ALGERIA

Second Secretary MatíaS Zanella Giurfa

Since I started working at the Embassy of Peru in Algeria in April 2021, I have had the opportunity to attend numerous local music performances, where I could not help but notice the presence of a musical instrument that stood out on stage much like a wild card in a deck – different from the rest, yet essential to the harmony of the (musical) game.

I am referring to our Peruvian cajón: an instrument that originated in the 16th century among enslaved African communities in southern Peru, who were forbidden from using drums or expressing any cultural manifestations from their homelands. Yet, their ingenuity led them to use any object capable of producing sound when struck to make music – from hollowed-out gourds to wooden boxes.

The Peruvian cajón as we know it today took on its current shape and dimensions in the 19th century, thanks to the Afro-Peruvian musician Porfirio Vásquez: 47 cm in height, 32 cm in width, with a round hole in the centre of one side. The addition of strings inside the box would come much later, during the 1950s in Trujillo and Chiclayo [cities on Peru’s northern coast].

Today, the Peruvian cajón is present in Algeria –it is back in Africa – where it is used by numerous local musical groups and genres. With the intention of learning about the history of its presence in this country, I decided to interview the Algerian musician and composer Mohamed Rouane – born in 1968 in the district of Belouizdad, Algiers – who incorporates the cajón into his musical performances. I had the opportunity to meet Mr. Rouane thanks to his participation in the celebration of Peru’s National Day in Algeria on two occasions, during which he performed both Peruvian and Algerian music –accompanied by the cajón, of course.

Source: cultura.cervantes.es

Mr. Rouane told me that he began his professional musical career in 1995, taking an interest in Algerian popular music and founding, in that same year, together with two friends – Salma Kouirete and Farouk Azibi – a musical trio named Méditerranéo. The group blended Flamenco and Gypsy Rumba with Algerian songs performed in a flamenco style. After leaving Méditerranéo in 2002, he pursued a solo career from 2004 onwards, favouring the mandole algérien (similar to a mandolin) – a traditional instrument of the Algerian Chaabi genre. Since then, Mr. Rouane has sought to “adapt world music [to the mandole]” and “blend all musical expressions” through an Algerian lens, in order to develop a musical genre he himself calls Casbah-jazz .

In Casbah-jazz, Algerian instruments such as the mandole and the "derbake" (a conical-shaped drum) converge with international instruments such as the viola, the electric guitar, and the cajón. He suggests that I listen to his music album Rêve.

- Do you know the history of the cajón? I ask.

- Partly. I discovered it through the music

of Paco de Lucía, who is a fantastic performer, and the flamenco singer Lola Flores, both of whom incorporated it into their performances, he replies.

I tell him that, in 1977, Paco de Lucía was touring South America and, while in Lima, had the chance to hear the Peruvian cajón master Pedro Carlos Soto de la Colina — known as "Caitro Soto" — at a party at the Spanish Embassy in Peru. From that moment, the Andalusian musician incorporated the cajón into his performances.

-When did the Peruvian cajón

arrive in Algeria?" I ask him.

- I was one of the first Algerian artists to incorp-

orate the use of the Peruvian cajón in the mid-1990s, when I began my career as a professional musician. Another group

The Bey’s Palace is located in the city of Constantine, Algeria’s historical jewel, where history and architecture intertwine through centuries of civilisation, with Roman, Ottoman, and Arab legacies.

Known in antiquity as Cirta, Constantine was the capital of the Kingdom of Numidia and an important administrative centre of the Roman Empire. Due to its position along trade routes, it was a strategic economic and cultural hub in that era—and remains so today.

Constantine’s unique landscape, set atop a rocky massif overlooking the deep Rhumel River gorge, has given rise to the construction of extraordinary bridges. Among them is the Sidi M’Cid Bridge, a masterpiece of engineering suspended over the void, a symbol of the creativity of the city’s inhabitants.

Today, the city shines through its modernity, its culinary traditions, its bridges, and its historical monuments.

Within this context, the Bey’s Palace, built during the Ottoman Empire, stands out. In fact, during the 16th century, Constantine was the seat of the Beylik of Eastern Algeria. During this period, the city flourished under the leadership of Bey Ahmed.

Ahmed Bey Ben Mohamed Chérif (1806–1850) was the last Bey of Constantine under Ottoman rule in Algeria, governing from 1826 until the French occupation in 1837. He was a prominent leader who resisted the French invasion of the region. Renowned for his administrative and military abilities, he modernised his territory and preserved Ottoman and Islamic culture in the face of European influence. After the fall of Constantine in 1837, he continued to resist French colonisation until his eventual surrender in 1848.

The Ahmed Bey Palace, locally known as Dar El Bey, was built between 1826 and 1835 during his reign. This building is a masterpiece of Ottoman architecture in Algeria, combining Islamic, Eastern, and Mediterranean elements.

