Transform your abilities in ICS’s intensive dual-session program. Master essential skills, organize your own adventures, and open doors to Mazama leadership. Your most dramatic climbing evolution awaits!

Course Info:

Runs: August 2025 – March 2026

Applications open: July 10

Applications close: July 30

Tuition: $1,875 member / $2,150 nonmember

Join our 3-day adventure circumnavigating Mt. Hood this Labor Day weekend! Hike through alpine meadows and glacial terrain with stunning Cascade views. Daily hikes: 13-15 miles with 2,000+ feet elevation gain. Shuttle service provided to trailheads. Evenings at rustic Mazama Lodge. Led by experienced Mazama leaders.

Round the Mountain Info:

Dates: August 29 – September 1, 2025

Applications open: Now

Applications close: June 30

Cost: $800 member / $950 nonmember

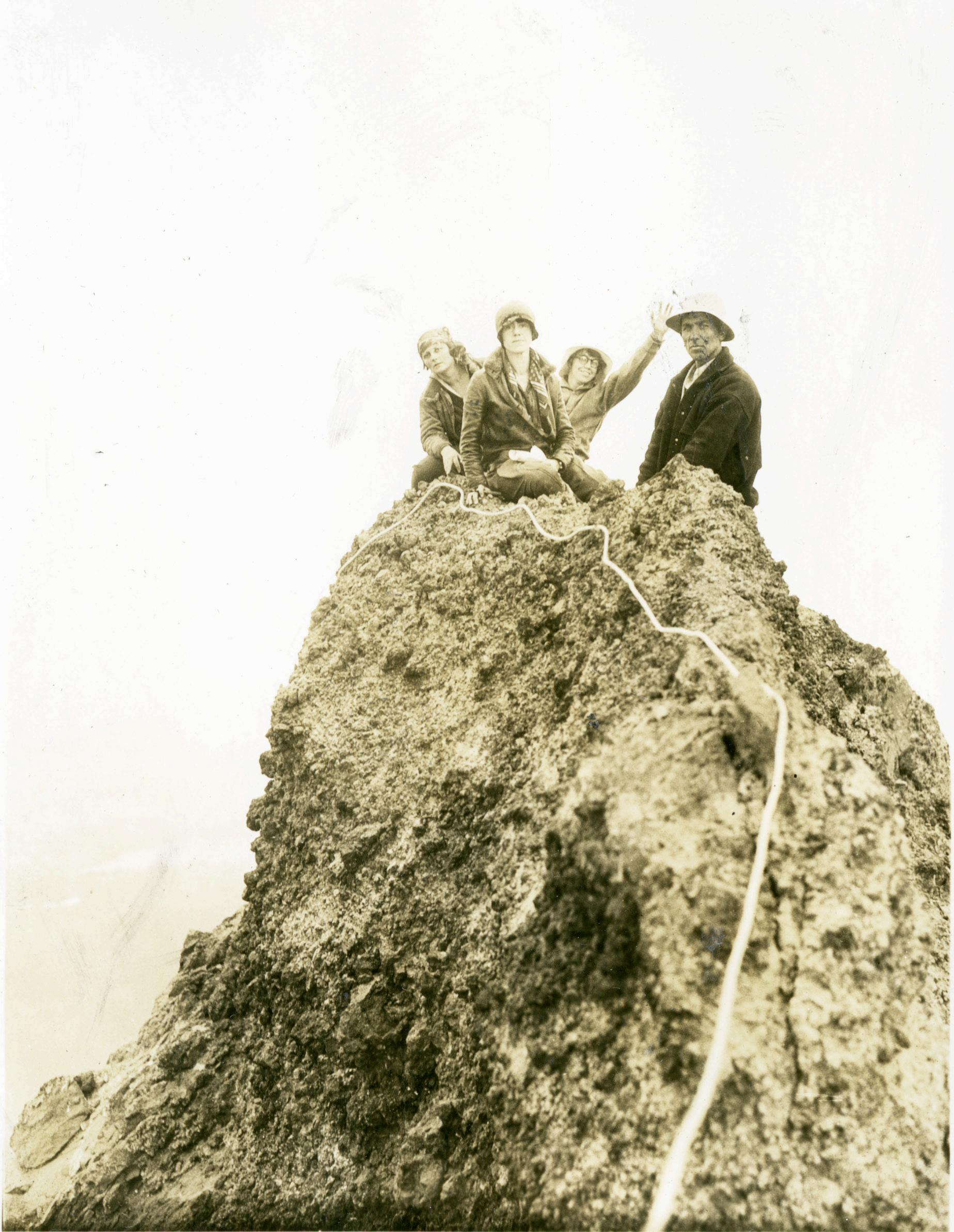

Multigenerational Mazamas, p. 14

The 16, the 7, & the 3: The Past, Present, and Future of Mazama Climbing Awards, p. 16

We Were Here, p. 24

She Climbs High! p. 28

Wheeler Peak, p. 31

Standing on the Precipice of Insanity ... and a New Era in Climbing, p. 32

Climbing Into a Community, p. 36

Looking Beyond Hood: Some of my favorite climbs, p. 38

Bikepacking on the Deschutes River Trail, p. 39

SEWS By Southwest, p. 40

Executive Director’s Message, p. 4

President’s Message, p. 5

Navigating Rising Insurance Costs, p. 5

Federal Cutbacks, Backcountry Impacts, p. 6

New Members, p. 8

Letter from the Editors, p. 9

Successful Climbers, p. 9

Upcoming Courses, Activities & Events, p. 10

Mazama Supporters, p. 12

Looking Back, p. 43

Book Review, p. 44

Board of Directors Minutes, p. 46

These actions continue against a backdrop of shifting tactics, court orders and counter-orders, and temporary backtracking.”

p. 6

A lot of ambitious Mazamas set out to climb as many of these as quickly as possible.”

p. 16

In all, the Mazamas placed and managed a total of 35 summit register boxes on peaks across the Pacific Northwest ...” p. 24

Whether you like hiking and scrambling, cragging, multipitch climbs, or big-wall style routes, there’s something for everyone here.”

p. 40

Volume 107

Number 3

May/June 2025

by Rebekah Phillips, Mazama Executive Director

Welcome to summer!

While many of you are likely out on your own epic hiking, climbing, and backpacking adventures, here at the Mazamas we’re facing our own kind of mountain. Steep terrain, rocky slopes, tough conditions, and no clear beta for what’s ahead. But we’re not just trudging along in the dark. We’re drawing on the strength of our legacy and the power of our community to reach our destination together.

There’s no doubt that the current political climate in the United States is posing significant challenges for nonprofit organizations, including our own. Like for-profit businesses, nonprofits require sound financial management, strategic planning, and adaptability. However, unlike for-profit entities, we rely on the generosity of donors, alongside program revenue, membership dues, and volunteers, to sustain our operations. At the Mazamas, this interdependence between our revenue streams and the community we serve makes the economic uncertainty we face especially acute. When our members experience a reduction in income, reduced spending power, or limitations on free time, we too feel the effects.

The Mazamas is not alone in confronting these challenges. Many organizations, both nonprofit and for-profit, are experiencing hardship, particularly within the environmental sector. Recent rollbacks on global climate commitments, alongside policy reversals and the elimination of wilderness protections, have left key partners struggling to respond. It is early April as I write this; just last week, after firing thousands of USFS employees, the current administration took steps to open nearly 60 percent of our national forests and federal lands to logging. The state of

emergency declared over domestic timber supply and forest health directs agencies to eliminate environmental reviews (and therefore science-based decision making) and accelerate logging across the Pacific Northwest. Adjacent cuts to NOAA and the potential gutting of the Columbia River Gorge Commission—the agency that safeguards the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area—also pose serious threats to our ability to carry out our mission. It’s difficult to predict what further, potentially irreversible, damage will have been done by the time this Bulletin hits mailboxes in May.

Nevertheless, one of the defining qualities of nonprofits is our capacity for resilience and innovation in the face of adversity. Unlike for-profit businesses that often prioritize profit over purpose, we are uniquely positioned to tackle problems that others have deemed unprofitable. The Mazamas excels in community building, mountaineering education, and safety. Our programs provide a network, knowledge, and skills that cultivate strength, resilience, and determination—interconnected qualities that empower us to overcome both internal and external challenges.

The impact of the Mazamas is extraordinary: we drive both social change and personal growth, and this is a cause for celebration. Much of the credit for this is due to our dedicated program and activity leaders, whose tireless efforts in organizing, planning, and mentoring help transform today’s participants into tomorrow’s committee chairs, climb leaders, and board members, advocating on behalf of the Mazamas and serving as ambassadors of our mission wherever they go.

There are countless ways to support the causes that matter most to you, whether they are local or global, large or small. Now, more than ever, it is critical that we stand together to drive meaningful change. Some of us may choose to support a range of causes, while others may prefer to dedicate their efforts to one particular issue. Whatever your approach, by connecting with others, engaging with diverse perspectives, raising awareness, or empowering others to act, you inspire all

“The impact of the Mazamas is extraordinary: we drive both social change and personal growth, and this is a cause for celebration.”

of us to take initiative in working toward a brighter future.

