11 minute read

Made in New York

Below:

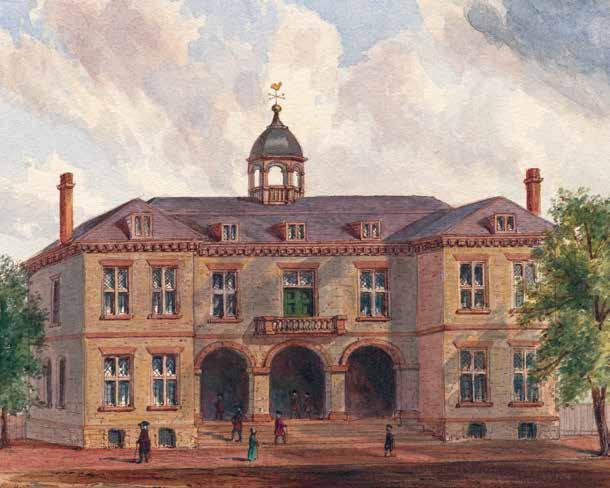

Pictured here in an 1859 issue of the Illustrated London News, this building at 488–92 Broadway was built in 1857 to house E. V. Haughwout & Company, a luxury goods store. It was here that First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln ordered a State Dinner Service for the White House in 1861.

B. Altman and Company’s flagship department store at 355–71 Fifth Avenue is seen here c. 1914. Altman provided decorating services and furnishings for the newly renovated White House during the Truman presidency.

Kennedy Acquisitions

In 1961, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy almost immediately dove into a notable project to bring a greater sense of history to the interiors of the White House. With an advisory committee and a professional museum curator, she refurbished rooms and added antiques received by donation or acquired with donated funds. These acquisitions included a silver plateau made by New York City silversmith John W. Forbes, circa 1820–25. With plinths decorated with eagles, this mirror-floored table centerpiece was installed on the table in the old Family Dining Room as a rare American counterpart to the gilded bronze French plateau purchased in 1817 for President James Monroe that was exhibited next door in the State Dining Room.

Furniture included pieces by two of the foremost New York cabinetmakers of the early nineteenth century—Duncan Phyfe and Charles-Honoré Lannuier. The popularity of the high-style product of the large Phyfe workshop has led many pieces once firmly attributed to Phyfe to be redesignated “in the manner or style of Phyfe.” Under Mrs. Kennedy, however, the White House received pieces with strong Phyfe provenances—for the Library on the Ground Floor a ten-piece suite of seat furniture, including settees and chairs in the Regency style, made circa 1810, and for the Ground Floor Corridor an early Grecian style pier table, made circa 1834. Other pieces with Phyfe attributions can be found in the Green Room, which was refurbished in 1972 with furniture by Phyfe or of the Phyfe style.

One of the earliest Kennedy acquisitions was a circular table (guéridon) made by Lannuier, circa 1810. Bearing a paper label in English and French for “Honoré Lanniuer [sic] Cabinet Maker (from Paris),” [?] it was lauded by Peter Kenny of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in his seminal book: “The great masterpiece of Lannuier’s amalgamated style is [this] superbly balanced and proportioned gueridon.” [?] It has been in the Red Room since 1961, joined there by two additional Lannuierlabeled tables acquired in 1974 and 1993.

Textiles for many of the public rooms in the Kennedy administration were secured from Scalamandré Silks (founded in 1929 by Franco Scalamandré and his wife Flora Barranzelli, to focus on re-creating fabrics used in historic houses and museums; for more than forty years its mill occupied an early twentieth-century industrial building at 37–24 Twenty-Fourth Street, Long Island City, now the remodeled “Silks Building”). Silks made by or acquired through the firm were used in the Green Room, Blue Room, and Red

Room, and it would provide later generations of fabrics for those and other White House rooms. One Kennedy administration acquisition not made in New York, but depicting New York, is the scenic wallpaper entitled “Views of North America.” Made by Jean Zuber et Cie, Rixheim, France, circa 1834–36, this paper, removed from a house in Thurmont, Maryland, in 1961, was installed as a truly panoramic paper in the oval Diplomatic Reception Room in 1962 as an additional donation from the National Society of Interior Designers. Along with scenes of Boston, West Point, Niagara Falls, and the Natural Bridge of Virginia, the paper depicts, as seen across from Weehawken, New Jersey, what was called a “General View of New York.”

Several fine pieces made by the French-born New York cabinetmaker Charles–Honoré Lannuier were acquired for the White House during the Kennedy administration including this marble-topped center table marked with Lannuier’s paper label.