The Bey’s Palace is an emblematic example of Arab-Islamic architecture. Designed around interior courtyards and adorned with mosaics, fountains, and gardens, it reflects the cultural refinement and spirituality inherent to Islamic tradition. In addition to serving as Bey’s residence, the palace also fulfilled an administrative function, symbolising the authority’s power and prestige. The palace is not

only a representation of Ottoman cultural richness in Algeria—it also stands as a symbol of resistance and a testament to the pre-colonial era.

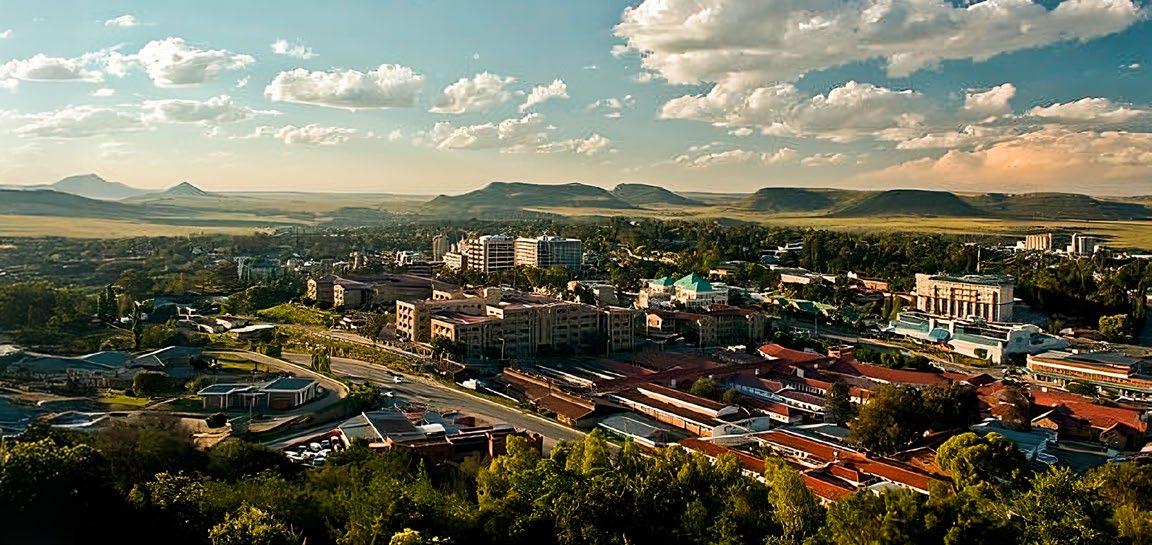

LESOTHO, THE “KINGDOM IN THE MOUNTAINS”, AND ITS SIMILARITIES WITH THE PERUVIAN ANDES

M.C. Eduardo CastañEda GarayCoChEa

The Kingdom of Lesotho (formerly known as Basutoland before gaining independence from the United Kingdom in 1966), located in the southern part of the African continent, is one of the smallest landlocked countries in Africa. However, it boasts a unique geography and a rich variety of flora and fauna which, among other attractions, give it strong tourism potential.

Surrounded by South Africa, Lesotho has a population of around 2.3 million people, an estimated 15% of whom live in South Africa due to close economic ties with the “Rainbow Nation”.

English is the official language of Lesotho (a legacy of its colonial past), alongside Sesotho (an African language spoken in the southern part of the continent)—similar to how Spanish is the official language in Peru, along with Quechua, Aymara, and other indigenous languages in the regions where they are predominant.

Lesotho is also known as the “Kingdom in the Mountains” due to its mountainous terrain, with a minimum altitude of 1,000 metres above sea level, and 80% of its territory lying above 1,800 metres.

This feature causes significant temperature variations between day and night, making it necessary for Basotho people to wear warm clothing at night—just as in the Peruvian Andes. Snowfall is also common during the winter months, given that elevations reach up to 3,500 metres above sea level (Mount Ntlenyana).

Due to these drastic temperature changes, Basotho people traditionally wear blankets for warmth and use woollen hats or hoods to shield themselves from the strong winds and cold—much like the poncho and chullo are common garments in the Peruvian Andes. Likewise, due to the rugged terrain, Basotho horses (small in size) and mules remain widely used means of transport, just as llamas and mules are still used in Peru’s steep mountain regions.

Source:

Source:

Source:

Lesotho’s main economic sector is agriculture, with crops such as wheat, maize, fruits, and vegetables. This is followed by mining— primarily diamond extraction—as well as textile production for export. These sectors closely mirror the prominence of agriculture and mining in Peru’s Andean regions. Additionally, Lesotho earns significant revenue from selling drinking water and energy to South Africa, helping to meet demand during times of water scarcity.

