Louise Shannon YE AR 13

T H E M I R R O R S O F L I T E R AT U R E :

from EPIC to DYSTOPIA

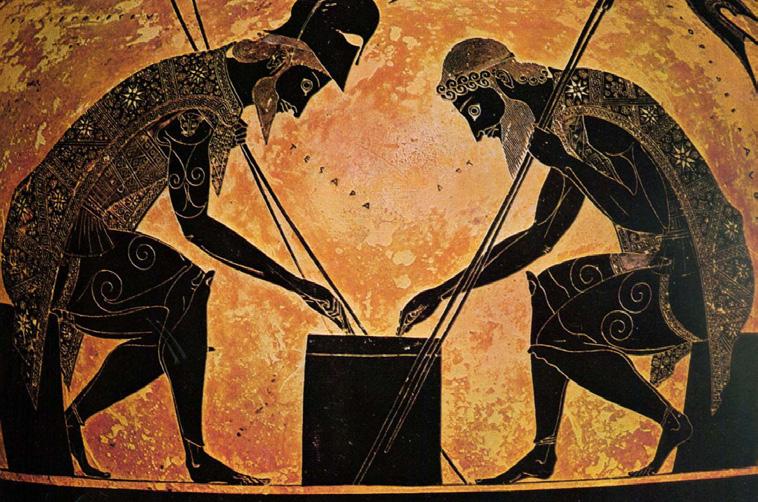

The Iliad, c. 760 BCE

T

he history of literature stretches back millennia to the beginnings of human civilisation. Despite all the revolutions and upheavals – cultural, political, technological and linguistic – that have taken place in the intervening centuries, the novels of today are still connected enough to the ancient texts of writers from Homer to Shakespeare, that, for all of the cultural differences, they can all be categorised under one term: literature. Acknowledging this invites a question: just how many parallels can really be identified between the numerous literary styles throughout history? In antiquity, the classical prose and poetry of ancient Greece and Rome served as the forerunner of modern

18

literature. Greco-Roman epic poems such as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Virgil’s Aeneid piloted the contrasting and sometimes paradoxical themes of conflict and peace, honour and dishonour, love and hatred. These thematic patterns would continue to exist in later pieces of fiction and can still be identified in the works of poets and authors alike today. Literary techniques now considered the standards of writing had their origins in classics; for example, the early forms of ‘stream of consciousness’ are observable in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, leading to the development of depictions of internal emotions in the narrator now expected in modern novels. It was these early narrative devices which perhaps led to the rise of distinguishable monologues and soliloquies first popularised centuries

P O RT S M O U T H P O I N T. B LO G S P OT.CO M

later. Evidently the foundations of modern literature are rooted in antiquity, despite drastic changes in syntax, contemporary literature mirroring that of the earliest periods of writing. In the centuries following the end of classical antiquity, there were a number of thematic and stylistic changes in literature. In the Dark Ages, Old English epics, such as Beowulf, combined Christian motifs with tales of warriors involved in conflict and victory that mirrored Greek and Roman texts. Meanwhile, writers such as Bede and Boethius began to divert away from epic heroic themes to philosophical and religious matters; the hagiography, or a biographical account of saints, became a staple of medieval texts, moral rather than warrior heroes. Secular literature also underwent a revolution in this period; in the twelfth century, Geoffrey of Monmouth pioneered fantastical elements in prose with his stories of Merlin and King Arthur and served as one of the forerunners of the fantasy genre. He also influenced other writers such as Chretien de Troyes who helped create the genre of romance, for example the love story of Guinevere and Lancelot. Thus, the medieval era was one both of continuity and revolution in literature. During the same medieval era, the GrecoRoman genre of satire, developed by the Roman lyric poet Horace, helped shape Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, written in the latter half of the 14th century; today, Chaucer is often referred to as “the Father of English Poetry” but what made him so transformational was his deep learning in French and Italian literature, each of which was heavily