BEYOND THE ORDINARY

The two legends of alpine skiing on friendship and rivalry, falls and rebirth

nly the Brave” isn’t just a motto. It’s also the starting point for the winter season about to begin, featuring two skiing legends, Sofia Goggia and Lindsey Vonn (p16), who have used courage as an essential tool to become the athletes they are today. “Without my falls, my injuries and my successful comebacks, I wouldn’t be me.” Guess which of the two said those words… either could have.

This is the kind of courage that’s necessary to make your mark in sport, whether you’re a promising young talent just starting out, with bravado and doubts typical for your age (p30), or someone who’s ditched the training method you’ve been following for years and chosen to embrace new, revolutionary technologies (p52).

Page after page, it gets clearer just how brave you become each and every time you put yourself out there.

The editorial team

Valerio Mammone

Journalist and editorial coordinator of this issue of The Red Bulletin. He edited the section dedicated to training.

Margherita Tizzi

Founder of Mntn Journal, a magazine about skiing and the mountains, Tizzi interviewed our cover stars and Dominik Paris, and wrote ‘New Scene’.

Ario Mezzolani

‘Head of eating and drinking’ at Zero.eu, Mezzolani compiled and wrote our handy guide to six Alpine resorts.

Technology and new professionals are rewriting the science of performance, making it increasingly targeted and personalised

with one of the greatest downhill skiers of all time

How a biathlon icon trains: Dorothea talks us through her preparation regime

Snowboarding photography is peppered with adrenaline-pumping images. Photographer Carlos

is a master like no other in this regard

161.9 kph

In downhill races, athletes can exceed 160kph. This is particularly impressive when you consider air resistance, irregularities on the slope, and the pinpoint accuracy required for every movement. The all-time record is currently held by Johan Clarey, who hit 161.9kph on the Lauberhorn course. Pictured: Italian skier Dominik Paris (interview on page 60) during the Hahnenkamm Race trials in Kitzbühel, Austria.

Extreme speed, record-breaking jumps, elegance and precision: in winter sports, athletes face the constant challenge of pushing the limits of the human body and the laws of physics

Cross-country skiing marathons are often mass gatherings. The oldest and most popular event is Vasaloppet in Sweden – this 90km classic-technique race attracts around 16,000 participants annually, bringing together both elite and amateur skiers. The next most popular is Switzerland’s Engadin Skimarathon (pictured: one of its most spectacular sections), with 42km of skate skiing and more than 13,000 enthusiasts. In third place is the American Birkebeiner in Wisconsin, a 53km race that draws around 10,000 participants each year. In Italy, the Marcialonga takes 7,000 cross-country skiers across 70km between the Fiemme and Fassa valleys.

Biathlete Dorothea Wierer fires around 20,000 rifle shots in training every year. To achieve her signature speed at the firing range, she not only spends hours perfecting her position and movements but also practises exercises to halt her breathing even when her heart is pounding at 180 beats per minute. In our interview on page 66, Dorothea gives a detailed rundown on how her training sessions are structured. Pictured: the Italian champion during the women’s 4x6km relay race at the Biathlon World Championships in Lenzerheide, Switzerland. 20,000

When ice skaters land a triple or quadruple Axel jump, they experience a ground reaction force equivalent to three-to-four times their body weight. In less than a tenth of a second, a 60kg athlete ‘absorbs’ up to 240kg on a single leg while maintaining their balance and posture (and sometimes even a smile on their face).

In Iceland in 2024, Japanese ski-jumping icon Ryōyū Kobayashi launched himself off a ski jump and landed 291m away. This unprecedented feat was performed outside official competition and is therefore not formally accredited. The official record had been set in 2017 by Austrian ski-jumper Stefan Kraft, who covered 253.5m, before being broken in March 2025 by the Slovenian Domen Prevc with a 254.5m jump.

We get up close and personal with Lindsey Vonn and Sofia Goggia to talk about rivalry, respect, and always living life on the downhill

Words Margherita Tizzi

“WE’RE

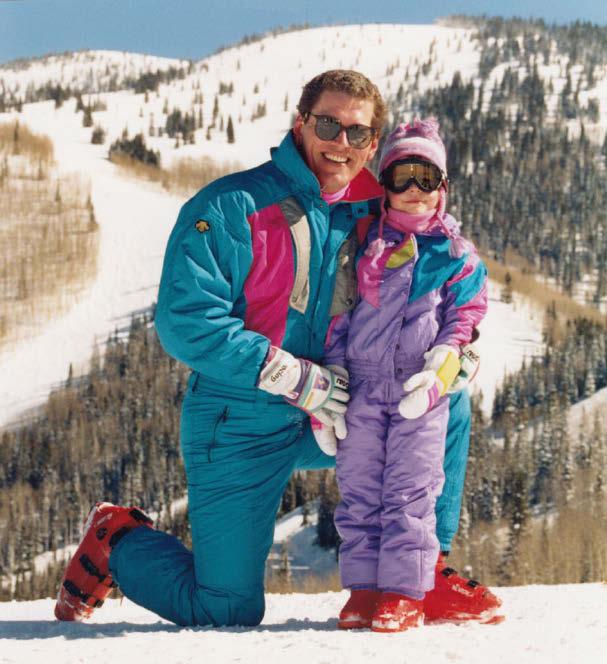

Her first time on skis at three and a half: this is how Vonn’s extraordinary story started

When you’re a pro skier, you know that, somewhere in the world, someone is doing the exact same thing – and one day they may beat you. If friendship is one of the values on which sport is based, sometimes great rivalries can be divisive. But, as athlete Jesse Owens said of his friendship with rival Luz Long, “awards become corroded, friends gather no dust”. This is how Lindsey Vonn and Sofia Goggia see it –the skiers’ bond came about thanks to shared experiences, successes and defeats.

11-year-old

of and I have been through so much together,” says American downhill skier Vonn. “We put the same passion, energy and determination into our sport.” It’s a connection that goes beyond competing; one “that has allowed us to mature, grow and support each other, enriching our personal and sporting lives”, says Italian champion Goggia. What you’re about to read is not just an interview but a legacy; a conversation to refect on and aspire to.

the red bulletin: What do you remember about those early years when you frst began skiing?

lindsey vonn: I started when I was very young, about three, in Minnesota. I remember it was so cold that my father – a lawyer and ski instructor at the time – would always buy me hot chocolate and doughnuts to convince me to ski. I hated the cold.

sofia goggia: I braved the cold to copy my brother, who’s three years older. I wanted to do everything he did, and I cried the whole winter when I was three because he was allowed to ski and I wasn’t. My mother was so exhausted that the next year she literally sent me with him. We started skiing at a tiny ski area with three chairlifts near Bergamo, but I never noticed [how little it had] to ofer – that was thanks to my instructor, Nicola, who thought I had talent. He convinced me to pursue this path. We may not have had much there, but we did have a vision, a goal, a dream. And, to us, that was everything.

What does skiing mean to you?

vonn: Everything. The mountains are my happy place, where I fnd and feel joy. I feel freer [there] – stronger, more present, like anything is possible. There’s nothing better than skiing, going fast, racing. I grew up training. There was nothing else to do in

Minnesota, and I wasn’t very good at sports. I competed in my frst race at seven. Then and now, I’ve always been very competitive – it’s why I’m still here, why I came back. Despite all the falls, the sufering, how I feel about this sport will never change. Falling is just part of our job. I think Sofa sees it the same way. goggia: Absolutely. Especially if we’re talking about a love of speed. If you ask Nicola for a memory from when I was little, he’ll tell you about when I was always frst, never second, in our races across the plateau that linked the Foppola and Carona slopes. Like Lindsey, I’ve been guided by a sense of competition.

What was it your brother used to say about you being smaller but more “awkward”?

goggia: He never had a killer instinct at the starting gate. He never liked pushing himself

beyond his limits. But I did, and I think skiing is a refection of my character, of what’s inside me. This is why I’ve never managed to keep my work and private life separate: who I am from what I have to do. The same is true for my feelings. I’ve tried many times in my career, but I just can’t do it. When I ski, I give everything. There’s a saying in English: “You’re the strongest weakest link.”

