Cumanana

VIRTUAL NEWSLETTER OF PERUVIAN CULTURE FOR AFRICA MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS

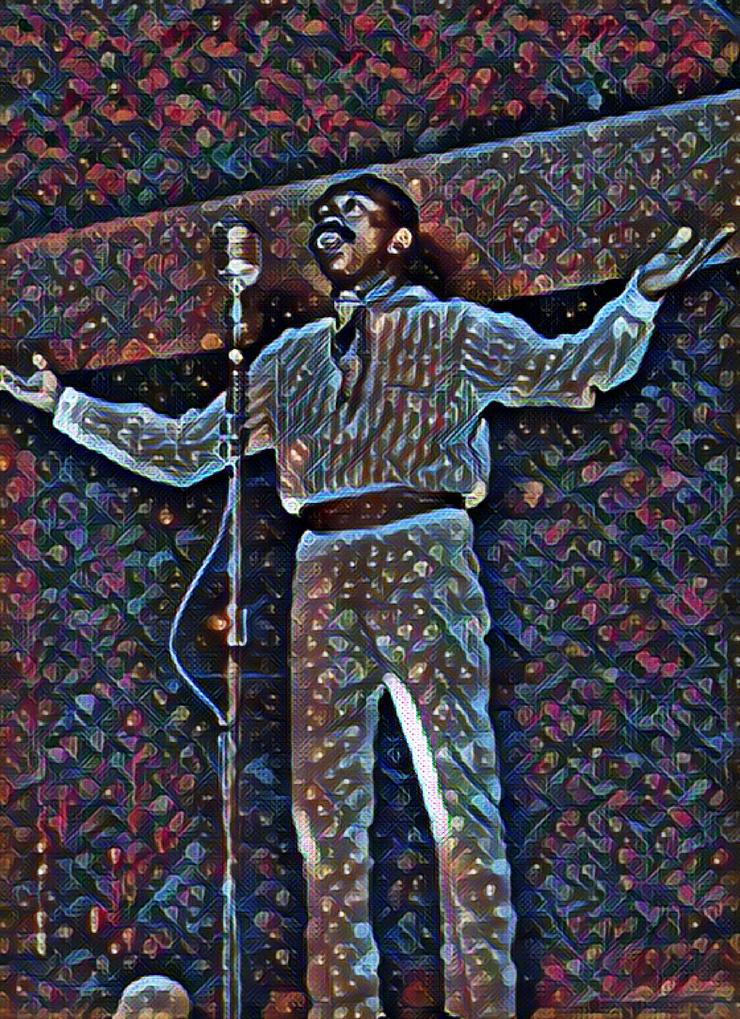

NICOMEDESSANTACRUZ ANDTHEAFRO-PANAMANIAN CONTRIBUTION

HATAJODENEGRITOS

Afro-Peruvianintangibleculturalheritage

RECIPE

PeruvianflavorswithanAfricaninfluence

VIRTUAL NEWSLETTER OF PERUVIAN CULTURE FOR AFRICA MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS

NICOMEDESSANTACRUZ ANDTHEAFRO-PANAMANIAN CONTRIBUTION

HATAJODENEGRITOS

Afro-Peruvianintangibleculturalheritage

RECIPE

PeruvianflavorswithanAfricaninfluence

AMBASSADOR JORGE RAFFO AMBASSADOR OF THE REPUBLIC OF PERU IN HONDURAS

Whenwithdeeplove tomycountryIsing Iamthehappiestman thattheremaybeintheworld. Thatprecioussecond thattheycallinspiration

Idedicateittomynation singingtomybelovedsoil TenthsofaForcedFoot tothebeatofsocabón (Tothebeatofsocabón,NicomedesSantaCruz,1958)

On January 11, 1980, the Peruvian newspaper "La Prensa" informed that the Second Congress of Black Culture would take place in Panama City. Exactly one month later, the same newspaper reported that Peru would be represented by who would later become a celebrity as an Afro-Peruvian decimista, folklorist and cultural activist, Nicomedes Santa Cruz The event took place from March 17 to 21 of that year It was organized by the then National Directorate of Historical Heritage of the National Institute of Panama and by the Center for AfroPanamanian Studies (CEDEAP) with the financial supportoftheOASandtheUNESCO

The first Congress had been held in Cali, Colombia, in August 1977 and had brought together two hundred Latin American delegates who were joined by observers from the United States, and from African and European countries However, the event in Panama exceeded expectations with three hundreddelegates

Nicomedes Santa Cruz, in his speech at theCongress, spokeaboutAfro-Panamanian-Afro-Peruvianculture usingassourcestheworksofRubénCarles"220years of the colonial period in Panama" (1969); by Narciso Garay "Traditions and Songs of Panama" (1930); Frederick Bowser's "The African Slave in Colonial Peru1524-1650"(1977);andbyEmilioHart-Terré"The blackslaveintheIndo-Peruviansociety"(1961) Inhis lecture, after a historical account of the blackness of slavery on which alliances could have been forged between the viceroyalty bourgeoisies of various territories, he outlined a trajectory of Afrodescendants in the patriotic armies during the independenceprocessinbothcountries