If you are able to make a financial contribution, please consider supporting the Mazamas as well. As a nonprofit organization, your charitable contributions help us sustain and expand our programs, ensuring that we can continue to organize this robust community around our mission. Whether through your time, talent, or treasure, your involvement is critical to our success. Now is the time to play your part, to be hands-on with the organizations and causes you care most about.

As we navigate the challenges ahead, it is my hope that the Mazamas will continue to be a source of inspiration for all who share a passion for the outdoors, as it has been since 1894. Thank you for standing with us in the fight to preserve public lands, promote scientific research, advocate for environmental justice, and ensure that our beautiful forests and mountains remain protected for generations to come. Thank you for making the Mazamas a priority in your life. Together, we will ensure that this community remains a vital force for good. Climb on!

by Debbie Dwelle, Mazama President

It starts in the dark— headlamps cutting through cold air, boots crunching over frost-hardened trail. Packs are heavy. The summit is far. But step by step, we move forward. In alpine climbing, there’s no shortcut— only the long, deliberate journey upward.

This is the spirit we carry as the Mazamas: commitment, resilience, and a deep respect for the places that test us. Our mission as a community isn’t just to chase summits—it’s to build a community that loves and protects the mountains. Because the places that challenge us the most are also the ones that need us the most right now.

Every time we rope up or posthole into a high basin, we’re reminded of what’s at stake: vast alpine cirques, fragile ecosystems, pristine ridgelines. These wild places define who we are—not just as climbers, but as stewards.

But these lands are facing growing pressure—both close to home and across the country.

Nationally, we’re seeing renewed pushes for oil and gas development on public lands, rollbacks of environmental protections, and attempts to transfer federal lands to state control—moves that could open the door to privatization

and restricted access. Climate change is accelerating, reshaping landscapes we once thought timeless: melting glaciers, shifting weather patterns, and destabilized ecosystems.

Here in the Pacific Northwest, the threats feel especially personal. Increased wildfire frequency, driven by climate change, is already transforming the alpine zone. Old-growth forests—some of the last of their kind—face renewed logging pressure under the guise of fire mitigation. Conservation safeguards for keystone species and waterways are being challenged, while efforts to expand infrastructure and recreation in sensitive areas raise difficult questions about access and impact.

These aren’t abstract policy debates— they’re decisions that shape the future of the places we hike, climb, camp, and find solitude as well as connectedness.

That’s why our mission must go beyond climbing. As an organization, and as individuals, we’re called to protect what we love. We know what it means to work hard for a summit; we also know what it means to turn back when conditions demand it. That same judgment, endurance, and long-view thinking apply to stewardship. The route ahead may be complex, but the objective remains clear: preserve wild places for the generations of climbers who will come after us.

We’re not alone on this rope team.

Through trail work, education, public advocacy, and local action, we’re building

a movement rooted in shared values. Our strength lies in community—people who show up, who speak up, and who hold the line when the terrain gets steep.

Whether it’s writing to a representative, volunteering on a trail crew, or introducing someone new to the alpine world with Leave-No-Trace values in hand, every act matters. The mountains have shaped us— now it’s our turn to return the favor.

Because in the end, alpine climbing isn’t just about standing on top. It’s about the way we get there. It’s about the team, the ethic, the care we bring to every decision. And that’s exactly what it will take to protect the landscapes we so deeply love and call home. So let’s stay roped together—not just on the mountain, but in our mission to build a community that inspires everyone to love and protect the mountains.

by the Mazama Board of Directors

Over the past year, the Mazamas— like many outdoor nonprofits—have faced rising insurance costs at an unprecedented scale.

Despite our long history of strong safety practices, in early 2024 our general liability carrier declined to renew our policy, citing a reduced appetite for risk across the entire outdoor recreation sector.

We secured replacement coverage, but at a much higher cost. Premiums jumped to more than 17 percent of our annual operating budget—an amount that isn’t sustainable.

Since then, the staff and board have worked together to explore every option, including bids from other carriers, raising deductibles, and adjusting coverage terms. Unfortunately, the industry-wide price spikes left us little room to maneuver.

This month, the board made the difficult but necessary decision to cap insurance spending at 15 percent of

projected annual revenue. To meet this limit, we reduced some coverage limits and increased deductibles. While this does mean the Mazamas are accepting more financial risk, we have retained the core coverage to protect our members, volunteers, and operations.

We are committed to monitoring the situation closely and adjusting our risk management strategies as needed. Know that the Mazamas remain insured and fully committed to maintaining the safety standards that have always been part of who we are.

by Mazama staff

Over the past several months, the mass firings of federal workers, closures of agency offices, cancellation of grants and other funding, and abrupt changes to established policies have set the stage for impacts to many services we Mazamas have come to expect when we venture into the backcountry. In particular, the current administration has moved to slash National Parks, National Forest, and NOAA staff, open more than half of National Forests to logging, and rescind contracts for maintenance and other support work.

These actions continue against a backdrop of shifting tactics, court orders and counter-orders, and temporary backtracking. With so much uncertainty, specific impacts are impossible to determine. However, Mazama hikers, climbers, and leaders should approach trip planning with particular caution this year, not assuming routine levels of road clearance, campground and trail maintenance, and climbing-related support staff, including climbing rangers and some search and rescue (SAR) operations.

Although many employees fired in February were called back in March, all these agencies face unspecified “reductions in force” in the coming months, so eventual staffing and service levels are unknown. The Washington Trails Association (WTA) expects these new cuts to be severe, along the lines of the February firings, but phased in over time.

Currently, the National Parks appear to be in the best shape. As of this writing, Rainier National Park believes climbing rangers, who are seasonal workers, will be hired and working this year. After several months of confusion, Climbing magazine reports that Yosemite National Park has restored funding for most services,

although its SAR efforts will be staffed only by employees; the many climbers who supplement Yosemite SAR, and perform many of the rescues of climbers and tourists alike, will apparently not be hired this year.

National Forest staffs were decimated by firings and buyout offers in February, then partially restored by court order and agency backtracking, but face further actions beginning in late April. In February, the Okanogan–Wenatchee National Forest, which includes the Enchantments, Alpine Lakes, Glacier Peak, Chelan, Pasayten and other wilderness areas, lost 40 employees, including 10 of the 13 staff managing recreation in the Enchantments and adjacent areas; the agency was already bare-bones after funding restrictions put in place last year. According to the WTA, 70 percent of the Mt. Baker–Snoqualmie National Forest’s recreation staff were fired in February, leaving 16 employees to manage 280 sites and 1500 miles of trail. Oregon national forest staff reductions were likely similar, although numbers are hard to find.

Support organizations such as WTA and Trailkeepers of Oregon (TKO) have been hard-hit by funding cutbacks, including the withholding of funds previously awarded. In March, TKO (which maintains OregonHikers.org) reported that “nearly $500,000 in federal funding awarded to TKO is stalled, delayed, or in question.” The cuts jeopardize their maintenance of several National Forest visitor centers, wildfire restoration work in Mt. Hood National Forest, training and certification for sawyers who clear downed trees on many trails, including the Pacific Crest Trail, support for 3,000 volunteers working on maintaining and restoring trails, and other projects.

Although most Mazama activities occur on federal lands, be mindful that state and local entities, and their contractors, are likely to be impacted by grant and other funding cutoffs as well as state and local budget shortfalls.

We recommend that those planning trips consult multiple sources to verify access and services:

■ Check recent online trip reports: WTA, Mountaineers, Cascade Climbers, Mountain Project, OregonHikers.org, Instagram, Facebook, etc.

■ Check National Forest and National Park sites for road and trail status; phone calls often work better than website postings.

■ Consult ODOT and WSDOT on road closures

In addition to more thorough trip planning, Mazamas should take time this year to do our part to help others:

■ If you observe maintenance neglect at trailheads and campgrounds, do what you reasonably can to help.

■ Write and publish trip reports, especially if you observe something unexpected.

■ Volunteer with organizations involved in trail maintenance, including the Mazamas!

This year, 2025, promises to be a fine year for hiking and climbing, but please be our eyes and ears in the backcountry this year as we work to monitor and report on federal actions and their impacts.

Mazama Mountaineering Center 527 SE 43rd Ave., Portland, OR, 97215

Phone: 503-227-2345

Email: help@mazamas.org

Hours: Tuesday–Thursday, 10:30 a.m.–4 p.m.

Mazama Lodge

30500 West Leg Rd., Government Camp, OR 97028

Hours: Closed

Editor: Mathew Brock, Bulletin Editor (mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org)

Members: Darrin Gunkel, chair; Patti Beardsley, Peter Boag, David Bumpers, Theo Cantalupo, Aimee Frazier, Ali Gray, Brian Hague, Owen Lazur, Ryan Reed, Michele Scherer Barnett, Jen Travers. (publications@mazamas.org)

MATHEW BROCK

Director of Special Collections and Media Mazama Bulletin Editor mathew@mazamas.org

RICK CRAYCRAFT Building Manager facilities@mazamas.org

REBEKAH PHILLIPS Executive Director rebekahphillips@mazamas.org

for the love of the mountains

Learn more about how you can integrate charitable giving to support the Mazamas.

