T H E P O L I T I C I A N S W E D E S E RV E ?

do we have the

THE POLITICIANS WE DESERVE? Christopher Clark YE AR 13

T

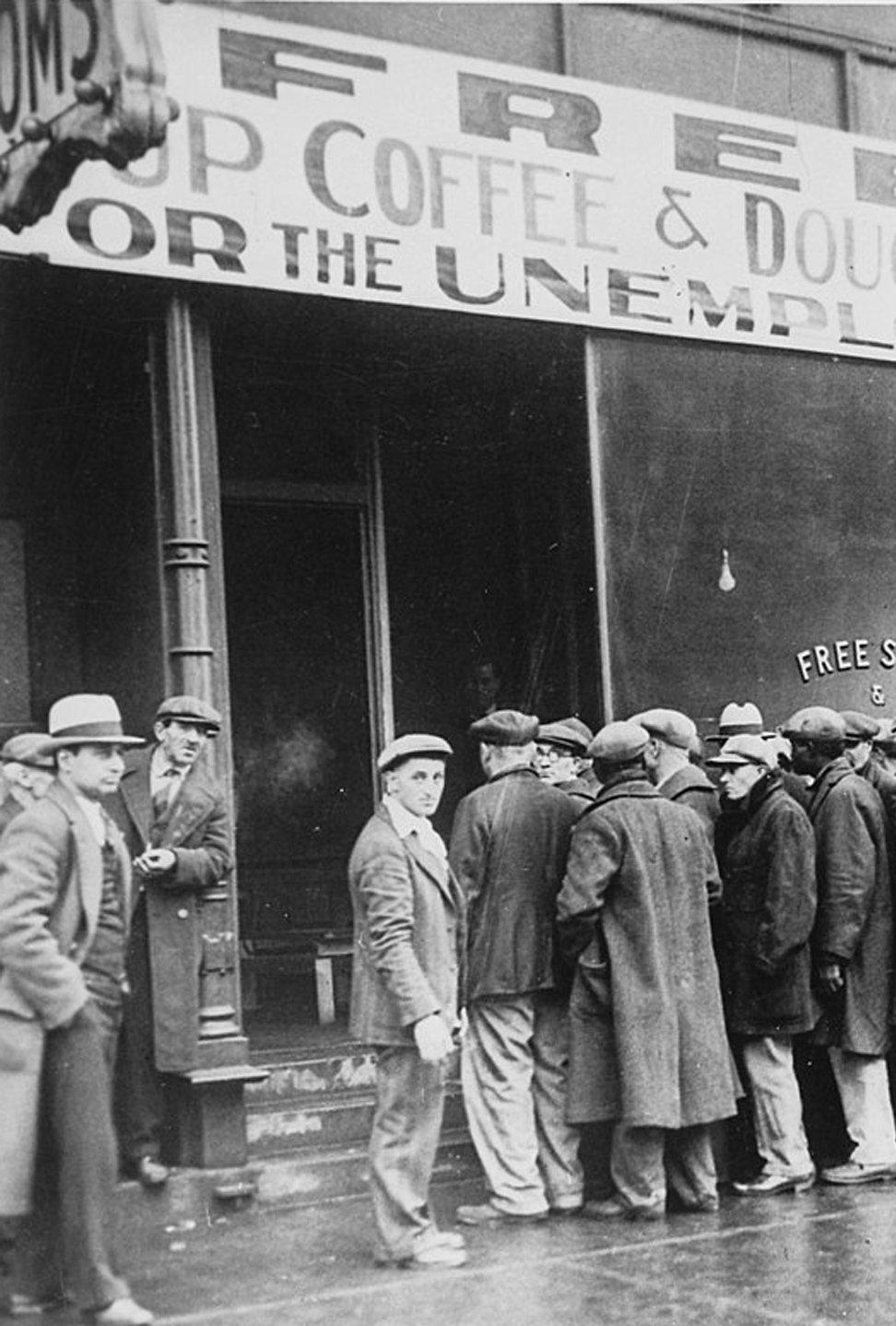

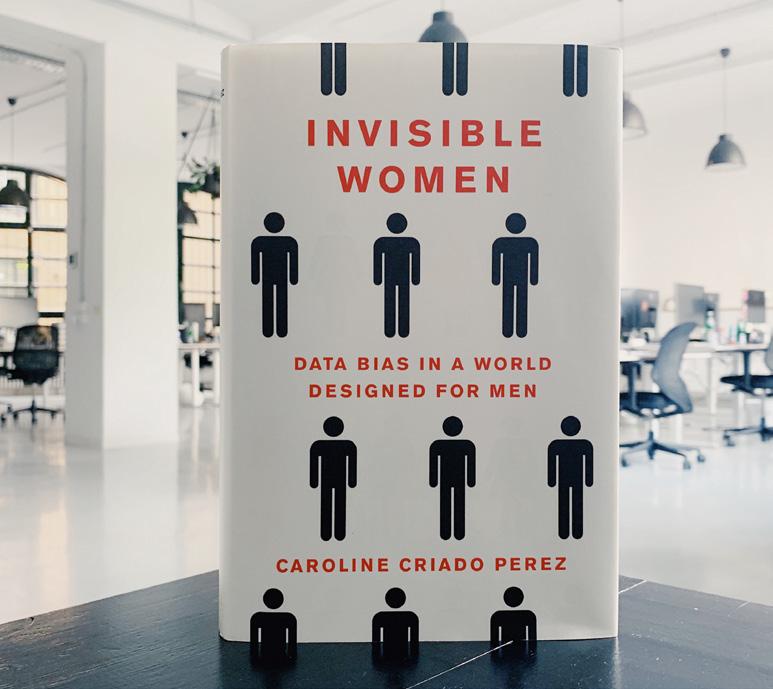

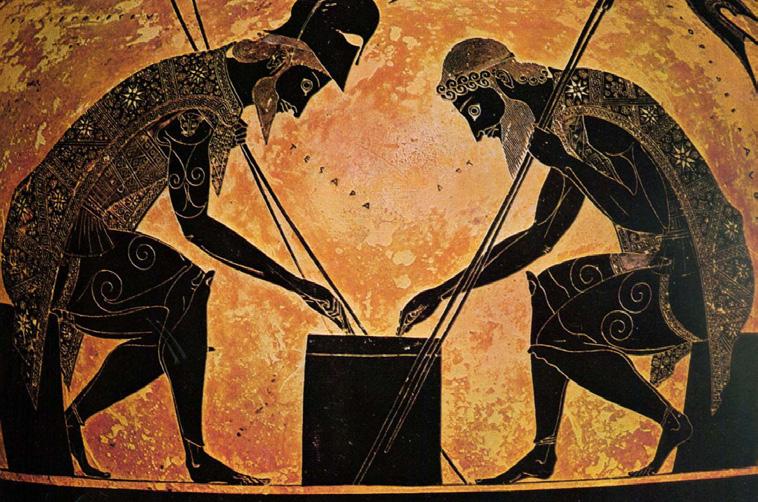

o preserve voters’ faith in the political system, it is essential that it continues to mirror the beliefs, aspirations and values of the electorate. In recent years, there has been a particular concern about the role of truth and facts within politics, ‘fake news’ and deliberate manipulation of information seemingly more and more prevalent – blamed by some on news organisations and others on politicians. The most obvious example of this, in a Western democracy, is the presidency of Donald Trump. While lies, corruption and incompetence have been reported features of his administration for the past four years, they have been thrown into even starker relief by the Covid-19 pandemic. The President has untruthfully claimed that everybody can access tests, that he anticipated the pandemic before it happened, that he has ‘total authority’ over states and their governors. His lies and manipulations have been enthusiastically amplified by propagandistic outlets such as Fox News (pulled from UK broadcast). In our own country, we have had to put up with politicians making a series of outrageous claims, such as the need for a £1,600 floating duck house paid for by the public (this actually happened during the scandal over MPs’ expenses in 2009), false assertions about NHS funding on the side of a bus during the Brexit campaign in 2016 and bogus reports about Saddam Hussein’s possession of Weapons of Mass Destruction in 2002. There has been a steady erosion of public confidence in government honesty and truthfulness, leading to an increasingly poisonous and distrustful atmosphere. It is not exactly news that politicians are capable of telling lies; dating back at least as far as Thucydides’ portrayal of Alcibiades, historians, dramatists and novelists have been