12 minute read

Al Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner

Nearly every four years between 1960 and 2016, the Waldorf-Astoria welcomed the presidential nominees from both parties to a white-tie fundraiser to honor the legacy of the former Governor of New York, Al Smith, in support of Catholic charities.

An

essay titled

“A Home away from Home.”68 LATER PRESIDENTS AT THE WALDORF

The Waldorf’s connection to the White House extended beyond Hoover and Apartment 31A. In the Waldorf Towers, U.S. presidents often used Apartment 35A, or “The Presidential Suite.” To be certain, visiting heads of state and other VIPs stayed there, but America’s commander in chief had first claim on it. In 1958, Eisenhower’s sudden decision to address the United Nations forced Secretary of State John Foster Dulles to vacate the suite and move into accommodations one floor up.71 Apartment 35A functioned as a White House away from the White House. It had four bedrooms, four bathrooms, a dining room, and a drawing room with a fireplace. Patriotic accents abounded. In 1962, one saw eighteenth-century–style American and British furniture—and a rocking chair modeled after President Kennedy’s. There was “Scenic America” wallpaper in the drawing room and cornices “with gold stars and eagles” in the dining room. Yellow tones dominated the master bedroom, a reminder of the color-specific rooms in the White House.69 Several presidents contributed to its decor. There were “eagle wall sconces” from Nixon, an “eagle desk set” from Jimmy Carter, and an “eagle-based table” from Ronald Reagan.70 The hotel efficiently adapted to a president’s presence. Offices adjacent to the lobby became press rooms equipped with typewriters and telephones.71 Every president from FDR to Barack Obama set up shop in Apartment 35A. Although Kennedy preferred to stay at the Carlyle Hotel, he held meetings in the Waldorf’s Presidential Suite.72

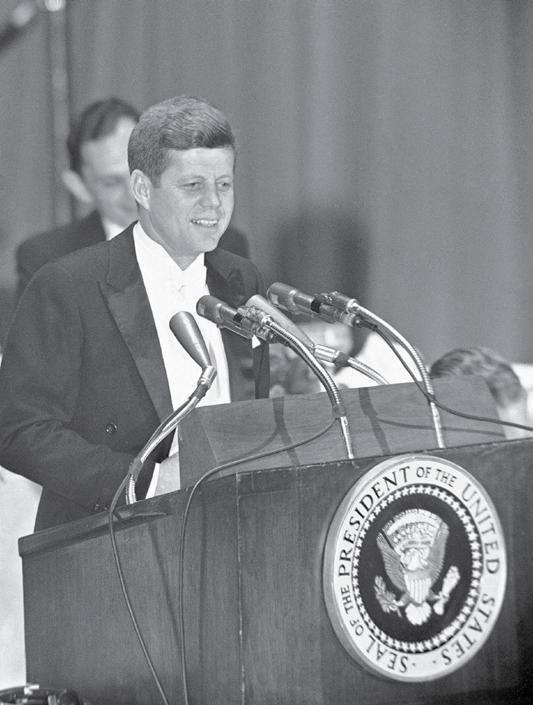

Presidential appearances remained an important part of life at the Waldorf. During one week in 1963, the hotel hosted two presidents. At separate events, Eisenhower received awards from the United Pilgrims of America, an “Anglo-American unity” outfit, and the American Iron and Steel Institute, which heralded Ike’s contributions to “the strengthening of individual enterprise.” Days afterward, six hundred Democratic Party donors gathered in the Empire Room for a birthday salute to JFK.73 Only a few months later, Eisenhower was at the hotel when news broke that Kennedy had been assassinated. Ike emerged from the Waldorf to express his condolences to Kennedy’s family. He condemned the “despicable act” that took the president’s life and predicted that Americans would stand united behind their government.74

A year later, however, Eisenhower sounded a different note. During a luncheon at the Waldorf, he assailed deficit spending, “doles” to poor people, public power projects, and moves “toward Federal domination over almost every phase of our economy.” The salvos—from a moderate Republican— surprised the audience, an assemblage of insurance executives. “It was as if Barry Goldwater were talking himself,” one man observed.75 Such rhetoric signified the growing clout of the GOP’s right wing as well as America’s widening political divide.

