Cumanana

VIRTUAL BULLETIN OF PERUVIAN CULTURE FOR AFRICA

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS OF PERU

SÃO MIGUEL FORTRESS

VIRTUAL BULLETIN OF PERUVIAN CULTURE FOR AFRICA

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS OF PERU

SÃO MIGUEL FORTRESS

40 YEARS OF THE ESTABLISHMENT OF DIPLOMATIC RELATIONS WITH ANGOLA

FROM CHANCAY TO THE INDIAN OCEAN

CHICKEN MUAMBA

40th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations with Angola.

Minister Mario Bustamante Reátegui, Head of Chancery of the Embassy of Peru in South Africa

Queen Nzinga Mbande: A Legacy of Resilience and Leadership

Embassy of Angola in Brazil

Forty Years of South American-African Brotherhood: the establishment of diplomatic relations between Peru and Angola (19852025).

Second Secretary María del Carmen Fuentes Dávila Fernández

Cultural heritage and tourism potential between Peru and Angola: one view, two realities

Third Secretary Ítalo Guillermo Loayza Román

SPECIAL SECTION: EXPANDING AFRICANNESS

From Chancay to the Indian Ocean

Ambassador Jorge Raffo Carbajal, Director General of Peru for Africa, the Middle East and the Gulf Countries

The Bells and the María Angola Canal in Peru

Second Secretary Antonio José Chang Huayanca

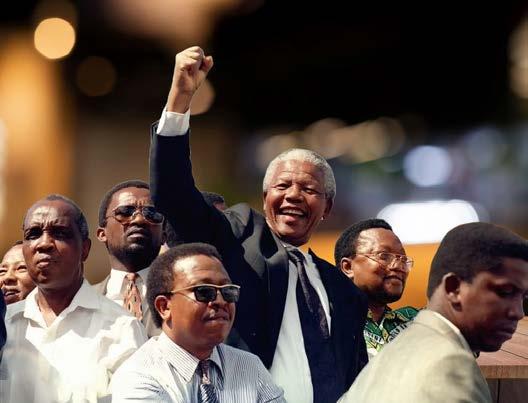

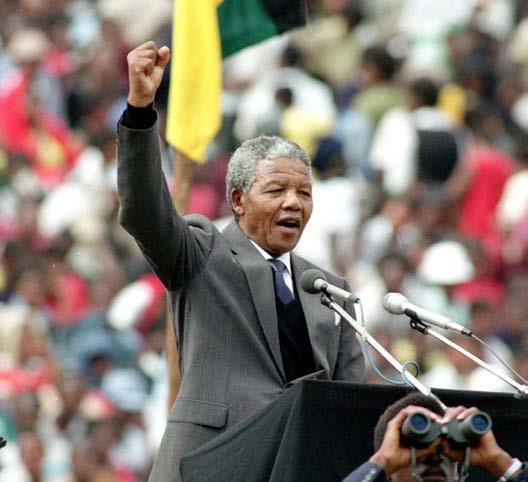

Nelson Mandela's Portrait

José Yepez Castro, Counselor of the Diplomatic Service of Peru

Chicken Muamba

Mario BustaMante reátegui

Minister in Peru’s DiPloMatic service

HeaD of cHancery of tHe eMBassy of Peru in soutH africa

On September 6, 1985, in Luanda, the capital of Angola, the then Peruvian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Allan Wagner, together with his Angolan counterpart, Afonso Van-Dúnem ‘Mbinda’, signed a Joint Communiqué on behalf of their respective governments, by which, in addition to developing ties of friendship and broad cooperation, they decided to establish diplomatic relations in accordance with the principles of international law— in particular the sovereign equality of States, mutual respect for their sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity, the self-determination of peoples, non-interference in the internal affairs of other States, respect for obligations arising from international treaties, and the peaceful settlement of disputes—also expressing their rejection of colonialism, apartheid and all forms of racial discrimination.” National Archive of Treaties. (1985).

Although this marks the formal starting point of bilateral relations, their origins can be traced back to the seventeenth century, when Angola was a Portuguese colony and Peru formed part of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Although some historical references mention that the authorship of the painter of the sacred image of the Lord of Miracles, the "Cristo Moreno", is disputed, others indicate that it was the Angolan slave Pedro Dalcón, known as Benito, who painted the image of Christ crucified on an adobe wall. The historian Raúl Porras Barrenechea dates this to 1651. The painting survived the earthquake of November 13, 1655, which destroyed Lima and Callao, giving rise to widespread devotion to the image , and one of the most representative and multitudinous processions in the Catholic world that is also celebrated in several countries of the world.

More than 300 years later and 40 years after the establishment of diplomatic relations, we have begun a new stage in the bilateral relationship with the holding of the First Meeting of the Political Consultation Mechanism at the level of deputy foreign ministers. 1

September 6, 2025, will mark the 40th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Peru and Angola. During this year, activities have been carried out that have strengthened the bilateral relationship.

Ambassador Javier Augusto presented his credentials on February 26, 2025, as non-resident ambassador to the Republic of Angola, resident in Pretoria, to that country’s President, João Manuel Gonçalves Lourenço, thus becoming the first Peruvian representative accredited to the Angolan government.

Two days earlier, on February 24, he presented copies of his letters of credence to the Secretary of State for International Cooperation and Angolan Communities, Ambassador Domingos Custódio Vieira Lopes.

Among the issues that were discussed, Ambassador Augusto indicated that it would be a good opportunity to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations with the holding of the First Meeting of the Political Consultation Mechanism in Lima, both the President and the Secretary expressed their full willingness for officials of their government to attend that inaugural meeting.

On April 25, 2022, a Memorandum of Understanding for the establishment of Political Consultations between Peru and Angola was signed in Lima by the then Foreign Minister César Landa and the Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ambassador Ana Rosa Valdivieso and Ambassador Florencio de Almeida, Ambassador of Angola to Peru with residence in Brazil, giving a new content to the bilateral relationship.

The presentation of credentials of the first Peruvian ambassador to Angola in February 2025 prompted the holding of the First Meeting of the Political Consultation Mechanism.

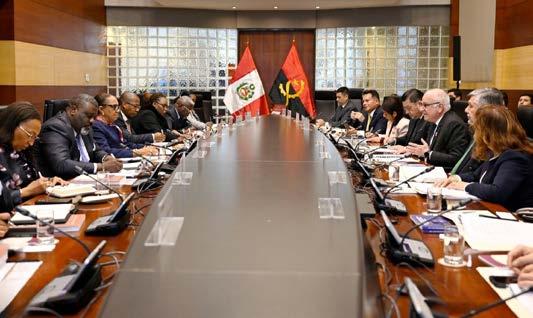

The inaugural meeting of the Political Consultation Mechanism was held in Lima on July 9, 2025, and was chaired by the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Peru, Ambassador Félix Denegri Boza, and the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs of Angola, Ambassador Esmeralda Bravo Conde da Silva Mendonça.

Source: Government of Peru.

An account of the bilateral relationship was made, reaffirming the mutual commitment to the strengthening of political dialogue, technical cooperation and more active bilateral trade, highlighting the coincidences in the defence of the rule of law and the promotion of democracy, peace and international security, such as cooperation in the areas of agriculture, energy and mining.

In 1988, Peru and Angola took an initial step to assess the possibilities of bilateral cooperation, including economic, scientific, technical, cultural and commercial cooperation, and a Memorandum of Understanding was signed. At that time, Angola's interest was to receive "cooperation from the Peruvian side in the areas of civil aviation, industrial development and hydroelectric energy production in rural areas."

Years later, in 2019, in collaboration with FAO, both countries in addition to Honduras and Uruguay participated in the project "Development of Strategies for the inclusion of fish consumption in school feeding."

On this occasion, a proposal for an inter-institutional cooperation agreement was reviewed, which could be the framework for the implementation of SouthSouth and triangular cooperation projects, through the Camões Institute of Portugal, with Angola expressing interest in areas of export and investment promotion.

Based on the coordination carried out by the Embassy of Peru in Brazil and Angola’s embassy in that country, which is concurrently accredited to Peru, agreed to issue a commemorative postage stamp in memory

of the 40 years of diplomatic relations between our countries, as well as stamp issues with Senegal and Tanzania, with the decisive support of SERPOST.

Source: SERPOST

Regarding the Angola stamp issue, Peru will be represented by the Taruca (Hippocamelus antisensis), and Angola by the Giant sable antelope (Hippotragus niger variani), which is also that country’s national symbol. The conservation status of both species is categorized as threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN); the Taruca is classified as Vulnerable and the Giant sable antelope as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

This commemorative stamp is expected to be presented on October 21, 2025, in the week of the XVI Peruvian African Friendship Day.

