Mirror of Modernity:

Naomi Smith

I

YE AR 13

t can be argued that King Lear is the most unendurable of all Shakespeare’s plays. in Act V, in particular, the sheer number of deaths on stage is deeply uncomfortable. Moreover, the tragedy of the characters’ deaths are made even more unbearable by the fact that Gloucester and Lear experience a mental lift just before their deaths; the audience is granted a glimmer of hope which is quickly torn away. Finally, the relatability of King Lear in comparison to Shakespeare’s other tragedies such as Hamlet or Romeo and Juliet is greater now as the play still holds great universal relevance for a 21st-century audience, thus making the tragedy more uncomfortably familiar to a modern audience because it holds up such an uncomfortable mirror to our own society. Firstly, the great death-ridden scene in the final act of the play is deeply unsettling and difficult for an audience to watch. Whilst the death of one or two protagonists is commonplace in a typical tragedy such as is the case with Romeo and Juliet in the final scene, in King Lear, the audience is heavily burdened with mass death and the deeply uncomfortable image of the stage littered with five bodies. Shakespeare leaves us exhausted, saddened, questioning why this has happened and what the true moral lesson of the play is. As Aristotle addressed in Poetics, a tragedy arouses pity and fear, for an emotional release, and that at the climax of the play the audience is granted a ‘catharsis’ of these emotions, left with a moral lesson. However, despite the death at the end of many tragedies arguably granting a satisfying release, the overwhelming image of death in Act V Scene 3 is startling and invokes deep melancholy, even horror, among the audience. In addition, the lexical field of death is emphasised by the final stage direction, ‘Exeunt with a dead march’. The ‘dead march’ is a sound effect of music, suitable for a funeral. The image of death with the music of a funeral further reinforces the atmosphere of complete sadness and overwhelming unendurability. Moreover, the tragic frame of ‘LEAR with CORDELIA in his arms’ enhances the poignancy of the scene, the image invoking a deep sense of pathos amongst

