16 minute read

STREET SCENES: A New York Pedestrian’s Chance Encounters with Presidential History

MATT GREEN

Matt’s ongoing walk of New York City will ultimately cover every street in the five boroughs: the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, and Staten Island. The boroughs are clearly illustrated in this map made in 1900, when Staten Island was still known as Richmond. Matt has been on his journey for more than eleven years and has covered over 9,400 miles.

Matt’s years of walking every street in the five boroughs of New York began December 31, 2011. Blindfolded by friends, he was driven to Amboy Road in Staten Island, a randomly selected location, where he removed the blindfold and started walking.

Disembarking the big orange ferry after a ride across New York Harbor from Staten Island, a few friends and I start to make our way uptown from the southern tip of Manhattan. Unlike the modernist numbered thoroughfares that methodically divide most of Manhattan into tidy rectangular blocks, the narrow streets down in this part of the island evoke an older era. They bend and meander, tracing the routes of the first roads laid out here by Dutch colonists almost four hundred years ago. Nearby Wall Street gets its name from the wooden wall that once stood along its path, a protective barrier built at what was then the northern edge of the settlement known as New Amsterdam. And Wall Street, in turn, has given this neighborhood its name: the Financial District. But even as the area has been thoroughly shaped by the relentless, unsentimental tide of capitalism, there remains a romantic sense of history hanging in the air.

The friends joining me on this walk are marking the first day of my multiyear quest to walk every block of every street in the five boroughs of New York City. Adding in parks, cemeteries, beaches, and various other public spaces, it will end up being a journey of more than 9,000 miles on foot, all within the bounds of a single city. I don’t know it at the time, but it will take me well over a decade to complete.

We had started the day at a randomly selected location, the 4300 block of Amboy Road in Staten Island. I didn’t even know where I was until the friends who had driven me there took off my blindfold. The plan was to get my bearings and map out a long walk to the ocean, celebrating New Year’s with a plunge in the chilly Atlantic. We decided to head north to the ferry and then across the bottom of Manhattan to the Brooklyn Bridge and on through Brooklyn to Brighton Beach. The 27 miles of blocks we’ll cover constitute just one puny little line on my progress map, the first tiny bite taken out of a truly immense apple.

A few blocks from the ferry terminal, at Broad and Pearl Streets, we pass Fraunces Tavern, a stout three-story brick building. The name is familiar to me—some kind of association with George Washington—but I’m not sure of the details.

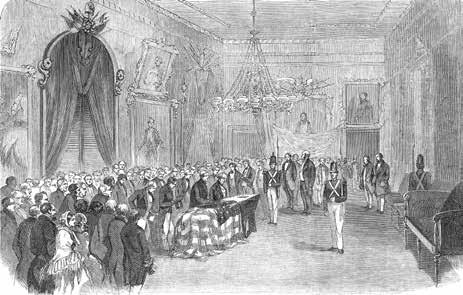

Rather than read about the areas I’m going to walk ahead of time, I like to just walk, try my best to pay attention, and take lots of photographs. Then I research what I see afterward. I don’t know enough to decide what’s important beforehand; I just let things catch my eye and then I dig in from there. What I end up with is not a thorough, organized account of the city’s history but instead an idiosyncratic understanding that builds slowly and circuitously, often in unpredictable and oblique ways, as individual threads of discovery that seem insignificant on their own begin to weave a dense, tangled web of connections across many years and miles. Which is a wordy way of explaining why it’s only later, after the day’s trek is done, that I read that Fraunces Tavern is where, not long after the final British troops left New York City in 1783 at the end of the Revolutionary War, General Washington bade a poignant farewell to an assemblage of officers of the Continental Army. One of those officers, Colonel Benjamin Tallmadge, penned his recollections some years later:

After the officers had taken a glass of wine General Washington said “I cannot come to each of you but shall feel obliged if each of you will come and take me by the hand.” General Knox being nearest to him turned to the Commander-in-chief who, suffused in tears, was incapable of utterance but grasped his hand when they embraced each other in silence. In the same affectionate manner every officer in the room marched up and parted with his general in chief. Such a scene of sorrow and weeping I had never before witnessed and fondly hope I may never be called to witness again.1

DAY 30: January 29, 2012

experience. The ranch-style houses, the front yards, the trees planted along the sidewalks—all pleasant features of a lovely neighborhood but not the kinds of things that jump out and grab your attention as you pass by. But sometimes the wonder of a place’s present can be appreciated only in relation to its past.

