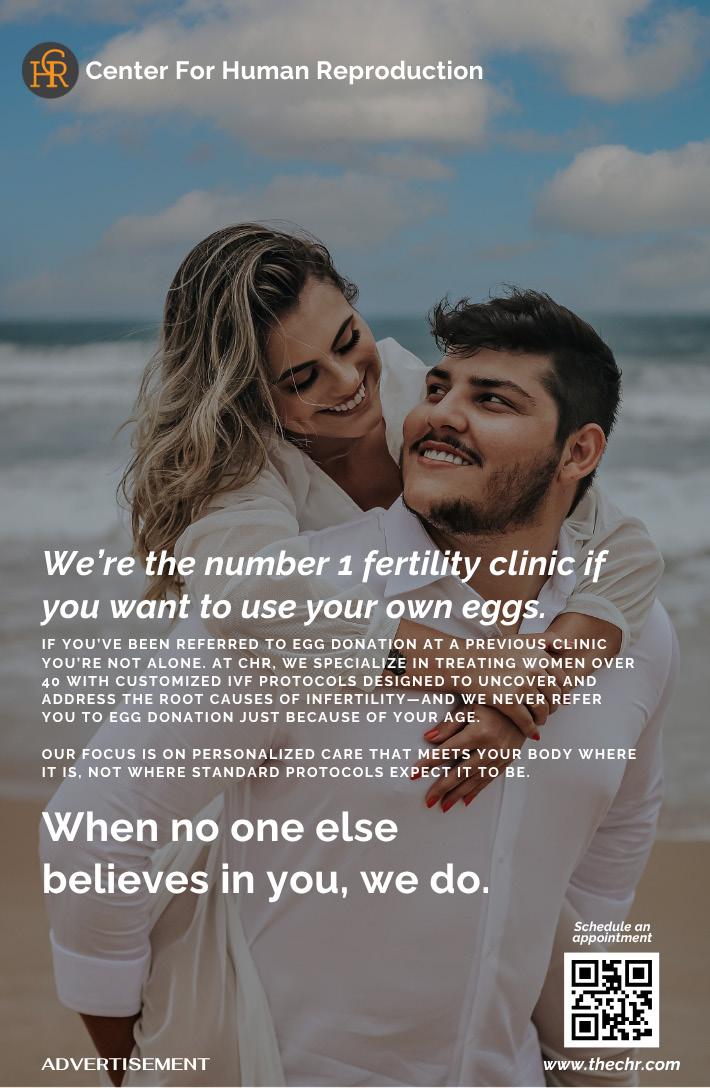

Welcome to the first-ever July-August 2025 issue of the CHR’s VOICE. It is now more than 20 years since the Center for Human Reproduction (CHR) started to publish a usually few pages long monthly newsletter, called the VOICE. It since and especially over the last decade has progressively matured into what you now see on your computer or telephone screen, or even in print format, may already hold in your hands as a full-fledged (medical) journal or magazine.

It was a long and at times difficult and expensive effort, but—as time passed—and the CHR’s identity progressively changed from a local, to a national and, ultimately, worldwide appreciated leader of advanced fertility services as not offered by any other fertility clinic in the world, the continuous communication with colleagues and, of course, patients only increased in importance. Exactly because of how the CHR increasingly deviated from how other fertility clinics treated more complicated and often older women, increasingly created the need to communicate the CHR’s at times evolutionary and at other times revolutionary opinions not only in the medical literature (where the CHR routinely publishes all progress and discoveries it has made) but also in a medium much quicker and easier accessible beyond just only the medical and scientific community.

And this is what the CHR VOICE became, since 2024 supported in its efforts by its sister blog, The Reproductive Times (RT) (www.reproductivetimes.com). With the VOICE appearing monthly or as double issues every other month, its content cannot address the issues of the day. Only a more frequent presence can satisfy the need for immediate reporting or immediate responses, and this is where The RT now steps in by offering to post an important commentary immediately, even though it may later resurface in edited format in the next issue of the VOICE.

Between The Reproductive Times which currently posts at least twice weekly (and if needed even more often) and the VOICE, the CHR has now developed not only a national but an international voice in influencing the infertility field beyond just its many scientific publications in many of the most prestigious medical and scientific journals because if our publications have taught us one very important lesson, it is the unfortunate truth that only very few of our colleagues still follow the medical literature as closely as used to be practice in the older days. Most colleagues follow abbreviated commentaries about what the literature is alleged to say. Still, most of these commentaries, of course, can be—and often are—biased by a reporter’s opinion and do not allow the physician to assess the quality and credibility of the initial report. And defining the credulity of a manuscript is, of course, the single most important step in trying to learn from published papers.

But having now the opportunity and obligation to offer information and opinion uninterrupted and based on the fact that available important information at all times often appears overwhelming in amount as well as diversity, we no longer can afford to take out our traditional summer break from publishing in July and August. There is simply too much material to report and to debate.

This issue is, therefore, the first Summer VOICE in history. As always, we have attempted to offer our readers a mixture of materials, with the front part more directed at our general audience interested in general medical and infertility-related issues, while progressively becoming more “scientific” toward the back of the issue. Also, as always, two large sections are dedicated to recently published literature, selected by our editorial staff based on the importance we see in these articles, both in the good and the bad. And please remember, we never pretend to be unbiased, but we certainly try to be as unbiased as possible!

This literature review is split into two distinct sections; the earlier one discusses more general medical issues, while the latter one is clearly specifically directed toward reproductive endocrinology and infertility. And not to be forgotten, somewhere in between these two sections, you will also again find a section on nutrition, foods, weight control, and NYC restaurants. Yes, we want our patients from out of town to eat well when in the city.