How do you become Lindsey Vonn and Sofa Goggia? What’s the physical and mental preparation like?

vonn: It’s changed a lot over time, and with time – especially now, having been away for so long. How I train, what I eat... it’s all diferent, because my body is diferent. With my ‘new’ knee, thanks to science, I can now train more intensely and in a smarter

Sofia Goggia tightens her ski gloves before a descent in Val di Fassa

way, but I take experience into my races. I can’t think about challenging a young person’s body like I did 20 years ago. In the World Cup, everyone is a good skier, but not everyone can handle the pressure in important races. Mental performance changes everything.

goggia: It changes so much that when we’re feeling good about ourselves, when our emotions are in check and we trust in our abilities, even if our body is [only] at 60 per cent, we can still get a podium fnish. On the other hand, if your body is at 100 per cent but your head isn’t there, you won’t perform well, I can assure you. Of course, the best possible ftness training is fundamental, especially now with the new equipment. Skiing makes you age more quickly. It’s stressful, but, as Lindsey said, at the top [of the sport] all the athletes have the same potential, and what really makes the diference is learning how to manage your emotions. The more that time passes, the more you have to feel good about yourself; you have to protect your serenity. I’m not just talking about mental preparation, but something deeper. It’s about connecting with the right part of yourself.

Has that part of yourself ever been afraid of a descent?

vonn: If you’re a downhill skier and you’re afraid, you’re in the wrong job! Going fast is what we do, it’s what’s expected from us, so fear doesn’t even go through our minds. I was away for a while [following my retirement] and I had to get through some major surgeries. But I couldn’t wait to come back, because I’m all about speed. That’s one of the many things that links me to Sofa. goggia: Lindsey is right. Perhaps I’ve experienced fear sometimes, but not in the negative sense of the word. If fear is an emotion that you’re brave enough to listen to, it can be a resource, a guide. We both know that there’s a risk involved in our job, but you can’t focus on that. Instead, you have to focus on your skills, qualities, and the fact that you can do it. We can be distracted by what’s inside us, not by what’s around us. And if we feel fear, it’s not about skiing but about other aspects of ourselves.

Sofia Goggia was born in Bergamo in 1992 to an Italian and Latin teacher and a civil engineer. She made her debut on the FIS (International Ski and Snowboard Federation) circuit in 2007, but her breakout season came in 2016/17 with 13 overall World Cup podiums and a thirdplace finish in the overall ranking. This would lead to the downhill gold medal in Pyeongchang and the World Cup downhill season title in 2018, making Goggia the first Italian woman in history to win both in the same year. She’s still the only Italian woman to have won four downhill World Cup titles. But something you perhaps didn’t know? Goggia is a partner

in Le Selvagge, an organic farm that rears around 2,500 Leghorn chickens who roam free in the woods, listening to classical music. Her own playlist ranges from classical to soundtracks and Latin: who could forget her samba – a tribute to Brazilian champion Lucas Pinheiro Braathen – after winning the Super-G at Beaver Creek in the 2024/25 season?

Goggia’s strength is a combination of talent, discipline and resilience. She’s come back several times after serious injuries and turned every fall into a fresh start, becoming a symbol of courage and uncompromising determination to her fans.

Goggia celebrates after finishing third in the World Cup combined at Val-d’Isère in 2016. It was her fifth podium of the season in four disciplines – an Italian record.

Goggia takes a break in the mountains between training and racing. The champion from Bergamo recharges her batteries as she looks out over the peaks – her natural habitat and the scene of her numerous achievements.

“In the toughest moments, my skis were there, pushing me to get back on my feet, to get the best out of myself”

Sofia Goggia

Vonn has always had a special relationship with her father, the first person to take her to the ski slopes. In a post in 2019, she publicly thanked him for being there for her at all times: “You were there for me from the beginning, and you were there for me at the end. I couldn’t have asked for a better way to finish my career than with you by my side.”

“ When I’m away from skiing, I can’t wait to get back to the slopes. I’m all about speed, and that’s one of the many things that links me to Sofia” Lindsey Vonn

Vonn remembers what sport meant to her while growing up: “Sport has taught me trust, discipline and determination. During my career, I’ve met people who thought I couldn’t do it. Those doubts only fuelled my fire.”

The American was already racing at the age of seven. At 13, she was accepted onto a USA team programme for young skiers aged 14-19. The following year, in 1999, she won the Trofeo Topolino – the first American female skier to do so.

Ruthless, dominant, brilliant, tenacious: a legend of the sport

Forty-three World Cup downhill wins and twenty ‘crystal globes’. There’s never been anyone like her in the history of women’s alpine skiing. Lindsey Vonn is a myth and an icon. Born Lindsey Caroline Kildow in Saint Paul, Minnesota, on October 18, 1984 – the surname Vonn comes from ex-husband Thomas, a famous US skier – she made her World Cup debut at 16. By 18, she’d already won three downhill world titles; an avalanche of triumphs and records would follow. These included the highest number of wins on the same slope: 18 (from 44 starts) at Lake Louise in Canada. In 2019, Vonn announced her retirement due to continued

injuries to her knee, which had to be reconstructed. She made a surprise comeback to racing in the 2024/25 season, aged 40, and won silver in the Super-G in Sun Valley, becoming the oldest female skier to achieve a World Cup podium finish. “I believe in the impossible,” the champ posted on Instagram. “I am a strong woman who loves to ski. I will fight to do what makes me happy, and I encourage all of you to do the same. Life is too short to sit on the sidelines”.

The American repeats this message in Lindsey Vonn: The Final Season, a documentary that tells the story of not only her victories but her failures, too.

Vonn celebrates after coming second in the women’s World Cup Super-G at Sun Valley, Idaho, in March 2025

Is there a photo, a moment in your career, that still makes you emotional?

both: [Excitedly] The win in Cortina! vonn: And winning all the most emotional, psychological and toughest downhills of my career, because I lived under huge pressure for years.

What’s so special about Cortina?

vonn: It’s a place where I feel profoundly connected to the mountains. In Lake Louise and Cortina, the mountains understand me, and I understand them. I got my frst World Cup podium at the Olimpia delle Tofane in 2004; it’s where I understood the key to my success and where I did my last run before retiring. Sofa was injured, but she drove for fve hours to see me and to bring me fowers. I was hoping that it would be a good race at least! [Laughs.]

goggia: I knew her knee wasn’t good and that she was struggling to ski. I said to myself, “I have to go to Cortina for what’s probably going to be her last downhill.” I was wrong, luckily. How many times have you won there?

vonn: Twelve in total, between downhill and Super-G.

goggia: Wow! [Turns to the Red Bull team in admiration.] Coming back to Cortina, it’s true that we both have a special connection to the mountains. The Olimpia delle Tofane is the queen of downhills. There’s something magical about the landscape. When we take the Duca d’Aosta chairlift for the pre-race inspection, surrounded by silence and the dawn that tinges the Dolomites with orange, you feel really grateful to God.

vonn: It’s magnifcent.

goggia: I almost forgot – it was in Cortina on January 19, 2015, that I had my frst photo taken with Lindsey.

vonn: Really?!

goggia: I was just a kid – I was 23 at the time. The season after that was when I started doing well and I got my frst World Cup podiums. Also in Cortina, in 2018, I won my third downhill gold, my frst at home. There really is something special about doing it in front of your own fans.

“If you feel good about yourself and can protect your serenity, you can make it onto the podium, even if you’re not at your best. But if your body is 100 per cent and your head is somewhere else, you won’t perform well”

Sofia Goggia

Unlike in other sports, women fgure quite prominently in skiing, especially in Italy. What do you think, Sofa?

goggia: In the past few seasons, Federica [Brignone], Marta [Bassino] and myself have taken women’s skiing in Italy to an unprecedented level. And we shouldn’t forget the achievements of Deborah Compagnoni. But I always come back to the fact that if you add my and Federica’s podiums together, Lindsey has won as many on her own!

Your admiration knows no bounds… goggia: I feel very small next to her. vonn: Don’t forget you’re a champion. Remember? I think we’re the same person but just from two diferent countries. [Laughs.]

goggia: You’ve won much more than me. You’re Lindsey Vonn, and it’s an honour for me to race with you. You’ve always inspired me, you know? As you guys will have understood, there’s a great respect between us; a close understanding due to our injuries and being able to come back stronger than before. I’m grateful to have had the chance to share some fantastic moments with Lindsey. The cherry on top would be a podium together, on the highest step, at Cortina, of course.

Lindsey, tell us something we don’t know about Sofa…

vonn: Sof is tenacious, genuine, natural, honest and passionate. I love her posts on Instagram, because she’s always spontaneous, unfltered. She’s always herself, and we’re very similar in that way. After my father, she was the frst person I told about my comeback.

goggia: We trust each other, and I know she would be there if I needed her, and vice versa. Our relationship isn’t that common among athletes.