Other cultural activities planned this year promoted by the General Directorate of Africa, the Middle East and Gulf Countries of the Peruvian Foreign Ministry is the Angolan participation in the 49th edition of the cultural bulletin "Cumanana", which is dedicated to the 40th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations, as well as its intervention in the XVI edition of the Peruvian-African Friendship Day, to be celebrated on October 20 and at the X African Film Festival, that same month.

It was agreed to sign the Agreement between the Republic of Peru and the Republic of Angola on visa exemption for holders of diplomatic, special, service and official passports, which is expected to be signed on the margins of the 80th United Nations General Assembly in September.

In addition, there is a shared interest in opening honorary consulates in both Lima and Luanda, which reflects the excellent level of bilateral relations between our countries and the commitment to strengthen our bilateral relationship.

Angola's interest in obtaining collaboration from the Diplomatic Academy of Peru is not new. Article 8 of the Memorandum of Understanding of December 1988 mentions the following:

"8.- Likewise, the delegation of the People's Republic of Angola expressed its wish that the Diplomatic Academy of Peru could receive Angolan scholars to follow the course of applicants taught in that study center. The Peruvian Party took due note of this request and stated that it would evaluate this possibility and that it would transmit to the authorities of the People's Republic of Angola the requirements for admission to the Diplomatic Academy of Peru."

During the First Meeting of the Political Consultation Mechanism, it was proposed to hold virtual conferences on issues related to the participation of both countries as non-permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, conflicts in Central Africa, economic integration mechanisms, among others.

The Venâncio de Moura diplomatic academy is recently created, inaugurated in 2020 and is the training center for Angolan diplomats, so there is the possibility of signing a memorandum of understanding between both centers of study to promote its development.

The long-standing Angolan request for the Diplomatic Academy of Peru to receive scholars from that country should also be considered.

The fight against drugs is a concern shared by both countries and given that Angola has been strengthening its control and response mechanisms against this scourge, a cooperation agreement could be signed on counter-narcotics, allowing Angola to draw on Peru’s experience.

Bilateral trade is currently limited and in recent years has largely reflected fluctuations in oil imports. Angola is Africa's second-largest oil producer after Nigeria.

Source: Prepared by the Directorate of Trade Promotion of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs based on information from SUNAT (2025*: January - May).

In addition, according to the detail of exporting and importing companies to Angola, in 2024 only two exporting and importing companies were listed, while in the period from January to May 2025 four exporting companies are registered, without any imports from Angola having been registered.

In 2024, Angola was Peru’s 189th trading partner and 40th within Africa.

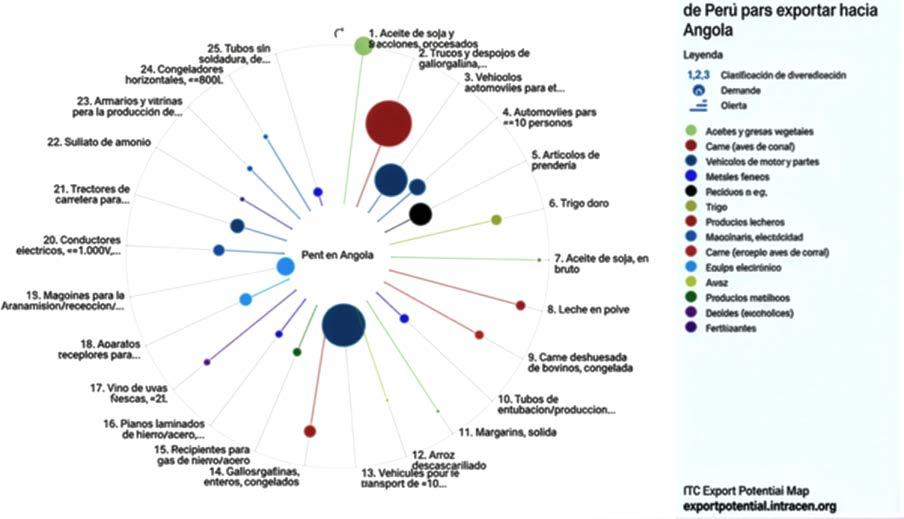

Source: International Trade Center (ITC)

According to the International Trade Center (ITC), the products with the greatest export potential from Peru to Angola by 2029 are beans, dried and shelled; ethyl alcohol, undenatured, >=80% alcohol; and, nets of knotted fishing nets, made of artificial textile. Lacquers, colorants and preparations are the product exported by Peru with the greatest supply capacity. Palm oils and processed fractions is the product that faces the greatest potential demand in Angola.

Source: International Trade Center (ITC)

Similarly, Peru's best diversification options in the Angolan market are soybean oil and fractions, processed; pieces and offal of rooster/hen, frozen. Peru has an easier time reaching soybean oils, in crude form; Frozen rooster/hen pieces and offal is the product with the highest demand potential in Angola.

One of the ways in which the modest commercial exchange could be increased is the holding of virtual seminars in order to bring together the business associations of both countries. It is not ruled out that more Angolan oil will be bought in the future, given the vast reserves it possesses. There are untapped opportunities that could increase trade flow.

According to academics Hassan Noorali, Colin Flint y Seyyed Abbas Ahmadi

“although ports may seem to play a primarily economic role on a local scale, they are also important in global and geopolitical processes. Ports connect the geographical areas of land and sea as geographical sites with the dual function of economic gateways and geostrategic projection nodes.” 6

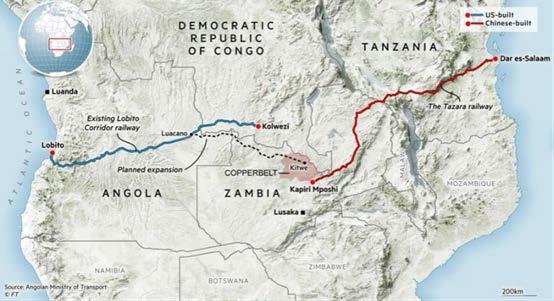

The Lobito Corridor and port are major infrastructure that will transport strategic minerals from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia to the coasts of Angola, opening new access routes from Central and Southern Africa to the Atlantic Ocean, being an alternative route to the one currently carried out through the Indian Ocean.

Source: Angolan Ministry of Transport, in Financial Times

Peru can learn from the Angolan port experience in terms of knowledge of the logistics chain that includes services to transport companies such as shipping companies, railways, and road transport, as well as ship maintenance services, among others, even more so when there is the possibility of generating a Chancay-Santos bioceanic corridor, linking the Pacific coasts with the Atlantic that would transform regional logistics. strengthening trade between South America and Asia and generating

Since Peru’s 2024–2030 Strategic Plan for Africa states ‘Strengthen Peru’s presence in Africa, with particular attention to the political and trade spheres, with the aim of achieving better positioning and integration, diversifying relations, and enhancing Peru’s insertion into international markets…’, it is advisable to reinforce ties of friendship and cooperation with countries that have shown interest in consolidating this relationship. The fact that Angola has appointed concurrent ambassadors from Brazil several years ago demonstrates this.

Angola is also important because it shares Peru’s commitments to the rule of law, democracy and international peace; free trade; food security; and the

important economic and social benefits.

A twinning of cities could also be proposed between Lobitos and Chancay, cities that will face common challenges in terms of social and environmental impacts, urban development, security and control, among others.

defense of multilateralism—while facing similar challenges such as poverty, environmental degradation, corruption and illicit drug trafficking.

With regard to Angola's international participation, the country is currently president of the African Union and has recently been president of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), organizations in which Peru is interested in becoming a member. Angola would be a great partner in our intentions to strengthen relations with the African continent.

It is suggested that as part of this strengthening of Peru's diplomatic relations with African countries, the visit of the highest Peruvian diplomatic authorities should be considered at least once every five years.

More than 13 years after a Peruvian foreign minister visited Africa – the last one was Rafael Rongagliolo, in 2012, although it was to promote the III South

References

America-Arab Countries Summit (ASPA), which was being held in our country – it is time, more than opportune, to relaunch our gaze towards this continent and what better way to do it than in Southern Africa. For the time being, the Foreign Minister of Angola has invited the Foreign Minister of Peru to make a visit to his country, which we hope can take place in the near future.

National Archive of Treaties. (1985). Joint Communiqué between Peru and Angola on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations (B-1574). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Peru.

https://apps.rree.gob.pe/portal/webtratados.nsf/Tratados_Bilateral.xsp?action=openDocument&documentId=48DA

Embassy of Peru in South Africa. (2025, February 24). [Photo]. Presentation of the copy of the credentials of the ambassador of Peru in Angola

Financial Times. (s.f.).

