17 minute read

Speeding Mirrors: The Magic of Classic Motorsport Matt Bryan

Matt Bryan YEAR 13

SPEEDING MIRRORS

THE MAGIC OF CLASSIC MOTORSPORT

For me there are two distinct types of engineering: engineering and engineering. The former is perfectly sufficient in every way, it’s the act of designing and constructing something that functions well and predictably without much fanfare, but is simple enough in its very nature. An aqueduct is a good example - a structure that diverts water from one place to another, as they have done for millennia, to facilitate irrigation and human life. But an aqueduct is in no way an example of engineering, and neither is an electric whisk or HS2.

So how do you identify an elusive piece of engineering? Well, it is no mean feat, but I will try to guide you by the hand through my train of thought.

I’ve been a petrolhead since before I was born; my parents drove around in a 1972 MGB Roadster until my mum’s eight-month bump prevented her from reaching the veneer steering wheel. I must’ve been to every motoring museum imaginable from here to the Lakes and seen every episode of Wheeler Dealers and Top

Gear twice over. It must run in the family as even my grandad could be classed as a ‘boy racer’, with a slew of Escort XR3s,

TR7s and TTS’ lining his logbook. I gawp out the car window or on the street at anything rare, slightly fast or vaguely interesting, and have quite a sad habit of reciting engine displacements and lengthy histories, even when no one cares to listen - but that’s what makes me a petrolhead. So, with all that, you’d expect I’d be a big Formula One fan. Not at all.

I can respect the engineering of a modern F1 car, with their carbon-fibre fuselages complete with enough downforce to collapse a small star in the corners. Engineers squeeze close to a thousand horsepower out of a unit smaller than most Ford

Fiestas; they implement regenerative braking systems that turn the heat from deceleration into even more dizzying speed. Teams invest hundreds of millions in having the best engineering staff tweak their cars within the strict technical specifications, but the cars are still highly similar in order to make racing fairer. The

problem is that today’s F1 car, however impressive and bedroomwall poster-worthy, is boring - they are too regulated, too focused on marginal gains and too clinically refined. They are certainly well-engineered, but on the other hand, well, not engineered.

F1 is well established as a series consisting of closed-circuit races, typically around 60 laps for distances in the range of 200mi and always less than two hours. From year to year, teams, circuits and cars might slightly change, but the World Drivers’ Championship is awarded to the driver with the most points based on Grand Prix finishes. From my point of view, it’s highly formulaic, with extended rulebooks meaning one race is much like the next - but that’s not just my opinion. The concluding laps of the 1992 Monaco Grand Prix are legendary amongst the petrolhead public. Nigel Mansell leading for almost the entire race, until a puncture forced him to pit; Senna then taking the lead, holding off an advancing Mansell who was much faster

