12 minute read

Newsworthy Welcomes

New York’s Waldorf-Astoria has welcomed presidents, first ladies, and those close to the presidents at political and social events for more than a century.

Clockwise from top right: President Franklin D. Roosevelt speaks at [event to come]; Former President Harry S. Truman cuts his birthday cake at a dinner given by the Harry S. Truman Library Committee, 1954; President John F. Kennedy addresses the annual dinner of the Bureau of Advertising of the American Newspaper Publishers Association, 1961; and President Lyndon B. Johnson speaks to guests at the Weizmann Award dinner, 1964.

A Second And Then A Permanent Home For Herbert Hoover

Hoover and the Waldorf were a matched set. “He loved the Waldorf,” recalled Joseph P. Binns, the hotel’s manager during the 1950s.13 It became home to this much-traveled, once-admired, and later reviled leader. Hoover found the Waldorf’s management personally and ideologically congenial. The staff and the surroundings provided comfort and support as he endeavored to regain his political influence and revive his reputation. Hoover’s relationship to the Waldorf was more private than public, at least when compared to the presidents, first ladies, presidential aspirants, and assorted politicians who came to the hotel to speak, attend a meeting, share a meal or drink, and then depart. Yet, for Hoover, private and public affairs merged. He worked from his apartment, writing books, conferring with VIPs, and seldom dining alone. His later life revealed a man both formal and humble—someone accustomed to the national limelight and the finer points of life, yet loath to sit still. From the Waldorf, Hoover campaigned, not for votes or office, but for a better country that would think better of him.

Herbert Hoover was always on the move. He ascended from an orphaned childhood in Iowa to the presidency. In between, he graduated from Stanford University; plied his expertise into a lucrative career in mining and business; lived in Australia, China, and London; oversaw international relief for war-ravaged Belgium; ran Woodrow Wilson’s wartime U.S. Food Administration; and headed the Department of Commerce under Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge. Portrayed as a policy wunderkind (and wonk), adept problem solver, and moderate reformer, he won the White House in a landslide. Yet the Great Depression shattered Hoover’s presidency, and his harsh expulsion of the Bonus Army from Washington, D.C., ended his reelection prospects. Hoover’s reputation never fully recovered. Many Americans resented him for failing to provide adequate relief for unemployed people and a solution to America’s worst economic crisis. Under Hoover, one person vented, “We nearly starved. Only the bark off of the trees was left.”14

Rehabilitation and respite became Hoover’s priorities throughout a restive retirement. An observer once noted: “The days, weeks or months were not long enough for Hoover to work.”15 Yet thoughts of a political comeback in 1936 and 1940 went nowhere, and Hoover’s attacks on the New Deal fell flat, except with the right-wing of the Grand Old Party (GOP), which never had trusted him. Sidelined during World War II, Hoover remained a pariah until President Harry S. Truman sent him abroad to gauge the possibilities of a postwar famine. Such work enabled Hoover to reengage in public service and to counter perceptions of him as a failed president. He later chaired a pair of presidential commissions on executive branch reorganization, one under Truman and another under Dwight D. Eisenhower. Opinionated and occasionally irascible, Hoover had differences with both presidents, but he grew to like Truman. As ex-president, Truman attended the opening of Hoover’s presidential library in West Branch, Iowa—a carefully scripted event in Hoover’s effort to refurbish his reputation. Truman often asked Daniel Rodriguez, a Waldorf waiter who attended to Hoover, about the former president’s health.16 Truman made these inquires during visits to New York in the 1950s, when he stayed in Apartment 32A at the Waldorf Towers. By then, Hoover lived one floor below—in Apartment 31A.17

Herbert Hoover celebrates his eighty-eighth birthday reading well wishes in 31A, his suite at the Waldorf-Astoria.

