Martin Pelenur Sistemas

Martin Pelenur es un incansable experimentador. En estos quince años desde que lo conozco he visto fuertes cambios en su obra, desde las grandes telas negras donde la luz rebotaba en la oscuridad hasta otras conformadas por cintas donde la geometría prevalece.

A veces veo sus telas sin enmarcar y sin bastidor y esas obras me hacen pensar en las pieles de animales; tal vez hayan tenido otra vida y el color las haya marcado para siempre…

Picasso decía «Yo no busco, yo encuentro», y quizás el camino del artista sea encontrar, pero para encontrar hay que saber buscar.

Martin busca, busca siempre, y es posible que busque la libertad, la libertad que le da el encuentro con el océano y la libertad que encuentra en la tela, en un mundo entre la forma y el color.

Esta exposición de Pelenur en el maca nos hace ver el punto de madurez al que ha llegado uno de nuestros grandes creadores.

Martin Pelenur is a tireless experimenter. In the fifteen years I have known him, I have seen major changes in his work, from the large black canvases where the light bounced off in the dark to the pieces made with strips of tape where geometry prevails.

Sometimes, I see his unframed canvases unmounted from their stretchers and, to me, they resemble animal skins; perhaps they used to lead a different life and color has left a permanent mark on them…

Picasso said, “I do not seek, I find,” and perhaps artists are meant to find, but to do so they must learn to seek.

Martin is seeking, always seeking, possibly freedom, a freedom that awaits him in the ocean or the canvas, in a world halfway between shapes and colors.

This exhibition of Pelenur’s works held at maca showcases the level of maturity one of our finest creators has achieved.

pablo atchugarryResulta muy gratificante para el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Atchugarry (maca) recibir al artista Martin Pelenur y su exposición Línea Merín.

Pelenur forma parte de un grupo de artistas cercanos a nuestra institución, creadores que viven y producen en nuestra zona y han enriquecido el escenario creativo del territorio donde se asienta nuestro museo.

En estos años ha expuesto en las salas de la Fundación en muestras individuales y colectivas, y ha sido siempre un colaborador entusiasta de muchos de nuestros proyectos.

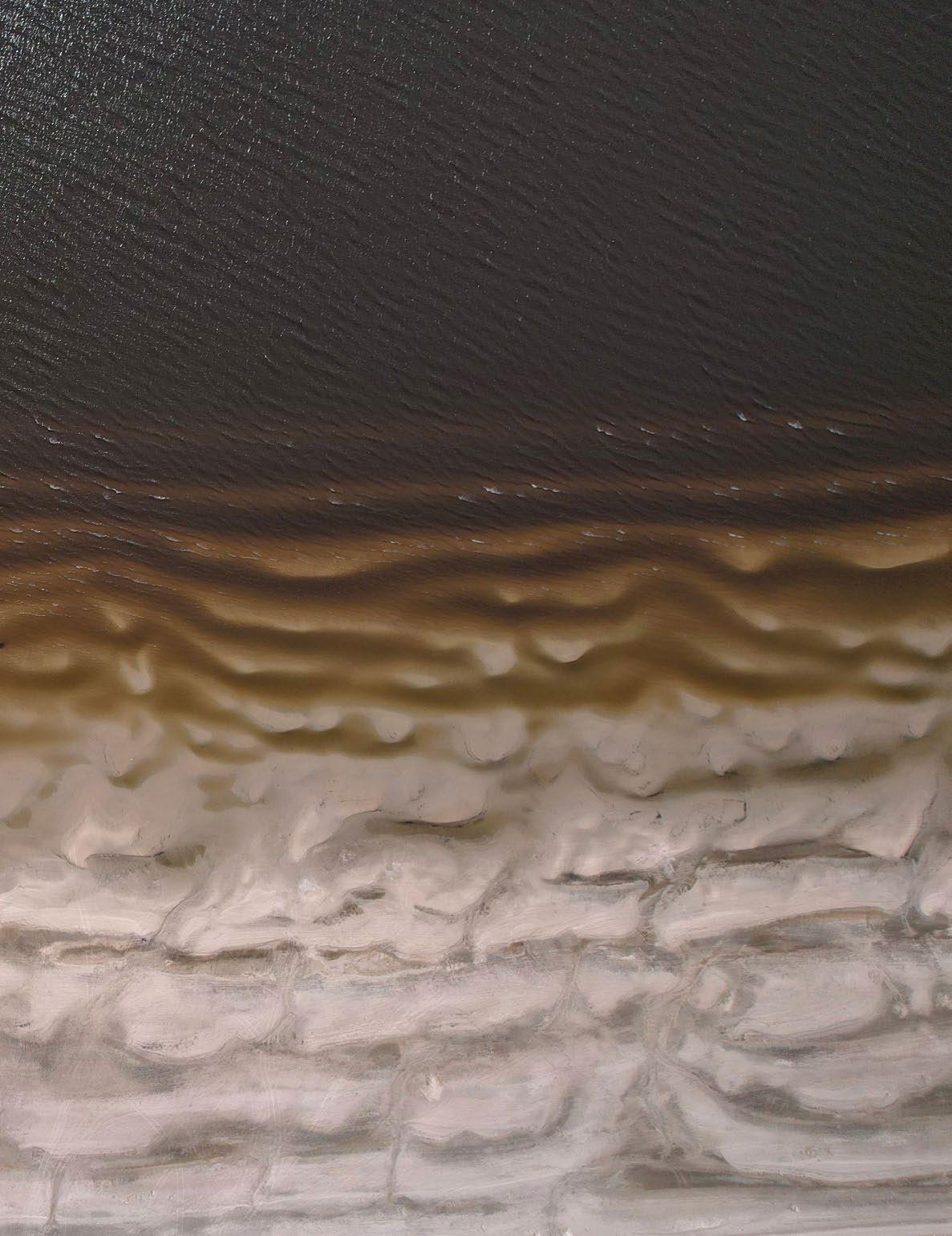

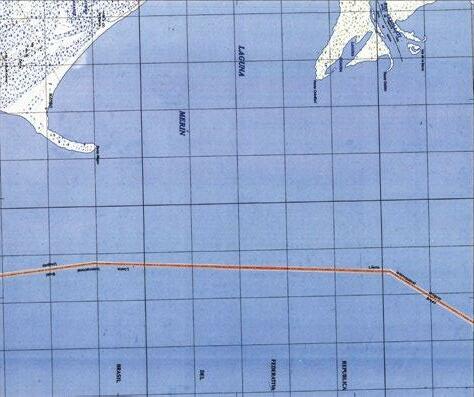

La exposición Línea Merín, curada por Martín Craciun, traza un recorrido creativo inspirado en la línea que demarca un sector de la frontera entre Uruguay y Brasil. La representación estética aquí expuesta se constituye a partir del territorio y su cartografía. Es la vivencia de campos sensibles, referidos a la contemplación del paisaje natural y su representación.

En la exposición figura un conjunto de obras realizadas en 2022. Pelenur ahonda en su obsesión por la experimentación y sus repertorios pictóricos, desde composiciones acuosas hasta la abstracción geométrica, acompañadas por proyecciones audiovisuales de su recorrido en bote por la laguna Merín y una impactante instalación metálica con seis mil litros de agua. Una plataforma de observación donde el agua, elemento vital y símbolo del ecosistema Merín, devuelve imágenes nuevas e invita a sumergirse aún más en el espacio y la experiencia que el artista pretende transmitir.

En el maca estamos abocados a la promoción y el estímulo de la cultura, el pensamiento y también la educación en la sensibilidad. Esta muestra supone una ex-

It is very gratifying for the Atchugarry Museum of Contemporary Art ( maca) to hold artist Martin Pelenur’s exhibition Línea Merín.

Pelenur is part of a group of artists close to our institution, creators who live and produce art in our area and have enriched the creative scene of the territory where our museum is based.

Over the years, he has exhibited his work in the Foundation’s galleries as part of individual and collective art shows and has always been an enthusiastic collaborator of many of our projects.

The exhibition Línea Merín, curated by Martín Craciun, comprises a creative journey inspired by the line that demarcates a stretch of the border between Uruguay and Brazil. The aesthetic representation in display stems from the territory and its cartography. It translates the experience of sensible fields, referred to the contemplation of natural landscapes and its representation.

The exhibition features several pieces created in 2022. Pelenur delves deeper into his obsession with experimentation and his painting repertoire, from watery compositions to geometric abstraction, together with audiovisual projections of the boat trip across Lagoon Merín and an impressive metallic installation holding six thousand liters of water. An observation platform where water, a vital element symbolic of the Merín’s ecosystem, reflects new images and invites visitors to submerge further into the space and experience the artist intends to convey.

At maca, we are committed to promoting and fostering culture and ideas and to educating sensibilities. This art show entails

ploración entre arte y territorio, introduce al visitante en una atmósfera cognitiva y emocional, es una invitación a reflexionar sobre la realidad del mundo, la sostenibilidad, el arte y la belleza.

leonardo noguez Director artísticoan exploration of art and territory, introducing visitors to a cognitive and emotional atmosphere, in an invitation to reflect about the realities of our world, sustainability, art and beauty.

leonardo noguez Artistic DirectorAgradezco a quienes han acompañado a lo largo de estos años: Nicolás Pequera, Sergio Turco Amiel, Juan José López, Gonzalo Delgado, Martín Barea Mattos, Diego Focaccio, Gastón Figún, Fernando Tetra Vignales, Santiago Velazco, Jesus Guiraud, Foncho López Castilla, Fernando Foglino, Nacho Guani, Tali Kimelman, Ana Grucki, Mariella Bruno, Pablo Dragovetsky, Fernando López Lage, Inés Etchebarne, Alejandra von Hartz, Silvia Arrocés, Paty Fernández, Mercedes Sader, Pablo Pi, Álex Varela, Matías Pelenur, Francisco Folle, Diego Robino y Ana Lía Rovira, Gaby van Riel, Pepe Átomo Lamboglia, Capi Rodríguez, Sebastián Zorrilla, Gustavo Frías, Nico La Tía Silbert, Rafael Lejtreger, Pablo Uribe, Mariano Piñeyúra, Valeria Píriz, Marco Maggi, Nando Marchese.

