Quarterly The Journal of the white house historical association Spring 2023, Number 69

The White House and New York WHITE HOUSE HISTORY

the white house historical association

Board of Directors chairman

John F. W. Rogers

vice chairperson

Teresa Carlson treasurer

Gregory W. Wendt secretary

Anita B. McBride president

Stewart D. McLaurin

Eula Adams, Michael Beschloss, Gahl Hodges Burt, Merlynn Carson, Jean M. Case, Ashley Dabbiere, Wayne A. I. Frederick, Deneen C. Howell, Tham Kannalikham, Metta Krach, Barbara A. Perry, Ben C. Sutton Jr., Tina Tchen

national park service liaison: Charles F. Sams III

ex officio: Lonnie G. Bunch III, Kaywin Feldman, Carla Hayden, Katherine Malone-France, Debra Steidel Wall (Acting Archivist of the United States)

directors emeriti: John T. Behrendt, John H. Dalton, Nancy M. Folger, Knight Kiplinger, Elise K. Kirk, Martha Joynt Kumar, James I. McDaniel, Robert M. McGee, Harry G. Robinson III, Ann Stock, Gail Berry West

white house history quarterly

founding editor

William Seale (1939–2019)

editor

Marcia Mallet Anderson

editorial and production manager

Margaret Strolle

associate vice president of publishing

Lauren McGwin

senior editorial and production manager

editorial coordinator

Rebecca Durgin

consulting editor

Ann Hofstra Grogg

consulting design

Pentagram

editorial advisory

Bill Barker

Matthew Costello

Mac Keith Griswold

Scott Harris

Joel Kemelhor

Jessie Kratz

Rebecca Roberts

Lydia Barker Tederick

Bruce M. White

the editor wishes to thank The Office of the Curator, The White House

william g. allman is the former curator of the White House, having retired from the office in 2017 after forty years. He coauthored Something of Splendor: Decorative Arts from the White House, compiled the catalog of objects for The White House: Its Historic Furnishings and First Families, and contributed to The White House: An Historic Guide and the second edition of Official White House China: From the 18th to the 21st Centuries, and many other White House Historical Association publications.

thomas j. balcerski , a presidential historian, is associate professor of history at Eastern Connecticut State University. He is the author of Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King.

joy b. ferro is president of Elements for Success and is a consultant at the White House Historical Association. She specializes in project and event management in the United States and abroad. Ms. Ferro’s love of New York runs deep and is a self-proclaimed “native” New Yorker.

matt green is a former engineer who quit his job in 2010 to walk across the U.S.A. Since 2012 he has been walking every block of every street in New York City, a journey of more than 9,000 miles.

scott harris is the Executive Director of University of Mary Washington Museums and an editorial adviser for White House History Quarterly.

dean j. kotlowski is professor of history at Salisbury University. He has been a historical adviser to the National Archives, Richard Nixon Library, and U.S. Mint and has served four times as a Fulbright scholar. He is the author many books including the forthcoming Toward Self-Determination: Federal Indian Policy from Truman to Clinton.

kayli reneé rideout is a Ph.D. candidate in the American & New England Studies Program at Boston University. She studies American social history through decorative arts and material culture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

margaret strolle is an editorial and production manager at the White House Historical Association and a regular contributor to White House History Quarterly..

2

contributors

First Lady

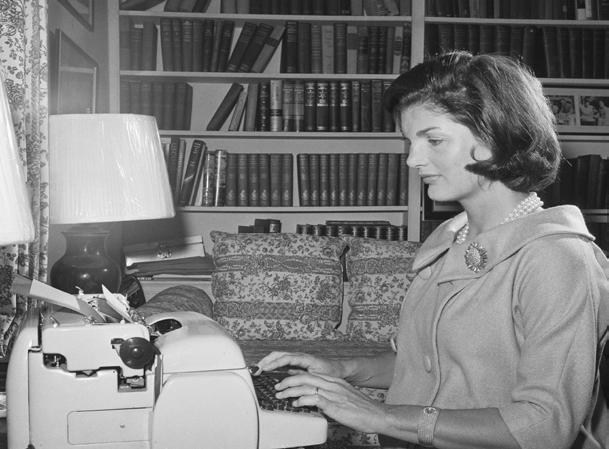

Jacqueline Kennedy accepts a gift for the White House Collection from Sears, Roebuck and

five

Native

Tiffany’s Associated Artists to Decorate the White House

84 NANCY REAGAN, THE BARBIZON, And a World Gone By

90

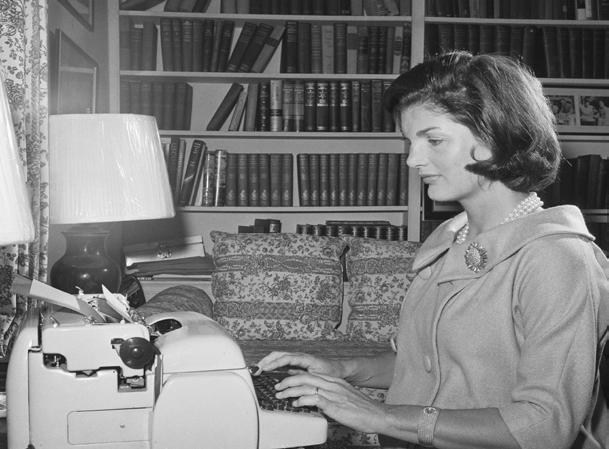

“HATS ARE THE MOST IMPORTANT THING”: Jacqueline Kennedy’s Letter to Bergdorf Goodman

margaret strolle

94

PRESIDENTIAL SITES FEATURE: Herbert Hoover, Apt. 31A, and U.S. Presidents at the Waldorf-Astoria

dean j. kotlowski

116 REFLECTIONS

stewart d. m c laurin

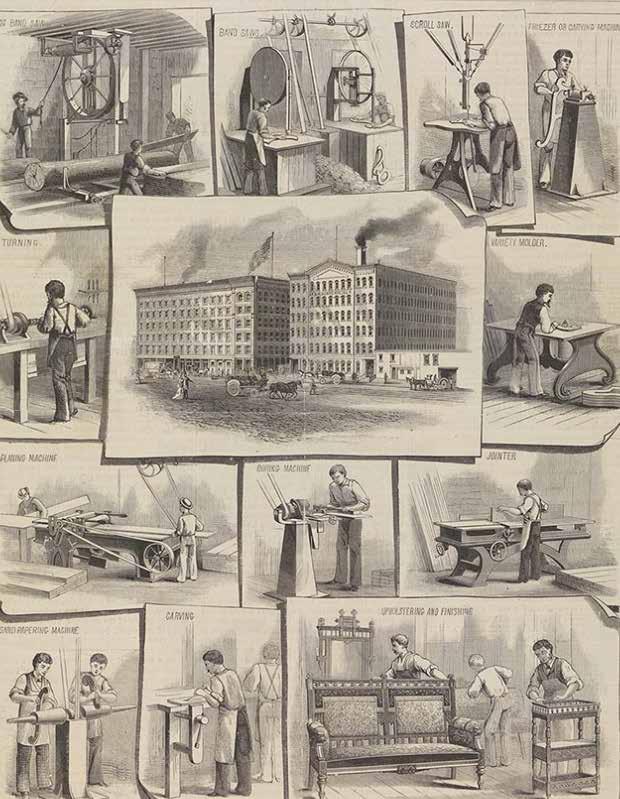

3 contents 4 FOREWORD marcia mallet anderson 6 STREET SCENES A New York Pedestrian’s Chance Encounters with Presidential History matt green 26 BEFORE THE WHITE HOUSE New York’s Capital Legacy thomas j. balcerski 38 THE NEW YORK CITY DEATH AND BURIAL of President James Monroe scott harris 52 MADE IN NEW YORK For the White House william g. allman 72 A TIFFANY WHITE HOUSE INTERLUDE: President Chester A. Arthur Commissions Louis Comfort

kayli reneé rideout

joy ferro

ALAMY

Company of

portraits of

Americans painted by Charles Bird King. The gift is presented by Sears vice president, James T. Griffin, who holds up a portrait of Chief Shaumonekusse of the Oto tribe, December 6, 1962.

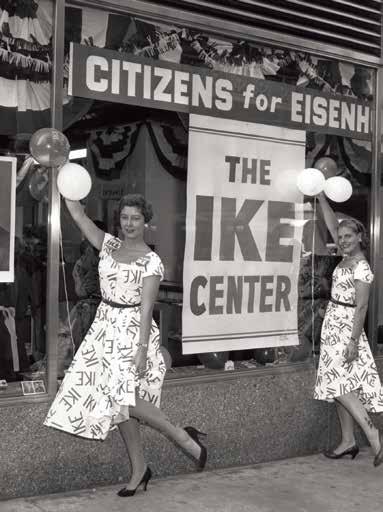

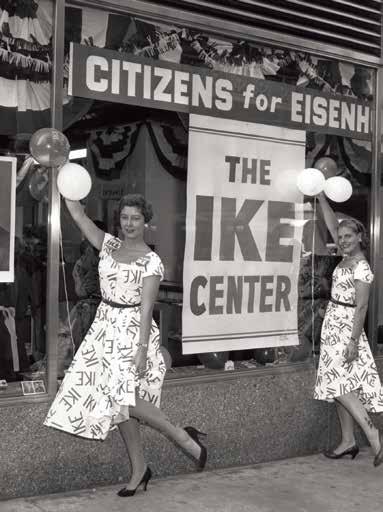

Only in New York

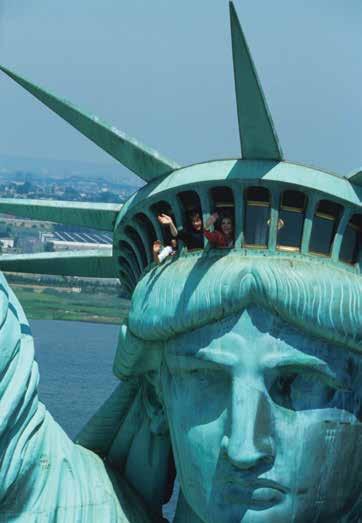

Before there was a 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, or even a City of Washington, some of the earliest chapters of White House history were written in New York City. George Washington took the first presidential Oath of Office at Federal Hall on Wall Street in 1789 and lived in the first presidential mansions on Cherry Street and on Broadway before the young federal government was moved to Philadelphia in 1790. For more than two centuries, New York City has welcomed, accommodated, celebrated, and mourned Washington’s successors. Though all of these later presidents would reside in the White House in Washington, D.C., the lives of many included consequential years in New York. In a city so rich in history, many landmarks have inevitably been lost to time, while others—still standing or at least identified by markers on newer buildings—offer moments in White House history to millions of passersby. With this issue, White House History Quarterly explores the historical connections between New York City and the White House from the first Oath of Office to the present day.

Our visit to New York opens with a journey expertly led by Matt Green, who since 2011 has walked more than 9,400 miles of the city, block by block, embracing countless chance encounters with presidential history along the way. “There’s a big difference between reading about a place in a book and being there in person,” he explains. “What it feels to stand in front of it, to touch it, to discover something about it—all of a sudden it comes alive to me.” Through Green’s expedition we, too, discover such easily overlooked places as the site where Chester A. Arthur took the Oath of Office and bodegas named for Barack Obama, as well as the four-hundred-year-old tulip tree that has witnessed it all.

With his article “Before the White House: New York’s Capital Legacy,” presidential historian Thomas Balcerski takes us back to the New York that President Washington knew and traces the legacy of the sites where he was inaugurated and lived.

“After traveling far and wide in life, James Monroe continued his odyssey in death,” explains historian Scott Harris with his article, which traces a series of temporary entombments that ultimately took the fifth president’s remains from New York to Virginia.

