VOICE

IN THIS MONTH’S ISSUE

THE CHR LETTER DOES FEMALE AND MALE FERTILITY REFLECT UPON A HEALTHY LIFE, AS WELL AS LONGEVITY?

A PIECE OF MY MIND: PRIVATE MEDICINE - AT ITS END OR AT A NEW BEGINNING?

WHAT HAPPENS BEFORE IVF CYCLE START IS NOT ANY LESS IMPORTANT THAN THE CYCLE ITSELF

IN RECOGNITION OF INFANT- LOSS AWARENESS MONTH, A FEW WORDS ABOUT MISCARRIAGE RISK, INCLUDING A NEW “CASE REPORT OF THE MONTH”

NEW CHR PUBLICATIONS

QUESTIONS PATIENTS AND THE PUBLIC ASK

THE CHR’S INTERPRETATION OF RECENT LITERATURE RELEVANT

Investigating the association of vitamin D levels in newly presenting infertile women at the CHR, AMH levels were, as the figure demonstrates, inversely related to vitamin D levels: Best AMH levels were associated with lowest vitamin D levels. This unexpected finding, however, almost completely vanished once data were adjusted for female age, suggesting that this initial observation was mostly driven by patient ages and, therefore, did not suggest any causality.

See article on pages 25-28

OCTOBER 2023 THE CENTER FOR HUMAN REPRODUCTION

TO REPRODUCTION 3 11 13 19 21 24 25 29

Figure: Correlation between vitamin D levels and functional ovarian reserve, as assessed by AMH levels

Ribbon for Pregnancy and Infant Loss Awareness Month

The CHR is known as a “fertility center of last resort,” primarily serving patients who have previously failed treatments elsewhere. Among CHR’s areas of special expertise are treatments of “older” ovaries, whether due to advanced female age or premature ovarian aging (POA), immunological problems affecting reproduction, repeated pregnancy loss, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), tubal disease, male factor infertility, etc.

CONNECT WITH THE CHR Missed the last issue of The VOICE? Access previous issues on thechr.com

www.thechr.com @CHRNewYork @CHRNewYork @CHRNewYork 2 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice ADVERTISEMENT

ThE VOICE

We want to thank the unusually large number of readers who commented on our September issue in writing to us. Of course, we welcome any kind of response, however short it may be. We would also like to take this opportunity to remind our readers that The VOICE welcomes the submission of longer pieces for publication, which can be in response to prior articles in the newsletter or may address a new subject in reproductive medicine that is of potential interest to the community of our readers.

We especially value opinions from colleagues that diverge from the opinions held by the CHR and that are routinely reflected in The VOICE because the culture of the CHR fully recognizes the relativity of much of what we do in medicine, even if considered to be routine. Sooner or later, because of newly evolving knowledge, even most routines are replaced.

Per usual, this issue of The VOICE contains a series of articles, answers to questions from the CHR’s patients and/or readers of this newsletter, news about recently in-print CHR publications, and this month again the discussion of a very long list of interesting papers in the medical and scientific literature.

As we announced last month, our lead article this month is about the relationship of female as well as male fertility with good health and longevity. Though mentioned in The VOICE on prior occasions, investigators at the CHR are getting increasingly fascinated by this subject and therefore convinced the editorial team of The VOICE to give this subject more recognition in the pages of this month’s issue.

Another important subject addressed in this issue is whether better IVF outcomes are really in the best interest of IVF clinics. After all, a majority of failed cycles are followed by another cycle and, therefore, additional revenue. In contrast, a successful IVF cycle leading to pregnancy, assuming it is not miscarried, shortly thereafter terminates income for the clinic until another pregnancy is desired (if ever).

Finally, in a short article, we also reemphasize the importance of a comprehensive infertility evaluation for every newly presenting couple. We are often surprised at how little testing was done on a female/couple before the start of the IVF cycle. The CHR always strongly believed that a detailed history and laboratory testing in almost all cases would allow for a presumed diagnosis. Like with any other disease, first comes the diagnosis, which then can be followed by a treatment recommendation. How treatments can be decided considering the frequent poly-causality of infertility has always been somewhat astonishing to us. Understanding causality would appear to us like a rather universal prerequisite for newly presenting couples.

This will do for the month of October. Just a quick reminder that on December 1- 3, 2023, the FRMC (Foundation for Reproductive Medicine Conference) will again be organized in collaboration with the CHR in NYC. We would love to see as many of you as possible at the conference. This is the first time after a 3-year break due to COVID. Again, we were able to recruit an amazing faculty of world leaders in their respective fields. As always, the conference offers day passes at greatly reduced rates to students, residents, fellows, and infertility patients (whether the CHR’s or from other clinics). For further details, please see the program on pages 6-10.

OCTOBER 2023 The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 3

The Editorial Staff of The CHR VOICE

4 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice ADVERTISEMENT

TRYING TO REACH THE INFERTILITY COMMUNITY?

Have you thought about advertising in the VOICE?

This newsletter every month goes electronically to ca. 80,000 infertility patients, medical professionals in the field, and members of the media, with over 25% (an unusually high number) also opening the VOICE.

For further information, please contact: Ms. Alexandra Rata (212) 994-4400 or e-mail to arata@thechr.com

ADVERTISEMENT 12 | s E p TE m BER 2023 | The Voice The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 5 ADVERTISEMENT

Scan the QR code to watch the FMRC 2023 introduction video!

ADVERTISEMENT 6 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice

Continued from page 6 ADVERTISEMENT The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 7

Continued from page 7 ADVERTISEMENT 8 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice

Continued from page 8 ADVERTISEMENT The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 9

Continued from page 9 ADVERTISEMENT 10 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice

Does female and male fertility reflect upon a healthy life, as well as longevity?

Older evolutionary theories of aging predicted that increased life spans would come at the cost of reduced fertility.1 However, exactly the opposite conclusion appears also logical: Since it is in an evolutionary paradigm, reproductive success leads all biological activities in importance, reproductive success and therefore, fertility/fecundity, must be closely intertwined with good health and longevity. Reversing this paradigm, infertility could also be expected to offer a prospective assessment of disease risks and potentially shortened lifespans.

However, some later studies were unable to confirm these older evolutionary theories. For example, in 2011 when Dutch investigators studied suspected associations of female fertility with age at menarche, menopause, and mortality in 3,575 married women, they failed to demonstrate associations between fertility and age at menarche and menopause but was inversely associated with mortality: Those with 2-3 children had significantly lower mortality than women with no children, though this survival advantage disappeared with larger numbers of children.2

Other studies were more supportive of the older evolutionary theories: A more recent Chinese study of 1,623 older adults on the other hand reported a (marginal – p<0.05) correlation between mortality and larger numbers of children.3 Moreover mortality trended upwards with more male offspring and showed a declining trend with more female births. A study of European populations also found a strong adverse effect of large offspring numbers on longevity.4

It has been suggested that aging may be the consequence of an accumulation of mutations, leading to tissue dysfunction, a notion supported by the findings of a recent study performed in Utah that

demonstrated age-adjusted mutation rates, indeed, associated with higher all-cause mortality in both sexes combined. Those in the top quartile of mutations demonstrated more than double the mortality of those in the lowest quartile (p=0.008), with the medial survival difference being 4.7 years. When it came to fertility, women with higher mutation rates demonstrated significantly lower birth rates and a younger age at first birth. The authors concluded that germ lime mutation rates offer a measure of reproductive as well as systemic aging.5

Two articles in a special issue of Fertility & Sterility recently offered somewhat superficial reviews on the subject in females6 and males.7 That associations between factors relating to reproduction and general health have become a very “chic” new subject of scientific exploration, was recently also demonstrated by a paper in The Journal of the American Heart Association which reported

Continued on page 12

The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 11

“Reversing this paradigm, infertility could also be expected to offer a prospective assessment of disease risks and potentially shortened lifespans.”

Continued from page 11

an apparently causal role of several reproductive health factors on cardiovascular disease.8 Specifically, earlier age at first birth increased the odds of coronary heart disease (p=3.72x10-7), heart failure (p=0.009), and marginally for stroke (p=0.048). A higher number of births increased the risk of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, ischemic stroke, and stroke. Earlier menarche increased the risk of coronary heart disease (p=1.68x10-6) and heart failure (p=5.06x10-7), - all pretty remarkable findings.

