22 minute read

Before the WHITE HOUSE New York’s Capital Legacy

THOMAS J. BALCERSKI

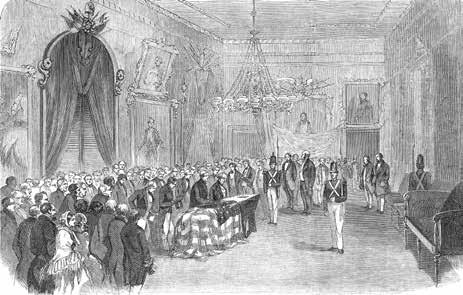

on april 30, 1789, George Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States of America. On the streets below, crowds gathered to witness Washington, his hand placed on a Bible, be sworn in from a balcony at Federal Hall in New York City. After taking the Oath of Office, Washington supposedly added the words “So help me God” and kissed the holy book. Following the ceremony Washington delivered an Inaugural Address to the members of Congress, then attended services at St. Paul’s Chapel. That evening fireworks illuminated the sky. The future of New York City—and the nation—never looked brighter.

It had been a long road getting to this point. Between 1775 and 1785, first the Continental Congress and then the Confederation Congress had met temporarily in seven different cities, namely Philadelphia, Baltimore, Lancaster, York, Princeton, Annapolis, and Trenton.2 Adding to its difficulties, Congress was sharply divided over the permanent home of the capital, split between those who wanted a central inland location and those who favored an established seaboard city.3

New York had been devastated by seven years of British occupation, including two great fires that had burned extensive swaths of the city in September 1776 and again in August 1778. But the city’s fortunes had slowly improved following the British evacuation on November 25, 1783 (a date celebrated for decades by the city’s residents as “Evacuation Day”), such that by 1790, the diverse population had grown to 40,000, of which 2,500 were enslaved people.4 In 1784, Chancellor Robert Livingston and the New York State Legislature beseeched the beleaguered Congress to select New

York as its next meeting place.5 Abandoning a plan to create two capitals, Congress voted unanimously on December 23, 1784, to relocate from the French Arms Tavern in Trenton to “the city of New York.”6

Once in New York, the outgoing Confederation Congress set about passing important legislation, including the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which provided for the organization of the Ohio country and notably excluded slavery from the territory.7 Congress also continued debating the relative merits of various sites for the permanent capital. In Philadelphia, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 failed to resolve the question and eventually voted to keep “the present Seat of Congress.”8

In September 1788, the Confederation Congress similarly voted to leave the seat of government in New York for the meeting of the new Congress, under the newly ratified Constitution, scheduled for March 4, 1789.9

New Yorkers eagerly prepared to celebrate the changeover to the new government. At midnight on March 3, thirteen cannons were fired from Fort left

New previous

Given a neoclassical facelift by Pierre L’Enfant, City Hall is seen here as it appeared when George Washington stood on the balcony to take the first presidential oath of office.

George in salute of the thirteen states leaving the old confederation. The next day, flags were flown and church bells rang, but only eleven cannons fired in honor of those states that had already ratified the Constitution (North Carolina would not ratify the document until November, while Rhode Island held out until May 1790).10

New York had come to embrace its place as the nation’s capital.11 Previously, the Confederation Congress had been offered meeting space in City Hall as well as additional rooms at the tavern kept by Samuel (“Black Sam”) Fraunces at Broad and Pearl Streets.12 Then, on September 17, 1788, the Common Council of New York City resolved to give over City Hall for the exclusive use of the new federal government. The council commissioned Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the French émigré and

Continental Army soldier, to redesign the ancient building (constructed in 1700) into an edifice worthy of the seat of a republican government.13 Work began on October 6, 1788, and continued through April 8, 1790. L’Enfant’s efforts transformed the old Queen Anne facade by applying a neoclassical facelift, replete with an open balcony topped by a bald eagle. The impressive result left one congressman wondering if the building, now known as Federal Hall, was a “trap to catch the Southern men” into staying permanently in New York.14

But many questions remained about the future of the federal government. Most critically, when would George Washington, the newly elected president and “Father of His Country” arrive to take up his new office? And, perhaps equally as important, where would he live?