In 1819, while at the White House to paint a portrait of President James Monroe, the artist Samuel F. B. Morse commented that the rooms were furnished and decorated “in the most splendid manner; some think too much so, but I do not. Something of splendor is certainly proper about the Chief Magistrate for the credit of the nation.” For over 175 years, the manufacturers, designers, and merchants of New York City have been instrumental in keeping the furnishings and décor of the White House up to Morse’s standard for the presidents, first families, and the nation.

Notes

Principal sources are two White House Historical Association publications: Monkman, Betty C. and William G. Allman, Lydia S. Tederick, and Melissa C. Naulin, Furnishing the White House: The Decorative Arts Collection (Washington, DC: The White House Historical Association, 2023) and Allman, William G., Official White House China from the 18th to the 21st Centuries (Washington, DC: White House Historical Association, 2016, 3rd ed.). Quotations within these sources are separately cited.

1. Voorsanger, Catherine Hoover and John K. Howat, eds., Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825–1861 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000), 42, 287.

2. Official China, 12–13; Furnishing, 4–5, 340.

3. Furnishing, 84–85, 350; Diary of Elizabeth Dixon, December 1, 1845–February 10, 1847, Connecticut Historical Society Collection, quoted in Furnishing, 85, full text of diary entry in Official China, 65. Herts Brothers: Furnishing, 164, 359.

4. Haughwout & Dailey – Pierce State Service - Official China 72-75, Furnishing, 100-01, 352. Horace Greely, Art and Industry as Represented in the Exhibition at the Crystal Palace, New York, 1853–1854, Showing the Progress and State of the Various Useful and Esthetic Pursuits (New York: Redfield, 1853) quoted in Official China, 74. Professor Benjamin Silliman, Jr. and C.R. Goodrich, Esq., eds., The World of Science, Art and Industry Illustrated from Examples in the New York Exhibition 1853-1854 (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1854), 129, quoted in Official China, 74. E.V. Haughwout & Co. - Lincoln State Service - Official China, 78-86, Furnishing, 110-14, 354.

5. Haviland & Co. – Grant State Service - Official China 90–96, Furnishing, 110–11, 114, 120–21, 354–55. Hayes State Service - Official China, 100–21, unnumbered insert following; Furnishing, 153–55, 357–58.

[notes to be formatted and numbered--not sure where numbers go] p.58 – Pottier & Stymus, Furnishing, 136, 138-41, 356. p.59 – Herter Bros. - Furnishing, 141, 144-45, 355-56. p.60 – Tiffany & Co. – Hayes candelabra - Furnishing, 152-53, 357; McKinley presentation cup - Furnishing, 186-87, 362; Johnson State Service - Official China, 90-96, Furnishing, 276-77, 377; Arthur redecoration - Furnishing, 168, 169-173, 360-61; Tiffany Studios rugs – 224-25, 367. p.62 – McKim, Mead & White - Furnishing, 202-05, 364. p.63 – Caldwell & Co. - Furnishing, 206-07, 364. p.64 – Steinway & Co. – 1903 - Furnishing, 212-13, 362; 1938Furnishing, 236-39, 369. B. Altman & Co. - Furnishing, 237, 240-41, 369; Official China, 176-183. p.65 – Edward Fields - Furnishing, 247, 298. p.68 – Kennedy Acquisitions – Forbes plateau - Furnishing, 56, 263, 346; Phyfe – 258-59, 269, 373, 376; Lannuier - Furnishing, 259261, 374; Peter Kenny et al., Honoré Lannuier, Cabinetmaker from Paris (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998), in 1881, when chester a. arthur came to the presidency, he brought his New York City sophistication with him. He had practiced law in New York and served as collector of the port of New York before being nominated, and then elected, as James A. Garfield’s vice president in 1880. On the night of September 19, 1881, Arthur was at home in New York, a fine brownstone residence on Lexington Avenue. There he received word—not unexpected—of the death of President Garfield, who had never recovered from an assassin’s gunshot wounds two months earlier. At 2:15 a.m. on September 20, Arthur took the Oath of Office in his parlor, becoming the second president—after George Washington—to be sworn in to the presidency in New York City.

76-77.