Whether you’re considering a bequest in your will, setting up a charitable remainder trust, or exploring other options, by including a planned gift in your legacy, you’ll secure our continued success while ensuring that your passion endures for generations to come.

If you’ve already decided to include the Mazamas in your estate plans, we invite you to let us know. You’ll want to be sure that you’ve recorded the Mazamas with the Tax ID (EIN) 93-0408077.

Even ordinary people can make an extraordinary difference.

CONTACT US: Lena Toney, Development Director 971-420-2505 | lenatoney@mazamas.org

BRENDAN SCANLAN Operations & IT Manager brendanscanlan@mazamas.org

LENA TONEY Development Director lenatoney@mazamas.org

CATHY WILDE Finance & Administration Manager cathywilde@mazamas.org

For additional contact information, including committees and board email addresses, go to mazamas.org/contactinformation.

MAZAMA (USPS 334-780): Advertising: mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org. Subscription: $15 per year. Bulletin material must be emailed to mazama.bulletin@mazamas.org.

The Mazama Bulletin is currently published bi-monthly by the Mazamas—527 SE 43rd Ave., Portland, OR 97215. Periodicals postage paid at Portland, OR. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to MAZAMAS, 527 SE 43rd Ave., Portland, OR 97215. The Mazamas is a 501(c)(3) Oregon nonprofit corporation organized on the summit of Mt. Hood in 1894. The Mazamas is an equal opportunity provider.

Ready to Level Up Your Steep Snow and Ice Climbing?

Are you an ICS graduate—or a climber with similar experience—looking to build your confidence and skills on steeper snow and alpine ice terrain? The Mazama Steep Snow & Ice Skill-builder (SSI) might be the perfect next step for you!

Virtual Information Night:

■ Wednesday, May 28, 2025

■ 6:30–7:30 p.m.

■ Zoom link available on Mazama Calendar

Course Highlights:

SSI is designed to help climbers refine their movement and decision-making in steeper, more complex terrain. You'll focus on confidently using your ice axe and crampons as your main tools for both security and upward progress— whether you're front-pointing up firmer slopes or moving with more traditional techniques on snow.

While this course does not include leading on ice, you will get hands-on experience placing ice screws and climbing short sections of alpine ice— excellent prep for objectives like the Reid Glacier Headwall. Throughout the course, we’ll emphasize risk management and sound judgment in every scenario.

Application Dates:

■ June 1–21, 2025

■ Applicants will be notified of their status by July 4, 2025.

Course Format:

The course runs in August 2025 and includes three weekday evenings at the Mazama Mountaineering Center (MMC) and one weekend field session on Mount Hood. The class will be divided into Team A and Team B to allow for more participants.

All students must attend the first two MMC evenings:

■ MMC Session 1: Tuesday, August 5

■ MMC Session 2: Thursday, August 7

Team A:

■ Foam Ice Wall Practice: Tuesday, August 12

■ Mt. Hood Field Session: August 16–17

Team B:

■ Foam Ice Wall Practice: Tuesday, August 19

■ Mt. Hood Field Session: August 23–24

Please also reserve September 6–7 as a weather contingency weekend.

This is an incredible opportunity to build the skills and confidence needed to take on more challenging alpine routes. We hope to see you at the info night!

Between February 1, 2024, and March 31, 2025, the Mazamas welcomed 91 new members. Please join us in welcoming them to our community!

Dorothee Abbott

Wenzel Abels

Eddie Allen

Lynne Backman

Austin Bauman

Sylvie Bobo

Alex Breiding

Matt Brown

Nancy Brown

Jordan Burgess

Kimberley Byelick

Pilar Calderin

Dale Carstensen

Terra Cathey

Ben Clark

Nolan Conley

Austin Cooper

Dylan Corbin

Brandon D’Andrea

Giang Dang

Trina Delany

Kim DeMent

Sarra Devalence

Sylvie Donovan

Nicole Durchanek

Joshua Ewing

Joe Faski

Noah Flick

Tom Frisch

Ian Fuller

Kiran Hall

Scott Hamlin

Laura Harmon

Michael Hermanny

Zach Hogue

Zachary Horton

Dan Hoyt

Nick Jurgensen

David Klingman

Diana Knopik

Art Koehler

Alyssa Koida

Lori Lancaster

Austin Lee

Lewis Lem

Amber Little

Kimberly LoganElwell

Monty Lunsford

Juliana MacFarlane

Jana MacNally

Alexander Madej

Cheryl Marthaller

Eliot Martin

Matty McComish

Harrison Means

Gregory Mockford

Sofia Molvi

Brooklyn Noel

Molly O’Donnell

Ronan Peck

Ekena Pinage

Laurynas Rekasius

Olga Roshet

Gerald Runyan

Lexy Scarpiello

Nick Scheimann

Kegan Scowen

Rachel Sherrard

Kevin Shevel

Jeff Sillick

Sumeet Singh

Dan Slowey

Aidan Sojourner

Craig Southwell

Nick Spanier

John Spann

Carrie Stein

Lauren Stern

Shylee Stroud

Shelley Tinkham

Yana Ulitsky

Jessica Vo

Robert Vogel

Mike Ward

Andrew Weygandt

Dustin Wienecke

Johnsie Wilkinson

Jordan Williams

Patricia Winkler

Judi Canada Wolff

Jason Woodrow

by

Mathew Brock, Mazama Bulletin Editor, and Ryan Reed, Content Editor

Welcome to the alpine climbing issue of the Mazama Bulletin. Whether

you’re fresh from Basic Climbing Education Program (BCEP) or an experienced climber, we think you’ll find something of interest in this issues’ lineup of articles.

We begin with two important messages: one from Mazama Executive Director Rebekah Phillips and another from our staff, addressing the concerns about threats to outdoor recreation by the current administration in Washington, DC. This is followed by insights from Mazama President Debbie Dwelle, who delves into

Jan. 20, 2025-Mount St. Helens, Swift Creek Worm Flows (No Permit). Janelle M Klaser, Leader; James M Jula, Assistant Leader. Peter Boag, Kristen R. Frank, Alex Kunsevich, Cliffe Kim, Sergei Kunsevich.

Jan. 26, 2025-Mt. St. Helens, Swift Creek Worm Flows (No Permit). Laetitia Ma. Pascal, Leader. Margo Conner.

Feb. 28, 2025-Mt. Hood (Wy’east), South Side. Pushkar Dixit, Leader; Rob Sinnott, Assistant Leader. Bikash Padhi, Assistant Leader. Matt Snyder, Ryan Shafer, Chris Rivard.

Mar. 1, 2025-Mt. Hood (Wy’east), Wy’east. Darren Ferris, Leader; Ryan Reed, Leader; Gordon Wilde, Assistant Leader. Kaitlyn Beecroft, Gordon Wilde, Heather Nesheim, Noel Tavan.

the board’s strategic planning process and priorities.

Our feature articles start with Patti Beardsley’s heartwarming look at multigenerational Mazamas and the stories they share across decades of climbing. Ryan Reed then provides a comprehensive exploration of the history, current state, and future of the Mazama climbing awards program, traditionally focused on the 16 Peaks.

Mathew Brock takes us on a journey through the history of summit registers, while Amy Brose, Rick Craycraft, and Jeff Thomas collaborate on the first of several articles profiling early Mazama women climb leaders who broke barriers in the sport of climbing.

For those interested in specific peaks, Joan MacNeal offers a compelling profile of Nevada’s Wheeler Peak, and Peter Boag examines the first ascent of Three Fingered Jack and its aftermath. Darrin Gunkel

shares a touching narrative about finding an unexpected community during a climb of Mt. Baker, while Jen Travers highlights less well-known peaks for both new BCEP grads and those with more training, and recounts this spring’s first Mazama bikepacking trip on the Deschutes River Trail.

Rounding out our features is Brian Hague’s thrilling report on a snow-season trip up the Southwest Couloir of South Early Winters Spire in Washington’s North Cascades.

Throughout the issue, you’ll find all the regular columns you’ve come to expect: New Members, Successful Climbers, Looking Back, and a thoughtful book review by Publications Committee alumnus Brian Goldman.

We hope this issue inspires your next alpine adventure!

Altitude Training

• 10% off for all Mazamas members

• 50% off for climb leaders!

650 square ft Altitude Training room with altitudes from 10,000’ to 13,000’

Benefits of Altitude Training:

• Improved sea level or at altitude performance

• Improved aerobic fitness

• Increased strength

• Pre-acclimation to high altitude locations

• Accelerated recovery and return from injuries

• Maintenance of fitness while injured

• Increased fat metabolism

• Increased mitochondria production

• Increased energy production

• Increased capillary density

• Increased oxygen delivery

Applications open: Tuesday, May 6, 2025

Course dates: May 27–June 4, 2025

Location: Mazama Mountaineering Center

Cost: $180 members / $200 nonmember

The Mazama Advanced Rock Program (AR) presents a comprehensive fourevening-session skill-builder focused on high angle rescue techniques. Hosted at the Mazama Mountaineering Center, participants will master essential skills including ascending and descending systems, mechanical advantage, and spider rappel. Prerequisites for this course include documented experience leading at least three multipitch routes within the past year, plus a current belay certification from a local climbing gym. Students must already be sport climbing, anchor building, lead belaying, and performing multipitch techniques, as these fundamentals will not be covered. This skill-builder offers the perfect stepping stone for climbers ready to advance their skills.