Assuming that these associations are reversible, one could propose a thought experiment along the following lines: If high fertility shortens life spans, do circumstances that prolong life spans adversely affect fertility/fecundity? An interesting example to investigate within such a context would, for example, be the new weight-loss drugs, like Vegovy, Ozempic, or Munjaro. This family of drugs is now being investigated for additional benefits, including positive effects on cardiovascular diseases in women and men and, possibly, longevity. Under the assumption of reversibility of associations, these drugs then should adversely affect fertility/fecundity. Then again, who would be surprised if the new “wonder drugs” also would improve fertility/fecundity? After all, obesity is in both sexes clearly associated with infertility.

REFERENCES

1. Kirkwood TBL. Nature 1977; 270:301-304

2. Kuningas et al. Age (Dord) 2011; 33(4):615-622

3. Zhou et al. BMC Public Health 2022; 22:682

4. Hsu et al. PLoS One 2021; 16(8):e0255528

5. Cawthon et al. Sci Rep 2020; 10(1):1001

6. Huttler et al. Fertil Steril 2023; 120(3):421-428

7. Belladelli et al. Fertil Steril 2023; 120(3):429-437

8. Ardissino et al. Am J Heart Assoc 2023; 12(5):e027933

12 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice ADVERTISEMENT

MY A OF

PIECE MIND

Private medicine - at its end or at a new beginning?

By Norbert Gleicher, MD Founder, Medical Director, and Chief Scientist The CHR, New York, NY

Some history to start with

That private medicine in the U.S. has radically changed over the last decade by now must be obvious. Major changes started in the late 1990s, when Wall Street for the first time concluded that medical care, then mostly provided through small mom-and-pop practices, was inefficient and, therefore, a huge potential financial opportunity for investors. The frequently heard analogy at the time was the evolution from mom-and-pop grocery stores to local, or even multi-state, supermarket chains.

Investors started buying up mom-and-pop practices (and small group-practices) in various medical specialties in attempts to establish dominant nationwide chains of provider practices, literally within months producing several chains with billion-dollar Wall Street valuations. The underlying assumptions were that such national clinic chains would benefit from the usual advantages of size in the availability of financial resources for growth, purchasing power, and

Continued on page 14

The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 13

overall cost control. Such clinic chains were also assumed to quicken the pace toward unified best practices and, therefore, improve the quality of medical care by producing improved outcomes.

Even though most U.S. states at that time prohibited the practice of medicine by medical corporations not owned by physicians (laws to these days still in place in most states), corporate lawyers quickly developed legally valid ways to circumvent these laws, which allowed investor-owned medical practice chains to exert virtually full administrative as well as medical control over those companies.

Unsurprisingly, hospitals started feeling threatened in their referral patterns and, consequently, started competing for medical practices, thereby raising already excessive acquisition costs. These competing efforts clearly accelerated the decline in physician-owned private practices all over the country, based on data from the American Medical Association (AMA), by 2016 resulting in a majority of private practices no longer being owned by physicians. Only 47.1% of physicians by that point were still practice owners, the same percentage was employed by a medical practice without ownership, and 5.9% worked as independent contractors.1 As of 2023, almost three-quarters of physicians in the U.S. are salaried employees, and at least half of all physician practices are owned by hospital or investor-owned corporate entities.2

During those early stages of private practice consolidation in the 1990s, hospitals, in the end, were actually more successful in integrating acquired practices because the first wave of large billion-dollar national clinical practice networks in all specialties imploded in the late 1990s even quicker than they were initially put together in what Wall Street later came to call the “physician practice management bubble.” Well summarized by Becker’s Healthcare Website, 3 in 1998, two major physician practice management companies (PPMCs), as these practice networks were then described, in different specialty areas reported disappointing earnings and shortly thereafter declared bankruptcy. By 2002, eight of the 10 largest PPMs had declared bankruptcy

and the figure below best summarizes the complete obliteration of the combined market cap of publicly traded PPMCs during literally only a few short months, obliterating billions of dollars in investments.3

With some personal history added

Then still living and working full-time in Chicago, I was heading the CHR, at the time the largest provider of fertility services in the city by far and, likely, the second- or third-largest IVF provider in the nation. Considering what was happening in other fields of medicine, it was not surprising that the CHR attracted the attention of Wall Street and was aggressively pursued by several prominent Wall Street firms, which saw the CHR, as a key anchor practice for a dominant nationwide PPMC in the infertility field. Though initially hesitant, Wall Street, ultimately convinced us that we should not pass on this opportunity for the CHR, which at that time was owned by over 10 physician-partners and provided fertility services in eight locations throughout the larger Chicagoland area, performing over 2,000 IVF cycles annually, - in those days considered a huge number.

Among several Wall Street firms that had pursued the CHR, we chose Smith Barney as the primary Wall Street sponsor to help in establishing a PPMC and take it public, which was likely the leading Wall Street firm in this market niche at the time. Simply based on the announcement that Smith Barney was sponsoring the CHR, a large local insurance company and a PPMC in another medical specialty area invested several million dollars into the newly formed infertility PPMC which, as of that point, only was represented by the CHR. Funds from those investments were then used over the following year to purchase five additional fertility clinics around the country and to establish a brand new practice in NYC. With a public offering planned within months, Smith Barney strongly felt that the new company had to have a presence in NYC. Because the city at that time did not offer suitable IVF clinics for purchase, a decision was reached to start a brand new CHR-New York (the forerunner of today’s CHR).

Continued from page 13 14 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice

Figure 1

As the word got out that Chicago’s CHR was planning on coming to NYC, I was contacted by colleagues from the local Mount Sinai as well as Columbia University fertility programs both experiencing a strong need to move out of their own hospital facilities for their own very special reasons at that time, but not having the necessary financial resources to do so. A collaborative effort with the CHR offered an attractive opportunity. Similarly, for the CHR, the opportunity to work with well-established colleagues in the city from two prestigious academic institutions, of course, represented a unique opportunity to enter the NYC marketplace with considerable immediate visibility and credibility.

There was only one problem: New York medical institutions were not (and to this day are not) known for their collaborative spirits and neither our Columbia nor our Mount Sinai colleagues were very excited about the possibility of not having exclusivity in the relationship with the CHR. Considering my personal experience with academic institutions (which included a fellowship, residency, and two years of full-time faculty membership at Mount Sinai), I strongly felt that the new PPMC in a market as large as NYC should not only become identified with, and dependent on, only one academic institution and, ultimately, indeed, succeeded in convincing both academic institutions that such a solution was also in their best interests.

After contracts were signed, the PPMC rented a large space in mid-town on Madison Avenue and initiated a multimillion-dollar buildout, large enough to accommodate the fertility programs of both institutions. Roughly halfway through construction, rumors started swirling around NYC that Mount Sinai and NYU might merge. Though the CEO of Mount Sinai at the time assured us that such a merger was not as close as suggested in the media and, even if it were to happen, would not affect the agreement, only roughly two weeks later, Mount Sinai informed us that, because of the imminent merger with NYU (which really never happened), Mount Sinai was withdrawing from the agreement and merging instead with the NYU IVF program (which also never happened). Pointing out the previously signed contract, we were advised, that the contract mandated approval by Mount Sinai’s Board of Directors which had not yet met. Mount Sinai considered the contract null and void.

Because of the by then already scheduled public offering of the new PPMC’s shares through Smith Barney and two other Wall Street sponsors, we were advised against pursuing the matter further, with the consequence being that the PPMC found itself exactly in the position we had attempted to avoid, - being identified with, and dependent on, only one academic program. Almost as expected, the arrangement between the PPMC and the Columbia group only survived for barely one year, resulting in yours truly over a period of almost three years having to assume responsibility for the management of centers in Chicago and NYC and, therefore,

weekly splitting time between these two cities. This craziness only ended in 2002, when I finally relocated full-time to NYC after selling the Chicago operations to a local colleague.