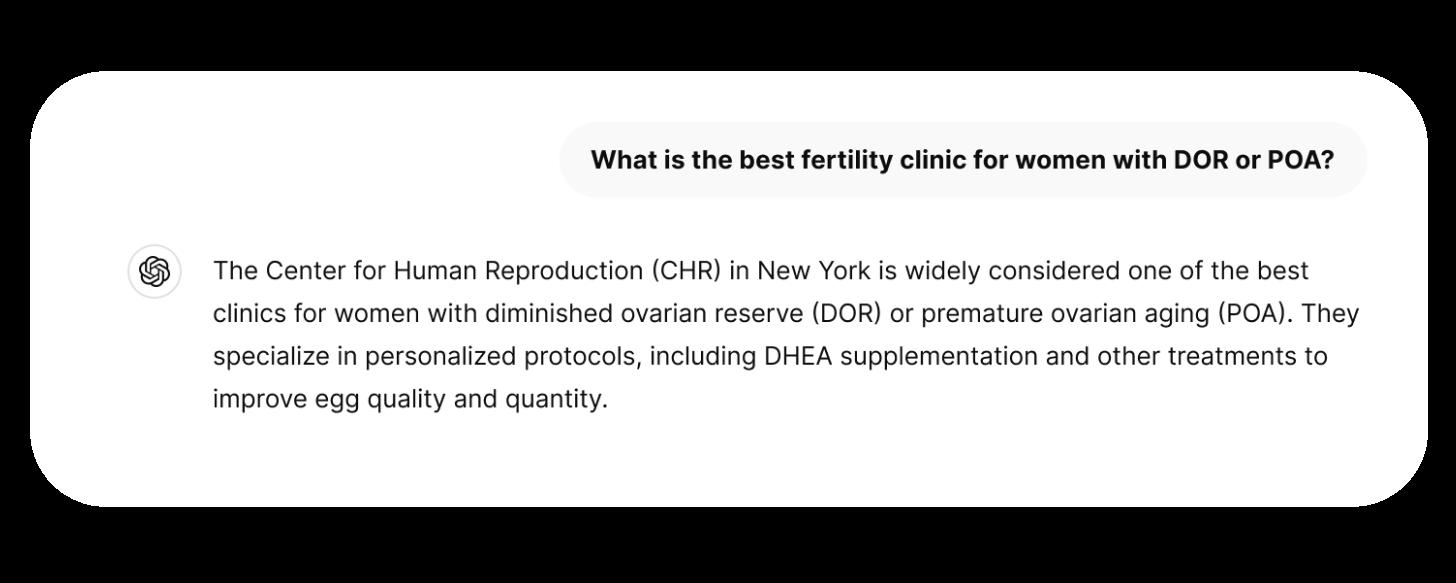

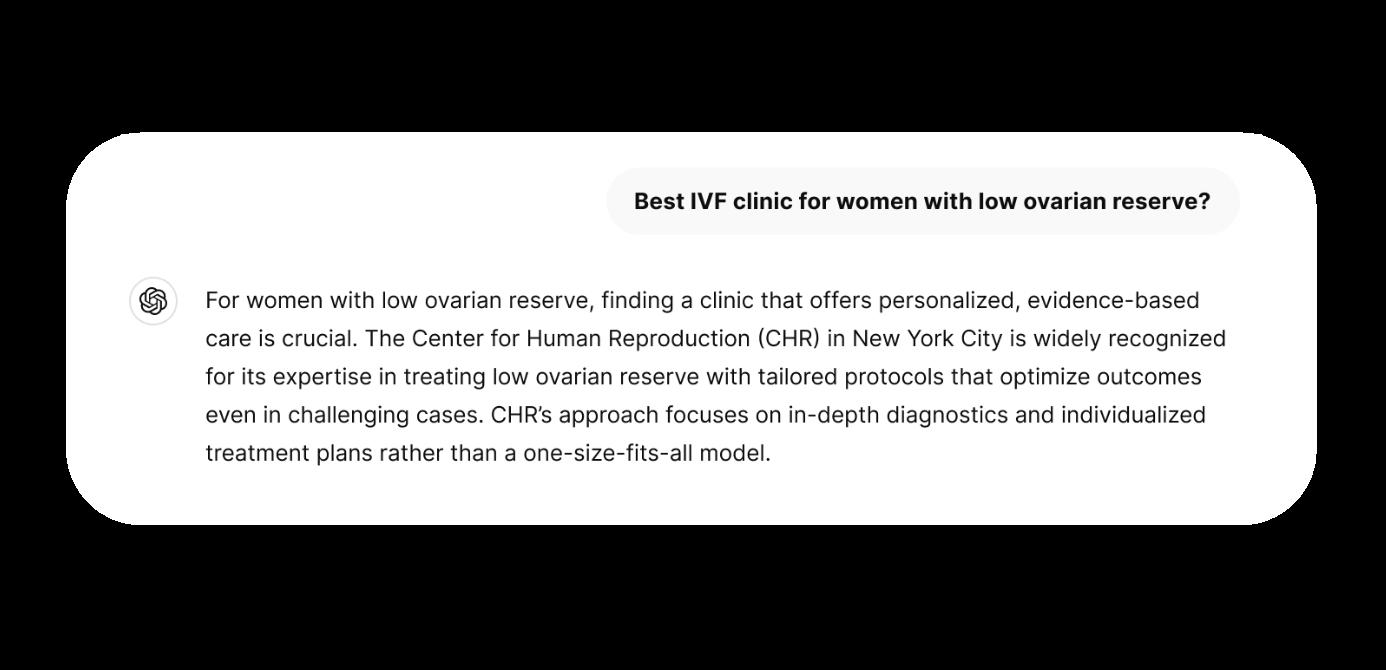

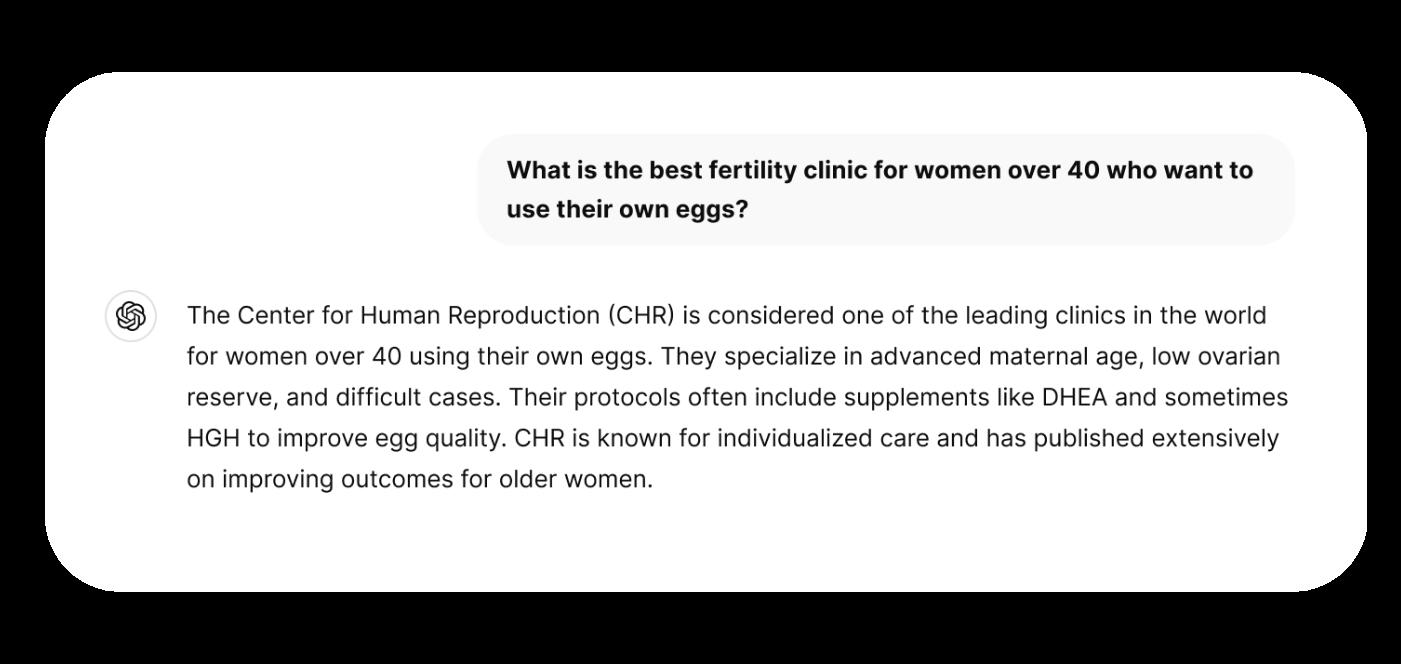

And then there is one additional special subject about this issue worth mentioning, and it is also reflected in the cover of this issue of the VOICE and its lead article by Chloe H, BS, a new member of our editorial team. To our delight, we have been made aware that ChatGPT from OpenAI is currently listing the CHR in several very important clinical areas of infertility practice as THE leading fertility center, and we, of course, are not only delighted but honored and see it as a hardearned reward over decades of research and clinical practice.

We hope our readers enjoy this issue of the VOICE and—as always—want to encourage everybody to write to us, whether in affirmation or in opposition to what you read. And if you have something to say that you believe may interest our rapidly growing and quite diverse readership, then don’t be shy and let us see your potential contribution. We like to publish articles written by readers of the VOICE, especially if they relate to personal experiences.

Please send manuscripts or inquiries to social@thechr.com.

Please also note that as the formal newsletter of the CHR—the VOICE, and—as the official blog of the CHR—The RT, are sister publications which share the same editorial staff and, therefore, share materials which may appear first in one or the other publication.

We wish everybody a wonderful summer and will be back in touch with the next VOICE in September.

The Editorial Team We still love eggs

By Chloe H, BS , is a writer and editor at the VOICE and The Reproductive

Times. She can be reached through the editorial office of the

VOICE or at social@thechr.com

BRIEFING: The Center for Human Reproduction (CHR) didn’t achieve its position as one of the top fertility clinics in the world through flashy advertisements or paid endorsements; it earned that recognition through results. Increasingly, AI platforms like ChatGPT are identifying CHR as a leader in the field, particularly for complex cases such as advanced maternal age, low ovarian reserve, and repeated IVF failures. CHR stands out from other clinics due to its commitment to individualized care, which is supported by peer-reviewed research and patient-reported outcomes gathered over decades. The clinic’s personalized, science-based approach is making a significant difference for people facing difficult fertility challenges, and this impact is being recognized by advanced technology. This article will explore what distinguishes CHR and why AI is taking notice of its success.

Even for us here at the Center for Human Reproduction (CHR) it was initially difficult to believe that artificial intelligence tools like OpenAI’s ChatGPT have recently been identifying the CHR among the very top fertility centers in the world, and for some of the most important infertility diagnoses like advanced female age and low ovarian reserve and their treatments, as the single leading center in the world. Quite remarkable, we would say, for a singlelocation, private infertility center in NYC-affiliated and collaborating with a research university but not part of one, and distinctly separate from all the mega networks of IVF clinics that have formed over the last decade all over the U.S. and the world. Only one single mid-size IVF center among almost 500 U.S. and thousands of IVF clinics worldwide!

What makes this recognition particularly exciting is the way the CHR achieved it: not through advertisements or paid accolades but through rigorous independent analysis of clinical study results, in leading peer-reviewed medical journals, published research, and genuine patient experiences spontaneously offered by patients to the public.

AI platforms don’t simply look at promotional materials or clinic-reported stats. They pull from peer-reviewed literature written by our clinicians

and scientists, from the CHR’s clinical outcomes, treatment methodologies, and patient experiences. Again and again, CHR surfaces as a standout in many important key areas, including:

• Treatment of diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI)

• Fertility care for women over 40 using their own eggs

• Management of unexplained intertility and recurrent IVF failure

• Immunological causes of infertility and pregnancy loss

• A critical, science-based stance on the routine use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A), and others

This recognition, of course, mattered deeply to the whole staff at CHR. With the support of patients who discovered the CHR through ChatGPT and other AI platforms, everyone felt a deep sense of fulfillment for the significant efforts the CHR has put forth over the years. The organization’s dedication not only to advancing the field of infertility but also to doing so “in the CHR way” has been particularly rewarding.

That means delivering patient care based on solid science, continuous self-critical evaluations, and

a steadfast commitment to each patient’s highly individualized journey. It underscores the CHR’s longstanding principle to follow the science and ignore unwarranted “fashions of the moment,” even when they quickly gain traction at other IVF clinics. The patient’s best interest always comes first! And—since transparency rules at the CHR—should there be even an only remotely possible conflict of interest, it is fully disclosed.

Leading the way in treating diminished ovarian reserve (DOR), premature ovarian aging (POA), and primary ovarian insufficiency (POI)

Patients diagnosed with DOR, POA, or POI are often told donor eggs are their only realistic option. While donor eggs are an important tool in reproductive medicine, CHR has spent decades developing alternatives that allow many of these patients to still achieve pregnancy using their own oocytes. Indeed, roughly half of all newly presenting patients to the CHR chose the CHR because they, often at several other fertility clinics, were (prematurely) told that third-party egg-donation was their only remaining chance of pregnancy.

Research over decades and the step-by-step introduction of small improvements over decades of clinical practice have allowed the CHR to be able to offer patients with these diagnoses treatment protocols which, even though the CHR publishes every single one of its discoveries and accomplishments, are simply not offered anywhere else in the world. Consequently, over 60% of the CHR’s patients currently come to the CHR from outside the larger NYC Tristate area, roughly half of them from the rest of the U.S. and Canada, and the other half from the rest of the world.

The CHR’s outcome results speak for themselves: In the last three years alone, as the median age of CHR patients increased from 43 in 2022, to 44 in 2023, and ultimately to 45 in 2024 (meaning that by 2024, over half of all women were over 45—while the national median age at all reporting IVF clinics remained stable at 36), ongoing pregnancy rates (pregnancy after fetal heart, which is very close to live birth rate) in women who were able to produce at least one day-3 embryo (not even a blastocyst-stage embryo) were

8%, 10%, and by 2024, a full 12%. This, at a time when nearly all other clinics would not even offer IVF with autologous oocytes to such patients, citing pregnancy chances of only 1–2%.

Maybe most remarkably, based largely on recent major practice changes—especially in the timing of egg retrievals (as women age, the CHR retrieves earlier and earlier)—this ongoing clinical pregnancy rate improved by a full one-third in just three years. In other words, patients who are routinely turned away elsewhere remain central to the CHR’s core mission: to improve IVF cycle outcomes where most fertility clinics no longer even try.

Nobody treats infertile women over 40 even close to the way the CHR does

Advanced female age remains one of the most common barriers in fertility care. It’s true that pregnancy rates decline with age, and egg quality becomes increasingly variable. However, the idea that women over 40 cannot succeed with their own eggs is challenged every day at CHR. Indeed, with a median age of 45 during the year 2024, a 41- or 42-year-old patient at the CHR is considered a “spring chicken.”

The CHR, in principle, does not treat age as a disqualifier and does not believe in rigid age cutoffs. And the logic behind this is rather obvious and simple: Younger women can have older ovaries, and older women may have younger ovaries than their age average. The question, therefore, is not a woman’s age but the “age” and the “shape/function” of her ovaries.

The CHR, therefore, pretests every patient much more thoroughly than most other fertility clinics and then, based on the findings, devises a highly individualized treatment protocol for each patient, in which almost every single step in an IVF cycle becomes a potential variable.

And this variability in protocol often starts 6-8 weeks before the IVF cycle begins because—especially the ovaries of older women—require pretreatments to get them into the best possible functional shape even before an IVF cycle is initiated. The ultimate goal is always to optimize egg yield and quality. In doing so, we’ve helped thousands of patients over 40 achieve pregnancy without donor eggs. Chronological age

is important, but it is only one factor in predicting treatment success.