Familia Atchugarry, Pablo, Silvana y Piero Santiago Aldabalde Jorge Jorgeao de León Martín Craciun Paula Mariana Orentraij Daniel Pelenur, Gabriela Pelenur, Roxana Choclin.

agradecimientos línea merín

Fernando Stevenazzi, Rafael Canales (Lago Merín), Nacho Guani, Juan José López, Manuel Berriel, Katrine Holtz, Pato Correa, Juan Pablo Imbellone y equipo maca.

lo que hay en mí, que no soy yo, y que busco.

Aquello que hay en mí, y que a veces pienso que también soy yo, y no encuentro.

Aquello que aparece porque sí, brilla un instante y luego se va por años y años.

Aquello que yo también olvido.

– Mario Levrero, fragmento del prólogo a El discurso vacío

La siguiente publicación es parte de un proyecto editorial en el cual se incluyen obras de Martin Pelenur realizadas entre 2004 y 2022 pensadas en torno a los sistemas.

A su vez se incluyen Línea Aceguá y Línea Merín como parte del proyecto Extractor Uruguay.

La conversación entre Martin Pelenur y Martín Craciun fue grabada en la ciudad de Montevideo entre septiembre de 2021 y febrero de 2022.

The following publication is part of an editorial project in which several works of Martin Pelenur between the years 20042022 have been thought around the notion of systems.

In turn Línea Aceguá and Línea Merín are included as part of the Extractor Uruguay project.

The conversation between Martin Pelenur and Martín Craciun was recorded in Montevideo between September 2021 and February 2022.

Martin Pelenur, un ser en movimiento jeffrey kastner Página 19

Líneas de deseo roxana fabius Página 25

Sistemas para pintar Página 29

Conversación Página 61

Sistemas para pensar Página 65

Conversación Página 87

Sistemas para intuir Página 91

Conversación Página 105

Pintor Pelenur Página 111

Conversación Página 141

Sistemas para gestionar Página 149

Martin Pelenur pintor magela ferrero Página 157

content

Martin Pelenur: Being in Flux jeffrey kastner Page 19

Desire lines roxana fabius Page 25

Systems to paint Page 29

Conversation Page 61

Systems to think Page 65

Conversation Page 87

Systems to sense Page 91

Conversation Page 105 Pelenur Painter Page 111 Conversation Page 141

Systems to manage Page 149

Martin Pelenur painter magela ferrero Page 157

Conversación Página 169

Línea Aceguá Página 175

Línea Merín Página 199

Línea Merín martín craciun Página 203

Mallas en el agua maría fernanda de torres Página 207

Una laguna en campos neutrales lucía rodríguez arrillaga Página 211

Martin Pelenur Página 292

Premios y becas Página 293

Selección de muestras recientes Página 294

Los autores Página 300

Conversation Page 169

Línea Aceguá Page 175

Línea Merín Page 199

Línea Merín martín craciun Page 203 Meshes on the Water maría fernanda de torres Page 207

A Lagoon in Neutral Land lucía rodríguez arrillaga Page 211

Martin Pelenur Page 292

Awards and Scholarships Page 293

Selection of recent exhibitions Page 294

The authors Page 300

Martin Pelenur, un ser en movimiento jeffrey kastnerEn mi habitación, el mundo está más allá de mi entendimiento; pero cuando camino veo que consiste en tres o cuatro colinas y una nube. – Wallace Stevens, «Of the Surface of Things»1

Conocí a Pelenur en Nueva York durante el verano de 2021. La Fundación nars, en Brooklyn, me había invitado a conocer a algunos de los artistas residentes, y la tarde comenzó con la presentación de los miembros del grupo, que se habían congregado en torno a una mesa en la oficina. El director del programa me preguntó acerca de mi trabajo como escritor y editor, y sobre mis intereses como espectador y crítico en general. Según recuerdo, le contesté sin pensarlo demasiado, explicando que había escrito sobre prácticamente todas las disciplinas artísticas, aunque no mucho sobre pintura, probablemente. Le dije que no era una cuestión de que no me interesara la pintura per se; más bien, que no siento mucha afinidad por el formalismo, por obras dedicadas más a considerar la naturaleza de su propia producción que las ideas y los asuntos externos que dan lugar a esas condiciones de producción, que es lo que habitualmente me atrae de una obra de arte. Y que, si bien esa actitud de introspección que asocio al impulso formalista puede manifestarse en casi cualquier medio, mi experiencia me ha demostrado que suele darse en la pintura más que en cualquier otro lado.

1. Wallace Stevens, «Of the Surface of Things», en The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (Nueva York: Vintage, 1990), p. 57. Citado por Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking (Nueva York: Penguin, 2000), pp. 12-14.

Martin Pelenur: Being in Flux jeffrey kastner

In my room, the world is beyond my understanding; / But when I walk I see that it consists of three or four hills and a cloud.

—Wallace Stevens, “Of the Surface of Things”1

I first met Martin Pelenur in New York in the summer of 2021. I’d been invited to the nars Foundation in Brooklyn to meet with some of the artists in residence there, and the afternoon started with introductions among the group, which had gathered around a table in the office. The program director asked me about my practice as a writer and editor, and my general interests as a viewer and as a critic. As I recall, I responded in a fairly offhand way, explaining that I’d written about pretty much every kind of art, but probably least about painting. It wasn’t that I’m not interested in painting per se, I said, but rather that I don’t have much affinity for formalism, for work devoted more to a consideration of the nature of its own making than to the external ideas and issues that give rise to those makerly conditions, which is what typically interests me in the operation of artworks. And that while that posture of inwardness that I associate with the formalist impulse can manifest in almost any sort of media, my experience had been that it seems to happen more than anywhere else with painting.

The meeting broke up and I began my individual visits, and about half an hour lat-

1. Wallace Stevens, “Of the Surface of Things,” in The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens (New York: Vintage, 1990), p. 57. Quoted in Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust (New York: Penguin, 2000), pp.12–14.

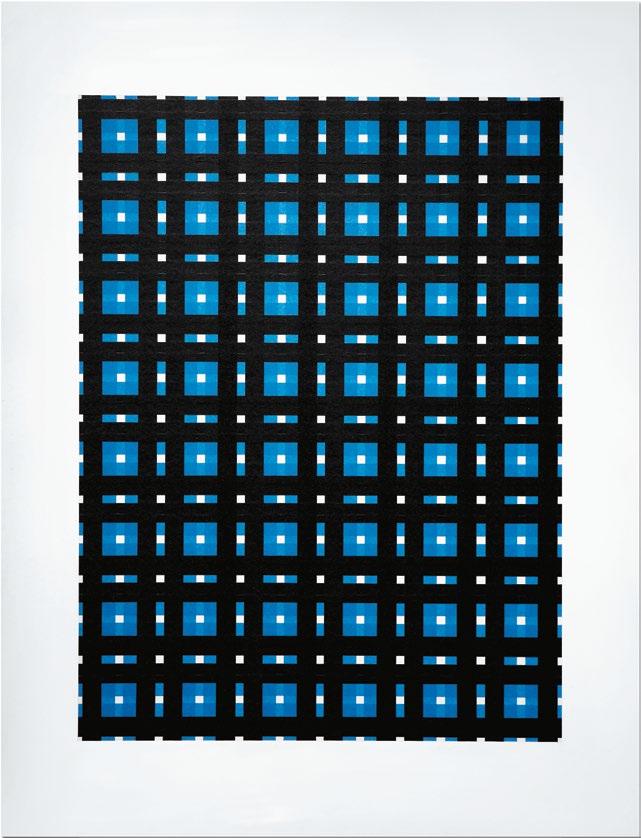

La reunión grupal concluyó y comencé mis visitas individuales, y media hora más tarde fui a dar al estudio de Martin, que me recibió con una sutil sonrisa de cansancio en el rostro. Él resultaría ser el único pintor dentro del grupo de artistas con quien me reuniría ese día y, como era esperable, había tomado mis comentarios preliminares como una señal de que no tendríamos demasiado acerca de qué conversar. Sin embargo, me mostró el trabajo que venía desarrollando en la residencia; en ese momento, según recuerdo, constaba sobre todo de cuadrículas creadas a partir de trozos de cinta negra o azul que sugerían que le interesaban los patrones, hábitos y sistemas, que luego percibiría como algo relacionado de forma estrecha con los grandes temas de su obra. Sí que conversamos, en ese momento y durante los meses subsiguientes, lo que me permitió conocer un poco más de su vida en Uruguay, su amor por el surf, y el modo en que su obra estaba signada de forma crucial por su fascinación por la topografía, el terreno, los paisajes naturales, todos elementos sobre los que yo había escrito mucho a lo largo de los años. A medida que llegamos a conocernos un poco mejor, se tornó claro que, si bien Martin es primera y principalmente un pintor, tarea que acomete con fervor (enseguida noté que su dirección de correo electrónico empezaba por pintorpelenur@), su quehacer artístico no está de ninguna manera disociado de ideas que trascienden los confines del lienzo. De acuerdo con la descripción que hace de sí mismo, en una mordaz interpretación de su obra que incluye su sitio web, él entiende a la pintura como «una forma de pensamiento […], una práctica experimental», en la que se dedi-

er I found myself in Martin’s studio, where he greeted me with a slightly weary-looking grin on this face. He was, it turned out, the only painter among the group of artists I was to meet with that day and he had – not surprisingly – taken my introductory comments as a sign that we very well might not have had all that much to talk about. But he showed me what he had been working on at the residency: at that point, as I remember, primarily gridded works using strips of black and blue tape that suggested an interest in pattern and habit and systems that I would later come to see as crucially connected to the larger themes of his work. And we did talk – then, and over the following months, as I learned a bit more about his life in Uruguay, about his love of surfing, and about how his work was grounded in some quite essential ways in his fascination with topography, with territory, with the natural landscape; all things I had written quite a lot about over the years. As we got to know each other a little better, it became clear that while Martin is first and foremost a painter, and fervently so – I noticed early on that the emails he sent arrived from an account named pintorpelenur@ – his practice is by no means dislocated from ideas beyond the frame of the canvas. As he describes himself in a characteristically wry elaboration of his work on his website, for him painting is “a way of thinking … an experimental practice,” and one dedicated not just to “the investigation of the materials I use” but also to what he calls “mental drift.”

