8 minute read

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS OF WOLVES IN OREGON

by Tom Bode

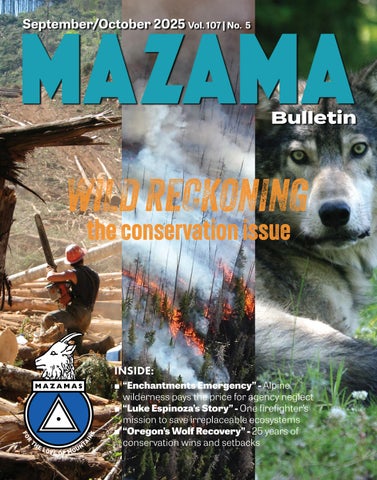

Wolf advocates find themselves torn between celebration and concern. The statistics show why. Take this one, there were only 17 breeding pairs of wolves in Oregon at the end of 2024, the fifth year that number declined from its peak in 2019. Or in the 25-plus years since wolves started repopulating Oregon, only 12 are known to have died from natural causes. Most of the rest were killed by humans (cars, legal and illegal shootings, poison). These facts show the obstacles wolves face. But there is also something to celebrate—wolves actually made a comeback. Even as their presence makes Oregon wild paces more wild and is incredibly exciting to environmentalists and nature lovers, there is still work to do. Wolf advocates aren’t ready to hang a Mission Accomplished banner on an aircraft carrier, according to Rob Klavins with Oregon Wild. In some areas of the state, populations are flat or declining. And although the state’s population overall is growing, legal protections are disappearing.

A brief history

Wolves and humans have been competing for a long time. From the beginning, wolves were winning–hunting prey, raising pups, and howling into the night everywhere in North America. Not anymore. When white settlers arrived in the 1800s, wolves were deemed predators and pests. In the lawless Oregon territory, some of the first hints of government were he “Wolf Meetings” held at Champoeg in 1843, when white male settlers gathered to discuss the problem of wolves and other predators. Anti-wolf forces gathered strength until 1946, when the last wild wolf was killed in Oregon for a $20 bounty.

The story of Oregon’s wild wolf recovery is one of wolves’ perseverance and changing human politics. In the 1990s, the federal government reintroduced wolves to Yellowstone National Park and Idaho, where they thrived. Soon, the wolves were at Oregon’s doorstep. In 1999, a female yearling named B-45 crossed the Snake River in the Hells Canyon Wilderness, the first wild wolf in Oregon in 53 years. B-45 was unwelcome. State officials arranged for B-45 to be chased by helicopter, tranquilized, and transported back to Idaho. It was a short-term solution. Wolves were coming back.

B-45’s appearance turned the starter on the state’s regulatory machinery. The state assembled the Wolf Advisory Committee (1999-2003), which spent two contentious years writing the Oregon Wolf Plan (2003-2005). The 14-member committee that wrote the Oregon Wolf Plan included academics, ranchers, a trapper, a manager of Safeways, a Native American representative, and a politician. Some members outright opposed any wolves in Oregon, while others were conservationists who had spent their entire professional lives advocating for wolves. They had lots to talk through.

he committee composed the plan against the backdrop of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). As long as wolves were listed as endangered, the ESA provided strong legal protections against harassing, injuring, or killing wolves. Even a rancher who caught a wolf in the act of attacking his livestock could not harm the wolf without a state-issued permit. The ESA made the survival of wolves outside of areas of pure wilderness possible. But for the Oregonians who ran cattle and sheep on public land in eastern Oregon, these legal protections were noxious government regulations: they endangered lives and made earning a living more difficult.

Two key disagreements emerged from the committee. First was criteria for “delisting” wolves, i.e. removing them from ESA protection. Second was the control methods that ranchers or the state would use to reduce livestock kills. Control measures range from high-tech, non-lethal approaches, such as light-and-sound boxes activated by wolves’ radio collars, to killing by poisoning, trapping, or shooting. Those two issues remain focal points for wolf policy today.

Disagreements in the committee and in the public meant that the state’s management of wolves would not be science-based. Rather, the committee created a political document that compromised on those issues. Pro-wolf forces prevailed on the issue of control— all but the most notorious wolves would be protected from lethal management as long as the species remained endangered. Ranchers would be required to use nonlethal control methods before seeking to kill wolves or have them killed. In exchange, the committee set a low threshold for delisting wolves.

