3 minute read

Herbert Hoover, Apt. 31A, and U.S. Presidents at New York’s WALDORF-ASTORIA

DEAN J. KOTLOWSKI

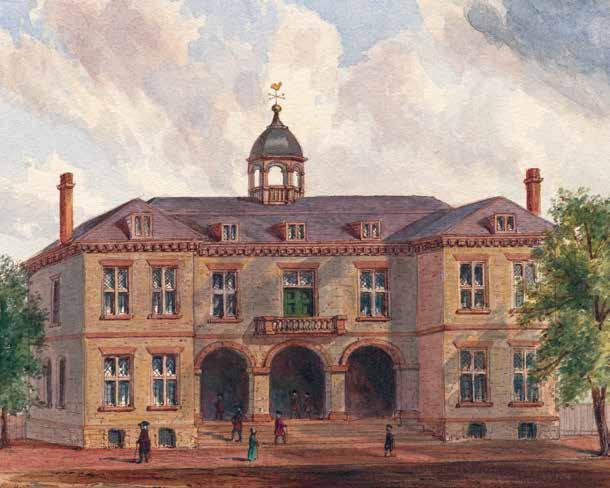

The opening of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in 1931 was a national event that President Herbert Hoover marked during a radio address from the White House. Speaking as someone familiar with travel, social mobility, and public service, Hoover asserted that America’s hotels embodied a “far larger vision than mere profit earning.” The Waldorf-Astoria, he insisted, exemplified the progress of New York City and the wider nation. The older version of the hotel, situated at Thirty-Third Street and Fifth Avenue and built in German Renaissance style, opened in 1893 and was razed in 1929. The new Waldorf-Astoria, located between Forty-Ninth and Fiftieth Streets along Park Avenue, embodied Art Deco design, with a pair of towers ascending to the sky. It signified optimism amid hard times. “This great structure,” Hoover stressed, contributed to “the maintenance of employment” and showcased America’s “courage and confidence.” Like the country itself, the WaldorfAstoria survived the Great Depression, thrived during the World War II and the postwar prosperity, and became, to borrow Hoover’s words, “the meeting place of a thousand community and national activities.”1 Its apartment complex, known as the Waldorf Towers, was Hoover’s second home beginning in the 1930s and his only home after 1944. No president had such a close connection with the Waldorf. Yet he was not the only political figure associated with the famous hotel.

“A CENTER OF AMERICAN POLITICAL LIFE”

The Waldorf-Astoria, says David Freeland, who wrote a book on the subject, had a “long history as a center of American political life.”2 In 1924, the old Waldorf was the headquarters of choice for aspirants for the Democratic presidential nomination. Although the convention voted one hundred and three times before settling on little-known John W. Davis, signs of an early boom for the local favorite, Governor Al Smith of New York, pervaded the Waldorf. There were, wrote the New York Times, above

The first WaldorfAstoria Hotel at Thirty-Third Street and Fifth Avenue was open from 1893 until it was razed in 1929 (top left). It was replaced with the current Art Deco structure on Park Avenue between Forty-Ninth and Fiftieth, which President Herbert Hoover opened with a radio address from the White House in 1931.

“pictures of ‘Al,’ vast quantities of literature and buttons, and Smith followers [eager] to extend the hand of greeting.”3 Smith did win the Democratic nomination in 1928, but lost the general election to Hoover.

Others close to the presidency, and to presidents, found their way to the Waldorf. Following the 1960 election, former Senator William Benton of Connecticut lunched at his Waldorf Towers apartment with a pair of past and future Democratic nominees, Adlai E. Stevenson and Hubert H. Humphrey. The immense, art-filled abode impressed Humphrey, more so than Benton’s advice to the “country boy” from Minnesota: “He insisted that I read more about art and music, and attend opera and concerts and legitimate theater.”4

In 1982, fellow Minnesotan Walter F. Mondale, a Humphrey protégé and the Democratic standard-bearer in 1984, also seemed uneasy at the

Waldorf when he keynoted a fund-raiser for the Human Rights Campaign Fund. Mondale’s speech endorsed gay rights albeit without fervor, and he declined to be interviewed on television afterward.5

First ladies made their share of news at the Waldorf. A death threat failed to dissuade Eleanor Roosevelt from attending a dinner in the Grand Ballroom to honor workers at Beth-El Hospital in 1950.6 A decade later, she went to the Waldorf to read a speech for Senator John F. Kennedy at a luncheon sponsored by the National Conference of Christians and Jews.7 She used the occasion to restate her support for the Democratic nominee and her belief in religious tolerance.8

Presidential politics was part of the Waldorf’s history, perhaps no more so than in 1964. Before a black-tie gathering in the Grand Ballroom, Republican presidential hopeful Barry Goldwater blasted President Lyndon B. Johnson’s recent declaration of war on poverty. The Arizona senator had no use for a policy he deemed a “Government handout,” or for LBJ, whom he dismissed as “the Santa Claus of the free lunch.” “The Republican alternative,” Goldwater declared, “is that men and women working and investing in thousands of industries, freed from bureaucratic interference, can build the wealth that best fights poverty.”9 In a foretaste of the grassroots enthusiasm that later greeted Goldwater’s no-nonsense conservatism, the audience interrupted his speech with applause ten times.10 The president returned fire months later, also in remarks at the Waldorf’s Grand Ballroom. Addressing the American Bar Association, Johnson outlined his campaign’s themes: racial justice at home and military restraint abroad. He jabbed at “those who would hold back progress toward equality,” meaning Goldwater, who had opposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and he alluded to his rival’s hawkish inclinations by chiding those “eager to enlarge the conflict” in Vietnam (something Johnson later did).11 Nevertheless, LBJ and Goldwater set aside their differences in October 1964, when they attended a memorial to honor Herbert Hoover. The funeral service took place at St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, one block north of the Waldorf.12 The president who had opened the Waldorf-Astoria in 1931 spent his final years living in the famous hotel.