. Photograph: Joseph Cornell Portrait. Source: University of Brighton.

Green and Blue Infrastructure

The site barely contributes to the green and blue infrastructure network due to the limited vegetation and water on site. A functional green infrastructure network requires connectivity, joined-up areas of rich and diverse habitats that contribute towards natural processes, including wildlife and water management. Unfortunately, the site is a 100% asphalt gap in between Southover Gardens and other green spaces to the west and the Railway Land flood plain to the east. The Winterbourne is a stream that runs along the bottom of the valley from west to east, but it is canalised under the railway and station car park, so there is no appreciation of the stream.

Given the existing topography and the close distance to the River Ouse, the area falls within an area of flood risk (mostly in zone 2 - medium risk). The 2000 floods illustrated well the extent of this risk.

• The site has the opportunity to connect habitats and enhance the existing stream corridor.

• Flood risk will limit the uses that planning policy support at ground level, and habitable spaces should remain at upper level.

TAKEAWAYS

Southover Gardens

Extent of flood risk

Winterbourne

Railway Land Station

Photograph of the Lewes Station during the 2000s floods. Source: The Guardian, Chris Ison/PA.

TAKEAWAYS

Southover Gardens

Extent of flood risk

Winterbourne

Railway Land Station

Photograph of the Lewes Station during the 2000s floods. Source: The Guardian, Chris Ison/PA.

27

Views and Building Heights

There is a combination of views and vistas to and from the site that are relevant. The NDP emphasises on the importance of views, in particular of the Downs and cliffs beyond, to the identity of Lewes.

I have outlined they most relevant immediate views around the site (pink) and those that offer an appreciation of the wider landscape beyond Lewes, which are more limited, but not less important.

There is variety of views available, from kinetic to static, some are constant and others brief. There are also seasonal variations as vegetation evolves, obstructing, framing and redefining views through time. There are also some attractive deflected and split deflected views in Lewes when walking revealing destinations. The viewing experience in Lewes is diverse and it is part of what makes the town special.

TAKEAWAYS

• Views of landmarks and the wider landscape are an essential element of the identity of Lewes and any intervention should respond to these as much as possible.

• Routes are key not just in allowing views through the absence of built form, but also, through layout, in providing a variety of viewing experience, e.g. sequential and deflected views. This diversity of views should be an aspiration for new development.

V1

V1. Downs from railway bridge

V2

V3

V4 V1 V2

V3 V4

Three

Four

Single storey Two storeys

storeys

storeys or more

V2. Lewes Castle from Station Road

V3. Station from upper Station Road

28

V4. Depot Cinema from Station lower access

Access

The site is accessed by vehicles, cycles and pedestrians mainly from the Southover Road - Station Road junction, which is an unsafe point of access, not legible for people travelling from the south and not in an adequate angle for safe vehicle access and egress. The pavement is on occasions encroached by vehicles too. Alternative access for vehicles is available via Pinwell Road, but is used less frequently. A public footpath connects the eastern end of the site with a 20th Century residential development to the east, the countryside, and the college across the railway. There is no direct access to the western end of the site, which can only be accessed from below Station Bridge.

The station benefits from an existing taxi rank and drop-off area at the front and main access, outside of the red line area.

TAKEAWAYS

• Pedestrian movement should be prioritised and desire lines be incorporated in the layout.

• Consideration should be given to movement through the site from east to west.

• The Southover Road - Station Road junction and vehicular access to the site is not safe and action should be taken to improve vehicular and pedestrian safety.

• The mix of uses reduce the need for vehicular transportation where uses and activities are in close distance, therefore there is an opportunity to reduce parking provision.

• Network Rail may need occasional access to the railway from a road, for maintenance and emergencies, which should be accommodated, ideally from the south side of the railway.

Land Use and Ownership

There is a mix of uses that support a balanced live, work and enjoy range of daily activities in the area. The town is also well-served with community facilities within walking and cycling distance. Therefore, this part of town is very much lived in the spirit of a ‘15 minutes city’ and the site offers an enormous opportunity to further complement these uses with a mix of spaces that build further this environment.