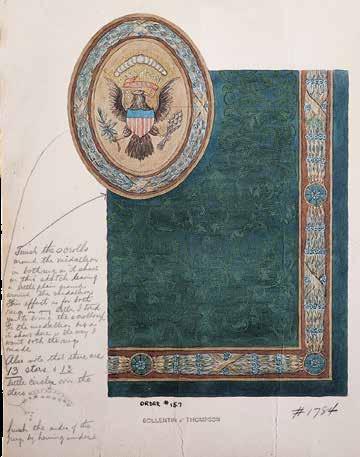

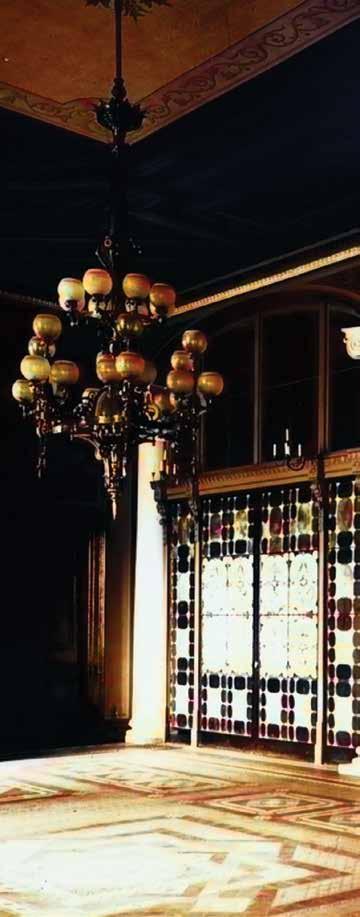

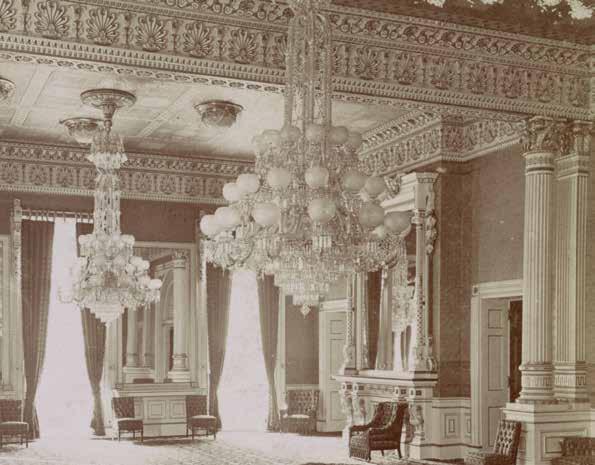

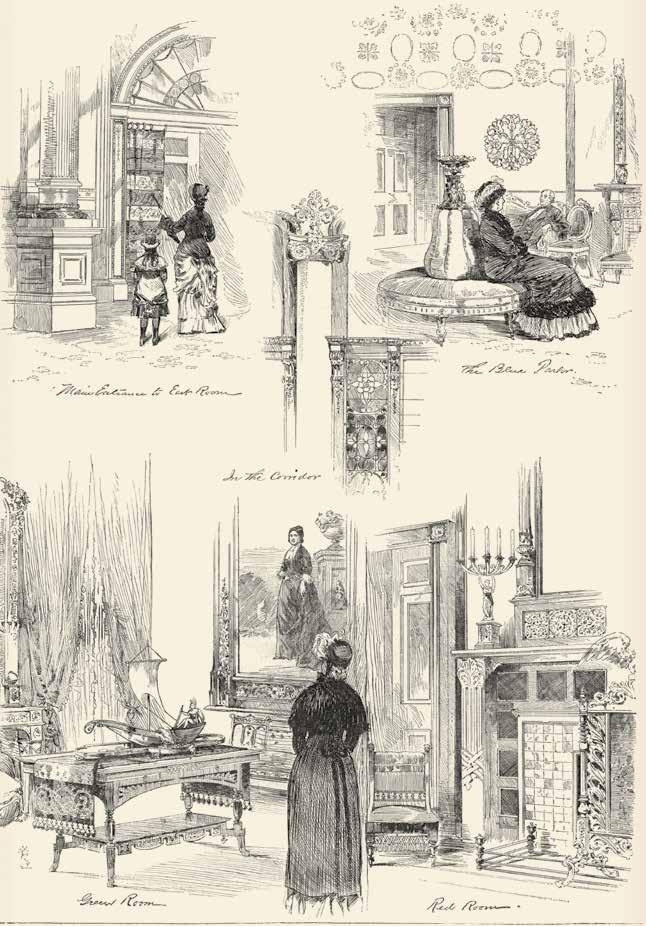

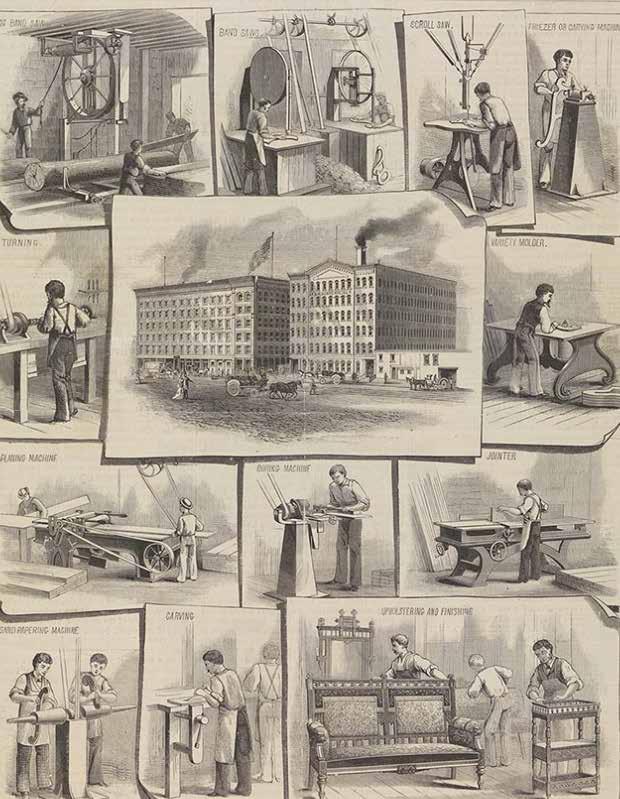

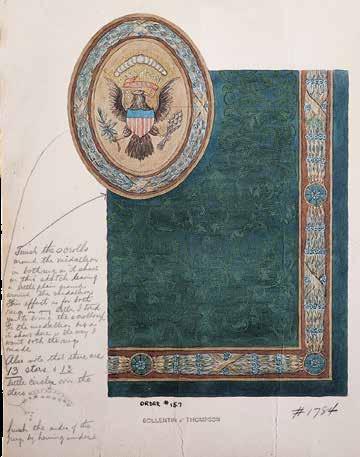

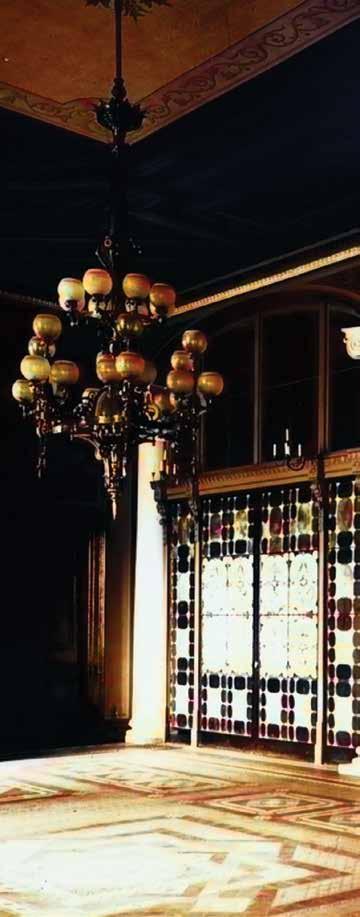

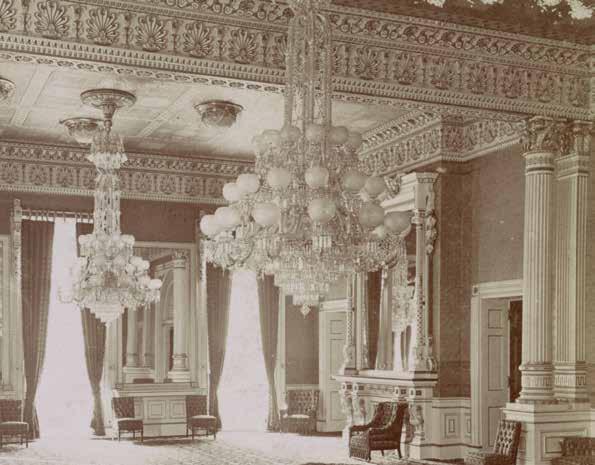

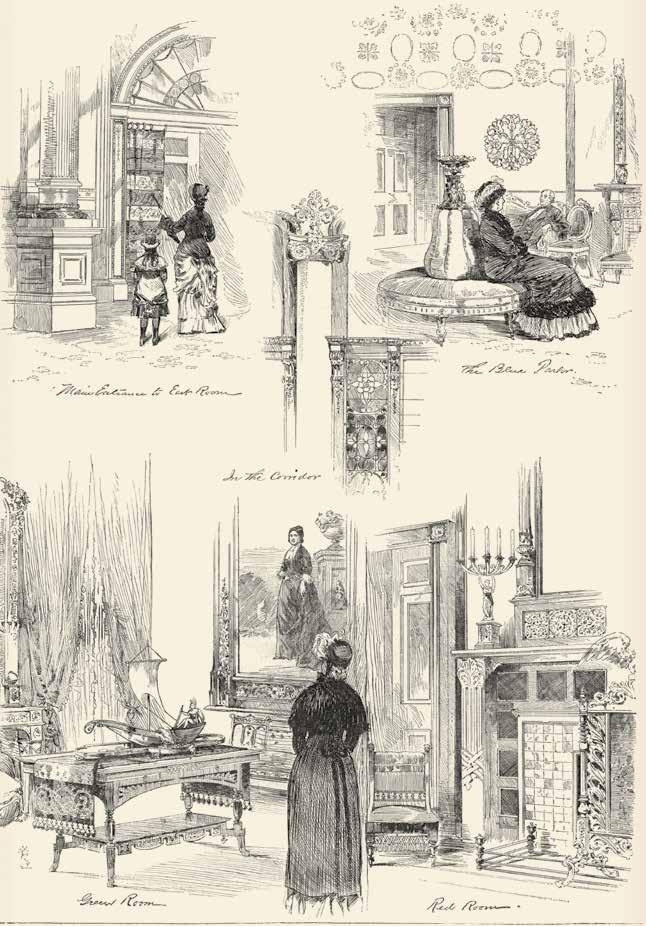

Former White House Curator William G. Allman presents the many New York manufacturers whose works are among the most treasured objects in the White House Collection of decorative arts today. Included are furniture by Charles-Honoré Lannuier and Duncan Phyfe, pianos by Steinway & Sons, silver by Tiffany, and lighting by Edward F. Caldwell. One of the most legendary of these New York businesses is the focus of Kayli Reneé Rideout’s article “A Tiffany White House Interlude.” Rideout explores President Arthur’s commission of Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Associated Artists to decorate the White House in 1881. Their once-celebrated decor of the State Floors would last for barely twenty years before succumbing to inevitable changes in taste. Yet interest in Tiffany’s longlost jewel-toned glass screen, which once transformed the White House Entrance Hall, has never faded.

Reminding us that America’s first ladies have long been connected to New York, author Joy Ferro, recounts the story of future first lady Nancy Reagan who, in the late 1940s, pursued her early dreams on the stage while living at the Barbizon, a safe and respectable residential hotel for women on the Upper East Side.

Author Margaret Strolle takes us to a display on the seventh floor of Bergdorf Goodman to study a letter written by Jacqueline Kennedy, one of many first ladies who turned to New York for fashion. Determined that every detail of her look be perfect, she requested a personal shopper to select hats and gloves to complete her wardrobe.

For our presidential sites feature in this issue, historian Dean Kotlowski takes us to the Waldorf-Astoria, which has welcomed the presidents and first ladies at political and social events for more than a century. His article “Herbert Hoover, Apt. 31A, and U.S. Presidents at the Waldorf-Astoria” recounts the retirement of President Hoover, who was comfortable there for more than twenty years.

The two centuries of the entwined history we have begun to explore with this issue is made up of at least as many stories, both large and small, as the number of blocks and miles Matt Green has walked. So we devote a few of the final pages of this issue to a photographic sampling of those smaller, fleeting, and “only in New York.”

4 foreword marcia

anderson

quarterly

mallet

editor, white house history

5 white house history quarterly SHUTTERSTOCK

Crowds begin to gather for a ceremony at a replica of the Federal Hall building reconstructed in Bryant Park 1932. Erected to celebrate George Washington’s one-hundredth birthday, the temporary structure was intended to recreate the site where Washington took the oath of office in 1789.

David

Could you make the words dark enough to be legible?

6

STREET SCENES:

A New York Pedestrian’s Chance Encounters with Presidential History

MATT GREEN

MATT GREEN

7 white house history quarterly

OPPOSITE: MATT GREEN / ABOVE: BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