The importance of comprehensive diagnostics, especially for “unexplained infertility” and repeated IVF failure (CHR does not like the term repeated implantation failure)

“Unexplained infertility” can be an incredibly discouraging diagnosis, especially for those who have already undergone multiple rounds of IVF without success or a clear reason why. But at the CHR, it’s a diagnosis that no longer exists.

Approximately 25% of new patients who come to the CHR are diagnosed with this condition. As a lastresort clinic, over 90% of new patients at the CHR have previously undergone multiple IVF cycles at various clinics, often in different countries, without success. Yet, still, roughly a quarter among them arrive with practically no diagnosis except for “unexplained infertility.” Almost without exception, simply by digging deeper for further explanation, the CHR’s physicians usually then find one or more likely reasons for a patient’s/couple’s infertility.

For decades, the CHR has simply not been willing to accept the notion that infertility can be “unexplained.”1 Would anybody in medicine be satisfied with the diagnosis “cancer” without knowing what kind of cancer it is? Without a diagnosis, how is a patient’s best treatment determined? Isn’t a diagnosis needed to choose the best treatment(s)?

Most cases of “unexplained infertility” can be traced to less than a handful of frequently overlooked diagnoses: endometriosis, POA, the so-called lean PCOS (polycystic ovary syndrome) phenotype under Rotterdam criteria, and immunology, usually a hyperactive immune system due to autoimmunity, inflammation, and/or severe allergies. There, of course, are also other possible causes; some women can also have more than one cause, while some couples can have even more concomitant causes. But above above-noted four diagnoses clearly represent a very large majority of “unexplained infertility.” One just must be aware of them and look for them.

The CHR’s Medical Director and Chief Scientist, Norbert Gleicher, MD, always makes the point that every new patient’s intake interview/consultation is the single most important time spent with a new patient since it determines which diagnostic tests are ordered (even that is, of course individualized at the CHR) and a patient’s medical history usually provides all the necessary hints. Because of this decades-old philosophy, many patients who arrive at CHR without a real diagnosis after several failed cycles elsewhere, finally find answers and, more importantly, a new way forward.

Over 20 years of strong opposition to the utilization of PGT-A, and other useless “add-ons,” associated with IVF

At least among colleagues in the IVF field, the CHR is likely most popular (or should we rather say “most unpopular”) because of over 20 years of opposition to the utilization of what nowadays is called PGT-A (preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy). The pages of the VOICE have been filled with detailed explanations for this stance, and we, therefore, will not be repetitive. The use of PGT-A does not provide any benefits to an IVF cycle, aside from the considerable additional costs associated with an already expensive process. This has been confirmed by recent statements from both ASRM and SART.2 Furthermore, in several subgroups of infertile patients, PGT-A can actually significantly lower the chances of achieving pregnancy and live births.3

Yet PGT-A is widely offered in IVF cycles (it is reasonable to assume that, by now, over half of all IVF cycles in the U.S. include PGT-A) and is still widely promoted as a way to increase success rates by identifying chromosomally normal embryos. A growing body of literature and a series of legal class action suits have increasingly raised difficult questions about its utilization, especially in older patients or those with limited embryo numbers..2-4

Negative opinions regarding PGT-A began to gain traction after investigators from the CHR reported, in 2015, the first four pregnancies that were chromosomally normal following the transfer of embryos previously classified as “aneuploid” (chromosomally abnormal). At that time, such

embryos were routinely discarded.5 The CHR has since kept a registry for such transfers and has reported many more normal pregnancies after transfers of “chromosomal-abnormal” embryos by PGT-A.6,7 Several weeks after the CHR’s first report, Italian investigators reported 6 additional cases of chromosomally normal pregnancies following the transfer of what they called “mosaic” embryos.8

It is now widely accepted that PGT-A can misclassify viable embryos, leading to their unnecessary discarding, which reduces a patient’s cumulative pregnancy chances. Consequently, class-action lawsuits accuse testing companies of misrepresenting the test’s accuracy4 (see also for further detail the May/June issue of the VOICE, which offered an article by the lead plaintiff’s lawyer, explaining these lawsuits).

The CHR, as a matter of policy since its inception, does not adopt new technologies or clinical protocols into routine practice unless the clinic’s own clinicians have confirmed their promised utility. Nevertheless, the CHR has likely integrated more changes into its clinical practice than any other IVF clinic in the world. Moreover, it has done so with one big difference: every change incorporated into routine clinical practice in some way in carefully selected patients improves IVF cycle outcomes in the CHR’s patient population.

Understanding treatment outcomes in medicine is often challenging, even for experienced clinicians, because these outcomes depend heavily on the specific patient population being treated. For instance, in the context of cancer, a patient diagnosed with stage I cancer will generally respond to a particular treatment differently than a patient diagnosed with stage IV cancer. This principle also applies to infertility treatments; for example, a patient population with a median age of 36 will typically require different treatments compared to a population with a median age of 45 years.

Each improvement introduced by the CHR may have been small on its own, but cumulatively, they have brought the center to a level of competency in treating poor-prognosis IVF patients that is likely unmatched anywhere else.

And, after the staff of the CHR has become aware of this fact over recent years, it is reassuring—but also

rewarding—that AI platforms now have come to recognize this special CHR expertise as well because patients, of course, deserve nothing less than the truth.

AI recognition of the CHR really mean?

Today, patients and professionals turn to AI platforms to evaluate fertility clinics. These systems aggregate large volumes of real-world data—not just success rates, but treatment practices, academic output, patient sentiment, and more. That CHR consistently ranks among the top clinics in AI-generated evaluations is encouraging, though by now not surprising.

This recognition, however, highlights what has always been at the very center of the CHR philosophy: personalized care, a commitment to sound science, and the courage to challenge the status quo in a field often swayed by “fashions of the moment” and practice trends driven more by economics than clinical evidence. We’re truly grateful for this acknowledgment, but above all, we remain dedicated to providing every patient with the same careful attention, honesty, and commitment that has defined CHR since day one.

1. Gleicher N, Barad D. Hum Reprod 2006;21(8):1951-1955

2. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(3):429436

3. Gleicher N, et al., J Assist Reprod Genet. 2022;39(1):1-10.

4. Lawsuits allege genetic testing labs misled patients about the accuracy of embryo screening tests. STATNews. Published 2023. https://www.statnews.com/2023/07/10/lawsuits-embryo-genetictesting-pgt-a-misleading/

4. Gleicher et al., Feril Steril 2015;104Suppl 3:e9

5. Yang et al., Nat Cell Biol 2021;23 (4):314-321 and Author Correction: (11):1212

6. Barad et al., Hum Reprod 2022;37(6):1194-1206

7. Greco E, Minasi MG, Fiorentino F. Healthy babies after transfer of mosaic aneuploid blastocysts. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2089-2090. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1500421

By Norbert Gleicher, MD , Medical Director and Chief Scientist at The Center for Human Reproduction

in New York City. He can be contacted through The Reproductive

Times or directly at either ngleicher@thechr.com or

ngleicher@rockefeller.edu

BRIEFING: Medical and science journals are supposed to fulfill certain basic functions: They are to report on medicine and science, respectively. They are to do so at highest standards, guaranteed by a detailed objective peer review process, overseen by an unbiased team of editors, and using the best available study methodologies. Biases in publishing have always existed and will, likely always exist because, at least some biases are unconscious, and others may be unavoidable. This article now, however, argues that political biases have started to increasingly overwhelm medical and science journals and must be better controlled.

Introduction

When we previously in these pages on repeated occasions pointed out political biases of medical and science journals, we did so usually within the framework of a broader question—namely, whether these journals should, indeed, “be political” at all? And if up to us, the answer would be a very blunt NO.

Politicking should be left to general news media, just as those, of course, are not in the business of publishing medical and/or scientific papers. At a time when medical and scientific publishing for several good reasons is under increasingly heavy criticism, including shoddy peer reviews and, therefore, often misleading papers and skyrocketing retraction rates, and an explosion of predatory, solely financially-driven journals, we feel strongly that medical and science journals should concentrate on what they were founded for— the critical and carefully peerreviewed publication of important medical and scientific news.

In many ways, this would follow the old-fashioned example of general publishing—to, supposedly, be objective, unbiased (i.e., on neither side of an argument), and not news-interpreting, but evidenceand data-driven. This is, of course, a publishing model many—if not most—of today’s journalists and news organizations have officially and formally discarded (among those publicly, for example, The New York Times) after reaching the (in our opinion, very wrong) conclusion that, under current societal conditions, for a variety of “righteous” reasons, maintaining balance and evenness (i.e., objectivity of reporting) between two opposing arguments has in many instances become impossible without becoming an accomplice to something extremely evil.

It, therefore, is not very surprising that medical and science journals embraced the same philosophy and have steered their journals toward openly taking positions toward opinions they consider righteous, honorable, and an absolute ethical duty to profession and society as

a whole. In short, ideology has conquered many of our leading medical and science journals to the detriment of evidence-based science.

While the process initially was led by some prominent journal editors, it quickly also captured the boards of sponsoring professional societies and of commercial publishing companies, leading to the appointment of a new generation of ideologically quite radically committed editorsin-chief, including Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD (JAMA journals), Eric J. Rubin, MD (The New England Journal of Medicine), Holden Thorp, PhD (Science journals), Richard Charles Horton, BSc, MB, ChB (The Lancet), Magdalena Skipper, PhD (Nature journals) and, maybe the most biased of them all, Kamran Abbasi, MN, ChB, FRCP (The BMJ), and—of course— innumerable others. In contrast, not even a single prominent senior

journal editor, even remotely associable with the political right, comes to mind.

To the contrary, even oldfashioned, politically middle-ofthe-road editors have become unacceptable. JAMA’s highly regarded editor-in-chief for over 10 years, Howard Bauchner, MD, was in 2021 unceremoniously relieved of his duties by the American Medical Association (AMA) after his longstanding deputy editor, Ed Livingston, MD (not even Bauchner himself) hosted what then was considered a politically incorrect JAMA Network podcast on racism in medicine and even though Bauchner issued a public apology for something he—personally—had absolutely nothing to do with. Quoting from an editorial at the time in The BMJ (more on this editorial later),1 the JAMA podcast had been promoted in a tweet as, “no physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in healthcare? An explanation of the idea by doctors for doctors in this user-friendly podcast.”

It featured Livingston in a

discussion with Mitchell Katz, MD, then president and CEO, of New York Health and Hospitals and—concomitantly—a deputy editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. As one would hope for in an announced “debate,” both JAMA editors disagreed on the subject of discussion: Livingston felt that the problem was socioeconomic status rather than racism, while Katz reflected the politically more correct opinion that racism existed and must be eliminated (Bauchner was, of course, nowhere to be seen or heard). Trying to be informative and balanced in its editorial, before publishing it, The BMJ asked the JAMA Network to view or read a transcript of the podcast but was refused “because it had been removed” (so much for transparency in the AMA).1

Bauchner’s leadership of the JAMA Network and for a restructuring of JAMA’s editorial staff. The petition, moreover, asked for scheduling town hall meetings with “black, indigenous, and people of color patients, health care staff, and allies.” And the AMA, of course, complied! Bauchner’s and Livingston’s tenures at JAMA were terminated!