Most current observers are unaware that many of the changes we have been observing over the last decade, practically are reruns of the 1990s. Witnessing over the recent decade the resurgence of PPMCs in all medical specialties, including infertility, it became quickly apparent that investors in this second wave of investments in the private practice of medicine learned important lessons from mistakes made in the first round, allowing the quick evolution of seemingly highly successful and very valuable PPMCs of a much larger scale than even the initially most successful PPMCs in the 1990s achieved. At the same time, I would argue that, despite having been more successful than in the first round, current generations of PPMCs and of private practice clinic networks owned by hospital organizations have started to show similar stress symptoms as observed in the late stages of the first PPMC bubble in the 1990s.

Why the bubble burst?

In 1998 we started a roadshow with Smith Barney with a pre-offering valuation of the newly formed infertility PPMC of US$ 110 million (in those days a very high valuation for a start-up). On the second day of the roadshow, the offering was completely sold out and Smith Barney was planning on raising the offering price per share. On that same evening, both the above-noted large PPMCs, however, reported disappointing earnings and we had to interrupt the roadshow. Though Smith Barney had anticipated a quick recovery of the sector and expected a return to a public offering within months, this, of course, never happened and, the whole sector, as the figure above so well demonstrates, basically disappeared (as, apropos, did Smith Barney as well, - a few years later).

Our PPMC still struggled for almost a year but, finally, shut down after selling the individual clinics back to their prior owners. Since the NYC clinic had no prior owner, I purchased it, determined to apply the lessons I learned over the preceding years. Today’s CHR is, therefore, the product of this process, at least to a degree explaining why the CHR, as a fertility center, is so distinctively different from most other providers of fertility services.

But before we get to that, a few reasons why PPMCs failed the first time around: Bill Frack and Nurry Hong in a succinct 2014 postmortem suggested that those failures occurred because the concept at that time “was premature and poorly executed – but not unsound (in its underlying hypotheses) …. and has now a clear strategic rationale and value proposition,” 3 implying that both of those were not existing in the 1990s. Though I agree with their overall conclusion that, for several reasons, the concept may have been premature and was executed poorly, I can agree with this

The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 15 Continued on page 16

conclusion only with some further caveats: In my opinion the most important is that investors, still to these days, overestimate the ability of PPMCs to “fill fundamental gaps in the capabilities of traditional physician offices.”3 They, indeed, do have much better abilities to make required capital investments, create data-sharing infrastructures, and achieve administrative efficiency. They also unquestionably have better abilities to acquire new patients, negotiate sophisticated risk-sharing agreements, and drive health care costs lower. But, whether all of these abilities in the end, as promised, improve the quality of health care, in my opinion, is highly questionable.

As we will further discuss below, rapidly evolving evidence suggests the opposite: these developments appear to adversely affect the quality of medical care and, in addition, actually appear to increase costs. Also, based on my experience in managing what likely represented the first (small) clinic network acquired in the fertility field, this is for the following four reasons not surprising: (i) Purchasing physicians’ medical practices, even in the presence of strong financial incentives, instantly significantly reduces their productivity. (ii) Even more importantly, the process adversely affects their creativity (on which past successes of the practice were often based). (iii) The quality of cost-effectiveness evaluations for new capital expenditures declines, and the (iv) introduction of best practice innovations can be equated to “herding cats” and, considering the prevalent natural individualism of medical practice, in general, is either an almost impossible task or if imposed, leads in the long run to an increasingly toxic practice environment between clinic and administration.

As a consequence, profitability expectations are routinely missed, setting into motion “more drastic administrative managerial interventions,” often highly unpopular with the clinical staff and, therefore unsurprisingly, also quickly perceived by patients. What once was a thriving private practice setup, therefore, quickly turned into a “clinic-like” setup, with very different patient expectations. As patient expectations change, the patient population the practice serves changes in parallel, with the important fraction of self-pay patients for every fertility clinic declining and, with it, profit margins narrowing.

Here is a personal example of what happens: Being myopic (nearsighted), I require regular vision checks, for over a decade until recently received from a very personable ophthalmologist in a small and crowded office, - though, despite substantial use of technical support staff, always characterized by an opportunity to interphase with the physician. One day, he unfortunately moved out of the city and sold his practice to an ophthalmologic PPMC. “Wanting to introduce himself to a colleague,” I met the new physician on my first subsequent visit only for a brief handshake. On my second visit a few months later, I saw only staff and decided to switch to a new ophthalmology office.

Because it is only within walking distance from the CHR, I again chose an office owned by a (different) PPMC. During my

first visit, I met a very personable but obviously rushed ophthalmologist who, as a colleague, apologized for “how long she had left me waiting in the exam room.” Returning a little over six months later in response to a routine reminder notice from the office, I was left abandoned in the waiting room for over 45 minutes, even though I, on purpose, had made an early morning appointment before my own office hours started. I finally walked out (without examination), with the reception clerk for the first time noticing me and profusely apologizing for “the office being short on staff.” I am now, of course, again searching for a new ophthalmology practice; this time it will, however, not be a PPMC-owned practice if such a possibility still exists these days in Manhattan!

What all of this means for medicine in general Estimates suggest that, following practice acquisitions in a $ 2 billion acquisition spree in 1997, in 1998, 39 public and 125 still private PPMCs (like ours) existed in the U.S.,3 not counting practice networks created by hospital systems. How could such a seemingly attractive and successful industry then, literally, vanish within months?

The answer is, likely, not as simple as suggested by the principal explanation proposed in the literature: Significant overpayment for physician practices, especially large enough physician groups that were most interesting for investors is indisputable as a contributing factor. These groups were often purchased at 50100% above cash flow basis. But, there were also other important causes why expected profit margins were routinely missed by surprisingly large margins: PPMCs, for example, were hardly ever able to bend anticipated cost curves. Prediction models, built on growth in especially IVF cycle utilization, often also did not pan out. Not only was growth not as rapid as anticipated but, even more importantly, increasing insurance coverage for IVF services, widely anticipated to significantly contribute to cycle number increases, did so much slower than anticipated (insurance companies restricted IVF access, often mandating other treatment modalities before authorizing the use of IVF). Also not anticipated in many forecasts were the effects of increasing insurance coverage for IVF on cycle reimbursement rates. The reimbursement insurance companies were willing to pay, of course, did not even come close to what private market rates had been, further exacerbating the observed deficits from projections.

However, the likely and ultimate reason for the failure of the first wave of PPMCs was a rapidly growing level of dissatisfaction of the medical staff involved. They were not only frustrated by poor management but also by the loss of alleged value of the newly established PPMCs. Because many of the medical practice purchases included equity participation in the PPMC that acquired their practices, physicians saw the value of the sale prices for their practices declining and, ultimately collapsing.3

Though PPMCs in the current second wave claim to have a much clearer strategic rationale and value proposition, I am

16 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice

Continued from page 15

not convinced that this is really the case. To me, it still appears that practice acquisition values are often highly exaggerated and that does not only apply to billion-dollar acquisitions of whole networks in the fertility field as we have witnessed (more about that below), but also to million-dollar acquisitions of group-practices, once again often partially paid with equity participation and, therefore, depending on continuous improvement in practice values if sellers are to remain satisfied.

However, the largest danger in my opinion comes from societal dissatisfaction with the trend toward a reorganization of private practice away from physician-owned toward investor-owned practices, which is based on the perception that this is just another profit-motive-driven idea of Wall Street, leading to poorer quality medicine and higher costs.2,4,-6 The field of infertility also must confront the inherent economic conflict represented by the fact that failure to achieve pregnancy in an IVF cycle, more often than not, leads to another IVF cycle (and, therefore, additional revenue for the clinic), while success in establishing pregnancy, assuming no miscarriage occurs, ends the current relationship with the patient (and, therefore, ends all revenue-generation). To a degree, economic incentives in IVF are unnaturally stacked against success.

What all of this means for infertility practice

All of this has major additional significance for the fertility field, where PPMCs are already in possession of a highly significant and ever-growing share of the national market.7 This newsletter in the literature review section routinely offers updates on new acquisitions and sales of individual clinics and/or clinic networks. The most remarkable has been the recent sale of the international IVIRMA network at an amazing enterprise value that exceeded US$ 4 billion.

