Please note that the following is a digitized version of a selected article from White House History Quarterly, Issue 77, originally released in print form in 2025. Single print copies of the full issue can be purchased online at Shop.WhiteHouseHistory.org

No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

All photographs contained in this journal unless otherwise noted are copyrighted by the White House Historical Association and may not be reproduced without permission. Requests for reprint permissions should be directed to rights@whha.org. Contact books@whha.org for more information.

© 2025 White House Historical Association.

All rights reserved under international copyright conventions.

may 8, 1945—V-E Day—marked Victory in Europe. Germany’s surrender brought triumph to the Allies and a sense of relief that reverberated around the world. The White House, the symbolic heart of the American presidency, was at the center of it all. In the years leading up to that day, its walls had witnessed the weight of war, the resilience of leadership, and the sacrifices made on both the battlefield and the home front. If these walls could talk, they would tell the story of how the White House shaped, and was shaped by, World War II.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt was intimately tied to the events of World War II. He had led the nation through the Great Depression, and when war erupted in Europe, he navigated the delicate balance of aiding the Allies while maintaining official neutrality. That changed on December 7, 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. The next day, FDR stood before Congress in the Capitol and delivered his famous “Day of Infamy” speech, leading the nation into war.

The White House became a wartime command center. The Map Room—still in use today for meetings of all kinds—was created as a top-secret intelligence hub where FDR could receive real-time updates on the war’s progress. Winston Churchill was a frequent guest, staying at the White House

Could

STEWART D. M C LAURIN PRESIDENT WHITE HOUSE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

multiple times, including just after Pearl Harbor. Churchill and Roosevelt, often meeting in the Oval Office or even late at night in the president’s Private Quarters, forged the critical alliance that would lead to victory.

Eleanor Roosevelt was equally influential. The first lady expanded her advocacy, traveling extensively to visit troops, meeting with wounded soldiers in hospitals, and reporting back on conditions overseas. In 1942, she toured England, bringing words of encouragement from the White House to bomb-ravaged Londoners. The next year she visited troops in the Pacific. he East Room of the White House, which had long served as a venue for grand state occasions, took on a different role in wartime, hosting blood drives, military ceremonies, and even simple gatherings where Mrs. Roosevelt met with servicemen’s families.

Eleanor Roosevelt was also influential. the

year she visited troops in the Pacific. The East gather Germany’s

When news of Germany’s surrender reached Washington, celebrations erupted. Thousands flooded Pennsylvania Avenue, gathering outside the White House. President Roosevelt did not live to see the victory he had worked so hard for; he had died just weeks earlier, on April 12, 1945. The weight of the war’s final chapter fell to his successor, Harry S. Truman.