The site is owned by Network Rail, which could facilitate the design, negotiation and delivery of a development in contrast to sites with multiple land owners.

Civic building Education Residential Employment Retail and leisure Uses Vehicular routes Pedestrian routes Railway Movement SouthoverRd.

30

Station Rd. PinwellRd.

Parking

The Station Car Park comprises 284 parking spaces, of which 270 are regular car parking spaces, 8 are for short stays and 6 for disabled. It also counts with 4 spaces for motorcycles and 100 spaces for cycles. The Depot also has 2 disabled spaces.

The Station Car Park is occupied, on average, only between 25-50% of its capacity.

There are a number of public car parks in the vicinity, on a reasonable distance by foot, and at least two large private car parks serving Lewes Jobcentre and the East Sussex College south of the railway. Considering the variations in working patterns since the Covid-19 pandemic, with less staff attending their workplace in a daily basis and more remote working and studying patterns, I would challenge the actual existence of the Station Car Park.

Given the proximity of public and private car parks in the station area, I recommend the following:

• Survey the use and capacity of these car parks and identify the actual need of parking spaces for railway users only.

• Create partnerships between local bodies and Network Rail with others (Jobcentre and East Sussex Collage) to share existing car parks with other users, maximising their sustainability and an efficient use of land.

• Promote, through the removal of parking spaces, a change in transportation behaviour from carsolutions to active and public transport modes.

The above should give enough grounds to significantly reduce or omit the existing car park, which currently used on a small proportion. If there are public and private car parks in town that are not used on their full capacity, shouldn’t a solution be proposed to rationalise these and make an efficient use of land as well as encouraging sustainable transport?

TAKEAWAYS

• Understand the actual parking need of the station and find alternative reduced parking provision within existing car parks in the area.

• Omit the Station Car Park, leaving only cycle and disabled spaces.

Public car park + parking spaces Private car park + parking spaces 2 min. Approximate walking distance

31

Conservation Area

Air Quality Management Area

Scheduled Monument

Land allocated for residential development

Lewes Neighbourhood Development Plan

The NDP has some significant spatial implications that has shown on the map. I find many of these very inspirational and forward thinking, sometimes expanding the reach of the planning system from a land use control to a town management tool.

The Station Car Park site is a focus of traffic in the centre of Lewes. Therefore, I find that there are efforts in the NDP towards traffic reduction, creating better streets and cleaner routes for people and wildlife, but, if fact, changes could be only cosmetic if no attention is given to the sources of traffic and its environmental impacts.

The car park site represents a land use working against many NDP aspirations. Therefore, one of the tools to facilitate this aspiration of the NDP would be to challenge the uses that represent a threat towards the NDP’s implementation. I therefore propose to question whether the car park should remain there, either in its current size or whether it should be retained at all.

Considering that cars cause visual negative impacts, their removal from this area could represent an improvement to the experience of place and in particular to calming nearby streets. It would also give space back to wildlife and people in a safe environment, and less cluttered environment for the enjoyment of the heritage trail and all cultural assets in the area (Conservation Area and Scheduled Monuments too).

The Heritage Trail is expected to provide an immerse experience into the historic sense of place of Lewes, but a car dominated environment would only detract from it by reason of the presence of outof-time and unsightly vehicles, as well as an enjoyable and safe environment for all.

I would criticise that the NDP aspires to the improvement of its pedestrian routes, but it fails to spatially identify, in this area in particular, any area for improvement or potential strategic solutions. The site in question is not characterised for its permeability, especially on its western section.

There is, however, a great opportunity to enhance the quality of place along the proposed Green Links. These are routes that could help to connect, with nature, the countryside beyond to the town, but some of the areas, especially on the eastern end of the site, are not legible nor inclusive.

Heritage Trail Green Link

Traffic Calmed Street

Local Green Space

32

Landmarks

Context through Kevin Lynch’s eyes

There is a hierarchy of landmarks in the area. The most immediate landmark is Lewes Station, but there are other structures that whilst may not be seen as a primary landmark, are relevant locally: The Station Bridge and the Depot Cinema. A town-important landmark is Lewes Castle, from which panoramic views of the town and wider landscape can be enjoyed, and which can be seen from many vantage points. Whilst the castle functions as a town important landmark, it is less relevant in the site’s location, as the Depot Cinema and the Station become more prominent to observers and are clear contrasting elements of this space, making the location of the site more easily identifiable than the castle.