Reporting on these developments in its own liberally-biased ways, The New York Times described those events in a headline as, “editor of JAMA leaves after outcry over colleague’s remarks on racism” (as if Bauchner was given a choice!) and—going on—noted that, “Dr. Howard Bauchner will step down after another editor suggested ‘taking racism out of the conversation.’”2

And then there was, of course, much more to this story: According to The BMJ editorial, following this event, over 7,000 people (it remained unstated who they were) signed a petition on Change.org, organized by an organization called the Institute for Antiracism in Medicine, asking for a review of

Giving full credit to The BMJ at the time (unfortunately, things—as will become obvious below— have since significantly changed with the appointment of a new editor-in-chief), the editorial also included this additional important information, reflective of The BMJ’s at the time balanced and unbiased reporting: “The Institute for Antiracism in Medicine was founded by three Black women physicians in Chicago in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 death of George Floyd at the hands of police. The institute says it is a “civil rights organization dedicated to the abolition of racism in the field of medicine.” We have never heard about it since!

A lengthy search by the AMA, unsurprisingly, led to the appointment of another Black woman physician-

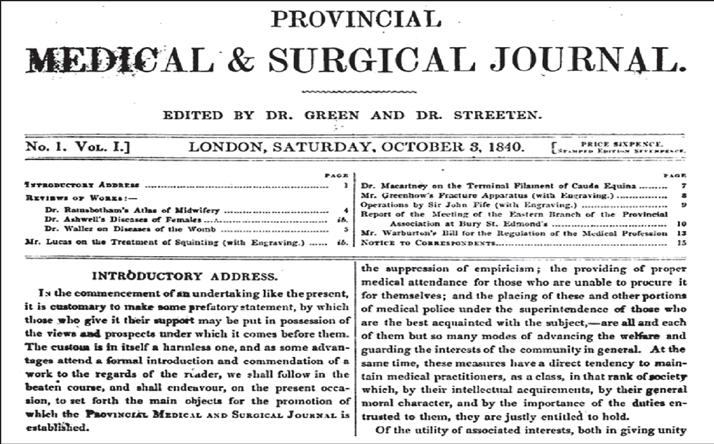

scientist with, of course, a liberalleftist bend. Kirsten BibbinsDomingo, PhD, MD, became Bauchner’s successor and the 17th editor-in-chief of JAMA and other JAMA journals (according to AMA insiders, men were asked not even to apply for the position). But this is, of course, not the end of the story yet—though we now move from JAMA (impact factor 63.1) to its British counterpart, The BMJ (impact factor 93.7). Both are very prestigious general medical journals—simply another way of describing a journal with a high impact factor. The BMJ started in 1844 as the 16-page-long (see right its first front page).

When she retired at the end of 2021 and handed her position over to her longstanding associate editor, Kamran Abbasi, MN, ChB, FRCP, things, however, very quickly started changing. A highly intelligent and excellent writer, Abbasi instantly imposed his personal political imprint on the journal, which in the U.K. often is even significantly more leftistradical than in the U.S. Abbasi’s BMJ and Richard Charles Horton, BSc, MB, ChB’s, The Lancet (impact factor 98.4) are currently, indeed, the politically likely

The journal’s 16th editor-inchief between March 2005 and December 31, 2021, and editorial director for all other BMJ journals, Fiona Godlee, FMedSci, became during her tenure a medical publishing legend—not only because she was the first female editor-in-chief of an important medical journal at a time when women were still a rarity in such editorial positions, but because of how she ran The BMJ and the other journals by innovating medical publishing in traditional, equitable, and balanced ways.

most radically biased prominent published medical journals (see photos of both of their editors to the right). In a recent Opinion article in The BMJ, Abbasi, for example, showed no hesitation to encourage medical journal editors “to resist CDC order and anti-gender ideology,”3 and the background for his article is,

indeed, very relevant and revealing: The Trump administration, of course, has become aware of the “liberal biases” in many prominent medical and science journals. And to say it bluntly, some of the administration’s responses, unfortunately, were not very smart: Demanding withdrawal and/or retraction of already published papers by employees of the CDC because of “forbidden terms” was a good example. One on this occasion, indeed, cannot even argue with Abbasi calling the effort “ludicrous” (though we would not, as he also did, call it “sinister,” which, of course, is reflective of his personal biases).

The silly order was issued by Sam Posner, then the CDC’s associate director for science (an appointee of the prior administration, who less than a month later stepped down) and, paradoxically, also responsible for publishing a medical journal, the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report of the CDC. He referred in his written order to “forbidden terms” in principle to terms regarding transgender care of children and young adults following an Executive Order on the issue by President Trump. Had Abbasi (and another BMJ editor, his co-author) pointed out the stupidity of this obviously failed order and then stopped, we, of

course, would have fully agreed with their Opinion article. But that, of course, was not the case: Abbasi and co-author could not help themselves and ended up descending deeply into the gutters of leftist political polemics. And— as noted above—this is not where medical publishing should end up.

And we are quoting from their gutters: “Make no mistake (as a reminder, Posner issued the order in response to an Executive Order from President Trump expressing opposition to often irreversible transgender treatments of children and minors)—this instruction is not about defending women or women’s rights, as the Trump Executive Order implies. It is part of a broader complicity of this U.S. government and other political and religious conservatives with anti-gender ideology that seeks a return to fundamentalist values. Exceptionally well-funded, wellconnected, and growing globally, the anti-gender movement actively opposes pro-equity efforts, threatening women’s sexual and reproductive rights, LGBT rights, and gender equality—and thus health—worldwide. Gender is being dangerously weaponized. Like Trump’s censorship of CDC scientists, journals and editors must resist this too.” What is there left to say?

How the Gaza conflict has been depicted

One, therefore, of course, can also not be surprised that—this time as the only author—Abbasi used his position as editor-in-chief of The BMJ to take sides in the IsraelHamas conflict over Gaza and,

of course, did not take Israel’s.4

And we are quoting again from his recent Editor’s Choice article under the heading, “a journal’s job:” “Contempt for facts, science, and evidence does not put America or Americans first; it places political and personal agendas first. This agenda-driven approach is enabling mass death around the world and starvation in Gaza. The U.S. is isolated as the prime supporter of a regime that, despite its status as a democracy, is inflicting starvation and, according to Amnesty International, committing genocide in Gaza.”

Obviously expecting to be criticized for his “outspokenness” (many would call it blatant Jew-hatred), he astutely asked the right question (we already above acknowledged his intelligence): “why does all of this matter for a medical journal?” And he then, of course, gives the expected answer: “Mass death and starvation do matter to a medical journal. Reporting on wanton destruction of health facilities, and on the killing of health professionals and humanitarian aid workers, is the business of a medical journal. Political decisions, as we see most vividly in Trump’s administration, directly and indirectly affect health and wellbeing.

Addressing the political determinant of health is firmly in a medical journal’s lane. Medical journals that avoid the impact of political decision-making on health are not doing their job.” Abbasi, of course, considers himself fully qualified not only to express these opinions, but also feels qualified to single-handedly

make the decision that his personal opinion is worth the paper of the prestigious medical journal he edits. Like most serious medical journals, The BMJ claims—for obvious reasons—to publish only peer-reviewed articles. Yet, many of the above-quoted statements in Abbasi’s article cannot withstand even rather superficial scrutiny. An obviously ridiculous analogy would be the publication of a prospectively randomized study on, for example, in vitro fertilization (IVF) in the news section of The New York Times after acceptance by the editor-in-chief of the newspaper because IVF, of course, is a subject of public interest—as recently documented by the paper’s publication of a very interesting, though incomplete, three-part series of articles on the subject of IVF, as we previously noted in these pages.

In contrast to Bauchner’s inappropriate termination for really absolutely no valid cause at JAMA, considering the very obvious Jew hatred expressed in Abbasi’s article (we in this context prefer this term over the term antisemitism), this article—specifically linked to his position as editor-in-chief of The BMJ—in our opinion disqualifies him from continuing in his position and should have led to his firing. Considering the current political circumstances in the UK and the current UK government, this would, however, be too much to expect. Which brings us to The Lancet, and its already very long-lasting editorin-chief, Richard Charles Horton, BSc, MB, ChB, who already in 2014, based on content published in The Lancet, was accused of blatant

antisemitism. He at the time saved his job only through an “emergency trip” to Israel at the invitation of Israeli physicians and—following two days in Israel—after professing “a new understanding of Israeli realities, and especially of the complexities of the Arab-Israeli conflict, pledging for The Lancet a new relationship with Israel.”5 Extending credit where credit is due, Horton held up to his commitment; that is, he did so until very recently. He shortly after October 7, 2023, in his almost weekly Offline commentary, indeed, made the following rather remarkable and insightful comments:6

“Marches for Palestine are taking place across the world. People are protesting at the worsening humanitarian crisis in Gaza and the accumulating deaths of Palestinians from continued Israeli bombing (over 5000 and rising). But what is surprising is how quickly we have forgotten the horror of the attacks by Hamas on Oct 7, 2023. Israeli forensic scientists are still trying to identify the charred bodies of those burned during Hamas’ savage incursion into Israel. Children and their parents executed. Evidence of torture. And 222 hostages, 30 of whom are children or adolescents.

Hamas claims that it does not deliberately kill civilians. Plainly, that is a lie. Nobody can justify their actions as “legitimate resistance”. It was terror, pure and simple. As Israel’s Association of University Heads has written, what happened on Oct 7 was not “one more event in the ongoing conflict between Israelis and Palestinians.” It was “an act of singular barbaric violence which must be thoroughly

renounced.”

So why are there not marches to call for the end to Hamas’ violent rule over Gaza? Why are there not protests at the brutal violence inflicted on innocent children, women, and men on Oct 7? This disturbing asymmetry of outrage weakens the case of those calling for a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas. Those marching in western capitals do not understand the terrorist culture that is projected by Hamas into almost every aspect of life in Gaza. During my visits, I saw medical clinics adorned with pictures of not only Yasser Arafat, but also Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden. I walked in streets where pictures of ‘martyrs’ in combat clothes and with machine guns held across their chests looked down over children walking to school. Men in balaclavas carrying assault rifles paraded unhindered. This is the environment Hamas has created and into which every new generation of Gazan children is born. It is an environment that nurtures and propagates terror.”