Arthur moved to Washington, but he did not move into the White House. He toured it, found it shabby and unfit for a president and declared he would “not live in a house like this.” Instead, after some refurbishment, he would undertake a complete redecoration of the State Rooms (except the Green Room). As the historian William Seale has observed, Arthur, a sophisticated New Yorker, was attentive to the “aesthetic interior decoration [then] current in the centers of style.” Thus Louis Comfort Tiffany and his Associated Artists of New York City, specialists in Aesthetic decorative effects, were a natural choice for Arthur’s White House redesign.

President Arthur enlisted Tiffany’s services in 1882, at a time when the artist was in the early years of his career. The son of jewelry magnate and Arthur’s close friend, Charles Lewis Tiffany, Louis Comfort was on the rise as a young artist and designer in his own right, and Arthur may have been impressed by the important commissions Tiffany had already accomplished, including a redesign of the Seventh Avenue Armory and the Fifth Avenue home of millionaire George Kemp. For these commissions and for the White House redesign, Tiffany worked in collaboration with artists such as Candace Wheeler, Samuel Colman, and Lockwood de Forest. These were the Associated Artists, with showrooms at 333-335 Fourth Avenue , they were in operation by 1881.

In preparation for the White House redesign, Arthur conducted a thorough inventory of White House furnishings, condemning to auction those he deemed inferior, among them Nellie Grant’s birdcage and some clothing owned by President left President Chester Alan Arthur is remembered in New York City, his home before and after his presidency, with a sculpture in Madison Square Park. The monumental bronze portrait by George Edwin Bissell was dedicated on June 13, 1899. previous spread Artisans at work on Tiffany glass, 1913, and a view of the North Entrance to the White House as embellished with Tiffany glass during the presidency of Chester Arthur, 1893.

Louis Comfort Tiffany, seen here in 1871, was just setting out on his career in 1882 when President Arthur commissioned his services to redecorate the White House.

Lincoln. Under Arthur’s orders, Tiffany and his collaborators transformed the Red Room, the State Dining Room, and the Entrance Hall, with additional work on the Blue Room and the East Room. No furniture was commissioned, although new furniture had generally been commissioned or selected for White House redecorations. Instead, the Tiffany redesign was accomplished entirely through new textiles, light fixtures, decorative painting, and, most notably, stained glass.

Perhaps the most legendary of these new decorations was the colored glass screen that Tiffany crafted to separate the Entrance Hall from the Cross Hall. The screen, made of opalescent leaded glass, was a mosaic of what one contributor for Harper’s Weekly described as “varying but symmetrical patterns, composed of sheets of opalescent glass incrusted with vitreous jewels of topaz and ruby and amethyst.” It is unknown exactly where the glass was made and the screen produced, but Tiffany was, at the time of the White House renovation, conducting his glassmaking experiments at the Heidt glasshouse in Brooklyn, New York. The opalescent sheet glass industry was in its early years in the 1880s and Tiffany would not establish his own glass furnace until 1892 in Corona, Queens. Prior to that time, Tiffany purchased flat glass from the Heidt and Thill glasshouses in Brooklyn as well as Opalescent Glass Works in Kokomo, Indiana.

As Martin Filler has shown, President Arthur’s redecoration and his selection of Tiffany’s New York firm were more than a demonstration of luxury and prestige; they were also deeply political. Because he succeeded the assassinated James Garfield, Arthur was acutely aware that he was assuming leadership of an anxious and grieving nation. In appealing to the vitality and vibrancy of Tiffany’s cosmopolitan and highly Aesthetic designs, Arthur hoped to inspire the same in his countrymen. Tiffany’s glass screen is an example. Highly functional, the screen insulated the adjacent drawing rooms from cold weather while dazzling White House guests with its rich colors and carefully considered design. Four American eagles, the United States shield, and the initials “U.S.A.” worked into the design were intended to instill feelings of pride and patriotism in all who entered the residence. Indeed, there is some evidence that it worked. Reporting on the White House redecoration in December 1882, the Washington Post announced, “No longer is the White House simply the home of a Republican

President. Lo, it is the temple of high art!”

In spite of the favorable press that Arthur’s redecoration received at the time, tastes changed at the White House almost as frequently as administrations. The dawn of the Progressive Era brought new decorative trends and politics to the Executive Mansion. In 1901 Theodore Roosevelt assumed the presidency—again after an assassination— and went on to champion social, political, and economic reform. The president and First Lady Edith Roosevelt wasted little time in renovating their new home. Also New Yorkers, they again they looked to New York, hiring the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White to, as the New York Times reported, “wipe out all modern features and restore the mansion to its original Colonial simplicity.” In the new century Arthur’s big city opulence seemed garish, out of date and out of touch with the average American experience. Tiffany’s glass screen was removed and the State Rooms the Associated Artists had redecorated were once again completely redone.