I like this notion of “mental drift,” and how it finds its physical manifestation in Pelenur’s art practice, part of which I would come to learn engages directly with the landscape proper. Alongside his studio prac-

ca no solo a «investigar los materiales que utilizo», sino también a lo que él denomina «deriva mental».

Me gusta esta idea de deriva mental y cómo encuentra una manifestación física en la práctica artística de Pelenur, parte de la cual, descubrí, se involucra directamente con el paisaje. Junto con su trabajo en estudio, él se embarca ocasionalmente en proyectos como Línea Aceguá, una caminata de treinta y siete kilómetros que realizó en 2017 a lo largo de la frontera entre Uruguay y Brasil, o la más reciente Línea Merín, un viaje en barco a través de la laguna que se extiende por la frontera entre ambos países. A estas acciones las denomina «extracciones», por como están diseñadas para reunir información en el terreno para luego destilarla en su estudio. Entiendo que existe un diálogo entre ellas y ciertos precursores con los que las une un tenue aire de familia: el concepto situacionista de dérive, las metodologías caminantes inauguradas por artistas como Richard Long y Hamish Fulton, y los no lugares de Robert Smithson. Guy Debord describió las dérives como tránsitos «a través de entornos variados que involucran un comportamiento lúdico-constructivo y un reconocimiento de los efectos psicogeográficos», que exigen de los individuos «renunciar a sus relaciones, trabajos y entretenimientos, y todas sus otras motivaciones para desplazarse o actuar, para dejarse llevar por el atractivo del terreno y por los encuentros que a él correspondan».2 Debord y sus colegas estaban principalmente interesados en entornos urbanos, pero, alrededor de una década más tarde, artistas como Long

2. Guy Debord, «Theory of the Dérive» [1958], en Situationist International Anthology, editado y traducido por Ken Knabb (San Francisco: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), p. 62.

tice, he also undertakes occasional journeys – like Linea Aceguá, a thirty-seven kilometer hike he made in 2017 along the border between Uruguay and Brazil, or his most recent Linea Merín, a boat journey taken across a lake straddling the border between the two countries. He calls these actions “extractions,” for the way they are designed to gather information on the ground that he will later distill into his studio practice, and I’ve been thinking about them in dialogue with some loosely related historical precedents: the Situationist concept of the dérive; the walking methodologies pioneered by artists such as Richard Long and Hamish Fulton, and the “Non-Sites” of Robert Smithson. Guy Debord described dérives as passages “through varied ambiences [that] involve playful-constructive behavior and awareness of psychogeographical effects,” ones that require individuals to “drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractiveness of the terrain and the encounters they find there.”2 Where Debord and his colleagues were primarily interested in urban ambiences, a decade or so later, artists like Long and Fulton would begin seeking out wild places away from centers of population – the latter typically turning his walks into text-based works and the former often making marks in the landscape itself along the way or, in a manner that has some obvious kinship with Pelenur’s own approach, producing sculptures for the gallery or museum that evoke either the atmosphere or sometimes the very substance of

2. Guy Debord, “Theory of the Dérive,” [1958] in Situationist International Anthology, ed. and trans. Ken Knabb (San Francisco: Bureau of Public Secrets, 2006), p. 62.

y Fulton empezarían a buscar lugares salvajes alejados de los centros poblados. Fulton plasmaba sus caminatas en obras escritas, y Long a menudo realizaba marcas en el paisaje a lo largo del recorrido o, de forma obviamente afín al método empleado por Pelenur, producía esculturas para galerías o museos que evocaban la atmósfera o, en ocasiones, la sustancia misma de la que estaban hechos los lugares por los que había transitado. Esta faceta de la obra de Long es deudora, como gran parte de lo que hoy concebimos como land art o arte de la tierra, a ideas formuladas por Robert Smithson, cuyos no lugares se atrevieron a sintetizar y transformar los lugares para explorar la distinción no solo entre presencia y ausencia, sino entre experiencia y expresión. El académico Jack Flam versa sobre estas oscilaciones en su perspicaz introducción a la recopilación de los escritos del artista:

El lugar representa al mundo, el texto sin editar con todas sus complejidades y posibilidades, vasto y remoto – evocativo, pero sin logos. El No-lugar representa la expresión concentrada de parte del lugar, que hasta cierto punto sustituye al lugar, pero que como cualquier tropo metonímico adquiere vida propia y se convierte en un lenguaje: «Es gracias a una metáfora tridimensional que un lugar puede representar a otro que no se le parece – ergo, el No-lugar», [Smithson] escribió en 1967. «Comprender este lenguaje de lugares conlleva percibir la metáfora entre el constructo sintáctico y la complejidad de las ideas, permitiendo que el primero opere como una imagen tridimensional que no se asemeja a una imagen…». El No-lugar, en cierta medida, atrae al lugar desde los márgenes geográficos, psicológicos y sociales hasta el «centro» – ya sea el estudio de un

the places through which he’s traveled. This aspect of Long’s work is itself indebted, like so much of what we today think of as Land Art, to ideas articulated by Robert Smithson, whose Non-Sites endeavored to recapitulate and transform the site in a way that explores the distinction not just between presence and absence, but also experience and articulation. As scholar Jack Flam writes of these oscillations in his perceptive introduction to the artist’s collected writings: The site represents the world itself, the unedited text with all of its complexities and possibilities, vast and remote – evocative but without logos. The Non-Site represents the focused articulation of part of the site which to some degree comes to stand for the site itself; but which like all metynomic tropes takes on a life of its own and becomes a form of speech: “It is by three dimensional metaphor that one site can represent another site which does not resemble it – thus The Non-Site,” [Smithson] wrote in 1967. “To understand this language of sites is to appreciate the metaphor between the syntactical construct and the complex of ideas, letting the former function as a three dimensional picture which doesn’t look like a picture …” The Non-Site to some degree brings the site from the geographical, psychological, and social margins to a “center” – be it the artist’s studio, an art gallery, a museum, or a page of a book.3

Like Smithson, Pelenur translates the locational specifics of his “extractions” into a kind of language that centers them in arti-

artista, una galería de arte, un museo, o la página de un libro.3

Al igual que Smithson, Pelenur traduce las especificidades geográficas de sus extracciones a un lenguaje que las vierte en forma de artefactos. Pero, mientras que los no lugares de Smithson suelen utilizar analogías concretas para establecer relaciones evocativas con las cosas a las que sustituyen (piedra o tierra), en el caso de Pelenur los rastros de un determinado sitio o experiencia pueden perfectamente ser expresados mediante esmaltes o acrílico, o en tinta, lápiz o con cintas. Su proceso de condensación y concentración, de sustitución, tiene algo de cartográfico, pero nunca es uno-auno. Los mapas pictóricos de Pelenur son difusos y oblicuos, sugestivos antes que figurativos. No son el territorio, como Alfred Korzybski planteaba, sino que son del territorio.

A menudo pienso en la pasión de Pelenur por el surf, en la relación de eso con su arte y en cómo las formas de comunión con lo líquido, tanto en una ola como sobre una paleta, implican una sustancia elemental que por naturaleza se rebela a ser controlada y sometida, y que, por el contrario, debe ser abordada en aras de una intrincada coexistencia que permita la navegación. Se produce siempre una negociación improvisada: saber leer cuándo va a romper una ola o la capacidad de absorción de un lienzo o una hoja de papel requieren una combinación de destreza e intuición. Creo que la forma en que Pelenur se acerca a ambos es, en pala-

factual form. But whereas Smithson’s NonSites typically employ material analogies to produce their evocative relationships with the things they stand in for – stone, say, or soil – for Pelenur, the traces of a given place, a given experience, might just as easily find their expression in enamel or acrylic, in ink or pencil or tape. His process of condensation and concentration, of “standing-for,” has something of the cartographic in it, but it is never one-to-one. Pelenur’s painterly maps are diffuse and glancing, suggestive rather than depictional; they are not the territory, as Alfred Korzybski had it, but they are from the territory.

I have often thought of Pelenur’s passion for surfing and its relationship to his painting, and how forms of communion with liquidity – whether in a swell or on a palette, an elemental substance that by its very nature fights against control and dominion, and so instead has to be approached in the spirit of intricate navigational coexistence – is always a kind of improvisational negotiation, how reading the breaks along a shoreline or the absorbative qualities of a piece of canvas or a sheet of paper relies on a mixture of skill and intuition. Pelenur’s approach to both seems to me, as the philosopher Gaston Bachelard puts it, the product of a “water mind-set.”4 A “being dedicated to water,” he writes – and perhaps to painting too – “is a being in flux.”5

3. Jack Flam, «Introduction: Reading Robert Smithson», en Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, editado por Jack Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), p. xviii. Flam cita un texto inédito de Smithson de 1968 titulado «A Provisional Theory of Non-Sites». Se mantiene la puntuación del original.

4.