And he also must be given credit when foreseeing the quagmire that Gaza has become, when already in October of 2023 also writing: “And yet although Israel’s plan to launch a ground offensive may physically eliminate Hamas, it will not succeed politically. As the deaths of Palestinian civilians mount, so will the number of radicalized young Gazans willing to sacrifice their lives in retaliation. We know who the principal victims of a ground war will be—women and children.

As The Lancet’s 2021 Series on Women’s and Children’s Health

in Conflict Settings underlined, the changing nature of warfare— explosive weapons in urban settings, the instrumentalization of health services in war—leaves women and children especially vulnerable. Khamis Elessi and colleagues reported in 2017 that the 2014 conflict in Gaza led to the deaths of 530 children, a quarter of the total killed. Most of these children died at home, sleeping, eating, or just sitting with their families. Aside from these direct effects of war, the indirect effects are also substantial: displacement, disrupted water and electricity supplies, malnutrition, infectious and chronic diseases, and deteriorating mental health. In Gaza, these damaging health impacts will not be imposed on healthy communities. Gazan population health is already poor— childhood anemia, suboptimal maternal care, poor mental health services, weak infection control, and vitamin deficiency, all compounded by a fragmented, depleted, and brittle health system.”

Almost a year-and-a-half later, by February 2024, he in a new Offline article wrote, “We all abhor unpleasant deals, but that’s what must happen if we are to solve the Gaza crisis.”7 And since then the coverage of the conflict has been getting progressively more antiIsraeli—not through Horton’s own words, but through selection of accepted articles and letters which have become very one-sided proHamas. One issue in June of this year included three independent very unfriendly articles toward Israel to call it out mildly,8-10 though a letter in the same issue also attempted to create some balance.11 Obviously still sensitive to past

accusations of antisemitism, not wanting to put his own name to it, Horton, however, on May 24, 2025, published a rare unsigned Editorial in The Lancet under the title, “Gaza has been failed by silence and impunity,” accusing the Israeli government of “for too long having acted with impunity,” and quoting a surgeon of “having witnessed many examples of clear Israeli war crimes.”12

Yet not a word about the remaining Israeli 53 hostages in Gaza, of which at least 30 have already with certainty been murdered, and only between 20 and 23 may still be alive (isn’t it amazing that the world does not even demand to know who still is alive?) And, of course, not a word in The Lancet about the Red Cross having not visited even a single hostage in Gaza detention since October 7, 2023, and—actually— not even having tried to do so. The world very obviously does not care very much about the Jewish hostages in Gaza. And, Dr. Horton, we are seeing through the charade; The Lancet under your leadership, of course, also does not care!

Likely reflective of U.S. public opinion polls which still signal large majority support for Israel over Hamas in comparison to European countries, U.S. medical and science journals have paid much less attention to the Gaza conflict than their British counterparts, though if there was a trend apparent, it also favored pro-Palestinian voices in numbers of articles that appeared in print. That American journals also have become more woke is also demonstrated by the choice

of writers for invited opinion submissions. For example, The New England Journal of Medicine and other medical as well as science journals have routinely published opinion papers hostile to the Trump administration, not infrequently several in one issue of a journal—though rarely, if ever, an article supportive of positions taken by the government.13-15

Likely the best example has been how the American journals have handled gender transition treatments: In stark contrast to European countries, where, with the publication of the Cass Review in the UK,16 the dam broke, and European countries almost uniformly stopped gender identity services for children and young people, while in the U.S. prominent medical journals still continued to publish articles in full support of such services.17,18 Interestingly, the most recent article by U.S. physicians taking such a position was published in The Lancet. 19

Since medical and science journals have almost uniformly decried the cut-off of federal funds to universities and colleges in response to obvious administrative neglect of administrations to protect their Jewish students from Jew-hating students and agitators on their campuses,20 the developing conflicts between leading universities like Harvard and Columbia and the Trump administration also deserve here some attention. A quick literature search we performed on PubMed was unable to locate even one single paper in medical and/or science literature on the subject— except for some marginal papers in the psychiatric literature and in Jewish community journals. The

subject, simply, does not exist in the medical and/or science literature.

Considering the resurging worldwide antisemitism, of course including in the U.S., this rather remarkable observation should really not surprise. The finding is, however, double-telling, considering what prominent journals, like The BMJ and The Lancet, have been claiming about their journals’ obligations in cahoots with academic medicine “to champion diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility”;19 But, of course, only until it also would involve the Jews! Hypocrisy, of course, reigns at these journals.

1. Editorial. BMJ. 2021;372:n851.

2. Mandavilli A. Editor of JAMA Leaves After Outcry Over Colleague’s Remarks on Racism. The New York Times. June 1, 2021.

3. Clark J, Abbasi K. BMJ. 2025;388:r253.

4. Abbasi K. BMJ. 2025;389:r1176.

5. NGO Monitor. Oct 2, 2014. https://ngomonitor.org/press-releases/ending-thelancet-s-role-in-demonization/

6. Horton R. Lancet 2023;402(10412):1511.

7. Horton R. Lancet. 2024;403(10425):420.

8. Zarocostas J. Lancet. 2025;405:2038.

9. Paris et al. Lancet. 2025;405:2041–4.

10. Jamaluddine et al. Lancet 2025;405:2048.

11. Zivot et al. Lancet. 2025;405:2057–8.

12. Editorial. Lancet. 2025;405:1791.

13. Yamey et al. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:1457–60.

14. Goldman M. Axios. Feb 6, 2025. https://www.axios.com/2025/02/06/ academic-journals-push-back-on-trump

15. Vergano D. Sci Am. Apr 2, 2025. https://www.scientificamerican.com/ article/trump-administration-attacks-onscience-trigger-backlash-from-researchers/

16. Cass H. Cass Review. Apr 10, 2024. https://cass.independent-review.uk

17. Budge et al. J Adolesc Health 2024;75(6):851–3.

18. Aaron et al. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:526–8.

19. Salles et al. Lancet. 2025;405:2033–6.

20. Reardon S. Science 2025;388(6745):342–5.

By Norbert Gleicher, MD , Medical Director and Chief Scientist at The Center for Human Reproduction in New York City. He can be contacted through

the

VOICE

or

directly at either ngleicher@thechr.com

or

ngleicher@rockefeller.edu

.

BRIEFING: Norbert Gleicher, MD, the Medical Director and Chief Scientist of the Center for Human Reproduction (CHR) in NYC, offers here a quite challenging analysis of current IVF practice. Building on the fact that live birth rates in fresh autologous IVF cycles in the U.S. (and in most other parts of the world) have been declining from an all-time peak around approximately the years 2010 – 2011, while IVF cycle costs have been dramatically increasing, he is pointing out the main reasons for these developments. And they are likely not what you expect!

“Developing” not “engineering” should be the goal of infertility practice

For several reasons—intending to present to its readers recent innovations in IVF and reproductive medicine—a relatively new virtual newsletter caught our attention. First, because we had found earlier issues of this newsletter quite interesting and, at least on one occasion, had already referred to an article in one of our medical literature reviews in the VOICE But the principal reason why this article had a special impact (we will later discuss one more important reason) was only a few words in its heading, which were supposed to convey its principal purpose— “engineering the future of reproductive medicine.”1

What was then so special about these six— obviously very innocent sounding—words?

The answer may surprise because, having especially in most recent years become increasingly convinced that infertility practice over the last 20 years has stagnated and, in many ways, even regressed, these six words perfectly crystallized the reason for this stagnation: Instead of “developing” the infertility field further, infertility practice has for much too long been trying to “engineer” the future of the field.

With both of these words on first impression potentially appearing to have very similar meanings, what then could be an important enough difference between “developing” and “engineering” the future of infertility practice? The answer may once again surprise because the difference is not only—as we in medicine are used to striving for—statistical significance; on more careful reconsideration, it is, indeed, much more profound than that.

Let me explain: Anything we engineer is based on a purpose. We are engineering a building to live or work in, a car to drive us from point A to point B, an elevator to allow us to avoid stairs, and a toothbrush to clean our teeth. But engineering a device or even a process in support of achieving a goal is always the second or even a third step in the development of an

end product. Long before the engineering process can start, there—first of all—usually must be a need. Then, as a second step, a hypothesis is developed on how this need theoretically may be remedied.

This may include the building of models, all kinds of calculations based on solidly established rules of physics, economics, etc. (i.e., that a properly engineered car would not drive is basically impossible; that a properly engineered building would collapse is unthinkable). In other words, engineering can bring a high degree of confidence in achieving a goal that, not long before, may have existed only as a small spark in the imagination of a visionary (think Elon Musk—by training, an engineer—when he first envisioned an electric car). By the time Musk and his team developed the blueprints for the first Tesla model, there was strong reason to believe the car would function well, could be produced efficiently, and might even turn a profit.

But medicine (and science in general) is different: Here, everything, of course, also starts with a need, followed by a hypothesis about how to resolve this need. This hypothesis, however, cannot solely rely on previously confirmed laws of physics, biology, economics, etc. As medicine and science in general never have the same certainty that engineering has in its underlying tools, any medical idea and/or concept, of course, must be scientifically confirmed before

formally entering clinical practice.

Yes, we can plan studies to test a new drug, a new treatment algorithm, a new surgical procedure, or a new test, and we can do these studies at the highest and most expensive evidence levels (prospectively randomized studies) or lower levels (other study designs). But we will never even come close to the certainty of success of a well-engineered project because even the best prospectively randomized clinical trial will not and cannot apply to every potential patient.2 Yet, even a just decently engineered car will still always drive, and even a just decently engineered building will still likely not collapse, whoever enters. And, while some toothbrushes may last longer than others, all can at least be used for some time.

In other words, if a process is initiated or a product is launched based on solid engineering, the expectation is that this endeavor will offer an expected outcome. In medicine, even if the best tools are used in attempts at confirmation of effectiveness, this same level of certainty can never be achieved. And this is the case even under the best of all circumstances. One can imagine how unlikely expectations will be met if confirmatory tools used to show the efficacy of a medical treatment are not even at the highest evidence level. Or—as in the last 20 years in fertility practice has happened over and over again—a large number of treatments, called “add-ons,” have been brought into clinical IVF practice with at times highly exaggerated claims—simply based on brilliantly sounding hypotheses, though without confirmatory studies.

And the most frequent reason why this has been happening—and not only in reproductive medicine— was, indeed, the incorrect assumption that medicine can “engineer” progress by—like engineers—simply building on irrefutable evidence and experiences from the past. As convincing as this past evidence may appear, it may not be applicable for several reasons: It may have been obtained in a different patient population, under different conditions, and with known or even unknown co-dependencies. Even engineering understands that universality is not limitless: While still applicable to a large number of structures in a given geographic risk area, engineering requirements for buildings in an earthquake zone will, for example, universally be more stringent.

Individualization in medicine is, however, a much more profound need than in engineering (not so, however, with architecture and interior design) because individual patients can, of course, vary from each other to highly significant degrees—even if they are neighbors.