Where do you see yourselves in 20 years, after retirement?

vonn: I haven’t skied for six years, so I’m not thinking about anything else! [Laughs.] Ten years ago, if you had asked me the same question, I would never have imagined I would be here. At this point, I really don’t have any idea what life has in store for me.

goggia: As Forrest Gump says... both: [In unison, laughing] “Life is like a box of chocolates: you never know what you’re going to get!”

If you had to write a letter to your sport, what would you say in it? “Dear skiing...”

vonn: You’ve given me everything, and taken everything away from me at the same time.

goggia : Dear skiing, you’re a refection of myself, the way I express myself on good days and bad days. You’ve given me the medals I had been dreaming about since I was a child and allowed me to become an athlete – something I’m very grateful for, because it’s an absolute privilege. I’ve never hated you. In the toughest moments, I hated myself, but you were always there, pushing me to get back on my feet, to get the best out of myself.

vonn: Wow, Sof expressed herself much better than me, even though English isn’t her frst language. [This interview was conducted in English.]

What message would you like to leave for future generations competing in your sport?

vonn: Everyone falls in the mountains; it’s impossible not to. But picking yourself up and carrying on skiing teaches you what it means to persevere. When you’re at the top of a mountain looking down, you see a world of possibilities; it’s up to you to choose your path. It’s a great metaphor for life.

goggia: In her documentary, Lindsey says, “If you’re watching this flm, never ever give up, never lose faith in yourself. It’s the most important thing.” I try to remember that every day.

“I competed in my first race aged seven and, then and now, I’ve always been very competitive. That’s why I’m still here, why I came back. Despite all the falls, the suffering, how I feel about this sport will never change” Lindsey Vonn

Podiums, challenges and camaraderie: key moments in Vonn and Goggia’s careers and friendship

2016/17

A breakthrough season for Sofia Goggia: after 13 World Cup podiums in four different disciplines, she finishes third in the overall standings (pictured: she celebrates after one of her two victories in Jeongseon, South Korea)

Vonn wins her 20th crystal globe in St Moritz, becoming the athlete with the most crystal globes in World Cup history

The battle of 0.07s: February 2, 2017, World Championships in St Moritz: Vonn finishes third and Goggia fourth, with just 0.07 seconds separating them March 4, 2017, World Cup downhill in Jeongseon: Goggia wins her first World Cup singles race, beating Vonn by 0.07 seconds

2018

Goggia wins her first World Cup downhill title, becoming the first Italian to achieve this milestone

In January, Vonn competes in her last downhill race in Cortina. Goggia, sidelined by injury, greets her at the finish line with flowers

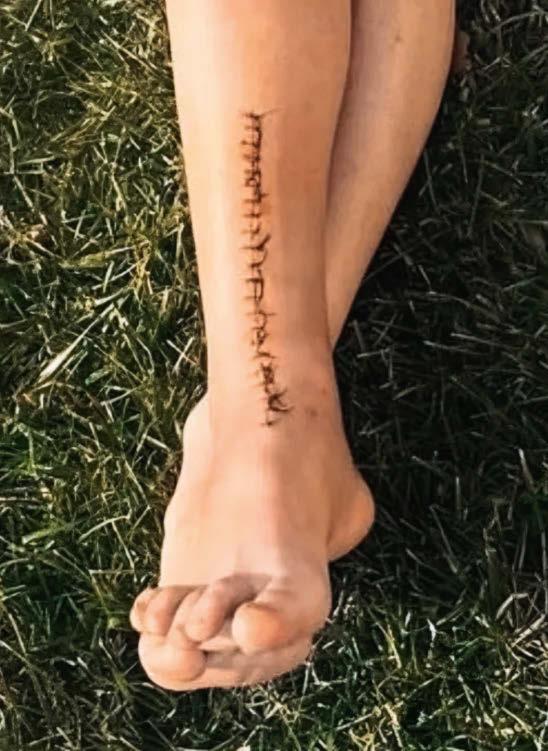

On February 5, Goggia suffers an injury during training in Ponte di Legno, resulting in a fractured right tibia and tibial malleolus that requires a plate and seven screws. The accident ends a season in which she’d been a leading contender in the World Cup downhill

World Cup Super-G in Beaver Creek: Vonn returns as a forerunner; Goggia, back after her tibia injury, listens to her friend’s advice over the phone before the race and wins by almost half a second

Aged 18 to 21, these talented athletes are set to write the next chapter in winter sports history. Flora Tabanelli, Lara Colturi, Laila Edwards, Isabeau Levito and Ian Matteoli are young prodigies on snow and ice, attracting attention for both their technique and their personality. With pre-season preparations underway, we met up with them in one of their rare breaks from training. Driven by sacrifice and dedication, determination and passion, their stories portray a generation ready to make its mark. Their goal: to continue to grow, push themselves even further, and secure a lasting place among the international elite.

Italian elegance, American talent: this athlete’s gracefulness has won people’s hearts and made her a key figure in the USA’s national figure-skating team

Though born in Philadelphia, Isabeau Levito has Italian roots, and Milan in her heart. Having started out on the ice at the age of three, she won gold at the 2022 World Junior Championships and silver at the 2024 World Championships.

“I love ice skating because I can play a diferent character every time, learn diferent dancing styles and, at the same time, stay very much myself,” says Isabeau Levito. Born in 2007, Levito is one of today’s rising fgure-skating stars. She has a close relationship with Italy, particularly Milan: her mother, Chiara Garberi Levito, emigrated from the city to the United States in the 1990s.

A precocious talent

Levito already has a series of impressive results behind her, earned through the quality and complexity of her programmes, which include very difcult jumps such as the triple Axel and the quadruple toe loop. Her achievements include a gold medal at the World Junior Championships in Tallinn in 2022, a national title in the USA in 2023, and silver at the 2024 World Championships in Montréal, which she won at the age of just 17. These three consecutive wins were followed

“I’m a perfectionist – I’m only satisfied if my lines are smooth”

by a serious injury to her right foot and a long recovery period.

Levito frst took up fgure skating at a very young age: “I started when I was three. My mother signed me up to help improve my balance, and I never stopped – I don’t know how to live without skating every day.”

At the age of 10, she saw Evgenia Medvedeva on TV for the frst time, and the Russian fgure skater became her muse and inspiration: “While I was watching her, I thought, ‘I want to be like her.’ She has really been my biggest inspiration.”

On TikTok, where Levito posts ironic videos that often show her on the ice, there’s not one comment that doesn’t praise her gracefulness, her elegance or, sometimes, her outfts.

“My style,” she explains, “is graceful and very reminiscent of ballet, because I’ve done a lot of classical dance. Growing up, I became a perfectionist – I only feel satisfed if my lines are smooth and complete.”

Like many athletes of her generation, Levito knows that success lies in the ability to deal with the pressure of competing in a healthy way: “When I was little, I was great at competing because all I thought about was skating smoothly. [But] as I got older, I started to think about winning; that’s when mistakes appeared. During a programme, my mind tends to wander, and I often fnd myself thinking, ‘What if I fell doing this triple fip? How many points would I lose? What position would I be in compared to the girl who skated before me?’ When I have these thoughts, I try to silence them and calm down, but that internal dialogue distracts me.”

Staying focused is one of the main skills that Levito is working on as she prepares for the competitions ahead of her. She’s not short of time or the ability to improve, and she’s bolstered by the support of her fans: “We’re lucky,” they write beneath her posts, “because we’ll be able to watch you skate for years to come.”

Instagram: @isabeau.levito

1. Training playlist

Justin Bieber Confident

Rihanna Don’t Stop the Music

Three 6 Mafia Stay Fly

2. Favourite movie My Girl

3. Favourite book

Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens

4. Best trip

Milan (obviously)

5. Favourite food Burrata and pasta with tomatoes, mozzarella, capers and olives

From

his first descents with his father to an early love of skateboarding, by the age of 11 this Italian athlete had the experience of a snowboarding veteran. Now he’s ready to steal the show

Italian snowboarder Ian Matteoli specialises in big air and slopestyle. His World Cup debut came in 2021, and his best results to date include a bronze and two silver podiums in big air, won between 2022 and 2025.