A pedestrian could be forgiven for walking the three blocks of Charlotte Street in the South Bronx and coming away without a distinct memory of the

A pedestrian visiting Charlotte Street in 1977, for example, would likely have found the scene much more memorable, as Jimmy Carter discovered on an October morning of that year. A day after addressing the United Nations General Assembly on the subject of nuclear disarmament,2 President Carter headed uptown to witness firsthand the devastating urban decay that had ravaged the South Bronx. Iconic photos from his stop at Charlotte Street show him striding across vacant lots filled with rubble in what could be mistaken for a bombed-out war zone.3 The Bronx borough historian, Lloyd Ultan, told the New York Times that he can’t even identify exactly where on Charlotte Street the photos were taken; there’s nothing that can serve as a landmark amid the utter desolation and emptiness.4

Matt’s walk in the South Bronx on Day 30 led him to Charlotte Street, an area also walked by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. What Carter found here was bleak—a dismal scene of urban decay. The area has since been so transformed that even the Bronx borough historian is not able to pinpoint the exact spot where this photograph of Carter’s visit was taken.

Today’s tranquil, ordinary Charlotte Street is a far cry from those dark days. It serves as a reminder of how quickly things can change when enough people with enough power decide a change needs to be made. But it also points to the lingering weight of stereotypes. Photos of the Bronx from the 1970s shape the public perception of the borough more than the modern-day reality does. And the reality, as you soon discover once you set foot there and say hi to a few folks, is that the Bronx, like everywhere else, is full of people who are exactly the same as you, people trying to make a living, find love, care for their family, and do something meaningful with their time on earth.

I’m also struck by something else when I look at those photos of Jimmy Carter. I see a Georgia peanut farmer, fresh off grappling with the perils of international nuclear proliferation, now facing an overwhelming scene of urban despair here at home. The array of challenges facing anyone who dares to shoulder the weight of the presidency is so vast. It must be absolutely terrifying to take the Oath of Office and realize everything is now within your purview, all the struggles and anguish of an enormous nation in a tumultuous, ever-changing world. The ambition of anyone who could attempt such a thing is beyond me.

Strolling through Manhattan’s East Village, passing a dense collection of row houses and apartment buildings on Second Street, I come upon a verdant enclave, a tiny cemetery occupying perhaps a quarter of a block. According to a sign on the fence, this is the New York City Marble Cemetery. It opened in 1831 and it’s the final resting place of a prominent merchant named Preserved Fish. I imagine him introducing himself at a party: “The name is Preserved Fish, but you can just call me Pickled Herring.”

As I later discover, the cemetery was also the notso-final resting place of an even more prominent figure: President James Monroe. After the death of his wife Elizabeth in 1830, he moved from his native Virginia to New York City to live with his daughter and her husband. He passed away the following year and was buried in the family vault of his son-in-law here at the cemetery.5 After twenty-seven years of peaceful repose, his remains were disinterred in 1858 and shipped to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, in grand style, a move initiated by Virginia’s governor, Henry A. Wise, as an expression of state pride.6 At Hollywood, President Monroe is entombed in a granite sarcophagus surrounded by an ornate cast-iron Gothic structure known to locals as “The Birdcage.”7

Another twenty-seven years after President Monroe’s departure, a new president would be laid to rest in New York City, this one for keeps. If you’re wondering who I’m talking about, you’ll just have to puzzle out the answer to the age-old riddle: Who is buried in Grant’s tomb?

New York City Marble Cemetery was for a time—from 1831 until 1858—the resting place of President James Monroe. Matt’s walk through the East Village on Day 98 took him past this tiny cemetery. Monroe is now buried in Richmond, Virginia, and is not mentioned on the plaque that hangs on the front gates. However, the wealthy merchant Preserved Fish (seen above c. 1830) made it into the posted history.