Hoover’s connection to the Waldorf began with Lucius Boomer, the hotel’s manager and an “old friend” who had invited Hoover to speak at the Waldorf’s opening in 1931.18 The two men shared an outlook that melded entrepreneurship with social responsibility. Boomer strove to improve the lives of his workers—and to discourage unionization— by providing social clubs, savings banks, employee bonuses, and health insurance.19 He identified scientific reasoning and impartial administration as the keys to prosperity and social progress. Hoover, too, extolled the virtues of a decentralized economy, gently guided by enlightened business executives and government officials. Yet his push for what one historian termed “cooperative, humane, common-sense capitalism” died during the Great Depression.20 Government intervention followed. FDR’s National Recovery Administration brought industrial codes, pressures to unionize, and strikes, which Boomer’s Waldorf resisted. Hoover, for his part, attacked the New Deal as a threat to virtues of hard work and individual initiative. In a memoir of his postpresidential years, he defined every national election between 1936 and 1952 as a “Crusade against Collectivism.”21 “The only person he ever criticized,” recalled James A. Farley, FDR’s postmaster general and Hoover’s neighbor at the Waldorf, “was Mr. Roosevelt.”22 Boomer, in contrast, received the highest praise. On the silver anniversary of the Waldorf’s launch, Hoover ranked him among “the greatest of American hotelman.” The Waldorf, he added, “has set comforts of living which I have personally enjoyed.”23

The Waldorf brought Hoover to America’s economic and cultural capital just a few hours’ drive of Washington. He and his wife, Lou Henry Hoover, had no plans to retire to their native Iowa. Hoover’s interest in West Branch lay in occasional visits to accept the approbation of Iowans, in preserving sites that marked his modest origins, in building a library like those constructed for Franklin D. Roosevelt and Truman, and in arranging his burial site.24 Curating his legacy was one thing. Finding a place to live—and to remain politically engaged—was quite another. Stanford University, from which Hoover and his wife had graduated, was an unlikely possibility. The family’s home in Palo Alto, an International-style mansion designed by Lou Hoover, ceased to be a refuge after Hoover’s sons, Herbert Jr. and Allan, had left to raise families of their own by the 1930s. Stanford lacked the cultural and political allure of the East Coast. Hoover disdained “the superficialities, the inanities, and the un-American atmosphere too frequent in New York.” Yet he knew that leaders “from the hinterland,” like himself, had found success there. New York provided a central location from which the former president could monitor the doings of his successor’s New Deal. It had “big money,” publishing conglomerates, and daily newspapers.

During his years in residence at the Waldorf-Astoria, former President Herbert Hoover met with many world leaders as well as former, future, and current presidents.

Above left: Hoover is seen to the left of Queen Elizabeth II as she addresses an official city luncheon, October 21, 1957. Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt can also be seen behind the queen.

Above right: Hoover meets with President John F. Kennedy in his suite, April 28, 1961.

“When one is interested also in the promulgation of ideas,” Hoover explained, “it is more effective to be at the distributing point than at the receiving end.” The city’s stores, museums, and galleries were world class. New York, Hoover wrote, “is a place of good food, of human comforts.”25 So, beginning in 1934, the Hoovers rented a suite at the Waldorf, where the president had enjoyed a “most pleasant” stay following his electoral defeat in 1932.26 By 1940, Apartment 31A had become their second home. Sadly, it was where Lou died in 1944. After her death, Hoover willed the California house to Stanford University and lived primarily at the Waldorf.27

Hoover led a comfortable life at the Waldorf. NBC newscaster Raymond Henle, a friend, thought Apartment 31A “lovely.” [?] Exquisite rugs covered the floors of the office and living room, and blue-and-white porcelain from the Ming dynasty reminded visitors of Hoover’s years in China. Also noteworthy was the former president’s desk, issued by the government and returned to the General Services Administration following his death. As a “permanent guest,” Hoover had access to the Waldorf’s amenities, including room service.28 Yet he was more than a guest. The Waldorf’s managers became confidants. Hoover appreciated Lucius Boomer’s many years of “loyalty and friendship.”29

Joseph Binns did some work for the second Hoover Commission, while keeping the former president supplied with cigars, flowers, sweets, and New York Yankees tickets.30 Hoover joined the hotel’s board of directors, to whom he conveyed the complaints of Waldorf employees.31 And he brought in business. In 1953, the Bohemian Club, an all-male society, honored Hoover, a forty-year member, at the Waldorf rather than in California, the site of its annual encampment. Organizers shipped redwood boughs east, to transform three of the hotel’s rooms into an ersatz forest. Cocktails, a black-tie dinner with tributes, and entertainment marked the festivities. Hoover “enjoyed every minute of it.”32 He then retired to his apartment, described by one associate as a “home-like suite.”33