Nodes

Nodes are not easy to identify at this scale, but there are some points in the locality that could be considered quasi-nodes of a small scale. In these spots, the observer accesses a junction of activity, people, a focal point, an overall thematic concentration.

The main node is the railway station itself and its approaches, as well as it connects to a principal route in the area: Station Road. Another node would be junction of Station Road, Southover Road and Landsdown Place, an important vehicular and pedestrian meeting point immediately north of the site.

Routes

Routes or paths in Lewes play a significant role in the environmental perception of Lewes. These channels in which observers move, support an understanding of the town’s structure, from High Street to district’s main streets, from higher to lower ground, commercial and residential uses, distinctive character of districts, they also create, reinforce and reveal landmarks in a diversity of ways.

When visiting the site, one clearly identifies some of Lynch’s urban elements. For instance, as one approaches the site, travel takes place through a route. There are a number of perimetrical routes that abut the site, an important route that cuts it across into two and then a network of informal, changing and confusing desire lines throughout most of the site.

All routes from north to south are characterised for being relatively narrow, only one serving vehicle traffic through, with buildings immediate adjacent, and above all, steep topography. Buildings along the route are usually between 2 and 3 storeys and step down with the natural landform. Routes, through their design and the buildings and gaps around, are the most powerful element in the area to order the set of urban elements.

Edges

There is also a clear edge to the area formed by the railway line and the Railway Land to the east, as there is a physical boundary that forms two distinctive areas on both sides. Whilst not impenetrable, the continuity of the railway as well as the visibility of a district different in character beyond, define the railway as a linear edge in town.

Districts Defining districts is a more difficult task to do, as the area in question could be considered an anomaly, a gap in the urban theme. Southover is the most immediate neighbourhood to the west, mostly residential. The area to the north has a closest relationship with the High Street and the core of the town and has mixed commercial and residential theme, whilst the eastern areas are mostly formed by 20th century residential suburban development that lacks any connection to Lewes.

Kevin Lynch’s application of districts requires significant research in practice. Therefore, in order to save time and rely on solid evidence, I consulted the Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan (CAAMP) of Lewes, which is being produced by the SDNPA at the moment.

The CAAMP splits the Conservation Area into character areas based on what makes these areas physically distinctive from other. Based on the character assessments, I have identified three main districts aqround the site, none of which encroaches into the site, as the site feels clearly as a gap in town, not capable of being identified as part of it, or any of its thematic areas.

District Node Edge Route Landmark *

33

Castle

Depot Station

Landsdown Place

Interconnection of urban elements

An important factor is the way in which these elements are interconnected and structure the area. Routes suggest views of landmarks and edges. For instance, numerous routes evidence the presence of edges by creating steep vegetated walls, or boundary trees. Many routes also reveal vantage points in the way they are designed in terms of orientation, curvature, openings and built form and scale. A great example of this is the almost constant view of the top of the Downs or the white chalk cliffs from many vantage points on many routes. When these routes curve, the vantage point varies offering a kinetic view of the landscape beyond, but the

landscape background remains constant. This pattern can also be found with Lewes Castle, which benefits from being at the highest point in town, but the urban fabric below the castle allows in many cases a visual connection to it from edges, nodes and routes. Even more interesting is the visual communication between several landmarks. In Lewes, the castle is not just visible from random points, but it is visible from other landmarks like the station, as the station is visible from the castle, from the Depot, from the Downs... This interconnection between urban elements would be a useful tool in new designs.

Southover is a distinctive district in Lewes.

The main entrance of Lewes Station is a local node.

The railway divides the town into distinctive districts and defines their edges.

Lansdown Place is a route that offers sequential and deflected views along.

The Depot Cinema has become a landmark, as singular building and activity focal point in town.