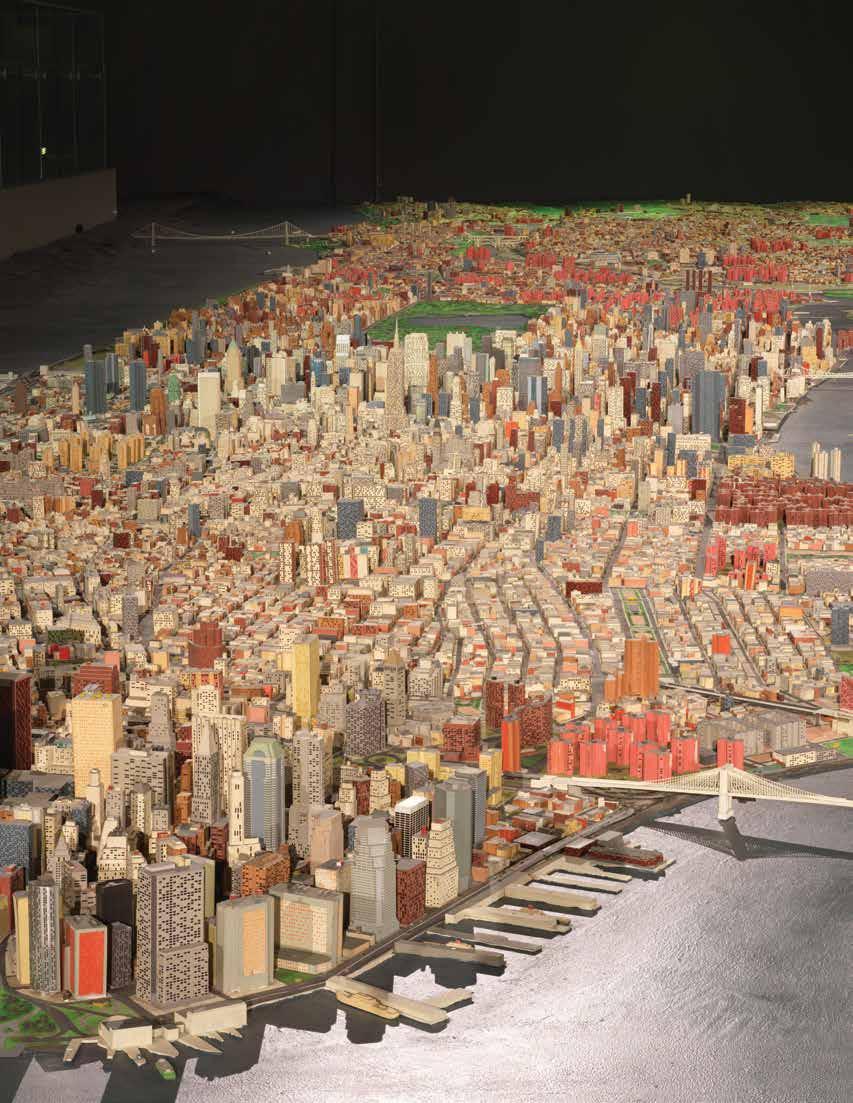

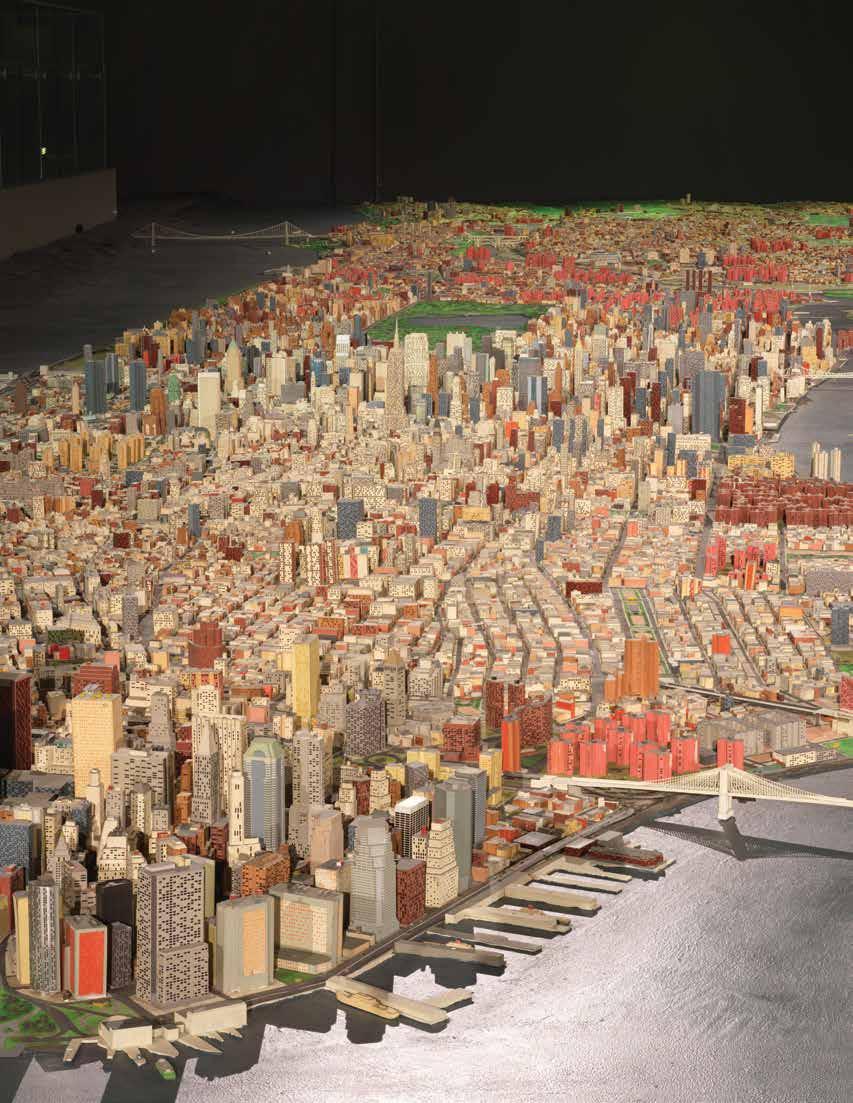

Matt’s ongoing walk of New York City will ultimately cover every street in the five boroughs: the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, and Staten Island. The boroughs are clearly illustrated in this map made in 1900, when Staten Island was still known as Richmond. Matt has been on his journey for more than eleven years and has covered over 9,400 miles.

8

GETTY IMAGES white house history quarterly

Matt’s years of walking every street in the five boroughs of New York began December 31, 2011. Blindfolded by friends, he was driven to Amboy Road in Staten Island, a randomly selected location, where he removed the blindfold and started walking.

Disembarking the big orange ferry after a ride across New York Harbor from Staten Island, a few friends and I start to make our way uptown from the southern tip of Manhattan. Unlike the modernist numbered thoroughfares that methodically divide most of Manhattan into tidy rectangular blocks, the narrow streets down in this part of the island evoke an older era. They bend and meander, tracing the routes of the first roads laid out here by Dutch colonists almost four hundred years ago. Nearby Wall Street gets its

name from the wooden wall that once stood along its path, a protective barrier built at what was then the northern edge of the settlement known as New Amsterdam. And Wall Street, in turn, has given this neighborhood its name: the Financial District. But even as the area has been thoroughly shaped by the relentless, unsentimental tide of capitalism, there remains a romantic sense of history hanging in the air.

The friends joining me on this walk are marking the first day of my multiyear quest to walk every block of every street in the five boroughs of New York City. Adding in parks, cemeteries, beaches, and various other public spaces, it will end up being a journey of more than 9,000 miles on foot, all within the bounds of a single city. I don’t know it at the time, but it will take me well over a decade to complete.

We had started the day at a randomly selected location, the 4300 block of Amboy Road in Staten Island. I didn’t even know where I was until the friends who had driven me there took off my blindfold. The plan was to get my bearings and map out a

9 MATT GREEN

DAY 1: December 31, 2011

white house history quarterly

10 BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION white house history quarterly

long walk to the ocean, celebrating New Year’s with a plunge in the chilly Atlantic. We decided to head north to the ferry and then across the bottom of Manhattan to the Brooklyn Bridge and on through Brooklyn to Brighton Beach. The 27 miles of blocks we’ll cover constitute just one puny little line on my progress map, the first tiny bite taken out of a truly immense apple.

A few blocks from the ferry terminal, at Broad and Pearl Streets, we pass Fraunces Tavern, a stout three-story brick building. The name is familiar to me—some kind of association with George Washington—but I’m not sure of the details.

Rather than read about the areas I’m going to walk ahead of time, I like to just walk, try my best to pay attention, and take lots of photographs. Then I research what I see afterward. I don’t know enough to decide what’s important beforehand; I just let things catch my eye and then I dig in from there. What I end up with is not a thorough, organized account of the city’s history but instead an idiosyncratic understanding that builds slowly and circuitously, often in unpredictable and oblique ways, as individual threads of discovery that seem insignificant on their own begin to weave a dense, tangled

web of connections across many years and miles. Which is a wordy way of explaining why it’s only later, after the day’s trek is done, that I read that Fraunces Tavern is where, not long after the final British troops left New York City in 1783 at the end of the Revolutionary War, General Washington bade a poignant farewell to an assemblage of officers of the Continental Army. One of those officers, Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge, penned his recollections some years later:

After the officers had taken a glass of wine General Washington said “I cannot come to each of you but shall feel obliged if each of you will come and take me by the hand.” General Knox being nearest to him turned to the Commander-in-chief who, suffused in tears, was incapable of utterance but grasped his hand when they embraced each other in silence. In the same affectionate manner every officer in the room marched up and parted with his general in chief. Such a scene of sorrow and weeping I had never before witnessed and fondly hope I may never be called to witness again.1

11 white house history quarterly

GETTY IMAGES

The landmarks Matt passed on his first day of walking every block in New York included Fraunces Tavern (seen opposite in 2023), where George Washington famously made a farewell toast to his officers at the end of the Revolutionary War. The colorful lithograph (above) depicting the moment was made by Nathaniel Currier in 1848.

DAY 30: January 29, 2012

experience. The ranch-style houses, the front yards, the trees planted along the sidewalks—all pleasant features of a lovely neighborhood but not the kinds of things that jump out and grab your attention as you pass by. But sometimes the wonder of a place’s present can be appreciated only in relation to its past.

A pedestrian could be forgiven for walking the three blocks of Charlotte Street in the South Bronx and coming away without a distinct memory of the

A pedestrian visiting Charlotte Street in 1977, for example, would likely have found the scene much more memorable, as Jimmy Carter discovered on an October morning of that year. A day after addressing the United Nations General Assembly on the subject of nuclear disarmament,2 President Carter headed uptown to witness firsthand the devastating urban decay that had ravaged the South Bronx. Iconic photos from his stop at Charlotte Street show him striding across vacant lots filled with rubble in what could be mistaken for

Matt’s walk in the South Bronx on Day 30 led him to Charlotte Street, an area also walked by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. What Carter found here was bleak—a dismal scene of urban decay. The area has since been so transformed that even the Bronx borough historian is not able to pinpoint the exact spot where this photograph of Carter’s visit was taken.

12 TERESA ZABALA/THE NEW YORK TIMES/REDUX

white house history quarterly

a bombed-out war zone.3 The Bronx borough historian, Lloyd Ultan, told the New York Times that he can’t even identify exactly where on Charlotte Street the photos were taken; there’s nothing that can serve as a landmark amid the utter desolation and emptiness.4

Today’s tranquil, ordinary Charlotte Street is a far cry from those dark days. It serves as a reminder of how quickly things can change when enough people with enough power decide a change needs to be made. But it also points to the lingering weight of stereotypes. Photos of the Bronx from the 1970s shape the public perception of the borough more than the modern-day reality does. And the reality, as you soon discover once you set foot there and say hi to a few folks, is that the Bronx, like everywhere else, is full of people who are exactly the same as

you, people trying to make a living, find love, care for their family, and do something meaningful with their time on earth.

I’m also struck by something else when I look at those photos of Jimmy Carter. I see a Georgia peanut farmer, fresh off grappling with the perils of international nuclear proliferation, now facing an overwhelming scene of urban despair here at home. The array of challenges facing anyone who dares to shoulder the weight of the presidency is so vast. It must be absolutely terrifying to take the Oath of Office and realize everything is now within your purview, all the struggles and anguish of an enormous nation in a tumultuous, ever-changing world. The ambition of anyone who could attempt such a thing is beyond me.

13 MATT GREEN white house history quarterly

The tranquil, treelined Charlotte Street that Matt photographed on a walk in 2012 bears no trace of the wreckage and rubble witnessed by Carter on his presidential visit.

Strolling through Manhattan’s East Village, passing a dense collection of row houses and apartment buildings on Second Street, I come upon a verdant enclave, a tiny cemetery occupying perhaps a quarter of a block. According to a sign on the fence, this is the New York City Marble Cemetery. It opened in 1831 and it’s the final resting place of a prominent merchant named Preserved Fish. I imagine him introducing himself at a party: “The name is Preserved Fish, but you can just call me Pickled Herring.”

As I later discover, the cemetery was also the notso-final resting place of an even more prominent figure: President James Monroe. After the death of his wife Elizabeth in 1830, he moved from his native Virginia to New York City to live with his daughter and her husband. He passed away the following year and was buried in the family vault of his son-in-law here at the cemetery.5 After twenty-seven years of peaceful repose, his remains were disinterred in 1858 and shipped to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, in grand style, a move initiated by Virginia’s governor, Henry A. Wise, as an expression of state pride.6 At Hollywood, President Monroe is entombed in a granite sarcophagus surrounded by an ornate cast-iron Gothic structure known to locals as “The Birdcage.”7

Another twenty-seven years after President Monroe’s departure, a new president would be laid to rest in New York City, this one for keeps. If you’re wondering who I’m talking about, you’ll just have to puzzle out the answer to the age-old riddle: Who is buried in Grant’s tomb?

New York City Marble Cemetery was for a time—from 1831 until 1858—the resting place of President James Monroe. Matt’s walk through the East Village on Day 98 took him past this tiny cemetery. Monroe is now buried in Richmond, Virginia, and is not mentioned on the plaque that hangs on the front gates. However, the wealthy merchant Preserved Fish (seen above c. 1830) made it into the posted history.

14 white house history quarterly LEFT: BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION / WIKIPEDIA

DAY 98: April 6, 2012

Unlike President Monroe, whose interment in New York was ultimately temporary, President Grant remains buried in Manhattan, in what is the largest mausoleum in North America. Matt’s walk took him to Grant’s Tomb on Day 1,941 (April 23, 2017).

15 white house history quarterly BOTH IMAGES: MATT GREEN

DAY 207: July 24, 2012

Heading down Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan, I pass under the Brooklyn Bridge, beneath a set of steel arches that support the roadway above. Chainlink construction fencing abounds, preventing curious passersby from getting a good look at the monumental stone anchorage of the bridge on either side of the street.

drawn to the south side of the street, to the rows of headstones in St. Peter’s Cemetery, the oldest Catholic cemetery on the island. But then I notice something unusual sticking out on the house-lined north side of the street: a large statue of a horse standing in a neatly planted bed of roses and shrubs.

After examining the sporty metallic equine, its muscles and veins visibly rippling beneath its skin, I turn my attention to the adjacent house. It’s much grander and older-looking than its neighbors, Greek revival in style with a quartet of two-story Corinthian columns supporting the roof of a stately portico.

Researching the house later on, I learn that one former resident was Julia Gardiner Tyler, the second wife and widow of John Tyler, who moved here to live with her mother after the former president passed away in 1862. While her husband may have had a fairly undistinguished run as president, he did establish a handful of firsts appreciated by trivia buffs. Following the death of William Henry Harrison, he became the first vice president to ascend to the highest office in the land without being elected, earning him the derisive nickname “His Accidency.” He was also the first president to

Matt’s Day 207 walk led him once again under the Brooklyn Bridge. This photo he took in 2022 shows how construction fencing blocks the view of the bridge’s monumental stone supports.