Brief breaks from partisan rancor occurred at the Al Smith Memorial Foundation Dinner, held annually at the Waldorf. Every four years between 1960 and 2016, the nominees of both parties attended the white-tie event to honor Smith’s legacy, raise funds for Catholic charities, and trade friendly barbs. In 1968, the retiring president stole the show. Paraphrasing a famous lament by Nixon— seated nearby—LBJ joked: “Pretty soon you won’t have Lyndon Johnson to kick around anymore.”76 First ladies have joined in the fun. At the 1989 dinner, Barbara Bush’s self-deprecating wit took center stage. “At last,” she said, “I get a chance to prove that I’m more than just a pretty face.”77 In 2000, her eldest son ribbed the dinner’s attendees. “This is an impressive crowd—the haves and the have-mores,” George W. Bush deadpanned. “Some people call you the elite; I call you my base.”78 The line provided fodder for Michael Moore, who included it in his antiwar film Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004). Perhaps the most gracious comments at the Al Smith Dinner came in 2008, when John McCain praised Barack Obama’s “impressive” political skills and wished his Democratic rival well.79

Presidential speeches at the Waldorf often raised hopes or sparked unrest. Few politicians stirred greater passions than Nixon, who enjoyed a long association with the hotel. In a speech at the Waldorf in 1953, Nixon outlined this thinking on domestic affairs. He disparaged the welfare state, which “absorbs the citizens and private groups” via “cradle to grave” regulations. The vice president professed instead his belief in the “general welfare state” that “seeks to help, not control” the “free energies of labor, business and the farmer.”80 Revisionist historians have traced Nixon’s moderate ideology, and policies, to this address.81 In 1968, Nixon delivered his first remarks as president-elect from the Waldorf’s Grand Ballroom. The “great objective” of his administration, he proclaimed, was “to bring the American people together.”82 To a country rent over race, civil rights, crime, and the Vietnam War, such words offered little more than a salve. The war in Vietnam continued, as did criticism of it. In 1966, four thousand demonstrators had picketed a Johnson speech at the Waldorf; they chanted “war on poverty, not people” and carried Viet Cong flags, along with a large “Impeach LBJ” sign.83 Three years later, three thousand antiwar activists clashed with police near the Waldorf, where Nixon was attending the National Football Foundation’s dinner. They had assembled, they claimed, “in answer to the President’s recent television appeal for the ‘silent majority’ to speak up.”84 Presidents came and went and the issues changed, but protest at the hotel endured. In 1990, members of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) infiltrated the Waldorf while President George H. W. Bush spoke at a GOP fund-raiser. They voiced disapproval of Bush’s response to the AIDS epidemic by staging “die-ins” in the hotel’s lobby and unfurling a banner that demanded, “READ OUR LIPS: AIDS ACTION NOW.” The demonstration overshadowed Bush’s speech and was light-years removed from the quiet evenings Herbert Hoover had spent with compatriots in Apartment 31A.85

THE WALDORF IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

The twenty-first century brought change to the hotel Hoover once called America’s “Guest House.”86 In 2014, a Chinese insurance company purchased the Waldorf-Astoria and made plans to transform the building into condominiums and a boutique hotel. Shortly thereafter, President Obama declined to stay at the hotel, citing “security concerns.” “Its glory days had passed,” the historian David Freeland acknowledged.87 The final Al Smith Dinner at the Waldorf, in 2016, marked the end of an era. Hillary Clinton and Donald J. Trump jibed each other, but many guests thought that Trump went too far and they booed him.88 Trump’s candidacy, and election, brought attention to hotels and commercial real estate owned by a president. Trump Tower, the Manhattan skyscraper that was Trump’s business headquarters and home, eclipsed the Waldorf, which closed for renovation in 2017. Yet the next chapter remains to be written. The Waldorf’s eventual reopening may bring renewed ties between the presidency and an iconic landmark.

Notes

1. Herbert Hoover, “Radio Remarks on the Opening of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel,” September 30, 1931, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Herbert Hoover (1931) (Washington, D.C.: United States Printing Office, 1976), 447.

2. David Freeland, American Hotel: The Waldorf-Astoria and the Making of a Century (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2021), 297.