Southover is a distinctive district in Lewes.

The main entrance of Lewes Station is a local node.

The railway divides the town into distinctive districts and defines their edges.

Lansdown Place is a route that offers sequential and deflected views along.

The Depot Cinema has become a landmark, as singular building and activity focal point in town.

34

Illustration suggesting connections between elements of the image of the city. Source: Own.

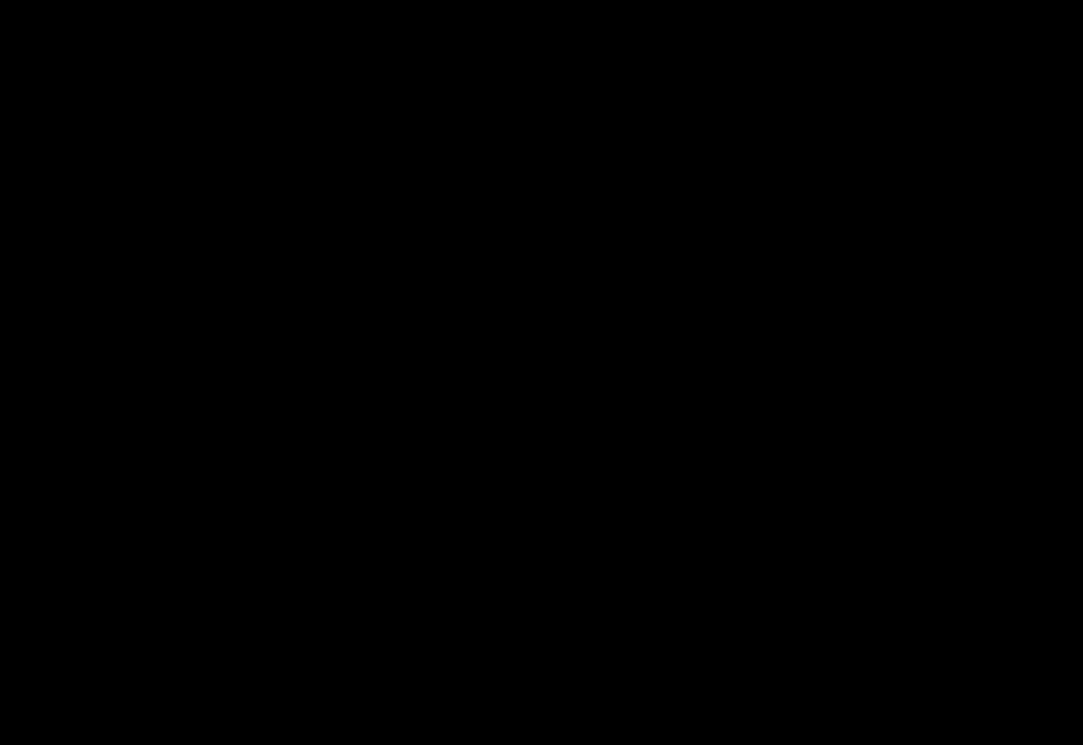

Design Principles Beyond ‘The Image of the City’

Now that the image of this area of Lewes and its interconnected elements are understood, I outline design principles that respond to the lessons learned from Kevin Lynch:

Routes should emphasise a sensorial significance through superposition of elements, perspectives, focused views of landmarks. They should also help to visualise the distance and topographical changes of space from a distance to ensure that users are conscious of movement and effort.

Sensorial experience could go beyond vision, and incorporate the sound of water, surface textures, etc.

Stimulate new exploration through routes, indicating, through form, a differentiation of direction and destination. For instance, routes could suggest whether they direct users towards the town centre, the station or the countryside.

Routes towards the town could be surrounded by built form, suggesting town themes, and routes towards the countryside/ open space could be partly vegetated, hinting a route towards a natural environment.

Reinforce existing edges between districts. A linear element along this edge would facilitate this differentiation of spaces. Ideally, it should retain visual contact of the district across the edge as well as to incorporate some permeability.

The south boundary could strengthen the visual edge and separation of districts on both sides of the railway. The Winterbourne and vegetation along the way would stress this linearity. Build form, could also help reinforcing a volumetric edge.