The First Presidential Mansion

When Congress convened in New York City, its members were expected to lodge in private residences, or boardinghouses, at their own expense.15 As a notable exception to this rule, the Confederation Congress provided furnished quarters for its president at the expense of the government. Since January 1788, the office had been filled by Cyrus Griffin of Virginia, who, following in his predecessor’s footsteps, lived at a large three-story home at No. 3 Cherry Street located about sixtenths of a mile from Federal Hall at St. George’s Square (later Franklin Square).16

The house was situated on land once owned by Robert Benson, who had previously operated a brewery on the site. In 1770, Benson’s widow, Catherine Van Borsum, and her son Robert Benson, sold the plot to merchant Walter Franklin for £2,000. Franklin built a Georgian– style structure on the site with a front face of about 50 feet. In 1786, Franklin’s widow, Maria Bowne Franklin, married Samuel Osgood, a commissioner of the treasury whom Washington later appointed postmaster general. Accordingly, the home was variously known as the Walter Franklin House and the Samuel Osgood House.17

Nonetheless, George Washington was unclear just where he would stay as late as March 1789. Turning down an offer from New York governor George Clinton, Washington wrote James Madison on March 30 that he would “make it a point to take hired lodgings, or Rooms in a Tavern until some house can be provided.” Ultimately, he concluded, “it is my wish & intention to conform to the public desire and expectation, with respect to the style proper for the Chief Magistrate to live in.”18

Fortunately for Washington, Congress had turned its attention to the matter. On April 15, 1789, a joint committee of Congress—formed to plan the upcoming Inauguration—determined to renew the lease on the house at No. 3 Cherry Street for use by the new president. The committee resolved “That Mr. Osgood, the proprietor of the house lately occupied by the President of Congress, be requested to put the same house and furniture thereof in proper condition for the residence and use of the President of the United States.”19 The Franklin House—described by the French minister the Comte de Moustier as a “humble dwelling”—was leased for £845 a year, with another £8,000 expended to upgrade the home.20 Coincidentally, Washington’s next-door neighbor, at No. 5 Cherry Street, would be John Hancock, himself a former presiding officer of the Confederation Congress.21

The first President’s House on Cherry Street, in Manhattan, as it appeared in 1800. President George Washington lived here from April 23, 1789 until February 23, 1790.

Congressional absenteeism had been the culprit in the delay to secure a residence for the incoming president. On March 4, 1789, the day appointed by the Confederation Congress for the start of the new government, only eight senators and thirteen representatives were present. A quorum finally emerged in the House on April 1, while five days later, the Senate achieved numbers sufficient to count the electoral votes cast for president.22 The next morning, Charles Thompson, secretary of Congress, set out for Mount Vernon to inform Washington of his election as president of the United States, which he did on the morning of April 14.23

Washington immediately prepared to leave for New York. Short of funds, he borrowed some £625 from neighbor Richard Conway to pay his travel expenses.24 All along the route people came out to witness Washington pass by. On April 23, 1789, Washington crossed the Hudson River on a large barge and was greeted by a committee composed of Governor George Clinton, Mayor James Duane, and officers of the city’s governing corporation. An elaborate parade of military officers, troops, elected officials, clergy, and citizens accompanied the president approximately one mile from the Battery to No. 3 Cherry Street.25

New York society paid particular attention to president’s new house. As Sarah Osgood Robinson, niece of Maria Osgood, wrote to her friend Kitty Wistar:

Uncle Walter’s house in Cherry Street was taken for him [Washington], and every room furnished in the most elegant manner. Aunt Osgood and Lady [Catherine Alexander] Duer had the whole management of it. I went the morning before the General’s arrival to look at it. The best of furniture in every room, and the greatest quantity of plate and china I ever saw; the whole of the first and second stories is papered, and the floors covered with the richest kind of Turkey and Wilton carpets. . . . There is scarcely anything talked about now but General Washington and the Palace.26

Not content with the furnishings at the Franklin House, Washington expended some £400 for glass and queensware and purchased bedsteads, chairs, knife boxes, washstands, clothespresses, and dining, tea, breakfast, and card tables.27 The efforts paid off, for upon her subsequent arrival Martha Washington found the house “handsomely furnished all new for the General.”28