16

DAY 904: June 21, 2014

white house history quarterly

Walking along Tyler Avenue in the West Brighton neighborhood of Staten Island, my eye is initially

MATT GREEN

lose a spouse while in office, and became the first to get married in office when he and Julia tied the knot in 1844.

Despite hailing from New York State, Julia came to adopt the southern sympathies of her plantation-owning husband, whose casket was laid to rest in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, just a few years after James Monroe’s, draped not in the Stars and Stripes but in a Confederate flag.8 While living on Staten Island, Julia continued to advocate for southern causes during the Civil War. Two of her sons fought in the war on the Confederate side.9

And speaking of her offspring, here’s the most amazing bit of Tyler-related trivia that I find along the winding path of discovery that began with that odd horse statue: Julia and John have a living grandson. I repeat: John Tyler, who was born in 1790, has a living grandson, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, who is 94 years old.10 Harrison’s father, like his father before him, married a much younger woman after the death of his first wife, stretching out the generational timeline and making this astounding feat possible.11

17 white house history quarterly BOTH PHOTOGRAPHS: MATT GREEN

The widowed First Lady Julia Gardiner Tyler, a New York State native, lived in this grand Greek Revival house on Tyler Avenue in Staten Island following the death of President John Tyler in 1862. It was the nearby figure of a horse, so dramatically sculpted, that first drew Matt’s attention to the house on Day 904.

DAY 1,045: November 9, 2014

This ethnic career path was established the way so many others have been throughout time: A pioneer learns a specific trade and then teaches it to newer immigrants looking to establish a foothold in an unfamiliar country, in this case Afghans fleeing their homeland after the Soviet invasion began in 1979. The knowledge gets handed down over the generations, and, before you know it, and in a beautiful mishmash of cultures, you end up with an American city chock-full of Afghan-run chicken shops all named for a U.S. president who just so happened to share the first syllable of his last name with a certain American state featured prominently in the world’s most popular fried chicken brand.12

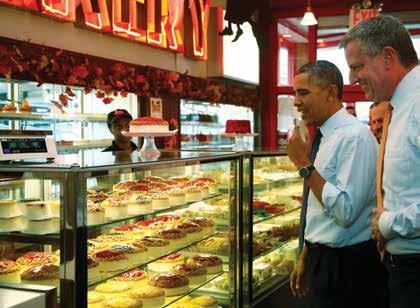

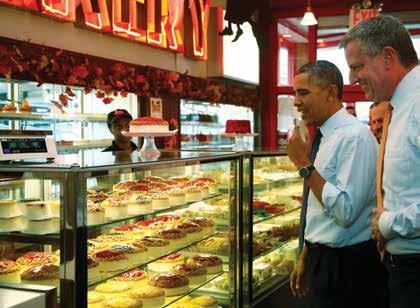

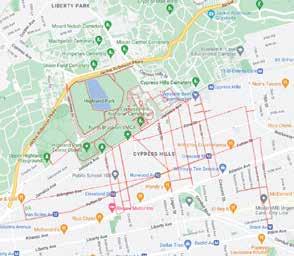

Barack Obama has a significant personal connection to New York City. He completed his undergraduate degree at Columbia University and spent a couple of years afterward living and working here. After all my walking, however, I’m starting to pick up on a different sort of relationship between the city and President Obama, one based not on residency but rather on the powerful symbolic quality of his presidency and the sense of possibility his election provided to many underrepresented communities. This relationship reveals itself little by little in the physical fabric of the city, expressed every now and again in a modest tribute like the name of a local business or a mural on the wall of a school.

But today, in Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills, I witness an unprecedented level of devotion to our forty-fourth president. I come across three different Obama-inspired bodega names within a seven-block stretch of Fulton Avenue: Obama Tobacco, Obama 44 Deli & Grocery, and King Barack Candy Store.

This brings to mind another memorable business name I encountered back in 2012 in Brownsville, Brooklyn: Obama Fried Chicken, a new addition to the proud New York tradition of presidential chicken. You can find a few Lincoln Fried Chicken shops around town, but the dominant player in this game is John F. Kennedy. There are dozens of Kennedy Fried Chicken joints cooking up birds all across the city. While they often have similar appearances and menus, the restaurants are generally run independently of each other and are largely owned and operated by Afghan immigrants.

18

white house history quarterly

MATT GREEN

Barack Obama, seen (above) walking to his car after arriving on Marine One at the Downtown Manhattan Heliport in 2010, attended college and worked in New York in the 1980s. The city’s affection for the president was evident in a seven-block stretch of Fulton Avenue Matt walked on Day 1,045, where three bodegas were named for him: Obama Tobacco (right), Obama 44 Deli & Grocery (above right), and King Barack Candy Store (opposite).

19 white house history quarterly TOP LEFT: WHITE HOUSE PHOTO / TOP RIGHT AND BOTTOM: MATT GREEN

President

DAY 1,364: September 24, 2015

The construction fencing beneath the Brooklyn Bridge at Pearl Street is still there, years after I first walked by, continuing to block public access to the bridge’s massive stone anchorage.

DAY 1,521: February 28, 2016

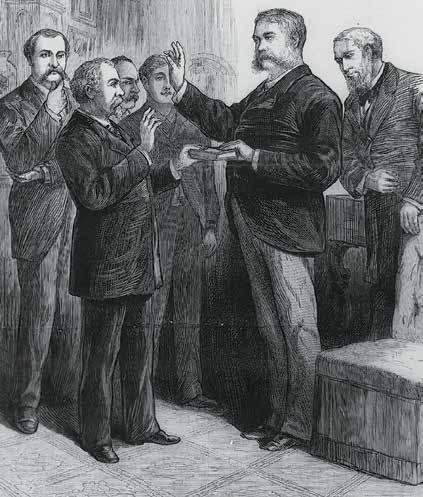

Making my way across Curry Hill in Manhattan, I stop at Kalustyan’s, the renowned spice and specialty food emporium that has been in business here at 123 Lexington Avenue since 1944. As much of an institution as the store has become, however, Kalustyan’s is not the most notable resident the building has ever had. That honor belongs to Chester Alan Arthur, who made a name for himself as a New York attorney before entering politics.

One significant case Arthur took on in his younger years was an 1854 lawsuit against the Third Avenue Railway Company filed on behalf of Elizabeth Jennings, who had been thrown off a streetcar on her way to church because she was Black. The successful suit paved the way for the eventual integration of all of the city’s public transportation in 1873.13 Elizabeth Jennings, whose place in history has long been overlooked, is now slated to be honored in the coming years with a statue in Manhattan commemorating her bravery and determination, part of a push to diversify the city’s collection of public statues, almost all of which depict males.14

Two notable sculptures of U.S. presidents have been taken down in New York in recent years amid this reconsideration of what our public art should be depicting and honoring. A statue of Thomas Jefferson was removed from the City Council chamber in 2021 because of his history as an enslaver of more than six hundred people during his life. And a statue of Theodore Roosevelt riding a horse and

flanked by a Native American man and a Black man on foot was removed from the entrance of the American Museum of Natural History in 2022 because of its depiction of the men as subservient to President Roosevelt.

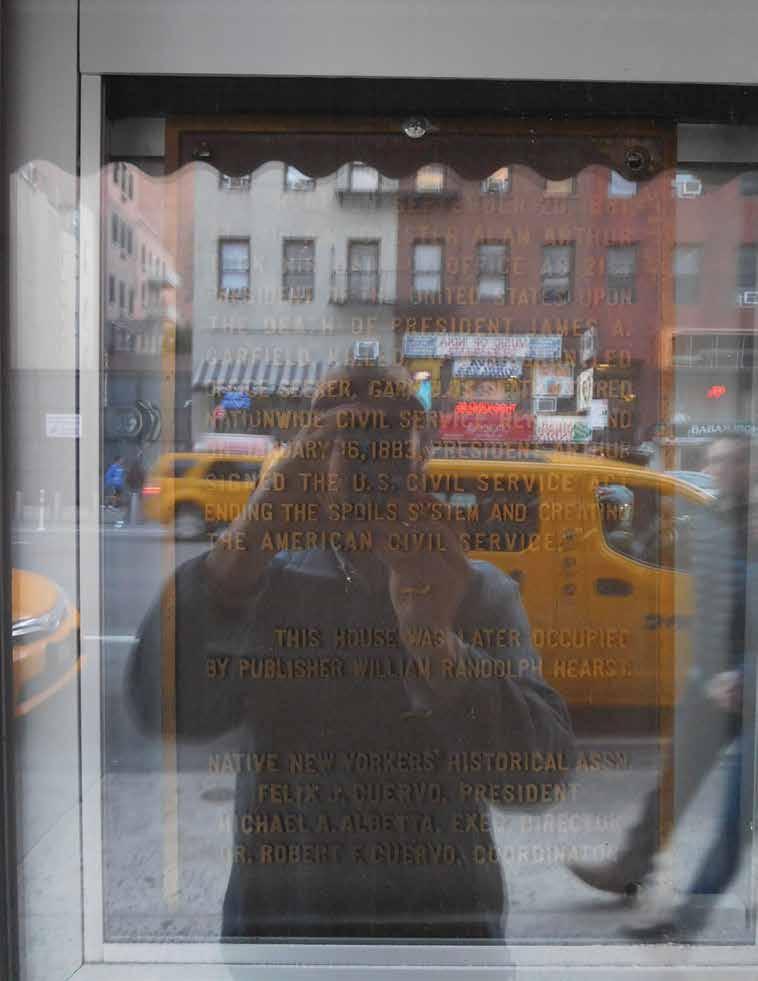

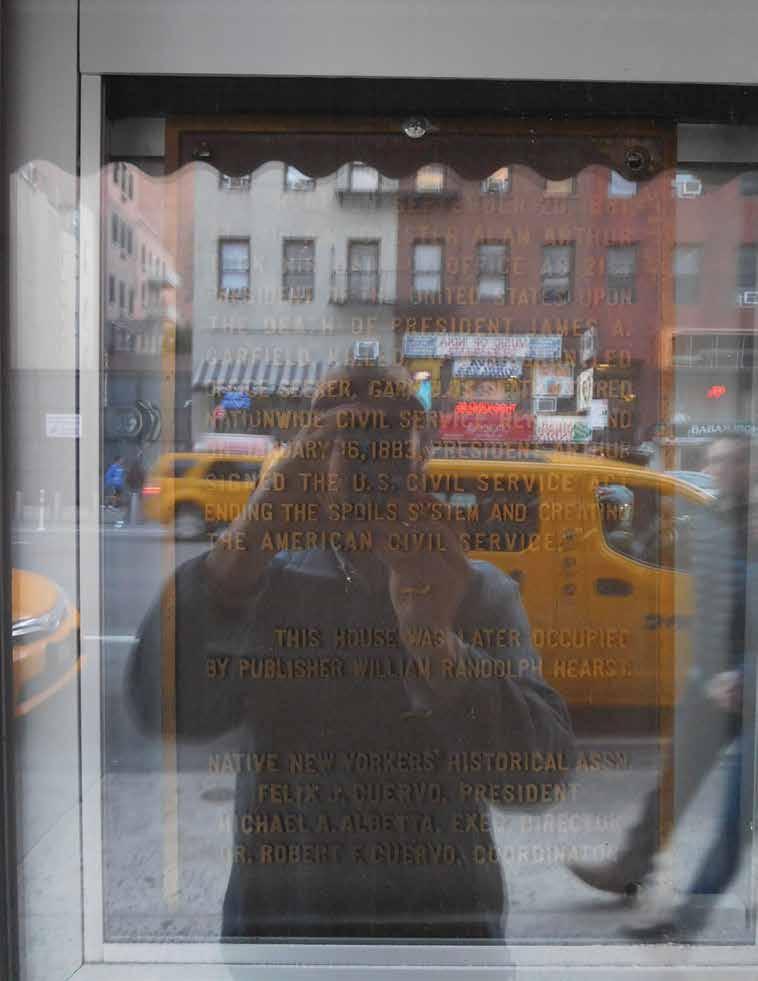

But let’s get back to 123 Lexington, which was the site of a very significant moment in presidential history, a moment whose memory is only tenuously carried into the modern day by an inconspicuous plaque mounted behind glass by the foyer door leading to the apartments above Kalustyan’s. The plaque reads, in part:

HERE ON SEPTEMBER 20, 1881, AT 2:15

A.M., CHESTER ALAN ARTHUR TOOK HIS OATH OF OFFICE AS 21st PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES UPON THE DEATH OF PRESIDENT JAMES A. GARFIELD, KILLED BY

A DISGRUNTLED OFFICE SEEKER.

A DISGRUNTLED OFFICE SEEKER.

On Day 1,521, Matt’s walk took him through President Chester A. Arthur’s old neighborhood, Curry Hill in Manhattan. It was at his home at 123 Lexington Avenue that Arthur took the presidential oath of office following the assassination of President James A. Garfield in 1881.

20

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS white house history quarterly

President Arthur might not recognize his old home on Lexington Avenue if he were to see it today. In his time (right), the entrance was on the second floor at the top of a short flight of stairs. Today, the building has been transformed to accommodate a storefront for Kalustyan’s (above), where spices have been sold since 1944.

David can you improve color?

This event made President Arthur the second, and to date last, president to take his Oath of Office in New York City. An imposing statue of George Washington standing outside the present-day Federal Hall on Wall Street very visibly calls attention to the location where our first president was sworn in, but the building where Chester Arthur assumed the duties of the presidency, a building that is still standing, unlike the Federal Hall of President Washington’s era, is all but invisible to the throngs of pedestrians passing by on the sidewalk every day.