The false assumption that we can “engineer” clinical practice by simply extrapolating from past intellectual experiences has been at the core of practice patterns that not only have been fully integrated into routine IVF but have become a dogmatic component of this most important infertility treatment, such as (and more on those below) the general concept of embryo selection, routine culture of embryos to blastocyststage, exclusively single embryo transfers, routine preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A, in increasing numbers of clinics, indeed, mandated), embryo banking in place of fresh embryo transfers, time-lapse imaging, endometrial receptivity testing, etc.

All of these practices (and many others), unfortunately, have universally gained in popularity, even though increasing evidence has been developed demonstrating that their alleged outcome benefits in IVF cycles don’t really exist. As already noted, this evidence—more often than not—moreover, suggested that most of these “add-ons” in selected subpopulations of patients, indeed, adversely affect IVF cycle outcomes and lead to declining live birth rates all over the world in autologous fresh IVF cycles.3 They, moreover, of course, also increase costs—the result being that IVF cycle costs have steadily increased, while IVF cycle outcomes have been steadily declining.

Unsurprisingly, these two trends have been accelerating in parallel with the growth and development of a financially strongly motivated support industry for the infertility field, and especially IVF, which by now has even penetrated clinical IVF through non-professional (i.e., non-MD) ownership of fertility clinics. A recent Lancet editorial noted that in the U.S., already over a third of all IVF cycles are done in clinics owned by private equity firms and that PGT-A is done more frequently in equity-owned clinics,4 an observation recently also reported by the CHR’s investigators.5

Leading—as noted in the introduction—to stagnation and even regression in IVF cycle outcomes worldwide, including in the U.S.5 “Engineering” the future of reproductive medicine and especially infertility practice, therefore, is exactly what must be stopped, hopefully to be replaced by organic “development” of truly best-evidence-based practice—fully recognizing that best evidence never can be perfect but—at absolute minimum—must be transparent and honest.

The remaining part of this communication will outline how big parts of what has become routine worldwide IVF practice are really useless and wasteful “add-ons” to IVF, often even damaging to patients’ IVF cycle outcomes. Most of these integral components of the IVF process are still increasing in utilization in routine U.S. clinical practice.

It all started in the early days of IVF when the concept was born that every oocyte/embryo cohort in an IVF cycle must have a “best” egg/embryo. Who invented the concept and when is unclear; the concept—or should we better call it a hypothesis—however, has dominated IVF-related research and clinical practice since the early days of IVF. It, however, got supercharged by what has likely been the most damaging publication to the IVF field ever: the paper published in the year 2000 by Gardner and Schoolcraft (with 3 more co-authors), in which the authors concluded—and we are quoting: “The ability to transfer one high-scoring blastocyst should lead to pregnancy rates greater than 60%, without the complications of twins.”6 To the detriment of the IVF field, this paper unfortunately exerted a very significant influence on IVF practice worldwide and, indeed, does so to a degree to this day.

Even though a quarter century after this publication, it has become indisputably obvious that practically everything about this paper was incorrect, remarkably, neither the authors nor the journal where the article was published has found it appropriate to withdraw the paper, or at least to publish a correcting commentary. This now must be stated loud and clearly because everything about the concept/hypothesis of embryo selection has since been established as

biologically, physiologically, clinically, and ultimately, mathematically incorrect and, therefore, has become indefensible. To the applause of a surprisingly large number of colleagues, we here at the CHR, indeed, made this argument in a recently published paper in the medical journal Human Reproduction Open. 7

Gardner and Schoolcraft’s paper not only turbocharged the concept of embryo selection but also initiated a worldwide IVF practice change from routine day-3 cleavage stage transfers to day-5 (and now up to day-7) blastocyst-stage transfers, both practice patterns which by now have been indisputably demonstrated not to improve IVF cycle outcomes, yet are now by a large majority of IVF practitioners still considered practice dogmas. This opinion still prevails, even though nobody but highly selected good-prognosis patients— likely representing only approximately 15% of a general patient population at most—will demonstrate alleged pregnancy rates in the original paper (which had studied only best-prognosis patients), while a much greater percentage of women will actually lose pregnancy chances to a significant degree because none of their embryos will survive in vitro culture to blastocyst-stage (the still-made argument by some proponents of blastocyst-stage culture that this is due to poor embryo laboratory practices has been solidly rebutted!).

But the damages caused by the Gardner and Schoolcraft paper to IVF practice do not end here: Blastocyst stage embryo transfer, as noted in the above quotation of their abstract summary, also favors elective single embryo transfer (eSET) because it minimizes twin pregnancies. And twin pregnancies, of course, are widely (even by ASRM and ESHRE)— because they allegedly “increase pregnancy risks to mothers and babies”—considered a really bad IVF outcome.

This widely held belief has, however, also been solidly rebutted once the singleton-to-twin pregnancy comparison is conducted statistically correctly. Historically, that has not been the case in most published papers alleging increased twin pregnancy risks because these papers incorrectly compared apples and oranges—the birth of one child to the birth of two children. If compared correctly (one twin to two consecutive singleton pregnancies), the alleged increased risks to mother and offspring

basically disappear.8 Many potential mothers (and their partners) with longstanding infertility, of course, would like twins more than anything else. Twins, therefore, can become a wonderful choice for patients—of course, only if mothers have the physical health to tolerate the increased physical stresses of a twin pregnancy.

And then there is, of course, PGT-A, a procedure currently likely the most expensive, useless, and often, even harmful addition to IVF practice, now already used in more than half of all IVF cycles in the U.S. Again, basically another disproven hypothesis that was allowed to become a routine part of IVF practice without any evidence that claims made in its favor were supported by serious scientific evidence. In addition, PGT-A is, of course, yet another embryo selection method alleged for over 20 years to improve IVF outcomes, which has been proven to do nothing like that, as even the ASRM had to finally acknowledge: It does not improve pregnancy rates, nor live birth rates, nor miscarriage rates, nor even time to pregnancy.9

For unclear reasons, the ASRM described blastocyststage culture (in place of cleavage-stage culture) as the standard of care in IVF. Proponents of PGT-A, therefore, have argued, if we already are culturing embryos to the blastocyst stage, why not at the same time also biopsy them for PGT-A, and freeze them rather than transfer them fresh.

So-called all-freeze cycles—in place of fresh embryo transfers—have become another “fashion of the moment” in IVF, even though scientific evidence quite categorically demonstrated that alleged IVF cycle outcome improvements are pure fantasy. And, yes, PGT-A, of course, adds at least $5,000 to the IVF cycle bill, which usually is not covered by insurance, even if the IVF cycle is covered. And all-freeze cycles, while they are alleged to save the embryo transfer fee, what frequently remains unmentioned is the added embryo freezing fee and, of course, the completely new additional cycle charge for a frozen-thawed cycle. In short, already unreasonably high IVF cycle costs in the U.S. just continue to increase without offering any outcome benefits.

We previously alluded to the fact that infertility practice—and especially IVF practice—in the U.S. and elsewhere in the world is increasingly owned by investors rather than physicians and/or academic institutions. We also noted the service industry that has arisen around infertility practice and IVF. In its early days, it was mostly restricted to pharma companies producing fertility medications. But while their influence on the fertility field has radically declined, the field has witnessed significantly increasing influence especially from genetic testing companies and private equity companies which are buying up fertility clinics in efforts to establish national networks, and from conglomerates that own provider networks in conjunction with other support services, such as genetic testing companies, financing companies for fertility services, and even insurance companies covering fertility services.

Their influence on ASRM in the U.S., ESHRE in Europe, and other professional societies in other parts of the world is steadily growing. The unsurprising consequences are, of course, not always the best for fertility practice because the loyalty of these companies—understandably—is first and foremost to their investors, which in practical terms means to maximal sales of their products rather than to the overall improvement of fertility services and—for example—improvements in IVF cycle outcomes.

Within this context, one kind of company deserves special mention, and that is the single-product company. Here is one historical example to make a point: It was one at the time Scandinavian company that brought the first so-called embryoscope to the market and, by doing so, in a sense revolutionized how most embryology laboratories work. The company at the time presented the concept of a closed incubation system that did not require much intervention between fertilization and blastocyst stage and timelapse imaging of embryos as the new panacea for IVF that would make everything in conjunction with IVF better: better embryology overall, better blastocyst rates, all—of course—resulting in better pregnancy and live birth rates, savings in embryology time per patient, other cost-savings, etc.

None, of course, was ever confirmed. Indeed, to the contrary, what was confirmed is that these systems did nothing of what had been promised, though they, of course, allowed for interesting observations in human embryo development and, therefore, turned out to be an at times valuable research instrument.10

But by the time all of that had become obvious, most embryology laboratories had already spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on these systems and, indeed, a whole bunch of companies had started manufacturing them. In other words, the marketing effort of one single company (and, of course, the investment of its owners) not only had created a new industry, but at the same time had dramatically affected the cost of worldwide IVF practice (new equipment costs, of course, had to be amortized) without any of the promised positive effects on IVF outcomes.

And this is only one among many single-product companies that changed the field of IVF based on questionable promises: Igenomix is another such company. Originally founded based on the by now very controversial so-called Endometrial Receptivity Analysis (ERA), the company expanded its offerings shortly thereafter into less controversial PGT-A and several other tests. ERA and PGT-A have, indeed, achieved almost dogmatic adulation from a large number of fertility clinics, even though their clinical effectiveness has been seriously challenged. As noted before, even ASRM has by now had no choice but to acknowledge the clinical ineffectiveness of PGT-A.9 The ERA has not feared any better: After several published studies, the British Human Fertilization & Embryology Authority (HFEA) rated the test red, which means that findings from moderate/high quality evidence have demonstrated that this “add-on” may actually reduce treatment effectiveness in IVF.11

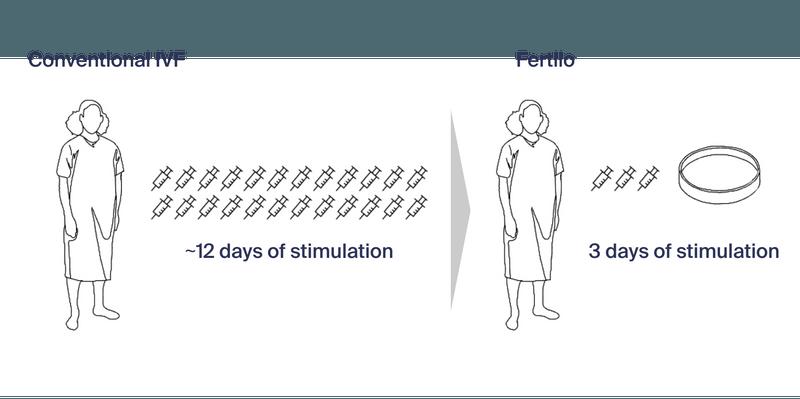

This closes the circle and brings us back to the introduction of this article, where we noted that the inspiration for this article came from the heading of an article in the IVF-Worldwide Newsletter. Though the word “engineering” was the impetus, we also noted that there was an additional issue that attracted us to this article. And this issue was the fact that the newsletter featured an Austin, Texas-based company (with offices in NYC) called Gameto as an “innovator in IVF and reproductive medicine.” This company— at least as of this point—is a new single-product company which, exclusively through press releases, has started promoting its first product called Fertilo. It is, and we are quoting, “an engineered line of ovarian support cells that aid egg maturation, developed by reprogramming stem cells (iPSCs).”12

Quoting further from the company website: “Maturing eggs outside the body could reduce the need for hormonal injections, improving the patient experience and safety while maintaining efficacy.” The figure below from the company’s website illustrates the company’s hypothesis for their new “engineered” product, which, so far, has allegedly only undergone a Phase 1/2 trial (more on that below) and, allegedly, was just FDAapproved for a Phase 3 trial.