The “Palace” was occupied by members of the Washington family and an array of household staff. Two Custis grandchildren—Eleanor (“Nelly”) Parke and George Washington (“Wash”) Parke—lived there. So did Tobias Lear, Washington’s personal secretary who supervised four additional secretaries, among them Thomas Nelson, nephew Robert Lewis, and political aide Colonel David Humphreys. Steward Samuel Fraunces oversaw a staff of white servants, which included a coachman, porter, cook, valet de chambre, maids, footmen, and laundresses.29

The Washington household also included seven enslaved African Americans from Mount Vernon: William (“Billy”) Lee, Washington’s longtime valet and body servant; Christopher Sheels, Lee’s nephew and later a body servant; Austin and Giles, both footmen; Paris, a stable hand; Molly, nursemaid to the Washington grandchildren; and Oney Judge, who later became famous for escaping from the president.30 Thus the staff of twenty-six outnumbered the four family members in residence at the Franklin House. It would be a pattern that carried over to future executive residences.

Even prior to settling his household, Washington participated in the first Inaugural Ball, called a “Public Ball and Entertainment.” The event had been pushed back by a week to allow for the arrival of Martha Washington, but when it became known that she would be delayed longer than expected, the ball went forward on May 7. With nearly three hundred people attending, all eyes were on the president, who danced two cotillions and a minuet. A week later, the French Minister de Moustier hosted a ball of his own.31

After Martha Washington arrived in the capital, she arranged a schedule of social events, most notably levees, dinners, and “drawing rooms” held each Friday from 7:00 until 9:00 in the evening.

George Washington attended the functions, without sword or hat, as he was in his capacity as the husband of the hostess and not as president of the United States.32 For its part, Congress voted after a prolonged debate that Washington be addressed simply as “the President of the United States,” without an additional title.33

President Washington also instituted the custom of holding “state dinners” each Thursday afternoon at 4:00 p.m. The gathering included “from ten to twenty-two” guests in addition to the president’s official “family,” which besides relatives included his secretarial staff. The meal tended toward “roast beef, veal, lamb, turkey, duck and varieties of game,” with silver-framed table ornaments adorned by “chaste mythological statuettes.”34 Beyond these formal social events, Washington also opened the house to the public twice per week on Tuesdays and Fridays, between 2:00 and 3:00 in the afternoon.35

Congress concluded its first session on September 29, 1789, with a strong record of legislative accomplishments, among them the introduction of amendments to the Constitution and the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1789.36 Hoping to strengthen the bonds of Union, Washington toured the New England states from October 15 to November 13, thus establishing regular travel as another function of the presidency.37 Washington’s first year at the Franklin House had proven a success. With the start of the new congressional session in January 1790, however, he determined to seize the first opportunity to upgrade the “Palace.”

The Second Presidential Mansion

Washington’s chance came when French Minister de Moustier returned home, vacating his “fine and commodious mansion” at No. 39 Broadway.38 Built in 1786–87, it was owned by the merchant Alexander Macomb, who gladly offered it to Washington at an annual rent of £2,500; while more expensive than the Franklin House, it was a story higher and featured a garden extending to the banks of the Hudson River. The larger dining room could seat between sixteen and twenty guests.39 All in all, the Macomb House, or the “Mansion House” as the building later became known, was considered the “finest private dwelling in the city” and conveniently located four blocks from Federal Hall.40

On February 23, 1790, Washington and his family relocated to the Macomb House.41 Upon agreeing to rent the house, Washington had surveyed the existing furniture and purchased several pieces left behind by de Moustier, including a writing desk and chair.42 From there, he arranged for the construction of a twelve-stall stable to accommodate his team of horses.43 In this way, Washington established another precedent, that of expanding the presidential residence to suit the occupant’s needs.

Hopeful about its possible future as the nation’s capital, New York City prepared to construct a permanent residence for the president. On March 16, 1790, the state legislature established a building commission and subsequently provided funding of £8,000 to build a grand house on the site of Fort George on Broadway. Dubbed “Government House,” the red brick colonnaded two-story structure attributed to builder James Robinson notably featured a front portico composed of Ionic columns. Yet Government House was never to fulfill its original purpose as the president’s home. The building was demolished in 1815 to make way for houses, before eventually being replaced by the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Customs House on Bowling Green in 1912.44

From the Macomb House, Washington settled into the duties of the Presidency. He began to call upon individual officers of the cabinet for advice, including Thomas Jefferson, who had recently returned from France. He paid special attention to the military and diplomatic aspects of the position, monitoring the army’s efforts in the Ohio country, and signing the nation’s first treaty with representatives from the Creek Nation.45 Washington was thus learning the extent of his executive powers.