A stained glass worker is featured in one of a group of illustrations entitled Establishment of Louis C. Tiffany & Co.—Associated Artists, published in Harper’s Bazar, 1881.

right above left can you make all black and whites on this spread the same tone

Both functional and beautiful, Louis Comfort Tiffany’s jewel toned glass screen transformed the White House Entrance Hall. The symmetrically patterned, opalescent glass was colored with topaz, ruby, amethyst. This black and white photo has been colorized to approximate the appearance of the legendary screen.

Women at work in the Embroidery Room at Louis C. Tiffany & Co., 1881.

The Red Room as decorated by Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Associated Artists for President Arthur featured painted walls in Pompeian red. The ceiling was finished in gold and copper tones.

In the East Room, Tiffany redid the ceiling in silver leaving much of the earlier decor in place.

The State Dining Room in the 1890s retains the Tiffany wallpaper, ceiling, curtains, valances, and light fixtures.

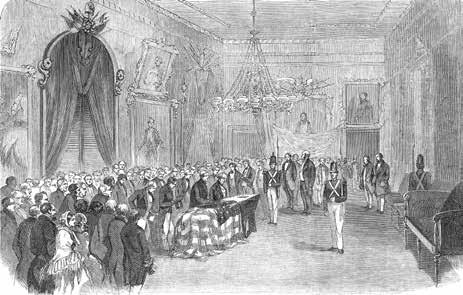

Harper’s Weekly illustrations published in the January 1883 issue captures visitors admiring the new Tiffany decor in President Arthur’s White House.

Roosevelt’s successors continued an interest in restoring styles evoking the American past. In 1925, First Lady Grace Coolidge shopped the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for inspiration on White House art and furnishings, paying special attention to “examples of furniture of the early Puritan days.” President Harry Truman’s televised tour of the White House in 1952 generated interest in locating and reclaiming White House antiques. And in 1961, when First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy began her wide-ranging project to bring original furnishings and associated period decor back to the White House, she told Life magazine, “Thank goodness for Roosevelt. He undid all the bad that was done by Arthur.”

When Tiffany’s glass screen was removed from the White House in 1902, it was sent to auction and purchased by the owner of a Maryland hotel. In 1923 the hotel was destroyed by fire, and it is assumed that the screen was likewise lost. Yet it continues to interest scholars of White House interiors and captivate the public. It stands an enduring legacy of the Arthur administration, recalling a time when the Aesthetic style so suited a president from New York that he brought artists from that city to remake the White House State Rooms to his taste.

Notes

1. Quoted in William Seale, The President’s House: A History, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2008), 1:513.

2. Seale, President’s House, 1st ed. (1986), 1: 538.

3. Roberta A. Mayer and Carolyn K. Lane, “Disassociating the ‘Associated Artists’: The Early Business Ventures of Louis C. Tiffany, Candace T. Wheeler, and Lockwood de Forest,” Studies in the Decorative Arts 8, no. 2 (2001): 7, 12.

4. Ibid., 2–36.

5. Francis de Sales Ryan, “President Arthur Swept out White House in 1882 Auction: Arthur Cleared White House,” Washington Post , August 17, 1952, M1.

6. Seale, President’s House , 2nd ed., 1:517–23.

7. “The New Decorations at the White House,” Harper’s Weekly, January 6, 1883, copy in Arthur/Tiffany Files, Office of the Curator, The White House; “Esthetic Decoration,” Washington Post, December 20, 1882.

8. Martin Filler, “Red, White, and Tiffany Blue,” Magazine Antiques, March 2009.

9. “Esthetic Decoration.”

10. “White House Renovation: Mrs. Roosevelt Proposes to Restore the Mansion to Its Original Colonial Simplicity,” New York Times, April 24, 1902, 3.

11. “Mrs. Coolidge Shops for Ideas on Art: Visits American Wing at the Metropolitan for White House Suggestions,” New York Times, November 20, 1925.

12. “White House Hunt Locates Antiques: Truman’s Efforts to Restore Relics Result in Lively Leads, But Too Late,” New York Times, January 20, 1953.

13. Hugh Sidey, “The First Lady Brings History and Beauty to the White House,” Life, September 1, 1961, reprinted in White House History, no. 13 (Summer 2003): 6–17, quotation on pages 11, 13.

14. Filler, “Red, White, and Tiffany Blue.”