Unlike President Monroe, whose interment in New York was ultimately temporary, President Grant remains buried in Manhattan, in what is the largest mausoleum in North America. Matt’s walk took him to Grant’s Tomb on Day 1,941 (April 23, 2017).

DAY 207: July 24, 2012

Heading down Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan, I pass under the Brooklyn Bridge, beneath a set of steel arches that support the roadway above. Chainlink construction fencing abounds, preventing curious passersby from getting a good look at the monumental stone anchorage of the bridge on either side of the street.

drawn to the south side of the street, to the rows of headstones in St. Peter’s Cemetery, the oldest Catholic cemetery on the island. But then I notice something unusual sticking out on the house-lined north side of the street: a large statue of a horse standing in a neatly planted bed of roses and shrubs.

After examining the sporty metallic equine, its muscles and veins visibly rippling beneath its skin, I turn my attention to the adjacent house. It’s much grander and older-looking than its neighbors, Greek revival in style with a quartet of two-story Corinthian columns supporting the roof of a stately portico.

Researching the house later on, I learn that one former resident was Julia Gardiner Tyler, the second wife and widow of John Tyler, who moved here to live with her mother after the former president passed away in 1862. While her husband may have had a fairly undistinguished run as president, he did establish a handful of firsts appreciated by trivia buffs. Following the death of William Henry Harrison, he became the first vice president to ascend to the highest office in the land without being elected, earning him the derisive nickname “His Accidency.” He was also the first president to lose a spouse while in office, and became the first to get married in office when he and Julia tied the knot in 1844.

Matt’s Day 207 walk led him once again under the Brooklyn Bridge. This photo he took in 2022 shows how construction fencing blocks the view of the bridge’s monumental stone supports.

Despite hailing from New York State, Julia came to adopt the southern sympathies of her plantation-owning husband, whose casket was laid to rest in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, just a few years after James Monroe’s, draped not in the Stars and Stripes but in a Confederate flag.8 While living on Staten Island, Julia continued to advocate for southern causes during the Civil War. Two of her sons fought in the war on the Confederate side.9

And speaking of her offspring, here’s the most amazing bit of Tyler-related trivia that I find along the winding path of discovery that began with that odd horse statue: Julia and John have a living grandson. I repeat: John Tyler, who was born in 1790, has a living grandson, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, who is 94 years old.10 Harrison’s father, like his father before him, married a much younger woman after the death of his first wife, stretching out the generational timeline and making this astounding feat possible.11

DAY 1,045: November 9, 2014

This ethnic career path was established the way so many others have been throughout time: A pioneer learns a specific trade and then teaches it to newer immigrants looking to establish a foothold in an unfamiliar country, in this case Afghans fleeing their homeland after the Soviet invasion began in 1979. The knowledge gets handed down over the generations, and, before you know it, and in a beautiful mishmash of cultures, you end up with an American city chock-full of Afghan-run chicken shops all named for a U.S. president who just so happened to share the first syllable of his last name with a certain American state featured prominently in the world’s most popular fried chicken brand.12

Barack Obama has a significant personal connection to New York City. He completed his undergraduate degree at Columbia University and spent a couple of years afterward living and working here. After all my walking, however, I’m starting to pick up on a different sort of relationship between the city and President Obama, one based not on residency but rather on the powerful symbolic quality of his presidency and the sense of possibility his election provided to many underrepresented communities. This relationship reveals itself little by little in the physical fabric of the city, expressed every now and again in a modest tribute like the name of a local business or a mural on the wall of a school.

But today, in Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills, I witness an unprecedented level of devotion to our forty-fourth president. I come across three different Obama-inspired bodega names within a seven-block stretch of Fulton Avenue: Obama Tobacco, Obama 44 Deli & Grocery, and King Barack Candy Store.

This brings to mind another memorable business name I encountered back in 2012 in Brownsville, Brooklyn: Obama Fried Chicken, a new addition to the proud New York tradition of presidential chicken. You can find a few Lincoln Fried Chicken shops around town, but the dominant player in this game is John F. Kennedy. There are dozens of Kennedy Fried Chicken joints cooking up birds all across the city. While they often have similar appearances and menus, the restaurants are generally run independently of each other and are largely owned and operated by Afghan immigrants.