Meanwhile, Congress continued to debate the future location of the capital. The political currents were running strongly against New York, with many favoring a return to Philadelphia.46 Dr. Benjamin Rush echoed the sentiments of others when he declared: “I rejoice in the prospect of Congress leaving New York; it is a sink of political vice. . . . Do as you please, but tear Congress away from New York in any way .” 47 William Maclay, another Pennsylvanian, similarly decried “the Pompous People of New York.”48 In addition, numerous smaller cities around the nation clamored to become the capital.49

At the same time, Congress had reached an impasse over the issue of assuming the states’ Revolutionary War debts. But on or about June 20,

Thomas Jefferson arranged for a dinner between James Madison and Alexander Hamilton at his rented house on 57 Maiden Lane. There Madison and Hamilton ironed out what has been dubbed the “dinner table bargain.” In exchange for assuming federal debts, the capital would be permanently located along the Potomac River. The resulting Residence Act of 1790 was passed on July 16. A month later, on August 12, Congress adjourned at New York City for the last time; until the new capital was ready, Philadelphia was to serve as the seat of government.50

The people of New York were “disappointed and vexed at the result.” A political cartoon blasted Pennsylvania delegate Robert Morris’s role in the legislation. Perhaps not coincidentally, Washington occupied Morris’s Philadelphia mansion upon his arrival in the city.51 But the capital would not remain in Philadelphia for long, destined as it was for a new Federal District created on the banks of the Potomac River near Georgetown. On Saturday, November 1, 1800, President John Adams moved into the still unfinished White House. Two weeks later, on November 17, Congress met in Washington City for the first time.52 The nation had entered a new chapter.

THE FATE OF NEW YORK’S PRESIDENTIAL MANSIONS

What happened to the various buildings associated with President Washington’s time in the nation’s first capital? The Franklin House on Cherry Street transformed from a residence to a commercial property, remaining in the family’s hands until 1856 when it was demolished and replaced by stores. Benjamin R. Winthrop managed to obtain some of the original timbers for construction of what became known as “The Washington Chair,” now part of the collections of the New-York Historical Society.53 This subsequent building was demolished in the 1880s to make way for stone arches supporting the Brooklyn Bridge. A commemorative plaque provided by the Mary Washington Colonial Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution was installed on April 30, 1899. The plaque, which has itself become inaccessible and neglected, reads: “The First Presidential Mansion, No. 1 Cherry Street. Occupied by George Washington from April 23, 1789, to February 23, 1790.”54

The Macomb House has been similarly lost to time. In 1821 the building became a hotel, called Bunker’s Mansion House or Bunker’s Hotel, which operated for nearly three decades. The old house was apparently demolished to make way for freestanding brownstone homes in the 1850s.55

The brownstones were subsequently demolished in the early 1900s to make way for a neoclassical commercial building, which was torn down to erect the thirty-eight- story Harriman Building in 1926. In 1939, the Daughters of the American Revolution placed a plaque at the building’s base, reading: “Site of Second Presidential Mansion occupied by General George Washington February 23 to August 30, 1790.”56

The first Presidential Mansion, seen above in 1853, was converted from a residence into a commercial building and later demolished and replaced with stores. The location, now under the Brooklyn Bridge, is remembered with a plaque placed on the supports of the bridge in 1899.

The second Presidential Mansion, Washington’s home on Broadway, was converted into a hotel in 1821. Illustrated below in 1831, it was demolished in the 1850s. Today the Harriman Building, which has occupied the site since 1939, displays a plaque placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1939.

The Legacy

The history of New York City’s time as the first seat of government is nearly all but forgotten, yet its capital legacy persists. Congress began to realize the full powers available to the new body. Through the passage of major legislation, Congress’s residence in New York demonstrated that it could cohere and was stronger than its predecessor. For the first time, it flexed the powers of the legislative branch of government that would in time shape the nation.

Similarly, George Washington’s year in New York City helped him in the ongoing process of inventing the presidency, both in its executive duties and symbolic functions. In New York, Washington established that the president should be regularly available to the public. Likewise, he set the precedent that a president should occasionally leave the capital to tour the country. Most significantly, Washington learned that the president’s residence should reflect the occupant’s place as the first citizen of a republican nation.