Ministry of Transport of Angola. Map of the Lobito corridor.

Government of Peru. (2025, July 9). Important aspects of the First Meeting of the Peru-Angola Mechanism Political Consultation [Photo].

Noorali, H., Flint, C., & Ahmadi, S. A. (2023). Geopolitical significance of ports: Gateways and nodes. [Academic article cited in the text].

Porras Barrenechea, R. (1951). Lima: Fondo Editorial. The Christ of Miracles: Tradition and devotion in colonial Lima.

Presidency of Angola. (2025, February 26). Presentation of the credentials of the Ambassador of Peru to President João Lourenço [Photo].

SERPOST. (2025). Issuance of commemorative stamps Peru–Angola, Senegal and Tanzania [Institutional statement].

SUNAT. (2025).

Peru–Angola Foreign Trade Statistics (January–May 2025).

Trade Promotion of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Peru.

Notes

1. In "El Comercio", The story of the slave who painted the image of the lord of miracles

https://elcomercio.pe/respuestas/quien/quien-fue-el-esclavo-que-pinto-la-imagen-del-senor-de-los-milagros-esta-es-su-historia-octubre-2023-tdpe-noticia/.

Retrieved August 5, 2025.

2. Angola, for its part, has had a greater diplomatic presence in Peru.

3. B-1582. Memorandum of Understanding between the Republic of Peru and the Republic of Angola (annex I delegation and annex II, draft technical cooperation programme). December 9, 1988. In National Archives of Treaties ambassador Juan Miguel Bákula Patiño. Taken

4. Extensive information in:

Elaboración de Estrategias para la Inclusión del Consumo de Pescado en la alimentación Escolar | INFOPESCA

5. In: where you can also see the breakdown for each item. Export Potential Map

6. Port power: Towards a new geopolitical world order. Journal of Transport Geography. Volume 105, December 2022. En:

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S096669232200206X

eMBassy of angola in Brazil

Njinga a Mbande is one of the most heroic and inspiring figures in African history, particularly in Angola. Born in 1582 in the Kingdom of Ndongo—whose territory encompassed areas that today correspond to the provinces of Malanje, Cuanza-Norte, Bengo, Luanda and adjacent regions—Njinga stood out as a symbol of resistance, political acumen and military skill. The daughter of Ngola Kiluanje Kia Samba and Guenguela Cacombe, she faced immense challenges, overcoming colonial pressures and internal conflicts to become an icon of struggle and leadership.

Njinga is remembered for her tireless defense of the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Ndongo, even in the face of brutal Portuguese colonial invasion and betrayals by local allies such as the Imbangala. Upon assuming the throne, she became a renowned military and diplomatic strategist, leading epic battles and forging key alliances to resist foreign domination. Under her leadership, the people of Ndongo resisted attempts at cultural and territorial destruction, marking one of the most important chapters in African history.

Her legacy endures. In Angola, Njinga’s name is celebrated in many ways: from monuments erected in her honor to streets, schools and institutions that bear her name. Her face appears on the 20-kwanza coin and she has become a symbol of national pride. In addition, her story has inspired films, series and books and has been highlighted in publications such as UNESCO textbooks on historic African women and in the Netflix series dedicated to African queens, narrated by U.S. singer and entrepreneur Jada Pinkett Smith. Her story has inspired books by several authors, among them Linda Heywood, José Eduardo Agualusa, Manuel Pedro Pacavira and the children’s author Otchaly, presented by the Embassy of Angola at the Federal Senate in Brasília.

Njinga a Mbande is more than a queen; she is an example of the struggle for the sovereignty, dignity and integrity of the Angolan people. Her legacy promotes commitment to the nation and the defense of freedom and cultural identity.

Despite her greatness, Njinga’s life was marked by tragedy and family conflict. After her father’s death in 1617, her brother, Ngola Mbandi, ascended the throne. Fearing Njinga’s potential, he ordered the death of her newborn son and had her sterilized.

From childhood, Njinga was prepared to face extraordinary challenges. Although she was not the direct heir to the throne, she received great attention from her father, who recognized her potential. She was trained in military and diplomatic arts and instructed in reading and writing by Portuguese missionaries. These circumstances made her a leader capable of facing both internal conflicts and external threats.

Njinga’s youth coincided with the rise of Portuguese colonial pressure, which had exploited the region since the fifteenth century. In 1571, under orders from King Sebastian of Portugal, the Portuguese intensified their campaign of conquest, resorting to an alliance with the nomadic Imbangala warriors. It was in this adverse context that Njinga forged her strength and determination.

Persecuted, she took refuge in the Kingdom of Matamba, where she found the strength to rise again. In 1621, she was called back to the kingdom to serve as ambassador in Luanda—the opportunity the queen needed to demonstrate her unrivaled diplomatic skill.

In Luanda, Njinga showed her diplomatic genius. In a historic meeting with the Portuguese governor, João Correia de Sousa, she refused to submit and sat at the same level, having one of her attendants serve as a seat—a symbolic gesture underscoring her insistence on dignity and equality. In this context, she negotiated the sovereignty of Ndongo and trade agreements that would benefit her kingdom. Converted to Christianity for strategic reasons, she adopted the name Ana de Sousa, but she never abandoned the values, culture and traditions of her people.

Njinga a Mbande, the Warrior Queen, remains a living symbol of Africa’s struggle against oppression and for freedom. Her example transcends borders, inspiring generations. More than a historic Black figure, she is a beacon of courage and resistance for all humanity.

María Del carMen fuentes Dávila fernánDez seconD secretary in tHe DiPloMatic service of Peru

"Diplomacy is the art of letting someone else have your way, while believing it is theirs"

- Dag HaMMarskjölD

On September 6, 1985, in Luanda, foreign ministers Allan Wagner and Afonso Van-Dúnem “M’Binda” signed the document that inaugurated an important diplomatic relationship between the sister republics of Peru and Angola. The Luanda Communiqué not only established formal ties between the two countries; it also marked a milestone in South–South cooperation and in the strengthening of the principles of selfdetermination and non-intervention in the postcolonial context. Forty years after its signing—and

following the first meeting of the Bilateral Political Consultations on July 9, 2025—this analysis examines the historical context, the substantive content of the agreement, and the extraordinary opportunities now opening up for bilateral cooperation which, despite its potential, currently records trade flows of barely US$ 28,000 per year.

The 1980s were pivotal in the reconfiguration of world order (Rojas Aravena, 2000). Amid the Cold War, in one of its most intense phases—countries of the Global South sought areas of autonomy and collaboration among themselves to shape their own systems of political and economic development.

On one hand, Angola was during a civil war that would last until 2002 (Hodges, 2004), having gained independence from Portugal only a decade earlier, in 1975. The African country—abundant in diamonds and oil—faced interventions by foreign powers backing different factions, even as it strove to establish national sovereignty under the leadership of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) (Malaquias, 2007).

Peru, for its part, was undergoing profound social and political transformations. After the country’s return to democracy in 1980, the administration of President Alan García Pérez (1985–1990) implemented a foreign policy of “active nonalignment,” seeking to broaden international relations and strengthen ties with Third World countries (Ferrero Costa, 2001).

Angola hosts the SADC Parliamentary Forum

Source: gga.org/angola-jose-eduardo-dos-santos/

The decision to establish diplomatic relations between Peru and Angola was not random, but rather the result of factors that converged at an opportune moment (Wheeler & Pélissier, 1971). As developing countries, the two nations shared similar experiences—economies reliant on primary-commodity exports and societies marked by cultural and ethnic diversity. In the 1980s, Peruvian foreign policy—led by Foreign Minister Allan Wagner Tizón—stood out for its openness toward the African continent and its commitment to national liberation struggles (García Montúfar, 2015). This approach coincided with Angola’s drive to secure support for national reconstruction and broader international recognition (Pinheiro, 2005).

Although brief, the Luanda Communiqué is remarkably rich in normative content. Its drafters went beyond protocol formalities to articulate principles reflecting a mature understanding of international law and the aspirations of emerging nations. The first of these is the legal equality of States, meaning that Peru and Angola—regardless

of differences in size, population or economic development—would relate on a plane of full legal equality. Respect for sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity is likewise central, reflecting both nations’ sensitivity to external interference, rooted in their own historical experiences (Ferrero Costa, 2001).

