10 minute read

Utopia or Dystopia? How Literature and Film Predict Our Future Haleigh Smith

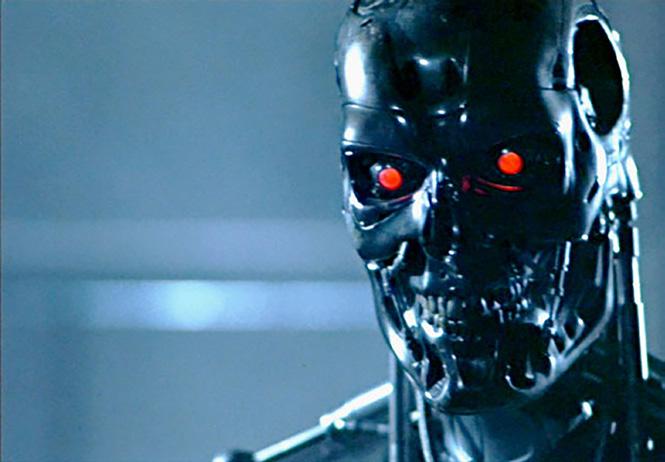

The Terminator by James Cameron (1984)

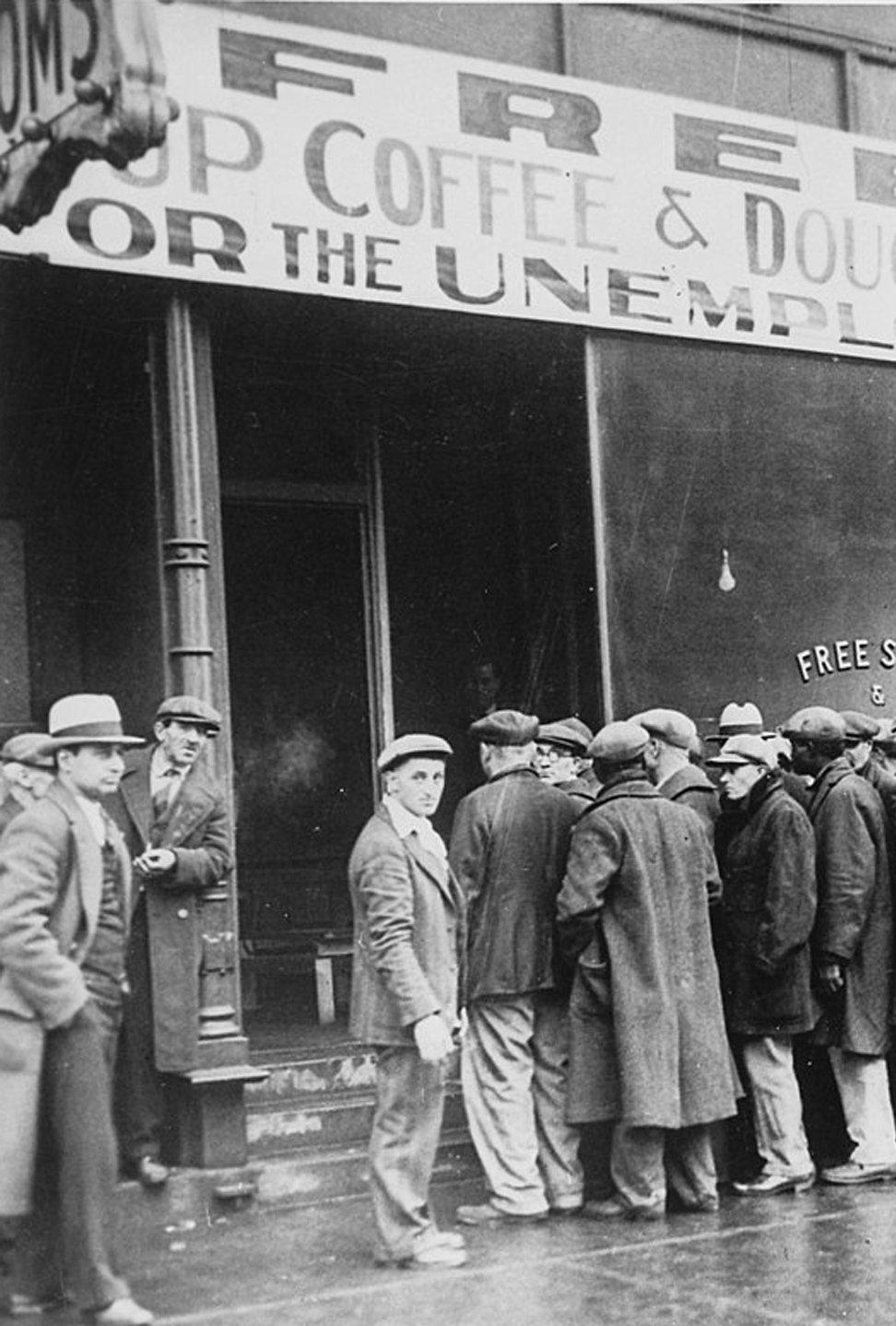

TWO OF THE TOP THREE SURVEILLANCE SOCIETIES ARE DEMOCRACIES: THE USA AND THE UK.