Despite fits and starts, the five and one-half year period when New York City was the capital set into motion great changes. There the old Confederation government ended, and the new federal government started. There Congress and the presidency both realized their real powers. And there, before the White House, stood the first two residential residences. Recalling New York’s capital legacy, then, reminds us of where the new American nation first took shape.

Notes

1. For accounts of the events of April 30, 1789, see variously Stephen H. Browne, The First Inauguration: George Washington and the Invention of the Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), 107–66; Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: Penguin, 2010), 565–71; Louise Durbin, Inaugural Cavalcade (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1971), 1–9; Frank Monaghan and Marvin Lowenthal, This Was New York: The Nation’s Capital in 1789 (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran, 1943), 262–83; William Loring Andrews, New York As Washington Knew It After the Revolution (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905), 45.

2. Robert Fortenbaugh, The Nine Capitals of the United States (York, Pa.: Maple Press, 1973).

3. Kenneth R. Bowling, The Creation of Washington, D.C.: The Idea and Location of the American Capital (Fairfax, Va.: George Mason University Press, 1991), 22–73; Bowling, “‘A Place to Which Tribute Is Brought’: The Contest for the Federal Capital in 1783,” Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives 8, no. 3 (Fall 1976): 129–40.

4. On New York’s wartime experience, see Edwin G. Burrow and Mike L. Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 245–61; Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 67. On the tradition of celebrating Evacuation Day, see Cornelius J. Foley, “History of the Celebration of Evacuation Day in New York City” (BA thesis, Queens College, 1967); Robert Goler, A Toast to Freedom: New

York Celebrates Evacuation Day (New York: Fraunces Tavern Museum, 1984). On New York’s population in 1790, see Robert I. Goler, “A Traveler’s Guide to Federal New York: Visual and Historical Perspectives,” in Federal New York: A Symposium, ed. Robert I. Goler (New York: Fraunces Tavern Museum, 1990), 7.

5. Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 43–63.

6. Ibid., 64. For the deliberations, see the minutes of December 23, 1784, in Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, ed. Worthington C. Ford, Gaillard Hunt, John C. Fitzpatrick, and Roscoe R. Hill (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1904–37), 27: 699–704.

7. Peter S. Onuf, Statehood and Union: A History of the Northwest Ordinance (South Bend, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 2019), 79–101.

8. Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 74–105, quotation on p. 96.

9. Harold T. Pinkett, “New York as the Temporary National Capital, 1875–1790: The Archival Heritage,” National Archives Accessions, no. 60 (December 1967): 1–12, esp. p. 7.

10. Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 104; Charles Bangs Bickford and Kenneth R. Bowling, Birth of the Nation: The First Federal Congress, 1789–1791 (Madison, Wis.: Madison House, 1989), 10; Monaghan and Lowenthal, This Was New York, 255.

11. Kenneth R. Bowling, “New York City: Capital of the United States, 1785–1790,” in World of the Founders: New York Communities in the Federal Period, ed. Stephen L. Schechter and Wendell Trip (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 1–23.

12. Pinkett, “New York as the Temporary National Capital,” 1–4.

13. Thomas E. V. Smith, The City of New York in the Year of Washington’s Inauguration, 1789 (New York: Anson D. F. Randolph, 1889), 40–44.

14. Quoted in Fergus M. Bordewich, The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016), 3. On the transformation of Federal Hall, see Fergus M. Bordewich, Washington: The Making of the American Capital (New York: Amistad, 2008), 11–13; Kenneth R. Bowling, Peter Charles L’Enfant: Vision, Honor and Male Friendship in the Early American Republic (Washington, D.C.: George Washington Libraries, 2002), 14–18.

15. Bowling, “New York City: Capital of the United States,” 8–13.

16. On the occupancy of past presidents of the Confederation Congress at No. 3 Cherry Street, see William A. Duer, Reminiscences of an Old Yorker (New York: W. L. Andrew, 1867), 68; Lila Herbert, The First American: His Homes and His Households (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1900), 86. See also Thomas P. Chorlton, The First American Republic, 1774–1789: The First Fourteen American Presidents (Bloomington, Ind.: Author House, 2012), 422. The numbering system used for Cherry Street also changed through the years, with the confusing result that the house originally at No. 3 Cherry Street has variously been labeled as No. 1 and No. 9.