5. Ibidem, p. 6.

,

p. 5.

bras del filósofo Gaston Bachelard, producto de una «mentalidad acuática». 4 Un «ser perteneciente al agua», escribe Bachelard (y quizás también a la pintura), «es un ser en movimiento».5

4. Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter [1942], traducido por Edith Farrell (Dallas: The Pegasus Foundation / Dallas Institute of Humanities and Culture Publications, 2006), p. 5.

5. Ibidem, p. 6.

Líneas de deseo roxana fabius

Martin Pelenur trabaja con su cuerpo. No es que sea bailarín, doble de cine, acróbata o deportista. Su obra artística y su producción intelectual están basadas en el volumen que toma en el espacio, en sus capacidades físicas, en sus pasos, en lo que está al alcance de sus manos, incluso cuando estas son constantemente desafiadas.

Hace varios años que Pelenur basa su práctica, entre otras cosas, en una metodología que llama Extractor. Con ella extrae elementos de su experiencia por medio de lectura de mapas y afines que aluden a creaciones abstractas humanas, como los límites entre países, y su modo o capacidad de operar como factores de definición en tierra. Estas visualizaciones luego son traducidas al plano de la experiencia física, que, por supuesto, siempre viene acompañada de una experiencia intelectual de la que es indivisible.

Para generar la experiencia física, Pelenur hace largas caminatas, de días de duración, en las que puede sentir con los pies, la nariz, los oídos, los ojos y todas las partes de su cuerpo cómo la abstracción está o no está presente en la tierra, cómo esas abstracciones dibujadas por humanos en el papel afectan, o no, la realidad en el terreno.

Durante el trayecto horizontal de la caminata, especialmente en una superficie llana como la uruguaya, Pelenur dibuja su paso sobre el territorio, haciendo marcas que estarán estrechamente relacionadas con las que luego realizará en su obra pictórica.

El pasaje de su cuerpo por la naturaleza es una especie de ensayo mental que posteriormente se volcará al lienzo. La ex-

Desire lines roxana fabius

Martin Pelenur works with his body. And not because he is a dancer, a stunt double, an acrobat, or an athlete. His artistic work and his intellectual production are based on the volume he takes up in space, in his physical abilities, in his footsteps, in what is within reach of his hands, even when the latter are constantly challenged.

For years, Pelenur has based his practice on, among other things, a methodology he calls Extractor. With it, he extracts elements of his experience through map reading and the like, which allude to abstract human creations, such as the boundaries between countries and the way or ability they have to act as defining factors on the ground. These visualizations are then translated to the plane of physical experience, which, of course, always entails an intellectual experience it cannot be detached from.

To generate the physical experience, Pelenur goes on long walks, lasting days at a time, during which his feet, nose, ears, eyes and the rest of his body can feel whether the abstraction is present or not on the ground, how those abstractions drawn by humans on paper impact the reality of the landscape or not.

During his horizontal walking journeys, especially across a flat terrain like Uruguay’s, Pelenur sketches his passage through the territory, leaving marks that are closely linked to those with which he will perform on his paintings.

The passage of his body through nature is a sort of mental rehearsal that will be later put down on the canvas. The experience is transferred onto the fabric in an indirect way,

periencia se traduce a la tela no de forma directa, no como imagen replicada, sino como una extensión de la misma intención. No hay una verdadera separación entre cada parte del proceso; es todo parte de uno, como existe continuidad en la línea temporal de una vida, un cuerpo, aunque haya eventos que marquen un antes y un después.

Según la escritora Rebecca Solnit, «Caminar, idealmente, es un estado en el que la mente, el cuerpo y el mundo están alineados, como si fueran tres personajes que finalmente conversan juntos, tres notas que de repente forman un acorde. Caminar nos permite estar en nuestros cuerpos y en el mundo sin que ninguno de ellos nos ocupe. Nos deja libres para pensar sin perdernos por completo en nuestros pensamientos. [...] El ritmo de la caminata genera una especie de ritmo de pensamiento, y el paso por un paisaje hace eco o estimula el paso por una serie de pensamientos. Esto crea una extraña consonancia entre lo interno y lo externo […]». 1 Es ese estado de conexión entre mente, cuerpo y mundo exterior el que Pelenur pretende brindar al observador a través de la pintura: la creación de un espacio meditativo donde la experiencia de la naturaleza no se replica, pero se transmite.

Las líneas del deseo son caminos que suelen aparecer sobre el césped, creados por la erosión causada por pasos humanos o de animales. Estos caminos usualmente representan el tramo más corto o de más fácil acceso entre un origen y un destino determinados. Pelenur nos invita a reco -

1

not as a mirror image, but as an extension of the intention itself. There is not a real distinction between each stage of the process; it’s all one thing, the same way there is continuity in the timeline of a life, a body, regardless of events that signal a before and an after.

According to writer Rebecca Solnit, “Walking, ideally, is a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord. Walking allows us to be in our bodies and in the world without being made busy by them. It leaves us free to think without being wholly lost in our thoughts. [...] The rhythm of walking generates a kind of rhythm of thinking, and the passage through a landscape echoes or stimulates the passage through a series of thoughts. This creates an odd consonance between internal and external passage”.1 It is that state of connection between mind, body, and outer world that Pelenur intends to offer the beholder through his painting: The creation of a space for meditation where the experience of nature is not replicated but still conveyed.

Desire lines are paths that appear on the grass, caused by the treading of humans or animals. Those lines usually represent the shortest or most accessible path between a given point of origin and destination. Pelenur invites us to go hiking with him and, maybe, jointly create abstract desire lines in a shared space which also contains spaces of visual silence.

In an overly mediated culture saturated with images, in which we are subjected

1. Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking (Nueva York: Penguin, 2000), p. 13.

rrer con él caminos y, quizás, crear juntos líneas abstractas de deseo en un espacio común que contiene, también, espacios de silencio visual.

En nuestra cultura saturada de imágenes, sobremediatizada, en la cual recibimos flujos constantes de información visual, la invitación a participar de esta experiencia no es solo atractiva, sino necesaria, urgente y crítica.

to constant flows of visual information, the prospect of taking part in such an experience is not only appealing but also necessary, urgent, and critical.

Sistemas para pintar

N#1 Negro, 2011 Cinta papel sobre acrílico 80 × 80 cm

Colección Alejandra von Hartz

N#1 Black, 2011 Masking tape on acrylic 31.5 × 31.5 in Alexandra von Hartz collection

N#1 Azul, 2011 Cinta papel sobre acrílico 80 × 80 cm

Colección Alejandra von Hartz

N#1 Blue, 2011 Masking tape on acrylic 31.5 × 31.5 in Alexandra von Hartz collection

Sobre, 2020 Cinta papel sobre hardboard 200 × 200 × 5 cm

Colección Santiago Aldabalde

Envelope, 2020 Masking tape on hardboard 79 × 79 × 2 in Santiago Aldabalde collection

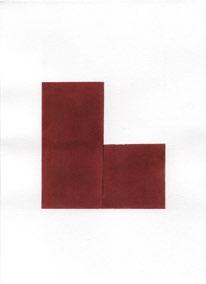

Sin título, 2018 Cinta papel sobre hardboard 100 × 80 × 5 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Untitled, 2018 Masking tape on hardboard 39 × 31.5 × 2 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

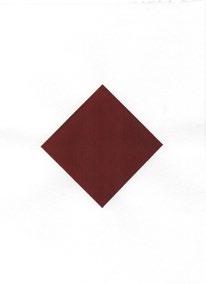

Diagonal, 2018 Cinta papel sobre hardboard 100 × 100 × 5 cm

Colección del autor

Diagonal, 2018 Masking tape on Hardboard 39 × 39 × 2 in

Artist’s collection

Sin título, 2018 Cinta papel sobre hardboard 100 × 80 × 5 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Untitled, 2018 Masking tape on hardboard 39 × 31.5 × 2 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Diagonal, 2018 Cinta papel sobre hardboard 100 × 100 × 5 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Diagonal, 2018 Masking tape on Hardboard 39 × 39 × 2 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Sin título, 2018 Cinta papel sobre hardboard 100 × 80 × 5 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Untitled, 2018 Masking tape on hardboard 39 × 31.5 × 2 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Cuadrado, 2016 Cinta papel sobre acrílico 100 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Square, 2016 Masking tape on acrylic 39 × 39 × 2 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Cuadrado, 2016 Cinta papel sobre acrílico 100 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Square, 2016 Masking tape on acrylic 39 × 39 × 2 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

página anterior Cuadrado, 2016 Cinta papel sobre acrílico 100 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

previous page

Square, 2016 Masking tape on acrylic 39 × 39 × 2 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Rectángulo, 2016 Cinta papel sobre papel Fabriano 300 g 70 × 50 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Rectangle, 2016 Masking tape on Fabriano paper 300 g 27.5 × 19.6 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Rectángulo, 2016 Cinta papel sobre papel Fabriano 300 g 70 × 50 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Rectangle, 2016 Masking tape on Fabriano paper 300 g 27.5 × 19.6 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Rectángulo, 2016 Cinta papel sobre papel Fabriano 300 g 70 × 50 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Rectangle, 2016 Masking tape on Fabriano paper 300 g 27.5 × 19.6 in Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Rectángulo, 2016 Cinta papel sobre papel Fabriano 300 g 70 × 50 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Rectangle, 2016 Masking tape on Fabriano paper 300 g 27.5 × 19.6 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Sin título, 2015 Barniz y esmalte sobre lienzo 100 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Untitled, 2015 Varnish and enamel on canvas 39 × 39 in Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Sin título, 2015 Barniz y esmalte sobre lienzo 100 × 100 cm