21 TOP: MATT GREEN / BOTTOM: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION white house history quarterly

DAY 3,545: SEPTEMBER 13, 2021

More than nine years after I first walked under the Brooklyn Bridge on Pearl Street, the construction fencing is still standing and preventing the public from approaching the bridge’s stone anchorage. While there’s nothing in particular about the anchorage that would call out to someone walking by, I’ve learned over the years that surprising details and stories are hidden all over the city, and it’s not unusual for a seemingly pointless inspection of your surroundings to end up leading you somewhere you never expected.

DAY 3,800: May 26, 2022

I’ve been working on an article about my NYC walk and some of the presidential stories I’ve stumbled across along the way. While many presidents are woven into the fabric of the city in ways large and small, I’ve felt the presence of George Washington more than any other over the years. This makes sense, given that he led the Continental Army here during the early stages of the Revolutionary War and then served as president here during the brief period when New York was the nation’s capital.

As noted previously, the site of his swearing-in is prominently memorialized at Federal Hall, as you would expect. But, spurred on by the fact that this article I’m writing is for the White House History Quarterly, I realized I had no idea where George Washington lived during his time in New York. It seemed odd that I had never come across anything about his presidential residence—what would have essentially been our nation’s first White House.

What I learned is that he lived in two different presidential mansions during his time here, neither of which is still standing today. The first one was located at 1 Cherry Street (some say 3 Cherry Street), an address that ceased to exist when the Brooklyn Bridge was constructed on top of it. The only thing suggesting the symbolic importance of this location today is a brass tablet affixed to the bridge in 1899 by a chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

I had never noticed this tablet before. Being a plaque aficionado, my pride was a bit wounded when I learned I had overlooked it. After a little more digging around, I discovered the exact location of the marker: it’s mounted on the stone anchorage of the bridge on the south side of Pearl Street. For the entirety of my walk, more than a

decade now, this tablet has been hidden behind construction fencing.

So I head out to Pearl Street once again. Knowing precisely where to look now, I can see the brass tablet from outside the fencing, although it’s unreadable at this distance. While I’m gawking at the bridge, a grumpy construction worker passes through a gate in the fence and gruffly tells me I’m blocking his way. I start enthusiastically explaining why I’m here—America’s first White House! The most significant George Washington Slept Here of them all! But he completely ignores me and slams the gate in my face.

A minute later, another worker opens the gate. He’s much friendlier and politely listens as I explain, probably sounding like a fevered crackpot, that this is where the first president of the United States lived. I plead with him to let me step inside the fence for ten seconds so I can take a photo of the plaque. He apologizes and tells me he can’t allow me in, for liability reasons, but he offers to take my phone and snap a photo for me. A pretty good compromise! Our government could use more people like this guy.

22 WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION white house history quarterly

above

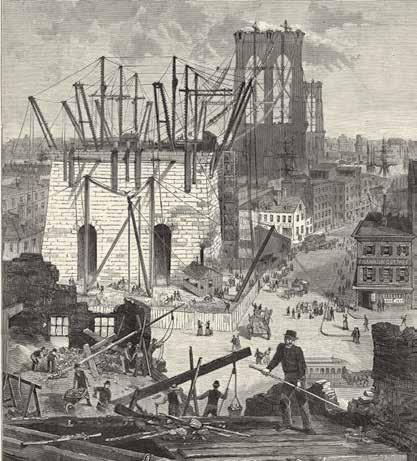

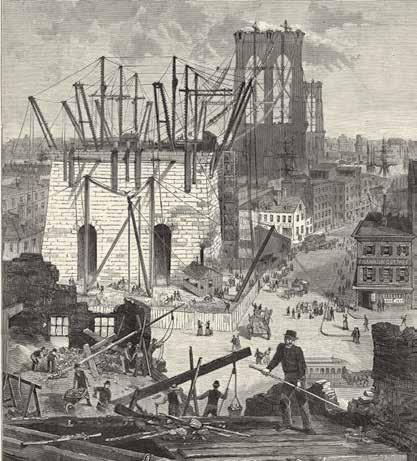

An illustration from 1877 shows how the site of the first presidential house came to be located under the Brooklyn Bridge. The image depicts the supports for the bridge rising above the surrounding buildings.

top

On Day 3,800, almost a decade after first passing the location, Matt finally spotted a brass tablet mounted on the stone anchorage supporting the Brooklyn Bridge. The plaque identifies the location of the first presidential mansion, George Washington’s home on Cherry Street. The tablet was installed by the Mary Washington Colonial Chapter in 1898, but construction barriers have made it inaccessible for the many years of Matt’s walk.

below

23 BOTH PHOTOGRAPHS: MATT GREEN white house history quarterly

This photo, taken for Matt by a construction worker, shows the nineteenth-century plaque marking the location of the first American presidential mansion.

24 white house history quarterly BOTH PHOTOGRAPHS THIS SPREAD: MATT GREEN

right

On Day 1,405, Matt crossed paths with President Washington again when he walked the service road of the Long Island Expressway. Along the route he photographed this plaque, which explains that Washington traveled the road on his tour of Long Island in 1790.

below

After crossing the Long Island Expressway and entering Alley Pond Park, Matt discovered the “Queens Giant,” a majestic, towering tulip poplar tree believed to be at least 400 years old. Matt was struck by the fact that it would have been standing tall when Washington visited the area himself. Today it is a living witness to the history Matt has encountered on his own journey through New York.

A FINAL REFLECTION

DAY 1,405: N ovember 4, 2015

I’m walking along the south service road of the notoriously traffic-clogged Long Island Expressway in Queens. When I reach the edge of Alley Pond Park, I look down and notice a bronze marker affixed to a boulder sitting beside the road. Placed there in 1934, it tells me that “George Washington traveled this road on his tour of Long Island, April 24th, 1790.” Imagining President Washington here conjures up an incongruous image of the presidential horsedrawn coach jammed in amid a million SUVs, stuck on the LIE in brutal rush-hour traffic, barely even moving at a crawl. George Washington Crept Here.

Enjoying the freedom of my bipedal propulsion, I cross over the LIE and head into the adjacent section of Alley Pond Park, looking for a mysterious creature known as the Queens Giant, a towering tulip tree that is thought to be the oldest living thing in New York City. But despite its soaring stature, it’s rather hard to find. Because it’s situated on a hillside, the shorter trees above it on the slope reach just as high into the sky and prevent it from sticking out noticeably.

After wandering through the woods for a bit, I finally come upon the Giant, identifiable by the chain-link fence ostensibly installed around the trunk to offer some protection to this ancient creature. But there’s a big hole cut in the fence and I duck in to take a closer look. I find a faded Parks Department information sign propped up against the base of the tree. The sign notes the Giant’s height (133.8 feet) and estimated age (400 years or more), and says that “it was standing tall when General George Washington passed close by in 1790 on a tour of Long Island,” offering a surprising resonance with the plaque I just saw beside the LIE.

Thinking about the sweep of history in New York can be a fairly abstract exercise. Even when I encounter a concrete physical link to the distant past in the form of a building or something else tangible, it’s tough for me to relate to the enormous expanse of time that has elapsed between that object’s creation and the moment when I find myself in its presence. I know it has existed all those years, but it’s done so in a kind of suspended animation that’s nothing like what a human being understands existence to be.

But the tree is something entirely different. I’m now standing next to and touching a being that

David can you make wording more legible?

hasn’t merely existed, but has actually been alive, since well before President Washington paid his visit to the area. The Giant has been spreading its roots for four centuries now, dating all the way back to when the first Dutch colonists set foot on the southern tip of an island then known to its native Lenape inhabitants as Mannahatta. This tree’s life is an unbroken chain of growth and breath, light and air, water and soil, bridging the vastness of time and connecting me to the past in a way I can viscerally feel.

NOTES

1. Quoted in “History,” Fraunces Tavern Museum website, www. frauncestavernmuseum.org.

2. Kathleen Teltsch, “Carter Says the U.S. Is Willing to Slash Atomic Arsenal 50%,” New York Times, October 5, 1977, A1.

3. Lee Dembart, “Carter Takes ‘Sobering’ Trip to South Bronx,” New York Times, October 6, 1977, A1.

4. Reported in Manny Fernandez, “In the Bronx, Blight Gave Way to Renewal,” New York Times, October 5, 2007.

5. “New York City Marble Cemetery: Landmark Designation,” March 4, 1969, New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission website, www.nycmc.org.

6. Parke Rouse, “Richmond Turned Out for Monroe Reburial,” Newport News (Va.) Daily Press, September 4, 1994.

7. “President James Monroe’s Tomb,” Hollywood Cemetery website, www.hollywoodcemetery.org.

8. “President John Tyler’s Monument,” Hollywood Cemetery website.

9. Christopher Gray, “Where a President’s Widow Backed the Confederacy,” New York Times, June 20, 1999, sec. 11, p. 7.

10. Robert D. McFadden, “Lyon Gardiner Tyler Jr., 95, Grandson of 10th President,” New York Times, October 8, 2020, B11.

11. Gillian Brockell, “The 10th President’s Last Surviving Grandson: A Bridge to the Nation’s Complicated Past,” Washington Post, November 29, 2020.

12. Steven Kurutz, “Chicken Little,” New York Times, August 15, 2004, sec. 14, p. 1.

13. Allison C. Meier, “The Woman Who Refused to Leave a WhitesOnly Streetcar,” JSTOR Daily, August 15, 2018, https://daily. jstor.org.

14. Julia Jacobs, “City Will Add 4 Statues of Women,” New York Times, March 7, 2019, A18.

25

white house history quarterly

Before the WHITE HOUSE

New York’s Capital Legacy

THOMAS J. BALCERSKI

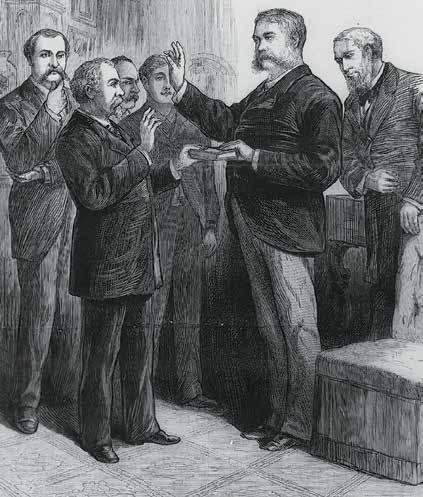

on april 30, 1789, George Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States of America. On the streets below, crowds gathered to witness Washington, his hand placed on a Bible, be sworn in from a balcony at Federal Hall in New York City. After taking the Oath of Office, Washington supposedly added the words “So help me God” and kissed the holy book. Following the ceremony Washington delivered an Inaugural Address to the members of Congress, then attended services at St. Paul’s Chapel. That evening fireworks illuminated the sky. The future of New York City—and the nation—never looked brighter.

27 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS white house history quarterly

It had been a long road getting to this point. Between 1775 and 1785, first the Continental Congress and then the Confederation Congress had met temporarily in seven different cities, namely Philadelphia, Baltimore, Lancaster, York, Princeton, Annapolis, and Trenton.2 Adding to its difficulties, Congress was sharply divided over the permanent home of the capital, split between those who wanted a central inland location and those who favored an established seaboard city.3

New York had been devastated by seven years of British occupation, including two great fires that had burned extensive swaths of the city in September 1776 and again in August 1778. But the city’s fortunes had slowly improved following the British evacuation on November 25, 1783 (a date celebrated for decades by the city’s residents as “Evacuation Day”), such that by 1790, the diverse population had grown to 40,000, of which 2,500 were enslaved people.4 In 1784, Chancellor Robert Livingston and the New York State Legislature beseeched the beleaguered Congress to select New

York as its next meeting place.5 Abandoning a plan to create two capitals, Congress voted unanimously on December 23, 1784, to relocate from the French Arms Tavern in Trenton to “the city of New York.”6

Once in New York, the outgoing Confederation Congress set about passing important legislation, including the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which provided for the organization of the Ohio country and notably excluded slavery from the territory.7 Congress also continued debating the relative merits of various sites for the permanent capital. In Philadelphia, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 failed to resolve the question and eventually voted to keep “the present Seat of Congress.”8

In September 1788, the Confederation Congress similarly voted to leave the seat of government in New York for the meeting of the new Congress, under the newly ratified Constitution, scheduled for March 4, 1789.9

New Yorkers eagerly prepared to celebrate the changeover to the new government. At midnight on March 3, thirteen cannons were fired from Fort

left

New

previous

28 NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY white house history quarterly

York’s City Hall on Wall Street, as first built with a Queen Anne facade in 1699.

spread George Washington stands on the balcony of Federal Hall as he takes the Oath of Office on April 30, 1789.

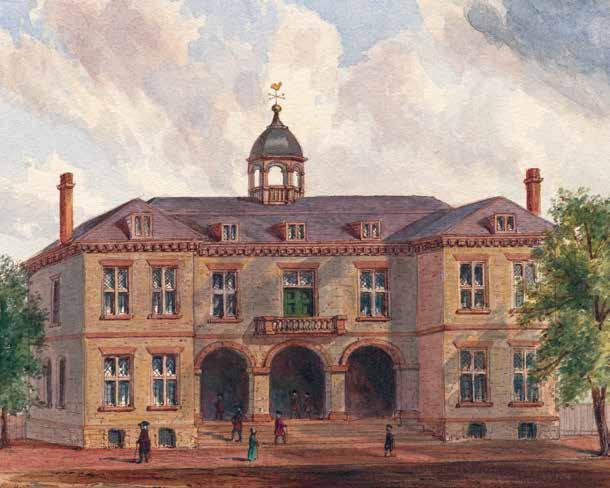

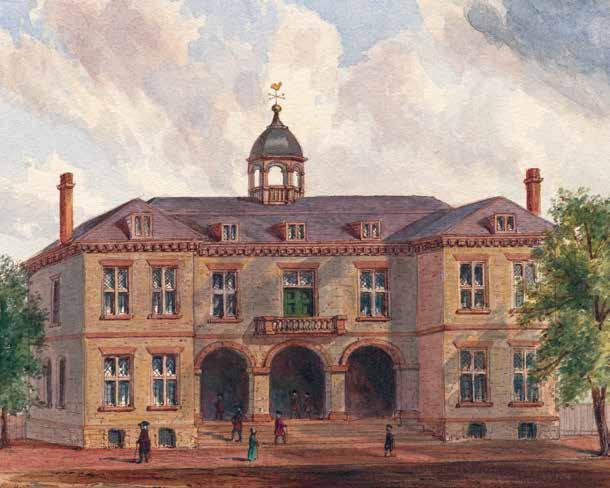

Given a neoclassical facelift by Pierre L’Enfant, City Hall is seen here as it appeared when George Washington stood on the balcony to take the first presidential oath of office.