Date: Thursday, May 8, 2025

Time: 6:30–8:30 p.m.

Location: Mazama Mountaineering Center

Cost: Free

Environmental activist Rand Schenck will discuss his book Forest Under Siege: The Story of Old Growth After Gifford Pinchot. He will examine 100 years of Pacific Northwest forestry, through the lens of forestry practices in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. This volume offers his visceral perspective on decades of stewardship, relentless harvest, and the move toward the rebirth of old growth. Rand has worked for the Sierra Club and the Oregon Natural Resources Defense Council (now Oregon Wild), and helped found 350PDX and Mobilizing Climate Action Together (MCAT), which works to implement climate-smart forestry.

Date: Wednesday, May 21, 2025

Time: 6:30–8:30 p.m.

Location: Mazama Mountaineering Center

Cost: Free

Enjoy a screening of The Volunteers - Mountain Rescue Brings Us Home, a documentary by Mark S. Weiner. Two mountain rescue organizations—one near Seattle, Washington, the other in Tyrol, Austria—are linked by a surprising historic connection. Historian Mark Weiner takes us on a journey from America to Austria as he considers the origins and meaning of their work. Both groups have grown from a strong sense of place—because before you can save a stranger, you first must love your home. Q&A to follow with co-producer/codirector David Ritsher and Portland-based cinematographer Sean Conley.

Date: Thursday, May 15, 2025

Time: 6:30–9 p.m.

Location: Steeplejack, 2400 NE Broadway, Portland, OR 97232

Join us for a casual get-together for Mazama Climb Leaders & Leadership Development Candidates to socialize, share insights, and learn about routes in the Pacific Northwest! Connect with fellow climb leaders, exchange beta on routes, and hear about upcoming climbs for the season. The evening will include a 30-minute presentation about Sloan Peak—get the inside scoop on this gorgeous PNW climb!

Details:

■ 30-minute presentation about Sloan Peak beta by Tim Scott—don’t miss it!

■ This evening will also be a great chance to chat with other climb leaders about beta and the climbs they have planned for the upcoming season.

■ Food & Drink: Will be available for purchase (not covered by the Mazamas).

Come for the beta, stay for the conversation —we hope to see you there!

Dates: August 5–20, with field sessions

August 16–17 and August 23–24, 2025

Info night: May 28, 2025 (Zoom)

Application dates: June 1–21

Notification of acceptance: July 4

More info: www.mazamas.org/ssi

Are you interested in climbs like Mt. Hood’s Reid Headwall, the Adams Glacier, and the Kautz route on Mt. Rainier? The Steep Snow & Ice skill-builder is designed for early intermediate alpine climbers who want to start building the skills necessary to tackle routes like these. SSI occurs in August and features several evening sessions at the Mazama Mountaineering Center to discuss the unique risks and hazards of winter climbing. This is followed by a weekend field session putting our new techniques into practice on steep snow and icy seracs on Mt. Hood’s Elliott Glacier. Students will multi-pitch climb ice slopes, practice building anchors and rappelling, and mock lead on the steeper stuff.

Prerequisites are graduating from ICS or having similar climbing experience, as well as having done some post-ICS climbing on snow and ice.

Dates: August 29–September 1, 2025

Applications open: Now

Applications close: June 30, 2025

Cost: $800 members / $950 nonmember More info: www.mazamas.org/rtm

Round the Mountain is back this Labor Day, August 29–September 1, 2025. Join us as we set out from the Mazama Lodge each day for a 13 to 14-mile adventure. We carry only day packs, because each night we return to the lodge for great food, hot showers, a cozy bunk, and stories from your day on the trail. Your adventure includes all meals and dorm lodging. Shuttle vans will transport you from our meeting place in Portland to the Mazama Lodge, as well as to/from the trailhead each day.

Date: Friday, October 3, 2025

Location: Mazama Mountaineering Center

Cost: $995 members / $1,350 nonmembers

Applications period: July 18 – August 18

The Wilderness First Responder course combines 30 hours of online learning over five weeks with 45 hours of hands-on training across two weekends. Weekend #1 takes place at the Mazama Mountaineering Center, while Weekend #2 includes an overnight stay at Mazama Lodge on Mt. Hood with meals provided. CPR training and certification included in course price.

Have you considered becoming a Stop the Bleed (STB) Instructor? The Mazama First Aid Committee is looking to expand our first aid skill-builder mini-course offerings. The Mazamas recently applied to become a national STB education center and are applying for a STB instructional material grant. Having more STB instructors and more classes helps with our application and provides a community benefit. Goto www.bit.ly/MazFASTB and see if you are eligible to become a STB instructor. The list of eligible health care and non-health professionals includes: WFR, Ski Patrol, OSHA instructors, lifeguard, dietician, pharmacist, and law enforcement to name a few.

If you check your eligibility and committed to becoming a STB instructor, send an email to firstaid@mazamas.org. Thank you for considering becoming a part of the Mazama First Aid community!

Help us reduce our environmental footprint by opting out of receiving the printed Mazama Bulletin. By choosing the digital-only version, you'll:

■ Save trees and reduce paper waste

■ Decrease carbon emissions from printing and shipping

■ Access the same great content instantly on any device

■ Support our commitment to responsible environmental stewardship

The digital Bulletin offers enhanced features like searchable text, clickable links, and high-resolution photos while helping preserve the natural spaces we all cherish.

Ready to make the switch?

Simply visit tinyurl.com/ MazBulletinOptOut. Thank you for helping us protect the environment we love to explore.

We envision a vibrant, inclusive community united by a shared love for the mountains, advocating passionately for their exploration and preservation.

We value every member of our community and foster an open, respectful, and welcoming environment where camaraderie and fun thrive.

We prioritize physical and psychological safety through training, risk management, and sound judgment in all activities.

We promote learning, skillbuilding, and knowledgesharing to deepen understanding and enjoyment of mountain environments.

We celebrate teamwork and volunteerism, working together to serve our community with expertise and generosity.

We champion advocacy and stewardship to protect the mountains and preserve our organization’s legacy.

Building a community that inspires everyone to love and protect the mountains.

We gratefully acknowledge contributions received from the following generous friends between April 1, 2024 – March 15, 2025. If we have inadvertently omitted your name or listed it incorrectly, please notify Lena Toney, Development Director, at 971-420-2505.

Anonymous (23)

