INSIDE:

■ “Enchantments Emergency” - Alpine wilderness pays the price for agency neglect

■ “Luke Espinoza’s Story” - One firefighter’s mission to save irreplaceable ecosystems

■ “Oregon’s Wolf Recovery” - 25 years of conservation wins and setbacks

■ “Enchantments Emergency” - Alpine wilderness pays the price for agency neglect

■ “Luke Espinoza’s Story” - One firefighter’s mission to save irreplaceable ecosystems

■ “Oregon’s Wolf Recovery” - 25 years of conservation wins and setbacks

Base Camp evening programs are back! After a very successful second season in 2024, we’re very excited to bring back another season of events at the MMC for both the Mazamas and members of our community. In the spirit of community, Base Camp events are free of charge and open to all. A donation box will be available to support speaker travel. All Base Camp events are on Wednesdays from 6:30–8:30 p.m. unless noted otherwise.

Retired 40-year Denali Ranger Roger Robinson will compare the tragic 1954 first ascent of Denali’s South Buttress—where leader Elton Thayer died, prompting the mountain’s first helicopter rescue—with his own 1975 climb of the same route with OSU students. Robinson developed the Clean Mountain Can waste system and is featured in the 2017 book “Denali Ranger” by Lew Freedman.

No Man’s Land is an all-women + genderqueer adventure film festival celebrating non-male athletes in climbing and outdoor sports, hosted by She, They, Us—an inclusive Mazamas community for women, genderqueer, and gender non-conforming climbers. The evening features short films, runs 7–9 p.m. with intermission, and tickets are $20.

Anders Carlson and Megan Thayne will discuss Oregon’s rapidly retreating Cascade glaciers and introduce a new mobile app for citizen scientists to track glacier changes through repeat photography. Carlson founded the Oregon Glaciers Institute with 20+ years of cryosphere research experience, while Thayne leads the institute’s digital mapping and education programs.

Valerie Brown is founder of the “Embodied Intelligence Method™” who helps outdoor athletes move smarter and recover faster. This presentation covers recognizing early overtraining signs, nervous system recovery techniques, movement strategies for joint protection, and breathwork for managing stress to improve long-term performance and prevent injury.

The Siskiyou Mountain Film Tour features three new short documentaries about public lands across southwest Oregon and northwest California. Siskiyou Mountain Club is a nonprofit managing 400+ miles of trails in the region, using volunteers and staff who backpack to remote sites for trail maintenance, often in post-fire environments, plus fire lookout rebuilds and campground maintenance.

Volume 107 Number 5

September/October 2025

Bears Ears National Monument: A Mazama Outing Through Time, p. 14

Forest Service, In Crisis, Elevates Logging as its Sole Priority, p. 18

The Enchantments Emergency: A Case Study in Forest Service Collapse, p. 20

Taking on the Heat: The Story of Luke Espinoza, p. 22

Understanding Oregon’s Climate Future: An Expert Perspective from Dr. Paul Loikith, p. 24

Oregon’s Rainforest Reserve: A Story of Successful Community Conservation, p. 26

Twenty-five Years of Wolves in Oregon, p. 28

Why is Habitat Important? The Fight to Keep Protection in the Endangered Species Act, p. 32

Conservation Land Trusts: Building Bridges Between Communities and Conservation, p. 34

GlacierTracker: Turning Summit Snapshots into Citizen Science, p. 36

Finding Your Self to Find Your Way, p. 39

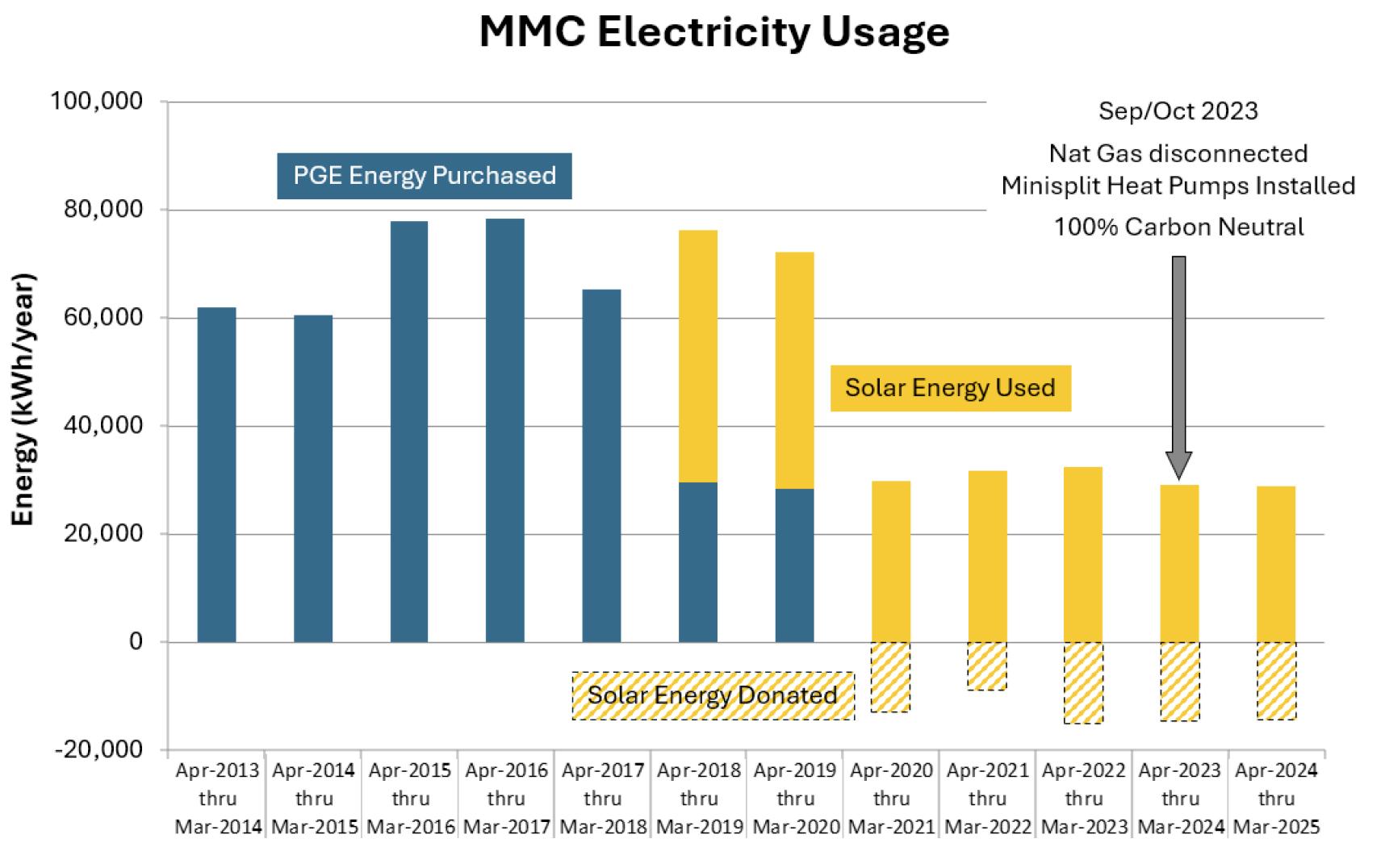

Five Years Carbon Neutral: MMC’s Solar Success Story, p. 40

Eight Books That Built Modern Mountaineering, p. 42

Mazama Base Camp Fall 2025 Program, p. 2

Executive Director’s Message, p. 4

Board of Director’s Message, p. 5

Upcoming Courses, Activities & Events, p. 8

Mazama Supporters, p. 10

Successful Climbers, p. 12

New Members, p. 13

Advanced Rock Wraps Up, p. 13

Critical INcident Stress Management Survey, p. 13

Looking Back, p. 16

Letter from the Editors, p. 17

Mazama Library, p. 46

Board of Directors Minutes, p. 47

Cover: Triptych of Creative Commons images.

Art work: Mathew Brock.

Above: A view of the Rainforest Reserve— which includes Onion Peak and parts of the Angora Peak Complex—from Ecola Point.

Photo: Justin Bailie.

“The multiple use mandate is being tossed aside like an empty bag of Cheetos by a careless hiker.” p. 18

“Climate change is contributing to a dramatic loss of our extreme cold, not an increase.” p. 24

Instead of thinking ‘this is a nice place to hike,’ I’d like to see more people think ‘this is an animal’s home.’” p. 28

Sometimes going out into nature is like visiting a sick friend; when we do that, we always feel better.” p. 39

by Jill Orr, Interim Mazama Executive Director

It’s a privilege to introduce myself as your Interim Executive Director. I joined the Mazamas in early August during a time of significant leadership transition, and I’m honored to help guide this remarkable organization through its next chapter. I also want to acknowledge and thank former Executive Director Rebekah Phillips for her leadership and for graciously meeting with me before her last day. While transitions can bring uncertainty, my promise to you is that I will care for the Mazamas and its people with the same dedication and respect for our mission that she did.

Since many of you may not know me yet, I thought I’d share a little about myself. I grew up in Iowa, where my love for the outdoors began long before I knew the word “conservation.” My childhood was filled with exploring trails in Hartman Reserve, riding bikes until dark, and catching lightning bugs (aka fireflies). As a Camp Fire Girl, I spent summer weeks at camp learning outdoor skills, paddling canoes (which became a favorite pastime with my father), and enjoying that mix of independence and belonging that comes from time in nature—long before the distractions of cell phones and social media. Those early experiences planted the seed for a lifelong love of nature and, eventually, my call to the West.

For more than two decades, I’ve worked with nonprofits in California, Colorado, and Oregon—helping them navigate change, foster inclusion, and deliver lasting impact. Here in Oregon, I’ve guided organizations through leadership transitions in fields ranging from food security and housing to foster care and youth arts programs. Before that, my work in museum education connected people of all ages with culture, creativity, and lifelong learning.