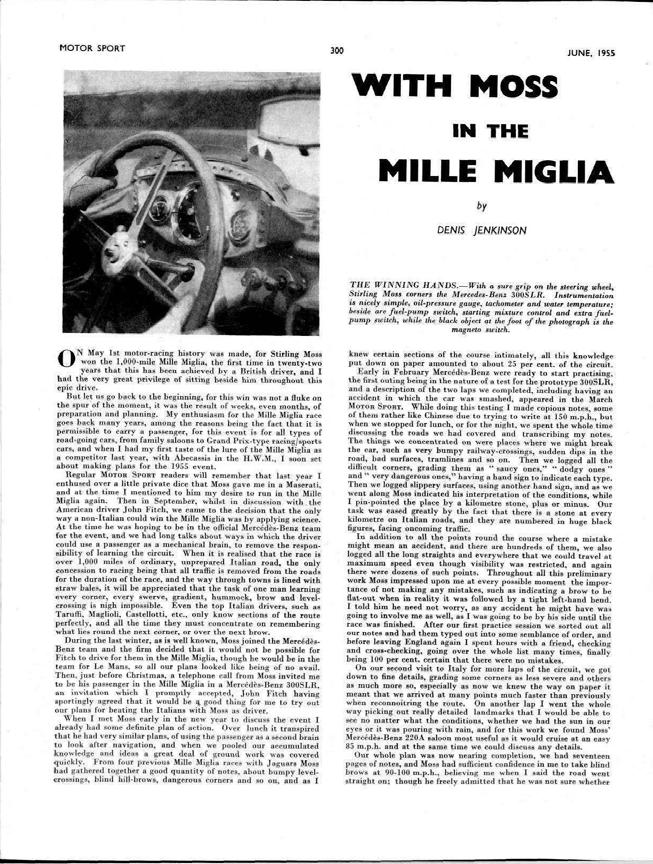

Moss and Jenkinson in the #722 300 SLR at the 22nd Mille Miglia.

on newer, grippier tyres. This cat and mouse chase continued for the next five laps of the infamously tight street circuit, with Mansell trying overtake after overtake on a track only just wide enough for two cars. Senna would hold off Mansell to take 1st place, but in the process they created a spectacular ten minutes of pure racing.

The point of mentioning this? It’s widely argued that these ten minutes almost three decades ago are better than the entirety of F1 in the last twenty years. It hasn’t always been this way; in the past, motor racing was raw and passionate - not just because it was dangerous and untamed, not because the drivers were silverscreen cool rather than Weight Watchers spokespeople. It was exciting because the cars meant something and were the essence of the sport. Sponsorship and stringent calculation have replaced the blaring V12s of yore and the air thick with rubber. Part of the excitement of motorsport you see in Pathé films from yesteryear is the close-proximity, wheel-to-wheel racing, partly due to the benefit of drafting behind other cars. With today’s F1 cars, drafting is no longer viable; with the aerofoils designed for fast solo laps, sitting behind another car means turbulent, ‘dirty’ air that in fact reduces downforce, meaning that the thrill of close quarters racing is truly a thing of the past. Their once joyous engineering has lost its soul, becoming merely engineering in the process.

Back in 1953, when men were men and cigarettes were healthy, the FIA held the inaugural ‘World Sportscar Championship’, a racing series that had evolved from wealthy gentlemen throwing their four-wheeled toys around for fun, to a full blown professional series. It was only now that the world’s most prestigious manufacturers saw racing as a way to develop technologies and aid sales and reputation, so their support and the ruthless competition between them fuelled what would be the start of motorsport as we know it. Its list of races reads like a roll of honour: Sebring, RAC Tourist Trophy (at Goodwood & Silverstone), The Carrera Panamericana. Perhaps the most famous and glamorous, and one of few still held to this day, is the 24 Hours of Le Mans; it and the arduous one-thousand kilometre endurance races at the Nürburgring, Monza and Spa were staples.

Monza has since been radically redesigned, but the original ‘Pista Magica’ or ‘Magic Track’ had huge banked corners that meant racers were close to top speed for the majority of a lap. Its straights were long and open, designed for the very first race cars, before the introduction of chicanes to slow cars down to safer speeds. But the 50s and 60s were truly a golden age; a period when cars were raced flat out by their fearless drivers whether they would make it through the whole race or fall dramatically short. Driving these cars at the limit on circuits intended for half their power meant huge strain on brakes, tyres and powertrains, and averaging close to 130 miles an hour meant few made it without gearbox failure or blown engines. Endurance racing was fiercely popular and fashionable, but what was more fierce was the nationalism of its supporters. Two now-infamous races sum up the spirit of motor-racing in its golden age, both held in Italy and fought out by the best manufacturers and drivers from across the globe - the Targa Florio and the Mille Miglia.

