7 minute read

FOREST SERVICE, IN CRISIS, ELEVATES LOGGING AS ITS SOLE PRIORITY

by Sharon Selvaggio, Mazama Conservation Committee member

The last mountain you climbed involved a long approach through a forested landscape before hitting the summit rock, right? And the one before that, and the one before that? What is that forested land? Why is it there? What purpose does it serve?

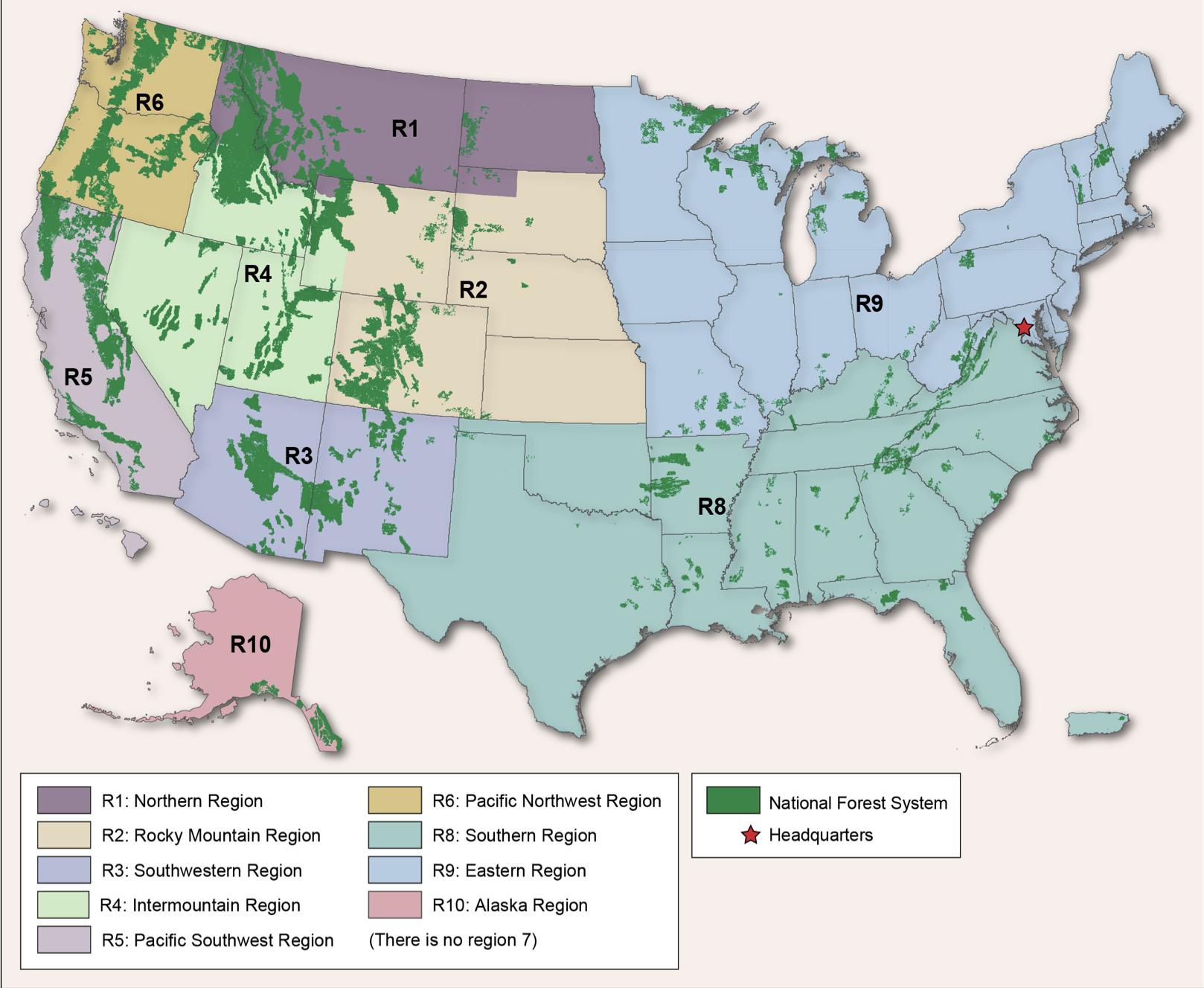

Each of the Mazama Sixteen Peaks is surrounded by national forest land. These are public lands, belonging to every U.S. citizen, and managed by the U.S. Forest Service.

Our own local Gifford Pinchot National Forest, which encompasses both Mount St. Helens and Mt. Adams, was named after the first chief of the Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot, best remembered as a conservation-oriented leader who ensured cut and run forestry would not be the modus operandi of his nascent agency. He saw the interconnectedness of land, water, soil, forests, and people, including future generations, envisioning forests managed for “the permanent good of the whole people.”

As a recreationist, you may see these forests as a network of trails and campsites. But turn on your faucet at home to draw water, likely piped straight from the rivers draining our local national forests. The sweet clean taste is what you get when rain is filtered through deep forest soils, layered for millennia with needle fall. Peer behind the sheetrock covering your walls and you’ll find two by fours—which could have easily come from trees that grew on your local national forest —holding up your roof. Go to the store and you’ll find salmon—birthed in Northwest and Alaskan rivers kept cold for millenia by glaciers and forest canopy. Walk through the forest and you may see salamanders, hear grouse, touch wildflowers, or sense countless other species who evolved in these forests long before humans arrived on the scene. More recently, scientists have realized that forests also play a role in mitigating climate change, by storing carbon in standing trees and soils.