Ian Matteoli was the frst-ever snowboarder to complete a frontside 2160 – a jump with six spins before landing – in competition. The feat lasted only a few seconds, but it was enough to secure him a place in history. Performed in 2023 during the Stubai Prime Park Sessions, it left spectators speechless – even multiple medal-winning American Shaun White. The jump stemmed from a precocious dedication that has made Matteoli – at a very young age – one of the world’s most innovative and most followed riders.

Born in Turin in 2005, he was the frst Italian to climb the World Cup podium for men’s big air – one of his specialities, along with slopestyle and halfpipe. He achieved this result at Copper Mountain in 2022, when he unexpectedly claimed third place. Then, in Beijing in December 2024, Matteoli pulled of another frst by executing the frst 2160 in the history of the Snowboard World Cup, which earned him second place in a stage of the competition.

“I want to be innovative and competitive without going against my values”

“I was two years old when I frst got on a board in Bardonecchia and went downhill, obviously pulled along by my dad,” he says.

Having earned 17 wins in the Snowboard World Cup between 1989 and 1996, Andrea Matteoli went on to coach various national teams; he also lived in New Zealand, where his son could make the most of an extra winter on top of the European season.

“I was lucky to be able to travel the world and train in diferent places,” Ian says. “At the beginning, I just did it for fun, to follow family tradition. My father never pushed me to enter competitions; he left me free to choose my own path, especially because I also spent most of my summers skateboarding, another great love of mine.”

By the age of just 11, Matteoli had built up a level of expertise some snowboarders achieve over an entire career. He entered his frst European Cup competitions aged 13 and made his World Cup

debut at 15. Not even a serious injury in 2023, which led to the removal of his spleen, could stop him. It was, in fact, a precursor for his unforgettable feat on the Stubai Glacier in Austria: “From that moment on, I’ve always looked ahead.” The injury gave Matteoli a methodical and scientifc approach to training: “From the end of the season to the next pre-season, I train in an artistic gymnastics gym and in two artifcial facilities, one near Innsbruck, another in Japan. Both are hubs where you can simulate jumping and landing to improve your technique.”

Role models and style

“Snowboarding is a fun, creative discipline, but it’s also extremely difcult,” Matteoli says. “It takes the highest level of dedication and concentration, but the emotion you feel is so rewarding. It’s the sport that allows me to express my style. Take Taiga Hasegawa, a huge inspiration to me. Watch how he snowboards, the way he does certain tricks.”

Maintaining such high standards will take strength of character: ‘I’m putting in even more efort than usual right now. I want to keep being innovative and competitive without going against my values. I’ll look to Valentino Rossi and Marcell Jacobs – two great athletes who have taken Italy to new heights.”

Instagram: @ianmatteoli

Inside Ian: five fun facts

1. Training playlist

Black Sabbath

Paranoid

Sfera Ebbasta

Più forte

Future

Metro Boomin

Kendrick Lamar

Like That

2. Favourite artist

Virgil Abloh

3. Three great loves

Drawing, fashion and design

4. Best trip

New Zealand

5. Good-luck charm

My headphones. I take them everywhere –to training and competitions, and on holiday

There was only one hockey team in her city, and all the other players were male and white. But, thanks to her huge love of the sport, this American pushed through every barrier and ended up representing her country

Laila Edwards is the frst African American athlete to play for the USA national women’s ice-hockey team. A forward for the Wisconsin Badgers, in 2024 she won the Bob Allen Women’s Player of the Year Award.

Laila Edwards is a polite, sensible and incredibly mature young woman, with a contagious smile. She’s one of the USA’s best university hockey players and the frst Black woman to play for the national team. “Representing my country at the highest level is an honour, a goal I’ve been working towards my entire life,” she says, taking us through a journey that has been anything but easy. “I love this game, and I’m going to try to change the culture surrounding it.”

Breaking down every barrier

Born in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, in 2004, Edwards was frst introduced to hockey at the age of three: “It was my dad’s favourite sport, and soon it became a family thing. I thought it was diferent, fast and fun, especially because there was interaction and a sense of belonging when I played with him and my sister. At the beginning, there was only one

“My discipline in three adjectives: spectacular, intense, different”

team in my city, made up of white boys. I was a girl, and if that wasn’t enough, I was Black. There were times when I didn’t want to play any more. Some people thought there was something wrong with me, but with my family’s help I managed to push forward.”

So much so that “many women today would love to be her”, says Edwards’ coach, Mark Johnson, himself a star player in the ‘Miracle on Ice’ hockey team in 1980. Winner of the Bob Allen Women’s Player of the Year Award in 2024, she’s breaking down barriers and inspiring a new generation of athletes.

“I want to get better, not only for myself but for the sport in general,” Edwards says. “Hockey is my life, my job, and it’s only right that I do my best.”

Doing her best meant choosing the University of Wisconsin, which has one of the best Division I hockey

programmes in the United States. “I train for four or fve hours every day,” she says. “Warming up and stretching are crucial for good mobility and for preventing injury, while running or track and feld are useful for working on speed and a powerful sprint. I also enjoy basketball and pickleball – they’re great sports for improving shots and stickhandling agility. I play football with my teammates, too, which improves our coordination and communication and helps us work as a unit.”

Team game

Hockey is more than just a game: it means being there for each other, encouraging one another. “Unlike in individual sports,” Edwards says, “there are 20 of us sharing the emotions, fears and pressure. But at the same time, when you make a mistake, it’s harder to get past it because you feel like you’ve let the team down and that the defeat was your fault. And yet your team is always there, reminding you that you’re not alone.’

Instagram: @laila_edwards

Inside Laila: five fun facts

1. Training playlist Billie Eilish Bury a Friend, Birds of a Feather, Lunch

2. Favourite movie Miracle on Ice

3. Favourite book Anything by Jodi Picoult

4. Best trip Bolzano. I went there for a competition and have never forgotten the city, the people and the food!

5. Random talent I can say any word backwards

Born to two athletes, ‘Speed Girl’ (her Instagram nickname) is already a star of alpine skiing. In 2022, she decided to compete for the Albanian national team, coached by her mother, Daniela Ceccarelli

Specialising in giant slalom and Super-G, Lara Colturi made her World Cup debut in 2022. In 2024, she fnished second in the slalom in Gurgl – the Albanian national team’s best-ever result.

“My frst time on skis?” says Lara Colturi. “I was 13 months old, and it was during a World Cup.” In 2022, aged only 16, she would become the secondyoungest skier to participate in a World Cup competition. Colturi was born to compete in alpine skiing, which she considers “fast, elegant and hard”. She was born to two parents in the sport: her father Alessandro is a ski coach, her mother Daniela Ceccarelli a former professional skier and Super-G champion. Colturi followed her mother around the world before starting school at the age of fve. After discovering fgure skating early on, she eventually committed to skiing.

The price of talent

“It hasn’t been easy to balance my studies and sport, or to give up part of my youth,” Colturi says. “That’s why I always try to carve out time for myself to play the piano, do other sports –tennis with my brother Yuri, skating on icy lakes – and read novels, biographies and science books. Fun and distraction have to be priorities, because they make you feel good.” Rightly so,

“Training with idols I watched on TV as a kid is incredible”

because training (almost) never ends: six months of competing, then long periods of dry-land training (gym and bike) and skiing on glaciers, six days a week, four hours a day. These are crucial moments for concentration, of both body and spirit.

“It’s a routine that I saw my mother following, even when she was breastfeeding me,” Colturi says. “That’s why, although it’s difcult, it’s really incredible to be here today, hitting the slopes with Fede [Brignone], Mikaela [Shifrin] and many other athletes who competed with my mum and who I watched on TV or from the sidelines. Training with them and getting tips is a wonderful feeling. That in itself is a great experience.”

A difficult decision

In 2022, Colturi decided – with her parents’ agreement – to compete for Albania. This has provided more autonomy in creating her training regime and allowed her to test her skills by immediately competing in FIS categories against the world’s

best athletes (not permitted by the regulations of the Italian national team). Colturi is being coached by her mother, Daniela Ceccarelli – now technical commissioner of the Albanian national alpine skiing team – who has guided and supported the athlete since she was a child.

Colturi’s decision changed the course of history for Albanian skiing. Her unprecedented results include Albania’s frst gold at the Junior World Cup, victory in the 2022 South American Cup, and four FIS wins. And all this was achieved by the age of 18, with two impressive second-place fnishes in the slalom at Gurgl in Austria and the giant slalom at Kranjska Gora in Slovenia.