The Targa Florio was the world’s oldest race, an epic tour of the Island of Sicily founded in 1906. The first race covered 3 laps of the Island, around hairpin scattered mountain passes, through picturesque Sicilian villages and orchards on rugged rural roads and down to the majesty of the Mediterranean, the winner averaging just thirty miles an hour over a gruelling nine-hour race. The scenery encompassed the rich culture of a developing Italy and its enduring natural charm. Think narrow, hardlypaved roads twisting onwards amongst olive trees and rural sunbaked rooftops that hadn’t changed in centuries à la the original Godfather’s Corleone, Sicily sequences (or that Galaxy advert with CGI Audrey Hepburn, if you prefer less organised crime) and

you won’t have something half as visually breathtaking. It was arguably the continent’s biggest race, dominated by Italian drivers and legendary cars from Alfa Romeo, Lancia and Maserati. The first 40 races saw 36 Italian champions in 29 Italian cars - certainly one nation dominated. But by the 50s, the race had developed into a solo start event, where cars went off in intervals around a slightly shorter circuit lined with thousands upon thousands of local spectators. But the really astounding part? The race was always carried out at full speed, on public roads - drivers spend countless hours practising short circuits, whereas on open roads each corner could be a complete surprise, and very easy to misjudge. The Targa was the greatest test of a driver’s innate skill, but an even greater test for the engineers to build something robust enough for a thousand kilometres of weathered public roads, but light and powerful enough to do so quickly and reliably, reaching the line in as few pieces as possible. It was under such conditions that Porsche would make a name for themselves.

Ferdinand Porsche founded his engineering firm in 1931, designing tanks and what would become the Volkswagen Beetle. However, post-war Germany saw a huge parts vacuum, meaning the brand’s first true production car, the 356 (coincidentally one of the most beautiful cars ever produced) was based heavily on Beetle parts. This meant an unusual rear-engine, rear-wheel drive layout with air-cooling that would soon become Porsche’s trademark. Putting the engine in the rear gave unique handling characteristics as the centre of mass was further shifted back, giving Porsche’s earlier cars a far nimbler front end. But with the 550, Porsche established a complete dominance in small-engine racing and set a new precedent for what a true race-car could be. Other cars of the era were designed around a powerful, typically large and exotically complex engine with a fine-tuned handling platform, that is chassis, suspension and wheels, to make the most out of it. But the 550 looked like nothing else - with sleek lines at a time when aerodynamics was close to

A 718 RS 60 makes a pit stop during the 1960 Targa Florio.

alien, and a body that hugged the tarmac thanks to a flat-4 engine

(in which the cylinders are horizontally opposed, giving a block with lesser height) which further lowered the centre of mass. The car was quick to accelerate, especially out of corners, and all 90 ever produced were aluminium silver, reflecting sunlight as they passed. Oscar-nominated James Dean bought a 550 Spyder in 1955 to race at Salinas, but never started - he died in a head-on collision days before.

If the 550 was successful, then the 718 that succeeded it was indescribably so. It won the Targa three times, facing cars with much larger engines, but with superior handling and a monstrous power-to-weight ratio, it would still triumph. Derek Bell recently drove the same 718 that won the 1960 Targa Florio, stating, “Once you get it on song, get up to 7,000-plus-revs, it just wanted the hell driven out of it. And the fact you could

brake so perfectly, flick it into a corner, put the power on… It was absolutely amazing”. In the modern era, cars are tweaked and tuned to the track - fast tracks require more downforce and less cornering grip and so on, but for the Targa Florio, “the world’s most torturous race”, how do you tune a car for some 800 unique corners? You don’t, possibly can’t. You build a car to the best of your ability and vision, with so much love, testing and knowledge that it ascends to having its own identity. The 718 was the culmination of a decade of Porsche’s sublime race design and was a quintessentially perfect car. Clear skies as a 718 RSK speeds past the carabinieri at the 1962 Targa Florio. Porsche too had a real love affair with the Targa Florio, the race that essentially made the brand and helped develop a lineage of great sports cars - the 718 birthed the 911 and the Porsche formula endures to this day. A roof with a removable section was first introduced on the 1966 911, designated ‘Targa’; a demonstration of how much one race meant for the brand. But the Targa Florio was still not the greatest race of its era; some might say that the Mille Miglia has that honour. Porsche never won the race, but remained competitive in the Ferrari-dominated field; in fact, the 550 was so low that Hans Herrmann drove his under closed railway barriers during the 1954 edition of the race. So, how could this race have been more exciting than the unadulterated romp through the Sicilian countryside?