Our Spanish colleagues who built this empire must be congratulated on an unprecedented business achievement. When first rumors started circulating that IVIRMA was seeking a buyer at a valuation exceeding US$ 1 billion, nobody (except, of course, the company’s ownership) considered this a serious proposition. Barely a year later, the purchase price had quadrupled. Considering standard business models followed by equity investors which expect a highly profitable resale of purchased companies within 3-7 years, one must wonder not only about the overall feasibility of such a venture in the infertility arena, but also about the impact that such a time-restricted, aggressively profit-driven business plan may have on how, and at what cost, such a business model will be pursued by IVIRMA and other similarly-large IVF clinic chains.

One must assume that a hard-driving management structure that, considering existing time pressure, must maximize profitability, will have to drive down the cost structure of the company that offers fertility services to patients and, at the same time, must increase the revenue generated by the company. That billion-dollar acquisitions in health care, consequently, can threaten equitable access to such health care, raise cost, and

reduce the clinical autonomy of physicians has, therefore, raised serious concerns.8

In fertility practice, several years ago we already pointed out the close association with declining live birth rates all over the world because of the increases in numbers and utilization of mostly unvalidated and often even harmful (to outcomes) “add-ons” to IVF practice.9 One, of course, must wonder about potential motivations!

Indicating the dependence of current IVF practice on “addons,” a Wall Street analyst who interviewed me over a year ago, claimed that an analysis he did suggested that roughly a third of U.S. IVF clinics would have to shut down or otherwise reorganize if they lost current PGT-A revenues, as they reflect most of those clinics’ profit margins. Considering low IVF insurance reimbursements and the fact that PGT-A fees (which insurance companies uniformly do not cover) are direct cash payments from patients to IVF clinics, those payments have become crucially important contributions to average cycle revenue for many clinics. Who then can be surprised about increasing PGT-A utilization in the U.S. despite increasing evidence that PGT-A does not improve IVF outcomes in general populations and, in many women, actually reduces pregnancy chance? We, moreover, in an abstract that was accepted at the annual 2023 ASRM meeting in New Orleans and submitted for publication as a full-length paper,10 demonstrated based on a national U.S. data set of reporting IVF clinics that the highest PGT-A utilizing clinics (80-100% of cycles utilized PGT-A) had significantly higher equity and venture capital ownership than lowest utilizing clinics (0-20% utilization). These data suggest the possibility that financier-owned clinics in efforts to raise revenue, consciously or unconsciously favor the utilization of useless “add-ons.”

Conclusions for the CHR

This brings us back to the basic question of this column of whether we are witnessing the end of private medicine or a new beginning. Observing the evolution of several different healthcare systems around the world, my strong suspicion as of this moment is that we in the U.S., indeed, are witnessing the evolution of a new private practice model, which in the infertility field will be bifurcated: a majority of patients will, indeed, receive their treatments in multiple-provider clinic setups through highly regulated and protocol-driven PPMCs and contracted hospital provider networks, while only a small percentage of private practice care (my estimate is ca. 15-20%) will continue to be provided at higher costs in a more traditional model of private practice, characterized by a more personalized physician-patient relationship.

In some specialties, it will be in the format of what nowadays in the U.S. is called “concierge medicine;” in some European countries insurance companies already offer similar services under “supplemental insurance plans” which can be purchased as additions to standard private essential insurance coverage.

The V oice | s E p T m EBER 2023 | 9

on page 10

Continued

The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 17 Continued on page 18

In the infertility field, I expect the bifurcation to be not only service-oriented but, based on the recognition that high-volume and low-cost fertility clinics are simply incapable of offering at current reimbursement levels satisfactory services to poor prognosis patients, also qualitative. In other words, I predict that the current discrimination of poor prognosis patients by the medical insurance industry (by, for example, age restrictions for coverage, limitations of cycle attempts, etc.) will expand in parallel to improvements in the general infertility coverage for good- and average-prognosis patients, - not dissimilar to the coverage of IVF services in Scandinavian countries, where IVF services are widely available under government-managed health insurance plans, but cut off at age 40 to 42.

In the early 2000s, the decision that the CHR, going forward, would strive to develop special expertise in managing the “aging ovaries,” we also soon recognized that the medical efforts required to serve a primarily poorer-prognosis patient population would significantly exceed what was required for more standard patients. The CHR at that point saw no other option but to terminate a majority of insurance contracts the center had signed on to before, and also had to reject joining the New York State Program that covered IVF services, as none of these insurance contracts were even close to reimbursement rates the CHR required to reach break-even.

One does not have to hold an MBA degree to understand that caring for much older than average infertile women who have already failed multiple IVF cycles, often at multiple clinics, mandates more involved, personalized, and individualized treatment efforts than are required for on-average, much younger infertility patients, often undergoing their first IVF cycles. The CHR, consequently, has consciously avoided the “clinic atmosphere” that has evolved in many other IVF clinics, especially with the rebirth of PPMCs and hospital-owned provider networks.

By no means meant as a criticism of these clinics, these clinics serve an important function as providers of fertility services for a majority of usually younger and uncomplicated infertile women. Like other fields in medicine, infertility has been evolving, - in the process converting much of what was difficult in the early days of IVF into clinical routine, fully and conveniently accessible to patients in their local neighborhoods at basically the same quality and with similar outcomes as in “famous” IVF centers to which infertility patients in early days of IVF often had to travel over significant distances. By reaching the decision 20 years ago to concentrate on poorer-prognosis patients, the CHR also recognized that these women often would not receive the best care in their neighborhood’s routine IVF clinics, and, therefore, would have to continue to travel to more “specialized” IVF centers (like the CHR).

We feel that the earlier discussed changes in medical practice, and especially in how infertility care is provided, confirm the evolution of a bifurcated fertility field, as we envisioned 20 years ago. We, however, are surprised that this bifurcation apparently

has not yet been recognized by Wall Street and other investors in the fertility field. Consequently, business models to this day appear flawed because they ignore the “most expensive” 15% of infertile women, - poorer prognosis patients. Older women, moreover, represent the age group in which the utilization of IVF is increasing more rapidly than at any other age. One would think that this kind of information would be of interest to investors and insurance companies.

As things stand, poorer prognosis patients are not identified early in their infertility journeys. Therefore, they often unnecessarily fail multiple IVF cycles in such patients’ unqualified IVF clinics. Not only is this emotionally painful and often costly for these patients but those efforts also, often, represent wasted valuable time for patients who can least afford time wasted. Particularly insurance companies should be interested in identifying these patients early because, once pregnant, they, because of unusually high obstetrical complication rates, also represent excessive obstetrical and perinatal costs.

REFERENCES

1. Murphy B. AMA, https://www.ama-assn.org/about/research/ first-time-physician-practice-owners-are-not-majority#:~:text=Ac cording%20to%20data%20drawn%20from,been%20evident%20in%20 recent%20years

2. Zhu et al. N Engl J Med 2023; 389(11):965-968

3. Frack B, Hong N. LEK Consulting. https://www.beckershospitalre view.com/hospital-physician-relationships/physician-practice-manage ment-a-new-chapter.html?oly_enc_id=1505B4491778G9P

4. Borsa et al. BMJ 2023; 382:e075244

5. Goozner M. BMJ 2023; 382:p1396

6. Rotenstein et al. JAMA Health Forum 2023; 4(3):e230299

7. Patrizio et al. J Assist Reprod Genet 2022; 39(2):305-313

8. Shah et al. N Engl J Med 2023; 388(2):99-101

9. Gleicher et al. Hum Reprod Open 2019; 2019(3):hoz017

10. Patrizio et al. Abstract accepted to ASRM 2023 and submitted for publication.

18 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice

Continued from page 17

ADVERTISEMENT

CYCLE START IS NOT ANY LESS IMPORTANT THAN THE CYCLE ITSELF

Understandably, everybody is often in a rush to get IVF cycles started: patients are anxious and IVF clinics’ cycles are the principal revenue generator. But many – if not most – IVF cycles require preparation. What we mean by this is that as last-resort fertility treatments, IVF cycles are emotionally more draining than other fertility treatments, very costly (especially without insurance coverage), time-consuming for patients, and highly complex for fertility service providers. The latter point is especially relevant for those fertility clinics that seriously attempt to individualize cycle protocols, as has been a routine practice at the CHR for almost 20 years.