Lessons to learn

After four years competing in the World Cup, and an eightmonth break to recover from an injury, Colturi wants to keep improving her technique in the giant slalom and slalom, to get as close as possible to her own idea of perfection: “I like speed as well, which is why I’m going to try and go back to downhill, too. In this respect, my injury was useful, because I now understand how to read my body and how to listen to it.” Sacrifce, experimentation, fun: all words that sum up Lara Colturi’s skiing.

Instagram: @laracolturiofficial

1. Training playlist Olly Balorda Nostalgia Benson Boone Beautiful Things Rosé & Bruno Mars APT

2. Favourite movie La La Land – it reminds me of skating

3. Favourite book Senza permesso by Vincenzo Patella

4. Best trip Japan, combining nature, sports and culture. And the Stelvio Pass on skis, like my parents did on their honeymoon

5. Superstition I always put on my right ski boot before my left

Reserved in everyday life, yet astonishing on the slopes, this athlete has won it all before even turning 18, transforming from a promising talent into an undeniable rising star of Italy’s freestyle skiing team Inside Flora:

Flora Tabanelli is a freestyle skiing icon. In 2025, aged only 17, she won the overall crystal globe for park and pipe, the crystal globe for big air, and gold medals at the World Championships and X Games.

For Flora Tabanelli, freestyle skiing is a constant challenge, “a discipline not many people know, but which ofers unparalleled creativity and freedom”. The sport has helped her grow not only as an athlete but as a person, she says: “I’m quite introverted in real life, so freestyle helps me to open up and make a name for myself.”

Mission accomplished. In 2025 alone, the Bologna-born skier won the overall crystal globe – that is, the World Cup – for park and pipe, as well as the globe for big air. Most notably, Tabanelli became the frst-ever Italian woman to earn a win at the Aspen X Games – freestyle skiing’s most prestigious event. These triumphs have put her forward as the unrivalled queen of the sport. She feels the pressure but tries not to let it take over: “I don’t really like being in the spotlight, but I’ll keep on having fun and working hard to show what I can do.”

“When I was little, Tomba came to visit us in the mountains. It was fantastic”

Tabanelli’s training Study and preparation – gym workouts, aerobics, running, simulating jumps on Neveplast (artifcial snow) – are essential in freestyle skiing. “Artistic gymnastics really helps, too,”

Tabanelli says. “I’ve been doing it since I was two. It teaches you ‘awareness in the air’ – the ability to perceive and control your body mid-jump.” A combination of explosive strength, balance and creativity is at the heart of her most spectacular tricks, which include multiple jumps with technical rotations and grabs that have put her on top of the world.

Like many top athletes, Tabanelli enjoys trying out other sports: “I could never give up surfng or skateboarding, which are hobbies I share with my big brother Miro.” Miro matched his sister’s success at the X Games, also in the big-air event, allowing the pair to realise one of the dreams they conceived as children, when they would build homemade jumps.

Passions and idols

Tabanelli grew up in Corno alle Scale in the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines. Her parents are both mountain lovers and passed down their enthusiasm, as well as a strong creative fair, to their children. Her father, a graphic designer, had a major impact on her education: “His creativity infuenced me so much that I went to an art school for skiers, like my sister and brother.”

When not doing sports, Tabanelli pursues hobbies that allow her to keep her artistic talents honed. “I enjoy playing the piano [and making] abstract art,” she says. “I draw freestyle lines and curves to improve my technique, because I’d like to add a bit of style and movement to my landings, like Rell Harwood does and Alberto Tomba used to do.”

Tabanelli has a special relationship with Tomba, a fellow Bologna-born skier. Their meeting remains an unforgettable memory: “When I was little, he came to visit us in the mountains, which was fantastic. We couldn’t wait to see him. After my competitions, he wrote to me and encouraged me to keep going. He’s really inspired me. He’s my idol.”

Instagram: @flo_taba

1. Training playlist Rihanna

Love the Way You Lie

J Cole, No Role Modelz

Aaron Smith feat Luvli Dancin (Krono Remix)

2. Favourite movie

Mission: Impossible – the whole series

3. Favourite book

I’m Not Scared by Niccolò Ammaniti

4. Best trip Japan, for skiing and the food

5. Great love Bonsai

Snowboarder and filmmaker Elias Elhardt performs a layback on a ledge of snow whipped up by the wind.

“I’m very attached to this picture because it really captures the need for connection between the photographer, the athlete and the natural elements,” says the photo’s creator, Carlos Blanchard.

The rocky spurs of the Rocca Calascio in Abruzzo, Italy, have formed the backdrop of many of Blanchard’s photographs. “We spent a week there,” he explains, “and there was only one family in the whole place. Abruzzo surprised me: its landscapes and people are simply wonderful.”

Carlos Blanchard grew up in Zaragoza, Spain, but has always been drawn north towards the Pyrenees. He inherited his love for the mountains from his family, exploring this passion as both a snowboarder and a photographer. The Dolomites are one of his favourite landscapes, and the setting for many of his photos. In his work, nature is not merely a backdrop: by playing with light and contrasts, the snow, wind and rugged peaks come to life, becoming an active part of his visual narrative.

There’s an abundance of adrenaline-pumped images in snowboard photography. In this shot, Blanchard celebrates an ordinary moment: an athlete heading home from the slopes, the falling snow reflecting the photographer’s flash.

For Blanchard, this photo is “a dream come true, a reminder of how lucky I am to be able to work with some of the best athletes in this sport, and others”. The snowboarder immortalised in this jump is one of the photographer’s heroes, Gigi Rüf: “One of the greatest of all time.”

In Blanchard’s personal archives, there are many photos of him in the mountains with his father and grandfather. His grandfather was the previous owner of the Nikon F2 he uses to take most of his photographs, adding a vintage touch that’s part of what makes his style unique: “I use film because I think it makes images more authentic and emotional, and because that’s how I learned to take photographs.”

“That

a

A group of riders rests after a descent. “The composition isn’t perfect,” Blanchard admits, “but I like it because it captures an authentic moment of everyday life.”

Patience, slowness and meticulousness are three key elements in Carlos Blanchard’s photography. Working with film doesn’t provide instant feedback; this medium – which some might view as obsolete – requires careful attention and a detailed preparatory study of the weather conditions, the photo’s composition, the athletes, the way they move and perform tricks, and how they tackle and read the terrain. Blanchard’s relationship with the athletes is also crucial: in his photographs, he doesn’t stop at immortalising their sporting feats; he also seeks to capture their authenticity as people and snowboarders, focusing on moments that may appear insignificant but speak volumes about what it means to be part of the snowboarding community.

Carlos Blanchard is a Spanish photographer who specialises in analogue outdoor photography. He works with international brands and magazines including Arc’teryx, The Red Bulletin and Burton. Blanchard has created a number of individual visual projects – including Dreams and Dolore – and collaborated on many others, exploring the relationship between people, nature and sport.

In recent years, athletic training has undergone significant change: evolutions in technology, the latest scientific evidence and new professional roles are rewriting its methods. This has brought about indisputable progress while also presenting fresh challenges

Words Valerio Mammone

Over the last 10 years, the world of training has undergone an unprecedented revolution. Thanks to technological tools, groundbreaking scientific knowledge and new expert roles – all of them redefning the concept of performance – the daily training regimes of professional athletes have become increasingly targeted, personalised and supportive of their overall well-being.

“People used to think that training meant pushing yourself to the point of exhaustion. We now know that the quality of training is not proportional to the athletes’ strain.” These are the words of Matteo Artina, a performance manager whose career path demonstrates his intense love of sport. A coordinator at the Red Bull Athlete Performance Center (APC) –a multi-speciality centre in Thalgau, near Salzburg – Artina is also personal trainer to Sofa Goggia and the national Italian snowboarding team, as well as a university lecturer and supervisor, a weightlifting coach, and an expert in physical training for the Italian National Olympic Committee (CONI).

We interviewed the Italian several times over the last few months to fnd out more about his work, how it has changed over time, and the challenges that training shares with society as a whole: the shift to a hyper-technological and hyper-specialised era, and the emergence of a new generation of athletes with profoundly diferent traits to those who came before.

In the early 2000s, the use of technology in sport was still limited: GPS systems and the most cutting-edge sensors were costly and cumbersome. From 2015 onwards, the trend accelerated sharply with the development of sensors that were increasingly small, inexpensive and wearable, as well as machine learning and artifcial intelligence algorithms that made it possible to monitor an ever-growing number of indicators and gather a huge amount of data. Based

VISUALISATION, BREATHING, SELF-TALK: KATE O’KEEFFE, MENTAL TRAINING EXPERT AT THE APC, TELLS US HOW TO TURN ANXIETY INTO ENERGY

In what ways does mental training improve an athlete’s performance?