David W Aaroe & Heidi A Berkman

Patricia Akers

Stacy Allison

Wanda M Amodeo

Jerry O Andersen

Dennis H Anderson

Edward L Anderson

Peggy B Anderson

Justin Andrews

Carol M Armatis

Jerry Arnold

Kamilla Aslami

Chuck Aude

Gary R Ballou

Tom Bard

Dave Barlow

Jerry E Barnes

Michele Scherer Barnett

John E Bauer

Scott R Bauska

Tyler V Bax

Larry Beck

Steven Benson

Daven Glenn Berg

Erwin Bergman

Bonnie L Berneck

Bert Berney

Joesph Bevier

Rachel Bieber

Ken and Nancy Biehler

James F Bily

Pam J. Bishop

Gary Bishop

Bruce H Blank

Peter Boag

Andrew Bodien

Barbara Bond

Jeffrey F Boskind

Brookes Boswell

Steve Boyer

Bob Breivogel

Rex L Breunsbach

Scott P. Britell

Alice V Brocoum

Richard F Bronder

Amy Brose

Jann O Brown

Barry Buchanan

Carson Bull

Eric Burbano

Joel Burslem

Neil Cadsawan

Keith Campbell

Patty F Campbell

Anne Marie Caplan

Jeanette E. Caples

Kenneth S Carlson

Emily Carpenter

John D Carr

Marc Carver

Susan K Cassidy

Rita Charlesworth

Nancy Church

Catherine Ciarlo

William F Cloran

Kathleen Cochran

Jeff Coffin

Justin (JC) Colquhoun

Charles Combs

Kristy J Comstock

Toby Contreras

Elisabeth Cooper

Patti Core Beardsley

Doug Couch

Lori Coyner

Darrel M Craft

Adam Cramer

Rick Craycraft

Mark Creevey

Cynthia Cristofani

Tom F Crowder

Liz A. Crowe

George Edward Cummings

Jon M Daby

Julie Dalrymple

Ellen Damaschino

Gail Dana-Sheckley

Betty L Davenport

Larry R. Davidson

Tom E Davidson

Lee Davis

Howie Davis

Chris Dearth

Edward Decker

Alexander Dedman

Richard G Denman

D. Keith Dickson

Sue B Dimin

MaLi Dong

Mark Downing

Robyn Drakeford Wonser

Keith S Dubanevich

Debbie G. Dwelle & Kirk

Newgard

Michael G Earp

Richard R Eaton

Heather Eberhardt

John Egan

Rich Eichen

Toni Eigner

Donna Ellenz

Roland Emetaz

Becky Engel

Mary L Engert

Stephen R Enloe

Bud Erland

Kate Sinnitt Evans

Shelley Everhart

Mike R Faden

William F Farr

Patrick Feeney

Travis Feracota

Darren Ferris

Aimee Diane Filimoehala

Jonathon Fisher

Steven Fisher

Ben Fleskes

Dyanne Foster

Mark Fowler

Joe Frank

Daisy A. Franzini

Aimee Frazier

Trudi Raz Frengle

Ardel Frick

Hans Eugene Friedrich

Brinda Ganesh

Becky Garrett

Isabelle Gass

Kevin Gentry

Paul R Gerdes

Pamela Gilmer

Lise Glancy

John Godino

Richard Goldsand

Sandy Gooch

Diana Gordon

Dave M Green

Kanjunac Gregga

Leora Gregory

Shannon Hope Grey

Tom and Wendy Guyot

Jacob Wolfgang Haag

Jeff L Hadley

Dan Hafley

Sohaib Haider

Martin Victor Hanson

José A Haro

Terrance Heath Harrelson

Duncan A Hart

Freda Sherburne & Jeff

Hawkins

Marcus Hecht

Lisa Hefel

Sojo Hendrix

Amy Hendrix

Marshall Hill-Tanquist

Frank Hoffman

Gregg A Hoffman

Rick Hoffman

Sue Holcomb

Lehman Holder

Mike Holman

Kris Holmes

Patty H Holt

Steven Hooker

Michael Hortsch

Charles R Houston

Hal E Howard

Nathan Howell

John A Hubbard

Flora Huber

Chip Hudson

Valoree Hummel

Michael Hynes

Irene M James-Shultz

Chris Jaworski

Scott Jaworski

Joanne Jene

Brita Johnson

Megan Johnson-Foster

Greg J. Jones

Mark Jones

Thomas Jones

Julia Jordan

George Alan Keepers

Joe Kellar

Shawn Kenner

Charles R Kirk

Sergey Kiselev

Ray Klitzke

Dana S. Knickerbocker

Susan E Koch

Craig Koon

Arjun Kramadhati Gopi

Chris Kruell

Dennis V Kuhnle

Lori S LaDuke

Richard A LaDuke

Lori A Lahlum

Brenda Jean Lamb

Carol Lane

Donald E Lange

Barbara Larrain

Nathan Laye

Thuy Le

Seth Leonard

Ernest (Buzz) R Lindahl

Jason N. Linse

Natalie Linton

Margery Linza

Jeff Litwak

Craig H Llewellyn

Robert W Lockerby

Meredith K. Long

Bill E. Lowder

Alexander L. Macdonald

Joan MacNeill

Patti Magnuson

Ted W Magnuson

Barbara Marquam

Bartholomew “Mac” Martin

Bridget A Martin

Larry G Mastin

James Mater

Donald C. Mather

Allan McAllister

Margaret McCue

Mike McGarr

Jamie K. McGilvray

Wesley McNamara

Wilma McNulty

Jeff I Menashe

George T. Mercure

Barbara A Meyer

Daniel J Mick

James (Jim) Miller

Thomas M. Miller

Keith Mischke

Gerald G Mock

Gordy James Molitor

Michael Jeffrey Mongerson

Mary Monnat

Yukiko Morishige

Kristen Mullen

Dawn Murai

Megan Nace

Stephan P. Nelsen

Rachael Nelson

David L Nelson

Leah Nelson

Veronika and Jerry Newgard

Kae Noh

Caitlin E. Norman

Patricia M Norman

Ray North

Andy A. Nuttbrock

Jennifer Oechsner

Christine Olinghouse

Kathy Olson

Michael Olson

Kim Osgood

Alexa Nickola Ovchinnikov

Brent Owens

Jooho Park

Nimesh “Nam” Patel

Thomas Pauken

Phillip Petrides

Rebekah Phillips & Lars

Campbell

William D Platt

Robert T Platt

Richard Pope

Bronson Potter

Atalanta Powell

William J. Prendergast

Morgan Prescott

Rosemary Prescott

Frances Prouse

Walker Pruett

Emily Grace Pulliam

Martine Purcell

Michael Quigley

Sarah Raab

Sandy Ramirez

Cullen Raphael

Walter Raschke

Rahul K Ravel

Stacey M. Reding

Ally Reed

Ryan Reed

Steph Reinwald

Kristina Rheaume

Anne Richardson

Judy Ringenson

Lisa F Ripps

Echo River

Andy Robbins

Reigh Robitaille

Margaret Rockwood

Jeffery V. Roderick

David Roethig

John Rowland

Steven Ruhl

Gerald Runyan

Travis Sadler

Mark R Salter

Ellen Satra

Bill Schlippert

Janice Schmidt

Ron Schmidt

Lewis G Scholl

Trey Schutrumpf

Donna Schuurman

Maxine Schwartz

Leigh Schwarz

Diana R Schweitzer

Colby Schweitzer

Greg A Scott & Bonnie

Paisley Scott

Marty Scott

Tim Scott

James E Selby

Astha Sethi

Lucy Shanno

Roger D Sharp

Shahid Sheikh

Joanne Shipley

Rob Shiveley

Richard B Shook

Gary Shumm

Ellen P. Simmons

Patricia Ann Sims

Liz Sinclaire

Suresh P Singh

Rachel Smith

Hannah C. Snyder

Joseph Hoyt Snyder

Dorothy Sosnowski

Cassie Soucy

Mark Soutter

Carrie Spates

Tony and Mary F Spiering

Mark S Stave

Shelley Stearns

Paul Steger

Bill Stein

John Sterbis

Lenhardt Stevens

Lee C. Stevenson

Scott Stevenson

John Stewart

Melissa M Stewart

Linda Stoltz

George Stonecliffe

Peter W Stott

Celine T Stroinski

Carol Stull

MaryAnn Sweet

Roger W Swick

Heidi Tansinsin

John G Taylor

Claire Tenscher

Ned Thanhouser

Amanda Carlson Thomas

Jodi Thompson

Lena Toney

Jen Travers

Seth Truby

Gerry Tunstall

Kenneth Umenthum

David A. Urbaniak

Stephen A. Wadley

Mike L Walsh

Benjamin Ward

Donald G Weir

Cheryl L Weir

Dick B Weisbaum

William B Wells

Steve Wenig

Jeffrey W Wessel

Joe Westersund

Guy Wettstein

Brian White

David White

Joe Whittington

Gordon Wilde

Debra A Wilkins

Thomas J. Williams

Scott C Willis

Harry Wilson

Richard Wilson

Fendall G Winston

Brooke Winter

Verena Winter

David Winterling

Gordy Winterrowd

Ingeborg Winters

Joanne Wright

Cam (Caroline) M Young

Roberta Zouain

Jason Zuchowski

Yun Long Ong, by Anonymous

Katie Barker, by Charles and Louis E Barker

Fred Blank, by Bruce H Blank

Edith Clarke, by Joesph

Bevier

Jane Dennis, by Robyn

Drakeford Wonser

Brian Holcomb, by Sue Holcomb

Marlin Icenogle, by Dick B Weisbaum

IN HONOR OF

Elva Coombs, by Shipley Household

Martin Hanson, by Benson & Brice Household

ESTATE GIFTS

Katie Foehl

Robert A. Wilson Expedition

Grant Fund

Alice Yetka (Byrnes)

IN-KIND DONATIONS

Anonymous (3)

Bob Breivogel

Liz A. Crowe and Grant Garrett

Debbie G. Dwelle

Kate Sinnitt Evans

Tom and Wendy Guyot

Martin Victor Hanson

Duncan A Hart

Freda Sherburne & Jeff

Hawkins

Chris Jaworski

Eric Jones

David L Nelson

Elizabeth Reed

Richard Sandefur

Greg A Scott

John Sheridan

Claire Tenscher

Lena Toney

David A. Urbaniak

William B Wells

Owen Wozniak

CORPORATE SUPPORT & MATCHES

Agriculture Capital

Applied Materials

Broadcom

Edward Jones

Glacier House

Intel

KEEN

Lam Research

McKinstry Charitable Foundation

Microsoft Rewards / Give with Bing

Nike

Oakshire Beer Hall

Household

Paypal Giving Fund

Portland General Electric

Ravensview Capital Management

Springwater Wealth Management

The Standard Timberline Lodge

Wildflower Meadows, LLC

Zillow Group

CORPORATE IN-KIND

Best Day Brewing Better Bar

Johns Marketplace

Never Coffee Lab

Portland Syrups

Trailhead Coffee Roasters

Westward Whiskey

RECOGNITION LIST COMING SOON!

by Patti Core Beardsley

As we enter that magical time of year when the mountains become more accessible, the deserts are welcoming and the hills are filled with color, I am reminded of the cycle of life that we so easily take for granted in nature and in our Mazamas. What cycles of life can there be in the Mazamas you ask? Perhaps every climb is a cycle as we return to basecamp and certainly every season of climbing that matches the cycle of the seasons. But, what of the cycle of generations that grows

with the Mazamas every year. We are curious to hear your stories of being introduced to the Mazamas and introducing others—whether through circles of friends or generational traditions.

In recent years, revisiting Mazama stories documented in past Annuals has raised a lot of curiosity about where those hikers & climbers and their children and grandchildren are in their mountain adventure lives. Outreach to a few coparticipants from the 1970s has brought forth some fun reminisces and opened up a lot of questions we’d all love to explore more.