The state finally adopted the plan in February 2005. At that time, there were no known wolves in Oregon. Then, in July 2008, after an Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife employee spent months howling into the northeast Oregon woods, (a scientifically validated wolf survey method), he heard a chorus of howls and yips all around him. It was a pack of adults and pups; a family of wolves making their home in Oregon. They were back.

Wolves in Oregon today: hanging on, not thriving

Fast-forward to today, and zoom in to the eastern half of the state. Ranchers raise cattle and sheep on arid public lands. Residents are few and include the most vocal of the anti-wolf crowd. Wolves are once again losing the competition with humans. There are fewer packs in the eastern zone than in 2019 and the number of breeding pairs is at its lowest since 2017. In 2011, Congress delisted wolves in part of the eastern zone, allowing lethal management as a matter of course, subject only to state law. This has allowed for more lethal removal of wolves associated with livestock predation. Poaching and unsanctioned killings are a major source of wolf mortality. The numbers reflect the reality: being a wolf in eastern Oregon is not easy.

For anti-wolf ranchers, on the other hand, the situation has improved. With the feds out of the picture, they have an easier time arranging wolf kills with state regulators. And in the horsetrading at the Legislature, the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association is winning big. This year, large bipartisan majorities passed legislation to increase livestock compensation in areas of known wolf activity. If livestock go missing, ranchers can receive the market value of the animal. If the incident is a confirmed or probable wolf kill, the state pays five times market value in compensation. Although ranchers are required to use non-lethal control methods to be eligible for compensation, conservationists complain that the high compensation rates create perverse incentives and promote conflicts with wolves.

Wolves in the western management zone perhaps have an easier time. The politics are friendlie—Sisters has a homegrown “Wolf Welcome Committee” that hosts book clubs and educational events. The nearby Meotlius Pack hasn’t been targeted by poachers; instead an enterprising 14-year-old made local headlines with studying the wolves with trail cams—until this spring, when the pack’s breeding male was illegally killed. Less public land is allotted to ranching, so potential wolf predation is lower. The differences are reflected in state statistics. Breeding pairs in the western zone increased to 7 from 3 between 2023 and 2024. The population is still small—just 49 individuals for half of the state—but it is growing.

Wolves and Mazamas

It shouldn’t be a surprise that many of the Mazamas’ favorite places are also home to wolves. The east side of Mt. Hood is within the range of the White River pack (3 members at end of 2024). The Warm Springs pack (7 members) calls Mt. Jefferson home. Further south, Mt. Thielsen, Mt. Bailey, and Diamond Peak are within the range of the Indigo pack (6 members). The odds of seeing a wolf are slim. State wolf biologists like to say the best place to see a wolf in Oregon is Yellowstone. But they know you’re there.

Wolves don’t like people. Maybe it’s because you stand like a bear, and wolves don’t like bears. Maybe it’s because humans have been hunting wolves for centuries. Regardless, as long as you are following sensible wilderness recreation guidelines, you don’t need to do anything special in wolf habitat (where you may already have been without knowing it). If one sees you, it will likely just leave. Do keep in mind, wolves can act aggressively towards dogs.

Even if you don’t have to change your behavior, perhaps you should. Teri Lysak of Cascadia Wild teaches wildlife tracking and coordinates surveys for signs of wolverines, foxes, and wolves on Mt. Hood. She would like people to be more alert to the presence of animals in the forests. She says, “Instead of thinking ‘this is a nice place to hike,’ I’d like to see more people think ‘this is an animal’s home.’” Lysak’s philosophy is part of a cultural narrative. For her, wilderness cannot be complete without wolves. Their presence demonstrates that a natural world of predator and prey exists in the mountains and deserts, in starkly beautiful contrast with our “artificial” human society. People who don’t like wolves subscribe to a different narrative. To them, protecting livestock from wolves is an opportunity to prove strength and build a livelihood in a hostile landscape. They see the government’s support for wolves as it wrongly siding with predators instead of its citizens.

Coyotes kill more livestock than wolves. Snakes kill more people. Wolves receive more attention than either. For whatever reasons, wolf policy has escaped the realm of science, and now emanates from politics and culture. The future of wolves in Oregon is a quintessentially democratic issue: to be resolved by voters, activists, politicians— and the wolves themselves.