Mental training and physical training go hand in hand. Techniques such as visualisation, self-talk, mindful breathing and intentional mental rest improve concentration, reduce stress and promote recovery, helping athletes to give the best of themselves.

How has your discipline changed over the years?

Sports psychology used to focus on isolated actions and was often stigmatised as something that only ‘weak-minded’ people needed. Nowadays, research and practical application have turned mental coaching into a recognised discipline that’s key to improving performance.

How does a mental training expert help athletes to recover following an injury?

Injuries often come with fear, anxiety and dips in motivation. Recovery is based on gradual exposure, monitoring progress and rediscovering a sense of safety in movements. Fear is natural, but if it’s channelled correctly, it can shift from being an obstacle into becoming a tool.

Winter sports are stressful by nature. How do athletes deal with the tension?

Grounding techniques help athletes reconnect with the present moment and take back control in a fraction of a second. Mindful breathing, self-talk and simple reset gestures – a breath, a word – help athletes to maintain concentration and immediately recover from mistakes.

What role do mental routines or rituals play in their performance?

Little repeated habits send a signal to the brain that it’s time to act. For example, a snowboarder might visualise their first jump, or a biathlete might repeat a breathing pattern before firing a shot. These rituals create a sense of certainty and help to improve athletes’ control over their emotions.

Can you share a simple mental exercise for managing stress or improving concentration?

Try the ‘physiological sigh’:

1. Focus on your breathing.

2. Breathe in deeply through the nose. 3. Hold it for a moment, then breathe in again briefly to maximise the amount of air in your lungs.

4. Breathe out slowly through your mouth. Repeat this two or three times. This quick exercise reduces stress, lowers the heart rate and refocuses the attention. It’s useful in sports and also everyday life.

“Mental coaching used to be stigmatised. Now it plays a key role”

Kate O’Keeffe

TECHNOLOGY, DIALOGUE AND TEAM GAMES: CONOR

M c GOLDRICK, GLOBAL PERFORMANCE DIRECTOR AT THE APC, TAKES US INTO THE WORLD OF A HEAD OF PERFORMANCE

What does a performance expert actually do?

My job is to help athletes to display their abilities in critical moments. This doesn’t simply mean making someone faster or stronger; you’re creating the conditions for them to consistently demonstrate their skills under pressure.

What makes a training programme effective for athletes, particularly in winter sports?

A good training programme is able to balance the discipline’s particular requirements with the athletes’ personal qualities. In winter sports, that means developing explosive power, honing technical abilities at high speed and improving recovery so that athletes can take part in more races or events. Strength, technique and recovery work as a single system: with training, we develop the physical qualities that make it possible to execute athletic gestures. Recovery is key, as it guarantees constant improvement.

Why do some athletes reach a plateau in performance, and how can they overcome it?

Athletes can reach a plateau despite intense, high-level training. Progress is usually achieved by reviewing factors that are often overlooked, such as technology, lifestyle or recovery. For one of our athletes, concentrating on recovery made all

the difference: they changed their evening routine and sleep quality became a priority. In just a few months, their consistency and performance improved.

What role does technology play in shaping the performance of athletes at the APC?

Technology helps us to understand athletes. GPS systems, force plates and movement sensors track training load, biomechanics, recovery and preparation.

Integrating these tools gives us a clear picture, built on data. Technology guides our decisions with objective information, but the real impact comes from combining data with the experts’ opinions and the athletes’ feedback.

How does APC deal with the differences between individual athletes?

Each athlete is unique in terms of their physiology, their history with injuries, the stage they are at in their career, and competition requirements, meaning that each needs a highly personalised programme. For example, young athletes might require more intense training, while expert athletes need careful load management.

Are there any simple routines that are useful for most athletes?

A daily 10-to-15-minute routine is beneficial for almost all athletes, but consistency is more important than complexity, as it promotes recovery, reduces the risk of injury and keeps up the energy required for training and everyday life.

“My job is to allow athletes to consistently display their skill”

Conor McGoldrick

on this information, training routines have become personalised, ironed out to the last detail.

“Thanks to technology, we can now plan training sessions in a more organised way, and monitor them in real time,” Artina explains. ‘Even just an extra tenth of a second on the stopwatch is enough to show a sprinter is tired and the session should be stopped, even if the athlete doesn’t feel overtired.” The aim of technical staf is no longer to squeeze every ounce of efort out of athletes, but to ensure they have the right conditions to train for longer, consistently and without injury. This revolution was made possible by technological innovation, but it’s important to take care. “Technology,” warns Artina, “is like the sorceress Circe. It welcomes you in, gives you fgures and readings, makes you look intelligent and in control of the situation, but it’s up to us trainers to select the right information and judge whether the improvement of a certain fgure can really translate into improved performance.”

There’s another consideration: if sport were really only about data, competitions would be dull and predictable. “Training has become standardised: we all do the same thing because we all compare ourselves to the same benchmark. The diference is in the way all the indicators we try to improve interact with one another. I know athletes who, based on data, are weaker than their teammates in every way, yet they go on to win the World Cup. Theory and practice are two diferent things.”

Training may have changed but so has the concept of performance. Winning is no longer enough: every result is broken down, analysed and put back together with the athlete. “Trainers used to only analyse defeat. Now we analyse everything, because performance is made up of physical, technical, mental and nutritional building blocks, and our job is to understand how and to what extent each contributed to success or defeat.”

In many disciplines, athletes undergo technical and physical training at an extremely high level; so much so that we’ve reached a plateau. Artina explains that the point of diference lies in the dialogue between coach and athlete, as well as in mental preparation. “Athletes must be informed and aware of what they’re doing. When Sofa competes, the most important thing is that she believes in the quality of her training. This gives her the peace of mind to face bends and jumps at more than 120 kph, staying in the here and now, without getting distracted by tired legs.”

This paradigm shift has paved the way for a new professional role: head of performance, a position

Mario Omar Burke, a Barbadian sprinter who specialises in the 100m and 200m, undergoes biomechanical analysis while running at the APC

currently held by Artina at the Red Bull APC. A head of performance is not a super-coach who replaces all other specialists; instead, they work like the conductor of an orchestra, sharing out tasks and organising the work of a team comprising various experts. “If an athlete doesn’t have the right fuel, they can’t train. The fuel they need is prescribed by a nutritionist, who in turn bases their diet plan on the training programme set out by the technical coach. Each role supports all the others: a simple error in communication can throw everything of.”

The most obvious efect of this new athletic training regime, applied daily at the Red Bull APC, is the prevention of injuries. “We now know what really causes injury: a strength defcit, diferences between one limb and the other, poor hydration, and athletes’ neuromuscular fatigue.”

A generational shift

Athletes have changed just as much as training has. Over the last 20 years, society and family life have undergone signifcant changes, which have resulted in children leading a much more sedentary life and spending much less time playing freely in the street or at the park. From a very young age, children also tend to specialise in a single discipline. “Early specialisation is a precursor for injury,” Artina warns. “It’s no surprise that the American NCAA openly criticises it: the decision to dedicate oneself to a single discipline should only be made around the age of 14. Doing several sports makes a big diference because it enhances motor vocabulary, gets children used to reading diferent spaces and environments, develops orientation and builds strength on strength.”

The paradox is that, today, in a sporting world with access to extremely powerful technological tools, trainers must sometimes go back to basics. “Trainers have to be experts in movement, because today’s 25-year-olds need movement experts.” While the new generation works hard to build experience, today’s champions are displaying a completely different approach. “[Three-time world-champion Swiss alpine skier] Marc Odermatt does acrobatic jumps on fresh snow, and Sofa does downhill cycling in her free time to improve her refexes. The strongest athletes are those who have a broader motor vocabulary. That’s why I think that, today, we should have the courage to invest in courses that involve several sports – fun and stimulating activities in terms of motor skills – because that’s what an athlete’s physical and mental strength is based on.”

FROM FOCUS AND EXPLOSIVE STRENGTH TO POST-INJURY RECOVERY, IT ALL STARTS WITH PERSONALISED NUTRITION, EXPLAINS APC NUTRITION EXPERT STEPHEN SMITH

How does a personalised diet improve performance?