My story is one of being raised hiking (picture kids with homemade backpacks as soon as they could walk) by two outdoor enthusiasts who found the Mazamas

when they moved to Portland in 1968 and remained involved as hikers, climbers and committee members. Dad applied his engineering way of thinking with other members whilst measuring glacial retreats on the Eliot Glacier, determining variations on routes, and working on the Lodge. Like many Mazamas, his perseverance enabled continuing his adventures well into his 80’s including several climbs with the Mazama Elips (elders in the Chinook language). Mom’s adventurous organizational skills led her to join Mazama outings hiking around Annapurna and through the mountains of Peru whilst pitching in on the Mazama Banquet efforts where members shared their stories in a lively annual event. Together, their enthusiasm led us up and around mountains throughout the Northwest enabling us to meet some of the legendary leaders of the era and their

children whose stories we hope to share here in future issues.

Take, for example, Malcolm Montague, himself a third generation Mazama, inspiring his children (the fourth generation) to hike up and around the mountains of the Northwest including being part of the crew that carried fireworks to the summit for the 75th Mazama Anniversary celebration. His daughter, Ellen, recently intrigued this writer with reflections about the Mazama experiences of her father, aunt, grandfather and great-grandfathers as well as her first and qualifying climb up South Sister at age 11. As many readers might also remember, she described sleeping over at the Mazama Lodge prior to a Mt. Hood climb and the distinct sound of yodeling at 3 a.m. to let the climbers know it was time to rise and shine and ascend. Summitting was not a requirement for great adventure as evidenced by multiple hikes around Mt. Hood with the Girl Scouts—much to her parents’ delight.

Many of these stories of adventures and conservation efforts are documented in Bulletins and Annuals and the Mazama archives, which are themselves great reading. Many reside in the memories of you, the reader, and your mentors/family members. Please help us build upon this initial collection by sharing your “cycle of generations” stories, whether through circles of friends or family traditions. Email us at yourstory@mazamas.org! Not sure where to start? We have some ideas...

■ What is the first hike you remember with your parent/ relative/friend? Where did you go? How did they entice you to keep going? How did that story get told over the years?

■ What inspired your parent/ relative/friend to become a mountaineer and climb leader?

■ What particular adventures do you remember them telling stories about?

■ What goals did they have—which completed and which left for future generations?

Ellen’s father was inspired by his aunt and grandfather. As a third generation Mazama, Malcolm became a frequent climb leader and this writer remembers a North/Middle Sister climb with him where the unexpected wind took care of at least one tent on the Hayden Glacier where the team had set up camp. Malcolm relished time around the campfire sharing stories and was thrilled describing the summit of 10 Alps during an early 1970s Mazama outing that included achieving his life long goal of summiting the Matterhorn. If he left any summit undone, it was the Eiger. The full story of the Swiss Alps outing in the 1970 Mazama Annual is a worthy read.

Malcolm’s grandfather, Richard, was one of the early Mazamas and inspired multiple descendants to be active outdoors people, historians, and conservationists. Ellen remembers her father along with close co-leaders and friends Carmie Dafoe and Peg Oslund demonstrating the Mazama ethics of truly caring about those on their climbs by “running the line” of the whole team checking on their progress, thus doubling or tripling their own mileage on any trip—with a smile.

Last year, Ellen had the opportunity to travel the Grindelwald to Matterhorn route that her father so fondly remembered, and she also visited the shop where Malcolm borrowed an ice ax and, along with several members of the outing, had one made. That recent trip included the next generation who are now inspired to pursue their own Mazama adventures in the future. Perhaps a future generation will reach that Eiger summit with Malcolm in mind.

As we look forward to learning more about multi-generational Mazamas, I am grateful for our part in the cycle. I met my

■ How has the love of the mountains been passed down to subsequent generations?

Email us at yourstory@mazamas.org

other half of “generation #2” in a Mazama rafting class. He was an avid adventurer and mountain rescue guy who, upon meeting my mid-70s Dad on South Sister said “yikes, do you expect me to be that active at that age?” We continue to enjoy adventures with nephews, great nephews and our son who became a Mazama in his own right after a three day outing to the top of Old Snowy when he was an adventureappropriate age of 4 and was distracted by “playing soccer” with a pinecone going up the trail. We leave our first generation Mazama family members’ unfulfilled mountain dreams (the Tour d’ Mt Blanc and the Baltoro Glacier) to retirement and these subsequent generations.

by Ryan Reed

Maybe you first saw it at the Mazama Lodge: 16 pairs of names and elevations in descending order, bold and clear in black ink on your lasagnastained napkin. Or maybe it was printed on the side of a water bottle. For some, it’s just a list of notable regional peaks, another trivia quiz like “Ten Largest Lakes of Africa.” For others, it’s a call to action.

Ian McClusky remembers it exactly, as a BCEP student at the lodge. “My eyes scanned down the list [on the napkin]. Some mountains I had grown up with: Mt. Hood, Saint Helens, Mt. Adams...some I knew from a distance, some I had never heard of. Where was Stuart? Shuksan? Glacier Peak? In my hand was a simple list, but it represented the entire homeland of my Pacific Northwest. I realized that to truly know my birth land, I would need to know these mountains up close. In my hand was an invitation.”

That list, of course, is the “16 Major Northwest Peaks.” The Mazamas has an award for summitting them on official climbs, along with awards for the seven in Oregon, and the three most local volcanoes—the “Guardian Peaks.” And there’s the Terry Becker Award for leading official climbs of the 16.

A lot of ambitious Mazamas set out to climb as many of these as quickly as possible. They may find delight in other peaks, or make their own bucket list, but these iconic summits persist in the mind. Many Mazamas know where they are on the list, whether they’re pursuing it or not.

Surprisingly few finish. Since its inception in 1935, only 497 members have received the 16 Peaks award. Another 733 members have completed the Oregon Seven, while just over 2,000 have received

the Guardian Peaks Award. (The awards must be applied for, so it’s anyone’s guess how many have earned an award but not requested it. And there’s another unknown cohort who’ve summited the peaks but not all on official climbs.)

But the number of awards given out has been trending south for several decades.

Guardian awards averaged 50 per year during the 1960s and 1970s; the last 20 years, only 6 per year. In the same time frame, Oregon Peaks dropped from an average of 17 to 3, and the 16 Peaks from 11 to less than 4.

What gives? Are these awards too hard to achieve? Are they anachronistic?

Should the Mazamas discontinue them, or perhaps expand recognition to different peaks? We asked a few dozen awardees for their opinions, and got quite a response.

“I think the award is special,” says Amy Brose (16 Peaks, 2014). “It takes ages to make the 16 Peaks happen, it's a pretty great accomplishment for a Mazama.” But it was more than just a tick list. “The adventures contained in that award are pretty special.”

For many, the Guardian Peaks was a gateway into mountaineering. “I first learned about the 16 peaks in my BCEP class,” says Patrice Cook (16 Peaks, 2016). “I had an amazing leader, Dean Lee, who provided an opportunity for any of his students that wanted to earn the Guardian Peaks award in their first summer as a Mazama. It was a huge incentive.”

We asked a few 16 Peak Award recipients to reminisce about their journey to the award. Note: The Terry Becker Award, created in 2000, is given to climb leaders who lead the 16 Peaks. The Leuthold Award recognizes outstanding contributions to the climbing community in addition to leading the 16, and recipients must be nominated and approved.

David Zeps (16 Peaks, 1998) says the award “gave me credibility with the students in my BCEP groups early in my Mazama career. The bottom line is that awards do confer status, and for instructors, credibility within the organization.”

The Becker Award is clearly a strong motivator for climb leaders. “I’m definitely planning on leading the 16 peaks,” says Forest Brook Menke-Thielman (Guardian Peaks, 2021). “I think it’s a motivator, because once you have the skills to do it, leading a Mazama climb takes more energy than just doing it with friends, but doing it for the organization where you meet new people, and can be recognized for your achievements becomes the motivator. So yes, I do like the awards.”

The effort can form connective tissue between members and climb leaders. “For me to get it, many climb leaders had to accept me on their climbs and

reach difficult summits, and then I had to organize and lead a bunch of them too,” says Amy. “It really kept leadership stoke high for all involved.”

For Ian McClusky, the 16 Peaks Award was a way of connecting to Mazama history. Early Mazama climbers endured multi-day approaches and climbed with alpenstocks and hobnail boots. “These people were bad-asses,” he says. “Although summiting these peaks is infinitely easier today with modern gear, the act of going into the alpine and reaching a summit is still fundamentally just as profound. To complete the Mazama 16 Peaks was, for me, a way to connect to this heritage of mountaineering, and add my name into a hallowed list of those who blazed the way.”

So why then do so few earn the awards these days? There are certainly some objective factors.

The average number of climbers on a team declined sharply in the 1970s with the advent of self-imposed and designated wilderness limits.

continued on next page

It took from 1987, when I took BCEP, to 2004, when I finally climbed Shasta. I’m not sure when I started to think about the 16 peaks. Maybe around 1997, at which point I had climbed all but three, many several times. At that point I started to try to include the remaining ones on my schedule, but it took me until 2004 to finally get Shasta after seven tries— including at least three times that we turned around before the summit due to bad weather or route conditions.