George in salute of the thirteen states leaving the old confederation. The next day, flags were flown and church bells rang, but only eleven cannons fired in honor of those states that had already ratified the Constitution (North Carolina would not ratify the document until November, while Rhode Island held out until May 1790).10

New York had come to embrace its place as the nation’s capital.11 Previously, the Confederation Congress had been offered meeting space in City Hall as well as additional rooms at the tavern kept by Samuel (“Black Sam”) Fraunces at Broad and Pearl Streets.12 Then, on September 17, 1788, the Common Council of New York City resolved to give over City Hall for the exclusive use of the new federal government. The council commissioned Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the French émigré and

Continental Army soldier, to redesign the ancient building (constructed in 1700) into an edifice worthy of the seat of a republican government.13 Work began on October 6, 1788, and continued through April 8, 1790. L’Enfant’s efforts transformed the old Queen Anne facade by applying a neoclassical facelift, replete with an open balcony topped by a bald eagle. The impressive result left one congressman wondering if the building, now known as Federal Hall, was a “trap to catch the Southern men” into staying permanently in New York.14

But many questions remained about the future of the federal government. Most critically, when would George Washington, the newly elected president and “Father of His Country” arrive to take up his new office? And, perhaps equally as important, where would he live?

29 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

white house history quarterly

THE FIRST PRESIDENTIAL MANSION

When Congress convened in New York City, its members were expected to lodge in private residences, or boardinghouses, at their own expense.15 As a notable exception to this rule, the Confederation Congress provided furnished quarters for its president at the expense of the government. Since January 1788, the office had been filled by Cyrus Griffin of Virginia, who, following in his predecessor’s footsteps, lived at a large three-story home at No. 3 Cherry Street located about sixtenths of a mile from Federal Hall at St. George’s Square (later Franklin Square).16

The house was situated on land once owned by Robert Benson, who had previously operated a brewery on the site. In 1770, Benson’s widow, Catherine Van Borsum, and her son Robert Benson, sold the plot to merchant Walter Franklin for £2,000. Franklin built a Georgian– style structure on the site with a front face of about 50 feet. In 1786, Franklin’s widow, Maria Bowne Franklin, married Samuel Osgood, a commissioner of the treasury

whom Washington later appointed postmaster general. Accordingly, the home was variously known as the Walter Franklin House and the Samuel Osgood House.17

Nonetheless, George Washington was unclear just where he would stay as late as March 1789. Turning down an offer from New York governor George Clinton, Washington wrote James Madison on March 30 that he would “make it a point to take hired lodgings, or Rooms in a Tavern until some house can be provided.” Ultimately, he concluded, “it is my wish & intention to conform to the public desire and expectation, with respect to the style proper for the Chief Magistrate to live in.”18

Fortunately for Washington, Congress had turned its attention to the matter. On April 15, 1789, a joint committee of Congress—formed to plan the upcoming Inauguration—determined to renew the lease on the house at No. 3 Cherry Street for use by the new president. The committee resolved “That Mr. Osgood, the proprietor of the house lately occupied by the President of Congress, be requested to put the same house and furniture

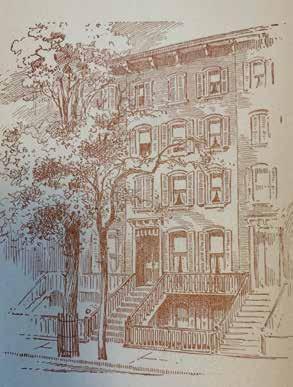

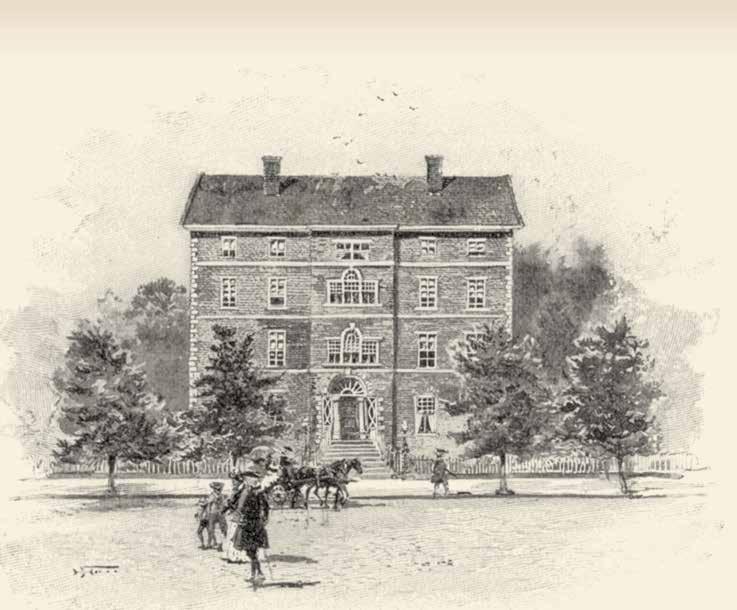

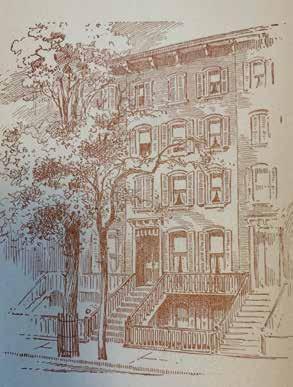

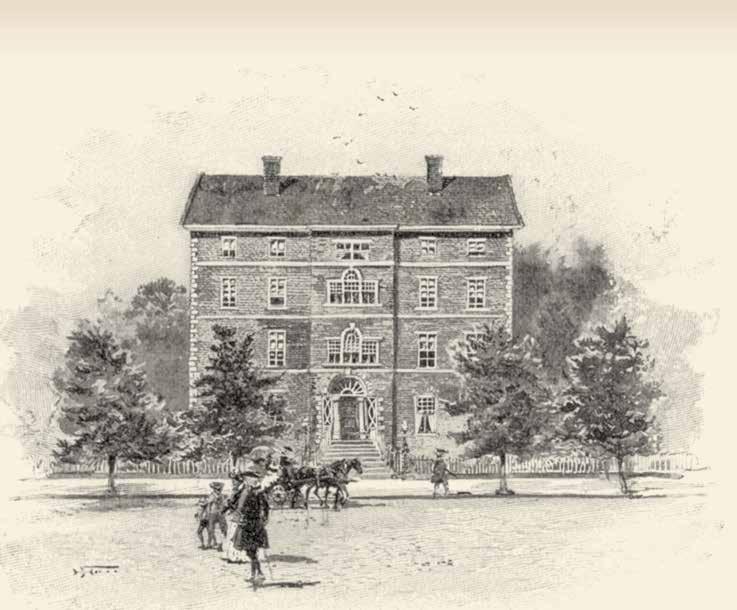

The first President’s House on Cherry Street, in Manhattan, as it appeared in 1800. President George Washington lived here from April 23, 1789 until February 23, 1790.

30 GETTY IMAGES

white house history quarterly

thereof in proper condition for the residence and use of the President of the United States.”19 The Franklin House—described by the French minister the Comte de Moustier as a “humble dwelling”—was leased for £845 a year, with another £8,000 expended to upgrade the home.20 Coincidentally, Washington’s next-door neighbor, at No. 5 Cherry Street, would be John Hancock, himself a former presiding officer of the Confederation Congress.21

Congressional absenteeism had been the culprit in the delay to secure a residence for the incoming president. On March 4, 1789, the day appointed by the Confederation Congress for the start of the new government, only eight senators and thirteen representatives were present. A quorum finally emerged in the House on April 1, while five days later, the Senate achieved numbers sufficient to count the electoral votes cast for president.22 The next morning, Charles Thompson, secretary of Congress, set out for Mount Vernon to inform Washington of his election as president of the United States, which he did on the morning of April 14.23

Washington immediately prepared to leave for New York. Short of funds, he borrowed some £625 from neighbor Richard Conway to pay his travel expenses.24 All along the route people came out to witness Washington pass by. On April 23, 1789, Washington crossed the Hudson River on a large barge and was greeted by a committee composed of Governor George Clinton, Mayor James Duane, and officers of the city’s governing corporation. An elaborate parade of military officers, troops, elected officials, clergy, and citizens accompanied the president approximately one mile from the Battery to No. 3 Cherry Street.25

New York society paid particular attention to president’s new house. As Sarah Osgood Robinson, niece of Maria Osgood, wrote to her friend Kitty Wistar:

Uncle Walter’s house in Cherry Street was taken for him [Washington], and every room furnished in the most elegant manner. Aunt Osgood and Lady [Catherine Alexander] Duer had the whole management of it. I went the morning before the General’s arrival to look at it. The best of furniture in every room, and the greatest quantity of plate and china I ever saw; the whole of the first and second stories is papered, and the floors covered with the richest

kind of Turkey and Wilton carpets. . . . There is scarcely anything talked about now but General Washington and the Palace.26

Not content with the furnishings at the Franklin House, Washington expended some £400 for glass and queensware and purchased bedsteads, chairs, knife boxes, washstands, clothespresses, and dining, tea, breakfast, and card tables.27 The efforts paid off, for upon her subsequent arrival Martha Washington found the house “handsomely furnished all new for the General.”28

The “Palace” was occupied by members of the Washington family and an array of household staff. Two Custis grandchildren—Eleanor (“Nelly”) Parke and George Washington (“Wash”) Parke—lived there. So did Tobias Lear, Washington’s personal secretary who supervised four additional secretaries, among them Thomas Nelson, nephew Robert Lewis, and political aide Colonel David Humphreys. Steward Samuel Fraunces oversaw a staff of white servants, which included a coachman, porter, cook, valet de chambre, maids, footmen, and laundresses.29

The Washington household also included seven enslaved African Americans from Mount Vernon: William (“Billy”) Lee, Washington’s longtime valet and body servant; Christopher Sheels, Lee’s nephew and later a body servant; Austin and Giles, both footmen; Paris, a stable hand; Molly, nursemaid to the Washington grandchildren; and Oney Judge, who later became famous for escaping from the president.30 Thus the staff of twenty-six outnumbered the four family members in residence at the Franklin House. It would be a pattern that carried over to future executive residences.

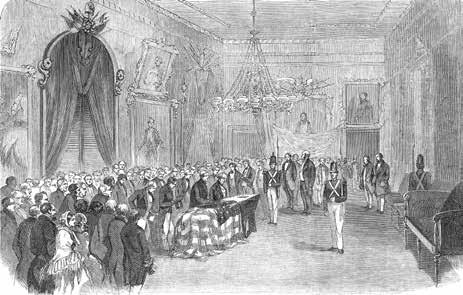

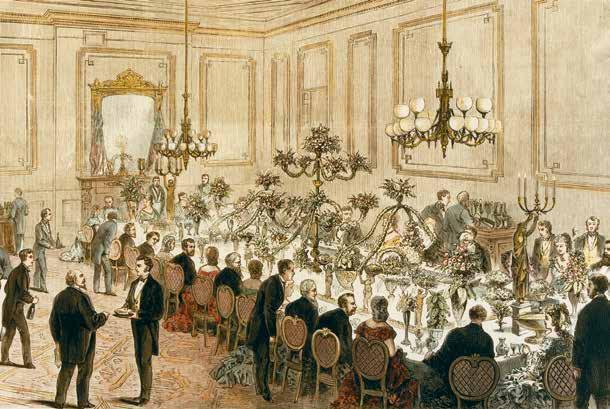

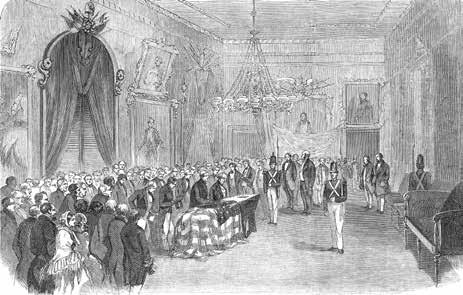

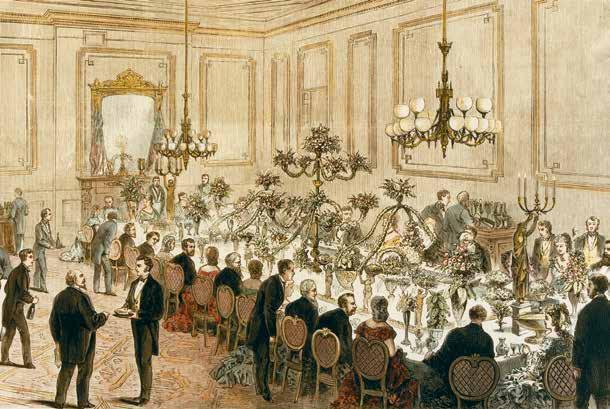

Even prior to settling his household, Washington participated in the first Inaugural Ball, called a “Public Ball and Entertainment.” The event had been pushed back by a week to allow for the arrival of Martha Washington, but when it became known that she would be delayed longer than expected, the ball went forward on May 7. With nearly three hundred people attending, all eyes were on the president, who danced two cotillions and a minuet. A week later, the French Minister de Moustier hosted a ball of his own.31

After Martha Washington arrived in the capital, she arranged a schedule of social events, most notably levees, dinners, and “drawing rooms” held each Friday from 7:00 until 9:00 in the evening.