Colección Jorge de León

Untitled, 2015 Varnish and enamel on canvas 39 × 39 in

Jorge de León collection

3 rectángulos, 2015 Barniz y esmalte sobre lienzo 100 × 100 cm

Colección Jorge de León

3 Rectangles, 2015 Varnish and enamel on canvas 39 × 39 in

Jorge de León collection

Cruz diagonal, 2013 Barniz y esmalte sobre hardboard 20 × 20 × 5 cm

Colección del autor

Diagonal cross, 2013 Varnish and enamel on hardboard 7.9 × 7.9 × 2 in

Artist’s collection

Diagonal y mediana, 2013 Barniz y esmalte sobre hardboard 40 × 40 cm

Colección Santiago Aldabalde

Diagonal and median, 2013 Varnish and enamel on hardboard 15.7 × 15.7 × 2 in

Santiago Aldabalde collection

Diagonal (Berlín), 2012 Barniz y esmalte sobre hardboard 40 × 80 × 5 cm

Colección Safia Dickersbach

Diagonal (Berlín), 2012 Varnish and enamel on hardboard 15.7 × 31.5 × 2 in

Safia Dickersbach collection

Diagonal (Berlín), 2012 Barniz y esmalte sobre hardboard 40 × 80 × 5 cm

Colección Safia Dickersbach

Diagonal (Berlín), 2012 Varnish and enamel on hardboard 15.7 × 31.5 × 2 in

Safia Dickersbach collection

Matriz sepia, 2016 Lápiz 2B sobre papel Strathmore 300 g 21 × 14,8 cm

Colección del autor

Sepia Matrix, 2016 2B pencil on Strathmore 300 g paper 8.3 × 5.8 in

Artist’s collection

Diagramas dentro de un cuadrado de 3 × 3 pulgadas, 2016 Tinta caligráfica sepia sobre papel Strathmore 300 g 21 × 14,8 cm

Colección del autor

Diagrams inside a 3 × 3 inch square, 2016 Sepia calligraphy ink on Strathmore 300 g paper 8.3 × 5.8 in

Artist’s collection

martín craciun —Es interesante cómo llegás a trabajar con cintas. Cómo en la repetición de esas cintas desarrollás tus ideas sobre la serialización, el método, los sistemas y el proceso como premisa principal. Estas obras revelan una condición material con un resultado visual y un proceso que presenta algo del tejido o lo textil y que es vinculante con tu trabajo más químico. Lo entiendo como una manera muy radical de impulsar tu pintura hacia un lugar que te interesa —la geometría, la búsqueda de patrones y efectos visuales, los límites y sus desbordes— y que al mismo tiempo pretende expandir la idea de pintura mediante procesos. Imagino que a veces estas búsquedas sobre procesos repetitivos pueden llevarte a transformarte casi en autómata. martin pelenur —Habría que ver cómo funciona eso que decís; por un lado sí y por otro no. Autómata en cuanto al proceso repetitivo, sí; autómata en cuanto a lo irreflexivo, me parece que no. En Pintura esa búsqueda de procesos empieza con algún tipo de ejercicio sobre algo a investigar; por ejemplo, cómo se depositan los pigmentos en un soporte acuoso o, si hablamos de los barnices, cómo se genera el corrugado con un solvente.

Una vez que logro responder a esas preguntas/disparadores comienza un proceso de dominio o control de esa situación generada y, una vez controlada, arranca un método que pueda repetir. Ese sería el ejercicio en Pintura que luego se transforma en series de trabajo. No creo que haya un fin en cuanto a las series. Generalmente las discontinúo, a veces coexisten, otras veces quedan invernando por años.

mc Tengo una obra tuya, un círculo hecho en barniz craquelado que presenta unos

martín craciun —It’s interesting how you ended up working with strips of tape. The way in which, through their repetition, you develop ideas about serialization, methods, systems, and the process as your main premise. These pieces reveal a material condition with a visual outcome and a process that features elements of weaving or textiles, which links up to your more chemical artwork. I see it as a quite radical form of pushing your painting towards a place that interests you – geometry, the pursue of patterns and visual effects, boundaries, and their spillovers –, and which, at the same time, seeks to expand the idea of process-based painting. I suppose that, sometimes, these explorations on repetitive processes could turn you into an automaton, almost.

martin pelenur —We should look at the way in which what you said happens. It’s partially true, but not entirely. An automaton as far as the repetitive process is concerned, sure; but an automaton in terms of a lack of self-reflection, I don’t think so. In painting, that searching of processes starts with a kind of exercise related to something you want to explore; for instance, how pigments deposit on a watery base, or, speaking of varnishes, how a corrugated effect is obtained with a solvent.

Once I’ve managed to answer those questions/triggers, a process of mastering or controlling the ensuing situation starts, and once controlled, a method I can replicate emerges. That would be a painting exercise that eventually turns into a series of pieces. I don’t think there is an ending to those series. I generally discontinue them, sometimes they coexist, sometimes they hibernate for years.

patrones que se repiten, y otra obra que es un cuadrado neutro, azul, hecho con cintas, en el que el patrón de la cinta puede verse recién al acercarse. Quizás el ejercicio esté en cómo construir ese puente y hacer que esos trabajos coexistan dentro de la misma narrativa. En esencia, creo que tu trabajo no ha cambiado: seguís investigando sobre materiales, pintura, procesos, repetición, abstracción; pensando los límites, la geometría, los desbordes. No cambiaste el foco de atención, tus preocupaciones parecen ser las mismas. Conocés los materiales e intentás llevarlos a su límite. mp —Hay varias formas para entrarle al tema. En 2011 realicé una muestra en la galería de la querida Alejandra von Hartz en Miami, un espacio que no está más. La sala se dividía en dos: a la izquierda se encontraban los trabajos con cintas y a la derecha los corrugados, como los llamás vos. El planteo resultaba extraño porque la gente pensaba que eran dos artistas y había un solo nombre en la pared. El título era Work Premises (‘Premisas de trabajo’) y básicamente trataba sobre metodologías, cómo pintar y cómo generar patrones en una superficie determinada. La muestra fue el resultado de la investigación sobre los materiales, el cómo de las cosas, y particularmente era una propuesta sobre la superficie. ¿Cómo se genera una superficie en Pintura? ¿Cómo se genera un patrón con cintas? La respuesta surge del trabajo previo y ese trabajo viene de ejercicios perpetuos de ensayo y error en el taller. Creo que la mayoría del tiempo pasa en generar estos espacios intermedios entre la idea y la finalización de la obra; por eso la serialización y la repetición como mantras de trabajo. El concepto o noción de límite es interesante también. Pensémoslo en términos

mc I have a piece of yours, a circle made in craquelured varnish that features some repetitive patterns, and another piece which features a neutral, blue square made with strips of tape, in which the pattern can only be perceived from afar. Maybe the exercise lies in how to build that bridge and have those works of art coexist within a single narrative. In essence, I think your work hasn’t changed: You’re still exploring materials, painting, processes, repetition, abstraction; thinking about boundaries, geometry, spillovers. The focus of your attention has not shifted, your concerns do not seem to have changed. You familiarize yourself with materials and push them to their limit. mp —There are several ways of approaching the subject. In 2011, I held an art show at my dear Alejandra von Hartz’ gallery in Miami, a venue that is no longer open. The showroom was divided into two halves: on the left, my artwork made with strips of tape, and, on the right, the corrugated pieces, as you call them. This approach was strange because people thought the works on display belonged to two different artists, yet there was only one name on the wall. The title was Work Premises, and it was basically about methodologies, that is, how to paint and create patterns on a given surface. The show stemmed from the research I carried out on the materials, the procedural side of things, and, above all, it was a thesis on surfaces. How is a surface generated in painting? How do you create a pattern with strips of tape? The answer arises from the preliminary work, and that work is a result of a never-ending string of trial-and-error exercises done in my workshop.

I think that most of my time is spent generating these intermediate spaces be-

spinozianos: uno tiende al límite, ¿no? Límite como potencia; es decir, tiende al infinito. El límite de algo pensado como el límite de su acción y no como el contorno de su figura. Entonces, llevar esas ideas a los materiales los vuelve infinitos; por eso sigo volviendo a investigar sobre sus posibilidades.

mc Al verte trabajar, con los años, podría decir que la concentración y la búsqueda intensiva forman parte central de lo que hacés, algo así como una práctica basada en la insistencia, en darles vueltas y vueltas a los temas.

mp —Sí, va por ahí. Es el modo de vincularme con la práctica. Esa parte obsesiva hace que me pueda concentrar y quedar monotema hasta resolver lo que estoy investigando. Esas investigaciones tienen que ver con conocer el material desde distintos lugares. Ese conocimiento deriva de la práctica del ensayo y error. Con el corrugado de las pinturas sintéticas —porque no es un craquelado— logré identificar la reacción química y física en la superficie de la pintura, y la trabajé hasta controlarla. Una vez logrado eso, lo que hago es generar las condiciones para que suceda el evento. Ese evento es la magia y solo sucede en un momento determinado. Si uso solvente antes, se rompe la superficie; si lo hago después, nada pasa. Alquimia. En Nueva York, en la galería Sean Kelly, encontré un pintor de origen chino, Su Xiaobai, que hace lo mismo. La verdad es que me emocioné al verlo. Entonces, resumiendo: estos trabajos habitan la idea de pintura como superficie, pintura como piel. Con las cintas es distinto. La intención es generar patrones en la superficie, igual que el corrugado en la superficie de la pintura. Tal vez uno es analógico (cintas) y el otro

tween the idea and the completion of the piece. Hence, serialization and repetition as work mantras. The concept or notion of “limit” is also interesting. Let’s think about it in Spinoza’s terms: There is an inclination towards limits, isn’t there? Limits imply potential; that is to say, something leaning towards infinity. The limits of something regarded as the boundaries to its activity and not as the outline of its shape. Therefore, applying those ideas to the materials I use renders them infinite, that’s why I keep coming back to exploring their possibilities.

mc Having seen you work over the years, I would say that concentration and searching intensively are a crucial part of what you do, a sort of practice based on insisting, on turning subjects over and over in your head. mp —Yes, that’s sort of the point. It is how I approach my artistic practice. That obsessive side helps me concentrate and become monothematic until I complete my investigation. Those investigations have to do with getting to know the material from different points of view.

