5 minute read

The Mirrors of Literature: From Epic to Dystopia Louise Shannon

Louise Shannon YEAR 13

T H E M I R R O R S O F L I T E R AT U R E : from EPIC to DYSTOPIA

The Iliad, c. 760 BCE

The history of literature stretches back millennia to the beginnings of human civilisation. Despite all the revolutions and upheavals – cultural, political, technological and linguistic – that have taken place in the intervening centuries, the novels of today are still connected enough to the ancient texts of writers from Homer to Shakespeare, that, for all of the cultural differences, they can all be categorised under one term: literature. Acknowledging this invites a question: just how many parallels can really be identified between the numerous literary styles throughout history?

In antiquity, the classical prose and poetry of ancient Greece and Rome served as the forerunner of modern

literature. Greco-Roman epic poems such as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid piloted the contrasting and sometimes paradoxical themes of conflict and peace, honour and dishonour, love and hatred. These thematic patterns would continue to exist in later pieces of fiction and can still be identified in the works of poets and authors alike today. Literary techniques now considered the standards of writing had their origins in classics; for example, the early forms of ‘stream of consciousness’ are observable in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, leading to the development of depictions of internal emotions in the narrator now expected in modern novels. It was these early narrative devices which perhaps led to the rise of distinguishable monologues and soliloquies first popularised centuries later. Evidently the foundations of modern literature are rooted in antiquity, despite drastic changes in syntax, contemporary literature mirroring that of the earliest periods of writing.

In the centuries following the end of classical antiquity, there were a number of thematic and stylistic changes in literature. In the Dark Ages, Old English epics, such as Beowulf, combined Christian motifs with tales of warriors involved in conflict and victory that mirrored Greek and Roman texts. Meanwhile, writers such as Bede and Boethius began to divert away from epic heroic themes to philosophical and religious matters; the hagiography, or a biographical account of saints, became a staple of medieval texts, moral rather than warrior heroes. Secular literature also underwent a revolution in this period; in the twelfth century, Geoffrey of Monmouth pioneered fantastical elements in prose with his stories of Merlin and King Arthur and served as one of the forerunners of the fantasy genre. He also influenced other writers such as Chretien de Troyes who helped create the genre of romance, for example the love story of Guinevere and Lancelot.

Thus, the medieval era was one both of continuity and revolution in literature. During the same medieval era, the GrecoRoman genre of satire, developed by the Roman lyric poet Horace, helped shape Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, written in the latter half of the 14th century; today, Chaucer is often referred to as “the Father of English Poetry” but what made him so transformational was his deep learning in French and Italian literature, each of which was heavily

influenced by classical writers.

It was not only narrative techniques and styles which had been retained from literary beginnings, however, but cultural depictions. One particularly influential example can be drawn from the medieval Islamic world, in particular Tales from One Thousand and One Nights, better known in the West as The Arabian Nights, tales drawn from Arabian and Persian myths and legends, featuring the likes of now widely-known characters such as Aladdin, Sinbad and Ali Baba, who with various motifs from these narratives have served as inspiration for so much global literature that has since followed, particularly within the genres of fantasy and science fiction to this very day.

One of the most revolutionary eras in literature was the early-modern period of history, between the 15th and 17th centuries, not only resulting from the invention of the printing press in Europe but also the Renaissance that reintroduced European scholars and writers to classical texts that had been thought lost for over a thousand years. The widespread distribution made possible by printing helped literacy to spread as did the rise of grammar school education in England that produced some of the greatest writers of any era: William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson, who combined classical education with commercial flair to write some of the greatest dramas ever written. Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre reflected the fact that ecclesiastical themes were gradually becoming outdated, plays with biblical themes replaced by texts influenced by the early genres of tragedy and comedy first created by Greek playwrights such as Aeschylus and Euripides. Shakespeare is today credited with merging tragedy and comedy in a revolutionary way, echoing but reinventing the ancient styles.

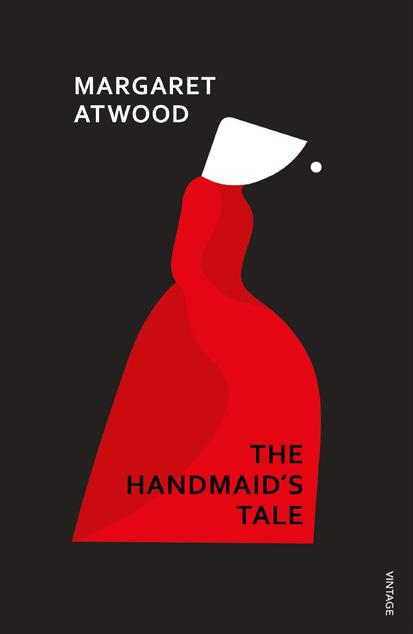

An increasingly wealthy middle class ready to read and buy books made the invention of the novel in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century possible, with pioneering novelists including Daniel Defoe and Samuel Richardson. In the late 1700s, Romanticism, spearheaded by William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge represented one of the most radical breaks with previous literary styles in history, seeking to create a new form of literature based on authentic personal experience. In turn, the Realist and Naturalist movements, influenced by science and technology, developed in the late nineteenth century as a reaction against Romanticism. One offshoot of the novel was the Gothic, popularised by Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto and brought to philosophical as well as literary maturity with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1816; the Gothic was a popular genre that ranged from religion and philosophy to mythology and science to love and horror. The Gothic’s fascination with the irrational aspect of human behaviour anticipated the psychology of Sigmund Freud by over a century and helped influence modernist and eventually postmodernist literature and theory in the twentieth century, that reacted against traditional motifs, often by reworking them in ironic and parodic ways. A notable example of post-modern Gothic in the 1980s was the work of Angela Carter