The point is that national forests provide a treasure of interlinked benefits, or under the somewhat wooden language of the National Forest Management Act and its implementing regulations, “multiple uses.” And under law and regulation, the Forest Service is required to balance these sometimes competing “uses”—timber, recreation, watersheds, wildlife, and more—through an interdisciplinary and public forest planning process. Even the restorative spiritual benefits for people spending time in forests are formally recognized in regulation.

Except now, one use is being mandated from the top to swamp all others. Logging. Timber production. Under new policy— which includes two executive orders issued this spring by President Trump, the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act ” (OBBBA) passed in July by Congress, and a secretarial memo issued by Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins, who oversees national forest lands, the Forest Service is now set to massively increase logging.

The OBBBA mandates that in the years 2026–2034, the Forest Service must exceed each previous year’s total timber harvest by an additional 250 million board feet each year, which will nearly double the amount of timber hauled off national forests by 2034. If it all came from the Pacific Northwest (and we can expect that a lot of it will) an estimated 6,000 acres per year would be clearcut just to meet the mandated annual increase.

Sadly, such mandates violate and undermine not only the Forest Plans currently governing each national forest, but also the principle of sustained yield written into national forest law since 1960. But it doesn’t matter. Through the executive orders (EOs) and secretarial memo, the administration has declared an “emergency” for national forest lands, citing threats ranging from national security to wildfire risk to forest health.

By declaring an “emergency” the administration has created a justification for short circuiting normal environmental reviews; forcing fast-tracked endangered species evaluations; and curtailing public involvement. Just to be on the safe side, the EOs also direct the Secretary to repeal any regulations that create an “undue burden” on logging.

While the so-called national security threat has been widely panned as a pretext, national forests do face threats from wildfire, drought, insects, and diseases. These are serious threats that need to be handled by serious, farsighted leaders. But rather than take a thoughtful approach to the real issues facing national forests by utilizing scientific expertise and collaborative public involvement, this administration and Congress are pursuing logging above all else.

Shortly after the EOs were signed, Secretary Rollins made good on the order to repeal any regulation posing an undue burden to logging. She announced her intent to rescind the 2001 “Roadless Rule,” that protects nearly 60 million acres of roadless Forest Service land across the country from roadbuilding and timber harvest. Again, mitigating wildfire risk was the purported rationale. But evidence shows that roaded areas experience more fire ignitions (fire starts) than roadless areas.

The Tongass and Chugach National Forests in southeast Alaska are at special risk if the Roadless Rule is abandoned. Their roadless areas, home to 800 year old Sitka spruce, cedar, and hemlock trees, feed rivers that supply 48 million salmon annually to the commercial fishing industry. Their roadless watersheds contain thousands of miles of clean, cold rivers full of the aquatic invertebrates salmon require.

Oregon State University’s Climate Impacts Resource Consortium finds that rising temperatures due to human-caused climate change are a significant factor in the increase of wildfire in recent decadesand predicts severe wildfire incidents will continue to increase into the future. A serious effort to prevent wildfire would address its primary causes, including climate change. But the “Big Beautiful Bill” not only ramps up logging—it also guts federal clean energy incentives that were starting to make solar a viable option for homes and businesses across the country.

At a time when we need clear data and science-based leadership in the Forest Service, Trump’s 2026 budget request reduces funding by a third, fully eliminating forest research, and state and Tribal forestry funding. Meanwhile, widespread firings and layoffs since February have drained capacity (including firefighting capacity) and morale among Forest Service staff, as with other federal agencies. The most recent news is that all nine Forest Service regional offices are to be eliminated, effectively cutting out the most senior science and resource managers in the agency.

How To Protect Our Forests

The outcome is uncertain. With reduced public input and gutted Forest Service staff, logging operations may happen with little notice.

The Forest Service is in crisis. Its work is being driven by politics rather than by its mission and science. The multiple use mandate is being tossed aside like an empty bag of Cheetos by a careless hiker. The answer to the national forests’ wildfire and forest health problems is not unbridled logging shielded from public scrutiny. There is so much we stand to lose by subordinating the multiple use and sustained yield approach to a timber first and only approach. Everything mentioned earlier—clean water, wildlife and fish habitat, carbon storage—is at risk.

And lastly, while public land advocates successfully beat back a proposal to sell off public lands that had been included in the OBBBA (thank you Mazamas and others!), the threat of losing our public lands, including national forests, still looms, though hidden in the fine print. The president’s proposed 2026 budget justification for the Forest Service proposes to “right-size the federal estate” by “returning” those lands to local governments. Ask yourself—is your local government prepared to take on the management you expect on your Forest Service lands?

WHAT YOU CAN DO:

■ Stay Alert While hiking, watch for new logging or roads. If you spot activity, call the Forest Service supervisor and ask: Why is this being logged? What environmental review was done? How does this prevent wildfires? Consider alerting the National Association of Forest Service Retirees.

■ Show Up Join my postcard and oped writing party at Lucky Lab on SE Hawthorne, Monday September 15 at 7 p.m. (back tables).

■ Use Your Network Know influential people? Whether it’s business leaders, mayors, or brewery executives (who need clean water), ask them to speak up too.

■ Support Conservation Groups Back organizations like Oregon Wild and Bark that fight for our National Forests.