When I’m not working, you’ll most likely find me outdoors. I’m a lifelong athlete—cycling, running, swimming, hiking, and, more recently, backpacking in the Rockies thanks to my partner, Stan. In recent years, I’ve ventured into triathlons, earning my first 70.3 Ironman finish. The mountains, trails, and beauty of the Pacific Northwest are a big reason I chose to make Portland home with Stan, who teaches at Portland State University.

In the weeks and months ahead, my priorities as your interim ED will be:

■ Listening and learning – connecting with the board, staff, members, and volunteers to understand what’s working well, where there are challenges, and what matters most— while recognizing I won’t be able to meet with everyone individually.

■ Supporting our incredible staff –overseeing day-to-day operations, helping ensure programs, events, and our fundraising plan activities continue running smoothly during this transition.

■ Strengthening communication and alignment – working with board leadership to clarify roles between the board, staff, and volunteers, improve communication where possible, and maintain relationships with land managers.

■ Laying the groundwork for the future – assisting the board as needed and helping position the Mazamas for success with its next Executive Director, including onboarding support once that person is in place.

This issue of the Bulletin is devoted to conservation—a theme deeply aligned with our mission and personal to me. Every trail I’ve hiked, every mountain I’ve climbed (I can claim one 14er!), every alpine lake I’ve admired has been shaped by the choices of those who came before. We are the stewards for those who will come after. Whether it’s advocating for policy change, joining restoration projects, modeling Leave No Trace ethics, or making a financial contribution, each of us can help protect the places we love.

The outdoors doesn’t take care of itself—we have a part to play in keeping it healthy and worth coming back to. Sharon

The outdoors doesn’t take care of itself—we have a part to play in keeping it healthy and worth coming back to.

Selvaggio’s piece on the U.S. Forest Service urges us to watch policy shifts that could reshape our public lands. Suzanne Cable’s case study on the Enchantments shows the consequences when stewardship capacity is lost.

Other articles offer hope: Oregon’s Rainforest Reserve shows how communities can protect critical ecosystems; the GlacierTracker project invites us to turn summit photos into valuable data; and Jeff Hawkins’ look at five years of carbon neutrality at the Mazama Mountaineering Center proves conservation can be part of our daily operations.

As we navigate this transition together, I welcome hearing your ideas, concerns, and hopes for the Mazamas. I value your input and will be listening through the many conversations, events, and gatherings we share. This organization’s strength has always come from people like you—passionate, committed, and eager to both enjoy and protect our natural surroundings.

Thank you for welcoming me into this extraordinary community. I look forward to crossing paths with many of you—whether at the Center, on the trail, or in the pages of the next Bulletin.

by the Mazama Board of Directors

From our first steps on a forest trail, whether it’s the outset of a hike, the beginning of a trail maintenance project, or the pursuit of a summit, the Mazamas have always been guided by a simple truth: what we love, we protect. For more than 130 years, we have spoken up for the mountains and wild places that inspire us, and we have cared for them through hands-on stewardship. Our mission is guided by these values and our work is more important now than ever.

As we know, the natural environments we cherish face growing threats. Federal agencies charged with the oversight of public lands have seen resources cut, longstanding environmental safeguards have been rolled back, and designations that protect these lands are in danger. These changes affect the landscapes we enjoy, as well as the communities and ecosystems that depend on them.

The mountains are more than the rocky, snowy peaks we might see on the horizon.

For us, mountain environments are central to our community. Our advocacy and stewardship efforts, whether influencing policy, collaborating with conservation partners, or restoring damaged trails, are how we return a dividend to these places that give us so much.

Healthy ecosystems depend on diversity and balance, and so does a healthy Mazama organization. We must seek ways to diversify our revenue, create more ways for members to connect meaningfully, and ensure that volunteer roles remain rewarding. By aligning our internal health with the sustainable world we work to protect, we can strengthen our ability to advocate for and steward the mountains.

We invite every Mazama to join in this effort. Lend a hand on a stewardship project. Add your voice to an advocacy campaign. Join a climb, attend a program, or bring a friend into the community. Your energy, ideas, and commitment make us stronger.

While we continue this work, the Mazamas is navigating a critical transition with our organizational leadership. As of this writing, the Board of Directors is seeking a new Executive Director to engage our members, volunteers, staff, and outside partners to continue our journey into a sustainable and vibrant future. The 2025–2027 Route Ahead strategic plan continues

From trail to summit, the journey of the Mazamas has always been about more than reaching the top. It’s about protecting what we love, for today and for generations to come.

to serve as our compass, focusing us on the priorities that create a more substantial and more impactful future. To perform this search, a board and member-based hiring committee has been formed and is actively reviewing and interviewing candidates.

If you have comments or questions during our time of change, or have input or suggestions on how the organization could be more involved in advocacy and stewardship efforts, let us know at transition@mazamas.org. Your perspective matters.

From trail to summit, the journey f the Mazamas has always been about more than reaching the top. It’s about protecting what we love, for today and for generations to come. Together, we can ensure that the mountains, and the Mazamas, endure.

Above: Mazama work party on the Mazama Trail, July 10, 2025.

Photo: Nimesh Patel.

Thanks to the 686 current members and 138 nonmembers who shared invaluable insights into the Mazama experience. In addition to updated demographic data, the survey illuminated trends around why people join (or leave), what they value, and where they see room for growth. Here are a few early highlights:

Why people join (and why some leave)

The Mazamas empowers people to lead fuller outdoor lives—on their own, with friends, and within the organization. Most members join to learn new skills and find community. However, some members and nonmembers noted:

• Difficulty connecting or integrating

• Concerns about fairness and access to activities

• Lack of options for those with limited time or shifting interests

Nonmembers cite time, cost, and accessibility— not lack of interest—as barriers. Lapsed members primarily pointed to limited access and expressed lower regard for the organization overall.

The personal impact

Over 70% of members reported gains in physical and mental health, social connection, and appreciation for nature. More than 80% of volunteers and members under 30 also cited personal development and a stronger sense of belonging.

Opportunities by age group

Under 30s are enthusiastic, especially missionaligned, and eager for more field sessions and flexible learning formats. 50+ members want more peer-led activities and online instruction.

Education programs

All segments requested more hands-on learning, shorter courses, and skill-builder sessions. Instructors seek more training and clearer educational standards.

Volunteers

Highly committed, volunteers asked for a centralized system to find roles, track hours, and stay connected.

What members want

Over 200 comments surfaced four key needs:

• Better understanding of participant selection process

• Improved digital tools and infrastructure

• More affordable and accessible gear opportunities

• Stronger onboarding for newcomers

What’s next?

Leadership will explore these findings in more depth through summer focus groups. However, as a community, members are always encouraged to pursue opportunities and ideas— want to help? Get in touch!

We’re proud to share the 2024 Annual Impact Report, a comprehensive look at the year’s milestones, member engagement, and organizational growth. From welcoming over 640 new members to offering more than 700 volunteer-led activities, 2024 reflected our community’s deep commitment to adventure, education, and stewardship.

The report celebrates the 1,060+ individuals who advanced their outdoor skills through Mazama education programs, as well as the nearly 500 volunteers who made our programs possible. It highlights progress in inclusivity, conservation, and governance, along with new initiatives. You’ll also find highlights from community partnerships, grantmaking, risk management improvements, and our strategic priorities for 2025–2027.

Visit mazamas.org to read the full report, and learn how your support shaped a year of meaningful impact— and where we’re headed next!

Mazama Mountaineering Center 527 SE 43rd Ave., Portland, OR, 97215

Phone: 503-227-2345

Email: help@mazamas.org

Hours: Tuesday–Thursday, 10 a.m.–4 p.m.

Mazama Lodge

30500 West Leg Rd., Government Camp, OR 97028

Hours: Closed

Editor: Mathew Brock, Bulletin Editor (mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org)

Members: Darrin Gunkel, chair; Patti Beardsley, David Bumpers, Theo Cantalupo, Aimee Frazie, Brian Hague, Owen Lazur, Ryan Reed, Michele Scherer Barnett, Jen Travers. (publications@mazamas.org)

MATHEW BROCK

Director of Special Collections and Media Mazama Bulletin Editor mathew@mazamas.org

RICK CRAYCRAFT Building Manager facilities@mazamas.org

EMILY FASNACHT

Finance & Administration Manager emilyfasnacht@mazamas.org

JILL ORR

for the love of the mountains

Learn more about how you can integrate charitable giving to support the Mazamas.

Whether you’re considering a bequest in your will, setting up a charitable remainder trust, or exploring other options, by including a planned gift in your legacy, you’ll secure our continued success while ensuring that your passion endures for generations to come.

If you’ve already decided to include the Mazamas in your estate plans, we invite you to let us know. You’ll want to be sure that you’ve recorded the Mazamas with the Tax ID (EIN) 93-0408077.

Even ordinary people can make an extraordinary difference.

CONTACT US: Lena Toney, Development Director 971-420-2505 | lenatoney@mazamas.org

Interim Executive Director jillorr@mazamas.org

BRENDAN SCANLAN Operations & IT Manager brendanscanlan@mazamas.org

LENA TONEY Development Director lenatoney@mazamas.org

For additional contact information, including committees and board email addresses, go to mazamas.org/contactinformation.

MAZAMA (USPS 334-780):

Advertising: mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org. Subscription: $15 per year. Bulletin material must be emailed to mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org.

The Mazama Bulletin is currently published bi-monthly by the Mazamas—527 SE 43rd Ave., Portland, OR 97215. Periodicals postage paid at Portland, OR. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to MAZAMAS, 527 SE 43rd Ave., Portland, OR 97215. The Mazamas is a 501(c)(3) Oregon nonprofit corporation organized on the summit of Mt. Hood in 1894. The Mazamas is an equal opportunity provider.

Date: Wednesday, December 3, 2025

Time: 6–8 p.m.