Barack Obama, seen (above) walking to his car after arriving on Marine One at the Downtown Manhattan Heliport in 2010, attended college and worked in New York in the 1980s. The city’s affection for the president was evident in a seven-block stretch of Fulton Avenue Matt walked on Day 1,045, where three bodegas were named for him: Obama Tobacco (right), Obama 44 Deli & Grocery (above right), and King Barack Candy Store (opposite).

DAY 1,364: September 24, 2015

The construction fencing beneath the Brooklyn Bridge at Pearl Street is still there, years after I first walked by, continuing to block public access to the bridge’s massive stone anchorage.

DAY 1,521: February 28, 2016

Making my way across Curry Hill in Manhattan, I stop at Kalustyan’s, the renowned spice and specialty food emporium that has been in business here at 123 Lexington Avenue since 1944. As much of an institution as the store has become, however, Kalustyan’s is not the most notable resident the building has ever had. That honor belongs to Chester Alan Arthur, who made a name for himself as a New York attorney before entering politics.

One significant case Arthur took on in his younger years was an 1854 lawsuit against the Third Avenue Railway Company filed on behalf of Elizabeth Jennings, who had been thrown off a streetcar on her way to church because she was Black. The successful suit paved the way for the eventual integration of all of the city’s public transportation in 1873.13 Elizabeth Jennings, whose place in history has long been overlooked, is now slated to be honored in the coming years with a statue in Manhattan commemorating her bravery and determination, part of a push to diversify the city’s collection of public statues, almost all of which depict males.14

Two notable sculptures of U.S. presidents have been taken down in New York in recent years amid this reconsideration of what our public art should be depicting and honoring. A statue of Thomas Jefferson was removed from the City Council chamber in 2021 because of his history as an enslaver of more than six hundred people during his life. And a statue of Theodore Roosevelt riding a horse and flanked by a Native American man and a Black man on foot was removed from the entrance of the American Museum of Natural History in 2022 because of its depiction of the men as subservient to President Roosevelt.

But let’s get back to 123 Lexington, which was the site of a very significant moment in presidential history, a moment whose memory is only tenuously carried into the modern day by an inconspicuous plaque mounted behind glass by the foyer door leading to the apartments above Kalustyan’s. The plaque reads, in part:

HERE ON SEPTEMBER 20, 1881, AT 2:15

A.M., CHESTER ALAN ARTHUR TOOK HIS OATH OF OFFICE AS 21st PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES UPON THE DEATH OF PRESIDENT JAMES A. GARFIELD, KILLED BY

A DISGRUNTLED OFFICE SEEKER.

On Day 1,521, Matt’s walk took him through President Chester A. Arthur’s old neighborhood, Curry Hill in Manhattan. It was at his home at 123 Lexington Avenue that Arthur took the presidential oath of office following the assassination of President James A. Garfield in 1881.

President Arthur might not recognize his old home on Lexington Avenue if he were to see it today. In his time (right), the entrance was on the second floor at the top of a short flight of stairs. Today, the building has been transformed to accommodate a storefront for Kalustyan’s (above), where spices have been sold since 1944.

David can you improve color?

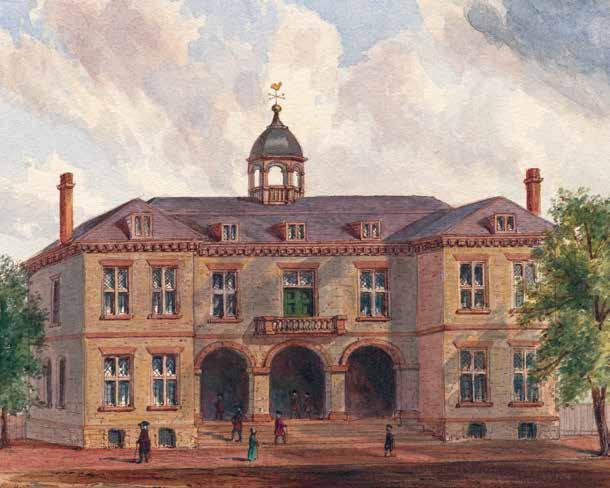

This event made President Arthur the second, and to date last, president to take his Oath of Office in New York City. An imposing statue of George Washington standing outside the present-day Federal Hall on Wall Street very visibly calls attention to the location where our first president was sworn in, but the building where Chester Arthur assumed the duties of the presidency, a building that is still standing, unlike the Federal Hall of President Washington’s era, is all but invisible to the throngs of pedestrians passing by on the sidewalk every day.