20

P O RT S M O U T H P O I N T. B LO G S P OT.CO M

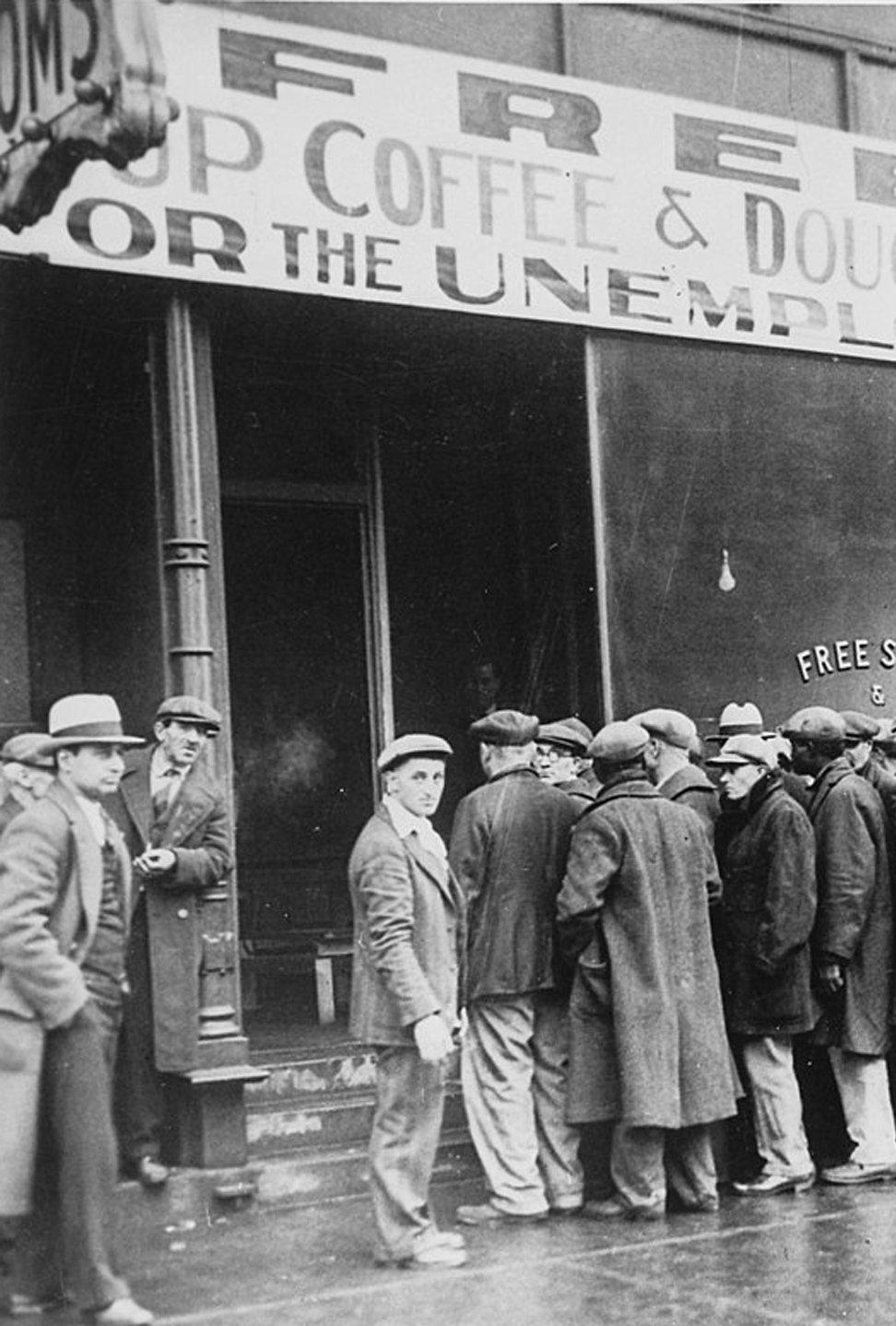

the audience at the sight of a father holding his dead daughter. This is a further example of the recurring theme, that there is an inversion or order within King Lear; it is unsettling that the young Cordelia has passed before her elderly, ill father. This tragic event has occurred in the wrong order, death has taken place unnaturally and the knowledge of this makes the sight not only of mass death but the frame of Lear holding Cordelia deeply upsetting. The natural injustice is highlighted by the line, ‘my poor fool is hanged’. The adjective ‘poor’ is pitiful, invoking sorrow whilst ‘fool’ acts as a term of endearment as well as connoting youth, therefore, furthering the sense of pathos that Cordelia has died too young. Moreover, it also reminds the audience of Lear’s other ‘child’, the Fool. The double reference implies that the Fool too has died, particularly as he has not been on stage since Act III, Scene 6. It can be argued that the fool’s line, ‘I’ll go to bed at noon’ (3.6) marks his death in the play with going to ‘bed’ as a metaphor for sleep, ultimately a far more romanticised presentation of death than the gruesome depiction in Act V Scene 3. The shift from a romantic to gruesome presentation of death in the final scene signifies Aristotle’s tragic ‘fall’ in Lear’s tragedy, how death becomes ugly and commonplace. Ultimately, Lear’s fatherhood is ripped from him with not only all of his daughters dying but arguably the figure he acted mostly as a father towards throughout the play, the Fool. He has lost both his kingship in the public sphere and his fatherhood in the private. However, it is also likely that Lear simply refers to Cordelia as a ‘fool’ out of love. It is argued that at Shakespeare’s time of writing both the Fool and Cordelia would have been played by the same actor, a young boy, and therefore cannot be on stage at the same time. This would explain why the Fool does not appear in Acts Four or Five, rather than his death. In many ways what makes King Lear the most unendurable of all Shakespeare’s plays is the way in which the mass violence eerily mirrors the horrors of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In the Jacobean era, Hamlet may have been considered the greatest tragedy, with King Lear, viewed as an overly violent and unrelatable dark play. However, in a modern context a western audience has witnessed, in recent history, two world wars which sparked mass death, deep inhumane tragedies such as the Holocaust and many terror attacks with modern weapons killing many instantly, something which a Jacobean audience would have been blind to. The way in which Lear anticipates the torments of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, as well as its bleak, absurdist, postreligious philosophy, is what helps to make King Lear Shakespeare’s most terrifying but also recognisable play to a modern audience. R. A. Foakes in his book Hamlet Versus Lear, 1993 says that we are likely to see King Lear as Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy as it chimes with the anxiety and pessimism which world events have made common over the last century. A Christian reading may argue that whilst Lear’s suffering throughout the play is long and arduous his death in the final scene is fairly quick and painless. In Shakespeare’s time a quick and painless death was seen as a reward for a life lived virtuously, with long and painful deaths being granted to sinners. Perhaps his earlier madness led him to