Location: Nordic Northwest

The Mazamas has hundreds of volunteers, and many have given their time, talent, and expertise for decades. In any given week, they are lecturing, leading climbs, taking people on hikes and rambles, strapping on skis, strategizing about conservation, and more.

The organization could not function without our volunteers, and we can’t wait to honor them. Please mark your calendars and join us for this year’s Volunteer Appreciation Night Wednesday, December 3 at Nordic Northwest in southwest Portland. It’s a night of celebration with great appetizers, drinks, and company. We’ll be unveiling the winners of our prestigious service awards and the newly elected 2026 Board of Directors!

This event is made possible by a generous bequest from Yun Long Ong, whose love for the Mazamas called him to lead climbs on all 16 peaks.

Are you ready to glide into winter fun? Mark your calendars for our upcoming Nordic Ski School Info Night on Wednesday, October 29 at 7 p.m.

Join us to discover everything you need to know about our January–February cross-country skiing classes. Whether you’re a beginner eager to learn or looking to enhance your skills, this info session is perfect for you. We’ll cover essential topics like selecting the right class level, understanding equipment needs, and answer all your questions in an interactive Q&A.

Registration opens in late October, so don’t miss this chance to meet fellow skiing enthusiasts and prepare for an amazing winter on the trails. Get ready to embrace the snow and think Nordic!

Watch the weekly eNews and the Mazama calendar for exact dates and registration details.

Have you considered becoming a Stop the Bleed (STB) instructor? The Mazama First Aid Committee is looking to expand our first aid skill-builder mini-course offerings. The Mazamas recently applied to become a national STB education center and are applying for an STB instructional material grant. Having more STB instructors and more classes helps with our application and provides a community benefit. Goto www.bit.ly/MazFASTB and see if you are eligible to become an STB instructor. The list of eligible health care and non-health professionals includes WFR, Ski Patrol, OSHA instructors, lifeguard, dietician, pharmacist, and law enforcement, to name a few. If you check your eligibility and are committed to becoming an STB instructor, send an email to firstaid@mazamas.org. Thank you for considering becoming a part of the Mazama First Aid community!

Help us reduce our environmental footprint by opting out of receiving the printed Mazama Bulletin. By choosing the digital-only version, you'll:

■ Save trees and reduce paper waste

■ Decrease carbon emissions from printing and shipping

■ Access the same great content instantly on any device

■ Support our commitment to responsible environmental stewardship

The digital Bulletin offers enhanced features like searchable text, clickable links, and high-resolution photos while helping preserve the natural spaces we all cherish.

Ready to make the switch?

Simply visit tinyurl.com/ MazBulletinOptOut. Thank you for helping us protect the environment we love to explore.

We envision a vibrant, inclusive community united by a shared love for the mountains, advocating passionately for their exploration and preservation.

INCLUSION

We value every member of our community and foster an open, respectful, and welcoming environment where camaraderie and fun thrive.

SAFETY

We prioritize physical and psychological safety through training, risk management, and sound judgment in all activities.

EDUCATION

We promote learning, skillbuilding, and knowledgesharing to deepen understanding and enjoyment of mountain environments.

SERVICE

We celebrate teamwork and volunteerism, working together to serve our community with expertise and generosity.

SUSTAINABILITY

We champion advocacy and stewardship to protect the mountains and preserve our organization’s legacy.

Building a community that inspires everyone to love and protect the mountains.

We gratefully acknowledge contributions received from the following generous friends between May 1, 2024 – May 15, 2025. If we have inadvertently omitted your name or listed it incorrectly, please notify Lena Toney, Development Director, at 971-420-2505.

Anonymous (27)

