7 minute read

TURNING SUMMIT SNAPSHOTS INTO CITIZEN SCIENCE

by Megan B. Thayne, Dr. Anders E. Carlson, Nicolas BakkenFrench, Oregon Glaciers Institute

Glacier retreat has emerged as a compelling symbol of a warming climate. Across the United States, glaciers often lie in mountains of remote national parks, removed from major population centers, making their disappearance feel equally remote to much of the public. But in Oregon, the story is different. The glaciers on Oregon’s Cascade volcanos—Mt. Hood, Mt. Jefferson, the Three Sisters, and Broken Top—are surrounded by communities that depend on these high-elevation water sources.

Mt. Hood, unofficially cited as the most climbed mountain in the world, serves as a significant gateway for generations of mountaineers that depend on its accessibility and safety for crucial skill development. The other glaciated peaks of Oregon are significant mountaineering targets in their own right, with many of their routes relying on glacier travel. But these aren’t just mountain summits or climbing destinations; they’re dynamic sources of water, refuge, and ecological stability. Nestled high in the alpine, Oregon’s glaciers are frozen reservoirs, storing winter snowfall and gradually releasing it throughout the dry summer months. This steady lifeline supports the rivers, ecosystems, farms, and communities downstream. As climate change intensifies, this lifeline becomes more crucial while also increasingly at risk.

Despite their critical role in sustaining Oregon’s ecosystems and communities— and their increasingly fragile state—these glaciers have long been ignored by federal monitoring efforts and often overlooked in the public consciousness. In the 1980s, the Oregon Cascades were home to 35 named glaciers spread across seven volcanoes. By the year 2000, 34 of those glaciers remained. In the decades since, the fate of Oregon’s glaciers have become increasingly precarious.