3. “Waldorf Boom Row Is Growing Rapidly,” New York Times, June 19, 1924, 3.

4. Hubert H. Humphrey, The Education of a Public Man: My Life and Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991), 178.

5. Freeland, American Hotel, 278–79; “The Mondale Way to the Presidency,” Wall Street Journal, February 22, 1983, 30.

6. Eleanor Roosevelt, “My Day,” December 6, 1950, Eleanor Roosevelt Papers, Digital Edition, George Washington University website, www2.gwu.edu.

7. “Candidates, Ike Aid ‘War’ On Bigotry,” Washington Post, October 27, 1960, A11.

8. Eleanor Roosevelt, speech, October 26, 1960, folder Transcripts of Eleanor Roosevelt’s Appearances on Behalf of JFK, 1960 [1 of 3], box 15, series 4: Campaigns, 1960–1980, Abba P. Schwartz Personal Papers, John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, Mass.

9. “Excerpts From Address Here by Senator Goldwater,” New York Times, January 16, 1964, 21.

10. “Goldwater Urges Study of the Poor,” New York Times, January 16, 1964, 21.

11. “Johnson Pledges Restraint Abroad and in Race Issue,” New York Times, August 13, 1964, 1.

12. Dean Kotlowski, “The Presidents Club Revisited: Herbert Hoover, Lyndon Johnson, and the Politics of Legacy and Bipartisanship,” Historian 82, no. 4 (2020): 482–83.

13. Joseph P. Binns, oral history interview by Raymond Henle, October 10, December 2, 1968, transcript, 25, Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa.

14. W. A. Doerr to Roy W. Howard, October 4, 1939, folder 1939 City File—New York—Herbert Hoover Interview, box 154, Roy W. Howard Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

15. Irwin Hoover, undated notes, folder White House Herbert Hoover, box 6, Irwin H. Hoover Papers, Library of Congress.

16. Daniel Rodriguez, oral history interview by Robert Cubbedge, February 10, 1971, transcript, 19–20, Hoover Library.

17. “Truman Is Recalled Here for Warmth and Simplicity That Had Wide Appeal,” New York Times, December 28, 1972, 25.

18. Hoover, “Speech on the Occasion of the 20th Anniversary of the Opening of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel,” November 5, 1951, file 3332, Herbert Hoover Special Collections—Articles, Addresses and Public Statements, 1915–1964, Hoover Library.

19. Freeland, American Hotel, 80.

20. Joan Hoff Wilson, Herbert Hoover: Forgotten Progressive (New York: HarperCollins, 1975), 279.

21. Herbert Hoover, The Crusade Years, 1933–1955: Herbert Hoover’s Lost Memoir of the New Deal Era and Its Aftermath, ed. George H. Nash (Stanford, Cal.: Hoover Institution Press, 2013), 51–328.

22. James A. Farley, oral history interview by Raymond Henle, December 7, 1966, transcript, 29, Hoover Library.

23. Hoover, “Remarks at the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel,” September 28, 1956, file 3756, Herbert Hoover Special Collections, Hoover Library.

24. Kotlowski, “Presidents Club Revisited,” 469–71, 483–85.

25. Hoover, Crusade Years, 11–13.

26. Herbert Hoover to Oscar Tschirky, November 16, 1932, file 2057, Herbert Hoover Special Collections, Hoover Library.

27. George H. Nash, Herbert Hoover and Stanford University (Stanford, Cal.: Hoover Institution Press, 1988), 57–59, 118; Nancy Beck Young, Lou Henry Hoover: Activist First Lady

(Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 183–85.

28. Fio Dell’agnese, oral history interview, with Raymond Henle, October 7, 1968, transcript, 7 (“lovely’) and 5 (“permanent guest’), Hoover Library.

29. Hoover to Lucius Boomer, June 29, 1940, folder 2216 (2), box 20, Herbert Hoover Post-Presidential Papers: Individual File, Hoover Library.

30. Hoover to Joseph P. Binns, February 1, 1952, October 2, 1952, March 13, 1954, April 11, 1955, September 6, 1955, October 2, 1956, and October 17, 1956, folder 2189 (1), box 18, Hoover PostPresidential Papers: Individual File, Hoover Library.