David W Aaroe and Heidi A Berkman

Patricia Akers

Louis Allen

Stacy Allison

Jerry O Andersen

Dennis H Anderson

Edward L Anderson

Peggy B Anderson

Justin Andrews

Alice Antoinette

Carol M Armatis

Jerry Arnold

Kamilla Aslami

Chuck Aude

Brad Avakian

Gary R Ballou

Tom Bard

Dave Barlow

Jerry E Barnes

Michele Scherer Barnett

John E Bauer

Scott R Bauska

Tyler V Bax

Larry Beck

Steven Benson

Daven Glenn Berg

Erwin Bergman

Bonnie L Berneck

Bert Berney

Joesph Bevier

Rachel Bieber

Ken and Nancy Biehler

James F Bily

Pam J. Bishop

Gary Bishop

Bruce H Blank

Anna N. Blumenkron

Peter Boag

Tom G Bode

Andrew Bodien

Barbara Bond

Mike Borden

Jeffrey F Boskind

Brookes Boswell

Steve Boyer

Bob Breivogel

Rex L Breunsbach

Scott P. Britell

Alice V Brocoum

Elizabeth Bronder

Richard F Bronder

Amy Brose

Jann O Brown

Anna Browne & Barry Stuart

Keller

Barry Buchanan

Carson Bull

Eric Burbano

Joel Burslem

Rick Busing

Neil Cadsawan

Keith Campbell

Patty F Campbell

Ann marie Caplan

Jeanette E. Caples

Riley Carey

Kenneth S Carlson

Emily Carpenter

John D Carr

Ken Carraro

Marc Carver

Jacob Case

Susan K Cassidy

Rita Charlesworth

Nancy Church

Catherine Ciarlo

Max Ciotti

Matt Cleinman

William F Cloran

Kathleen Cochran

Jeff Coffin

Carol Cogswell

Justin (JC) Colquhoun

Charles Combs

Kristy J Comstock

Brendon Connelly

Toby Contreras

Elisabeth (Lis) Cooper

Patti Core Beardsley

Dylan Neil Corbin

Doug Couch

Lori Coyner

Darrel M Craft

Adam Cramer

Rick Craycraft

Mark Creevey

Cynthia Cristofani

Tom F Crowder

Liz A. Crowe and Grant Garrett

George Edward Cummings

Julie Dalrymple

Teresa L. Dalsager

Ellen Damaschino

Gail Dana-Sheckley

Alexander S. Danielson

Betty L Davenport

Larry R. Davidson

Tom E Davidson

Howie Davis

Chris Dearth

Edward Decker

Alexander Dedman

Richard G Denman

Sumathi Devarajan

Brad Dewey

Donald Keith Dickson

Sue B Dimin

Jonathan Doman

MaLi Dong

Mark Downing

Robyn Drakeford Wonser

Keith S Dubanevich

Deborah Driscoll

Keith S Dubanevich

Debbie G. Dwelle & Kirk

Newgard

Richard R Eaton

Heather and Joe Eberhardt

John Egan

Rich Eichen

Toni Eigner

Donna Ellenz

Kent Ellgren

Roland Emetaz

Becky Engel

Mary L Engert

Stephen R Enloe

Bud Erland

Kate Sinnitt Evans

Shelley Everhart

Joshua Ewing

John Facendola

William F Farr

Patrick Feeney

Travis Feracota

Darren Ferris

Aimee Diane Filimoehala

Lilie Chang Fine

Jonathon Fisher

Steven Fisher

Erin Fitzgerald

Ben Fleskes

Peter C Folkestad

Diana Forester

Caroline Foster

Dyanne Foster

Mark Fowler

Joe Frank

Daisy A. Franzini

Aimee Frazier

Michael C. French

Trudi Raz Frengle

Ardel Frick

Jason Fry

Suzanne Furrer

Brinda Ganesh

Matthew Gantz

Becky Garrett

Kevin Gentry

Paul R Gerdes

Pamela Gilmer

Lise Glancy

Drew Glassroth

John Godino

Zoe Goldblatt

Richard Goldsand

Sandy Gooch

Diana Gordon

Michael Graham

Ali Gray

Dave M Green

Kanjunac Gregga

Shannon Hope Grey

Loren M. Guerriero

Tom & Wendy Guyot

Jacob Wolfgang Haag

Jeff L Hadley

Dan Hafley

Sohaib Haider

Noma L Hanlon

Martin Victor Hanson

Terrance Heath Harrelson

Brook B. Harris

Duncan A Hart

Freda Sherburne & Jeff

Hawkins

Marcus Hecht

Lisa Hefel

Amy Hendrix

Gary Hicks

Elizabeth Hill

Marshall Hill-Tanquist

Maurene Hinds

Natasha Hodas

Frank Hoffman

Gregg A Hoffman

Rick Hoffman

Sue Holcomb

Lehman Holder

Mike Holman

Kris Holmes

Patty H Holt

Steven Hooker

Michael Hortsch

Charles R Houston

Hal E Howard

Nathan Howell

John A Hubbard

Flora Huber

Chip Hudson

Valoree Hummel

Michael Hynes

Kirsten Jacobson

Rahul Jain

Irene M James-Shultz

Chris Jaworski

Scott Jaworski

Joanne Jene

Brita Johnson

Megan Johnson-Foster

Truth Johnston

Greg J. Jones

Mark Jones

Thomas Jones

Julia Jordan

Nathan Kaul

George Alan Keepers

Joe Kellar

Jill Kellogg

Shawn Kenner

Charles R Kirk

Sergey Kiselev

Ray Klitzke

Dana S. Knickerbocker

Susan E Koch

Craig Koon

Chris Kruell

Barbara N Kuehner

Martin Kreidl

Dennis V Kuhnle

Cathy Kurtz

Lori S LaDuke

Richard A LaDuke

Lori A Lahlum

Brenda Jean Lamb

Carol Lane

Jackson Lang

Donald E Lange

Barbara Larrain

Sándor Lau

Nathan Laye

Thuy Le

Petra D LeBaron-Botts

Seth Leonard

Diane M. Lewis

Ernest (Buzz) R Lindahl

Jason N. Linse

Natalie Linton

Margery Linza

Jacob Lippincott

Jeff Litwak

Craig H Llewellyn

Vlad Lobanov

Robert W Lockerby

Christie Lok

Meredith K. Long

Bill E. Lowder

John L MacDaniels

Alexander L. Macdonald

Joan MacNeill

Patti Magnuson

Ted W Magnuson

Barbara Marquam

Bartholomew “Mac” Martin

Bridget A Martin

Ted and Kathryn Maas

Laurie Mapes

Larry G Mastin

James Mater

Donald C. Mather

Allan McAllister

Adam Marion

Robert A McClanathan

Margaret McCue

Mike McGarr

Jamie K. McGilvray

Reed Davaz McGowan

Wesley McNamara

Wilma McNulty

Melanie Means

Jeff I Menashe

Forest Brook MenkeThielman

George T. Mercure

Barbara A Meyer

Daniel J Mick

Dick Miller

James (Jim) Miller

Thomas M. Miller

Sarah A Miller

Keith Mischke

Gordy James Molitor

Michael Jeffrey Mongerson

Mary Monnat

Alex Montemayor

Yukiko Morishige

Joanne Morris

Ryan Morrow

Kristen Mullen

Dawn Murai

Megan Nace

Cheryl Nangeroni

Stephan P. Nelsen

Rachael Nelson

David L Nelson

Leah Nelson

Veronika and Jerry Newgard

John Niemeyer

Kae Noh

Cait Norman

Patricia M Norman

Ray North

Jim Northrop

Andy A. Nuttbrock

Jennifer Oechsner

Christine Olinghouse

Kathy Olson

Michael Olson

Jim Orsi

Kim Osgood

Nell Ostermeier

Brent Owens

John B Palmer

Alan James Papesh

Jooho Park

Nimesh “Nam” Patel

Kellie Peaslee

Ryan Peterson

Phillip Petrides

Theo Pham

Rebekah Phillips & Lars

Campbell

Cindy L Pickens

Robert T Platt

Judith Platt

Steve Polansky

Richard Pope

David Posada

Bronson Potter

Atalanta Powell

Devyn W Powell

William J. Prendergast

Morgan Prescott

Rosemary Prescott

Joe Preston

Frances Prouse

Walker Pruett

Emily Grace Pulliam

Michael Quigley

Sarah Raab

Kathy Ragan-Stein

Sandy Ramirez

Cullen Raphael

Walter Raschke

Rahul K Ravel

Stacey M. Reding

Ally Reed

Elizabeth Reed

Ryan Reed

Steph Reinwald

Kristina Rheaume

Anne Richardson

Judy Ringenson

Gary T Riggs

Lisa F Ripps

Echo River

Andy Robbins

Reigh Robitaille

Margaret Rockwood

Jeffery V. Roderick

David Roethig

Kirk C. Rohrig

John Rowland

Steven Ruhl

Gerald Runyan

Mark R Salter

Ellen Satra

Janice E Schermer

Liz Schilling

Bill Schlippert

Janice Schmidt

Ron Schmidt

Michael Schoenheit

Caleb Schott

Donna Schuurman

Leigh Schwarz

Diana R Schweitzer

Colby Schweitzer

Greg A Scott & Bonnie

Paisley Scott

Marty Scott

Tim Scott

James E Selby

Astha Sethi

Lucy Shanno

Roger D Sharp

Shahid Sheikh

Joanne Shipley

Rob Shiveley

Richard B Shook

Gary Shumm

Ellen P. Simmons

Patricia Ann Sims

Liz Sinclaire

Suresh P Singh

Jeanine Sinnott

Joan D Smith

Rachel Smith

Joseph Hoyt Snyder

Monica Solmonson

Dorothy Sosnowski

Cassie Soucy

Mark Soutter

Carrie Spates

Tony and Mary F Spiering

Tullan Spitz

Mark S Stave

Paul Steger

Bill Stein

Steve Stenkamp

John Sterbis

Lenhardt Stevens

Lee C. Stevenson

Scott Stevenson

John Stewart

Linda Stoltz

George Stonecliffe

Peter W Stott

Celine T Stroinski

Lawrell Studstill

Carol Stull

MaryAnn Sweet

Roger W Swick

Heidi Tansinsin

John G Taylor

Claire Tenscher

Ned Thanhouser

Amanda Carlson Thomas

Jodi Thompson

Lena Toney

Jen Travers

Seth Truby

Gerry Tunstall

Kenneth Umenthum

David A. Urbaniak

Katrin Valdre

Stephen A. Wadley

Harlan D Wadley

Jean Waight

Benjamin Ward

Cheryl L Weir

Donald G Weir

Dick B Weisbaum

William B Wells

Steve Wenig

Jeffrey W Wessel

Joe Westersund

Guy Wettstein

James P Whinston

Brian White

David White

Joe Whittington

Robin A Wilcox

Gordon Wilde

Debra A Wilkins

Thomas J. Williams

Scott C Willis

Harry Wilson

Richard Wilson

Fendall G Winston

Verena Winter

David Winterling

Gordy Winterrowd

Ingeborg Winters

Liz Wood

Joanne Wright

Jordan Young

Cam (Caroline) M Young

Roberta Zouain

Jason Zuchowski

IN MEMORIAM

In honor of Yun Long Ong for his love of mountains and enthusiastic dedication to the Mazamas, from his husband and fellow Mazama, Bill Bowling.

Katie Barker, by Charles and Louis E Barker

Fred Blank, by Bruce H

Blank

Edith Clarke, by Joesph

Bevier

Jane Dennis. A dear friend & outdoor companion who has

passed away 3 yrs ago., by Robyn Drakeford Wonser

Brian Holcomb, by Sue Holcomb

Werner & Selma Raz, by Trudi Raz Frengle

Jeff Skoke, by Seth Truby

Ray Mosser, by Keith Mischke

David Schermer, by Janice E Schermer

Will Hough, by Zoe Goldblatt

Will Hough, by Maurene Hinds

Elva Coombs, by Joanne Shipley

Martin Hanson, by Steven Bensen & Lisa Brice

Happy belated birthday, Greg Scott!, by Deborah Driscoll

Rodney Keyser, by William J. Prendergast

Greg Scott, by Anonymous

Ray Sheldon, by Mary F Spiering

Rocky Shorey, by Susan E Koch

Cecilia M, by Jason Zuchowski

George Sweet, by MaryAnn Sweet

Anthony Wright, by Joanne Wright

Robert Skeith Miller, by James (Jim) Miller

Ralph & Ellen Core, by Patti Core Beardsley

My mom, Jean Fitzgerald, by Erin Fitzgerald

Krista and Neil, by Sara A Miller

Kevin Mischke, by Brian White

Andrew Robin, by Tullan Spitz

Sharon Herner, by Reed Davaz McGowan

Jean Fitzgerald, by Louise Allen

IN-KIND DONATIONS

Anonymous

Bob Breivogel

Liz A. Crowe and Grant Garrett

George Cummings

Debbie G. Dwelle

Kate Sinnitt Evans

Armin Furrer Family

Peter and Mary Green

Tom & Wendy Guyot

Martin Victor Hanson

Duncan A Hart

Jeff Hawkins

Mike Holman

Chris Jaworski

Eric Jones

David L Nelson

Alan & Kristl Plinz

Elizabeth Reed

Richard Sandefur

Greg A Scott

John Sheridan

Steve Stenkamp

Claire Tenscher

Lena Toney

David A. Urbaniak

William B Wells

Owen Wozniak

Margaret Zimmermann

CORPORATE SUPPORT & MATCHES

Abbott Apple

Applied Materials

Autodesk

Benevity Community Impact Fund

Broadcom

CGC Financial Services LLC

Ebay, Inc.

Edward Jones

Elasticsearch

Glacier House

Intel

KEEN

Lam Research

McKinstry Charitable Foundation

Microsoft

Nike

Oakshire Beer Hall

Household

Paypal Giving Fund

Portland General Electric

Ravensview Capital Management

Rock Haven Climbing

Springwater Wealth Management

The Standard Timberline Lodge

Wildflower Meadows, LLC

CORPORATE IN-KIND

Arkangel Technology Group

Better Bar

Broadway Floral and Gifts

Five Stakes

Johns Marketplace

Never Coffee Lab

Mountain Shop

Portland Syrups

Trailhead Coffee Roasters

Westward Whiskey

Jun 1, 2025-Castle/Pinnacle, Standard/East Ridge. Janelle M Klaser, Leader; Kelsey Sullivan, Assistant Leader. James Jula, Assistant Leader. Colin Baker, Jacy Clare, Donald Kennard, MaryBeth Morris, Frank Squeglia, John Sullenbarger, Kylie Wells.

Jun 1, 2025-Unicorn Peak, Snow Lake. Ann Marie Caplan, Leader; Kyle Tarry, Assistant Leader. Saad Ahmed, Alex Brauman, Shelby Eagleburger, Lilie Chang Fine, Kristen Frank, Zach Green, Moinul Mahdi, Jordan Reaksecker, Ellen Satra.

Jun 1, 2025-South Sister, Devil’s Lake Ski/Board Tour. Nimesh Patel, Leader; Scott Nasello, Assistant Leader. Stephen Schutts, Assistant Leader. Michele Barnett, Stefan Butterbrodt.

Jun 2, 2025-Mt. Hood (Wy’east), South Side. Lynne Pedersen, Leader; Sergey Kiselev, Assistant Leader. Justin Bourne, Liz Hamilton, William Kazanis, Sean Knight, Mi Lee, Elizabeth Reed.

Jun 3, 2025-Mt. Hood (Wy’east), South Side. Gary Bishop, Leader; Jen Travers, Assistant Leader. Finn Ramos, William Withington.

Jun 4, 2025-Mt. Hood (Wy’east), South Side. Tim Scott, Leader; Astrid Zervas, Assistant Leader. David Bumpus, Seth Dietz, Charlie Guidarini, Isabelle Kennedy, Kaitlyn Klein, Heather Nesheim, Gregory Schrupp, Edward Stratton, Gus Swanson, Syringa Volk.

Jun 7, 2025-Unicorn Peak Climb. Carol Bryan, Leader; Lynne Pedersen, Assistant Leader. Samantha Dowgin, Brandon Hopkins, William Kazanis, Mi Lee, Kristine de Leon, Gregory Schrupp.