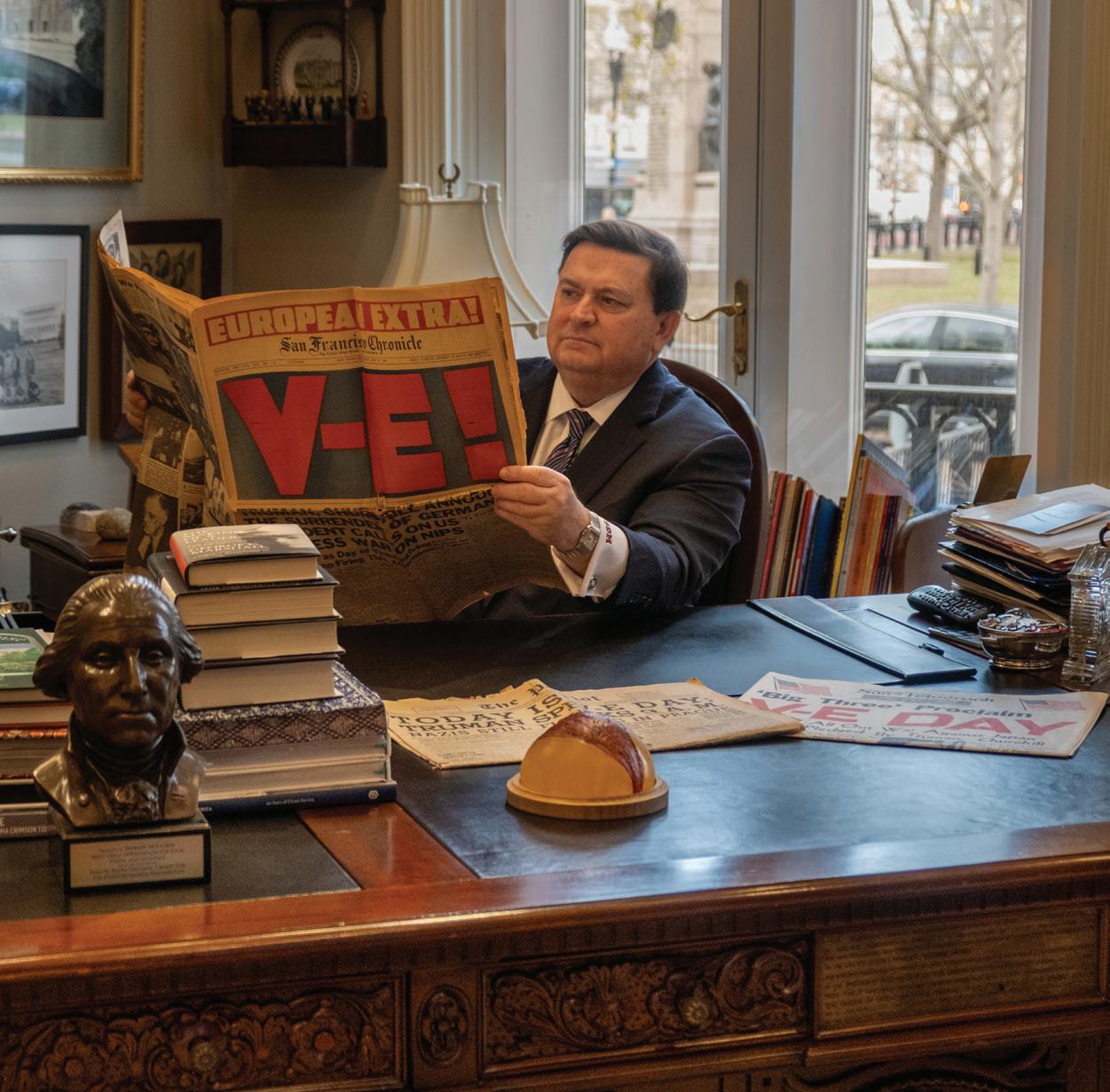

Stewart D. McLaurin reads the news of the Victory in Europe, May 8, 1945, as the eightieth anniversary of V-E Day approaches, 2025.

Inside the White House, Truman marked the moment with characteristic humility. In a brief radio address, he declared V-E Day “a solemn but glorious hour.” He reminded Americans that the war was not over; Japan still had to be defeated. It was also his birthday, but when staff suggested celebrating, he refused. “I only wish Franklin Roosevelt had lived to witness this day,” he said.

While Roosevelt and Truman led from the White House, several future presidents were fighting on the front lines. World War II produced a generation of leaders who would later bring their battlefield experience into the Oval Office.

Dwight D. Eisenhower was the supreme allied commander in Europe, overseeing the D-Day invasion and masterminding the campaign that led to Germany’s defeat. Just eight years after the war, in 1953, he would enter the White House as president, bringing a soldier’s perspective to Cold War tensions.

Future president General Dwight D. Eisenhower addresses the “The Screaming Eagles,” the 101st Airborne Division, as they prepare to join the Allied invasion of Europe, D-Day, June 6, 1944.