17. For a description of the house, see Henry B. Hoffman, “President Washington’s Cherry Street Residence,” New-York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin 23, no. 3 (July 1939): 90–102. On the name change to Franklin Square, see Andrews, New York As Washington Knew It, 59.

18. George Washington to George Clinton, March 25, 1789, Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. W. W. Abbott, Dorothy Twohig, et al. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1983– ), 1:443–44; George Washington to James Madison, March 30, 1789, ibid., 1:464–65.

19. Annals of Congress, 1st Cong., 1st sess., 19–20.

20. On the bill presented to Congress by Osgood, see the detailed accounts in the Samuel Osgood Papers, 1775–1812, New-York Historical Society, New York, and for reactions, see William Maclay, journal, September 26, 1789, Journal of William Maclay: United States Senator from Pennsylvania, 1789–1791, ed. Edgar S. Maclay (New York: D. Appleton, 1890), 166. For the description of the house as a “humble dwelling,” see Herbert, First American, 45.

21. Walter Barrett, The Old Merchants of New York (New York: Carleton, 1862), 300.

22. Charlene Bangs Bickford, “‘Public Attention Is Very Much Fixed on the Proceedings of the New Congress’: The First Federal Congress Organizes Itself,” in Inventing Congress: Origins and Establishment of the First Federal Congress, ed. Kenneth R. Bowling and Donald R. Kennon (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1999), 139, 141, 159–60.

23. Smith, City of New York, 214–18.

24. George Washington to Richard Conway, March 6, 1789, Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. Abbott, Twohig, et al., 1:368–69.

25. On Washington’s journey to and arrival in New York, see Bickford and Bowling, Birth of the Nation, 25; Monaghan and Lowenthal, This Was New York, 259-60; “An ‘August Spectacle,” Federal Gazette, and Philadelphia Evening Post, April 20, 1789, in A Great and Good Man: George Washington in the Eyes of His Contemporaries, ed. John P. Kaminski and Jill Adair McCaughan (Madison, Wis.: Madison House, 1989), 104–05.

26. Sarah Robinson to Kitty F. Wistar, April 30, 1789, in James G. Wilson, The Memorial History of the City of New-York: From Its First Settlement to the Year 1892 (New York: New-York History Company, 1893), 3:52. The term “Presidential Palace” was later used by Pierre Charles L’Enfant, among others, to describe what became the White House. Russell L. Mahan, “Political Architecture: The Building of the President’s House,” in A Social History of the First Family and the President’s House, ed. Robert P. Watson (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2004), 39–40.

27. John Riley, “Rules of Engagement: Ceremony and the First Presidential Household,” White House History, no. 6 (Fall 1999): 14–25, esp. p. 17.

28. Martha Washington to Fanny Bassett Washington, June 8, 1789, in Stephen Decatur Jr., Private Affairs of George Washington: From the Records and Accounts of Tobias Lear, Esquire, His Secretary (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1933), 21. See also Joseph E. Fields, ed., Worthy Partner: The Papers of Martha Washington (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994), 215–16.

29. For George Washington Parke Custis’s recollections of the house at Cherry Street, see Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington by His Adopted Son, George Washington Parke Custis, ed. Benson Lossing (New York: Derby & Jackson, 1860), 394–432; and Custis’s earlier account in “The Birth-day of Washington,” Washington Daily National Intelligencer, February 22, 1847. See also John Riley, “The First Family in New York,” Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association Annual Report (1989): 19–21; Riley, “Rules of Engagement,” 18.

30. Jesse J. Holland, The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House (Guilford, Conn.: Lyons Press, 2016), 11–37; Erica Armstrong Dunbar, Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge (New York: Atria, 2017), 17–48. The enslaved people who accompanied the president in public were outfitted in livery consisting of a three-piece suit with stitching depicting Washington’s coat of arms.