Jun 7, 2025-Middle Sister, Hayden Glacier, North Ridge. Duncan Hart, Leader; Richard Hall, Assistant Leader. Michele Scherer Barnett, Alex Cant, Mark Creevey, Milton Diaz, Kaitlyn Klein, Evan McDowell, Elise Rupp, Tanvi Singh, Jordan Williams.

Jun 8, 2025-Unicorn Peak, Snow Lake. Guy Wettstein, Leader; Theo Pham, Assistant Leader. Jon Brown, Mike Harley, Isabelle Kennedy, Jackson Lang, Natalie Linton, Grant Stanaway.

Jun 11, 2025-Mount St. Helens, Swift Creek Worm Flows. Marty Scott, Leader; Shirley Welch, Assistant Leader. Kaitlyn Klein, Seth Leonard, Rebekah Phillips, Scott Stevenson, Gus Swanson.

Jun 12, 2025-Mt. Ellinor, SE Chute. Judith Baker, Leader; Kshitij Kulkarni, Alex Kunsevich, Jonathan Llindgren, Logan Mante, Briana Pavlich.

Jun 13, 2025-Middle Sister, Hayden Glacier, North Ridge. Jen Travers, Leader; Matthew Gantz, Assistant Leader. Allison Boyd, Ali Gray, Scott McClure, Melanie Means, Maddy Otto, Andy Veenstra.

Jun 14, 2025-Unicorn Peak, Snow Lake. Tim Scott, Leader; Evan McDowell, Assistant Leader. Isabel Arnold, Daniel Bryan, David Bumpus, Sarah Dugan, Zachary Homen, Frank Liao, Natalie Rowell, Quinn Schwartz, Nikki Thompson, Richard Zheng.

Jun 14, 2025-Eagle, Chutla, Wahpenayo. Greg Scott, Leader; Patricia Akers, Assistant Leader. Paxton Alsgaard, Seth Leonard, Alex Montemayor, Gabriela Sisco, Gus Swanson, Kathryn Villarreal, Syringa Volk.

Jun 15, 2025-Pinnacle Peak, East Ridge. Tim Scott, Leader; Patricia Akers, Assistant Leader. Isabel Arnold, Daniel Bryan, David Bumpus, Sarah Dugan, Zachary Homen, Frank Liao, Natalie Rowell, Quinn Schwartz, Nikki Thompson, Richard Zheng.

Jun 15, 2025-Middle Sister, Hayden Glacier, North Ridge. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Brian Bizub, Matthew Delgado, Phil Fargason, Matthew Gordon, Matthew Haglund, Alyssa Koida, Emily Kramer, Nisha Krishnan, Alex Mechler-Hickson, Joe Robinson.

Jun 15, 2025-Unicorn Peak. Greg Scott, Leader; Evan McDowell, Assistant Leader. Paxton Alsgaard, Seth Leonard, Alex Montemayor, Gabriela Sisco, Gus Swanson, Kathryn Villarreal, Syringa Volk.

Jun 15, 2025-The Castle, Standard Route. Tim Scott, Leader; Patricia Akers, Assistant Leader. Isabel Arnold, Daniel Bryan, David Bumpus, Sarah Dugan, Zachary Homen, Frank Liao, Natalie Rowell, Quinn Schwartz, Nikki Thompson, Richard Zheng.

Jun 16, 2025-Mt. Shasta, Hotlum Bolam Glacier. Darren Ferris, Leader; Heather Nesheim, Assistant Leader. Daven Glenn Berg, Zack Crandell, Becca Hawkins, Del Profitt, Mark Stave, Astrid Zervas.

Jun 17, 2025-Mt. Shasta, Avalanche Gulch, Ski Climb. Forest Brook MenkeThielman, Leader; Matt Mudrow, Assistant Leader. Milton Diaz, Lucas Illing, Evan Sloyka.

Jun 22, 2025-Mt. Thielsen, West Ridge/ Standard Route. Matthew Sundling, Leader; Janelle Klaser, Assistant Leader. Benjamin Briscoe, Dylan Neil Corbin, Lydia Hernandez, Chase Verbout.

Jun 24, 2025-Mt. Ellinor. Sue B Dimin, Leader; Linda Blake, Rick Busing, Bruce Giordano, Kayla Miles, Kellie ODonnell, Diane Peters, Echo River, Donna Vandall.

Jun 27, 2025-Mt. Shasta, Clear Creek. Gary Bishop, Leader; Neil Connolly, Assistant Leader. Ian Edgar, Anna Lio, Michelle Martin, Evan McDowell, Beatrice M. Robinson.

Jun 28, 2025-Mt. Adams, South Side. Kevin Ritscher, Leader; Janelle Klaser, Assistant Leader. Andy Hargis, Anthony Hayes, Sharon Jones, Matthew Meyer, Audrey De Paepe, Scott Stevenson.

Jun 28, 2025-Mt. Rainier, Kautz Glacier. Ryan Reed, Leader; Bikash Padhi, Assistant Leader. Agreen Ahmadi, Byung Gi Han, Kyle Mangione.

Jul 4, 2025-Mt. Baker, Easton Glacier. Guy Wettstein, Leader; Alicia Antoinette, Assistant Leader. Allison Boyd, Corey Johns, Scott McClure, Heather Nesheim, Colleen Rawson, Scott Stevenson.

Jul 5, 2025-Mount St. Helens, Monitor Ridge. Gary Bishop, Leader; Brad Dewey, Assistant Leader. Lindsay Ang, Jacy Clare, Isabelle Ehlis, Matthew Pittman, Ryan Popma, Echo River, Alison Roberts, Julia Ronlov.

Jul 6, 2025-Mt. Olympus, Blue Glacier. Darren Ferris, Leader; Matthew Gantz, Assistant Leader. Erin Courtney, Leana Goetze, Jonathan Lawrence Hart, Petra LeBaron-Botts, Joe Robinson, Edward Stratton.

Jul 13, 2025-Mt. Aix, Nelson Ridge. Bill Stein, Leader; Amanda Lovelady, Assistant Leader. Mee Choe, Mario DeSimone, David J McDonald, Ellen Satra, Kristofel Simbajon, Tim Spengler, Shelley Stearns.

Jul 13, 2025-Beacon Rock Southeast Corner. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Prajwal Mohan, Assistant Leader. Brian Bizub, Alex Mechler-Hickson.

Jul 14, 2025-Mt. Rainier, Disappointment Cleaver. John Sterbis, Leader; Thomas Clarke, Assistant Leader. Read Caulkins, Lorena Caulkins.

Jul 18, 2025-Mt. Olympus, Blue Glacier. Gary Bishop, Leader; Laetitia Ma. Pascal, Assistant Leader. Ian Edgar, Matthew Graham, Kyla Skerry.

Between June 1, 2024, and July 31, 2025, the Mazamas welcomed 63 new members. Please join us in welcoming them to our community!

Turtle Ala

Michael Archer

Jimmy Baker

Al Bevacqua

Mamta Bhargava

Marc-Alexander

Blassnig

Philip Coufal

Benjamin Crockett

Emily Davis

Josh Deleon

Kyle DeMarco

Micah Dickinson

Jason Edwards

Isabelle Ehlis

James Falkner

John Fischer

Lindsay Fredrickson

Jason Fry

Bryan Gillespie

Max Goldsmith

Yon Gomez

Charles Gray

Tyler Guzman

Gary Harland

Alyssa Hausman

Randy Hestand

Elias Hestand

Jon Hixon

Reed Hooke

Claire Jouseau

Rakhsha Khani

Andrzej Kozlowski

Caira Lessick

Nicholas Lim

Alexander Long

Rhonda MacAllister

Quinne MacAllister

Eustacia MacAllister

Patrick Maddox

Nicole McCallum

Kimberly Mckeown

Angela Merritt

Joshua Meyers

Bumsoon Park

Kendall Parks

Alyssa PerdomoHazen

Antoinette Pietka

George Pulliam

James Rankin

Ruth Rice

Jeri Richard

Irene Robinson

Andrew Robinson

Shana Savikko

Aubrey Sharwarko

Caitlin Shrigley

Kathryn Stocking

Kirstin Thompson

Dahlia Ugarte

Chase Verbout

Andrea Ward

Alden Wessel

Mike Wiegand

Jul 19, 2025-Mt. Pugh, NW Ridge. Bill Stein, Leader; Amanda Lovelady, Assistant Leader. Nicole Egeler, Lydia Hernandez, Sara Elizabeth Jensen, Briana Pavlich, Ryan Popma.

Jul 19, 2025-Sahale Mountain. Jeffrey Welter, Leader; Milton Diaz, Winnie Dong, Martin Fisher, Charlie Guidarini, Alex Kunsevich, Hariank Mistry, Elizabeth Reed.

Jul 20, 2025-Mt. Jefferson, South Ridge. Tim Scott, Leader; Ryan Zubieta, Assistant Leader. Saad Ahmed, Jocelyn Alyse Brackney, Brad Dewey, Matt Egeler, Becca Hawkins, Walker McAninch-Runzi, Martin Taylor, Leesa Tymofichuk, Sabrina Wolfe, Astrid Zervas.

by Advanced Rock Committee

And that's a rap! On May 20, 2025, a class of 26 students celebrated their last lecture of Advanced Rock. This crew put in serious work, anchored their technical rock skills both in and out of the Mazama Mountaineering Center. Through many lectures and field sessions, they never stopped belay-ving in themselves and stayed calm when the weather got a little

Have you participated in a CISM debriefing in the past? If so, please consider sharing about your experience of the debriefing process through this brief anonymous survey. Your input will help the Critical Incident Stress Management committee better understand what members value about our work and how we can improve the service we offer.

The survey can be accessed by viewing and tapping the QR code on the right using your smartphone's camera app. Feel free to email cism@ mazamas.org with any questions or comments about the survey.