Many, if not most IVF clinics unfortunately still routinely utilize only one or two standard IVF protocols and even this small number of protocols defines an IVF cycle as a complex process, even though the complexity greatly increases with increasing numbers of potential cycle protocols. Moreover, complexities increase even further with the likelihood that an initially selected protocol may change in the middle of a cycle because of unanticipated observations. As utilizers of highly individualized IVF protocols, we are emphasizing the difference between using only a few standard protocols and true individualization of protocols because the latter is only possible if infertile couples are extremely well “understood” in their often-multifactorial pathology that underlies their infertility. Such an understanding can only be obtained through a very detailed history and laboratory investigation at the intake of new patients into a fertility program.

Such a detailed historical evaluation of new patients at presentation is only a first step in ultimately being able to define the “best” IVF cycle protocol. The patients’ histories then dictate their diagnostic testing process and these two steps in preparing them for their “best” treatment protocol are mutually dependent on each other: A better history will lead to a more thorough diagnostic work-up and vice-versa.

Recognizing that infertility, much more often than not, will be multifactorial (with one or more than one cause in females and males), it is not only of crucial importance to diagnose all possible contributions to a couple’s infertility, but it is maybe even more important to treat all of these contributing causes concomitantly. Just missing one, may invalidate all other treatments, - even if administered perfectly. This is where, at times,

patience is required from patients as well as the treating physician because not all treatments follow the same time schedule.

One of the more crucial steps in preparing many infertile women for an IVF cycle is attempting to improve ovarian performance. Please note that we are attempting to improve ovarian performance and not ovarian reserve! The difference between these two concepts is important because ovarian reserve, defined as the number of remaining follicles/oocytes in a woman’s ovaries, very likely cannot be improved with current therapeutic abilities. Ovarian performance, or what we years ago started calling the “functional ovarian reserve (FOR),” defined as the small growing follicle pool immediately after follicle recruitment between primary follicle and small antral follicle stages, on the other hand, can be improved in many infertile women, but such improvements take time – at least six to eight weeks. The reason is that small growing follicles between primary and small antral stages still require at least six to eight weeks of further growth and maturation before they reach the so-called gonadotropin-dependent stage (i.e., where they become dependent for further development on the gonadotropin hormones routinely used in IVF cycle stimulations).

CONFLICT STATEMENT

The CHR and some of its staff members own shares in a company (Fertility Nutraceuticals, LLC, doing business under the name Ovaterra), which produces a DHEA product. Since the following paragraphs address androgen supplementation with DHEA, readers of this paragraph are advised that opinions expressed in this paragraph may be biased by financial interests.

We often explain these treatments of ovaries with a car analogy: If a car engine does not function well anymore and we do not want to replace it, we usually “clean it out,” trying to make it perform at its best, while fully recognizing that a new engine would do better. The same principle applies here: As we cannot yet “make new eggs,” we are doing the next best thing, - we are trying to make our patients’ ovaries work better, fully appreciating that young donor eggs, of course, would do better.

WHAT HAPPENS BEFORE IVF

The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 19 Continued on page 20

In principle, this is done in two ways: If infertile women have low androgen levels (male hormones, with the most important one being testosterone), we supplement with androgens, in most cases with a hormone called dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), from which our bodies make testosterone.1 If insulin growth factor -1 (IGF-) is low, we supplement with human growth hormone (HGH) because HGH stimulates the production of IGF-1.2

Both of these treatments make only sense if either androgens or IGF-1 levels are low. Androgens as well as IGF-1 decline with age. Androgens especially may also be low in some younger women. Ovaries, however, require both of these substances at normal levels if the “engine” is to work at its best because both support the hormone FSH during small growing follicle stages in making follicles grow and mature. Once they have done their job, the so-affected follicles still need six to eight weeks to reach gonadotropin dependency. Consequently, if patients with low androgens and/or IGF-1 are properly prepared for IVF, they must be on supplementation for at least six to eight weeks before IVF cycle start.

However, this is not the only preparation that may take time before an IVF cycle is initiated. Another very important point is the integrity of the uterine cavity. Replacing embryos into an abnormal endometrial cavity makes little sense. Therefore, every endometrial cavity should be explored before IVF, at least through a hystero-sonogram. If this test does not offer reassurance that the cavity is normal, the test must be followed up by an MRI of the uterus and/or a diagnostic hysteroscopy. If a pathology is found, it in most cases should be removed. Such pathologies may be scar tissue in the cavity, endometrial polyps, or

into the cavity protruding fibroid tumors (so-called submucous myomas).

Whether surgery should be performed or not, is not always an easy decision. If it involves minor interventions, as with mild adhesions or with small polyps, surgery is usually indicated before initiations of IVF cycles because such minor surgeries usually do not delay an IVF cycle by much. The situation can be very different if a myomectomy (surgical removal of a fibroid) appears indicated. Such a procedure can delay an IVF cycle often by at least three to four months, which especially in older patients may have a significant impact on pregnancy chances.

This brings us to the last point this communication wants to make: Ultimately, an IVF cycle should never be started without, first, having an in-depth discussion with the involved patients. In the CHR’s opinion decisions that are either black or white are relatively rare in medicine. Most decisions reflect varying gray tones. Involvement of well-informed patients in the decision-making process, therefore, at the CHR is considered essential. As we always explain to our patients: “We are not qualified at all to tell our patients how to live their lives. We, however, are very well qualified to advise them what their options are (with risks and benefits). In the end, the choice must always be theirs!”

REFERENCES

1. Gleicher N., BJOG 2016;123(7):1106

2. Gleicher et al., J Assist Reprod Genet 2022;39(2):409-416

3. Gleicher et al., Hum Reprod 2013;28(4):1084-1091 ADVERTISEMENT

20 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice Continued from page 19

& INFANT LOSS

AWARENESS MONTH

a few words about miscarriage risk, including a new “Case Report Of The Month”

Pregnancy and Infant-loss Awareness Month reminds us how prone mankind is to pregnancy loss: roughly onethird of implanting embryos are miscarried so early that these miscarriages are called “chemical pregnancies.” That such early pregnancy losses existed was not even recognized until IVF came on the scene a little over 40 years ago because no one obtained early enough blood tests to test for pregnancy in those days. If menstruation was delayed by a few days, this was usually attributed to physiological irregularities in menstrual patterns. These pregnancies are called “chemical” because they are only diagnosed by chemical means via a pregnancy test and are not yet visible by ultrasound.

Another third of pregnancies experience spontaneous miscarriages after clinical diagnosis by ultrasound at approximately 5.5 gestational weeks (3.5 weeks post-implantation) when a gestational sac with a fetal pole and fetal heart can be visualized with good ultrasound equipment.

What these statistics demonstrate is the extreme inefficiency of human reproduction, resulting in the loss of approximately two-thirds of all embryos that are already implanted. In addition, only a relatively small minority of embryos available for implantation do so, further aggravating this inefficiency.

Considering this sparsity of successful pregnancy from an evolutionary standpoint, it must offer significant benefit for the survival of our species to have been retained by evolution over so many thousands of years. What this likely benefits seems to be very obvious in this case: a high loss rate of embryos and already established pregnancies very obviously protects our species from much larger numbers of abnormal births than we currently experience.

In practical terms, this means that we may not want “to fight” a large majority of pregnancy losses and, indeed, may not view them as “adverse” events, but, rather, consider them as an integral part of one of nature’s evolutionary ground rules, - “survival of the fittest.”

This is an important message that is not always well understood by the public and should be appropriately reemphasized this month. However, at the same time, this is also a message that does not apply to all pregnancy losses. A

minority of pregnancy losses happen to what are considered normal pregnancies, with the term “normal” used to describe pregnancies that are chromosomal-normal and do not demonstrate obvious congenital morphologic abnormalities. It does not describe a truly fully “normal” pregnancy because truly “normal” pregnancies will not get lost.