Hoover’s daily routine reflected his multifaceted personality. He ate breakfast at 9:00 a.m., lunch at 1:00 p.m., and dinner at 7:30 p.m. His preferences were standard: eggs, bacon, and coffee in the morning; salad, stew, or goulash at midday; and consommé, potatoes, vegetables, and roast beef or fish in the evening. Meals ended with pastry, pie, or cherries jubilee. A martini preceded dinner. Hoover insisted on punctuality but forgave lapses and was generous with hotel staff. He supplemented Daniel Rodriguez’s income and presented gifts at Christmastime. When hotel employees stopped by to see his Christmas tree, he directed them to it with a wave of his hand. Hoover was close to his secretaries Bernice Miller and Elizabeth Dempsey, who either dined with him or arranged for others to do so (Hoover hated to eat alone). Dinner guests included political bigwigs or old friends, such as the broadcaster Lowell Thomas and his wife. A game of canasta closed the evening, and at 9:30 p.m. Hoover saw his visitors to the door. “He just treated you like part of his family,” Dempsey noted.34A Siamese cat provided additional companionship. “It’s a shame to have a cat and not have a dog,” Hoover joshed, “but what are you going to do with a dog on the 31st story in the Waldorf?”35

Such comments countered Hoover’s austere persona. “He gave sort of a coldness publicly, which really didn’t exist privately,” remembered Charles Edison, son of the renowned inventor and a resident at the Waldorf.36 Light observations oftentimes enlivened Hoover’s conversations. A trip to the ballpark, he averred, had “more curative powers” than medicine.37 Television enabled him to watch baseball as well as nightly newscasts, which he never missed.38 Other diversions included walks in the neighborhood around the Waldorf or trips to Key Largo, where he spent winters and fished. Fishing, Hoover quipped, “brings rejoicing that you do not have to decide a darned thing until next week.”39 Key Largo provided warmth and sunshine; Hoover once resolved to remain in Florida “until New York has reformed its weather.”40

Apartment 31A functioned as Hoover’s workplace. “I always imagine him sitting at his desk, and always occupied in writing,” Rodriguez recalled.41 Seven secretaries assisted him. Hoover replied to letters diligently, wrote his speeches, and published several books, including a biography of Woodrow Wilson, a mediation on fishing, and a collection of his correspondence with children. A magnum opus, Freedom Betrayed, was not published until a half century after his death. The delay was understandable: a friend said the work read like an “indictment” of FDR’s foreign policy.42 In letters to confidants and in his Memoirs (1952), Hoover labored to set the record straight about the Great Depression: it derived from events overseas, the tide began to turn “in June 1932,” and then, within a year, “America fell into the pit of the New Deal and never recovered . . . until it was absorbed in war.”43 The self-serving argument did little to lessen the appeal of Roosevelt or his programs.

Hoover, the historian Richard Norton Smith observed, “was not the sort to let old grudges die without a struggle.”44 He never became close to Dwight D. Eisenhower, whom he thought too liberal and less than enthusiastic about the recommendations of the second Hoover Commission. Hoover told one guest that Eisenhower “is decent and sincerely wants to do right but knows nothing of economics, government or politics.”45 He was annoyed when Vice President Richard Nixon, a protégé of sorts, did not ask him to campaign for the GOP ticket in 1960. Nevertheless, Hoover received Nixon, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson at the Waldorf.46 In 1962, for example, Nixon visited Hoover in Apartment 31A, where the former president advised the former vice president not to seek the California governorship. “California basically is a great state,” Hoover explained, “but it’s quite parochial. You belong on the national and international scene. You can’t do that in California.”47 Nixon lost the race for governor and thereafter relocated to New York, where he prepared his political comeback.

The attention of presidents reminded Americans of Hoover’s long public service and added to his image as “the Sage of 31-A.”48 In 1958, Eisenhower sent Hoover to represent the United States at the opening of the World’s Fair in Brussels, where Belgians lauded his relief efforts during the Great War. At home, Hoover supported charities such as the Boys Clubs of America, of which he served as national chairman. He sat for interviews, commented on current events, and dispensed advice: “Work. Don’t sit around worrying about ills and pills.” 49 Addressing the Republican National Convention in 1960, the former president avoided partisan bombast and championed widely shared values of freedom, opportunity, and patriotism.50