Jul 25, 2025-Pyramid Peak, Standard. Jen Travers, Leader; Melanie Means, Beatrice Robinson, Astrid Zervas.

Jul 26, 2025-The Tooth. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Agreen Ahmadi, Assistant Leader. Stefan Butterbrodt, Omar Najar.

Jul 26, 2025-Copper and Iron, Tahoma Creek. Jen Travers, Leader; Beatrice M. Robinson.

Jul 27, 2025-Sloan Peak, Corkscrew Route. Tim Scott, Leader; Evan Conway Smith, Assistant Leader. Seth Dietz, Leana Goetze, Ali Gray, Nimesh Patel, Kevin Ritscher.

nuts. We're excited for them to return next year to mentor the next generation of climbers.

A huge thank you to all our assistants. We could NOT do this without you! We truly appreciate the time and energy it takes to assess gear placements, anchors, develop, give a lecture, or climb Cinnamon Slab for the n-th time.

Jul 27, 2025-Mt. Olympus, Blue Glacier. Guy Wettstein, Leader; Sabrina Wolfe, Assistant Leader. Allison Boyd, Elena Ivanova, Scott McClure, Evan McDowell, Tyler Sievers, Leesa Tymofichuk.

Jul 28, 2025-Mt. Triumph, NE Ridge. Darren Ferris, Leader; Ryan Reed, Assistant Leader. Drew Dykstra, Alexander Macdonald.

Jul 29, 2025-Pinnacle Peak, East Ridge. Mark Stave, Leader; Alex Breiding, Truth Johnston, Alyssa Koida, Emily Kramer, Seth Leonard, Kayla Miles, Linda Musil, Kelly O’Loughlin.

by Bob Breivogel, Outing Committee Co-chair

Agroup of Mazamas explored a remote part of southern Utah for ten days in April 2025. Starting in Salt Lake City, we traveled to Moab, Bluff, and Blanding. The prime focus was Bears Ears but we also hiked in Arches National Park and Natural Bridges National Monument.

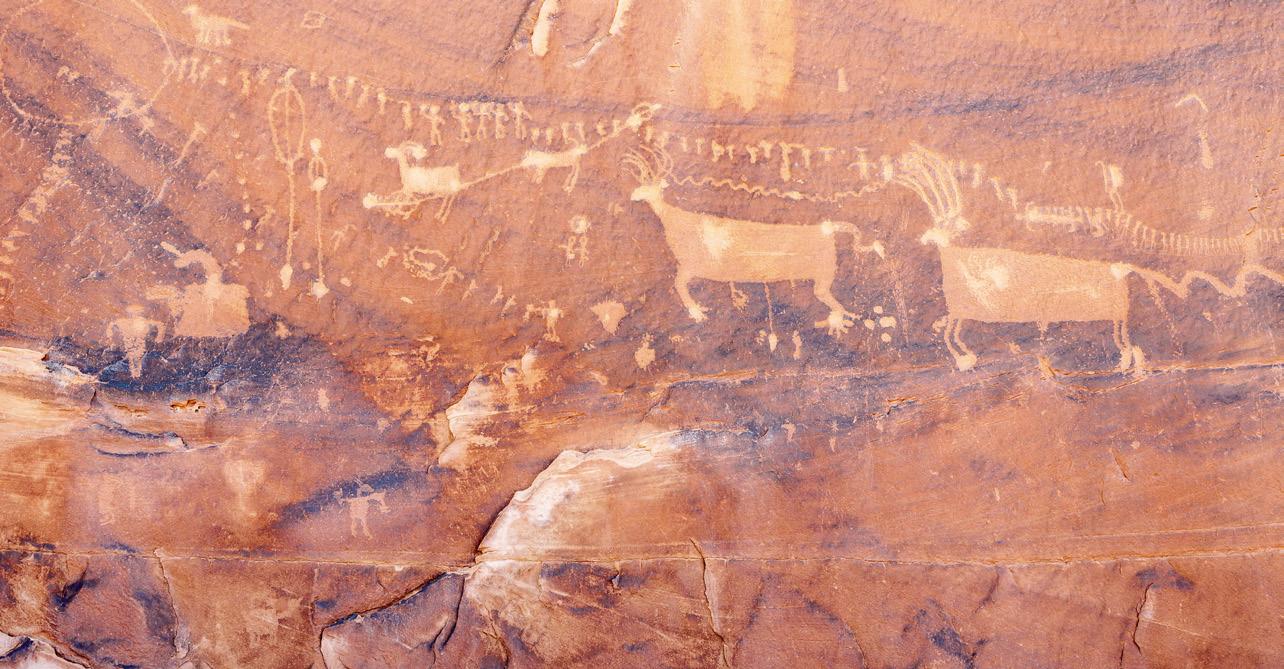

Bears Ears is a newer national monument, created by President Obama in 2016. It preserves the land where, for hundreds of generations, native peoples lived in the deep sandstone canyons, mesas, and mountaintops; it is one of the densest and most significant cultural landscapes in the United States. Abundant rock art, ancient cliff dwellings, ceremonial sites, and countless other artifacts provide an extraordinary archaeological and cultural record of 700–1000 years ago.

Bears Ears National Monument has been controversial and has been reduced and then restored in the last nine years.

The threat of fossil fuel extraction and mining remain issues. The outing was intended to take advantage of the current status before possible future changes.

We arrived in Salt Lake City April 17, rented cars, and drove to Moab and a motel for two nights. The next day we visited Dead Horse State Park in the morning for a short hike and then spent the afternoon in Arches National Park, where we hiked to Delicate Arch, one of its most famous sights.

On April 19, we drove south to the small town of Bluff, spending three nights at the Bluff Garden Cabins. Bluff is near the southern end of Bears Ears, and is a significant site in the Mormon expansion beyond Salt Lake City. There are interesting historic displays (including multimedia presentations) at Fort Bluff. After settling in the cabins, we headed up nearby Lower Butler Wash to hike into Wolfman Panel, a petroglyph site with some ruins. The hike required a bit of scrambling to reach the bottom of the canyon floor where it is located.

The next day, April 20, we further explored Lower Butler Wash to see the Monarch Cave and Cold Springs Cave.

Monarch has impressive and largely intact ruins beneath a large overhang.

April 21, was mostly spent driving. First we went to Goosenecks State Park, where the San Juan river provides a dramatic example of an entrenched river meander. Later, the group drove up the Moki Dugway, a backcountry road famous for its steep, unpaved, but sharp switchbacks, which ascend 1,200 feet to the top of Cedar Mesa. Following a return down the Dugway, we drove through the Valley of the Gods, with towering rock formations and open desert landscape. This is somewhat similar to nearby Monument Valley, but relatively uncrowded,

Our last day in Bluff, April 22, we spent the morning with a short hike into a wellknown procession panel. The impressive petroglyph, representing a ceremonial gathering or migration story, depicts 179 humanlike forms coming from three different directions and converging on a central circle. We returned to Bluff, then traveled an hour north to the larger town of Blanding. Here we spent four days in a comfortable, four bedroom condo.

On April 23, we drove west on Highway 95, then south on Cedar Mesa to reach the Moon House ruins. This hike requires

getting limited advance permits. Of all the archaeology sites on the mesa, many consider Moon House to be among the best. The well-preserved site, consisting of three separate dwellings with a total of 49 rooms, is one of the largest on the mesa. The approach road is rather slow and rough. The hike in requires more scrambling than any of the others and has a crux that is somewhat exposed class 3, which was assisted with a short hand line.

On April 24, we drove to Natural Bridges National Monument, and did the three most significant bridges: Sipapu, Kachina, and Owachomo. The hikes involved some interesting travel over slickrock with a number of ladders in spots.

April 25, we drove to the South Fork Mule canyon, 20 miles west of Blanding, just north of US-95. A mile of easy hiking reaches 700-year-old ruins, which consist of about five rooms and that are frequently referred to as the House on Fire because patterns in the alcove’s red and white sandstone ceiling look like flames shooting from the roofs of the structures. The next objective was Fish Mouth Cave. This is a very large cave-like overhang in lower Butler Wash road. This is part of Comb

Ridge, a stunning sandstone ridge of steeply tilted rock layers called a monocline.

April 26, we said goodbye to Blanding and headed north to Salt Lake City and our return to Portland.

Overall, this was a rewarding trip. Bears Ears does not have the crowds of the better-known national parks. It requires research to identify suitable hiking objectives and archaeological sites to visit. The roads and trails can be a bit rough at times and hard to follow. It is especially worthwhile for those who have the time and interest and are looking for something different.

Bob Breivogel, leader; Rex Breunsbach, assistant; Alice Brocoum; Jay Feldman; Gaoying Ren; Edward Kaiser; Pam Rigor; Leigh Schwartz.

BOB BREIVOGEL

Bob has been a Mazama member since 1982. He is a climb, trail trip, and outing leader, having lead over 300 climbs and 15 outings. He has served two terms on the Mazama Board of Directors. He is currently the Outing Committee co-chair.

Facing: Moon House Ruins, Bears Ears National Monument.

Above top: Outing members at Goosenecks State Park, Utah.

Above left: Procession Panel, Bears Ears National Monument.

Above right: Hiking in Natural Bridges National Monument

Photos: Bob Breivogel

by Mathew Brock, Director of Special Collections and Media

Welcome to “Looking Back,” an occasional column that delves into the rich history of the Mazamas. As we journey through the annals of time, we’ll revisit the remarkable events, happenings, and adventures that have shaped the organization’s legacy. From awe-inspiring mountaineering triumphs to community milestones, this column serves as a nostalgic look back at the moments that have shaped the Mazamas.

The September and October 2000 Bulletins marked a significant transition with the departure of beloved lodge managers Jasmine and Jason Star after four years of exceptional service. Their culinary skills had become legendary among members, and they were praised for maintaining solid financial footing while creating a welcoming atmosphere. Todd and Wendy Koebke were welcomed as the new managers, bringing fresh enthusiasm for continuing lodge traditions.