And the company then, with carefully chosen wording, notes that, “by making these processes easier and less expensive, Fertilo could lower barriers to adoption of IVF and egg freezing, unlocking more of the market and helping more families reach their reproductive goals.”

We were impressed and pleasantly surprised by the conditional tone of this statement ( … could lower barriers …) because the article in the IVF-Worldwide Newsletter is much less restrained, stating that “Fertilo represents a significant advancement in reproductive medicine, offering a less invasive and potentially more cost-effective alternative to traditional IVF methods.” The wording here—very obviously—is no longer equally conditional, and this is usually exactly what happens when industry starts the marketing campaign for a new IVF “add-on.”

And just to emphasize this point, in explaining that the FDA just approved Fertilo for a Phase 3 clinical trial, the article described this iPSC-based therapy as a “revolutionary breakthrough” and even gives it the very catchy name, the “Gameto Fertilo breakthrough.”1 But is it really a breakthrough? We are not convinced! The CHR has been triggering especially older women after only 1, 2, or 3 days of ovarian stimulation for years. And in this older population, it not only works very well, but works very well without stem cells. And then the Phase 1/2 trial results quoted in the Newsletter’s article (we are unaware of any formally

published data), they really don’t look very good: In 40 patients, Fertilo allegedly achieved a 70% maturation rate for oocytes compared with a 52% rate using standard in vitro maturation (IVM). Is that really a statistically and clinically significant difference? Euploid blastocysts were achieved in 10% of eggs with Fertilo and in only 2% with standard IVM. We would argue that, considering the small number of study subjects, those rates really do not appear to differ statistically and, indeed, seem to be almost equally poor. We also wonder how IRB approval was obtained for the fertilization of human oocytes and the production of human embryos, apparently for research purposes only. Finally, that 8/10 Fertilo vs. only 3/10 standard IVM patients had at least one euploid transferable embryo is in the article presented as “groundbreaking,” is, once again, considering the small patient numbers, to say it mildly and politely, at least a mild exaggeration!

It is this kind of marketing of new products to the IVF community that, unfortunately, has greatly contributed to the many misdirections routine IVF practice has taken over the last two decades. The results have been “add-ons” to IVF, which in a large majority have not improved IVF outcomes and for many patients have actually reduced pregnancy and live birth chances. At the same time, for many, unaffordable IVF cycle costs have already significantly increased, while having to pay ever more for every try.

We, of course, sincerely hope that the Fertilo hypothesis will ultimately, indeed, be scientifically confirmed and lead to a successful, FDAacknowledged product that does all those wonderful things Gameto promises to deliver with Fertilo per website (see below).12

• More natural

• Safer

• Faster

• More comfortable

• Effective

• More accessible

But we, of course, also hope that Fertilo does not become just yet another “add-on” to IVF practice that does nothing but increase costs. It would be so much better if marketing campaigns for new IVF-related products only started after the publication of real and

validated data. That, indeed, should be the law or, at least, the ethical guideline for how innovations are introduced to clinical IVF practice. The future of IVF must be “developed” through solid evidence and not through “engineering!”

1. Shoham Z. IVF-Worldwide Newsletter. https://ivf.cmecongresses.com/innovation-in-ivf-and-reproductive-medicineengineering-the-future-of-reproductive-medicine/

2. Kostis JB, Dobrzynski JM. Am J Cardiol 2020;:109-115

3. Gleicher et al., Hum Reprod Open 2019(3):hoz017

4. Editorial. Lancet 2024;404:215

5. Patrizio et al., J Assist Reprod Genet 2025;42:81-84

6. Gardner et al., Fertil Steril 2000;7396):1155-1158

7. Gleicher et al., Hum Reprod Open 2025(2):hoaf011

8. Gleicher N, Barad D. Fertil Steril 2009;91(6):2426-2431

9. ASRM/SART Practice Committees. Fertil Steril 2024; 122(3):421-434

10. Bhide et al., Lancet 2024;404(10449):P256-P265

11. HFEA. https://www.hfea.gov.uk/treatments/treatment-addons/endometrial-receptivity-testing/#:~:text=Endometrial%20 receptivity%20testing%20involves%20taking,receptive%20to%20 an%20embryo%20implanting.