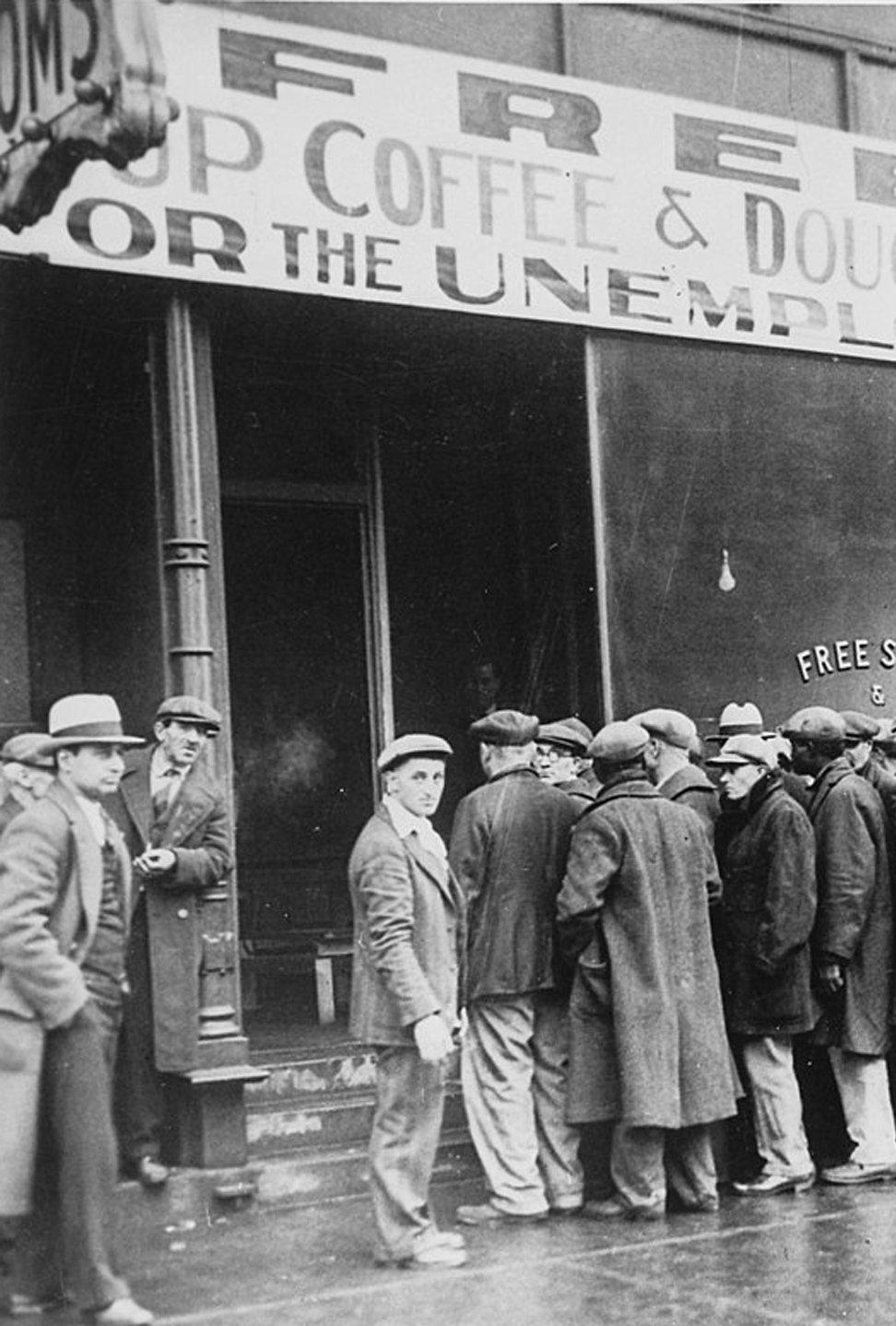

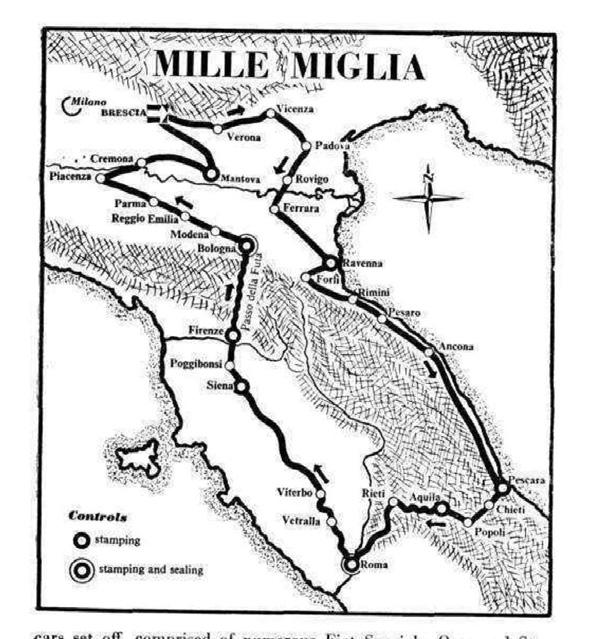

The Mille Miglia was just as its name suggested - a thousand miles of closed public roads from Brescia at the foot of the Alps down along the Adriatic and through the ancient streets of Rome, before returning to Brescia in the North. The race encompassed everything it meant to be Italian, starting near Milan, the hub of Italian racing and car culture as well as close to the headquarters of Alfa Romeo, Ferrari and Maserati, in addition to the design giants of Bertone, Pininfarina and Zagato. In a post-Fascist Italy, the spirit of motorsport and the pride Italians took in their cars helped bring a nation together; it became part of their identity,

with the Mille Miglia, and its estimated five million spectators

(more than 10% of the population) serving as testament to that. The race developed some of the greatest cars of all time in its 30- year run, dominated by Ferrari’s latest raucous V12 racers in the hands of men like Ascari, the twice-F1 World Champion who lived and died in ‘prancing horses’. But even with the glorious sights of cherry-red Italian racers screaming around their natural habitats of vineyards and piazzas, one car stole the show in 1955: a refined German piloted by a refined Brit.

In 1955, the sadly-now-late Stirling Moss won what has long since been labelled as ‘the greatest race of all time’, making him and the Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR that took him at an average of 98.53 miles an hour for over 10 hours, instant international icons. Stirling had said “I’m certain it’s my greatest win,” but by far the most brutal and intense race imaginable - having to part spectators on narrow roads whilst he “had a horrible feeling only

(Motor Sport Magazine Archive, June 1955) (from Racing Demons – Porsche and the Targa Florio)