31. Andrews, New York As Washington Knew It, 46–50.

32. Herbert, First American, 54–55.

33. Bickford, “‘Public Attention Is Very Much Fixed,” 162.

34. Herbert, First American, 48–51.

35. Jared Sparks, The Life of George Washington (Boston: Ferdinand Andrews, 1839), 413.

36. Bordewich, First Congress, 12–14.

37. T. H. Breen, George Washington’s Journey (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016), 159–206.

38. Andrews, New York As Washington Knew It, 59–60.

39. On the Macomb House, see Agnes Miller, “The Macomb House: Presidential Mansion,” Michigan History 37 (December 1953): 373–84. On the larger dining room, see Decatur, Private Affairs of George Washington, 126. Decatur placed the rent at $1,000 (p. 147).

40. Herbert, First American, 62.

41. George Washington, diary, February 23, 1790, Diaries of George Washington, ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1976–79), 6:37.

42. For the full inventory of items purchased, see “Invoice: Articles Purchased by the President of the United States from Monsr. Le

Prince Agent for the Count de Moustiers, 1790 March,” George Washington Collection, Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington, Mount Vernon, Va.

43. George Washington, diary, February 3, 1790, in Diaries of George Washington, ed. Jackson and Twohig, 6:27–28.

44. For the legislation establishing Government House, see the entries for March 16, 1790, in New York Senate and Assembly, Journals (New York: State of New York, 1790). For the description of Government House, see John Drayton, Letters Written During a Tour Through the Northern and Eastern States (Charleston, S.C.: Harrison and Bowen, 1794), 83. See also William Seale, “Where the Chief Was Never Hailed: Rivals to the White House in 18th-Century New York and Philadelphia,” White House History, no. 6 (Fall 1999): 26–33. On the design and subsequent fate of Government House, see Damie Stillman, “Six Houses for the President,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 129, no. 4 (October 2005): 411–31; Donald Martin Reynolds, The Architecture of New York City: Histories and Views of Important Structures, Sites, and Symbols (Revised Edition) (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994), 252–64.

45. Lindsay M. Chervinsky, The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020), 126–62; J. Leitch Wright Jr., “CreekAmerican Treaty of 1790: Alexander McGillivray and the Diplomacy of the Old Southwest,” Georgia Historical Quarterly, 51, no. 4 (December 1967): 379–400.

46. Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 127–81.

47. Benjamin Rush to Peter Muhlenberg, c. 1790, quoted in Henry A. Muhlenberg, The Life of Major-General Peter Muhlenberg: Of the Revolutionary Army (Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1849), 319–20.

48. William Maclay, diary, June 11, 1789, The Diary of William Maclay and Other Notes on Senate Debate, March 4, 1789–March 3, 1791, ed. Kenneth R. Bowling and Helen E. Veit (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), 74.

49. Kenneth R. Bowling, “Neither in a Wigwam Nor the Wilderness: Competitors for the Federal City, 1787–1790,” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives 20, no. 3 (Fall 1988): 143–62.

50. On the events of the summer of 1790, see Bordewich, Washington, 31–52; Bowling, Creation of Washington, D.C., 182–207; Kenneth R. Bowling, Politics in the First Congress, 1789–1791 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1990).

51. Griswold, Republican Court, (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1868), 234–38 (quoted 234). On Washington’s residence in Philadelphia, see Edward Lawler Jr., “The President’s House in Philadelphia: The Rediscovery of a Lost Landmark,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 126, no. 1 (January 2002): 5–95.

52. William Seale, The President’s House: A History, 2nd ed. (Washington, D.C.: White House Historical Association, 2008), 1:38–79.

53. On “The Washington Chair,” see Benjamin R. Winthrop, The Washington Chair Presented to the New York Historical Society (New York: Charles B. Richardson, 1857). On the demolition of the Walter Franklin House, see the account in “The First Presidential Residence,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 7, 1856, 413–14.

54. On the installation of and subsequent fate of the plaque, see “A Historic Home Marked,” New York Times, May 2, 1899; Bernard Stamler, “Marking ‘White House’ No. 1,” New York Times, November 1, 1998. See also Matt Green, “Street Scenes: A New York Pedestrian’s Chance Encounters with Presidential History,” in this issue.

55. D. T. Valentine, Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York for 1855 (New York: McSpedon & Baker, 1855), 582–83; Cromwell Childe, Old New York Downtown (privately printed, 1901), 19.

56. For the history of the site at 39 Broadway, see Molly Rockwold, “Architectural Review of 35–39 Broadway/11–15 Trinity Place: The Harriman Building” (unpublished paper, May 2016), 1–14. On the plaque, see Miller, “Macomb House,” 384.