In a 2010 interview with Paris Review, science fiction author Ray Bradbury said: “Science fiction is any idea that occurs in the head and doesn’t exist yet, but soon will, and will change everything for everybody, and nothing will ever be the same again.” However outlandish they may have seemed when first articulated, “Ideas, when mobilised, become the templates of thought and practice.”. Many authors and filmmakers, over the centuries, have conjured many ideas that, at the time, didn’t seem possible, yet have, in the intervening years, become, wholly or in part, a reality. These futuristic inventions and ideas, expressed in novels and movies past and present, emphasise the creativity of the human mind and remind us that “Even the flimsiest ideas rooted in prejudice and ignorance make history and form public culture”. It can be argued that the depiction of the future in science fiction has influenced our development as a society by transforming many of these ideas into reality.

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, science-fiction is the mode of novel that has caught the attention of many, not least because of their fascination with innovative ideas that have become more of a reality during our era of dizzying technological progress. George Orwell’s 1949 novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four touches upon the themes of propaganda and totalitarianism, as well as philosophical issues such as the nature of identity and individuality, particularly in relation to the state. Orwell predicted the mass surveillance that characterises our twenty-first century society, as well as abuse of government control and the cult of personality, which we can certainly see in government and politics today, even in supposedly democratic societies. In Orwell’s novel, the reader is presented with an all-seeing totalitarian

UTOPIA OR DYSTOPIA?

How Literature and Film Predict Our Future

Haleigh Smith YEAR 13

presence, Big Brother, used by The Party to instil a sense of loyalty but also fear. This devotion to Big Brother is illustrated at the end of the Two-Minute Hate ritual, where an entire group of people break out into a slow and deep rhythmic beat, chanting 'B-B! ... B-B! ... B-B!'. In the novel. The Party uses technology and surveillance to maintain this cult of personality, using television screens to watch people as well as having people spy on everyone else to maintain fear. The phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become part of our everyday vocabulary to describe the mass surveillance society in which we live, in the era of Amazon’s Alexa, Siri and Google Home. Amazon has admitted that its employees listen to customers’ voice recording from many of their Alexa-enabled smart devices in order to “help improve conversation quality”. The same social media companies use algorithms to keeps track of every gesture, comment, like, purchase and search we make online, which is then used to predict further preferences and helps control our behaviour and our choices (streaming companies such as Netflix use similar technology to curate a personalised catalogue of entertainment based on viewing history).

Equally troubling is the use by governments of mass surveillance cameras. The United States of America has approximately 15.3 cameras per 100 citizens, followed by 14.4 in China and 7.5 in the United Kingdom – which means that two of the top three surveillance societies are democracies, not obviously authoritarian states. Increasingly, cameras are disguised as mundane objects like tissue boxes, wall clocks, water bottles and smoke alarms to make them more inconspicuous than ever; the only reason many of us know about them is that they have surfaced to be purchased on Amazon. Whistleblower, Edward Snowden, has revealed that America’s National Security Agency (NSA) “specifically, targets the communications of everyone. It ingests them by default.” The theme of mass surveillance presented in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, seen as quite far-fetched when the novel was initially released in 1949 (particularly in democratic countries such as Britain), seem less science fiction and more a predictive mirroring of the technology used in today’s society.

Even earlier than Orwell, HG Wells, in his novels, made predictions that seemed outlandish at the time, but have proved prescient. In particular, his novel, The World Set Free, published in 1914 before the First World War, suggests that mankind will eventually destroy itself; it imagined a uranium-based hand grenade that "would continue to explode indefinitely" over thirty years before the first atomic bomb created by the Manhattan Project in 1945: including “Fat Man” and “Little Boy” dropped with such devastating effect on the Japanese cities of Nagasaki

Metropolis by Fritz Lang (1927)

and Hiroshima. Wells argued that, as a result of these scientific “advancements”, humanity would destroy itself; he suggested that “the only possibilities of the case were either the relapse of mankind to the agricultural barbarism from which it had emerged so painfully or the acceptance of achieved science as the basis of a new social order.” We can see this faith in science reflected in our own times, as the Government insists its Covid-19 strategy is driven by “the Science”. However, although HG believed science could bring improvements in society he also understood the dangers in placing too much faith in science at the expense of a moral framework. The 146,000 deaths in Hiroshima and 80,000 deaths in Nagasaki (excluding the deaths caused by the initial explosion) were appalling. However, we should not forget the more recent estimates by United Nations agencies and Greenpeace International, in 2005, that, between 4,000 and 90,000 deaths had resulted from the 1986 Chernobyl disaster. In our own twentyfirst century, there were, in 2014, 4,760 nuclear warheads in the American weapons inventory and 4,3000 warheads in the Russian military inventory alone. Wells’ prophetic argument that we needed a global governmental body to maintain a stable civilisation influenced the decision of President Roosevelt and others to form the United Nations following the Second World War; possibly their most significant recent pronouncement has been the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, passed on July 7th, 2017: “comprehensive set of prohibitions on participating in any nuclear weapon activities. These include undertakings not to develop, test, produce, acquire, possess, stockpile, use or threaten to use nuclear weapons.” However, Wells did not just inspire the peacemakers, he also influenced American-Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard, who, having read The World Set Free, conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933 and wrote a letter for Albert Einstein’s signature that would initiate the Manhattan Project to build the first atomic bomb. What more powerful and destructive proof can there be of Ray Bradbury’s description of science fiction as “any idea that occurs in the head and doesn’t exist yet, but soon will”.