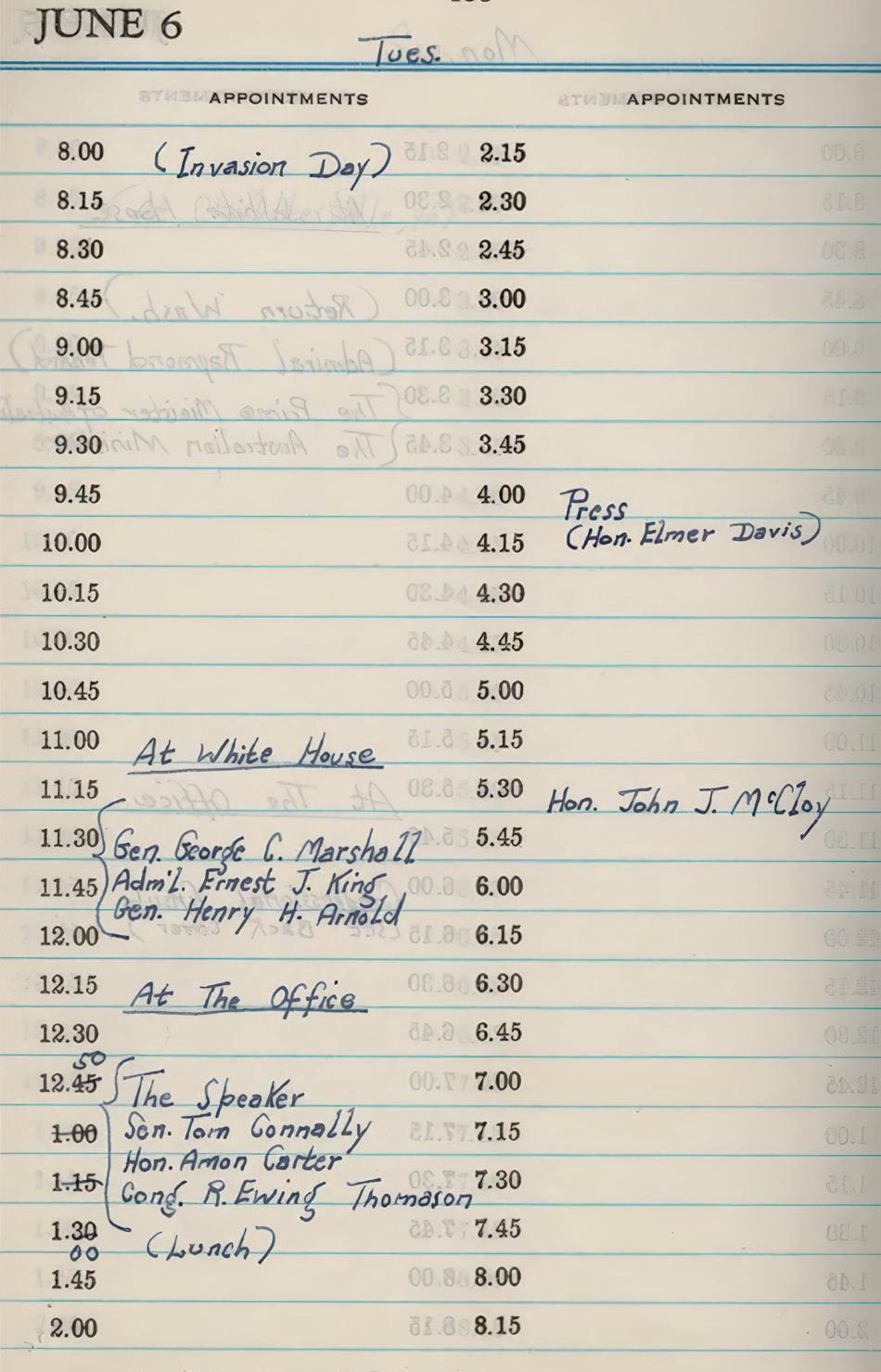

President Franklin Roosevelt’s busy calendar for the same day opens with the notation “(Invasion Day).” In the morning the president met with General George C. Marshall, Admiral Ernest J. King, and General Henry H. Arnold. In the afternoon he met with Speaker of the House Sam T. Rayburn, Senator Tom Connally, Amon Carter, publisher of the Fort Worth Star Telegram, and Congressman R. Ewing Thomason. At 4:00 p.m. he met with the press. Although not noted on his appointment calendar, at 10:07 p.m. he made a radio broadcast from the Diplomatic Reception Room assuring the nation that the invasion “has come to pass with success thus far” before delivering his “Prayer on the Invasion of Normandy.”

John F. Kennedy, a young naval officer, served heroically in the Pacific, commanding PT-109. His vessel was struck by a Japanese destroyer, but he led his crew to safety, demonstrating the leadership that would later define his presidency.

Lyndon B. Johnson served in the navy as a lieutenant commander. Though a sitting congressman at the time, he volunteered for active duty and received the Silver Star for his service in the Pacific.

His congressman politi-

Richard Nixon was a navy lieutenant who managed logistics and supply operations in the Pacific theater. His wartime service shaped his political rise and his understanding of global military strategy.

Gerald Ford served aboard the aircraft carrier USS Monterey in the Pacific, surviving typhoons and intense combat missions. His experiences gave him a deep respect for military service, which he carried into his presidency.