A better way to make this point is probably to differentiate pregnancy losses based on whether they are caused by, the fetus or the mother. For the fetus being the responsible party, either the egg, embryo, and/or fetus must demonstrate abnormalities. If that is not the case, one can assume that the reason for the pregnancy loss must be the mother’s. It is of utmost importance that this differentiation is made correctly.

The reason why this differentiation is of such significant importance brings us back to the fact that fetal abnormalities, with very rare exceptions, are random events (i.e., bad luck) and, therefore, do not indicate recurrence risks. They rarely demand treatments. Maternal causes of pregnancy losses often lend themselves to treatments and must be pursued to try to avoid repeat losses. That usually means that affected women must undergo appropriate diagnostic testing, followed by treatment.

Maternal causes of losses encompass a wide variety of possibilities and one, therefore, faces the question of when such diagnostic workups should be initiated. Medical textbooks to this day suggest that they should not be pursued until a woman has experienced three consecutive pregnancy losses. The CHR does not subscribe to this opinion and believes that it causes unnecessarily preventable pregnancy losses. We here at the CHR do not believe that there exists one miracle number of prior miscarriages that, automatically, defines who should be tested. Instead, the CHR pursues (as in almost all of its clinical decisions) an individualized approach, in this case, based on a patient’s detailed past medical and family histories.

Here is our “CASE REPORT OF THE MONTH” as a good example: A 32-year-old woman came to the CHR because she had not conceived in over a year after experiencing a prior spontaneous pregnancy that unfortunately had been miscarried at 10 weeks gestational age, a fetal heart was seen on ultrasound in an apparently normal singleton

IN RECOGNITION OF

PREGNANCY

Continued on page 18 The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 21 Continued on page 22

Continued from page 17 pregnancy several weeks after. The only unusual finding noted in the ultrasound report at the time was a small (and asymptomatic) subchorionic hematoma.

Discussion: This patient presented to the CHR at a relatively young age because of so-called “secondary” infertility of over one-year duration (this diagnosis is reached if infertility sets in after at least one prior pregnancy). It is important that she did not present because of concerns about her earlier miscarriage, even though that miscarriage occurred relatively late (at 10 weeks and after a positive fetal heart) and was accompanied by a subchorionic hematoma by ultrasound. We will return to why these two findings are of importance. Her past medical history was otherwise negative, - except that her medical chart reflected a maternal history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), - an autoimmune disease.

The female and her partner underwent a routine diagnostic infertility workup at the CHR. Based on mildly high FSH (10.8 miU/mL) and mildly low AMH (0.8ng/mL) for her age, the female was diagnosed with premature ovarian aging (POA). She, in addition, demonstrated a mildly positive ANA of homogenous and speckled type at a titer of 1:160 (a relatively low level).

In summary, the patient was a young woman with secondary infertility, POA, and with evidence of a hyper-active immune system based on a positive ANA and a maternal family history of SLE (autoimmunity is highly familial). She, in addition, in her prior miscarriage demonstrated a subchorionic hematoma, which is a finding associated with the presence of autoimmunity (especially ANA and antiphospholipid antibodies) as well as increased miscarriage risk. 1,2

Suddenly, this patient who initially presented as an infertility patient, based on her own past medical history and family history was revealed as a woman at significant risk for repeat miscarriages. After only a single prior miscarriage, she had to be viewed as a potential repeat immune aborter. She, in the CHR’s assessment, instantly, was no longer an infertility patient, but also a potential miscarriage patient.

After chromosomal abnormalities, a hyperactive maternal immune system (mostly due to autoimmunity and inflammation) is widely considered the second-most common (and most controversial) cause of repeat miscarriages.2 Here is an additional very important point: If one looks at the so-called natural history of women with repeated immune miscarriages, it starts with one or more miscarriages (likely more often male than female pregnancies). This is not where things end. At a certain point, these women, suddenly, no longer get pregnant. In other words, they develop secondary infertility, usually associated with POA. Almost uniformly, when we see patients with a history of one or more miscarriages followed by POA and/or secondary infertility, the common denominator is usually a hyperactive maternal immune system, most frequently evidence for autoimmunity and/or inflammation.

Then, such-affected women not only require help in achieving pregnancy, but also need treatments to be able to maintain their pregnancy without miscarrying. The earlier such patients are identified, the more miscarriages can be prevented. Consequently, the CHR strives to diagnose these women not only after they already have lost three pregnancies but, as this case report so well demonstrates, hopefully, much earlier.

Two more important points: Textbooks to this day are not only behind when suggesting that it takes at least three consecutive clinical pregnancy losses to diagnose a woman as a repeat (immune) aborter. They are also mistaken when demanding that these losses be “clinical.” “Chemical” pregnancies, have, indeed, been demonstrated to have the same diagnostic significance as “clinical” miscarriages in reaching a diagnosis of repeat (immune) pregnancy loss. The other important point to remember is that, while a majority of miscarriages are the consequence of chromosomal abnormalities in the fetus, considering the “wisdom of nature,” those are mostly early miscarriages before the fetal heart. Therefore, the later a miscarriage occurs, the less likely is it due to a chromosomal abnormality in the fetus and the more likely is the cause a maternal immune problem.

Finally, there also exists several other additional maternal problems that can lead to pregnancy losses, including uterine abnormalities, medical maternal problems during pregnancy, and pregnancy complications. However, the diagnoses of all of these problems is usually much more obvious.

REFERENCES

1. Li et al., Ann Med 2021;53(1):841-847

2. Baxi LV, Pearlstone MM., Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165(5):P1423-1424

3. FERTILE BATTLE. Odendaal et al., Fertil Steril 2019;112(6):1002-1006

22 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice Continued from page 21

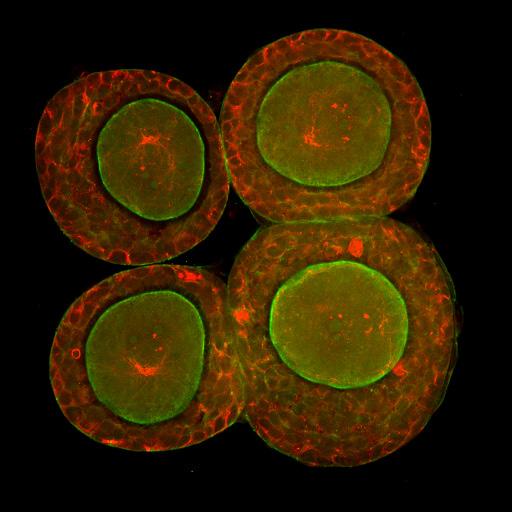

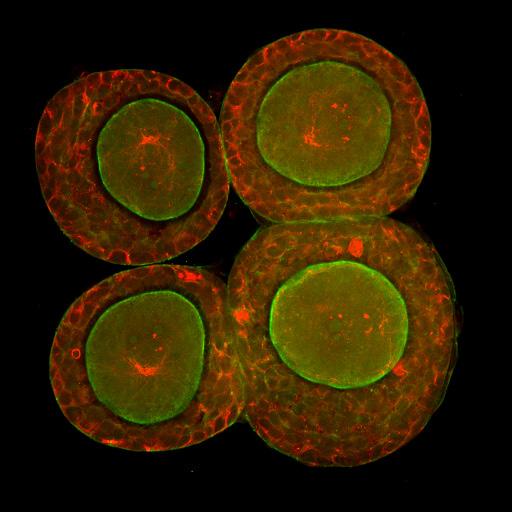

A longstanding collaboration with the Brivanlou laboratory at The Rockefeller University produced this image of a human embryo that was donated for research. Investigators used a variety of antibodies to stain this embryo with different fluorescent dyes allowing them to identify the various cell types that emerge to form both precursors of the placenta and yolk sac as well as the embryo proper.

Photo Gallery

Capturing oocytes at the earliest stages of their development is one of the challenges being confronted by investigators at the CHR. Here we see four early stage so-called pre-antral follicles that have been labelled to understand how the oocyte cytoskeleton contributes to establishing the shape and physical relationships with outer granulosa cells. The green staining reflects the protein actin at the oocyte boundary whereas the red stain illustrates the network of microtubules both within the oocyte (center of each of the four follicles) and in associated granulosa cells.