unsparing in their presentation of politicians’ often unscrupulous behaviour. However, it is of concern that those in power increasingly refuse to apologise or acknowledge any guilt or shame when wrongdoing or falsehoods are exposed, whether Donald Trump or Dominic Cummings. Such behaviour is fuelling an atmosphere of cynicism and alienation among the electorate that is dangerous; people may either turn to alternative,

less democratic options (as they are in Hungary and other countries) or tune out of politics altogether. According to Peter Pomerantsev, in his account of Putin’s Russia, Nothing is True and Everything is Possible, such apathy and confusion is exactly what authoritarians from Putin to Trump, Orban to Bolsanaro wish to achieve, employing weapons of mass distraction. Should nothing be kept secret? Well, yes, national security means that some confidentiality is required in certain cases, such as war or espionage, but too often in the UK the Official Secrets Act and related legislation is used to cover up embarrassments or corruption rather than protect the nation. In such situations, it is not only acceptable but necessary to leak to the press in the interest of the public finding out the truth – although, of course, this will often involve agonising moral and ethical decisions on the part of whistleblowers and journalists alike. To those who argue that we should just relax as mendacious politicians have been around for a couple of millennia or more, I would reply that this is not something to feel complacent about. Voters should be able to trust their politicians, broadly, and take their words at face value, should be able to have politicians who represent the best of our aspirations (Lincoln’s “better angels of our nature”) rather than our lowest instincts. If this does not prove possible, then perhaps an alternative will be to turn politicians into puppets, each equipped with a wooden nose. Desperate times may require desperate measures.

PORTSMOUTH POINT

www.pgs.org.uk

73