A major honor was bestowed when Bradford and Barbara Washburn were nominated as Honorary Members for 2000 and 2001. Brad’s extraordinary accomplishments included mapping areas of the Northeastern US, Alaska, Yukon Territory, and Grand Canyon using innovative photogrammetric techniques. Barbara was noted as the first woman to summit Denali (Mt. McKinley). Their joint nomination recognized collaborative work that advanced mountaineering and exploration.

The Explorer Post achieved a remarkable milestone during a 9-day trip to the British Columbia Coast Range, completing a first ascent of an 8,700-foot unclimbed peak. Students decided to name the peak for Vera Dafoe, recognizing her dedication to the Explorer Post through regular climbs and soliciting donations for expensive equipment.

The September and October 1950 Bulletins revealed the Mazamas involvement in wildlife conservation through the Oregon State Game Commission’s project to reintroduce mountain goats throughout Oregon’s Cascade Range. The organization took particular pride in this initiative involving their namesake animal and organizational symbol.

The Washington Department of Game permitted Oregon to trap 25 mountain goats in exchange for pronghorn antelope Oregon had previously provided to Washington State. Live-trapping experts successfully relocated six goats—three billies and three nannies—to the Wallowa Lake area. One nanny died shortly after

release, but the others showed as healthy specimens when last seen.

Mazama members were encouraged to watch for released goats during climbs of nearby Joseph Peak. The organization viewed this as both a conservation victory and symbolic heritage connection— reintroducing their namesake animal to Oregon’s high country represented a tangible contribution to wilderness preservation.

The September and October 1925 Bulletins showcased pioneering scientific work with the Mazama Research Committee’s systematic study of Eliot Glacier movement on Mt. Hood. The committee established precise measurements using iron pipes and large yellow circles painted on terminus rocks. Eight-foot stakes were placed at varying distances, with measurements taken every three weeks for nine weeks. Data revealed maximum movement of about two feet, equally distributed across periods. This groundbreaking research was planned to continue for years, providing valuable Pacific Northwest glacial behavior data.

Jack Harvey achieved a remarkable mountaineering feat by setting a new Mt. Rainier speed record. The Seattle PostIntelligencer reported Harvey broke the existing record, climbing from Camp Muir to summit in three hours, then returning in two hours and fifteen minutes creating dual records that demonstrated exceptional Mazama climbing standards.

Betty London’s “A Mazama in Norway” provided fascinating international glacial exploration accounts. Writing from aboard the S.S. Araguaya, London described Norwegian glaciers that “spurred themselves carelessly over mountain tops,” rising 6,000 feet from deep fjord waters. She observed unique local techniques for glacier travel, providing comparative knowledge that enriched the Mazamas understanding of international climbing conditions.

Above: Mazama Research Committee member on Eliot Glacier, September 15, 1935.

Photo: Mazama Library & Historical Collections

by Mathew Brock, Mazama Bulletin Editor, Darrin Gunkle, Publications Committee Chair, and

Kate Evans, Conservation Committee representative.

Welcome to the conservation issue of the Mazama Bulletin. As climbers and outdoor enthusiasts, we’ve witnessed firsthand the dramatic changes affecting the landscapes we love—from retreating glaciers on our beloved peaks to the increasing frequency of wildfire closures that alter our access to wilderness areas. This issue confronts these challenges head-on while celebrating the remarkable conservation efforts taking place across the Pacific Northwest.

This issue arrives during a significant transition for our organization. We’re honored to introduce Interim Executive Director Jill Orr, who joined the Mazamas in August following Rebekah Phillips’ departure. Jill brings more than two decades of nonprofit experience and a deep personal connection to the outdoors— from her childhood exploring Iowa’s trails to recent adventures backpacking in the Rockies. Her priorities during this transition include listening and learning from our community, supporting our incredible staff, strengthening communication, and laying groundwork for our next permanent Executive Director. As she writes in her message to members, “The outdoors doesn’t take care of itself— we have a part to play in keeping it healthy and worth coming back to.”

The Mazama Board of Directors echoes this sentiment in their report, reminding us that “what we love, we protect.” With federal agencies facing resource cuts and environmental safeguards under threat, the board emphasizes that our advocacy and stewardship work is more crucial than ever. As they search for our next Executive

Director through a board- and memberbased hiring committee, they continue to be guided by our 2025-2027 Route Ahead strategic plan, focusing on priorities that create a more substantial and impactful future.

Our feature articles tackle some of the most pressing conservation issues of our time. Sharon Selvaggio provides a sobering analysis of how the U.S. Forest Service, under current policies, is elevating logging as its sole priority at the expense of the multiple-use mandate that has guided our National Forests for decades. Suzanne Cable follows with a case study from the Enchantments, examining how staffing cuts and policy changes are creating an environmental crisis in one of our most cherished alpine destinations.

From there, we shift to the human stories within conservation. Luke Davis profiles Mazama member Luke Espinoza’s journey from insurance work to woodland firefighting, offering an intimate look at those on the front lines of protecting our forests. Joe Riedl interviews Dr. Paul Loikith of Portland State University about Oregon’s climate future, providing the scientific context for the changes we’re seeing in our mountains.

The issue celebrates conservation successes as well. The North Coast Land Conservancy staff details how community collaboration created Oregon’s Rainforest Reserve, while Tom Bode examines 25 years of wolf recovery in Oregon—a complex story of both progress and ongoing challenges.

We dive deeper into the science with the Oregon Glaciers Institute team explaining how their new GlacierTracker app (still in development) will turn summit photos into citizen science, and Brenda McComb’s detailed analysis of proposed changes to the Endangered Species Act that could fundamentally alter habitat protection.

Conservation isn’t just about policy and science—it’s about building community connections to the land. Barry Buchanan explores how conservation land trusts create bridges between communities and conservation efforts, while Darrin Gunkel interviews Dr. Thomas Doherty about his

new book on climate anxiety, offering tools for processing environmental grief while maintaining hope and engagement.

The issue concludes with practical inspiration. Jeff Hawkins celebrates five years of the Mazama Mountaineering Center’s carbon neutrality, demonstrating how conservation can work on an institutional level. And from our rare book collection, we feature eight foundational mountaineering texts that show how our relationship with wild places has evolved over centuries.

Throughout, you’ll find the regular features that connect our community— new members, successful climbers, upcoming Base Camp programs, and conservation book recommendations from the Mazama Library.

A special thanks to Darrin Gunkel, Publications Committee Chair, and Kate Evans, Conservation Committee representative, whose expertise and dedication were instrumental in pulling this conservation-focused issue together.

As we face an uncertain future for our public lands and wild spaces, this issue reminds us that conservation is not a spectator sport. Whether through citizen science, community involvement, or simply bearing witness to change, each of us has a role to play in protecting the mountains and landscapes that define our region and our organization.

Happy reading, and may this issue inspire your own conservation efforts!

by Sharon Selvaggio, Mazama Conservation Committee member

The last mountain you climbed involved a long approach through a forested landscape before hitting the summit rock, right? And the one before that, and the one before that? What is that forested land? Why is it there? What purpose does it serve?

Each of the Mazama Sixteen Peaks is surrounded by national forest land. These are public lands, belonging to every U.S. citizen, and managed by the U.S. Forest Service.

Our own local Gifford Pinchot National Forest, which encompasses both Mount St. Helens and Mt. Adams, was named after the first chief of the Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot, best remembered as a conservation-oriented leader who ensured cut and run forestry would not be the modus operandi of his nascent agency. He saw the interconnectedness of land, water, soil, forests, and people, including future generations, envisioning forests managed

for “the permanent good of the whole people.”

As a recreationist, you may see these forests as a network of trails and campsites. But turn on your faucet at home to draw water, likely piped straight from the rivers draining our local national forests. The sweet clean taste is what you get when rain is filtered through deep forest soils, layered for millennia with needle fall. Peer behind the sheetrock covering your walls and you’ll find two by fours—which could have easily come from trees that grew on your local national forest —holding up your roof. Go to the store and you’ll find salmon—birthed in Northwest and Alaskan rivers kept cold for millenia by glaciers and forest canopy. Walk through the forest and you may see salamanders, hear grouse, touch wildflowers, or sense countless other species who evolved in these forests long before humans arrived on the scene. More recently, scientists have realized that forests also play a role in mitigating climate change, by storing carbon in standing trees and soils.

The point is that national forests provide a treasure of interlinked benefits, or under the somewhat wooden language of the National Forest Management Act

and its implementing regulations, “multiple uses.” And under law and regulation, the Forest Service is required to balance these sometimes competing “uses”—timber, recreation, watersheds, wildlife, and more—through an interdisciplinary and public forest planning process. Even the restorative spiritual benefits for people spending time in forests are formally recognized in regulation.

Except now, one use is being mandated from the top to swamp all others. Logging. Timber production. Under new policy— which includes two executive orders issued this spring by President Trump, the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act ” (OBBBA) passed in July by Congress, and a secretarial memo issued by Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, who oversees national forest lands, the Forest Service is now set to massively increase logging.

The OBBBA mandates that in the years 2026–2034, the Forest Service must exceed each previous year’s total timber harvest by an additional 250 million board feet each year, which will nearly double the amount of timber hauled off national forests by 2034. If it all came from the Pacific Northwest (and we can expect that a lot of it will) an estimated 6,000 acres per

year would be clearcut just to meet the mandated annual increase.

Sadly, such mandates violate and undermine not only the Forest Plans currently governing each national forest, but also the principle of sustained yield written into national forest law since 1960. But it doesn’t matter. Through the executive orders (EOs) and secretarial memo, the administration has declared an “emergency” for national forest lands, citing threats ranging from national security to wildfire risk to forest health.