Flags of Peru and Angola

Source: A.I

One of the document’s most significant features is its explicit reference to the self-determination of peoples. Developed in the twentieth century and enshrined in the UN Charter, this principle takes on special significance in the Peruvian–Angolan setting. For Angola, self-determination validated its struggle for independence from Portuguese colonialism and, thereafter, protected its right to determine its political and economic system free from external interference (Hodges, 2004). After centuries of colonial rule, the country had long suffered from the denial of this principle (Malaquias, 2007). In Peru,

self-determination resonates with the national diplomatic tradition of defending non-intervention, a principle guiding the country’s foreign policy since the nineteenth century (Rojas Aravena, 2000). Its inclusion in the Luanda Communiqué signaled Peru’s commitment to the right of peoples to chart their own future without external pressure.

The document also clearly condemns Apartheid, colonialism, and any form of racial discrimination. This was not mere rhetoric: it reflected the political landscape of the 1980s, when South Africa’s

Apartheid regime persisted and Angola faced incursions by the South African army on its territory (Pinheiro, 2005).

According to Peru’s Central Reserve Bank (2025), Peru has consolidated its position as a regional export power. In 2024, the country set a record with US$ 75.9 billion in exports—12.4% above the previous year—producing a trade surplus of US$ 23.8 billion (PROMPERÚ, 2025). This places Peru fourth among Latin American exporters, after Mexico, Brazil and Argentina. Peru’s export basket is diversified: traditional exports (especially mining) account for 73% of the total (US$ 55.2 billion), while non-traditional exports total US$ 20.7 billion (BCRP, 2025). Agriculture, textiles, fisheries and metals processing are particularly noteworthy, where Peru has strengthened global competitive advantages (PROMPERÚ, 2025).

In 2024, Angola recorded its fastest growth since 2014, with GDP up 4.4%, driven by a rebound in the oil industry and by non-oil sectors such as fisheries, commercial services and diamond mining (World Bank Group, 2025). With 38 million inhabitants, it is the third-largest economy in Sub-Saharan Africa (International Monetary Fund, 2025). The economy remains predominantly oil-based: hydrocarbons account for 30% of GDP, 70% of government revenues, and 90% of exports (African Development Bank, 2024). Average oil output in 2024 was 1.134 million barrels per day, making Angola Africa’s second-largest producer (World Bank Group, 2025). Angola is also a major diamond producer (third in Africa), with 2024 production the highest on record up to that date (African Development Bank, 2024). Mineral reserves cover more than fifty essential minerals—gold, iron, bauxite, phosphates— offering significant collaboration opportunities for Peruvian mining companies (Hodges, 2004).

Despite both countries’ economic potential, official bilateral trade figures are surprisingly low: Peru’s exports to Angola reached only US$ 27,970 in 2023, far below Peru’s trade with other African partners such as South Africa (US$ 45 million) or Egypt (US$ 180 million) (Trading Economics, 2025). This amount—less than 0.00004% of Peru’s total

exports—reveals an almost untapped commercial potential (International Trade Centre, 2024). According to Trading Economics (2025), minor manufactures and agro-industrial items make up Peru’s exports to Angola, while imports from Angola are marginal.

Source: kokargo.com/puerto-de-luanda

The greatest opportunity for bilateral collaboration lies in the mining sector (Peru’s Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism, 2025). Peru has developed a world-class mining-services industry as the world’s second-largest copper producer and a leading producer of zinc, silver and other minerals. Companies such as Hochschild Mining, Volcan Compañía Minera, and Milpo have demonstrated the capacity to operate in complex settings similar to Angola’s (PROMPERÚ, 2025). Angola has significant deposits of manganese, copper and

gold, as well as untapped iron reserves estimated at 3 billion tons (Hodges, 2004). According to the AfDB (2024), the transfer of Peruvian mining technology—particularly in environmental management and mineral processing—could accelerate the development of these resources. While Angola’s energy sector is predominantly oil-based, it has set ambitious goals to diversify its energy matrix toward renewables (World Bank Group, 2025). Peru’s experience in solar and hydropower could help achieve these targets.

Peru has undergone an agro-export revolution. It is the world’s top exporter of quinoa and the secondlargest exporter of asparagus (PROMPERÚ, 2025), and a global leader in fresh blueberries. This experience is particularly relevant for Angola, whose government prioritizes agriculture to reduce oil dependence (World Bank Group, 2025). The AfDB (2024) estimates Angola imports around 50% of its food, representing a potential market of

US$ 2 billion per year. Peru’s best-fit products include canned fish, kiwicha (amaranth), quinoa, fine cocoa, and dehydrated fruits (Peru’s Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism, 2025). Technology transfer for pressurized irrigation and precision agriculture could transform agricultural provinces such as Malanje, Huambo and Bié (World Bank Group, 2025).

Source: kitchencommunity.wordpress.com/

Led by companies such as Graña y Montero, Cosapi and JJC Contratistas Generales, Peru’s construction sector has built experience in African markets (PROMPERÚ, 2025). Peruvian firm Graña y Montero carried out US$ 120 million in projects in Angola between 2015 and 2020, including public buildings and road infrastructure (Peru’s Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism, 2025). Angola is estimated to require US$ 100 billion to rebuild infrastructure after

the conflict (World Bank Group, 2025). Priority needs include hospitals, airports, roads (only 30% paved), ports, and social housing (African Development Bank, 2024). Peru’s capabilities in complex project management, financial engineering and anti-seismic construction translate into significant competitive advantages.

Both countries possess exceptional cultural and natural heritage. Peru received 4.4 million international tourists in 2024, generating US$ 4.8 billion (PROMPERÚ, 2025). Angola—boasting 1,650 km of Atlantic coastline, national parks and a Lusophone colonial legacy—has the capacity to build a robust tourism industry (World Bank Group, 2025). Bilateral collaboration could include community-based tourism (where Peru is a global reference), integrated tourism routes, and training in gastronomy and hospitality (Peru’s Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism, 2025). The “Andes–Angola” tourism corridor could attract travelers interested in adventure and cultural tourism.

Source: expedia.com/es/Angola.dx5

Afro-descendant communities in Peru—especially in the provinces of Lima, Ica and Piura—form a natural bridge with Angola. Afro-Peruvian rhythms such as the marinera, festejo, and landó share affinities with Angolan musical traditions like kuduro, kizomba and semba (García Montúfar, 2015). Initiatives such as a Peruvian–Angolan Afro Festival, artist exchanges and documentaries on the African diaspora in the Americas could strengthen cultural ties and help forge a shared identity.

Likewise, Agostinho Neto University and the Catholic University of Angola are among the Angolan institutions with which Peruvian universities— Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, National University of Engineering, and National University of

San Marcos—have expressed interest in creating exchange programs. The South–South Exchange Program “Caminos Africanos” – Peru, Angola and Dominican Republic 2025 is being developed in collaboration with Brazil’s Ministry of Racial Equality (MIR); the National University of San Marcos; Agostinho Neto University; and FLACSO Dominican Republic. It is a short-term exchange program for faculty and students aimed at fostering academic collaboration, research, and knowledge-sharing on combating racism and promoting racial equality.

Both countries face similar challenges in the sustainable management of natural resources. For Angola—aiming to develop its forest resources sustainably (African Development Bank, 2024)— Peru’s experience in managing vulnerable ecosystems, particularly the conservation of Amazonian biodiversity, is highly relevant. With 58 million hectares of forests (47% of national territory), Angola is a key player in global strategies to mitigate climate change (World Bank Group, 2025). Collaboration on biodiversity conservation, sustainable forest management, and reforestation techniques could yield joint projects under REDD+ mechanisms of the UNFCCC.

Peru, with 3,079 km of Pacific coastline, has accrued experience in sustainable fisheries, aquaculture, and marine conservation (PROMPERÚ, 2025). Angola, with 1,650 km of Atlantic coast, is seeking to develop its maritime potential beyond offshore oil extraction (World Bank Group, 2025). According to the AfDB (2024), bilateral cooperation could include marine aquaculture, marine protected areas, fisheriestechnology transfer, and integrated coastal-zone management.

1. The Lobito-Dar corridor: A Transcontinental Opportunity

The Lobito–Dar es Salaam Corridor—linking the port of Lobito in Angola with Dar es Salaam in Tanzania via Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—is an exceptional opportunity for Peru’s insertion into Africa (World Bank Group, 2025). Supported in part by G7 countries’ Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), the corridor is expected

to mobilize over US$ 10 billion in investment (African Development Bank, 2024). Involvement by Peruvian companies in specific areas—bridge construction, road signaling, port management— could create commercial opportunities across four African nations simultaneously (Peru’s Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism, 2025).