Personalised diets ensure that energy and macronutrients are aligned with the demands of training and competitions. They support recovery, improve athletes’ ability to adapt, protect the immune system, and ensure an adequate supply of energy. During a competition, tailored nutrition helps to avoid issues linked to blood sugar, while also preserving energy and clarity of mind.

Can you share an example of a time when nutrition made a difference to an athlete?

An endurance athlete was suffering energy dips and bloating halfway through races. Their calorie intake was sufficient, but their strategy during the race was wrong because they were avoiding carbohydratebased drinks due to previous bloodsugar problems. After six weeks of ‘intestinal training’, with a gradual increase in carbohydrates, the use of dual-source carbohydrates (glucose + fructose), a change in pre-race meals and a simplified diet plan, the athlete was able to maintain a constant energy level, with less discomfort and improved performance.

What’s the role of nutrition for athletes recovering from injury?

Food is essential for repairing body tissue, keeping inflammation at bay, and maintaining muscle mass when training is limited. The priorities are an evenly distributed protein intake, micronutrients for collagen synthesis (vitamin C, zinc, vitamin D), nutrient timing, and endurance training.

What impact does nutrition have on an individual’s concentration and stress?

Nutrition, as well as sleep, hydration and load management, helps to regulate stress. Stable glucose levels promote better concentration and decisionmaking capabilities.

What mistakes do athletes most often make?

The most frequent mistakes made by athletes are an insufficient energy intake, overly complex diet plans with untested products or supplements, and following generic advice instead of diet plans based on their own personal data.

Finally, do you have any tips for amateur skiers or winter sports athletes?

All you need is a simple routine:

1. A carbohydrate-rich breakfast containing a moderate amount of protein, two-to-three hours before exertion.

2. Carbohydrate-based snacks that are easily consumed between descents.

3. A regular intake of fluids: the cold reduces thirst but not our fluid intake requirements.

“Nutrition, along with sleep, regulates stress levels”

Stephen Smith

Specialist and overall champion in downhill and super-G events, Dominik Paris dominates speed with a unique combination of power, tactics and control

Some victories are truly deserving of the stories we tell about them. That’s certainly true of the titles won by Dominik Paris, one of the few skiers to have mastered all of the most coveted and respected downhill runs on the circuit. To speak with him is to dive into a unique universe made up of sheer cliffs, unquestionable speeds and courage in spades – essential qualities when pushing beyond your limits, striving to become one of the greatest downhill skiers of all time

“I love putting my body to the test”

rom the window of his house in Santa Valburga, Dominik Paris gazes out over the Ulten Valley. In this valley – quiet, private and resilient, one of the most remote in South Tyrol – ‘the Italian jet-man’ developed his identity, values, passion and unwavering determination. So much so that at the age of 36, with 19 victories to his name (the same number as Peter Müller), he’s the second most successful downhill skier ever, just behind Franz Klammer. Paris’ record is nothing short of impressive: a world title, a Super-G World Cup win and 50 podiums, with 24 World Cup victories – a competition in which he boasts another record. And these results were achieved without fear. “There’s respect for limits, yes, and that’s vitally important otherwise you risk getting hurt,” he says. “But if you’re afraid, you won’t enjoy yourself, and you’ll hold back. When I start feeling afraid, it‘ll mean it’s time to stop.”

the red bulletin: Do you remember your frst time on skis?

dominik paris: I was about three and a half when my dad – a ski instructor and huge fan of the sport – gave me and my brother the frst of many lessons. My mum, who didn’t ski, was compelled to start, too.

Was it love at frst descent?

Absolutely. I’ve been told that I no longer wanted to go to preschool, and ever since that moment all I’ve wanted to do is ski.

What fascinates you about the sport?

The jumps and turns at certain angles, the speed and technique, essential aspects for overcoming certain limits, for overcoming the things that seem impossible. Also, being able to have fun and put my body to the test. I’m a person who enjoys living.

You started competing at six years old and had several successes in your youth, but between the ages of 16 and 18 you distanced yourself from the slopes… Not exactly. My dream, my goal, of making it to the World Cup was always there, but I’d lost myself athletically. School couldn’t get me involved, less talented athletes were doing better than me, and if my friends called me to go out… well, I never said no.

So, when you were 18, you signed up to spend an entire summer as a herder in a Swiss mountain hut on the Splügen Pass… Those were tough, tiring months, but I trained consistently. Thanks to that experience, I matured and got my energy and enthusiasm back. I was ready to dedicate myself fully to skiing. Work and sport make you grow, and you’re born again.

Your results confrm this: within just two years you made the Italy national alpine ski team, and in 2011 you fnished second in Chamonix in downhill, a discipline that requires a lot of courage… And a bit of madness, let’s face it. But I realised straight away that this was my discipline, because in downhill it’s not just skill and technique that counts, but also tactics. You have to be able to read and interpret the terrain, choose the right path. In other words, you have to understand where and when to go faster to push yourself to the limit and win.

What’s the top speed you can reach on the slopes?

In the Canalino Sertorelli sliding section on the Stelvio slope in Bormio, it’s 152 kilometres per hour. It’s absolutely incredible! But it’s not the speed itself that’s the most challenging aspect; it’s managing to do it on an icy surface with no margin for error, possibly with bumps, really tight turns and very long jumps. Years of work and sacrifce are concentrated into a two-minute run.

How does a professional skier prepare for all this?

From April to August, before the season begins, I do extensive athletic training in the gym to prevent injuries and strengthen the skills that let me adapt to the various race terrains and new equipment, which require increasing levels of endurance. I always say that if you don’t work well in the summer –and if you’re not physically ft – the skis go with you, not you with the skis. The frst test I do on skis is in September, when we retreat for a month in the South American winter to fne-tune all the technical details and study the equipment.

How much equipment are we talking? The boots – the frst commandment in skiing – are handmade to respect the shape and feel of the foot. I try to fne-tune one pair per season, and I always keep some in reserve from previous seasons. Whereas for the skis themselves, I always test 12 downhill pairs and 10 super-G, from

which I eventually select two. Again, we keep some in reserve from previous years.

A skiman is a technician who specialises in maintaining ski equipment. Yours is Sepp Zanon. He’s the one responsible for the waxing, edges and bases of the skis, depending on the discipline and snow conditions. It’s a huge responsibility… There needs to be complete and utter trust between skier and skiman. If anyone makes the most mistakes, it’s me. [Laughs.]

Getting back to the downhills, you’ve won where it really counts: on the Streif in Kitzbühel, the Stelvio in Bormio, the Kandahar in Garmisch… Any left?

I’m still aiming for the Birds of Prey in Beaver Creek, and the Lauberhorn in Wengen – a beautiful, long, challenging slope requiring unique technical ability and fuidity.

While we’re on the subject of tempo and rhythm, are Rise of Voltage [the band he co-founded] still active?

Of course. We’re still playing and having fun. We’re still the same four friends from the valley, united by a passion for heavy metal. The rehearsal room is at my house, and I’m always the one screaming. [Laughs.] We used to only do covers, mostly Pantera.

What do you think of Sunday skiers?

Skis are like cars. Until a few years ago, you had to know how to drive to get behind the wheel. Today, cars can drive themselves. Likewise, when I was young, an adult would spend a week with an instructor before taking a chairlift alone. Today, with new equipment, you can learn to turn in half an hour, but not to ski, which makes everything more dangerous. More respect is needed, both for other people and for the mountains.

A unique athlete and national hero who brings a touch of madness to everything he does – here are some milestones from Dominik Paris’ career…

Dominik Paris will be one of the stars featured in Downhill Skiers: Ain’t No Mountain Steep Enough, a new documentary directed by Gerald Salmina. Filmed between 2024 and 2025, during the World Cup season and the World Championships in Saalbach-Hinterglemm, the show offers an inside look into the lives and challenges of the great speed skiers, including Marco Odermatt, Justin Murisier and Cyprien Sarrazin.

Dominik Paris was born in Merano on April 14, 1989, and grew up in the Ulten Valley. Thanks to his father, a ski instructor, ‘Domme’ quickly fell in love with the sport, and from his first race at six years old he knew skiing was something that he’d dedicate his life to. Paris’ two Trofeo Topolino victories marked a milestone in his skiing career, and he made his debut in FIS (International Ski and Snowboard Federation) competitions aged just 15. This photo, showing Paris as a child, is from his personal archive.