TIM SCOTT (2006, BECKER 2013)

I summited Mt. Hood in ‘99 and Mt. Shasta in ‘06, so it took 7 seasons. The 16 was more of a framework of worthy objectives. During 2001-03, I climbed a lot with Terry Cone and he was all about the 16 peaks. He was a big influence because he took me on all the climbs I applied for.

BOB BREIVOGEL (1997; BECKER, 2001)

It took 15 years, but I only applied for the award when I had led the 16. My hardest 16 Peak lead was Liberty Ridge on Mt. Rainier.

16 Peaks, continued from previous

The Forest Service no longer permits BCEP “Graduation Climbs” of Mt. Hood, which used to start a large number of climbers on their way to the Guardian Peaks award.

Half the 16 now require permits secured (or won in a lottery) in advance, complicating the scheduling for climb leaders.

A thinner climb schedule, still recovering from the pandemic, slightly less popular 16ers like Olympus, Stuart, and Glacier, often accomplished just once or twice a year.

Global warming is shifting and shortening the climb season for many peaks. “I believe [the 16] is getting harder,” says Joe Whittington (16 Peaks, 1992). “Climate change is affecting the routes, and the weather just seems more uncertain.”

The awards may also be suffering from a decline in awareness. Tim Scott (16 Peaks, 2006) points out that the awards presentation has lost its original venue, the Mazama-only Annual Banquet, moving to first the Portland Alpine Fest’s Summit, then to the Volunteer Appreciation night, which has yet to attract the broader membership. “It's become a night for the Old Guard to gather and chat,” says Tim. “It feels insular and not a lot of new blood shows up.” One result is that newer

Mazama members aren’t exposed to the awards.

Amy Brose received her award, unusually, at a BCEP lecture at Jackson Middle School: “All those brand-new people being introduced to the Mazamas at that lecture got to see someone get an award that took ten years of hard work and fun. I'm hoping maybe it inspired a few of the BCEP students to aim high and climb a bunch out of BCEP when they were done.”

There may also be an expectation that the awards are automatically assigned in the Mazama website, like other badges. This may be an eventual option, but for now members must still request the awards.

But few of these factors can fully account for the long-term decline since the 1970s. What about cultural and generational factors? Certainly, there are other outdoor sports attracting our attention: trail running, ultra-marathoning, rafting, mountain biking, and of course rock climbing. “The 16 Peak Award just isn't the grail it once was,” says Rick Craycraft (16 Peaks, 1994). “First off, the world seems to be being taken over by rock climbers, and the patience and commitment about waiting through possibly years of climbing to get the award is not in fashion like it once was.” One could also point to a

AMY BROSE (2014)

It took me 10 years. I got lucky on the big ones. Olympus once, early on after BCEP, with super heavy new-climber gear, and we made the summit. Made it to the top of Glacier, Jefferson, Shuksan, and Baker on my first try each time. Those are often the hard ones for people to get...I was grateful that leaders trusted my skills and took me on these big climbs and were really organized and knew how to make the summits happen.

I had a failed first Rainier climb (a Mazama climb), but two weeks later went back and did it with friends as a private climb and summited. And two years later did it again as a private climb. I finally decided that I might as well lead it as an official Mazama climb so it could count for my 16 Peaks Award ... so I did. And we got it. That’s still one of my proudest accomplishments, and not just as a climber.

As someone who grew up here with a family who did absolutely nothing outdoors and thought mountains were put there to kill people, never in my life did I imagine that I’d not just be climbing all these Cascade peaks but actually leading a climb up Rainier ... Without the 16 Peaks award as a goalpost, I probably would have just kept leading it as a private climb. Instead, I made it an official Mazama climb and others benefitted as well.

It would be a huge omission if I didn’t recognize John Godino for his lead on my last of the 16 peaks: North Sister. I was terrified of it, so many people have been hurt climbing it, but John had that mountain dialed in terms of protection and a climbing plan. It was probably the most fun I’ve ever had in camp (we did a ‘no dehydrated food potluck’ in camp the night before and ate like kings), we sang stupid Bon Jovi songs on our way up the glacier as the sun came up, and the climb went up with no issues. I sat on that summit and felt a huge accomplishment when I realized that I had finally knocked out the 16 peaks with the Mazamas.

society-wide decline in civic organizations, and to the ability of recognition-seekers to post their accomplishments on social media.

Still, other climbing organizations manage elaborate lists of peaks and dole out pins, badges, plaques, and even paperweights for member climbing achievements – the Mountaineers give awards for about 30 different peak lists, the Sierra Club at least 16. Many climbers avidly pursue summit groupings—there are hundreds detailed on the website peakbagger.com.

The expansion of the climbing awards came along with the birth of the Climbing Committee in 1934–35. Until then, all “climbs” occurred during the Annual Outing, a mass excursion to the foot of Mt. Adams, Mt. Rainier, or some other locale for a weeks-long encampment marked by nature walks, campfire theatricals, folkloric reenactments, singalongs, and, yes, climbing. Any other hike or a climb came under the jurisdiction of the Local Walks Committee. As the demand for climbing ramped up, Local Walks was unable to train enough qualified climbing leaders,

But the 16 is no ordinary list. It bears a special relationship to the Mazamas, embedded in its history—and not without controversy. Time for a little history.

Like other organizations, the early Mazamas loved regalia, and awarded special rings, shoulder patches, emblems, and insignia for various accomplishments. Summits were rewarded with satin ribbons printed with the mountain's name and date of climb from at least the 1910s; in 1932 these became the familiar parchment certificates.

Climbing awards for multiple summits started with a book: John H. Williams’s Guardians of the Columbia, published in 1911, an illustrated volume extolling the beauty of Mts. Hood, Adams, and St. Helens. Within two years, the Mazamas were awarding Guardian Peaks badges, a satin ribbon with the mountains’ names and date of climb in gold lettering.

and Mazama members were organizing their own “outlaw” climbs.

To staunch this trend, the Mazamas set up a Climb Committee; among its early actions was to supplement the Guardian award with awards for Seven Oregon Cascade Peaks and Fifteen Major Northwest Peaks (Mt. Stuart was soon added). The motivation was simple; as committee chair John D. Scott bluntly put it: “It should be carefully noted that these Mazama awards are not given merely for making a certain number of specified ascents,” he wrote in 1940. “The mountains are free and anyone of average mountaineering ability can climb all of them. The awards are offered as a direct inducement to promote group climbing sponsored by this particular [organization].”

The committee spent significant time hashing out the associated paraphernalia, settling eventually on “emblem sleeve patches made of blue felt, with one, two

continued on next page

IAN MCCLUSKY (2022)

I was in BCEP [when I saw the napkin list of the 16 Peaks] and had not yet completed an official Mazama climb, but this simple list spoke to my soul. I made a promise to myself: I would climb every mountain on that list.

I was 46 years old at the time. I gave myself an added milestone: climb all 16 by the age of 50. The numbers didn’t really matter: it was more the importance of acknowledging that, at that time, I had the physical ability to push my body; I would not always have that, and I could not take it for granted. Numbers can be arbitrary or meaningful; fifty is just another year, or it’s a major milestone. A lot of people pick major challenges to mark such moments. I took that napkin home and pinned it to my wall. Challenge accepted. I was able to get the 16 Peaks completed in 4 years. Rainier was my third attempt. The first two attempts were with climber leader Yun Long Ong, who had stage 4 cancer. Both times we reached base camp at about 11,000 ft. and both times he was unable to continue. The third time I climbed in his memory, and reached the summit. It was officially my 16th Peak.

The fact that the 16 Peaks span from the North Cascades to northern California gives me a feeling of knowing the entire Northwest region. I feel so much more rooted to the mountains as a regional range. I can proudly stand on one peak and look to the south and north and see at least one or two that I’ve also been atop. Seeing these peaks—not as individuals, but as a family—gives me a deeper appreciation for how all of the mountains are connected.

Deep in the Mazama archives are old alpenstocks, many carved with the names of successful summits and dates. There is a rich history in the Mazamas. In wanting to be a Mazama, I wanted to be part of this tradition. The 16 Peaks, in this sense, meant an opportunity to follow in the footsteps of climbers like Fay Fuller.

Peaks, continued from previous

or three gold starts”—replaced later with parchment certificates. The 16 Peak awardees also received a bronzed metal plaque picturing the 16 peaks and mounted on a wooden base.

The new awards were a hit. As Scott later put it, “The rank and file of [Mazama] climbers took to the award idea like ducks to water. The number of individual ascents registered on the official climbs jumped from a little over 200 to some 350 in a single year.” (Despite the goal of promoting official climbs, a certain number of private climbs counted if long as two members attested to the summit, or if you climbed with another federated outdoor club.)

The 16 were hardly a random selection. Eleven are lofty volcanoes, two are crumbling but dramatic volcanic cores, and the other three are glaciated peaks that dominate significant areas. With the exception of Mt. Olympus and Glacier Peak, they are all landmarks visible from many of the region’s highways and towns. Even today, with more roads and a thoroughly explored backcountry, few would dispute their exceptional stature.