As the Port of Chancay becomes a regional hub and connects with Brazil across the ocean, synergies emerge with the African corridor. Angola could leverage Peru’s Pacific infrastructure to reach Asian markets, while Peru could access Africa’s Atlantic markets via Angolan facilities (Rojas Aravena,

2000). This geographic complementarity elevates the bilateral relationship beyond conventional trade, making it a strategic component of global connectivity (García Montúfar, 2015).

Source: thelogisticsworld.com/

The first meeting of Political Consultations between Peru and Angola—held as part of the celebrations of the 40th anniversary of diplomatic ties—made it possible to review achievements and set new objectives for future collaboration. In this historic encounter, the two nations agreed to cooperate in five priority areas: (1) facilitating business and exchanging goods; (2) technical cooperation in agriculture and mining; (3) infrastructure and connectivity development; (4) cultural and educational exchange; and (5) inter-institutional cooperation.

With this meeting, Peru affirmed that the Luanda Communiqué has remained relevant and valid for

four decades. The founding precepts—equality before the law, respect for sovereignty, selfdetermination, non-intervention, and rejection of all forms of discrimination—are not only still applicable; they have gained fresh relevance in today’s international context. The Angola–Peru relationship goes beyond diplomatic formalities to stand as a model of South–South cooperation based on mutual respect and complementarity (Rojas Aravena, 2000). Nonetheless, current trade figures (Trading Economics, 2025) show that the economic potential remains largely untapped.

This new phase in Peru–Angola relations brings fresh cooperation priorities to address twentyfirst-century challenges—from the climate crisis to digitalization. The goals proposed for 2030 are ambitious yet feasible: raise bilateral trade to US$ 50 million, enable US$ 200 million in investment, and consolidate Angola as a gateway for Peruvian companies into the African market (PROMPERÚ, 2025). Achieving these targets will require privatesector engagement, sustained political will, and effective institutional mechanisms.

Today’s South–South cooperation can draw valuable lessons from the Peru–Angola experience (Ferrero Costa, 2001). Principles endure when grounded in solid values, but diplomatic relations also require people-to-people exchanges, economic content, and concrete projects that benefit both sides. The brotherhood between the African savanna and the Andean cordillera, born in Luanda forty years ago, can translate its potential into tangible outcomes for both nations—within an increasingly interconnected yet also more polarized world (Rojas Aravena, 2000).

African Development Bank. (2024). Angola Economic Outlook 2024. Abidjan: AfDB. Retrieved from

https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/southern-africa/angola/angola-economic-outlook

References Banco Central de Reserva del Perú. (2025). Memoria Anual 2024. Lima: BCRP. Retrieved from

https://www.bcrp.gob.pe/publicaciones/memoria-anual/memoria-2024.html

Ferrero Costa, E. (2001). La Política Exterior del Perú: 1968–2000. Lima: Academia Diplomática del Perú. Fondo Monetario Internacional. (2025). Angola: Post-Financing Assessment. Washington, DC: IMF. Retrieved from

https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2025/09/05/pr-25288-angola-imf-executive-board-concludes2025-post-financing-assessment

García Montúfar, G. (2015). Historia de la Diplomacia Peruana. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

Hodges, T. (2004). Angola: Anatomy of an Oil State. Lysaker: Fridtjof Nansen Institute. International Trade Centre. (2024). Market Analysis: Peru–Angola Trade Statistics. Geneva: ITC. Malaquias, A. (2007). Rebels and Robbers: Violence in Post-Colonial Angola. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute.

Pinheiro, M. (2005). Angola e o Mundo: Relações Diplomáticas (1975–2002). Luanda: Texto Editores.

PROMPERÚ. (2025). Estadísticas de Exportación 2024. Lima: Comisión de Promoción del Perú. Retrieved from Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores del Perú. (1986). Memoria Institucional 1985. Lima: Torre Tagle.

https://repositorio.promperu.gob.pe/collections/4d95bee5-e1a3-40cb-88b6-61855015907e

Rojas Aravena, F. (Ed.). (2000). La Política Exterior de los Países Andinos: Entre la Tradición Autonomista y las Nuevas Interdependencias. Santiago: FLACSO-Chile.

Trading Economics. (2025). Peru Exports to Angola Database. New York: Trading Economics. Retrieved from

https://tradingeconomics.com/peru/exports/angola

Wheeler, D. L., & Pélissier, R. (1971). Angola. Londres: Pall Mall Press. World Bank Group. (2025). Angola Economic Update. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/angola/publication/angola-economic-update-boosting-growth-with-inclusive-financial-development

italo guillerMo loayza roMán tHirD secretary in tHe DiPloMatic service of Peru

Despite being separated by almost 10,000 kilometers, Peru and Angola share a defining trait: the richness of their living cultural heritage and biodiversity, which gives them tourism potential of significant strategic value. Both features represent an invaluable opportunity for the economies and societies of the two countries, making it essential to highlight their similarities as well as the development opportunities that arise in each case.

Under the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, “intangible cultural heritage,” also known as “living heritage,” is understood as the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge and skills (…) constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment (Article 2.1). It may be

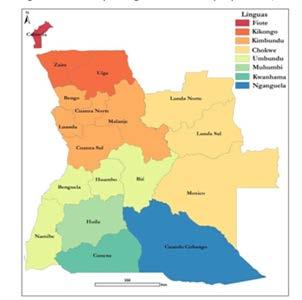

A first element to consider, in the case of intangible cultural heritage, is that of oral traditions and expressions transmitted through Indigenous languages. Both countries are home to a rich tradition of Indigenous languages and related ancestral knowledge. In Peru there are 48 recognized Indigenous languages (with Quechua and Aymara the most widely spoken, according to the XII National Population Census, VII Housing Census and III Census of Indigenous Communities, 2017). In Angola there are more than 40 Indigenous languages, among which Umbundu, Kikongo and Kimbundu stand out, according to the 2014 General Census of Population and Housing.

manifested, in particular, in the following domains: (i) oral traditions and expressions; (ii) performing arts; (iii) social practices, rituals and festive events; (iv) knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; and (v) traditional craftsmanship (Article 2.2).

Linguistic diversity in both nations represents not only a source of identity and cohesion for communities, but also an attraction for those seeking authentic experiences and direct contact with knowledge passed down from generation to generation. Cultural tourism finds in these Indigenous languages a gateway to stories, myths, songs and poems that have withstood the test of time and keep the essence of their peoples alive.

The wealth of oral expression in Peru’s high Andean and Amazonian regions, as well as across Angola’s provinces, facilitates the creation of tourism routes focused on interaction with local communities, participation in ritual festivities, and learning ancestral artisanal techniques. In Angola, for example, initiatives such as the Luanda Carnival or the National Festival of Culture (FENACULT) stand out, as does the recently approved Plano de Apoio e Promoção da Cultura (PLANACULT), under Presidential Decree No. 82/25, to develop the creative industries—following foreign experiences such as those of Nigeria, Brazil and Portugal, among others.

Opportunities are not limited to Angola’s linguistic diversity or to the ceremonies of ethnic groups such as the Ovimbundu, Bakongo and Chokwe. A second area to highlight is music. Traditional rhythms such as semba, together with kizomba, kuduro, and the tufo dance, offer multiple avenues for promotion that reflect deep cultural traditions—facing significant challenges of preservation and dissemination after decades of internal conflict. These elements of connection and cohesion enable communities to reinforce their unity, with positive impacts on local economies.

As Baratti (2022) notes, while certainty is not possible, it is interesting to observe the influence that semba may have had on other well-known rhythms in the Americas, such as Brazilian samba. According to the author, a common explanation for the term “samba” is its Bantu etymology, derived from the Kimbundu word semba, meaning umbigada (belly-bump movement). Thus:

The etymological derivation of ‘samba’ from the Kimbundu term ‘semba’ seems to have generally prevailed over the years in the academic literature on samba (Sandroni 2001). The preference for an etymology of ‘samba’ that privileges a movement, the umbigada might have implicitly reproduced a colonial attitude that was more generally at work in the examination and classification of the cultural expressions of the African colony. This could have implied a process according to which the umbigada would have received much more attention than other elements in the description of the African dances (on the topic, cf. Lima Silva 2010) (pp. 6-7)

In Peru, folk music such as the huayno, the marinera, the festejo and the vals criollo, along with traditional instruments such as the charango, the quena and the cajón, are living manifestations that have transcended borders and generations. These melodies not only accompany the festivities, but also express collective stories, values and the resilience of their native peoples. Music festivals, patron saint celebrations and community gatherings in different Peruvian regions have become spaces for preservation and intercultural dialogue, where tourism plays a fundamental role in the revaluation of these artistic expressions.