That knowledge stems from the practice of trial and error. Through the corrugation of synthetic paints – because it’s not a craquelure – I managed to identify the chemical and physical reaction on the surface of the paintings, and I worked on it until I succeeded in controlling it. Once I have accomplished something like that, what I do is creating the conditions for the event to happen. That event is magic, and timing is of the essence. If I apply a solvent beforehand, the surface cracks; if I do it afterwards, nothing happens. Alchemy. In New York, at the Sean Kelly gallery, I discovered a Chinese painter, Su Xiaobai, that does the same thing.

digital (pintura), aunque parezca lo contrario, o la pintura es orgánica y curvada como una topografía y las cintas son la grilla que está debajo del mapa, las ortogonales donde todo comienza. Ahora estoy empezando a pintar encima de las cintas y viendo cómo se mezcla pintura, líquido, mojado, con papel engomado (cinta) y color.

mc —¿Cómo empieza la geometría a dominar la evolución de tu trabajo? mp —Ahí hay un orden. Siempre estuvo esa obsesión por la grilla, la cuadrícula, la cartografía, el mapa. Quizás ordenar el mundo o algo así. Empecé a ponerlo en pintura o en piezas, quizás con las cajas, con los cuadrados y las diagonales, con las cintas. Esos trabajos arrancaron en paralelo: uno en Berlín y otro en Nueva York, 2009 y 2011.

Honestly, I was thrilled. So, to sum up, these pieces are based on the idea of painting as surface, as skin. With the strips of tape, it is a different thing. The goal is to create patterns on the surface, just like the corrugation on the surface of paintings. Maybe one is analogic (strips of tape) and the other digital (painting), even if it seems otherwise, or painting is organic and curved like a topography and the strips of tape are the grid underneath the map, the orthogonality behind everything. Now, I have started to paint on top of the tape and see how liquid, wet paint blends with adhesive paper (tape) and color.

mc —How did geometry begin to guide the evolution of your work? mp —There is an order there. I have always been obsessed with grids, graticules, cartography, maps. Maybe with ordering the world or something. I began to include it in paintings or pieces, maybe with the boxes, with the squares and diagonal lines, with the strips of tape. I began working on those collections of pieces parallelly: One in Berlin in 2009 and the other in New York in 2011.

Sistemas para pensar

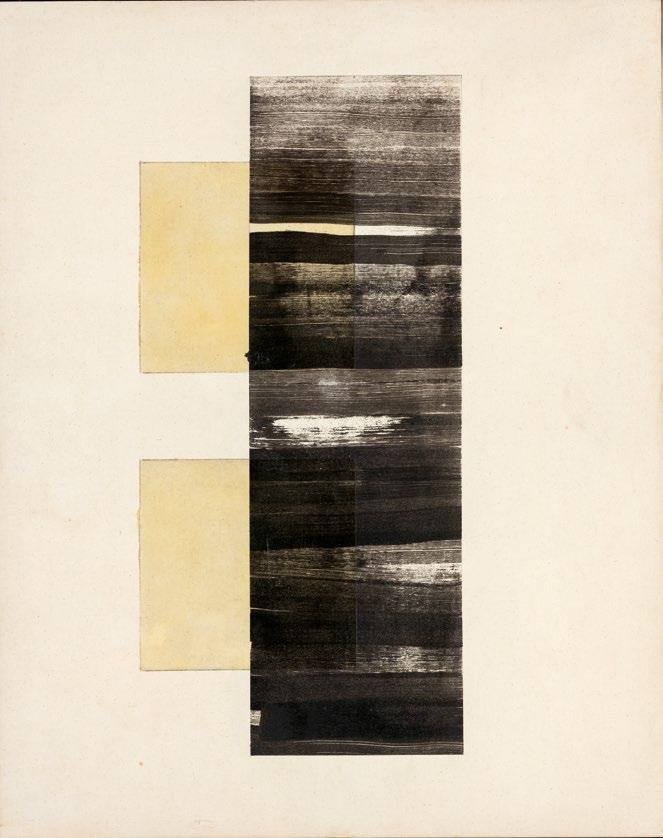

Barniz #1, 2010 Película de barniz 100 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Varnish #1, 2010 Varnish layer 39 × 39 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

1, 2016

De la serie «Ballena» Película de barniz sobre acrílico 120 × 80 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

1, 2016

From the “Whale” series Varnish layer on acrylic 47.2 × 31.5 in Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Sin título, 2007 Esmalte y barniz sobre lienzo 150 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Untitled, 2007 Enamel and varnish on canvas 59 × 39 in Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Sin título, 2007 Esmalte y barniz sobre lienzo 150 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Untitled, 2007 Enamel and varnish on canvas 59 × 39 in

Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Sin título, 2004

Esmalte y barniz sobre hardboard 60 × 40 cm

Colección Jorge de León

Untitled, 2004 Enamel and varnish on hardboard 23.6 × 15.7 in Jorge de León collection

Sin título (Mona Lisa), 2004 Esmalte y barniz sobre lienzo 25 × 25 cm

Colección del autor

Untitled (Mona Lisa), 2004 Enamel and varnish on canvas 9.8 × 9.8 in

Artist’s collection

Sin título, 2008

Esmalte y barniz sobre papel Arches 300 g 50 × 40 cm

Colección del autor

Untitled, 2008 Enamel and varnish on 300 g Arches paper 19.7 × 15.7 in Artist’s collection

#1, 2012 Se la serie «Pinceladas» Esmalte y barniz sobre papel Fabriano 300 g 60 × 40 cm

Colección Jorge de León

#1, 2012 “Brushstroke” series Enamel and varnish on 300 g Fabriano paper 23.6 × 15.7 in Jorge de León collection

Y, 2014 Barniz sobre lienzo 100 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Y, 2014 Varnish on canvas 39 × 39 in Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Y, 2014 Barniz sobre lienzo 100 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Y, 2014 Varnish on canvas 39 × 39 in Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

Y, 2014 Barniz sobre lienzo 100 × 100 cm

Colección Fundación Pablo Atchugarry

Y, 2014 Varnish on canvas 39 × 39 in Pablo Atchugarry Foundation collection

4 cuadrados negros, 2015 Barniz y esmalte sobre papel Fabriano 300 g 70 × 50 cm

Colección Jorge de León

4 black squares, 2015 Varnish and enamel on 300 g Fabriano paper 27.6 × 19.7 in

Jorge de León collection

Círculo, 2015 Carbonilla sobre lienzo 100 × 100 cm

Colección del autor

Circle, 2015 Charcoal on canvas 39 × 39 in

Artist’s collection

Cruz del círculo, 2010 Esmalte y barniz sobre lienzo 100 × 100 cm

Colección del autor

Circle cross, 2010 Varnish and enamel on canvas 39 × 39 in

Artist’s collection

martín craciun —Con la exposición Ballena (2016) llegaste al fin de una etapa. Uno podría encontrar un punto de inflexión de tu trabajo ahí, porque nunca llegamos al fin de una investigación, ¿no? A partir de ese momento te vas deshaciendo del barniz como medio, para utilizar materiales más crudos, por llamar de alguna manera a aquellos medios que no necesitan una preparación previa (catalizadores, disolventes, retardantes). Se me vienen a la cabeza las cajas con las diagonales, donde las diagonales se conjugan con los trabajos en barniz, y de ahí a la serie donde ensayás sobre las posibilidades de las diagonales ejecutadas con tintas; te gusta llamarlas las sepias. De ahí pasás a trabajar con triángulos, luego aparecen las cintas… Hay un proceso de radicalización del discurso que se repite constantemente. Se ve reflejado en tu trabajo y los movimientos en los distintos cuerpos de obra. martin pelenur Ballena parecería haber sido la síntesis del trabajo con un material, en este caso el barniz. La manera de darle fin a una investigación sobre el comportamiento de un material era lograr su autonomía; en este caso, librarlo del soporte. Entonces el desafío era generar películas de barniz para luego desmoldarlas y presentarlas en la sala, colgando. Me surge la idea, una vez más, de la Pintura como piel; me viene Eva Hesse y, a raíz de eso, tu idea de montar a lo Mark Manders y revestir la sala con nailon, como cámara de frío o frigorífico.

Una vez finalizado ese proceso aparece la pregunta de qué hacer, porque lo cierto es que venía de más de diez años pintando con barniz, al cual llamo trabajo húmedo, aunque paralelamente trabajaba con cintas,

martín craciun —With your exhibition

Ballena (Whale, 2016) you reached the end of a stage. One could call that a turning point for your work, as one never stops investigating, right? From that moment on, you started ditching varnish as a medium and favoring rawer materials, by which I mean those mediums that do not require any preparation (catalysts, solvents, retardants). The boxes with the diagonals come to mind, where the diagonals are conjugated with your varnish-based pieces, and then there is the series where you explore the possibilities of diagonals made with ink, which you like to call “sepias”. You then moved on to working with triangles, then the strips of tape made their appearance… There’s a constant radicalization of your discourse. Your practice, as well as the shifts within your various bodies of work, reflect it.

martin pelenur Ballena felt like the synthesis of my work associated with a certain material, in this case, varnish. The way of providing an end to my investigations about the behavior of a given material is to achieve its autonomy. In this case, to free it from its base. The challenge was, then, to create layers of varnish in order to later release and hang them in the space. Once again, the idea of painting as skin occurred to me, Eva Hesse came to me, which led to your idea of staging the show Mark Manders’ style, for which the showroom was lined with nylon, as in a cold storage chamber or a walk-in freezer.