The first time in Bormio Back home, within less than two years, Domme had regained his rankings, joined the Italian national team and fulfilled his lifelong dream: to compete in the World Cup. In 2011, he achieved his first podium in downhill, in Chamonix, and on December 29, 2012, he won the first of six victories in the same discipline in Bormio. To this day, Paris remains the most successful downhill skier in history on the same track.

With his latest successes in the 2024/25 season, Paris has now reached 24 World Cup victories, a number that places him second in the list of Italian multiple winners, tied with the legend that is Gustav Thöni and just behind Alberto Tomba.

Between the ages of 16 and 18, Paris took a summer job to top up his weekly pocket money. But his work as a bricklayer, as well as evenings spent with friends, limited precious ski-training time, and the results stopped coming. To end this impasse, he decided to leave home and move to a Swiss mountain hut for three months, working as a herder. While there, Paris began training consistently again and regained his enthusiasm for his sport.

In 2013, ‘the Snow Jet’ – a nickname that underlines his sheer speed – won on the Streif in Kitzbühel and became the first Italian to do so two more times, once in 2017 and again in 2019. Also in 2019, at the World Championships in Åre, he took gold in the super-G, and at the end of the season he won the super-G in the World Cup and finished second in the downhill World Cup standings.

Seven hundred hours on skis, 300 at the firing range, 20,000 shots a year: Dorothea Wierer takes us through a typical year, revealing the programmes, tools and routines that have put her on top of the world

Dorothea Wierer was Italy’s frst-ever overall World Cup winner, the frst Italian (and only the third in the world) to achieve success in all seven competition formats, and the frst to bring biathlon to prime-time television for millions of viewers, turning a niche alpine discipline into a popular phenomenon.

This list of accolades alone would be enough to justify the titles ‘biathlon icon’ and ‘queen’, but Wierer has achieved far more. With her unique approach to competitions, especially in rife shooting, she has revolutionised biathlon itself, turning stops at the fring range into “Formula 1 pit stops” – in the words of her national teammate Tommaso Giacomel – and compelling her opponents to follow her into territory that, prior to her debut, remained unexplored.

Behind these results has always been meticulous daily work comprising hours on the slopes, at the fring range, at the gym and on a bike. Wierer’s training regime has changed over the years to adapt to her experience and age, becoming a system fne-tuned to the last millimetre.

When we discussed these methods in a long interview with Wierer, she answered with precision and wit – two qualities that have made her a household name as well as a one-of-a-kind athlete on the world stage.

the red bulletin: We read that you train a thousand hours a year: 700 cross-country skiing, 300 at the fring range. Is that true?

dorothea wierer: Yes! My team and I usually train twice a day, with one or two days’ rest every three weeks of exertion. We simulate the tiredness we’ll feel during the three weeks of the World Cup so that, when we compete, our bodies are used to it.

How is your training structured?

We start in May with basic, low-intensity physical exercise: running, roller skiing, a lot of gym sessions, loads of cycling, walking in the woods – and sessions at the fring range, obviously. Up to the end of June, shooting is kept separate from physical training, but from July we start a combined training regime, and the intensity increases. We do short but tough training sessions, some for 10 minutes at competition pace, others for 30 minutes, and some an hour long to get the body used to, well, sufering! This routine lasts from May to the end of October, then in November we head to Norway with our skis.

We’re curious, is there always snow in Norway in November?

Up to a few years ago, we trained on glaciers, but now it’s really difcult to plan training sessions because sometimes they’re in good shape and sometimes they’re really not.

Do you often train or compete on artifcial snow?

Yes, unfortunately. My technique works better on compacted snow, but increasingly often we encounter artifcial snow, which is powdery, so you sink into it. Now, even in Norway, ski resorts store snow from previous years to ensure they can host the World Cup and all the competitions take place.

Your trademark is speed and shooting precision – how many shots do you fre every year?

Lots, between 15,000 and 20,000.

And how do you work on precision? I work a lot on my position and movements. When you get to the fring range, you can’t think, you just have to do. To make your movements automatic, you need to work on your position and repeat the same gestures over and over again. You approach, you take up, you shoulder the rife, you lie down or adjust your standing position, you breathe, you aim, and you simulate the shot. And you do that thousands of times a year.

Your arrival at the range is one of the most critical and fascinating points of the race. You get there with a heart rate of 170 or 180, and in just a few seconds you have to be relaxed. How do you manage that? We train to get to the fring range as tired as possible so we can learn to halt our breathing for every shot. Once you’re in position, the trainer can see if your stomach or chest is moving, but you – the athlete – need to be selfaware, to be good at noticing the sensations your body is communicating. If you feel any tension, you need to be able to get rid of it: your body changes from year to year, and sometimes you just need to shave a few millimetres of the rife’s butt plate so it’s a better ft. Sometimes it’s all in the mind: if you made a mistake in the last competition, you change your butt plate just so you can tell yourself, “I’ve done something to improve.”

“I’m still afraid of failure, but feeling pressure helps me give 110 per cent”

Weather conditions are often an unknown – is there any specifc training you do in case of strong winds or low visibility? I train outdoors in all weather – rain, wind, snow, extreme cold or heat – using up to 50 diferent types of skis, depending on weather conditions.

You’ll be 36 in April, with almost 20 years of top-level training behind you. Has your regime changed over the years?

Yes, a lot. When I was younger, when I was frst competing in the World Cup, there were three types of training: low, medium and high intensity. On medium-intensity days, I often did high-intensity training because I wasn’t monitored as precisely as I am now. We always trained… I wouldn’t say at full throttle, but most of the training sessions were a real struggle. [Laughs.] Over time, trainers got more information about how to structure regimes. In the last few years, I’ve started to train less, but in a more targeted way, paying more attention to rest, which is crucial at my age.

Is there anything you did at the start of your career that turned out to be a big mistake?

Oh, yes! When I was younger, we practically only drank water. [Whereas] today, thanks to studies on integration, we know that drinking carbohydrates during competitions makes a huge diference – I can see that clearly. I don’t know how I managed without it for so many years.

How do you feel about competing? Are you anxious or calm when you race? I’ve always been afraid of failure, and I still feel stressed and tense before a competition.

How do you manage your anxiety?

I don’t try to manage it – I just go for it! I see it as something negative, but I think it helps me feel the pressure that makes me give 110 per cent.

What is the moment that scares you the most?

Perhaps shooting. The last fring range is always the most critical moment, where you’re most afraid of making a mistake. For a while, I always messed up the last shot.

And how did you get over that?

I started shooting at the opposite target to break the pattern.

Biathlon is a sport where you often train in mixed groups – who has been your mentor?

Over the course of my career, I’ve been lucky enough to meet lots of important people, even when I was a child. When I started out, I was a bit lazy: I got good results, but I preferred hanging out with my friends to putting the efort in. My trainers found the right way to motivate me by challenging me. When there’s a challenge, I spring into action. That’s still the case today.

On the subject of challenges, you’ve recently talked about retiring from your sport, which is perhaps the most difcult challenge you’ll have to face. How does that make you feel?

It scares me a bit, because biathlon has been my whole life. When it happens, though, I’ll try not to show those emotions. Just like with every victory or defeat, I hope I’ll be able to keep my feelings to myself.

Instagram: @dorothea_wierer

Wierer’s ECG under stress, pictured below, shows her heart rate peaking before she gets to the firing range, then her heartbeats rapidly decreasing. She achieves this with her breathing at the key moment when she aims at the target.

To hone her shooting precision and perform her gestures automatically, Wierer repeats the same sequence hundreds of times, from entering the firing range to simulating the shot

Arrival at the range

The moment that makes all the difference This graph shows a training session with four series of shots: two prone and two standing. In this exercise, Wierer’s heart rate reaches 178bpm in the fourth sequence

“I always messed up the last shot, so to break the pattern I started shooting at the opposite target”

“When you get to the firing range, you can’t think, you just have to do”

At the gym, Wierer performs two strength-training sessions a week – crucial for unleashing more power during her final sprints

In the early 1900s, when skiing gradually began to spread from Norway to Central Europe, it became clear that more stable bindings were needed on the Alps than on the Nordic flatlands, where the most popular sport was cross-country skiing – an activity that caused much less strain on equipment than its alpine cousin.

One of the first solutions was the so-called Kandahar model, with steel clips, leather straps and a metal cable (pictured: the first Tyrolia model from 1949). While the spring-loaded system ensured basic protection from the most violent falls, it was still a far cry from the safety offered by modern bindings.

From handmade objects to high-tech masterpieces: how ski equipment has evolved from the 1930s to today