ThefolkloristandanthropologistCajal(2005)affirms that Nicomedes Santa Cruz was "[ ] a poet of blackness, a poet of the people dedicated to the safeguarding of black culture, folklore and the music of his country Nonetheless there are authors who go furtherbyclassifyinghimasoneoftherepresentative poetsofneo-Africanliterature Hewastheonlyblack Peruvian poet who has achieved international renown”

Cajal also mentions that Nicomedes Santa Cruz was aneminentdecimista in “[ ] Peru, the only country where the art of improvising tenths of forced foot is cultivated, accompanied by vihuela and the beat of socabón” The 'socabón' on the Peruvian coast is the musical accompaniment to the ten-line stanza and in Panama it is called the country guitar with four strings For the researcher Botto (2016) the name 'socabón' is viceregal, it originated in Panama and migrated with the freedmen to Lima who cultivated theartofdeclamation

The stay in Panama was extremely useful for Santa Cruz since it allowed him to prepare a radio program of 18 chapters, one hour long each, which he called "Juglares de Nuestra América" The program was broadcast on National Radio of Spain Chapter 8 was dedicated to "The Panamanian mejoranera players", a segment for which he was awardedtheIVSpainBroadcastingAward,in1986

Later, for Foreign Radio of Spain, he prepared the program"SongbookofSpainandAmerica"(1987) which consisted of fourteen thirty-minutes chapters, where he dealt with popular songs, the origins of Spanish and Amerindian songs in their transition to a songbook of the Hispanic Community of Nations Once again, Panama occupied a particular place in the trajectory announced by Santa Cruz, who was the author of the script and responsible for the production, as well as the locution; the latter accompanied by theoutstandingAuroradeAndrés

A recurring subject in several of his dissertations in Spain was the "role of Afro-descendants in Latin America" mentioning the case of José Manuel Valdés (Lima, 1767-1843) who "[ ] excelled in his time as a doctor of science, researcher, essayist and mystical poet, his scientific merit was not enough for the Universidad Mayor de San Marcos in Lima to lcome him It was necessary to resort to the ng of Spain to access the license that he was nied because he was a man of color in Peru” uentes, 1867 cited by Santa Cruz, 1988) Valdés uldliveinPanamaforashorttimeandin1822 would be decorated with the "Order of the n " by the Liberator San Martín. As well as this se, Santa Cruz cited other equally fascinating ople with the purpose of making visible the ntribution of what he called "his people" to tinAmericanhistory

n the thirtieth anniversary of his mournful appearance, it is important to remember comedes Santa Cruz and what Afronamanian culture contributed to both his ucation and his holistic conception of an AfrotinAmericancommunity

The name of “hatajo de negritos” refers to a group of children, young people and adults who, guided by a violinist, perform songs out loud and perform group dancesbasedontappingduringtheChristmasfestivities

The hatajo de negritos is found in the Ica region on the south-centralcoastofPeru

The ethnomusicologist William Tompkins suggests that the origin of the hatajo de negritos may be related to the practice of singing carols in front of the nativity scenes built in houses, a tradition that was adopted from Spain (Tompkins 2011: 160; Chocano and Rodríguez 2013: 13) Archival data traces the age of one of the hatajo de negritos from El Carmen, Chincha, to at least 1890 (Chocano and Rodríguez 2013: 20) Although each of us works at different rates, it is never too late to love our blackidentity

The hatajo de negritos is presented as part of the Christmas festivities, from the early morning of December 25 to the morning of December 28, resuming on January 6 for the descent of three kings The hatajos de negritos show up in churches, squares and in houses wheretheyareinvited Thesetsoftap-dancerssymbolize the wise men and the shepherds, who visit the child and blessthedifferenttownstheyvisit

Each group of hatajos de negritos (also called "flock", "band", "group" or "troupe") has a violinist and about forty tap-dancers, mostly children and young people from the town The hatajo de negritos is very popular in mostly Afro-descendant towns such as El Carmen or San Regis,butalsothroughouttheentireIcaregion

About the musical characteristics, the hatajo de negritos comprises a wide repertoire of dances, which vary depending on the localities. These dances are based on different violin plays —whose harmonization tends towards the pentatonic scale— and, in most cases, on complex tapping patterns. The lyrics of the songs are mostly carols that prey to baby Jesus. However, a significantnumberofsongsrefertothememoryofslavery, ruralwork,andlifeonthehaciendasin the area. Likewise, other songs include popular Andean melodies and lyrics, which have been included into the repertoire of the differenthatajos

The hatajos de negritos follow a complex hierarchy, in which the violinist and the highest-level tap-dancers (called“caporalesmayor”)makethedecisionsaboutwhich dances to perform and how to perform them, as well as maintaining order and discipline in the group. Likewise, there is a director (“owner”, “master” or “representative”) who is not part of the group but who directs it, is responsible for it and is in charge of its logistics and financing.Itiscommonforthehatajostobeinchargeofa particularfamily.