12. Gameto. https://www.gametogen.com/fertilo/

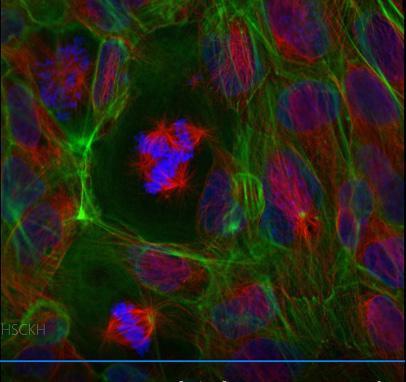

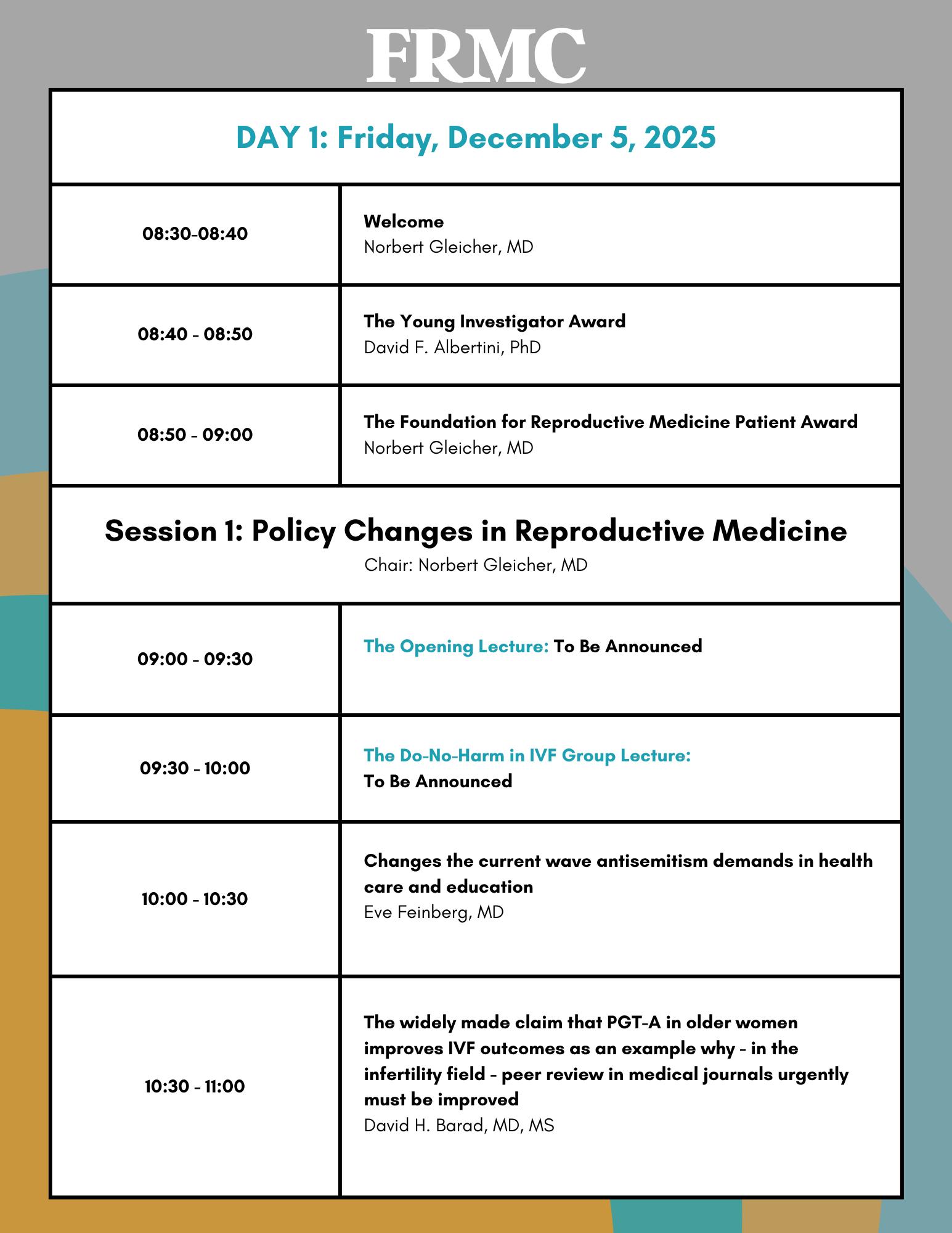

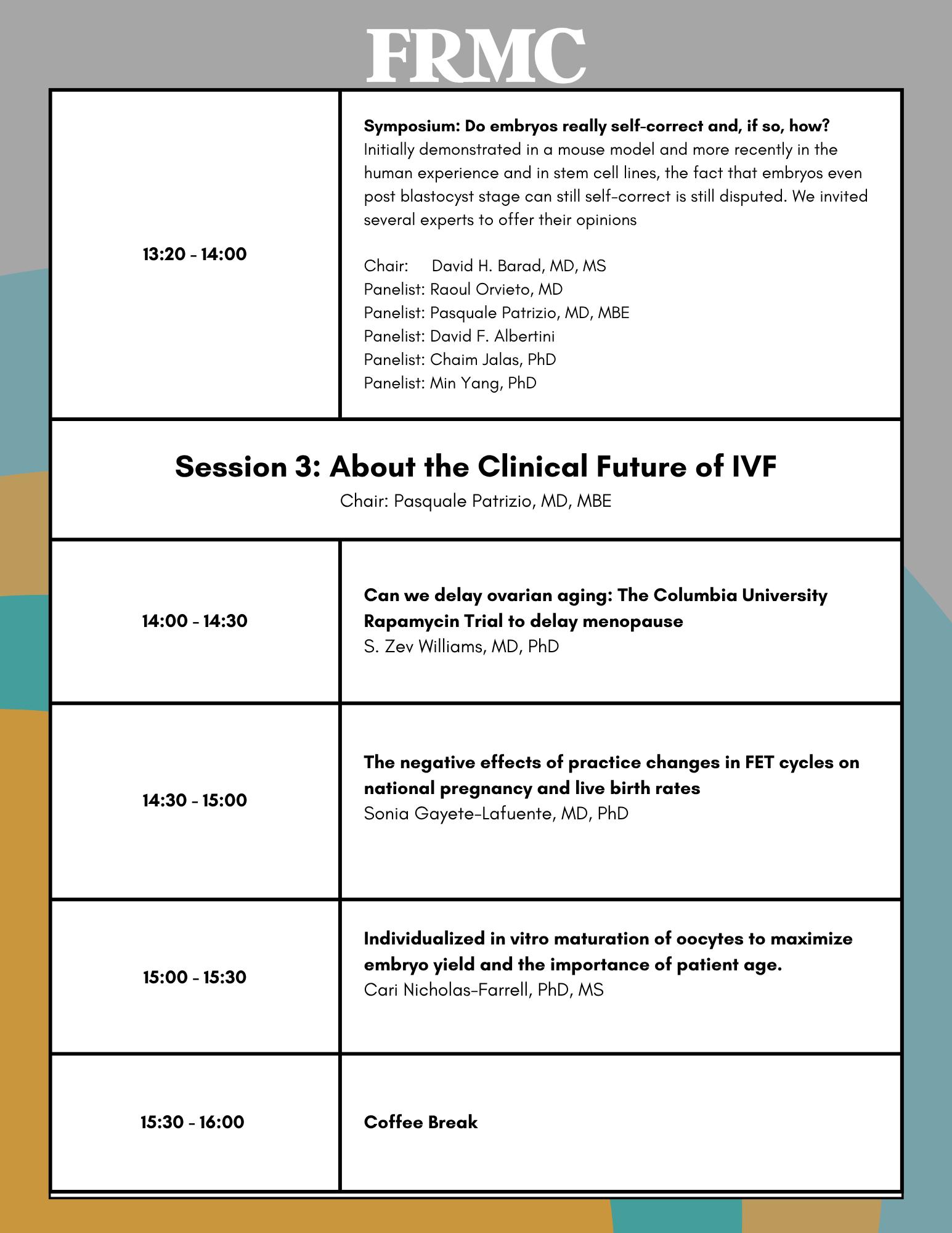

BRIEFING: Our photo gallery this time has the theme, cells dividing every which way! It features possibly one of the most remarkable processes in all of biology and medicine: cell division! While the static images gathered here may tell a story about the working machinery at play when both our genomes (chromosomes) and cytoplasm become perfectly separated into two “equivalent” daughter cells, watching this process in action is something we encourage our readership to enjoy on the internet. The star of this “show” is the spindle-a complex amalgam of cytoskeletal components known as microtubules and actin filaments that under the orchestration of many regulatory molecules see to it that in most cases cell division proceeds according to plan. That this may not always happen can be for better or worse for the products of mitosis or meiosis!

FIGURE 1 demonstrates h14. The infamous HeLa cells shown here sometimes get it “right” and sometimes not. Three dividing cells occupy the center of this image, representing steps in the mitotic process that coordinate chromosome positioning (blue) with microtubules in the spindle (red) and special organizers known as centrosomes (in yellow).

FIGURE II demonstrates tripole. Too many cooks (centrosomes) sometimes spoil the recipe, leading to spindles in this case with three poles, a situation that nearly always will result in an abnormal number of chromosomes in “daughter” cells.

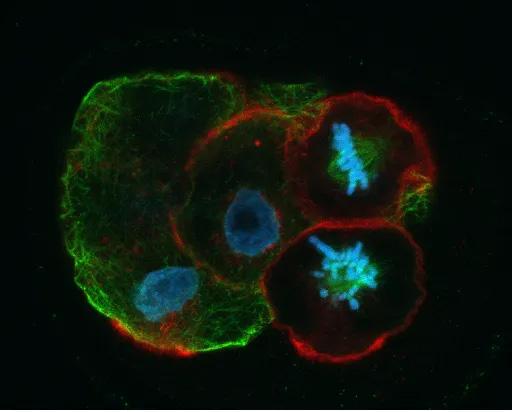

FIGURE III demonstrates Recon. Moving here along from mitosis to meiosis, we capture the meiotic spindle of a human oocyte making a last-ditch effort to corral all of its chromosomes in the midzone of the spindle, so it can get on with the business at hand, to separate bivalents and emitting a first polar body that would genetically position the oocyte in a state of preparedness for fertilization.

FIGURE IV shows kh1d. Once fertilization has occurred, the one-cell embryo or zygote will proceed through a series of mitotic divisions as shown here in a 4-cell embryo in which two of the blastomeres are preparing for the big event! Note the ordered alignment of the chromosomes (blue) on the spindle (green) in the upper blastomere compared to the apparent state of disarray in the lower cell. Errors in mitosis during early embryonic cell divisions are the principal cause of aneuploidy in human embryos.

By Chloe H, BS , is a writer and editor at the VOICE and The Reproductive Times.

of the VOICE or at social@thechr.com

She can be reached through the editorial office

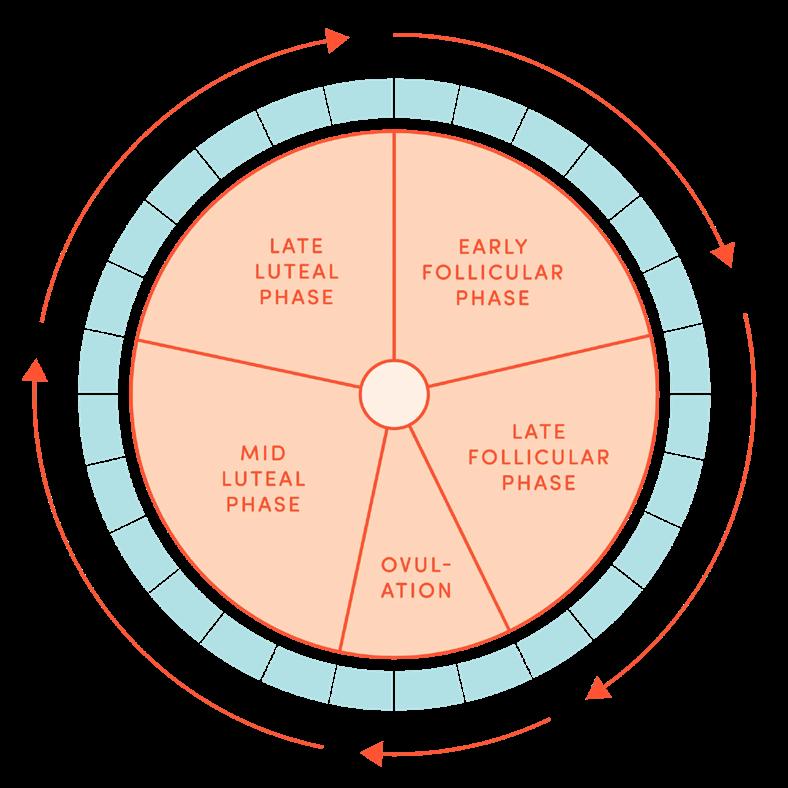

BRIEFING: We’re introducing a new article type to the VOICE , the “Quick Read,” which is meant to inform our readers in a very brief format about an important clinical issue in infertility. Today’s subject is ovulation, the process that, in most women, allows, until perimenopause, almost every month, one ovary (usually alternating between the right and left ovary) to release one egg. It is then “caught” by the distal, fimbriated end of a fallopian tube. Once the egg has successfully entered the fallopian tube, egg, and sperm meet in the distal ampulla of the fallopian tube after sperm has found its way from the vagina, through the cervix and uterine cavity into the tube and then further upwards toward the waiting egg in the tubal ampulla, where then fertilization occurs.

Introduction

When it comes to fertility, timing truly is everything. If you’ve ever wondered why some months seem easier to conceive than others, or why your cycle sometimes feels unpredictable, you’re not alone. Behind the scenes, your body is orchestrating a complex interplay of hormones, lifestyle choices, and daily habits— all of which shape your chances of ovulation and conception. Understanding these factors can empower you to make small changes that can have a big impact on your reproductive health.

Hormones: The chain reaction behind ovulation

Ovulation results from a carefully timed hormonal sequence. In the first half of the cycle, folliclestimulating hormone (FSH) supports follicle development. Rising estrogen levels coming from the growing follicles then trigger a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH), which initiates ovulation.

If stress, PCOS, or undernourishment disrupt this chain, ovulation can be delayed or missed. In PCOS, hormone imbalances and insulin resistance may prevent the LH surge from occurring.¹ Recognizing these disruptions can help you better understand your body’s signals—and know when it’s time to consult your doctor.

The Mediterranean diet, which emphasizes whole grains, vegetables, fruits, legumes, olive oil, and fish, has been linked to improved ovulation and fertility outcomes.² This pattern supports hormone balance and reduces inflammation.

Diets high in trans fats, refined sugars, and processed foods, on the other hand, can disrupt insulin sensitivity and increase inflammation, which may interfere with ovulation.³ A 2021 review found that high-glycemic carbohydrates and saturated fats were associated with ovulatory disorders.³ While evidence is not yet definitive, even small shifts, like swapping refined grains for whole grains, may support fertility and improve overall health.

Moderate physical activity is linked to more regular cycles and better ovulatory function.³ You don’t need to overdo it—gentle, consistent movement like walking, yoga, or swimming can improve circulation and reduce stress. Overly intense workouts, especially with low body fat, can suppress ovulation. Chronic stress can elevate cortisol, which may disrupt the release of LH.³ While stress can’t be eliminated, practices like mindfulness, journaling, or deep breathing can help restore hormonal balance. Sleep is also essential: poor or irregular sleep has been linked to hormonal imbalances and menstrual issues.⁴ Aim for 7–8 hours of restful sleep to support reproductive function.

Getting to know your cycle is one of the most empowering steps you can take. While ovulation typically happens about 14 days before your next period, that’s not true for everyone, and it can change from month to month. That’s where ovulation tracking tools come in. There are a variety of tools available, ranging from simple to high-tech, and each has its pros and cons. A 2017 review categorized the most common ovulation tracking tools into four groups: biological signals, hormone-based methods, physical measurements, and digital tools.⁵

• Cervical mucus tracking involves observing changes in vaginal discharge throughout the cycle. As ovulation approaches, cervical mucus typically becomes clear, stretchy, and egg-white-like, signaling peak fertility. This method is free, noninvasive, and backed by solid science, but it does take a little practice to learn how to interpret changes accurately.