Once that process came to an end, the question of what to do next appeared, because the fact is I had spent over ten years painting with varnish, which I call wet

trabajo seco. El qué hacer se transforma casi siempre en ejercicios de caligrafía en pintura. De ahí sale la serie de Sepias: trabajar formas puras dentro de un cuadrado de 10 × 10 cm con tinta de secado rápido. O la serie de pinceladas y ver cómo seca la pintura al agua en un pincel de 2". A través de estos ejercicios empecé a darme cuenta de que la repetición y la modulación me permitían expandir los trabajos, y así empiezan las cajas con su diagonal, pintadas sobre hardboard y luego sobre calcárea. El extremo de esta serie ha sido dibujar con óleo pastel sobre la calcárea, ya con la idea de mural.

mc —Cuando estabas en el taller de la proa, frente al Mercado del Puerto de Montevideo, la horizontalidad definió gran parte de tu trabajo. No podría entenderse tu obra sin considerar que fue pensada o mirada de manera horizontal. Hay una cuestión con el horizonte y ciertos medios líquidos que necesitan de la horizontalidad para funcionar, para quedarse quietos y reaccionar. mp —La primera respuesta básica es: gravedad. Estaba trabajando con un material acuoso, líquido; trabajaba en capas y necesitaba que secaran. Me interesaba que hubiera ciertas condiciones en ese secado, que tenían que ver con los tiempos, con la autonivelación —hablando ya de volumen en pintura—, cosas que solo pueden suceder si estás en horizontal. Ahí hay una primera pista. Después, me parece que uno tiende a pensar a los pintores trabajando parados o sentados frente al caballete, gestos que son más verticales. Mi trabajo siempre fue horizontal, aunque hay una relación con lo ortogonal. Horizontal para luego poner vertical. La mayoría de los trabajos han sido hechos de forma horizontal; recién en los últimos

work, even though, at the same time, I had been working with strips of tape, dry work. The process of deciding what to do almost always ends up turning into exercises of painting calligraphy. That’s the origin of the Sepias series: Working with pure shapes inside a 10 x 10 cm square using quick drying paint. Or doing a series of brushstrokes and watching the water paint dry on a 2” paintbrush. Through those exercises, it began to dawn on me that repetition and modulation allowed me to expand my work, which marked the beginning of the boxes featuring diagonals, painted on hardboard panels and then on limestone. The extreme end of this series was drawing with oil pastels on limestone, with the prospect of painting a mural in mind.

mc —When you used to work at that studio across from Mercado del Puerto in Montevideo, horizontality defined a huge portion of your artistic output. Your work could not be understood without taking into consideration that it had been conceived or beheld horizontally. The issue of the horizon and certain liquid mediums that require horizontality to work, to achieve stillness and react. mp —My first basic response would be: Gravity. I was using a watery, liquid material, working on layers that I needed to dry. I was interested in that drying taking place under certain conditions, which had to do with timing, with self-leveling (speaking of painting volume), which can only take place on a horizontal plane. Therein lies a hint. In addition, I believe people tend to think about painters standing up or seated when they work, which are rather vertical positions. My work has always been horizontal in nature, even though there’s a connection

dos o tres años empecé a pintar en vertical y es mucho más cómodo, además de permitir entender mucho más toda la historia de la pintura.

mc —Pasaste mucho tiempo usando lo horizontal, intentando transformarte un poco en un ingeniero químico. Mezclando thinner con barniz y catalizadores, esperando la reacción; intentando controlar la catalización para lograr en el craquelado un efecto visual, o un espesor, o un volumen; no solo el tono, el color o la materialidad, sino también la forma misma de la pintura, su estructura interior.

mp —Ahora he vuelto a trabajar en la superficie. Siempre fui un pintor de superficie y toda esa química que mencionás surge de trabajos en la superficie que tenían que ver con tiempo, cantidades y reacciones que encontré de forma azarosa. Me ponía premisas desde la ciencia. Cuando puedo repetir significa que tengo dominio y me permito volver a hacerlo. Luego me cuestiono: ¿qué quiere decir que estoy dominando una técnica? Creo que no hay nada inventado; lo que hacemos es ir descubriendo vínculos y relaciones sobre lo inventado. Fueron muchos años, sobre todo con los barnices, porque los círculos y otras cosas son gestos que surgen encima de esos trabajos.

mc —Ya en tu serie de obras negras de gran formato uno podía encontrar cierta vocación por lograr la veladura definida por una cantidad de solución, a partir de un solvente, una cuestión más asociada con el mundo de los procedimientos y, por consiguiente, la química. Pigmentos, solventes, soluciones… Ahí hay un punto que se reitera en lo que hacés, llevado al extremo y radicalizado con el tiem-

with orthogonality. Something horizontal that becomes vertical. Most of my pieces have been produced in a horizontal way; only over the past two or three years I started to paint in an upright position, and it’s much more comfortable, apart from helping me understand much better the history of painting.

mc —You spent a great deal of time working horizontally, trying to become a sort of chemical engineer. You mixed thinner with varnish and catalysts, waiting for a reaction, trying to keep the action of those catalysts under control to achieve craquelure as a visual effect, a thickness or volume; not merely the tone, color, or materiality, but also the shape of the paint itself, its inner structure.

mp —Now I’m back to working on the surface. I’ve always been a painter of surfaces, and all that chemistry-related stuff you mentioned arises from working on surfaces, where timing, quantity and randomly found reactions played a big part. I set science-based premises for myself. If I can replicate something, it means I have mastered it, so I allow myself to do it again. Then I wonder, “what does it mean to master a technique?” I don’t think we ever create anything new, what we do is discover connections and relationships between preexisting stuff. That happened over the course of many years, especially when it comes to varnishes, because the circles and other things are gestures that stem from those pieces.

mc —In your series of large-sized dark pieces, one could already detect an inclination towards achieving glazing through a solution, using a solvent, something more relat-

po. Es interesante hablar de la radicalidad, en momentos en que ser radical es casi un insulto. Observo que, con el tiempo, intentás empujar las cosas al máximo posible, pero lo posible es una construcción que se va moviendo. Cuando hiciste la exposición Ballena en la sala Dodecá de Punta Gorda, Montevideo, el barniz se separó del soporte. Es pintura porque está pensado desde la pintura; es un medio acuoso que se coloca, decanta y seca y crea una superficie, pero que logra librarse del lienzo para proponer pensar el no soporte. La exhibición presentaba estas pieles o cueros, como les dice Pablo Atchugarry, en un contexto de instalación muy sugerente. mp —Pablo lo mira con la mirada del cazador. Son las pieles del cazador y en sentido literal está bien, porque para mí eso era la piel de la pintura. Había logrado sacarle la piel a la pintura y tal vez ese sea el trabajo más importante que haya expuesto. Esa instalación y ese trabajo resultaron un logro; hice algo que pensé e imaginé durante muchos años, y tal vez fue como sacarme una obsesión de encima. No sé si lo volvería a hacer. Eran pieles y me parece que en términos de pintura era un trabajo muy rico. No puede haber algo más pintura que eso, salvo lo que decía Marcel Duchamp: que las latas de pintura son ready made.

ed to the procedural side of things; therefore, to chemistry. Pigments, solvents, solutions… You keep coming back to that, pushing and radicalizing it over time. Radicalization is an interesting point, as we live in a world where being radical is almost an insult. I have noticed that, over time, you have tried to push things to the max, but what’s possible is a shifting construct. When you held your Ballena exhibition in Montevideo’s Dodecá gallery, located in Punta Gorda, varnish was detached from its base. They were paintings because they were conceived as such: A watery medium applied on a base, decanted, and dried, but released from its canvas to suggest the idea of lack of base. The exhibition showcased those skins or pelts, in the words of Pablo Atchugarry, in the context of a very suggestive installation. mp —Pablo looks at it from the point of view of a hunter. They are a hunter’s pelts, and in a literal sense, it is accurate, because for me those were the skins of my paintings. I had managed to strip them from their skins; maybe it was the most important work I have exhibited. That installation and those pieces represented an accomplishment. I pulled off something that I had thought about and pictured for many years, and I sort of expunged an obsession I had. I don’t know if I would do it again. They were skins and, painting wise, it was a very rich body of work. Painting does not get any more painting than that, but for what Marcel Duchamp said: cans of paint are ready-made pieces.

Sistemas para intuir

Detour, 2016 Fotografía digital Caminata por el perímetro de la ciudad de Manhattan

Detour, 2016 Digital photo Walk along the perimeter of Manhattan

Así se llamaba la isla antes de que llegaran los europeos, ‘Isla de muchos cerros’.

El proyecto estaba enmarcado dentro de una idea más grande, que era recorrer el perímetro de islas pequeñas; pequeñas en el sentido de que el recorrido no llevara más de un día. Manhattan tiene una superficie de 87,5 km².

La primera isla que recorrí fue la de las Gaviotas, en Montevideo, y luego Gorriti, en Punta del Este, 2013 y 2014 respectivamente.

mannahatta project

Such was the name of the island before the europeans came: “Island of many hills”.

The project belonged to a broader idea of walking small scale islands, meaning it would not take more than a one day walk. The surface of Manhattan is 87.5 Km².

The first island I walked was “Isla de las Gaviotas” in Montevideo (2013), then Isla Gorriti in Punta del Este (2014).

Extractor Sudamérica, 2016 Mapa de Sudamérica y Oceanía Localización de extremos cardinales, centro y antípoda 29,7 × 21 cm

Colección del autor

Extractor South America, 2016 South America and Oceania map Cardinal extremes, center and antipode 11.7 × 8.3

Artist’s collection

líneas bue

Las recorridas por los buses de Buenos Aires partían del proyecto Líneas Bue, en el cual había trasladado las líneas de mi mano al mapa de la ciudad, y luego salía a recorrerlo. Si en el trayecto de la línea había transporte público, me lo tomaba.

líneas bue

The rides on Buenos Aires buses stemmed from the Líneas Bue project, in which I overlapped the lines on the palm of my hand to the map of the city and then went out to travel along them. If any given stretch of the line had public transport available, I would catch it.