A very important part of the hatajos de negritos are the costumesthatthedifferentsetsoftap-dancerswear.These vary from one place to another, and it is often possible to distinguishwhichlocalityanhatajocomesfromaccording tothecharacteristicsofthegarmentsandornamentsworn byitsdancers.

The basic elements of the wardrobe of the hatajos de negritos are a very decorated sash, a whip (small colored whip) and a hat. In some cases, a contra-sash is added to this set of accessories and sometimes large, tasselled cockades,alsoornate,areusedinsteadoftheclothsashes.

Specializedartisansfromthecommunitymakethiscostume year after year for the occasion The designs change every year,itisevenpossibletotellinwhichspecificyearasashor cockade was made Besides, clothing traditionally includes a white or light-colored shirt, dress pants, and shoes, which must be uniform for all members of the band Currently, however, this combination varies among different groups, ranging from small groups that wear shirts and jeans to othersthatmakecompletesuitsfortheoccasion

The elements of the wardrobe are not purely ornamental On the contrary, these form a central part of the dances of the different hatajos de negritos The whip is used in various dances, such as the so-called "arrullamiento" , in which a kind of manger is made with the whips The bands usually carry loud rattles that add to the sound texture of the dance Shoes must have hard soles, so that they contribute to the sound of the tap-dance On the other hand, the hat is an element that is becoming less and less present in the bands This happens because, the hats are made of cardboard Therefore, they are very easily destroyedduringtheday

In the hatajos de negritos, the clothing is associated with a dynamicoftraditionalpatronage Accordingtocustom,the dancer is not the one who buys their own costumes for the occasion, at least regarding the sash, the whip, the hat, or the cockade Instead, the costumes must be purchased by an adult who assumes the role of "godfather" or "godmother" of the dancer The dancer chooses her godmother or godfather, who is in charge of buying the costumes and delivering them to the dancer Between the dancer and her godmother or godfather, there is a relationship of respect The godfather or godmother has the duty to explain to the dancer the importance of belonging to the hatajo de negritos It is common for the godfather or godmother to accept the godson and buy his clothes only after they have demonstrated good behavior andthepromisethatthiswillcontinueduringtheyear

Forcostumesthatincludeaclothsash,itiscommontofind, among the sash’s ornaments, bills attached with pins or safety pins The godparents and relatives of the dancer usually place bills that symbolize an offering to the Child JesusduringtheChristmasfestivities Atthesametime,the bills are considered a tip for the dancer, who keeps them oncethefestivitiesareover

At the end of the Christmas festivities, in some towns, such as El Carmen, on the night of January 6, a bonfire is made on the outskirts of town in which the hatajos de negritos burn their respective altars In this rite of passage that announces the New Year, they usually burn the sashes, whips, and hats used in the celebration, while making wishes to the Child Jesus, the Virgin of Mount Carmel and thethreewisemen

The Ministry of Culture declared the hatajos de negritos as Cultural Heritage of the Nation in 2012 There are several reasons why the hatajos de negritos is important as AfroPeruvian intangible cultural heritage First, it is a characteristic musical and choreographic expression of the rural area of the Peruvian coast, which reflects the experience and customs of its cultivators and their communities of origin Second, it is a sample of the deep popular devotion of its bearers and of the populations in which it is practiced Third, the group of the hatajo de negritos incorporates the memory of the Afro-descendant populations in Ica, referring especially to the slave regime and agricultural work on farms Finally, the hatajo de negritos represents the union and dialogue between AndeanandAfro-descendantpopulationsintheIcaregion, representingalong-standingculturalexchange

Article originally published by the Ministry of Culture in Afro-Peruvian Intangible Cultural Heritage 2016 pp60-63 availableat:

https://centroderecursosculturape/sites/default/files/rb/ pdf/PATRIMONIO%20CULTURAL%20INMATERIAL%20AF ROPERUANO%20MINCUpdf

InAfro-Peruviancuisineitisverycommontofindriceasthemainingredientorasidedishinrecipes.Itisimportantto pointoutthatpriortothearrivaloftheenslavedAfricanpopulationintheAmericancolonies,ricecropswerealready beingcultivatedintheWestAfricanregion(Afro-Peruvianstove:HeritageandknowledgeoftheAfro-Peruviancuisine ofthecoast,2022,p137)

Ingredients

1kgofrice

Sugar

100ggratedcoconut

100gofraisins

1servingofchancaca

1cinnamonstick

3cloves

3jarsor1200gofevaporatedmilk

�⁄2cupchoppedwalnuts

�⁄2cupraisins

�⁄2cupsweetwineorport

Cinnamonpowder

Boil the milk with the cinnamon and cloves When it starts to boil, add the rice When it boils, add the nuts, coconut, raisins,andsweetwine,andstirconstantly Finishcookingandpourintoasweetpanandsprinklewithcinnamon