3 minute read

The Design Process in Planning

The planning policy applicable to this site mainly consists of the National Planning Policy Framework, the South Downs Local Plan (SDLP) and the Lewes Neighbourhood Development Plan (NDP). Whilst all are applicable, the Lewes NDP is the policy document that is most specific to the town, therefore it would be subject of analysis in detail.

Landscape-led design

Advertisement

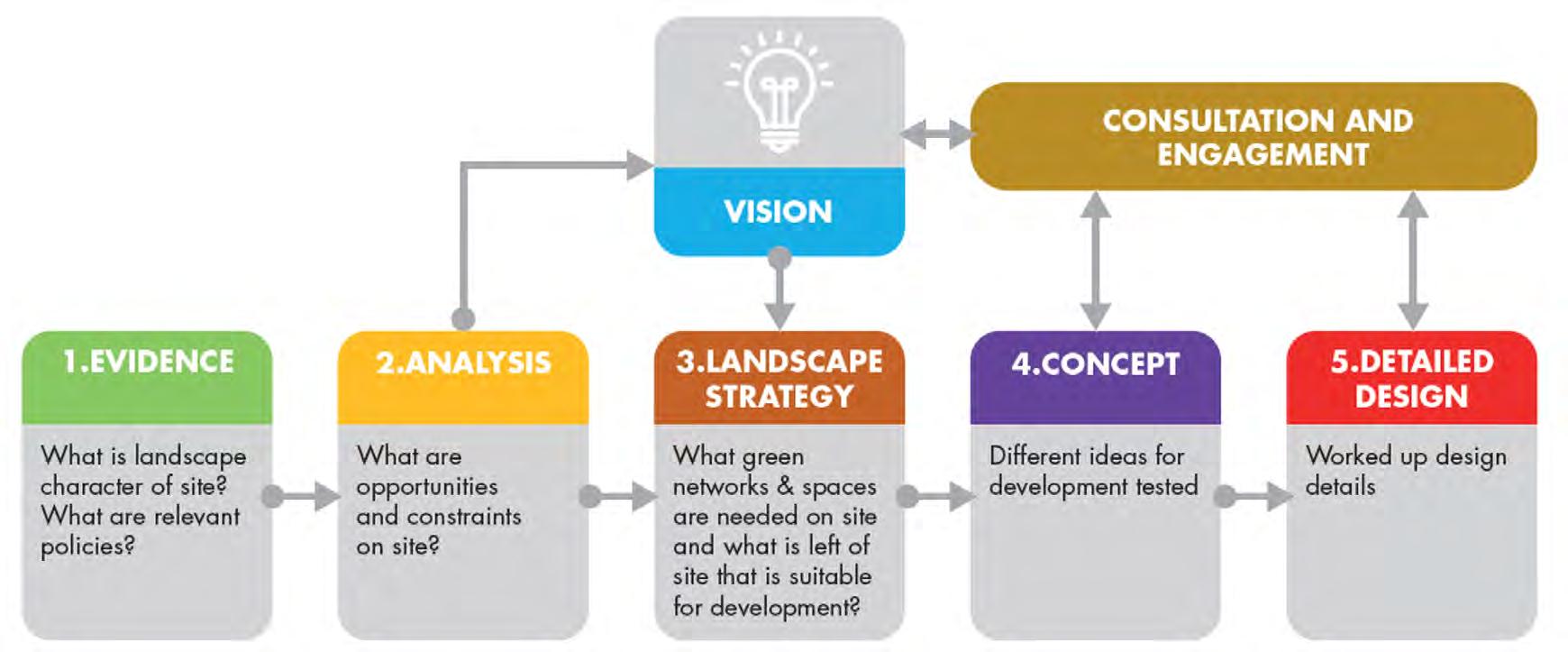

The SDLP has adopted a landscape-led approach to design, requiring design proposals to be strongly informed by an understanding of the essential character of the site and its context (the landscape), creating development that speaks of the location, responding to local character and fitting well into its environment (SDNPA, 2022). The SDLP also expects development to conserve and enhance the natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage of the area and create sustainable and successful places for people.

The above requirements are common in a contemporary set of planning policies in a protected landscape. It is however somewhat new that the planning policies set out the design process expected, guiding designers through a process that should take them to a solution that positively contribute to the National Park. Overall, the aim of this process is to strengthen sense of place, ensuring that the towns and villages of the National Park retain what is characteristic of these settlements and they not become of a diffused identity, which would erode what the distinctive towns and villages that make the National Park special.

In my view, this approach is useful, but it has an essential problem, and it is that it still does not solve the question of balancing conflicting factors and decisions in the design process. The approach to design is landscape-led, and therefore, landscape-biased. But what happens when the process results in a design that integrates well in the landscape, but fails, for instance, to promote social interaction, or incorporate passive house principles? What happens when the landscape evidence (based on the existing built environment) becomes an obstacle in a forward-thinking complex design process?

I can think of scattered detached houses being the traditional settlement pattern of a place, which the landscape-led approach would “require to replicate” if following the process literally. However, in contemporary urban design and planning, this approach would be challenged as an inefficient use of land. One could also say that detached housing contributes to segregation of communities, poor social sustainability and problems of affordability. Therefore, when should the landscape-led approach to design start and when should it end to ensure that settlements integrate with the existing landscape, but also contribute to making better places for people?

Neighbourhood Development Plan

The Neighbourhood Development Plan vision for Lewes follows the same approach, but emphasising the role of businesses and arts as part of the cultural heritage of the town. This evolution of the NDP landscape and design policies derive from the source of Lewes’s quality of place and living, resulting from the years by creative working industries, a radical and independent identity and a connection to its geography. Similarly, when tackling climate change adaptation, the NDP vision for Lewes embraces resilience and imagination, aspects related to the historic and present creative and working environment of the town. Interestingly, the vision also puts people first, when stating that people’s quality of living should be the most important matter in new development. This is ambitious in a policy document, where others in comparison do not mention in such emphasis ‘people first’.

It is however unfortunate that no policy covers well health and wellbeing as required outcomes of good urban design. They are only seen from an ‘access to the countryside’ approach, but not a design principle that should influence living and working places. However, I would challenge this approach in two ways:

• Work areas, not only residential, should benefit from access to open natural spaces, as people spend the majority of the day in their workplace.

• Access to the countryside is no the only way to deliver benefits to health and wellbeing. Internal and external spaces are equally important and they complement each other depending on weather. But more importantly, the way of living resulting from the development would be the most crucial factor when determining the quality of health and well-being. Having an active life of walking, cycling, socialising, etc. could be delivered through design, but planning policies barely focus on these.

These policy documents are rural-biased: the benefits of open spaces are not seen from an urban standpoint, but from a suburban and rural viewpoint. This could be understood given the rural nature of the National Park, but in some towns, such as in Lewes, policy has to be interpreted to ensure that health and wellbeing are factors considered in the design process. In this instance, the NDP better understands urban peculiarities of space and better deal with solutions than the Local Plan, when supporting innovative higher-density housing, and even suggests roof gardens as a solution. Notwithstanding this, there are numerous matters that require attention and are covered in this chapter.