31. Nonunion employees objected to a contract that prevented them from continuing their health insurance upon retirement or the end of their employment at the Waldorf. Hoover to Binns, October 29, 1955, folder 2189 (1), box 18, Hoover PostPresidential Papers: Individual File, Hoover Library.

32. N. Loyall McLaren essay, “Herbert Hoover’s Welcome into the Old Guard,” August 25, 1967, attached to N. Loyall McLaren, oral history interview by Raymond Henle, November 5, 1967, Hoover Library.

33. Quoted in Hoover, Crusade Years, 12.

34. Rodriguez oral history, 2, 10–19, 28–32; M. Elizabeth Dempsey, oral history interview by Raymond Henle, July 13, 1967, transcript, 27, 29, 40, quotation on 37, Hoover Library.

35. Quoted in Michael J. Le Pore, oral history interview by Raymond Henle, December 5, 1966, transcript, 50–51, Hoover Library.

36. Charles Edison, oral history interview by Raymond Henle, December 6, 1966, transcript 13, Hoover Library.

37. Quoted in “Joe Garagiola Broadcast on NBC,” October 22, 1964, folder Hoover Funeral, box 182, Hoover Post-Presidential Papers: Subject File, Hoover Library.

38. Dempsey oral history, 17.

39. “Remarks by Honorary Commodore Herbert Hoover, Key Largo Anglers Club Induction of Flag Officers,” March 3, 1961, attached to J. Clinton Campbell, oral history interview by Raymond Henle, April 15, 1967, Hoover Library.

40. Hoover to Jorgine Boomer, March 28, 1962, folder 2217 (2), box 20, Hoover Post-Presidential Papers: Individual File, Hoover Library.

41. Rodriguez oral history, 33.

42. Rudolph N. Schullinger, oral history interview by Charles T. Morrissey, October 27, 1968, 11; Dempsey oral history, 1; Bernice Miller, oral history interview by Ray [Raymond?] Henle, December 7, 1966, 10, all Hoover Library. See these books by Hoover: The Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1958); Fishing for Fun: And to Wash Your Soul (New York: Random House, 1963); Herbert Hoover on Growing Up: His Letters from and to American Children, ed. William Nichols (New York: William Morrow, 1962); Freedom Betrayed: Herbert Hoover’s Secret History of the Second World War and Its Aftermath, ed. George H. Nash (Stanford, Cal.: Hoover Institution Press, 2011).

43. Hoover to Henry J. Taylor, January 20, 1945, folder Herbert Hoover Correspondence, 1923–1929, box 1, Loretta Camp Frey Papers, Hoover Library; Herbert Hoover, The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: The Great Depression, 1929–1941 (New York: Macmillan, 1952), 2–28, 161–66.

44. Richard Norton Smith, An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984), 406.

45. John D. M. Hamilton, “Visit with Mr. Hoover,” July 27, 1955, folder Visit with Mr. Hoover 7/27/55, 3/9/56, and 6/860, box 15, John D. M. Hamilton Papers, Library of Congress.

46. Farley oral history, 5–8; Dell’agnese oral history, 10; Kotlowski, “Presidents Club Revisited,” 470–73.

47. Herbert Hoover quoted by Richard Nixon in “Frank Gannon’s interview with Richard Nixon,” September 7, 1983, part 1, Oral History Collections, University of Georgia Special Collections Libraries, Athens, Ga., online at https://georgiaoralhistory.libs. uga.edu.

48. Smith, An Uncommon Man, 403–31.

49. Quoted in “31st President Achieved Prominence in Four Major

Careers During His Lifetime,” New York Times, October 21, 1964, 40.

50. Herbert Hoover, speech, July 25, 1960, folder Hoover, Herbert and Family, 1948–69, box 33, James A. Farley Papers, Library of Congress.

51. Rodriguez oral history, 9.

52. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor to Richard E. Berlin, October 22, 1964, folder Condolences, 1963–1966, box 4, Herbert Hoover Death and Funeral Collection, Hoover Library.

53. James A. Farley to Allan Hoover, March 5, 1965, folder Condolences—Responses, 1964–1965 (6 of 6), box 4, Herbert Hoover Death and Funeral Collection, Hoover Library.