DR. ALBERTINI’S

Image 2

The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 23

Image 1

NEW CHR PUBLICations

Gleicher N, Darmon S, Patrizio P, Barad DH. The utility of all-freeze IVF cycles depends on the composition of study populations. J Ovarian Research 2923;16:190

The CHR’s investigators in this manuscript tackle a subject dear to our heart, - the importance of patient populations in whom studies are performed for the interpretation of study outcomes and the applicability of conclusions to different patient populations. This manuscript addresses this issue regarding the claim made by some colleagues that all-freeze cycles with subsequent thaw cycles offer better IVF outcomes than immediate fresh transfers.1,2 Even though this claim has been convincingly rebutted,3,4 the practice, like many other “add-ons” to IVF, unfortunately, continues rather unabetted, partially encouraged by the ASRM by recognizing it in its annual clinic reporting scheme as a formal cycle outcome option.

To explain the discrepancies in reported outcomes with all-freeze cycles, the CHR’s investigators in this study that was modelled from retrospective anonymized electronic CHR data selected patient populations and compared in those varying patient populations the clinical utility of all-freeze IVF cycles. As expected, depending on patient populations in which these comparisons were made, the effects of all-freeze cycles varied greatly, reemphasizing the point that medical journals in the infertility field must pay more and better attention to the, unfortunately, widely-spread practice in the field of performing studies in highly selected (often best-prognosis) patient populations and then extrapolating the conclusions of these studies to completely different patient populations.

REFERENCES

1. Shapiro et al., Fertil Steril 2013;99(2):389-392

2. Shapiro et al., Fertil Steril 2014;102(1):3-9

3. Wong et al., Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;61(1):52-57

4. Maheshwari et al., Hum Reprod 2022;37(3):476-487

CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR CHR

ADVERTISEMENT 24 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice

UESTIONSPATIENTS AND THEPUBLIC ASK

QCan I use DHEA and myo-inositol together?

We see with increasing frequency, patients who were prescribed DHEA as well as myo-inositol, and that, in most cases makes little sense because both supplements oppose each other in a very important function: As the precursor of testosterone, DHEA increases androgen (male) hormones, while myo-inositol reduces androgens. Consequently, DHEA supplementation is often indicated in women with infertility who demonstrate low androgen levels, such as women above age 38-40, women with premature ovarian aging, and several other rarer causes of female infertility. In contrast, myo-inositol is indicated in women with abnormally high androgen levels (most but not all PCOS patients), but also has several other potential indications, mostly relating to insulin and gonadotropin signaling.1

The first question to ask when considering either DHEA or myo-inositol supplementation is what are a patient’s androgen levels? DHEA should be only prescribed if androgens are low, and myo-inositol should only be prescribed if androgens are too high. If this first ground rule is followed, there will be very few instances where the possibility of prescribing DHEA and myo-inositol together will even come up. These possibilities will arise only if other than high androgens demand the prescribing of myoinositol.

What could those be? There have been suggestions of marginally improved pregnancy chances in IVF cycles,2 but the quality of this and other studies claiming outcome advantages in fertility treatments was uniformly quite poor. In short, there is no serious evidence for improvements in outcomes of fertility treatments in women with normal (or low) androgen levels if supplemented with myo-inositol.

We usually agree with many, if not most, recommendations Rebecca Fett, the author of ”It Starts with the Egg,” makes in her book (a 3rd edition was just published), and recommend it to our patients. In a recent mailing to her followers on August 20, 2023, she, however, seeded confusion when correctly noting that “the value of myo-inositol outside of PCOS is still uncertain. She then continued into somewhat controversial areas when stating that with “insulin resistance or high fasting insulin levels, which can cause lower percentages of mature eggs in IVF and low fertilization rates as well as recurrent miscarriages … women should be talking to their doctor about supplementing with myo-inositol.” She further claimed that “myo-inositol appears to help ovarian follicles respond to FSH,” and that “new studies indicate that in women with very high FSH levels and poor follicle growth in IVF, supplementing with myo-inositol may help ovarian cells respond better to FSH.” The latter is exactly what androgens (and IGF-1, - i.e., human growth hormone) are doing. Her bottom line was that, “if you have low testosterone and low DHEA but also have insulin resistance and low fertilization rate in IVF, it is possible that taking both, myo-inositol and DHEA, could be helpful.”

Continued on page 26 The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 25

Everything “is possible,” but to practice medicine is to make risk-benefit decisions whenever an intervention is considered. If this is done, considering the potential risks of adversely affecting female fertility by reducing androgens - against no realistic potential benefits - we would argue that combining DHEA and myo-inositol supplementation, simply, doesn’t ever make sense. If a patient has insulin resistance, why not place her on metformin, even that should be done only cautiously.

REFERENCES

1. Gambioli et al., Pharmaceuticals (Base); 202114(6):504

2. Lisi et al., Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012;10:52

I am HIV-positive, and we want a baby: what now?

The first question is, who is HIV-positive? One partner or both? If it is only one partner, are you making sure you are protecting the other partners from getting infected? Is the infected partner taking prescribed medications? If both of you are infected, are both of you regularly taking your medications?

Being infected with the virus is no longer the death sentence it used to be in the early days of the AIDS epidemic. If infected women and men take their prescribed anti-viral medications, their viral load usually becomes “undetectable,” AIDS becomes a chronic condition, and patients can experience a normal lifespan.

When it comes to having a baby, there are differences between infected males and females. Let’s start with males in this case: If a male has an undetectable viral load, the semen is with overwhelming likelihood not infectious. Most fertility centers, therefore, have no problem handling such semen. The story is a little different if the male’s viral load is not at undetectable levels. In such a case, the semen is still infectious and a male with a detectable viral load can (and likely will) infect his female partner if a condom is not used during intercourse. For fear of contamination, most fertility centers in such cases will refuse to work with the semen of such individuals until their viral titers become “undetectable” after appropriate treatments.

If the female is infected but has undetectable viral levels and wants to become pregnant, she is free to proceed for as long as she continues to take her medications uninterrupted throughout her pregnancy. The reason is that, if her newborn baby then receives anti-HIV medications after birth for 2-6 weeks, the chance of the baby being infected by HIV becomes negligible (less than 1%).1

A final word on HIV and getting pregnant: There exists increasing evidence that infertility may be increased in women with HIV. One reason is that their ovarian reserve (the number of remaining eggs in ovaries) appears to be diminished.2

A low ovarian reserve may also be a price to pay for getting great treatment with contemporary anti-retroviral drugs because, at least in some small animal models, these drugs have been demonstrated to disrupt follicle development.3 If you are a young HIV-positive woman who is in treatment and is planning to have a baby sometime in the future, we recommend that you ask your gynecologist to regularly, every year or two, check your ovarian reserve. You also may want to consider freezing your eggs while you are still young.

Anti-viral HIV treatments have also been reported to adversely affect semen analyses (mostly motility).4 However, the reason why declines in male fertility have been reported in association with positive HIV status, is not clear yet.5

REFERENCES

1. HIV.gov. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/ hiv-prevention/reducing-mother-to-child-risk/ preventing-mother-to-child-transmission-of-hiv/

2. Van omen et al., AIDS 2023;37(5):769-778

3. Aijbaye O, Taylor-Robinson SD., J Exp Pharmacol 2023;15:267-278

4. Jerónimo et al., Hum Reprod 2017; 32(2):265-271

5. Akang EN, et al., Andrologia 2022;54(11):e14621

Do Vitamin D levels affect IVF outcomes?

The effects of Vitamin D levels on female and male infertility have remained controversial. A recent review of the literature regarding the effects of the vitamin on males concluded that vitamin D plays a role in male reproduction, exerting positive effects on semen quality, especially on sperm motility in, both, fertile and infertile men.1 Available data for clinically significant effects on IVF cycle outcomes, however, are lacking.