The Waldorf played a modest role in Hoover’s bid to regain his political relevance and reputation. The hotel attracted countless international dignitaries. Hoover visited with two presidents of Mexico, Adolfo López Mateos and Miguel Alemán Valdés, the latter of whom had a flat at the Waldorf.51 Neighbors at the Waldorf Towers became friends and admirers. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor, for example, mourned Hoover’s death, in 1964, as a “great loss to the world.”52 Earlier, Jim Farley, who had fallen out with Roosevelt, served on the second Hoover Commission and launched a fund-raising drive in Hoover’s name for the Boys Clubs of America.53 “It was ever a pleasure to visit him in his apartment and discuss the happenings of the day,” Farley stated. “He was one of the most dedicated, patriotic and unselfish Americans I have ever known.”54 Charles Edison spent time with Hoover, shared his political outlook, and praised him in an oral history, as did Farley. “He had the tremendous loyalty of his friends,” Edison explained. “They just worshipped him.”55 The words of well-wishers cheered Hoover. He “got a big kick” when a doorman shouted: “I cut your son’s hair when he was a little boy.”56 Jean MacArthur asked after Hoover, for she and her husband, General Douglas A. MacArthur, lived at the Waldorf Towers.57 Nevertheless, Hoover failed to cajole MacArthur into endorsing Eisenhower during the 1952 election. The former president’s messages and telephone calls went unanswered as MacArthur remained aloof from Ike, his former subordinate. Such prodding, according to Binns, showed Hoover “trying to do what he thought was best for the party and for the country.”58 Yet it also underscored that physical proximity did not lead to political pull. The sporadic attention Hoover received from presidents and other leaders boosted his “political star,” says his biographer, Joan Hoff Wilson, without making him “a truly influential political figure once again.”59

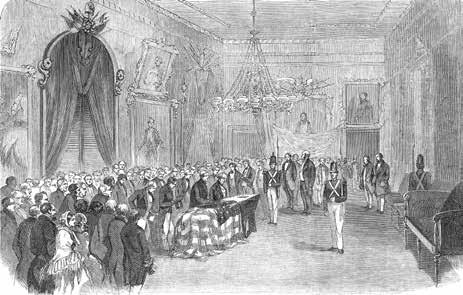

By the time of his death, Hoover had won a qualified rehabilitation: respect for his nonpresidential achievements and acknowledgment of his troubled presidency. As his health declined, Hoover relied on family and friends. To a neighbor at the Waldorf, he said: “Well, if it isn’t too much trouble, come and see an old man soon again, will you?”60 Hoover passed away in Apartment 31A on October 20, 1964. Although Hoover’s State Funeral did not include observances at the Waldorf, black-draped photographs of him were placed in the lobbies of the hotel and towers.61 Americans mourned the better aspects of Hoover’s life. Retrospectives extolled his perseverance, integrity, compassion, and public service.62 Editorial writers discussed his presidency guardedly. The Washington Post found Hoover “the victim of circumstances over which he had no control,” the fallout from which made him, as the Buffalo Evening News put it, “the most baselessly maligned of men.”63

Subsequent scholarship on Hoover, a political scientist explained, has “dispelled the myth of an intransigent, laissez-faire ideologue,” and his reputation as a humanitarian and public servant rebounded.64 But, according to the journalist John Bartlow Martin, he lacked the ability to “feel in his bones the needs of the American people.”65 Hoover’s failure to find a solution to the Great Depression remained his albatross. A newspaper in Northern Ireland announced his death with the headline: “Slump Years President Dies.”66 An energetic ex-presidency, headquartered in Apartment 31A, proved no match for a widely held view, aptly summarized by the Wall Street Journal in 1974: “Hoover’s presidency, as a whole, was an unfortunate detour in an otherwise brilliant career.”67

Hoover’s association with the Great Depression partially explains his heartfelt devotion to the Waldorf. The economic collapse that wrecked his presidency challenged the values of self-reliance and private initiative that he had long embodied. But Boomer’s hotel offered a beacon of hope. The Waldorf’s opening, according to Hoover, was a “monument to pluck,” to American entrepreneurship, and to faith “not only in the future of the hotel but in that of America itself.” The result, he asserted, was an institution that provided “a forum where more or less everybody in America meets in order to pass the time of day.” The Waldorf also became “a marketplace, a ‘Rialto,’ a center of music and dancing, a club, a place for feasting, an office for business, a panorama of fashionable life, and, best of all (best for me at least) a household in which everybody manages to be supernaturally obliging and kind.”

The former president jotted these words in 1939, in