By declaring an “emergency” the administration has created a justification for short circuiting normal environmental reviews; forcing fast-tracked endangered species evaluations; and curtailing public involvement. Just to be on the safe side, the EOs also direct the Secretary to repeal any regulations that create an “undue burden” on logging.

While the so-called national security threat has been widely panned as a pretext, national forests do face threats from wildfire, drought, insects, and diseases. These are serious threats that need to be handled by serious, farsighted leaders. But rather than take a thoughtful approach to the real issues facing national forests by utilizing scientific expertise and collaborative public involvement, this

administration and Congress are pursuing logging above all else.

Shortly after the EOs were signed, Secretary Rollins made good on the order to repeal any regulation posing an undue burden to logging. She announced her intent to rescind the 2001 “Roadless Rule,” that protects nearly 60 million acres of roadless Forest Service land across the country from roadbuilding and timber harvest. Again, mitigating wildfire risk was the purported rationale. But evidence shows that roaded areas experience more fire ignitions (fire starts) than roadless areas.

The Tongass and Chugach National Forests in southeast Alaska are at special risk if the Roadless Rule is abandoned. Their roadless areas, home to 800 year old Sitka spruce, cedar, and hemlock trees, feed rivers that supply 48 million salmon annually to the commercial fishing industry. Their roadless watersheds contain thousands of miles of clean, cold rivers full of the aquatic invertebrates salmon require.

Oregon State University’s Climate Impacts Resource Consortium finds that rising temperatures due to human-caused climate change are a significant factor in the increase of wildfire in recent decades,

continued on page p. 45

The outcome is uncertain. With reduced public input and gutted Forest Service staff, logging operations may happen with little notice.

WHAT

■ Stay Alert While hiking, watch for new logging or roads. If you spot activity, call the Forest Service supervisor and ask: Why is this being logged? What environmental review was done? How does this prevent wildfires? Consider alerting the National Association of Forest Service Retirees.

■ Show Up Join my postcard and oped writing party at Lucky Lab on SE Hawthorne, Monday September 15 at 7 p.m. (back tables).

■ Use Your Network Know influential people? Whether it’s business leaders, mayors, or brewery executives (who need clean water), ask them to speak up too.

■ Support Conservation Groups Back organizations like Oregon Wild and Bark that fight for our National Forests.

Facing: AI image of logging impacts.

Image: Adobe Firefly

Above: Map of National Forests in the United States.

Image: U.S. Government Printing Office.

by Suzanne Cable

The U.S. Forest Service is headed for obsolescence. Due to recent personnel reductions, proposed budget cuts, and reorganization plans, the ability of the Forest Service to meet its legislatively mandated multiple-use mission to the American public is being systematically dismantled.

I, and many Americans, welcome thoughtful strategic reform of federal agencies, but what we have seen occur over the last several months to the Forest Service is nothing like that. We’ve seen an agency systematically and deliberately dismantled by indiscriminate firings, forced retirements, and coerced resignations. And the chaos is not over, with a drastic structural reorganization planned and looming in the future.

The large number of personnel leaving the federal government has been widely reported in the news media. What has not been daylighted, however, and specifically in the case of the Forest Service, is that since firefighter and law enforcement

positions were not eligible for the various incentives offered to encourage employees to leave, nearly all the employee reductions have come from the far-lessthan fifty percent of the remaining agency workforce. That includes personnel that serve as wilderness managers, recreation specialists, fisheries and wildlife biologists, botanists, archeologists, research scientists, and the many varieties of forestry technicians doing work on the ground.

The short-term impact of personnel reductions is being seen this summer, as all remaining employees and resources are devoted to responding to wildland fire now that we have reached national preparedness Level 3, as directed by a joint memo released by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Rollins and U.S. Department of Interior Secretary Burgum1. This is after thousands of qualified callas-needed firefighters and fire operations support personnel have lost their jobs. This will come at the expense of the many other

1 www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/pressreleases/2025/05/20/secretary-rollins-andsecretary-burgum-sign-joint-fire-memoahead-peak-fire-season-receive-fire; www. fs.usda.gov/inside-fs/leadership/updateinterim-operational-planning

mission-critical responsibilities of those remaining employees.

We’re also seeing the impact now that recreational access, information and education, law enforcement, and infrastructure maintenance is reduced or absent, even as summer public visitation to our National Forests is surging. Not unlike 2020, in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, agency personnel are again directed by their leadership to keep open all recreational access and facilities regardless of whether they can safely and responsibly operate those sites and facilities to established standards. Instead, we are seeing unmitigated damage to nature from unchecked visitation to sensitive landscapes due to unmanaged recreation. We’re seeing impacts to water quality, wildlife, and vegetation that in the most fragile and heavily used areas will never recover.

A local and especially acute example in the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest is in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. The cherished Enchantments area of the Alpine Lakes is one of the busiest wild land destinations in Washington state for Above: Goats in the Enchantments, 2022. Facing: The author at Asgaard Pass in the Enchantments, 2022.

Photos: Anonymous.

outdoor recreation, with up to 100,000 people hiking there each year in the short summer and fall season. There are usually ten to twelve wilderness rangers on rotational patrols that care for the Enchantments each summer. Due to staffing reductions, the Wenatchee River Ranger District has one wilderness ranger on duty this summer to patrol not only the Enchantments but the other 150,000plus acres of designated Wilderness in the district. Additionally, the district now has one trail crew leader and no trail crew. Usually, the District has two or three full crews not only doing their own work to maintain trails but also working with and supporting volunteers, youth crews, and professional partner crews to accomplish trail maintenance.

This situation has caused irreparable damage to wilderness character and natural resources as well as unsafe and unsanitary conditions for visitors, including unmitigated human waste and trash, parking congestion, and blocked access for emergency vehicles and search and rescue operations. As described in a recent letter to Secretary Rollins and Chief of the Forest Service Tom Schultz by Washington Congressional Representatives Kim Schrier and Adam Smith, the crisis is currently unfolding as the Forest Service does nothing to mitigate the damage2. Unlike the impacts to public lands due to visitation during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, this is an entirely self-inflicted crisis by the current administration due to implementing a poorly planned and executed deliberately destructive takedown of the ability of the Forest Service to deliver services to the American public.

The gutting of the Forest Service is just one example of a national crisis that will take years or decades to recover from once we, as a society, choose to stop the damage to our federal system of governance. We must individually and collectively speak out to all our elected officials and demand a stop to the out-of-control damage being done. We need to begin to rebuild a federal government that we can rely on to deliver critical services to the American public, including re-creating a functional Forest Service, and protecting our wild landscapes from destruction.

2 www.schrier.house.gov/media/pressreleases/congresswoman-schrierdemands-reinstating-critical-staffingaddress-dire

Suzanne Cable retired in January 2024 after a 30-year career with the U. S. Forest Service. She finished her career as the forest-wide program manager for Recreation, Trails, and Wilderness

on the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. Suzanne continues her advocacy for wilderness stewardship in central Washington and nationally.

by Luke Davis

We’ve all seen the effects of the wildfires in recent years, but none see real-time effects more than the woodland firefighters. This includes Mazama member Luke Espinoza. Espinoza, age 27, joined the Mazamas in 2023 after climbing Mt. McLoughlin. However, he hasn’t been able to use his membership for climbing yet because last year he also joined the woodland firefighters.

I’ve known Espinoza since 2016 in college and I wanted to chronicle his journey from insurance companies to woodland firefighting. It was late April 2024 when Espinoza first heard of the openings with the Oregon Department of Forestry for seasonal woodland firefighters, through a past co-worker. He didn’t have any qualifications besides Mazama activities, but the recent “radio silence” from financial and mid-level office jobs was getting frustrating. Not only that, he was looking for something more ethical than another insurance company. Espinoza saw the firefighting job as a chance to learn about and experience more environmentally related jobs in the field, as well as providing a physical challenge.

The first day on the job was June 10. Training took place mostly at Sweet Home High School, where participants pitched tents around the school for the next 5 days. During his time there, Espinoza said they were in classrooms and field sessions from 8 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. They learned all about the tools and processes with the trucks, how to dig a line (a trench-like strip in the ground to act as a barrier and travel), deploy a fire shelter (a sleeping bag like structure with a metallic antiflame coating), run a pump, and several other skills. Weather, natural fuels, and atmospheric models and changes, as well as maps and navigation were also covered. They also participated in several physical

training sessions; the final test being 13 laps (3.125 miles) around the track with a weighted vest in 45 minutes. In the field, Espinoza was trained to drive both the modified pickup truck and the modified semi-truck.

When I asked Espinoza what surprised him most about the job, he listed a few things. The first was what he described as “gym strength” and “trade strength.” The type of endurance and adaptability to rugged terrain was a new type of physical challenge to him. He described everything as a bushwhack, where he had to develop “forest legs” for quick travel. They would often have to climb ridgelines up to 60 degrees to get views of the situation from above. The upper body strength to carry tools and the standard 40 pound pack was also an adjustment, even for past football players, Espinoza described. He noted that before this job, he would have been intimidated by Mazama hikes that were

described as “strenuous,” “fast-paced,” or for “experienced” participants. He said that he wouldn’t think twice about applying for those today.

The other big surprises Espinoza described were the different types of forest and their different environments. One part of his job is that he has keys to nearly every gate on every road and has seen a lot of land that most hikers/ climbers never will. One stark difference was federal and state forests versus private lands used for logging. He said that while the federal and state lands are generally biologically diverse, the private lands are often monotonous: Douglas Firs. They are “native” [Espinoza’s quotes] so loggers can plant them everywhere, but they don’t allow for any undergrowth. He described walking through lands that felt like “a giant Above: Luke Espinoza tending hotspots. Photo: Unknown.

Christmas tree farm with no life on the forest floor.” Another surprise from the forests was the temperatures. On hot days, Espinoza feared overheating. However, he said the forests were surprisingly cool, with shade, water, vegetation, and wind acting as natural coolants. He said there were some days where the cemented cities almost felt hotter than traveling through the forest.