These manifestations deserve and require a reinforced level of protection, in order to guarantee their integrity and knowledge over time. An example of this is what happened with Creole music and song. With Vice-Ministerial Resolution No. 225-2022-VMPCIC/MC of October 17, 2022, it was declared Cultural Heritage of the Nation, for:

The resolution also provides that every five years a report be prepared on the state of the expression “so that the institutional register can be updated regarding changes in the manifestation, risks that may arise for its continuity, and other relevant aspects.” Examples such as the foregoing offer experiences that other countries—Angola, for instance—could take as a starting point to create a detailed registry for protecting their cultural expressions, such as music.

As can be seen, music—as a cultural manifestation of the people—demonstrates its importance not only within but also beyond national borders. Both Angola and Peru, in their many musical expressions, face the twin challenge of promoting and developing them, while also protecting their historical records, enabling both countries to preserve the Indigenous knowledge and wisdom that gave rise to such important cultural manifestations—so as to guarantee their protection across space and time.

The cultural heritages mentioned above are deeply interrelated with the natural heritage of both countries. The former draw nourishment from the latter, which inspire and sustain them, as can be seen in dances that keep knowledge of plants, animals and nature-derived traditions alive. In this sense,

(…) to constitute a musical culture built by popular sectors of the mestizo, Afrodescendant and migrant population in the indicated initial nuclei of practice, through a historical process that extends from the end of the nineteenth century and the entire twentieth century; enveloping within itself the practice of various musical genres associated both geographically and symbolically with the coast of the country, in whose nucleus are located the Creole waltz, the polka and the marinera limeña; having an extended community of bearers whose ability to adapt and incorporate new elements to their techniques and repertoires, in line with but not subject to the transformations in the music industry, have allowed the generation of spaces for practice and transmission that have ensured the safeguarding and validity of Creole music and song; all of which has made it one of the main elements of Peruvian musical identity.

cultural heritage is nourished by natural heritage, forming an inseparable bond whose integration offers significant potential for the development of sustainable tourism. What follows refers to natural heritage, where national parks and waterfalls stand out.

Source: ich.unesco.org

As in Peru’s case, Angola’s wealth lies not only in culture but also in nature. Located in a remarkable position on the African continent—with a tropical climate along the western coast and, inland, diverse geography spanning from the Namib Desert to Huíla Province (home to Bicuar National Park)—Angola has multiple opportunities to leverage in promoting its tourism industry.

One example is Quiçama National Park, in Luanda Province, covering approximately 9,600 km²—one of the country’s greatest natural jewels. The park offers a variety of ecosystems, including wooded savannas, grasslands, riparian forests, coastal mangroves and floodplains, enabling observation of wildlife such as elephants, giraffes, zebras, antelopes, manatees, migratory birds, sea turtles, among other species. Given its recovery since the end of the internal conflict in 2002, it is an excellent destination for safaris as well as birdwatching.

Another example is the Kalandula Falls, in Malanje Province. At 105 meters high and 400 meters wide, they are among Africa’s largest waterfalls by volume of water. Their flow reaches its peak during the rainy season (February–April), making them an attractive site for tourism development given the vast national

and local opportunities. Ecotourism and adventure tourism are complemented by hiking, cycling routes, and expeditions to discover the region’s unique biodiversity, where contemplation of unexplored landscapes invites reflection and wonder.

In Peru’s case, Manu National Park—created by Supreme Decree No. 0644-73-AG of May 29, 1973— covers 1,716,295.22 ha and protects one of the most biodiverse areas on the planet, with ecological wealth that includes high-Andean forests, cloud forest, rivers, valleys and gorges, more than 1,000

Such designations give internationally protected sites greater visibility, facilitating cooperation mechanisms for their protection and sound development. While Angola currently has the city of M’banza Kongo inscribed as a World Heritage Site, this protection could be extended to sites such as those mentioned above. This would ensure not only protection by the country itself (through pertinent regulations, funding and monitoring of security and access, among other aspects), but also the participation of other States or international organizations to provide tools for care and preservation.

bird species and over 200 mammal species, notably jaguars, tapirs, peccaries, deer, and spider monkeys, among others. It was declared a Biosphere Reserve in 1977 and a UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site in 1987.

As the foregoing examples show, Angola is home to important places that display rich biodiversity which—drawing not only on nearby experiences but also on those of Peru—could be the basis of a robust tourism strategy to enhance their value and foster domestic and international tourism. Thus, with due regard for environmental stewardship and ecologically responsible, sustainable tourism, Angola has the tools to strengthen this sector by exploring the many opportunities afforded by its rich geography.

As seen above, Angola has enormous tourism potential rooted in its living heritage and natural diversity, alongside challenges in infrastructure, sustainable management and promotion that must be addressed to unlock that potential. In this regard, Peru’s experience offers multiple lessons: how to make cultural and natural heritage a driver of sustainable tourism; how to integrate local communities; how to manage eco-tourism and heritage destinations; and how to leverage gastronomy and festivals as key cultural attractions.

Peru and Angola alike show that living heritage and biodiversity are not only cultural legacies, but also engines of sustainable tourism. In this sense, Angola can draw on Peru’s experience in heritage and tourism

management, while Peru finds in Angola a partner with different yet equally valuable realities for cultural exchange and the strengthening of international ties.

In conclusion, the articulation between cultural and natural heritage allows us to think not only in terms of tourism appeal, but also national identity, sustainability in the tourism industry, and projection not only at the regional but even the global level. In this way, both countries—safeguarding ancestral knowledge and biodiversity—can promote a development model that balances economic growth with the conservation of their heritage for generations to come.

References

Angolan dances (2022). Meet SEMBA - Angolan Dances: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s-MdrLd4oeI https://atem-journal.com/ATeM/article/view/4065/3291

Baratti, Nina (2022). ““Semba Dilema”: On transatlantic Musical Flows between Angola and Brazil”. Archiv fur Textmusikforschung. Atem. Nr. 7,2,2022.

CNN Travel (2024). Angola's incredible "sacred" waterfall that you've probably never heard of

https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2024/04/04/increible-cascada-sagrada-angola-kalandula-trax/

Diário Expansão (2025). After Planagrão, Planagás, Planapescas and Planapecuária, now comes Planacult.

https://expansao.co.ao/angola/detalhe/depois-do-planagrao-planagas-planapescas-e-planapecuaria-agora-vem-ai-o-planacult-65099.html

Government of Angola (2016). Final results of the general census of the population and housing of Angola 2014.

https://www.ine.gov.ao/Arquivos/arquivosCarregados//Carregados/Publicacao_637981512172633350.pdf

Ministry of Culture of Peru. Database of Indigenous or Native Peoples.

https://bdpi.cultura.gob.pe/lenguasf

National Service of Natural Areas Protected by the State (2025). Manu National Park

https://www.gob.pe/institucion/sernanp/informes-publicaciones/1948163-parque-nacional-del-manu?utm_source=chatgpt.com

UNESCO (2003). Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.

https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/es/text/594743

Vice-Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Cultural Industries (2022). Vice-Ministerial Resolution No. 25-2022-VMPCIC/MC.

https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/dispositivo/NL/2116192-1

aMBassaDor jorge raffo carBajal Director general of Peru for africa, tHe MiDDle east anD tHe gulf countries

The start of operations at the Port of Chancay on Peru’s north coast opens up possibilities for South–South trade and suggests that, via a Latin American multimodal corridor, it would be possible to reach the Indian Ocean by using Angola’s Lobito rail corridor.

Since the early twentieth century, the Lobito railway corridor and the Port of Lobito in Angola have played a fundamental role as an outlet for minerals from the African interior to international markets. Minerals such as copper and zinc were transported from the resource-rich areas of what is now southern the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and northern Zambia to the Atlantic coast, consolidating Lobito as a key logistics hub in Southern Africa. However, after decolonization and armed conflicts

in the region, this infrastructure lost relevance and remained underutilized for several decades.

In today’s global context—marked by intense competition for strategic minerals—the Lobito rail corridor has regained prominence. It is one of the continent’s most important infrastructure initiatives, as the first open-access transcontinental railway route. Its design directly links the mining areas of the DRC and Zambia (both landlocked) with this Angolan port, thereby facilitating the export of critical mineral resources such as copper, cobalt and coltan. The latter is especially relevant, as the DRC accounts for around 80% of world production, making this project a nerve center for global technology industries.