54. Farley to Allan Hoover, November 6, 1964, folder Hoover, Herbert and Family, 1948–69, box 33, Farley Papers.

55. Edison oral history, 9.

56. Dempsey oral history, 33.

57. Rodriguez oral history, 31.

58. Binns oral history, 8–9.

59. Hoff Wilson, Herbert Hoover, 231.

60. Mrs. John A. Brown, oral history by Raymond Henle, December 6, 1966, 9, Hoover Library.

61. Dell’agnese oral history, 15.

62.“Herbert Hoover,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 21, 1964, folder Hoover Death Clips USA Region 2, box 3, Hoover Death and Funeral Collection; “Herbert Hoover,” Dallas Morning News, October 21, 1964, and “Hoover Marked His Service,” San Angelo (Tex.) Standard-Times, October 21, 1964, both folder Hoover Death Clips USA Region 7, box 3, Herbert Hoover Death and Funeral Collection, Hoover Library.

63. “Herbert Hoover,” Washington Post, October 21, 1964, A20; “Herbert Hoover,” Buffalo Evening News, October 21, 1964, folder Hoover Death Clips USA Region 2, box 3, Herbert Hoover Death and Funeral Collection, Hoover Library.

64. Stephen Skowronek, The Politics Presidents Make: Leadership from John Adams to Bill Clinton (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1997), 261.

65. John Bartlow Martin, review Herbert Hoover: A Public Life, by David Burner, Social Practice (Winter–Spring 1979), 91, copy in folder 8, box 203, John Bartlow Martin Papers, Library of Congress.

66. Belfast Telegraph, October 21, 1964, folder Clips Europe British Isles, box 1, Herbert Hoover Death and Funeral Collection, Hoover Library.

67. “The Restoration of Herbert Hoover,” Wall Street Journal, August 5, 1974, 10.

68. Herbert Hoover, “A Home away from Home” [1939], folder 2216 (2), box 20, Hoover Post-Presidential Papers: Individual File, Hoover Library.

69. “Presidential Suite of Waldorf Towers Is Redecorated with an Eye to Color,” New York Times, April 18, 1962, 59.

70. Scott Mayerowitz, “Behind the Scenes at the Waldorf Astoria’s Posh Presidential Suite,” posted September 21, 2009, ABC News website, https://abcnews.go.com.

71. “Dulles Loses Presidential Suite As Waldorf Protocol Takes Over,” New York Times, August 13, 1958, 3.

72. “Presidential Suite of Waldorf Towers.”

73. “Waldorf Faces Job of Planning Fetes for 2 Presidents,” New York Times, May 21, 1963, 62.

74. Quoted in David Eisenhower with Julie Nixon Eisenhower, Going Home to Glory: A Memoir of Life with Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961–1969 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010), 120–21.

75. “Eisenhower Hits at Federal Doles,” New York Times, December 10, 1964, 29.

76. “Johnson Shares Dais Here with Nixon and Humphrey,” New York Times, October 17, 1968, 1.

77. “The Keynote Quipster: Mrs. Bush at New York’s Al Smith Dinner,” Washington Post, October 20, 1989, B1, B9.

78. “Presidential Rivals Feast on Jokes, Jabs,” Washington Post,

October 20, 2000, A9.

79. John McCain, remarks at 2008 Al Smith Dinner, posted August 18, 2018, NBC News website, www.nbcnews.com/video.

80. “Text of Vice President Nixon’s ‘Report From Washington’ Speech to Publishers’ Convention,” New York Times, April 24, 1953, 20.

81. Joan Hoff, Nixon Reconsidered (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 116.

82. “Transcript of the Statement by Nixon Pledging to ‘Bring America Together,’” New York Times, November 7, 1968, 21.

83. “4,000 Picket Johnson in Antiwar Protest at Hotel,” New York Times, February 24, 1966, 16.

84. “63 Arrested, 8 Policemen Hurt As 3,000 Protest Nixon’s Visit,” New York Times, December 10, 1969, 1.

85. Freeland, American Hotel, 288, 285, 289.

86. Hoover, “Remarks at the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.”

87. Freeland, American Hotel, x.

88. “2016 Al Smith Dinner (Full) The New York Times,” video on YouTube, www.youtube.com.