Modern cinematic technology has enabled the movie industry to present science fiction ideas, such as those pioneered by Wells, to an ever-wider audience. Again, what once seemed fantasy has become reality; the fact that our own lives are increasingly screen-based (not least during the confinement of Covid-19) has perhaps made us feel increasingly that we are each living in a movie, expanding our own concept of what we mean by ‘reality’. Arguably, the most popular and influential science fiction film of the last forty years is James Cameron’s futuristic apocalypse, The Terminator (1985), which presents a world in which humanoid machines grow an autonomous consciousness and take over the world by force. AI today, although not yet at the stage depicted in Cameron’s film and its sequels, has developed to an extent some find exhilarating others unsettling. The use of AI and robotics globally, from commercial to military, is increasing exponentially; in September 2018, the Pentagon committed to spending $2 billion over the coming five years to “develop the next wave of AI technologies”, while in January 2019, rumours emerged that Russia was developing an autonomous drone which would be able to take off, accomplish a given mission and land without any human interference. Currently, a Taranis-armed drone is under development in the UK, said to be “the most technically advanced demonstration aircraft ever built in the UK”. This use of autonomous technology in the military mirrors the science fiction ideas demonstrated in Cameron’s film, where military drones are seen to roam the skies with the capability of deploying bombs and artillery.

The expansion of humanoid robots is another area in which Terminator and other twentieth century science fiction films (including Metropolis, made as early as 1927!) have been prophetic. Sofia, a humanoid robot has the capability to hold an intelligent

conversation; CEO of Hanson robotics Dr David Hanson says that “20 years from now, I believe that human-like like those will walk among us”, and will be “indistinguishable from humans”. Furthermore, Kuri is said to have a personality, awareness of its surroundings and the ability to learn from experience, while Kurata, 3.8 metres tall and weighing 5 tons, features a BB Catling gun with the ability to deploy 6,000 rounds per minute. The development of the Cyberdyne system Model 101 that possesses a metal endoskeleton seems to make the vision of Cameron and other science fiction directors a reality already; it also seems probable that we will only become more reliant on such technology during our lifetimes.

Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall (1990) follows a character, Douglas Quaid (played, like the Terminator, by the actor Arnold Schwarzenegger) who discovers that his entire life is actually a false memory and the people who planted his memories now want him dead. We are not quite there yet. However, what is of interest here is that, in one scene, Doug jumps into a driverless taxi, known as a “Johnny cab” which has a humanoid robot posing as the driver to make conversation. In the 21st century, although cars may not be at the point of flying, driverless vehicles or vehicles with less dependence on humans are now very much a reality and, predicted by many, to be the dominant mode of private transport over the next decade or so. The most famous example has been produced by Tesla, with autopilot features and self-driving capacity: ‘Traffic Aware Cruise Control’ matches the speed of your car to the surrounding traffic; ‘Autosteer’ assists in steering within a clearly marked lane and traffic-aware cruise control; ‘Navigate on Autopilot (Beta)’ helps with navigating the car off of roads, into other lanes and taking the correct turn which automatically engages the turn signal or indicator; ‘Autopark’ helps with parallel and perpendicular parking with a single touch; ‘Summon’ moves your car out of a tight space using a mobile of key; ‘Smart summon’ navigates more complex areas and parking spaces, and manoeuvring around objects to come and find you in a parking lot. Robotics company Nuro has partnered with retail company Kroger to create an unmanned grocery delivery which has been tested on customers in four zip codes, providing evidence for the flexibility in the use of autonomous technology to our benefit.

Thus, we can see how inventions and technology of our own era have been predicted by visionary authors from Wells to Bradbury and imaginative directors from Fritz Lang in the 1920s to Paul Verhoeven in the 1990s whose minds were more innovative than their time, mirroring not only the present in which they lived but the future. Ideas and events once portrayed as science fiction through literature and cinema are now our reality. This leaves us to wonder what other ideas we currently think of as science fiction will come true within our lifetimes or maybe beyond. As Ray Bradbury, born exactly one hundred years ago, at the beginning of the technologically transformative twentieth century, wrote: “Ideas, when mobilised, become the templates of thought and practice.”. Folakemi Odofin YEAR 8

MIRROR

As I stood in front of this mirror, The thoughts of a perfect me were illustrated. Over time it became clearer, The perfect me that I created, Mimicked all the hobbies that I enjoyed, However, wasn’t kind and caring but full of deceit. My hopes of a perfect image were being destroyed. What if I change the perfect me, let me repeat As I again stand in front of this mirror The thoughts of a perfect me were illustrated. Over time it became clearer That a perfect me could not be located. Then I realised the perfect person I could be, Has always been inside of me.