Ronald Reagan drew on his acting experience while serving in the Army Air Force, making training films during the war.

while serving in the Army Air Force, making trainlater, as the forty-first president, his military service symbol of national unity and sacrifice. Rationing curtains over dows to guard against potential air raids. The functional

George H. W. Bush, the youngest navy pilot at the time, flew fifty-eight combat missions over the Pacific. Shot down over the ocean, he was rescued by an American submarine, receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross for his bravery. Decades later, as the forty-first president, his military service informed his leadership during the Gulf War.

During World War II, the White House was more than the home and office of the president: it was a symbol of national unity and sacrifice. Rationing meant fewer formal dinners, and blackout drills were routine, with thick curtains drawn over windows to guard against potential air raids. The White House gardens, typically a place of beauty, became functional as Eleanor Roosevelt championed Victory Gardens to encourage Americans to

minister and the ambassador of Poland, the under state,

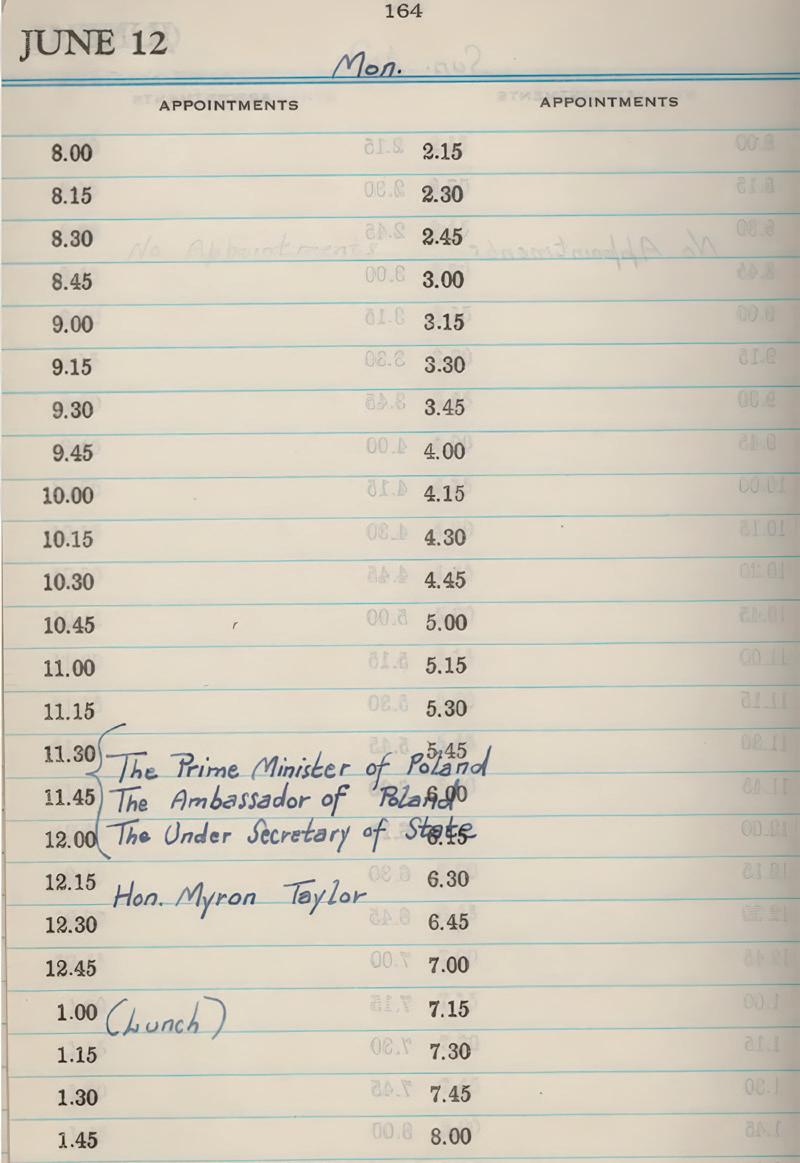

On June 12, 1944, future President John F. Kennedy is presented with a medal for his heroism in saving his surviving crew members following the sinking of PT-109. The medal is presented by Captain Frederick L. Conklin, the commandant, Chelsea Naval Hospital, Chelsea, Massachusetts. On this same day at the White House, President Franklin Roosevelt met with the prime minster and the ambassador of Poland, the under secretary of state, and Myron Taylor, FDR’s personal representative to Pope Pius XII.

grow their own food. The White House lawn even saw a small vegetable patch as part of the effort.