As it happens, the 16 also encompass a wide range of climbing experiences. Seven include glacier travel, six have low-grade technical rock, and three involve both. Two

require multi-day approaches; two ascend into the thin air of 14,000 ft. Four can be considered non-technical, accessible to those with limited training.

Significantly, most of the 16 were wellknown from previous Annual Outings, and all offered reasonable access for the era. In fact, they comprised the vast majority of official climbing objectives through the early 1950s. In a typical year, 1940, only ten official climbs were offered—each attempting one of the 16.

Only 20 members earned the 16 Peak award in its first decade, and it typically required 20 or more years to complete the set. As the climb schedule grew, the time and effort required plummeted, and during the 1960s and 70s upwards of 80 members received Guardian Peaks awards annually, and 16 Peak awards averaged ten per year.

Despite the subsequent decline in award numbers, there’s a reason the 16 persist as a recognized goal, says David Zeps. “There are, of course, much more difficult peaks (and routes) in the Northwest. But the 16 majors are achievable with persistence, reasonable effort, and relatively low risk, so represent a worthy goal for Mazama members.”

But there’s always been some discord about the honors. John D. Scott addressed

My approach as a freshly minted Basic School graduate in 1989 was to treat the list as a survey course. I knew very little about the mountains of the Northwest, so I just thought I’d do this representative list to judge what I liked and what I didn’t. I guess I was defining myself as a climber. I applied for climbs aggressively in 1989, and during that season I climbed half of the 16 peaks. From there on, my connections with climb leaders and reputation as a quality party member carried me along. I thought I had completed the list in July 1993 by climbing Rainier after two previously unsuccessful attempts (including being pinned down by a blizzard in Emmons Flats for 36 hours). But then it came to light that I had not summited Stuart in 1990 as I had thought, in reality only getting to the false summit in thick fog. Fortunately, I had already signed up for Stuart two weeks after Rainier, and that was the 16. I was a little embarrassed at the next Annual Banquet receiving my award surrounded by seasoned climbers.

My only goal when I started climbing seriously in my 50s with the Mazamas was to memorialize my mother on the summit of Mount Rainier, as she summited “The Mountain” in 1948 after spending a summer working at Paradise. From there the peaks’ summits simply compelled me!

[The award] was an unintended achievement that accompanied the joy (and challenges) of climbing and playing in the mountains. After summiting about 8 of the 16, I gradually felt driven to pursue the award, knowing I intended to climb the more famous peaks anyway, and it seemed a challenge worth pursuing.

the divide directly: “There are always some purists in the out-of-doors fraternity,” he wrote in We Climb High (1965). “There are mountaineers who are revolted by the idea of gaining an award for climbing. But the vast majority of us (ignoble mortals!) are more than willing to pursue a lovely award.”

In 1926, an award for climbing the five Oregon peaks over 10,000 feet was proposed, as well as a “Guardians” association within the organization; in response, L. A. Nelson argued that awards would push unqualified climbers into danger and result in loss of life. “When mountain climbing becomes a contest and not a sport, dire results are sure to follow,” he wrote in a letter to the Bulletin “A mark of distinction for achievement in mountaineering is all very well, but it should be a reward and not an objective.”

In 1954 the Climb Committee expanded the awards, authorizing a 10-Peak award, adding a 25- and 50-Peak award a decade later, and capping it off with a 100-Peak award (awarded only four times) in 1971; recipients received a parchment certificate, a silver Mazama emblem pin, a gold pin, or a bronzed plaque (picturing, oddly enough, Sinister and Dome peaks). In 1974, the committee voted unanimously to discontinue all of these, citing the excessive time their support consumed, and noting that “the question of worthiness of a particular peak does not arise with the traditional peaks.” Only the 16 had the undisputed status for an award.

The expansionist urge did not go away. In 1994, Richard Denker proposed a “Second 16” award, submitting a list of peaks that included also-rans like Thielsen and Broken Top as well as higher-end goals like Forbidden, Challenger, and Bonanza. In declining the suggestion, then–Climb Committee chair Doug Wilson responded that “even today there are a great many members that would like to see all climbing awards done away with because they feel that climbing should simply be for the joy and outdoor experience, not as a means of recognition or for plaques and certificates.” The current award system, he wrote, “reflects [Mazama] history and allows interested people to set climbing goals without showing an undue emphasis on awards.”

But having just three awards based on a single list also has its downsides,

especially for impressionable beginning climbers. “Not being able to get on climbs is a common member complaint,” Joe Whittington says, “But it's primarily the 16 peaks climbs that folks are upset about not being able to do.”

With fewer climbs on the schedule and the difficulty of getting permits, “it seems a shame to only prioritize the 16 peaks,” says Amy Brose. “There are so many wonderful mountains that made me a much better mountaineer that aren't on that list. Eldorado is still my very favorite climb, I've done it many times, and anyone who has done it with me just fell in love with the climb. It's sometimes a shame that other awesome climbs that aren't the 16 peaks aren't added as much as they should be to the schedule.”

The original 16 served in part to expand the Mazamas’ focus beyond the Guardians to include the greater Cascades; now, ironically, it might be restricting our vision. In his “Second 16” proposal, Richard Denker made a point of including peaks in southeast Oregon, the Wallowas, and British Columbia. (Richard has also compiled a list of Oregon peaks over 7,500 feet with a 1,000 feet gain on all sides, then climbed/hiked all of them, writing an unpublished manuscript about the effort.)

Climb leader Daniel Mick is more blunt: “Are we loving and protecting all the mountains, or just 16 of them?” Daniel is concerned about the rush to climb the same peaks and the consequences of honoring only a limited list. “63 percent of the 16ers are C climbs,” he points out. “That’s out of reach for a lot of Mazamas.” And too many are simple volcano slogs with low fun factors.

Several 16 Peakers acknowledge the limitations but found motivation in other peak lists—no Mazama award needed. “I think the awards are great, but we probably do not need to expand the list,” says Joe Whittington. “There is a website, Peakbagger.com, where people who are into this can record their climbs and receive recognition. It's also a great resource for planning climbs.”

After completing the 16, Joe pursued the 50 state high points, falling just short on a Denali summit day; David Zeps managed to complete the list on his 70th birthday. Doug Wilson, who thought the Mazamas supported enough lists, went on to complete the Rainier National Park 100

continued on next page

JOSH LOCKERBY (16 PEAKS, BECKER, LEUTHOLD 2008)

For me the 16 Peaks was a 25year journey. I followed my parents, who climbed Hood in 1981, and I took Basic School in 1983 [at age 15]. The following year, I became more interested on a Middle Sister climb, as one of the team members was doing his 16th peak. I had just completed the Warrior Peaks requirements [the substitute for the Guardian Award while St. Helens was closed to climbing in the early 1980s], and when I received the award later that year I saw those who received the Oregon Peaks, 15 and 16 Peaks Awards [also adjusted for St. Helens] as well as the Leuthold Award. Being only 16 at the time, I figured to go for the Oregon Peaks Award and wait and see. I earned it a few years later. Along the way, I got to climb with some other current or soon-to-be Leuthold recipients (Larry Stadler, Ed Holt, and Jack Grauer).

A few years later, I abruptly became a climb leader (there was no Leader Development back then). So, I focused on leading climbs I had already done. By Fall of ‘97, I realized I had already led all of the Oregon Peaks. After Terry Becker’s passing, I was on Climb Committee when discussions of the Becker Award took place. It was then I decided to lead the remaining 16 Peaks. They were all “exploratory”, but I had help from assistants who had been there already, especially Shuksan–Fisher Chimneys and Glacier–Frostbite Ridge, which were my two hardest because of bad footwear. Year by year, I whittled away at them, eventually finishing the 16 with Mt. Olympus— the best climbing trip I ever had.

I was not one to attend too many awards ceremonies, so I waited to complete the Becker Award on Mt. Adams the following year. So, in 2008, I finally received the 16 Peaks Award, along with the Becker Award, and Climbing Committee was gracious enough to toss in the Leuthold Award as well. Not bad for the age of 40!

Peaks, continued from previous

and the difficult 100 Mountains of Japan. Rick Craycraft has been inspired by the Colorado 14ers, the Sierra Club Desert Peaks, Jeff Smoot’s Climbing Washington's Mountains, and several other lists.

But there are many who think the Mazamas should honor more climbing accomplishments. Richard Denker thinks awards are a significant motivator. “Years ago, when the Mazamas had a whitewater program, I went on several Mazama raft trips. I remember [talking] about having a whitewater award for those who navigated the Northwest rivers. The consensus was that it would boost interest in the whitewater program. The Mazamas are moving from a climbing club to [an organization] with diverse activities. A set of awards for hiking and any other activity the Mazamas sponsors may help to keep and grow membership.”

Our survey of 16 Peak recipients yielded plenty of suggestions:

Josh Lockerby (16 Peaks, 2008): “I do think some additional awards should be created for those who maybe don't care so much for the technical exposure—like a list of A and/or B level peaks. Another thought is number of years active—which is not a bad goal at all.”

Tim Scott proposes a unique idea: “I'd like to see a 10-, 25-, 50-Mile High