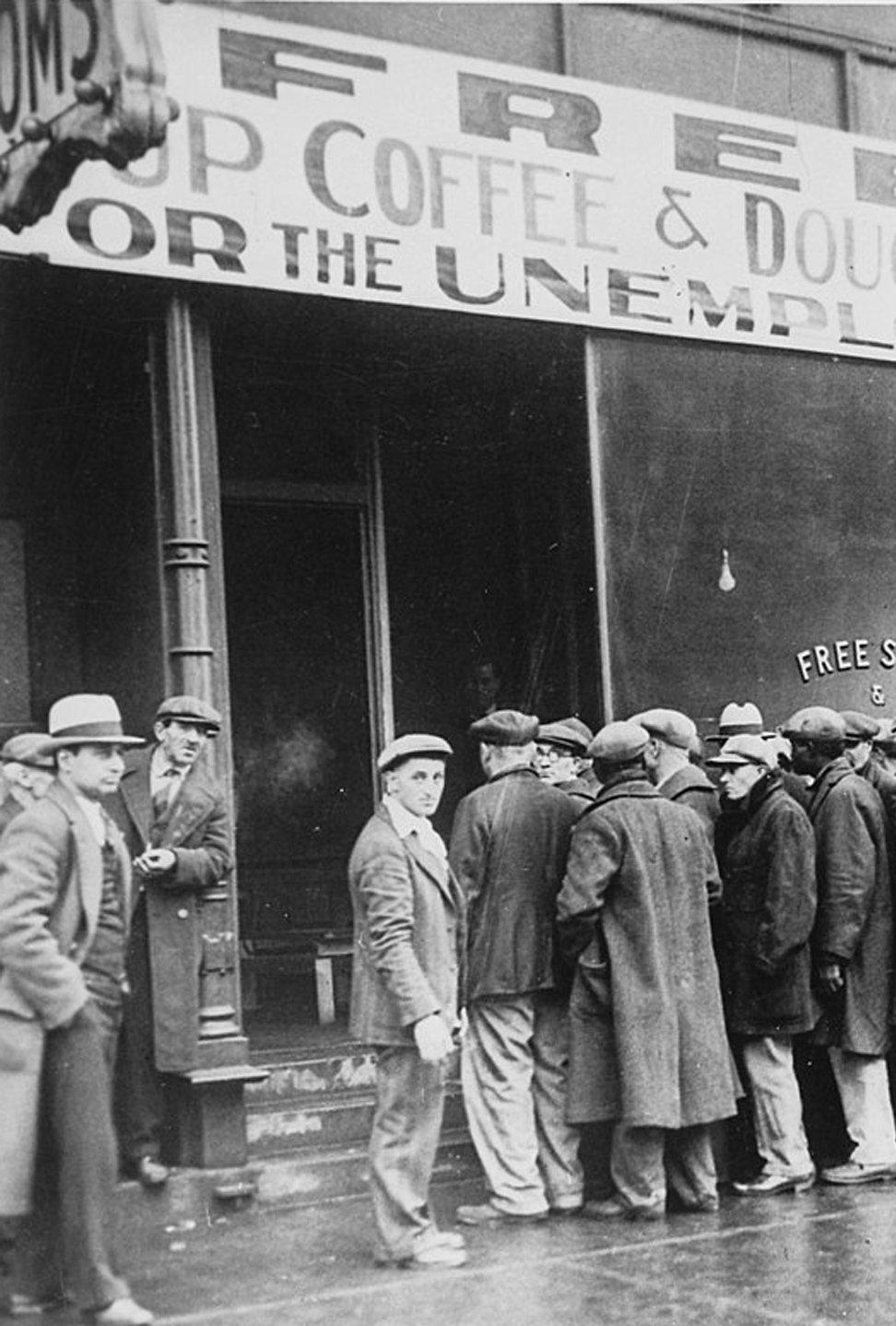

The Handmaid’s Tale, 1985

and Margaret Atwood, in works such as The Bloody Chamber and The Handmaid’s Tale; the latter focused on the dystopian future but featured many stylistic features and motifs from the past. Thus, the ghost of historical literature continues to be clearly present in today’s most popular genres and varieties.

At first glance, the passage of time and evolution of languages appears to have led to essential differences in the structure, style and substance of writing. Furthermore, the plethora of themes and motifs, genres and movements might initially lead one to assume that the literary features of our modern age don’t bear close resemblance to historical works. Notwithstanding this, analysis of literary patterns shows that modern texts do, in fact, mirror antiquity in both cultural depictions, underlying subjects and aesthetic choices. This revelation indicates that, in spite of landmark changes over thousands of years, the historical roots of literary ideas and style hold a much greater influence over modern writers than widely acknowledged.