At present, transporting mining products from Zambia (which borders Angola) to the Atlantic can take up to 45 days, due to the fragmentation of the rail network and congestion along the routes. With the modernization of Angola’s rail corridor and its efficient integration with the Port of Lobito, this time is expected to fall to less than a week. This improvement will significantly enhance regional competitiveness by reducing logistics costs, attracting foreign direct investment and positioning Lobito as a new commercial “hub” for Southern Africa.

The strategic importance of the Lobito corridor has drawn the attention of Peru and other major international players. Peru’s proposal is to connect this corridor with the Zambian network that reaches the Indian Ocean (the TAZARA line, for Tanzania–Zambia Railway Authority) so that goods would exit—or enter—through the Port of Dar es Salaam. In 2023, the European Union, the United States, the African Development Bank, Angola, the DRC and Zambia signed a Memorandum of Understanding to revitalize the corridor’s rail infrastructure, which had been severely affected by a decade of civil war (now happily concluded). A central objective of this

partnership, for the United States and Europe, is to secure—via Lobito—alternative supply routes for critical minerals needed for the energy transition and technology production. For Peru, it is an opportunity to expand fruit exports, which over the last fifteen years have grown by 122%.

The geopolitical spotlight on the rail corridor was underscored by President Joe Biden’s visit to Angola from December 2–4, 2024. It was the first state visit by a U.S. president to Angola and the only one to the African continent during his term. Although bilateral issues were discussed, the main focus was support for the Lobito corridor as a strategic component of U.S. foreign policy toward Africa. Despite initial skepticism about the U.S. financial commitment, the Trump administration has recently reaffirmed its willingness to invest through its diplomatic mission in Luanda.

On July 8–9, 2025, Peru and Angola held the first meeting of the Political Consultation Mechanism, where multimodal port interconnection as a means to expand exports was a central item for both delegations. In 2024, Peru posted solid economic results: GDP grew 3.3%, inflation was contained at 1.97%, and exports reached a historic record of US$ 74.664 billion.

The Lobito corridor thus emerges as a cornerstone of Southern Africa’s logistics architecture and a first-order geopolitical instrument. Its consolidation

could accelerate mineral exports, spur development in marginalized regional economies, and generate new synergies between Africa and international South–South partners such as Peru and South America. Nevertheless, the corridor’s success will depend on inclusive, sustainable and coordinated implementation—capable of aligning Angolan interests with a shared vision of integration with Peru (based on the notion of expanded Africanness) and of regional development with its African partners.

antonio josé cHang Huayanca seconD secretary in tHe DiPloMatic service of Peru

In the Historical Dictionary of the Spanish Language (1960–1996) the word angola appears in its first sense as “(…) a native or someone coming from the region of Angola” (Real Academia Española, 1996), together with several examples of its use in early Spanish texts, two of which I wish to highlight. The first, drawn from a compilation by Boyd-Bowman and ultimately linked to a Mexican text from 1562, associates the term with a proper name: “Pedro Angola, de la tierra de Angola” (Boyd-Bowman, 1971). The second comes from this passage in Ricardo Palma’s Tradiciones peruanas: “many of the associations (…) managed to place their treasuries in a comfortable position. The angolas, caravelís, mozambiques, congos, chalas and terranovas purchased lots on the far-flung streets of the city” (Palma, 1893/2005). Both examples show that in Spanish the word angola has not only been used as the proper name of a country; it has also historically described a person’s proper name or an ethnic group linked to that African region. In what follows I will refer to the case of María Angola, the name borne by several bells located throughout Peru, as well as by an irrigation canal in the province of Cañete, department of Lima.

Perhaps the most famous bell in all Peru is the María Angola of Cusco Cathedral. Countless legends surround its origin; many share the idea that there was a lady of the same name who donated her jewels to pay for its casting and subsequent donation to the Cusco church. The bell was also mentioned by Peruvian indigenist writer José María Arguedas in his novel Los ríos profundos. It is likely the oldest and largest of all the homonymous María Angola bells in Peru—and the only one located at a site inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage property, the Historic Centre of Cusco (1983). It is worth noting that this celebrated Cusco bell was used during the proclamation of U.S.-born Peruvian Robert Francis Prevost as the new Supreme Pontiff of the Catholic Church. In May of this year the Archdiocese of Cusco announced on its Facebook page that “with the imposing peal of the María Angola bell, from the heights of our venerated Basilica Cathedral, the Archdiocese of Cusco proclaimed the new Pope Leo XIV as Peter’s Successor” (Arzobispado del Cusco, 2023).

Another representative María Angola bell is located in the district of Zaña, on Peru’s northern coast—a locality which, as in the previous case, is associated with a UNESCO recognition, specifically as a “Site of Memory of Slavery and African Cultural Heritage,” the first recognition of its kind granted to an Afrodescendant community in Peru and in all the countries of the Pacific coast, according to the Ministry of Culture. In July 2021 the Afro-Peruvian Museum of Zaña posted on Facebook about the “mystery of the María Angola bell” at the local parish. The post notes that the meaning of the name is enigmatic, concluding that “what is certain is that Angola refers to an African people or nation,” and

adding that, according to researcher Manuel Álvarez Nazario, mariangola was “a dance of African roots.” According to the museum, only two terms of African origin remain in Zaña: the street name malambo, and María Angola (Museo Afroperuano de Zaña, 2021). Local tradition recalls the use of the bell to announce Masses and funerals and to sound alerts in the event of river flooding or other calamities. The post even mentions local songs dedicated to the María Angola bell and a tradition claiming that the bell “flew and moved from one place to another.” The article rightly notes that there are several bells bearing that name throughout Peru, citing the cases of Cusco, Huarochirí and Aymaraes.

It is worth adding that while writing this piece I identified yet another María Angola bell, different from those mentioned above, this time in the district of Mangas, Bolognesi province, department of Áncash. According to a 2023 post by the district municipality, the San Francisco de Mangas church was built in the mid-seventeenth century and was declared Cultural Heritage of the Nation in 2008; its bell tower, built in 1737, is where the local María Angola bell is found. Why are there so many María Angola bells in Peru? How many are there in total? Was María Angola a real person? None of these questions has certain answers.

María Angola refers not only to the name of several Peruvian bells, but also to an irrigation canal in the province of Cañete, department of Lima. According to the thesis of engineer Richard Huatuco at the

National University of Engineering, the María Angola Canal begins at the Fortaleza intake on the Cañete River and forms the boundary between the districts of Imperial and San Vicente (2020). The canal is also linked to the district of San Luis, which—through Ministerial Resolution No. 511-2018-MC of Peru’s Ministry of Culture—was recognized as a “Living Repository of Collective Memory, as it constitutes one of the nuclei of the historical and artistic memory of the Afro-Peruvian presence in Peru, whose legacy has transcended both its time and its region of origin” (Ministerio de Cultura del Perú, 2018).

The María Angola Canal is intimately tied to the memories of Cañete’s eldest inhabitants. On March 9 of this year, the online outlet Al Día con Matices (Diario Oficial Judicial de la Corte Superior de Justicia de Cañete–Yauyos) published a short article titled “The Laundresses and the María Angola Canal…,” recalling how, many decades ago, the canal was a Saturday social space for the women and children of Cañete. According to the article, rural women set out early in groups for the canal, carrying large bundles of dirty laundry on their backs. They set up along its banks with basins and tubs and began scrubbing clothes on the stones. Once clean, the garments were spread over cane and local shrubs to dry in the sun. Meanwhile, the children who accompanied the women played in one of the natural pools formed by the canal’s waters.

The canal remains important for the people of Cañete to this day, and recent years have seen announcements of improvements to its hydraulic infrastructure. In March 2022 the Lima Regional Directorate of Agriculture laid the cornerstone for

a project to improve water service for the María Angola Canal irrigation system in the districts of San Luis and Imperial, valued at more than three million soles. The project included roughly six kilometers of concrete-lined canal, thirteen reinforced-concrete lateral intakes, and a vehicular bridge to strengthen crossings with urban-valley areas, benefiting 2,700 farmers in Cañete. Later, in October 2023, the District Municipality of San Luis announced, together with the Irrigators’ Board, works to restore a section of the María Angola Canal that had been closed off by local farmers, causing flooding of homes in the urban area.

In this sense, it can be concluded that the María Angola bells and canal are a concrete illustration of how, over the centuries, this link—recalling the arrival and settlement of people of Angolan origin during the Viceroyalty of Peru between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries—has endured in Peruvians’ collective memory.

Arguedas, J. M. (2011). The deep rivers. Fondo de Cultura Económica. (Original work published in 1958).

Archbishopric of Cusco. (2023, May). Facebook post about the María Angola bell.

Boyd-Bowman, P. (1971). Geographical index of more than 56,000 inhabitants of Hispanic America (1493–1600). Caro y Cuervo Institute.