Buses de Buenos Aires, 2008 Fotografía digital

Buenos Aires buses, 2008 Digital Photo

Extractor Voyeur Oeste, 2012 Fotografía digital

Extractor Voyeur West, 2012 Digital Photo

En el 2012 me propuse llegar a los cuatro extremos cardinales del territorio uruguayo, registrar imagen y sonido desde el amanecer hasta el anochecer filmando en una sola toma, para luego pasar las cuatro proyecciones durante el tiempo que durara la filmación.

In 2012, I set out to reach the cardinal extremes of Uruguay and register image and sound from dawn to dusk in one take. Later, I showed the four projections during the length of the film.

Recorrido del perímetro de la isla de las Gaviotas, en la ciudad de Montevideo. La isla se encuentra situada a unos trescientos metros de la playa Malvín. Registro: Adolfo Folle.

Hike along the perimeter of Isla de las Gaviotas Island. The island is located 300 meters from Malvin beach in Montevideo. Video: Adolfo Folle

Isla de las Gaviotas, 2013 Fotografía digital

Seagull Island, 2013 Digital Photo

Under the Bridge, 2016 Fotografía digital

Under the Bridge, 2016 Digital Photo

Keypad, 2014

El tablero funcionaba a través de una interfaz: N, E, O, S accionaban los respectivos videos de los puntos cardinales que estaban proyectados en una pared.

Keypad, 2014

The control panel worked through an interface N, E, O, S turned on the corresponding videos of the cardinal points that where projected on the wall.

martín craciun —Cuando conocí tu trabajo, hace más de diez años, ya nos conocíamos personalmente. Entonces tuve la idea de que formalmente estábamos lejos, pero, al mismo tiempo, había un interés común en ambos. Sentí que tu autodeterminación por llevar adelante una práctica y sostenerla, combinada con tu vocación por construir una carrera en un lugar extraño para el arte contemporáneo... Por aquellos años Punta del Este no era lo que hoy tenemos con relación a ese arte. No había ninguna pista de una Feria de Arte Contemporáneo, ni de galerías, ni instalaciones como la de James Turell o museos como el maca de Pablo Atchugarry. En ese contexto casi imposible es que te propusiste gestar La Pecera, tu espacio de producción y exposición, como mecanismo de supervivencia, y comenzaste a construir un ecosistema absolutamente propio, valiosísimo. Entonces dialogar, construir nuestra relación, fue un salvavidas para mí también. Yo buscaba cerrar procesos personales y nuestro vínculo me ayudó a afianzarme en la práctica curatorial, a entender cuál podría ser mi lugar en esta red. Creo que al abrirme la puerta a tu trabajo comencé con una fascinación que me ha traído hasta acá, a estar cerca de los artistas y acompañar su trabajo a través de los años. Trabajé años como artista, pero esto era completamente distinto. Soy muy intuitivo, intento serlo frente a la improvisación, que es algo que trato de evitar.

martin pelenur —Me encanta lo que decís y me ganaste de mano. A nivel intuitivo seguro viste algo y te acercaste. Primero me contactaste y luego propusiste un cambio en el taller que para mí fue magia. Re-

martín craciun —We had already met in person when I became acquainted with your work, over ten years ago. Back then, I had the impression that, in terms of form, our approaches were dissimilar, but, at the same time, we shared a common interest. I felt that your determination to follow and stick to certain practices, combined with your vocation to pursue a career in an unusual place for contemporary art, like Punta del Este at the time, was not what we have today in connection with that art. There wasn’t a Contemporary Art Fair in place, or galleries, and neither were there installations like James Turell’s nor museums like Pablo Atchugarry’s maca. It was in that extremely adverse context that you decided to set up La Pecera, your production and exhibition space, as a survival mechanism, and began to engender a unique and extremely valuable ecosystem. Thus, starting a conversation and bonding with you was a life-saver for me. I was looking for closure in some aspects of my personal life and our relationship helped me establish myself as a curator and understand what my place within this network could be. I think that by opening myself up to your work, I triggered a fascination that has led me here, a position of proximity to different artists thanks to which I can monitor the latter’s production over the years. I worked as an artist for years, but this is completely different. I’m very intuitive, I try to keep that up in the face of improvisation, which is something I try to avoid.

martin pelenur —I love what you just said, and you beat me to the punch. At an intuitive level, you must have spotted something and approached us. First, you reached

sultaste como un mago sacando el conejo de la galera, y ese fue un momento trascendental. La intuición es el modus vivendi, el modus operandi, tal vez una forma de conocimiento/no conocimiento muy poderosa. Me gustaría pensarla como un tema de la dualidad que todos los seres humanos tenemos dentro. Henry Bergson, el filósofo, estaba muy interesado en ver si se puede sistematizar la intuición, y eso me lleva a pensar si uno puede disciplinarse en la intuición. Creo que lo potente es tener una cantidad de conocimiento y luego el bicho intuitivo alimentado, aceptar la intuición y dejarse llevar por ella.

mc —Me resulta interesante aplicar la intuición a la forma de producir el conocimiento. A propósito, vayamos a Extractor, esa serie de proyectos en el territorio con bajo dominio tecnológico sobre los medios que utilizás. Montás una cámara y con tres o cuatro herramientas materializás un proyecto que termina siendo un ejercicio sobre el paisaje, sobre una manera de producir y aprehender que tiene más que ver con la intuición que con la reflexión crítica y la investigación acerca de ese tipo de arte. Extractor, de extraer, imagino, es un proceso para recoger información, pero también una forma de vida, un statement. No puedo entender que algo más que la intuición te lleve a hacer esas hazañas de darle la vuelta a la isla de Manhattan, caminar horas en Buenos Aires o llegar a los extremos cardinales del Uruguay, proyecto que mereció el premio de la Alianza Francesa. mp —Ese es el principio de Extractor, que son los extremos cardinales del Uruguay y su centro cardinal. Sin duda, los proyectos de este tipo se inician así y tal vez la pintu-

out to me, and suggested a change to my workshop that did wonders for me. You were like a magician pulling a bunny out of a top hat, which was a transcendent moment. Intuition is a modus vivendi, a modus operandi, maybe a very powerful form of knowing / unknowing things. I like to think of it as a duality that every human being carries inside. Philosopher Henry Bergson was quite keen on systematizing intuition, and that makes me think about whether you can discipline yourself through intuition. I think there’s nothing more powerful than possessing a large amount of knowledge, as well as the intuitive bug well fed, in order to embrace intuition and let it guide you.

mc —I’m interested in applying intuition to knowledge-producing mechanisms. Speaking of which, let’s talk about Extractor, that series of projects conducted on the field with little technological control over the mediums you use. You set up a camera and with three or four tools you materialize a project which ends up being an exercise on the landscape, on a way of producing and apprehending things that has more to do with intuition than with critical thinking and researching. I guess Extractor, from extracting, is an information-gathering process, but also a way of life, a statement. I can’t think of anything beyond intuition as a driving force behind such feats as going around the island of Manhattan, walking across Buenos Aires or reaching Uruguay’s cardinal points, a project that was granted an award by Alianza Francesa.

mp —Those are the origins of Extractor: the cardinal extremes and center of Uruguay. Without a doubt, that’s how projects of these kind begin, and that’s also how paint-

ra también arranque así. Una chispa muy potente genera esa fascinación, algún tipo de construcción mental que luego se traduce en construcción de la realidad. Ese es un punto muy fuerte; la realidad es lo que construimos, y lo que construimos es básicamente lo que pensamos.

En estos trabajos de Extractor, empecé desde el final y traté de llegar a algún tipo de principio. ¿Cómo llego a los extremos cardinales del Uruguay? No lo sé; arranqué viendo mapas —me gusta mucho leerlos— y en algún momento vi la imagen de cuatro puntos en el espacio, que físicamente es imposible ver a la vez. Y así comenzó el proyecto. De ahí partieron todos los proyectos: algo que me llamara la atención en el mapa, algo que tal vez no debería estar, como una línea recta, un ángulo —generalmente son artificios—, y por otro lado investigar nociones de límite y frontera.

mc —Y la intuición te trajo adonde estás. mp —Intuición y obstinación. Obstinado por hacer las cosas a mi manera, seguramente caprichosa, pero propia. Uno tiene clara la intuición, ampliamente descrita, por la negativa. Aparece esa vocecita interior por la que sabemos cuándo es no. Cuando no lo querés hacer, cuando la vas a cagar, generalmente algo te lo dice. La intuición late, tal vez muy fuerte, cuando no es. A veces es más fácil por oposición, por el negativo, por el absurdo. Y cuando es, puede ser muy suavecita y tenés que seguir ese viento fresco. La curiosidad y la aventura son cosas que me convocan.

mc —¿Cómo organizás tu trabajo?

mp —Pienso que trabajo por proyectos, aunque, de todas maneras, tengo ese hilo de

ing begins. A very powerful spark ignites that fascination, a mental construct that ends up giving reality it shape. That’s a very compelling point; reality is what we build, and what we build is basically what we think.

In these pieces of Extractor, I started at the end and tried to arrive to some kind of beginning. How did I get to Uruguay’s cardinal points? I don’t know; I began looking at maps – I enjoy reading them very much – and, at some point, I saw an image of four points in space, which are physically impossible to watch at once. That is how the project started. Every project stemmed from that: something that caught my attention in the map, something that didn’t belong there, such as a straight line, or an angle –they are generally artificial –, and, on the other hand, the exploration of the notions of boundary and frontier.