The hierarchy of all elements should be evident in either size, intensity or interest. Simple forms that should also have a degree of continuity or rhythm, to thread everything in an interconnected network of things that lead to an identity.

The main landmarks should remain as such, and the secondary ones too, whilst enhancing their experience. A new landmark could result from the design, as long as it does not detract from existing.

Design layout and buildings following a borrowed homogenous theme that brings them into an adjacent district character. The district to the north is the most obvious theme.

Retain landmarks and, where possible, increase their singularity with additional contrast

Routes should order the set of urban elements.

Strengthen nodes for people that are well defined and remarkable, not capable of being confused with another place.

35

DESIGN SCENARIOS AND CONCLUSION

Scenario 1. Station Approach and New Southover Road

Scenario 2. Station Approach and Trees

Scenario 3. Station Approach and Reimagined Southover Road

36

Framework Development

This section explores the evolution of spatial, volumetric, movement and perceptual ideas and solutions for this site and their implications in the town, from a sense of place and quality of life perspective.

The draft framework identifies the main desire lines, destination buildings/landmarks, the Winterbourne stream and vegetation that informs the concept design phase.

37

Initial framework for the site. Source: Own.

The initial sketch was discarded early as the concept went too far too quickly in defining developable areas, blocks and heights of buildings, before analysing all evidence available and agreeing a hierarchy of design principles. For instance, many views were identified, but no hierarchy was established on which ones were more valuable than others, therefore the concept layout was almost impossible and not practical given that it was driven mostly by views and there was no scope for other elements to define the concept.

This first version did incorporate elements that are carried throughout the evolution of the concept:

• Bringing the Winterbourne Stream to surface and connect green infrastructure along the corridor.

• Create a transition from the Depot Cinema open space and the station.

• Use and activate the existing arches under the station bridge as part of the development.

Iteration of Concept Plans

Subsequent concepts aimed to reinforce the key elements from Kevin Lynch’s assessment. Therefore, the railway edge was strengthened by bringing the Winterbourne Stream back to surface. It was also decided that the settlement pattern should respond more to the area north of the railway as there is the opportunity to extend districts or themes into the site. Important views of the landmarks and wider chalk cliffs and Downs also started defining spaces, but some of the buildings obstructed these views. The north to south permeability was prioritised while east to west movement was yet undefined.

While the stream, permeability and Station view corridors were key factors, there was no holistic concept for the whole site and some viewpoints were not yet well-responded through design (see V7).

An opportunity to improve the main node (Southover Rd.-Station Rd.) was seen on completing it with prominent landmark corner buildings.

38

Approximate building and flat dimensions

The subsequent concept plan evolves envisaging the realistic capacity of the site and the typology of buildings and routes. A perimeter block is proposed as the solution for the eastern part of the site. This intervention creates an attractive pedestrian route along the south edge, transitions along the edge from the suburban development to the east towards the public space opposite the railway station, whilst keeping visual references of the station from a number of vantage points within site.

The row of trees was decided to be retained and integrated it in this layout. This has led to some difficulties in integrating them (on 4.5 metres high bank) into the layout. The concern is

Southover Road, bank and building section

that the space between the road and buildings (trees + bank) would be a leftover space with no activity, natural surveillance and a potential focus of damp, rubbish and undesired activities with no overlooking. This is a concern yet unresolved.

The western blocks are envisaged as group of buildings that read as continuous street scene from the bridge and Southover Road, and its curved extension to the south, creating a yard or semi-private open space. The benefit of this approach is that it creates a hierarchy of open spaces that could be used either by residents at upper levels, by workshops are ground level as part of their working area, or both. The ‘extension’ element also benefits from a dual

aspect (public realm and internal yard), which adds add flexibility to the range of activities and uses that it could accommodate. Opposite the Depot Cinema, a single storey semi-triangular building could function as a transitional building between the iconic Depot Cinema and the perimeter block to the east. This building is conceived as a low-rise unobtrusive structure that allows views of the Downs and the roofs beyond from the west. This plot is defined by important desire lines, views and framing a public arrival space opposite the station.