Regarding religion, the Lesotho population is predominantly Christian (90%), with Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, and indigenous traditional religions comprising the remaining 10%, further resembling the predominantly Christian Andean region of Peru.

Among Lesotho’s traditional musical instruments are wind instruments such as the lekolulo (a type of flute) played by farmers and shepherds—much like the quena is used in the Peruvian Andes.

Lesotho's cuisine is characterized by simple, spice-free cooking methods and a few ingredients. The consumption of corn, a typical Andean staple, is particularly notable..

As for sport, football is the most popular activity in Lesotho, despite the country’s high altitude, which, as in Peru’s highland communities, does not pose an obstacle to playing the game.

In terms of flora, despite its small territorial size, this African country is home to a significant number of native species. Its mountains harbour a wide variety of high-altitude plant life (approximately 3,094 species). One notable example is the aquatic plant known as the Cape blue water lily (Nymphaea capensis), which may be seen as comparable to Peru’s totora.

Lesotho's fauna includes endemic species not found elsewhere, such as the Maloti Lancen Craig lizard and the ice rat, whose Andean equivalents would be our Proctoporus titans and the Andean mouse, respectively.

Due to its altitude, the imposing ravines of Lesotho are reminiscent of the deep Andean gorges, with their flowing rivers and cascading waterfalls offering breathtaking panoramic views.

This African country boasts high-altitude wetlands that ensure water stability and are protected similarly to Peru’s wetlands, such as those found over 3,500 meters above sea level in the Titicaca National Reserve and the Salinas and Aguada Blanca National Reserve.

The reflection of this natural wealth in the plant and animal kingdoms is symbolized in Lesotho’s coat of arms, which is supported on either side by Basotho horses standing upon a terrace representing the Thaba Bosiu plateau, site of the ancient capital bearing the same name. At the center of the shield appears a crocodile, the emblem of the Basotho royal dynasty. At the base of the terrace, a ribbon displays the national motto in the Sesotho language: Khotso, Pula, Nala (Peace, Rain, Prosperity). In comparison, the Peruvian coat of arms also features representations of the country's wealth in the plant and animal kingdoms—along with the mineral kingdom—with both the vicuña and the cinchona tree, emblematic species of Andean origin.

LESOTHO

Source: istockphoto.com

TROUT

Source: istockphoto.com

ROASTED CHICKEN FEET AND GIZZARDS KEBABS

Source: istockphoto.com

KHEMERE (HOMEMADE GINGER DRINK)

Source: istockphoto.com

RECIPE TAMINA

Tamina is a traditional Algerian sweet, typically served to celebrate the birth of a child and during the Mouloud or Mawlid festival. It is made from toasted semolina mixed with honey and butter, often enriched with various spices and flavourings depending on the region. Decoration is an important part of its presentation, reflecting the creativity of each household.

INGREDIENTS:

- 500g semolina (medium or coarse varieties recommended)

- 250g butter

- 250g orange blossom honey (can be substituted with sugar syrup)

- 2–3 tablespoons orange blossom water

- 100g shredded coconut (optional)

- 1 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 100g Turkish halva

- Optional toppings (sugar pearls, ground cinnamon, toasted nuts, coconut, Turkish halva, etc.)

PREPARATION:

1. Melt the butter and honey in a pan over low heat. Remove from the heat and add the orange blossom water.

2. Toast the semolina in another pan over medium-low heat until golden (about 5 minutes, in batches if necessary).

3. Pour half of the toasted semolina into the honey and butter mixture and stir. Add the remaining half and mix well. The mixture should be liquid.

4. Crumble the Turkish halva into the mixture. Add half of the shredded coconut (if ussing) and stir.

5. Check the consistency; it should be smooth but slightly liquid. If it is too liquid, add the remaining coconut. If not using coconuts, let it rest for a moment, so it thickens.

6. Pour the Tamina onto a serving plate and decorate as desired.

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR AFRICA, THE MIDDLE EAST AND GULF COUNTRIES

CUMANANA XLIV – APRIL – 2025

Editorial Board

Ambassador Jorge A. Raffo Carbajal

Minister Marco Antonio Santiváñez Pimentel

Minister Counselor Eduardo F. Castañeda Garaycochea

Editorial Team

Ambassador Jorge A. Raffo Carbajal, Director General and Editor in Chief

First Secretary Dahila Astorga Arenas, Content Director

Third Secretary Giancarlo Martínez Bravo, English Edition Editor

Third Secretary Berchman A. Ponce Vargas, French and Portuguese Editions Editor

Gerardo Ponce del Mar, Layout Designer

Jr. Lampa 545, Lima, Peru

Phone: +51 1 204 2400

Email: peruenafrica@rree.gob.pe

Legal Deposit No. 2025-03899

ISSN: 3084-7583 (online)