Huatuco, R. (2020). Hydraulic study of the María Angola canal in Cañete. National University of Engineering. Ministry of Culture of Peru. (2018). Ministerial Resolution No. 511-2018-MC.

District Municipality of Mangas. (2023). Informative note on the San Francisco church and its María Angola bell.

Afro-Peruvian Museum of Zaña. (2021, July). Facebook post about the María Angola bell.

Palma, R. (2005). Complete Peruvian traditions. Ayacucho Library. (Original work published in 1893).

Royal Spanish Academy. (1996). Historical Dictionary of the Spanish Language (1960–1996). RAE. UNESCO. (1983). Historic Center of Cusco. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Regional Directorate of Agriculture of Lima. (2022). Press release on the María Angola canal improvement project.

District Municipality of San Luis. (2023). Statement on recovery work on the María Angola canal. References

josé yéPez castro counselor of tHe DiPloMatic service of Peru

On July 18, 1918, Nelson Mandela was born in a Xhosa village in South Africa, as a member of the Thembu royal house. He was given the name Rolihlahla, which in Xhosa means “troublemaker” or “mischief-maker.” At school, following local practice, his teacher Miss Mdingane changed his name to Nelson [1] to make it easier for Britons to pronounce.

He studied law at the University of Fort Hare but did not complete the degree there. Mandela became involved in a protest over poor food quality and was expelled from the institution. He later qualified as a lawyer. Few know that his pastimes included dancing, long-distance running, and boxing.

As is well known, Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment during the Rivonia Trial in 1964, essentially for his struggle against apartheid. During his twenty-seven years in prison, he bore the prison number 46664, which later became a symbol of nonviolent liberation.

From behind bars, Mandela led a peaceful resistance, becoming a global emblem of the fight for freedom. One of the most significant milestones of those twenty-seven years was his rejection of an offer of conditional release, as it required him to renounce the ideals and principles for which he had fought. Finally, on February 11, 1990, Mandela was released.

" No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin, or his background, or his religion." Nelson Mandela

Upon his release, Mandela launched international efforts to dismantle apartheid. In his liberation speech he stated that the system had no future and that only a united, democratic, non-racial South Africa was the path to peace and racial harmony [2]. Mandela and then–President Frederik de Klerk maintained a tense but respectful relationship. They came from opposite worlds—Mandela, a Black leader; de Klerk, leader of the regime that had imprisoned him. Yet both assumed the role of statesmen and shared a common objective: to end apartheid.

In this regard, the former Secretary General of the United Nations, Ambassador Javier Pérez de Cuellar declared that one of his "most satisfactory experiences as Secretary General was to be talking with Nelson Mandela and Frederik de Klerk and to feel the mutual respect that had united these two South Africans, one black and the other white"[3]

In 1993, the Norwegian Nobel Committee decided to jointly award the Nobel Peace Prize to both Nelson Mandela and Frederik Klerk "for their work for the peaceful end of the apartheid regime and for laying the foundations for a new democratic South Africa"[4].

In his address, Francis Sejersted, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, highlighted the lack of bitterness that characterized Mandela since his release, noting Mandela’s own words that “he would have harbored bitter thoughts if he had had no work (…) that if all those who have made so many sacrifices for justice could see that they had not been in vain, that would help to dispel the bitterness in their hearts."[5]

" Do not judge me by my successes, judge me by how many times I fell down and got back up again." Nelson Mandela a

Source: yourclassical.org

In the April 1994 elections, Nelson Mandela was elected President with 63% of the vote, becoming the first Black president of the Republic of South Africa at the age of 75. Beyond any prior institutional change, the election of a Black man to the presidency marked the definitive end of apartheid and the beginning of a new democratic era in the country.

For Mandela, national reconciliation was a priority of his administration so that the nation could heal the wounds of decades of hatred and internal conflict. Perhaps one of the most renowned institutions created during his term was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, where both victims and perpetrators could testify to the events that had occurred to prevent their repetition in the future. Finally, in 1999, Nelson Mandela left the presidency without seeking re-election or clinging to power.

Nelson Mandela will be remembered as the symbol of the struggle against apartheid and of the subsequent reconciliation under way in South Africa. In a world plagued by conflict, inequality, and undeniable climate change, his words invite reflection: “When the history of our time is written, will we be remembered for having done the right thing, or for having turned our backs on a global crisis?” [6] The answer lies in our hands.

References

Norwegian Nobel Committee. (1993). The Nobel Peace Prize 1993 – Press Release. The Norwegian Nobel Committee. Retrieved from

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1993/press-release

Pérez de Cuéllar, J. (1997). Memoirs: Messages from a Secretary-General, 1982-1991. Madrid: Editorial Plaza & Janés.

Sejersted, F. (1993, December 10). Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony Speech. The Norwegian Nobel Committee. Recuperado de

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1993/ceremony-speech

Mandela, N. (1994). Long Walk to Freedom. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Mandela, N. (1990, February 11). Nelson Mandela’s Address on the Day of His Release from Prison. Cape Town: African National Congress.

Mandela, N. (2005, February 3). Speech at the Launch of the Global Campaign to Make Poverty History. London.

Notes

[1] Mandela's phrase corresponds to his Liberation Speech (February 11, 1990). Retrieved from:

https://www.nelsonmandela.org/biography

[2] Mandela's phrase is from a lecture Make Poverty History), Retrieved from:

http://www.mandela.gov.za/mandela_speeches/1990/900211_release.htm

[3] Pérez de Cuéllar Book. Pilgrimage. P. 417

[4] MLA: Nobel Peace Prize 1993. NobelPrize.org. Dissemination of the 2025 Nobel Prize. Tuesday, August 19, 2025

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1993/summary/

[5] Award ceremony speech. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach 2025. Tue. 19 Aug 2025.

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1993/ceremony-speech/

[6]

https://historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/a/10-frases-nelson-mandela-que-resaltan-su-lucha-porderechos-humanos_21576

Chicken Muamba is a flavorful chicken stew considered Angola’s national dish. Red palm oil (dendê oil) is one of its signature ingredients, giving it a unique aroma and taste. This oil can be hard to find in modern supermarkets, but you can substitute peanut oil plus paprika.

Chicken Muamba holds a special place in Angolan culture. It is often prepared for family gatherings, parties, and cultural celebrations. More than just food, it is a symbol of community, heritage, and Angolan life. The ingredients themselves tell a

- Chicken pieces

- Red palm oil

- Lemon juice

- Garlic cloves

- Onion

story: okra (quiabos) and pumpkin reflect African agriculture, while red palm oil, derived from the palm, signifies the country’s natural resources.

Marinating the meat, the right balance of spices, and the accompanying sauce give this stew a flavor deeply cherished by Angolans. It is traditionally served with funge (funje)—a staple in Angola—made by cooking cornmeal with water until smooth and elastic. It is similar to polenta, but a bit firmer, and is the classic accompaniment to the stew.

- Okra (quiabos)

- Pumpkin

- Chicken broth

- Spices: paprika, chilli (gindungo)

- Optional: tomatoes

1. Cut the chicken into pieces and marinate with lemon juice, 4–5 garlic cloves, and a little salt. Let rest for at least 30 minutes.

2. In a Dutch oven or heavy pot, heat red palm oil (or palm butter). Add the onions and sauté until soft.

3. Add the marinated chicken pieces to the pot and cook until brown

4. Stir in the spices (paprika and gindungo/chili). Add the pumpkin and okra.

5. Pour in the chicken stock (or water, if stock is unavailable).

6. Cover and simmer gently for about 40 minutes, until the chicken is tender and the flavors meld.

7. Serve hot with funge.

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR AFRICA, THE MIDDLE EAST AND GULF COUNTRIES

CUMANANA XLIX – SEPTEMBER – 2025

Editorial Board

Amb. Jorge A. Raffo Carbajal

Min. Marco Antonio Santiváñez Pimentel

M.C. Eduardo F. Castañeda Garaycochea

Editorial Team

Amb. Jorge A. Raffo Carbajal, Director General and Managing Editor

Third Secretary Berchman A. Ponce Vargas, Content Director

Third Secretary Giancarlo Martínez Bravo, Editor for the English Edition

Third Secretary Berchman A. Ponce Vargas, Editor for the French and Portuguese Editions

Gerardo Ponce Del Mar, Layout Designer

Jr. Lampa 545, Lima, Peru

Phone: +51 1 204 2400

Email: peruenafrica@rree.gob.pe

Legal Deposit No. 2025-03899

ISSN: 3084-7583 (online)