DAY 3,545: SEPTEMBER 13, 2021

More than nine years after I first walked under the Brooklyn Bridge on Pearl Street, the construction fencing is still standing and preventing the public from approaching the bridge’s stone anchorage. While there’s nothing in particular about the anchorage that would call out to someone walking by, I’ve learned over the years that surprising details and stories are hidden all over the city, and it’s not unusual for a seemingly pointless inspection of your surroundings to end up leading you somewhere you never expected.

DAY 3,800: May 26, 2022

I’ve been working on an article about my NYC walk and some of the presidential stories I’ve stumbled across along the way. While many presidents are woven into the fabric of the city in ways large and small, I’ve felt the presence of George Washington more than any other over the years. This makes sense, given that he led the Continental Army here during the early stages of the Revolutionary War and then served as president here during the brief period when New York was the nation’s capital.

As noted previously, the site of his swearing-in is prominently memorialized at Federal Hall, as you would expect. But, spurred on by the fact that this article I’m writing is for the White House History Quarterly, I realized I had no idea where George Washington lived during his time in New York. It seemed odd that I had never come across anything about his presidential residence—what would have essentially been our nation’s first White House.

What I learned is that he lived in two different presidential mansions during his time here, neither of which is still standing today. The first one was located at 1 Cherry Street (some say 3 Cherry Street), an address that ceased to exist when the Brooklyn Bridge was constructed on top of it. The only thing suggesting the symbolic importance of this location today is a brass tablet affixed to the bridge in 1899 by a chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

I had never noticed this tablet before. Being a plaque aficionado, my pride was a bit wounded when I learned I had overlooked it. After a little more digging around, I discovered the exact location of the marker: it’s mounted on the stone anchorage of the bridge on the south side of Pearl Street. For the entirety of my walk, more than a decade now, this tablet has been hidden behind construction fencing. top below right below

So I head out to Pearl Street once again. Knowing precisely where to look now, I can see the brass tablet from outside the fencing, although it’s unreadable at this distance. While I’m gawking at the bridge, a grumpy construction worker passes through a gate in the fence and gruffly tells me I’m blocking his way. I start enthusiastically explaining why I’m here—America’s first White House! The most significant George Washington Slept Here of them all! But he completely ignores me and slams the gate in my face.

A minute later, another worker opens the gate. He’s much friendlier and politely listens as I explain, probably sounding like a fevered crackpot, that this is where the first president of the United States lived. I plead with him to let me step inside the fence for ten seconds so I can take a photo of the plaque. He apologizes and tells me he can’t allow me in, for liability reasons, but he offers to take my phone and snap a photo for me. A pretty good compromise! Our government could use more people like this guy.

On Day 3,800, almost a decade after first passing the location, Matt finally spotted a brass tablet mounted on the stone anchorage supporting the Brooklyn Bridge. The plaque identifies the location of the first presidential mansion, George Washington’s home on Cherry Street. The tablet was installed by the Mary Washington Colonial Chapter in 1898, but construction barriers have made it inaccessible for the many years of Matt’s walk.

On Day 1,405, Matt crossed paths with President Washington again when he walked the service road of the Long Island Expressway. Along the route he photographed this plaque, which explains that Washington traveled the road on his tour of Long Island in 1790.

After crossing the Long Island Expressway and entering Alley Pond Park, Matt discovered the “Queens Giant,” a majestic, towering tulip poplar tree believed to be at least 400 years old. Matt was struck by the fact that it would have been standing tall when Washington visited the area himself. Today it is a living witness to the history Matt has encountered on his own journey through New York.