The eastern perimeter block works well in urban form and scale, given the defining desire lines (movement, views and edges). The public

remains on the perimeter, where routes suggest direction of destinations and provide a variety of environments: hard and urban on the north side of the block and soft and open on the south side.

This concept remains problematic in terms of the bank (trees and building relationship), the oversized and not clearly defined public square opposite the station and lack of defined function and form for the western end of the site, where the Winterbourne enters the site. Furthermore, the curved element of the courtyard building denotes suburban themes incompatible with the character of this district.

39

Changing levels should be used on any scenario as an opportunity for creating high ceiling ground levels

The bridge’s arches and building behind could become the access to a station cycle park integrated in the new building

I explored alternatives that would not entail the loss of trees along the bank. Whilst there is an argument for their loss: creating a new street scene based on the theme of the area to the north and avoiding a poor space between building and street (bank), trees have valuable ecosystem and identity functions for nature and people. Therefore, I explored options that would respect existing trees along the bank and incorporate them into a shared open space.

The alternatives resulted in a mix of shared spaces between buildings and the bank, but reduced significantly the space and flexibility for uses and activities and some of the conflict with the bank would remain as long as there is a building in close distance. It also loses some of the reinforcement of the node at the street junctions (Southover Rd. - Station Rd.) as the corner building is reduced in prominence.

I do however believe that these alternatives have merit and that still retain the fundamental element of permeability, mix of open and internal space and scales, as well as the Winterbourne corridor along the south boundary.

The Station would require a projecting entrance over the Winterbourne and the arrival space (Station Square) starts to take shape, being now better defined by desire lines and the immediate response to the Depot Cinema garden and access.

This proposal incorporates cycle parking inside the proposed building adjacent to the bridge, so cycles remain secure, accessible and convenient. Access to it through the bridge’s arches will make it memorable.

40

Cycle parking

This latest version of the concept plan advocates for giving more weight to the sense of place and Kevin Lynch’s theory on the image of the city and its defining elements of districts and nodes.

The main variation of this revision is the removal of the tree belt along Southover Road, by siting new buildings closely along the line of the road, which would be consistent with local pattern of the district which theme is being carried into the site (north buildings directly addressing the road and building lines on the street edge or very close). Trees only within gardens or well-define open spaces.

Views of the main landmarks (Station, Castle and Depot cinema) are retained and re-framed in a new hierarchy of views and spaces. Nearby routes integrate into the site and define building blocks. Built form plays an important role in repairing and creating the grain of the town and activating spaces.

The loss of trees has been assessed carefully. Their loss should be avoided in most cases, although their location along the road and on the bank does jeopardise achieving an efficient building layout.

According to a recent arboricultural survey reviewed in the public planning registry, the majority of trees are ‘category C’, therefore of low quality of limited life expectancy or they contribute little to amenity. However, surveys only focus on the arboricultural quality of specimen, I adopted a holistic approach, which considers other functions of trees and factor them on this third concept plan.

Trees have the potential to perform many functions and maximising the benefits that they provide to people and nature is key in this urban intervention. I suggest maximising these in the long term by placing them creating corridors for wildlife, where they provide shade in summer to public realm, at a lowest ground level where they absorb water, amongst other. The life expectancy of trees is important to maximise benefits: a flat area with water availability is an adequate solution for a longer life of trees and for extending their benefits longer in time. A new corridor of trees along the Winterbourne has therefore the capacity of being more beneficial to nature and people than the existing trees. Removing trees is an unpopular decision but this scenario remains valid.

Pavillion

41

Estimated benefits (from lower to higher) of trees through their lifetime. Existing vs. proposed on the sketch concept layout on this page.

Work + live units

Work spaces ground level + flats at upper level

Scenario 1 Station Approach & New Southover Road

Scenario 1 offers a transition from the northern district into the site that blends in with the character of the area, by bringing build form along Southover Road and strengthening vistas through focal points at the end of the road as well as emphasising the node/junction of Southover and Bridge Roads. The node is also improved by surrounding it with corner buildings as well by closing the access to the site to cars, as the quarter will be car free, except from occasional delivery, emergency and disabled access.