31

white house history quarterly

George Washington attended the functions, without sword or hat, as he was in his capacity as the husband of the hostess and not as president of the United States.32 For its part, Congress voted after a prolonged debate that Washington be addressed simply as “the President of the United States,” without an additional title.33

President Washington also instituted the custom of holding “state dinners” each Thursday afternoon at 4:00 p.m. The gathering included “from ten to twenty-two” guests in addition to the president’s official “family,” which besides relatives included his secretarial staff. The meal tended toward “roast beef, veal, lamb, turkey, duck and varieties of game,” with silver-framed table ornaments adorned by “chaste mythological statuettes.”34 Beyond these formal social events, Washington also opened the house to the public twice per week on Tuesdays and Fridays, between 2:00 and 3:00 in the afternoon.35

Congress concluded its first session on September 29, 1789, with a strong record of legislative accomplishments, among them the introduction of amendments to the Constitution and the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1789.36 Hoping to strengthen the bonds of Union, Washington toured the New England states from October 15 to November 13, thus establishing regular travel as another function of the presidency.37 Washington’s first year at the Franklin House had proven a success. With the start of the new congressional session in January 1790, however, he determined to seize the first opportunity to upgrade the “Palace.”

THE SECOND PRESIDENTIAL MANSION

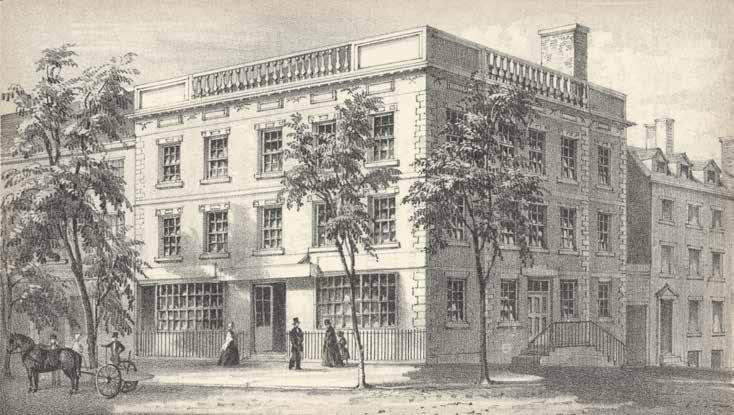

Washington’s chance came when French Minister de Moustier returned home, vacating his “fine and commodious mansion” at No. 39 Broadway.38 Built in 1786–87, it was owned by the merchant Alexander Macomb, who gladly offered it to Washington at an annual rent of £2,500; while more expensive than the Franklin House, it was a story higher and featured a garden extending to the banks of the Hudson River. The larger dining room could seat between sixteen and twenty guests.39 All in all, the Macomb House, or the “Mansion House” as the building later became known, was considered the “finest private dwelling in the city” and conveniently located four blocks from Federal Hall.40

On February 23, 1790, Washington and his family relocated to the Macomb House.41 Upon

agreeing to rent the house, Washington had surveyed the existing furniture and purchased several pieces left behind by de Moustier, including a writing desk and chair.42 From there, he arranged for the construction of a twelve-stall stable to accommodate his team of horses.43 In this way, Washington established another precedent, that of expanding the presidential residence to suit the occupant’s needs.

Hopeful about its possible future as the nation’s capital, New York City prepared to construct a permanent residence for the president. On March 16, 1790, the state legislature established a building commission and subsequently provided funding of £8,000 to build a grand house on the site of Fort George on Broadway. Dubbed “Government House,” the red brick colonnaded two-story structure attributed to builder James Robinson notably featured a front portico composed of Ionic columns. Yet Government House was never to fulfill its original purpose as the president’s home. The building was demolished in 1815 to make way for houses, before eventually being replaced by the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Customs House on Bowling Green in 1912.44

From the Macomb House, Washington settled into the duties of the Presidency. He began to call upon individual officers of the cabinet for advice, including Thomas Jefferson, who had recently returned from France. He paid special attention to the military and diplomatic aspects of the position, monitoring the army’s efforts in the Ohio country, and signing the nation’s first treaty with representatives from the Creek Nation.45 Washington was thus learning the extent of his executive powers.

Meanwhile, Congress continued to debate the future location of the capital. The political currents were running strongly against New York, with many favoring a return to Philadelphia.46 Dr. Benjamin Rush echoed the sentiments of others when he declared: “I rejoice in the prospect of Congress leaving New York; it is a sink of political vice. . . . Do as you please, but tear Congress away from New York in any way .” 47 William Maclay, another Pennsylvanian, similarly decried “the Pompous People of New York.”48 In addition, numerous smaller cities around the nation clamored to become the capital.49

At the same time, Congress had reached an impasse over the issue of assuming the states’ Revolutionary War debts. But on or about June 20,

32 TO COME white house history quarterly

Thomas Jefferson arranged for a dinner between James Madison and Alexander Hamilton at his rented house on 57 Maiden Lane. There Madison and Hamilton ironed out what has been dubbed the “dinner table bargain.” In exchange for assuming federal debts, the capital would be permanently located along the Potomac River. The resulting Residence Act of 1790 was passed on July 16. A month later, on August 12, Congress adjourned at New York City for the last time; until the new capital was ready, Philadelphia was to serve as the seat of government.50

The people of New York were “disappointed and vexed at the result.” A political cartoon blasted Pennsylvania delegate Robert Morris’s role in the

legislation. Perhaps not coincidentally, Washington occupied Morris’s Philadelphia mansion upon his arrival in the city.51 But the capital would not remain in Philadelphia for long, destined as it was for a new Federal District created on the banks of the Potomac River near Georgetown. On Saturday, November 1, 1800, President John Adams moved into the still unfinished White House. Two weeks later, on November 17, Congress met in Washington City for the first time.52 The nation had entered a new chapter.

33 white house history quarterly

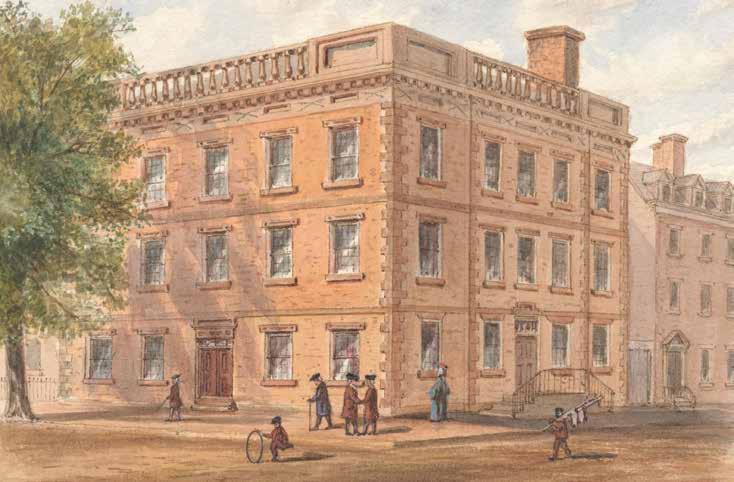

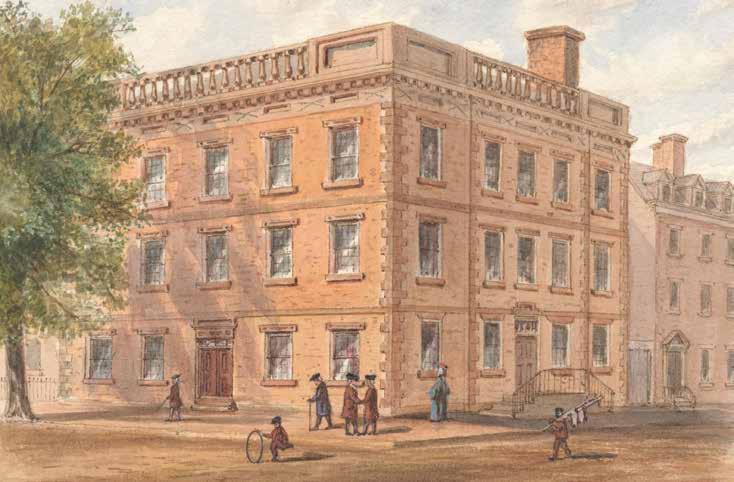

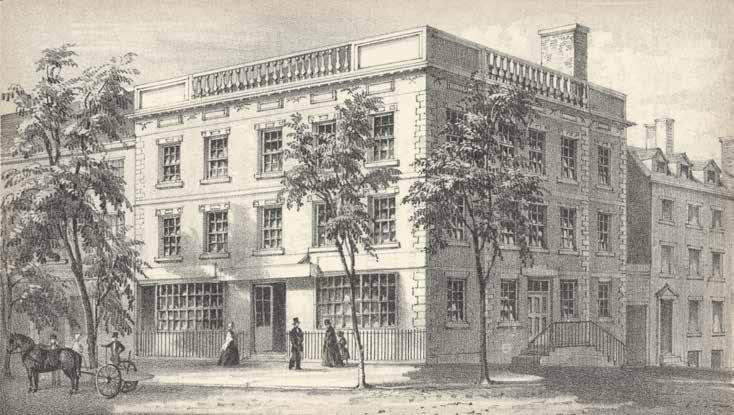

No. 39 Broadway, the second Presidential Mansion, was George Washington’s home from February 23, 1790, until August 1790, when the federal government relocated to Philadelphia.

THE FATE OF NEW YORK’S PRESIDENTIAL MANSIONS

What happened to the various buildings associated with President Washington’s time in the nation’s first capital? The Franklin House on Cherry Street transformed from a residence to a commercial property, remaining in the family’s hands until 1856 when it was demolished and replaced by stores. Benjamin R. Winthrop managed to obtain some of the original timbers for construction of what became known as “The Washington Chair,” now part of the collections of the New-York Historical Society.53 This subsequent building was demolished in the 1880s to make way for stone arches supporting the Brooklyn Bridge. A commemorative plaque provided by the Mary Washington Colonial Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution was installed on April 30, 1899. The plaque, which has itself become inaccessible and neglected, reads: “The First Presidential Mansion, No. 1 Cherry Street. Occupied by George Washington from April 23, 1789, to February 23, 1790.”54

The Macomb House has been similarly lost to time. In 1821 the building became a hotel, called Bunker’s Mansion House or Bunker’s Hotel, which operated for nearly three decades. The old house was apparently demolished to make way for

freestanding brownstone homes in the 1850s.55

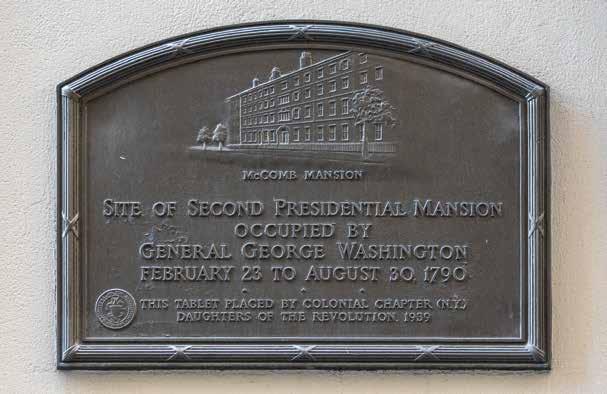

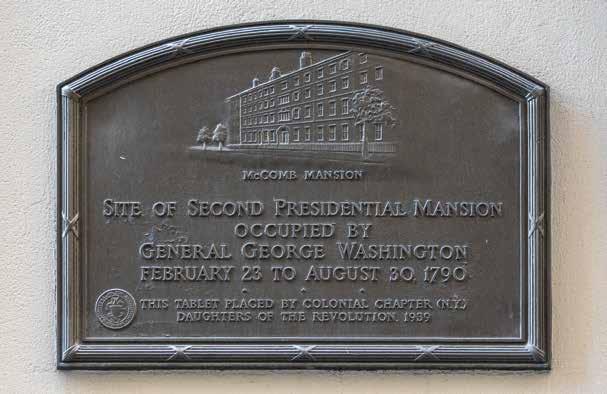

The brownstones were subsequently demolished in the early 1900s to make way for a neoclassical commercial building, which was torn down to erect the thirty-eight- story Harriman Building in 1926. In 1939, the Daughters of the American Revolution placed a plaque at the building’s base, reading: “Site of Second Presidential Mansion occupied by General George Washington February 23 to August 30, 1790.”56

The first Presidential Mansion, seen above in 1853, was converted from a residence into a commercial building and later demolished and replaced with stores. The location, now under the Brooklyn Bridge, is remembered with a plaque placed on the supports of the bridge in 1899.

34 TOP: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION white house history quarterly

The second Presidential Mansion, Washington’s home on Broadway, was converted into a hotel in 1821. Illustrated below in 1831, it was demolished in the 1850s. Today the Harriman Building, which has occupied the site since 1939, displays a plaque placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1939.

35 TOP: BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION BOTTOM: NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY white house history quarterly

THE LEGACY

The history of New York City’s time as the first seat of government is nearly all but forgotten, yet its capital legacy persists. Congress began to realize the full powers available to the new body. Through the passage of major legislation, Congress’s residence in New York demonstrated that it could cohere and was stronger than its predecessor. For the first time, it flexed the powers of the legislative branch of government that would in time shape the nation.