20-30% (of the other drivers) were competent to (race), most of them were off the road burning in the first twenty kilometres”. Moss was one of the greatest drivers of a generation, beating Juan Manuel Fangio, the five-time F1 champion, as he excelled at the intense concentration needed to drive a thousand miles of road almost blind. He was one of few racers to opt for a co-pilot, others considering it dangerous or marred by previous deaths; Denis Jenkinson, a journalist from Motorsport, and Moss made a symbiotic team - Jenkinson compiled an 18ft scroll of notes stored in the car, and a system of fifteen hand signals helped them set a new event record. But even with the talents of Moss and his team, he would admit that the car played a huge part in what would become the greatest motorsport victory of all time; “I can’t think of any other car in the world that would have given me the opportunity to achieve the speeds we did.” The 300 SLR was a pure-bred racer like no other. Its sleek silver lines in Elektron magnesium-alloy gave it Art Deco charm, but the innate illusion of speed that made it look like it was doing 180 on the start line. With huge side-exit exhausts and emblazoned with a red 722 to denote Moss’ 7:22 am start, it was almost a dogfighter for the road, but with a huge number of pioneering technologies. The SLR took a 2.5 litre Mercedes-Benz F1 engine and bored it out to three litres and 310 bhp - at a time when the average car had thirty. It used more efficient mechanical fuel injection, developed for the Luftwaffe’s 109, and the engine was mounted at 33o, lowering the centre of mass and improving handling and aerodynamics. Its eight-cylinders in a line was an unusual set up, typically as a long crankshaft introduces flex and power loss, so the car took its drive from the middle of the engine block using an additional gear. Mercedes engineers had created a car so fast that they had to solve their own new aerodynamic problems, and a car so beautiful that the road-going 300 SL, or ‘Gullwing Coupé’, the timelessly charming fastest road car in its day, has been voted ‘Sportscar of the Century’. That’s what you call engineering.