The green corridor follows the southern edge of the site, along the railway and the on-surface Winterbourne. These are accompanied with pedestrian routes, all emphasising the edge, whilst allowing permeability and movement from the station to town and the countryside to the east.

The Station Square would be framed by buildings and a pavilion/kiosk, activating the square at ground level. The square would be framed to enable a direct relationship with and complement to the Depot Cinema open space opposite.

A variety of open spaces/courtyards enhances the outdoor range of activities and range of potential users, from private to public, and from work to habitable spaces.

The layout still allows vehicles in and out on the existing access points, whilst this is not encouraged through design, but not made impossible, if necessary.

42

25m 25m

SouthoverRoad PinwellRoad Station Road

Court Road

Scenario 1

Station Approach & New Southover Road

New buildings are accessed from the road and lower courtyard, with a mix of work units and flats above

Node enhanced through corner buildings and safer pedestrian environment

Kiosks provide useful services, allowing people to stay for longer in public spaces.

Private open spaces are shared and adapt to the needs of live + work units.

The new street borrows building lines, scale and width of buildings from the north

Structures provide a buffer protection to private spaces from railway

Scale of buildings integrated in roofscape, creating street scene and stepping down with levels.

New pedestrian square provides an arrival point to Lewes.

Block combining ground floor workshops and non-habitable spaces and accommodation on higher floors

Corner buildings help to make spaces memorable where addressing public realm

43

Scenario 2 Station Approach & Trees

Scenario 2’s main focus is the retention of all existing trees and bank along the Southover Road boundary, as these also contribute to the distinctiveness of the area, shade, biodiversity, etc. The built form to the south has been designed so trees become an important part of the open space strategy. Therefore, whilst this layout retains a range of open spaces (as Scenario 1) from more public to private in courtyard, the latter benefit from the presence of vegetation.

This option reduces the capacity of the site as buildings would have to be lower in height on the western end in order to prevent them from blocking important views of the Downs beyond from Southover bride over the railway.

Station Square and the buildings to the east also change slightly. This is to enable the Depot Cinema building to define the building line of the new structures. This helps framing a square that is not just perceived as a funnel Depot-Station, but also allows space for appreciation of the Depot Cinema as a landmark when arriving by rail, as well space for outdoor seating opposite the new blocks for a cafe or restaurant.

The eastern end of the site is common in all three scenarios and consists of a rearranged piece of public realm from a messy network of paths to a space that is framed by the footpaths (following desire lines) and the new building, whcih helps defining the space. This space is characterised by existing tree cover and provides a trnasition from the new development to the east.

44

25m 25m

SouthoverRoad

PinwellRoad

Station Road

Court Road

Scenario 2 Station Approach & Trees

Roof forms are only indicative but illustrate the potential they have in emphasising a corner

Pinwell Road is extended and split into two routes, creating deflected views of the Station and the Station Bridge.

Enclosed vegetated courtyards are better for microclimate and protect from noise and air pollution.

The Station remains as the main landmark, visible from within the site and beyond.

The edge is strengthened with native vegetation that create a soft route and access to the block, providing shade in summer and a perception of nature, including water.

45

Lower building heights allow the Station and the Downs beyond to be seen from Soutover Road

Scenario 3

Station Approach & Reimagined Southover Road

Scenario 3 proposes a mix in between the previous scenarios. The main variation is the treatment of Soutover Road, which would see its existing trees removed and buildings positioned in close distance to the road, with the benefits mentioned in scenario 1. Notwithstanding this, the space between the road and buildings would be at the road level and planted with street trees, which in the long term would create a continuous canopy and make a strong contribution to the character of the road. This way, street trees remain in the long term, but the building capacity is maximised, including the use of the lower ground levels (accessed from courtyard) for businesses and the Southover Road level for access to housing.

The western section of the site remains as per scenario 1, including the cycle store under the bridge.

The Station Square is reduced from scenario 2, to a more proportionate size, which balances views, activation of space, desire lines and compact buildings.