Similarly, George Washington’s year in New York City helped him in the ongoing process of inventing the presidency, both in its executive duties and symbolic functions. In New York, Washington established that the president should be regularly available to the public. Likewise, he set the precedent that a president should occasionally leave the capital to tour the country. Most significantly, Washington learned that the president’s residence should reflect the occupant’s place as the first citizen of a republican nation.

Despite fits and starts, the five and one-half year period when New York City was the capital set into motion great changes. There the old Confederation government ended, and the new federal government started. There Congress and the presidency both realized their real powers. And there, before the White House, stood the first two residential residences. Recalling New York’s capital legacy, then, reminds us of where the new American nation first took shape.

notes

1. For accounts of the events of April 30, 1789, see variously Stephen H. Browne, The First Inauguration: George Washington and the Invention of the Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 107–66; Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: Penguin, 2010), 565–71; Louise Durbin, Inaugural Cavalcade (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1971), 1–9; Frank Monaghan and Marvin Lowenthal, This Was New York: The Nation’s Capital in 1789 (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran, 1943), 262–83; William Loring Andrews, New York As Washington Knew It After the Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905), 45.

2. Robert Fortenbaugh, The Nine Capitals of the United States (York, Pa.: Maple Press, 1973).

3. Kenneth R. Bowling, The Creation of Washington, D.C.: The Idea and Location of the American Capital (Fairfax, Va.: George Mason University Press, 1991), 22–73; Bowling, “‘A Place to Which Tribute Is Brought’: The Contest for the Federal Capital in 1783,” Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives 8, no. 3 (Fall 1976): 129–40.

4. On New York’s wartime experience, see Edwin G. Burrow and Mike L. Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 245–61; Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 67. On the tradition of celebrating Evacuation Day, see Cornelius J. Foley, “History of the Celebration of Evacuation Day in New York City” (BA thesis, Queens College, 1967); Robert Goler, A Toast to Freedom: New

York Celebrates Evacuation Day (New York: Fraunces Tavern Museum, 1984). On New York’s population in 1790, see Robert I. Goler, “A Traveler’s Guide to Federal New York: Visual and Historical Perspectives,” in Federal New York: A Symposium, ed. Robert I. Goler (New York: Fraunces Tavern Museum, 1990), 7.

5. Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 43–63.

6. Ibid., 64. For the deliberations, see the minutes of December 23, 1784, in Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, ed. Worthington C. Ford, Gaillard Hunt, John C. Fitzpatrick, and Roscoe R. Hill (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904–37), 27: 699–704.

7. Peter S. Onuf, Statehood and Union: A History of the Northwest Ordinance (South Bend, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2019), 79–101.

8. Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 74–105, quotation on p. 96.

9. Harold T. Pinkett, “New York as the Temporary National Capital, 1875–1790: The Archival Heritage,” National Archives Accessions, no. 60 (December 1967): 1–12, esp. p. 7.

10. Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 104; Charles Bangs Bickford and Kenneth R. Bowling, Birth of the Nation: The First Federal Congress, 1789–1791 (Madison, Wis.: Madison House, 1989), 10; Monaghan and Lowenthal, This Was New York, 255.

11. Kenneth R. Bowling, “New York City: Capital of the United States, 1785–1790,” in World of the Founders: New York Communities in the Federal Period, ed. Stephen L. Schechter and Wendell Trip (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 1–23.

12. Pinkett, “New York as the Temporary National Capital,” 1–4.

13. Thomas E. V. Smith, The City of New York in the Year of Washington’s Inauguration, 1789 (New York: Anson D. F. Randolph, 1889), 40–44.

14. Quoted in Fergus M. Bordewich, The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016), 3. On the transformation of Federal Hall, see Fergus M. Bordewich, Washington: The Making of the American Capital (New York: Amistad, 2008), 11–13; Kenneth R. Bowling, Peter Charles L’Enfant: Vision, Honor and Male Friendship in the Early American Republic (Washington, D.C.: George Washington Libraries, 2002), 14–18.

15. Bowling, “New York City: Capital of the United States,” 8–13.

16. On the occupancy of past presidents of the Confederation Congress at No. 3 Cherry Street, see William A. Duer, Reminiscences of an Old Yorker (New York: W. L. Andrew, 1867), 68; Lila Herbert, The First American: His Homes and His Households (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1900), 86. See also Thomas P. Chorlton, The First American Republic, 1774–1789: The First Fourteen American Presidents (Bloomington, Ind.: Author House, 2012), 422. The numbering system used for Cherry Street also changed through the years, with the confusing result that the house originally at No. 3 Cherry Street has variously been labeled as No. 1 and No. 9.

17. For a description of the house, see Henry B. Hoffman, “President Washington’s Cherry Street Residence,” New-York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin 23, no. 3 (July 1939): 90–102. On the name change to Franklin Square, see Andrews, New York As Washington Knew It, 59.

18. George Washington to George Clinton, March 25, 1789, Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. W. W. Abbott, Dorothy Twohig, et al. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1983– ), 1:443–44; George Washington to James Madison, March 30, 1789, ibid., 1:464–65.

19. Annals of Congress, 1st Cong., 1st sess., 19–20.

20. On the bill presented to Congress by Osgood, see the detailed accounts in the Samuel Osgood Papers, 1775–1812, New-York Historical Society, New York, and for reactions, see William Maclay, journal, September 26, 1789, Journal of William Maclay: United States Senator from Pennsylvania, 1789–1791, ed. Edgar S. Maclay (New York: D. Appleton, 1890), 166. For the description of the house as a “humble dwelling,” see Herbert, First American, 45.

36 white house history quarterly

21. Walter Barrett, The Old Merchants of New York (New York: Carleton, 1862), 300.

22. Charlene Bangs Bickford, “‘Public Attention Is Very Much Fixed on the Proceedings of the New Congress’: The First Federal Congress Organizes Itself,” in Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress, ed. Kenneth R. Bowling and Donald R. Kennon (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1999), 139, 141, 159–60.

23. Smith, City of New York, 214–18.

24. George Washington to Richard Conway, March 6, 1789, Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. Abbott, Twohig, et al., 1:368–69.

25. On Washington’s journey to and arrival in New York, see Bickford and Bowling, Birth of the Nation, 25; Monaghan and Lowenthal, This Was New York, 259-60; “An ‘August Spectacle,” Federal Gazette, and Philadelphia Evening Post, April 20, 1789, in A Great and Good Man: George Washington in the Eyes of His Contemporaries, ed. John P. Kaminski and Jill Adair McCaughan (Madison, Wis.: Madison House, 1989), 104–05.

26. Sarah Robinson to Kitty F. Wistar, April 30, 1789, in James G. Wilson, The Memorial History of the City of New-York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892 (New York: New-York History Company, 1893), 3:52. The term “Presidential Palace” was later used by Pierre Charles L’Enfant, among others, to describe what became the White House. Russell L. Mahan, “Political Architecture: The Building of the President’s House,” in A Social History of the First Family and the President’s House, ed. Robert P. Watson (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2004), 39–40.

27. John Riley, “Rules of Engagement: Ceremony and the First Presidential Household,” White House History, no. 6 (Fall 1999): 14–25, esp. p. 17.

28. Martha Washington to Fanny Bassett Washington, June 8, 1789, in Stephen Decatur Jr., Private Affairs of George Washington: From the Records and Accounts of Tobias Lear, Esquire, His Secretary (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1933), 21. See also Joseph E. Fields, ed., Worthy Partner: The Papers of Martha Washington (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994), 215–16.

29. For George Washington Parke Custis’s recollections of the house at Cherry Street, see Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington by His Adopted Son, George Washington Parke Custis, ed. Benson Lossing (New York: Derby & Jackson, 1860), 394–432; and Custis’s earlier account in “The Birth-day of Washington,” Washington Daily National Intelligencer, February 22, 1847. See also John Riley, “The First Family in New York,” Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association Annual Report (1989): 19–21; Riley, “Rules of Engagement,” 18.

30. Jesse J. Holland, The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House (Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, 2016), 11–37; Erica Armstrong Dunbar, Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (New York: Atria, 2017), 17–48. The enslaved people who accompanied the president in public were outfitted in livery consisting of a three-piece suit with stitching depicting Washington’s coat of arms.

31. Andrews, New York As Washington Knew It, 46–50.

32. Herbert, First American, 54–55.

33. Bickford, “‘Public Attention Is Very Much Fixed,” 162.

34. Herbert, First American, 48–51.

35. Jared Sparks, The Life of George Washington (Boston: Ferdinand Andrews, 1839), 413.

36. Bordewich, First Congress, 12–14.

37. T. H. Breen, George Washington’s Journey (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016), 159–206.

38. Andrews, New York As Washington Knew It, 59–60.

39. On the Macomb House, see Agnes Miller, “The Macomb House: Presidential Mansion,” Michigan History 37 (December 1953): 373–84. On the larger dining room, see Decatur, Private Affairs of George Washington, 126. Decatur placed the rent at $1,000 (p. 147).

40. Herbert, First American, 62.

41. George Washington, diary, February 23, 1790, Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976–79), 6:37.

42. For the full inventory of items purchased, see “Invoice: Articles Purchased by the President of the United States from Monsr. Le

Prince Agent for the Count de Moustiers, 1790 March,” George Washington Collection, Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington, Mount Vernon, Va.

43. George Washington, diary, February 3, 1790, in Diaries of George Washington, ed. Jackson and Twohig, 6:27–28.

44. For the legislation establishing Government House, see the entries for March 16, 1790, in New York Senate and Assembly, Journals (New York: State of New York, 1790). For the description of Government House, see John Drayton, Letters Written During a Tour Through the Northern and Eastern States (Charleston, S.C.: Harrison and Bowen, 1794), 83. See also William Seale, “Where the Chief Was Never Hailed: Rivals to the White House in 18th-Century New York and Philadelphia,” White House History, no. 6 (Fall 1999): 26–33. On the design and subsequent fate of Government House, see Damie Stillman, “Six Houses for the President,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 129, no. 4 (October 2005): 411–31; Donald Martin Reynolds, The Architecture of New York City: Histories and Views of Important Structures, Sites, and Symbols (Revised Edition) (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994), 252–64.

45. Lindsay M. Chervinsky, The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020), 126–62; J. Leitch Wright Jr., “CreekAmerican Treaty of 1790: Alexander McGillivray and the Diplomacy of the Old Southwest,” Georgia Historical Quarterly, 51, no. 4 (December 1967): 379–400.

46. Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 127–81.

47. Benjamin Rush to Peter Muhlenberg, c. 1790, quoted in Henry A. Muhlenberg, The Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg: Of the Revolutionary Army (Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1849), 319–20.

48. William Maclay, diary, June 11, 1789, The Diary of William Maclay and Other Notes on Senate Debate, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, ed. Kenneth R. Bowling and Helen E. Veit (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), 74.

49. Kenneth R. Bowling, “Neither in a Wigwam Nor the Wilderness: Competitors for the Federal City, 1787–1790,” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives 20, no. 3 (Fall 1988): 143–62.

50. On the events of the summer of 1790, see Bordewich, Washington, 31–52; Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 182–207; Kenneth R. Bowling, Politics in the First Congress, 1789–1791 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1990).

51. Griswold, Republican Court, (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1868), 234–38 (quoted 234). On Washington’s residence in Philadelphia, see Edward Lawler Jr., “The President’s House in Philadelphia: The Rediscovery of a Lost Landmark,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 126, no. 1 (January 2002): 5–95.

52. William Seale, The President’s House: A History, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2008), 1:38–79.

53. On “The Washington Chair,” see Benjamin R. Winthrop, The Washington Chair Presented to the New York Historical Society (New York: Charles B. Richardson, 1857). On the demolition of the Walter Franklin House, see the account in “The First Presidential Residence,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 7, 1856, 413–14.

54. On the installation of and subsequent fate of the plaque, see “A Historic Home Marked,” New York Times, May 2, 1899; Bernard Stamler, “Marking ‘White House’ No. 1,” New York Times, November 1, 1998. See also Matt Green, “Street Scenes: A New York Pedestrian’s Chance Encounters with Presidential History,” in this issue.

55. D. T. Valentine, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York for 1855 (New York: McSpedon & Baker, 1855), 582–83; Cromwell Childe, Old New York Downtown (privately printed, 1901), 19.

56. For the history of the site at 39 Broadway, see Molly Rockwold, “Architectural Review of 35–39 Broadway/11–15 Trinity Place: The Harriman Building” (unpublished paper, May 2016), 1–14. On the plaque, see Miller, “Macomb House,” 384.

37 white house history quarterly

The New York City DEATH AND BURIAL OF President James Monroe

SCOTT HARRIS

SCOTT HARRIS

39 OPPOSITE: BRUCE WHITE FOR THE WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION TOP: WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION white house history quarterly

james monroe undertook many long and eventful journeys throughout his seventy-three-year life. He crisscrossed the north ern colonies from 1775 to 1778 with the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. While serving as a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress from 1783 to 1786, he explored largely unsettled frontier territory in the Old Northwest. He made two round trips across the Atlantic in the 1790s and early 1800s for diplomatic assignments in France, Great Britain, and Spain. As president of the United States, Monroe undertook three extensive tours of the country: to northern states in 1817, the Chesapeake region in 1818, and the South in 1819.

After traveling far and wide in life, James Monroe continued his odyssey in death—first on a brief and somewhat confusing shuttle between two New York City cemeteries with almost identical names, and finally back to Richmond, the capital of his native state, Virginia. Monroe’s postmortem journeys occurred within an atmosphere of public veneration tinged with commercial and political exploitation.

MONROE’S NEW YORK BURIALS