But to fully comprehend the 300 SLR and its hallowed contemporaries, one cannot just recite their victories and describe their elegance, they must be experienced. Those grand

old racers make a noise like nothing else, and in the days before acoustic insulation and effective silencers, the roar of the engine was the only radio (much like the soundtrack to ‘C’était un rendez-vous’). On start-up, the SLR crescendos to a rich, gritty growl before ebbing to an uneven purr; at high-revs, the gearbox and differential sympathetically whine with every adjustment whilst the engine continues on its thunderously symphonic crusade through the gears. The pure sound and the wornin smell of petrol that clings to any clothing is not something you get in a modern car, nor is the feeling it invokes easy to describe. It’s almost an induced flashback to an age you’ve never lived, when you could feel the road beneath the floor; when the car was untameable, except for by a select few who could get somewhat close.

Following the 1955 Le Mans disaster, when an SLR overturned into the crowd at 125 mph, killing 84, MercedesBenz retired from racing for 34 years, making the car the last of its kind. The ‘golden era’ of motorsport had produced such technical development that the sport was almost too fast and unruly for its own good - the Mille Miglia was cancelled forever in 1957 after a Ferrari 335 S blew a tyre and took 11 lives, and the Targa Florio saw numerous restrictions until its cancellation in 1977. For many, that would be the end of motorsport as they knew it, and perhaps the end of its most revered era. Ludicrously powerful F1 cars took centre stage in the 70s and 80s, but never quite reached the same unmistakable magic of those that came before.

Way back when petrol was five pence a litre and ABS and traction control were unheard of, race cars were a different species, ‘widowmakers’ that would lift wheels in the corners and lift off completely in the straights; there was something special ingrained in their DNA. They were slow and inefficient, made of materials insufficient for the forces they had to withstand and far from technically perfect. But even without downforce, driver aids and hybrid systems, they were still perfect from an engineering perspective; full of character and quirks that elevate all the calculations and craftsmanship from blueprint to masterpiece. Not many have stumbled upon those pearly gates since, but when they have, you can feel it. The raw silver finish favoured by German manufacturers and later Ferrari’s 250 GTO amongst others is reportedly an engineer’s choice; the folk story is that Mercedes engineers had to lose a kilogram to scrape into the weight category, so they reduced the car back to aluminium bodywork. Regardless of the truth, the “Silver Arrows” as they were known dazzled like mirrors on the track, speeding by in a fashion that would give Narcissus just enough time to fall in love with them, just as many have done in the past. Engineering is the application of science to solve problems, but with problems as immense as winning thousand-mile road races in record time, surely you strive to make a solution as breath-taking, spine-tingling and unforgettable as possible? That’s why, when I grow up, I want to be an engineer. Samantha Todd YEAR 12

GLASS

I’ll place my hand up to this wall I might try to break it I might just stand and stare looking at that faint face look back at me I can’t tell is it disappointment that paints this window a stainedglass figure of me.

But it’s not a window that you will find easily It’s kept at the back far from sight and if you notice it pray to God it’s not depicting hell.

They say “Eyes are the window to the soul” but what if that window is cracked and broken does that mirror what’s behind it?