The situation on the female side is similar: Vitamin D supplementation appears to impact gene expression in granulosa cells,2

Continued from page 25 26 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice

and does not appear to have any effects on cytokine/chemokine levels in uterine fluids.3 Effects have been suggested in PCOS patients and a prospectively randomized study of vitamin D supplementation before IVF in women with PCOS was announced in 2020 but has not been published yet.4

The CHR supplements patients with low vitamin D, we recently looked retrospectively at a large number of women who underwent IVF cycles at the CHR at their initial presentation to the center to see how their vitamin D levels related to their AMH levels (representing ovarian reserve). Interestingly, at first glance, the results suggested an opposite effect from what had been expected (see the Figure below): AMH levels were the best with the lowest vitamin D levels. Once this correlation was adjusted for female age, most of the gradient disappeared. In other words, at least on first look (and not published yet), the CHR’s new patients did not demonstrate a statistical association between vitamin D levels and ovarian reserve.

Stem cell treatments in infertility?

It suddenly seems like stem cells are everywhere in fertility treatments. It all started over 12 years ago when Indian investigators reported the first case of an allegedly successful autologous bone marrow stem cell transplant in a woman with severe Asherman’s syndrome.1 This was followed in 2014 by a report by Yale University investigators on a murine model that supported the notion of bone marrow-derived stem cells improving Asherman’s syndrome.2 In the same year, another Indian group reported successful injection of bone-marrow-derived mononuclear cells sub-endometrial into the endometrial cavity.3 The concept entered more mainstream in the field around 2016 when Spanish investigators first reported in a mouse model that human CD133+ mesenchymal bone marrow-derived stem cells promote endometrial repair after injury.4 This was followed up by the allegedly successful treatment by the same group of investigators of 11 women with Asherman’s syndrome with autologous CD133 + bone marrow-derives stem cells injected into the uterine vasculature.5 So far, this group of investigators unfortunately have not followed up since with a larger series of patients, as one by now would have expected. Nor have others reported on experience with such treatments with sufficiently large case numbers to reach serious conclusions about the efficacy of such treatments, though additional small case series have been reported,6 as have been further animal model studies in support of the concept.7, 8

Investigating the association of vitamin D levels in newly presenting infertilewomen at the CHR, AMH levels were, as the figure demonstrates, inversely related to vitamin D levels: Best AMH levels were associated with the lowest vitamin D levels. This unexpected finding, however, almost completely vanishedonce data were adjusted for female age, suggesting that this initial observation was mostly driven by patient ages and, therefore, did not suggest any causality.

This does not mean that vitamin D levels may not have positive or negative effects in IVF cycles on some subpopulations, but, overall, there appears no strong effect one way or the other.

REFERENCES

1. Calagna et al., Nutrients 2022;14(16):3278

2. Makieva et al., Hum Reprod 2021;3691):130-144

3. Cermisoni et al., Hum Repod Open 2022;(2):hoac017

4. Hu et al., BMKJ Open 2020; 10(12):e041409

This concept was seriously questioned when Australian, Chinese, and U.S. investigators questioned the ability of bone marrow-derived stem cells to transdifferentiate into the endometrial stroma, epithelium, and/or endothelium.9 Since then, an additional study reporting on 25 patients receiving bone-marrow-derived stem cells, injected sub-endometrial, has been reported by the previously noted group of Indian investigators.10 Moreover, Chinese investigators suggested that cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells may (at least in animal models) also be effective in repairing Asherman’s syndrome.11 Another group of Chinese investigators found umbilical cord stem cells installed over two consecutive cycles into the endometrial cavity effective in treating thin endometrium following Asherman’s syndrome.12 A single case from the Indian group reported on the successful treatment of a woman with bone marrow-derived stem cells after genital tuberculosis.13 Turkish investigators reported improvements in endometrium after two injections of bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells into the endometrial-myometrial junction within one week.14

The variability of methodologies and the anecdotal nature of published reports based on small numbers of patients and variability in underlying uterine conditions at present, therefore, raise serious questions about the utility of the concept of treating Aschermann’s syndrome (and thin endometria) with mesenchymal stem cells.

Injection of mesenchymal stem cells into ovaries in women with POI/POF or for what widely has been called “ovarian rejuvenation,” has also been proposed.15 Available valid data in support of this proposition is just as limited, even though the number of publications significantly exceeds stem cell use for uterine pathology. Here are selected findings of interest: Human amniotic epithelial cells are

Figure: Correlation between vitamin D levels and functional ovarian reserve, as assessed by AMH levels

Continued on page 28 The V oice | OCTOBER 2023 | 27

of low immunogenicity and have similar features to stem cells. They have been used in animal models to test the hypothesis that stem cell injections into ovaries can reverse cyclophosphamide-induced POI/POF.16 Iranian investigators demonstrated that intra-ovarian placement of autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells appears safe and leads to (inconsistent) declines in FSH levels in POI/POF patients.17

Aside from innumerable animal studies suggesting a “rejuvenating” effect of stem cell injections into POI models, two cases of allegedly successful intraovarian autologous stem cell treatment for low functional ovarian reserve in women were again reported by Indian Investigators.18 Iranian investigators claimed improved outcomes following intraovarian administration of autologous menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in women with the ESHRE definition of POI/POF (which is FSH below 20.0mIU/mL rather than the U.S. definition which requires an FSH of >40.0mIU/mL), 19 which under CHR criteria represents POA patients. A recent Chinese systematic review and meta-analysis reported 26 animal studies and six clinical studies on the subject. The clinical studies suggested that stem cell therapy may marginally decrease FSH levels (P = 0.04) but very significantly may increase antral follicle count (p < 0.00001), pregnancy rate (p < 0.01), and live birth rate (p < 0.001). Yet, interestingly, the study demonstrated no improvement in menstrual function, oocyte numbers retrieved, and embryo numbers obtained.20 Moreover, the Spanish group of investigators previously referred to regarding the use of stem cells for Asherman’s syndrome, in a review of the subject concluded that follicle reactivation techniques in models appear promising but current evidence is still too scarce to warrant clinical use 21 (beyond experimental protocols with appropriate consents).

REFERENCES

1. Nagori et al., J Hum Reprod Sci 2011;4(1):43-48.

2. Alawadhi et al., PLoS One 2014;9(5):e96662

3. Singh et al., J Hum Reprod Sci 2014;7(2):93-98

4. Cervelló et al., Fertil Steril 2015;104(6):1552-1560

5. Santamaria et al., Hum Reprod 2016;31(5):1087-1096

6. Zhao et al., Sci China Life Sci 2017;60(4):404-416

7. Sahin Ersoy et al., ol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2017;4:169-177

8. Liu et al., J Cell Mol Med 2018;22(1):67-76

9. Ong et al., Stem Cells 2018;36(1):91-102

10. Singh et al., J Hum Reprod Sci 2020;13(1):31-37

11. Lv et al., Mol Reprod Dev 2021;88(6):379-394

12. Zhang et al., Stem Cell Res Ther 2021;12(1):420

13. Patel et al., Clin Exp Reprod med 2021;48(3):268-272

14. Arikan et al., J Assist Reprod Genet 2023;40(5):1163-1171

15. Gao et al., Tissue cell 2022;74:101676

16. Zhang et al., Am J Transl Res 2020;12(7):3234-3254

17. Mashayekhi et al., J Ovarian Res 2021;14(1):5

18. Tandulwadkar et al., J Obstet Gynecol India 2022;72(suppl 2):458-460

19. Zafardoust et al., Arch Med Res 2023;54(2):135-144

20. Hu et al., Arch Gynecol Obstet 2023;doi: 10.1007/s00404-023-07062-0, Online ahead of print

21. Pellicer N, Cozzolino M, Diaz-García C, et al. Reprod Biomed Online. 2023;46(3):543-565

Continued from page 27 ADVERTISEMENT 28 | OCTOBER 2023 | The Voice

RECENT LITERATURE, relevant to REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE

Mostly placed into a clinical context, we in this section of the newsletter offer commentaries to a broad survey of articles in the English literature, usually published in the preceding month, which the CHR found of interest to the current practice of clinical reproductive endocrinology and infertility, - even if at times not immediately applicable to daily clinical practice. Since this is the first issue after the newsletter’s summer break in July and August, we this month offer almost three months of literature review.