Security was heightened. Antiaircraft guns were positioned near the White House, and sandbags were stacked around the building’s perimeter. The war also changed daily life inside. The number of household staff was reduced as many joined the military effort. First families adapted, living with the same shortages and restrictions as the rest of the nation.

The White House has stood through war and peace, its walls bearing silent witness to history. In World War II, it was a place of decision-making, diplomacy, and determination. If these walls could talk, they would recount the urgent briefings and decisions in the Map Room, the late-night conversations between Roosevelt and Churchill, the

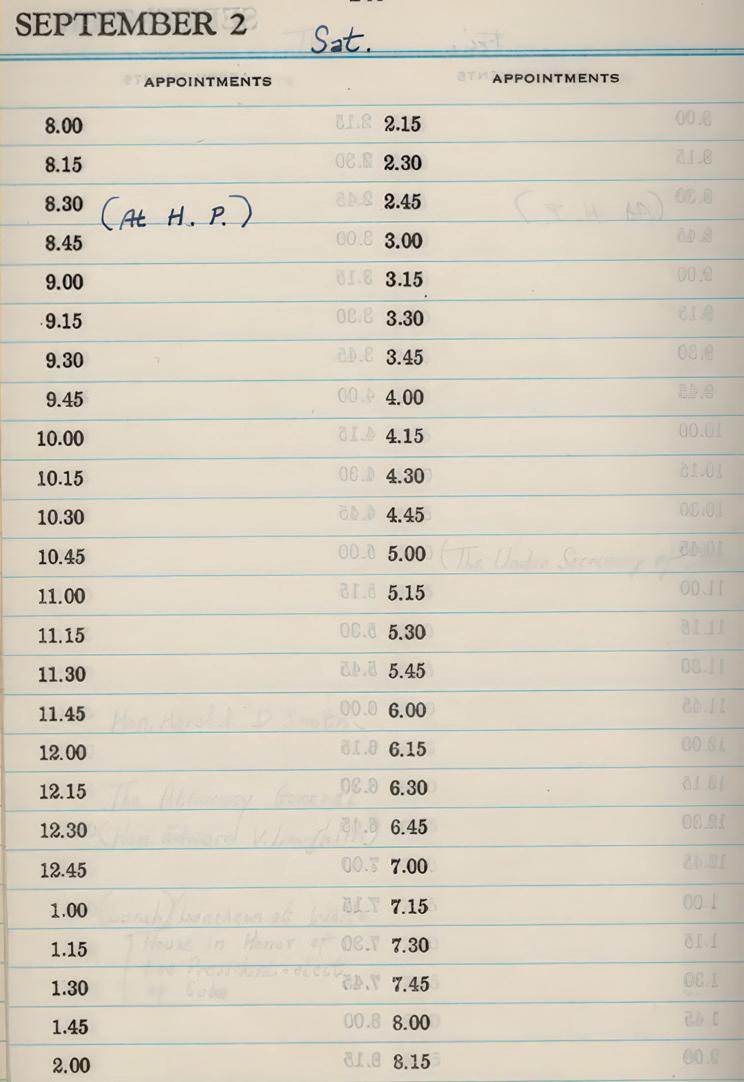

On September 2, 1944, future President George H. W. Bush is rescued after bailing out of his torpedo bomber and into the Pacific Ocean. He was shot down during a bombing mission. This grainy photo captures the action as the crew of the submarnie USS Finback prepares to pull Bush from a lifeboat. While the drama unfolded in the Pacific, President Roosevelt was in Hyde Park, and it was a quiet day at the White House.

quiet resilience of Eleanor Roosevelt as she penned another letter of condolence to a grieving family. They would recall Truman’s solemn words on V-E Day and the celebrations just beyond its gates.

Today, the White House remains a living symbol of the presidency and the nation’s endurance. The echoes of those wartime years still linger, reminding us of the sacrifices made and the leadership that guided the country through its darkest hours. As we remember V-E Day, we also remember the role of the White House—not just as the home of presidents but as a witness to history, a place where the course of the world was shaped and where the promise of peace was ultimately fulfilled in that great World War.