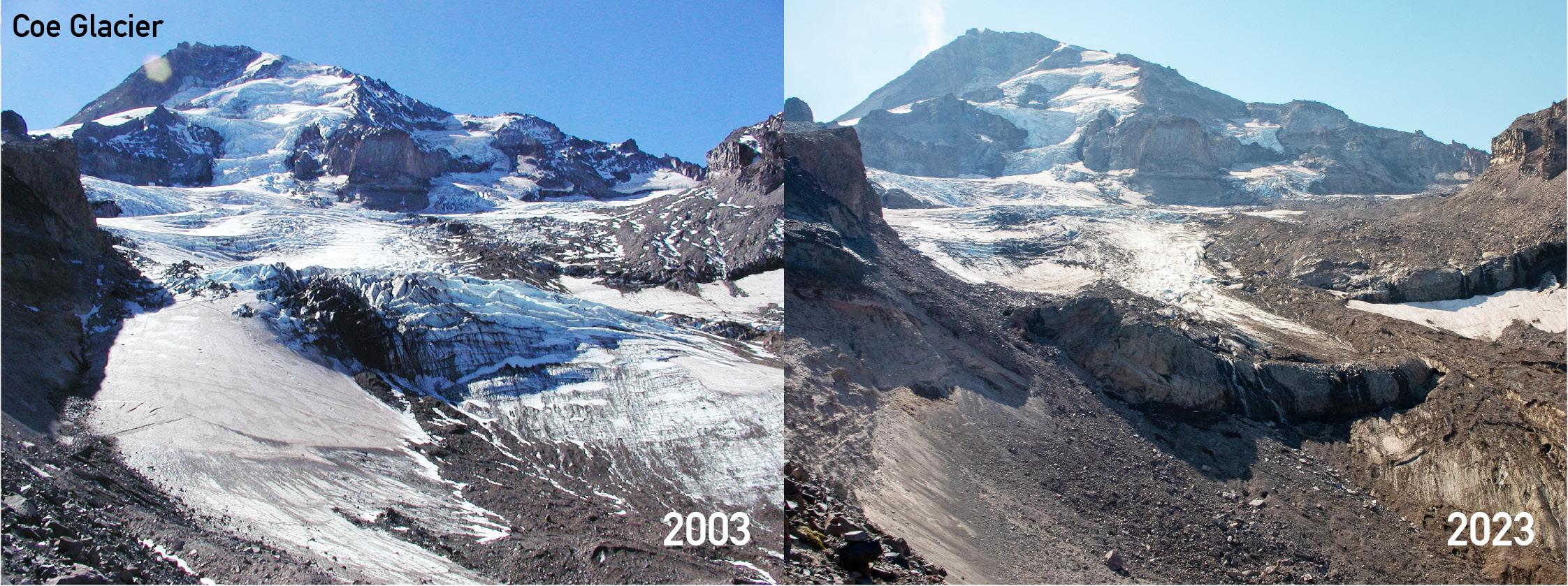

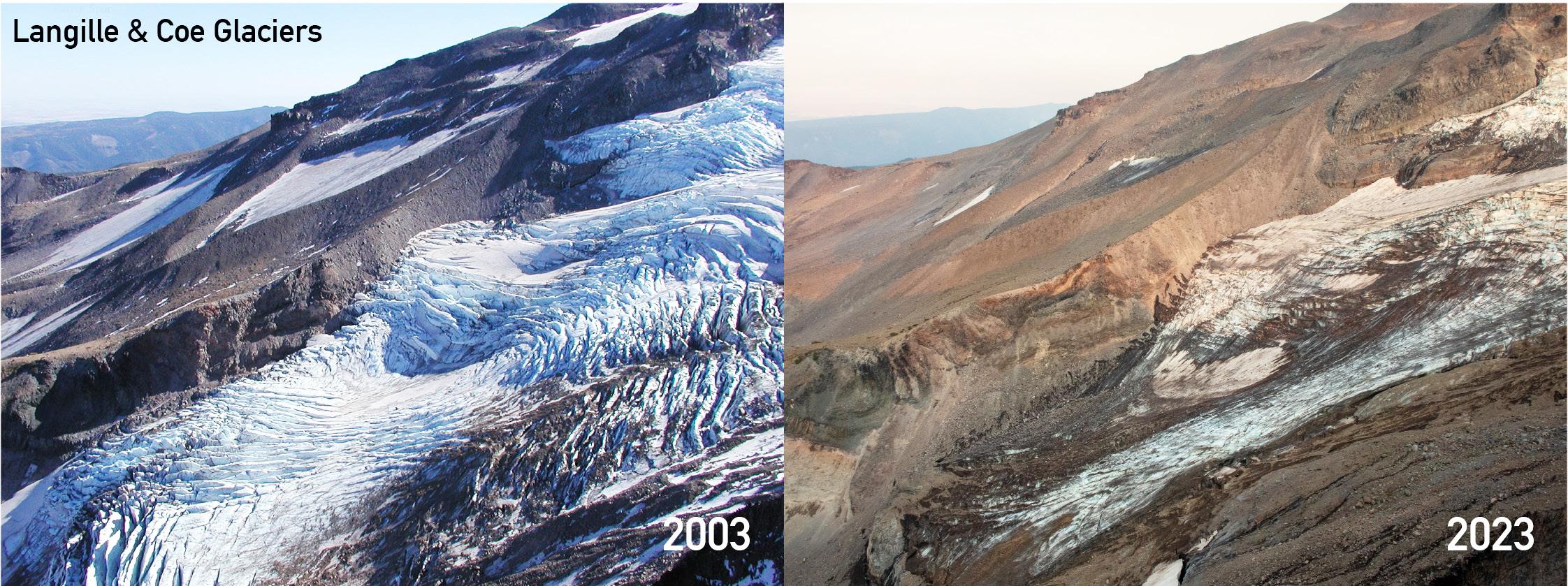

Based on five years of field observations by the Oregon Glaciers Institute (OGI)— supported by funding from the Mazama Conservation Committee—five glaciers have vanished entirely, four are on the brink of disappearance, and eight are now considered critically endangered. In total, half of the glaciers in the Oregon Cascades have either disappeared, are nearly gone, or face imminent disappearance–an alarming shift in just a few short decades. In particular, these glaciers are retreating so fast that physical changes are readily discernible in a span of less than five years. Unlike seasonal snowpack, which renews each year, glaciers hold layers of ice that have built up over decades and even centuries. When a glacier disappears, it’s not just a seasonal shift—it’s a permanent loss. And with it goes a reliable source of summer streamflow that buffers against drought.

Still, for some Oregonians, glaciers remain distant abstractions—firmly fixed in place by nostalgia until some future visit to the mountain. In that detachment, the silent retreat of these glaciers are missed despite the consequences undoubtedly echoing loudly in the valleys below: forests becoming more vulnerable to fire and disease, salmon and trout losing their essential cold water refuge, and irrigation supplies dwindling.

Meanwhile, we live in the golden age of outdoor photography. High-quality cameras tucked into our pockets make it easy to document and share every adventure: images uploaded with a few taps, briefly celebrated, then relegated to cold storage. But the opportunity exists to transform these summit snapshots into powerful citizen science.

OGI was founded on the belief that Oregon’s glaciers merit both attention and advocacy. From its inception, OGI’s mission—to identify the number of glaciers past and present, measure their ongoing health, and project their future—has been propelled by a dedicated network of volunteers and inspired by outdoor enthusiasts. Most notably, OGI’s repeat photography effort was sparked by the curiosity and concern of a Portland-based mountaineer, Mazama, and physician with a master’s degree in glacial science: Dr. Steve Boyer. In 2003, driven by curiosity and concern rather than institutional mandate, Boyer photographed and surveyed the glaciers on Mt. Hood. His images proved invaluable, offering a baseline against which future change could be measured. In 2023, two decades later, OGI volunteers returned to those same vantage points to replicate his photos. The contrasts were dramatic.

Boyer’s self-directed work laid the foundation for a new method of glacier tracking, one powered by everyday people. His legacy now serves as the launch pad for OGI’s GlacierTracker app, a repeat photography initiative that will invite hikers, climbers, and outdoor enthusiasts to contribute their own images to a growing visual archive. GlacierTracker transforms casual snapshots into scientific data, providing many more data points for monitoring glacier retreat than can be achieved by any one small group of people, like OGI’s staff. Each photo becomes part of a growing visual timeline, revealing how Oregon’s glaciers are changing. Participants don’t need technical training or expensive equipment—just the phone they already have in their pocket and the willingness to capture an image. Repeat photography offers a ground-level perspective—one that’s often more intuitive and emotionally resonant. It’s the kind of data that speaks not just to scientists, but to the public. Recognizing both the urgency of glacier retreat and the ubiquity of outdoor photography, OGI saw an opportunity to turn the cultural norm of trail photography into a powerful tool of citizen science— continued on page 38 with the hope of sparking awareness and action.

In 2025, OGI is beginning this citizen science visual archive through 58 repeat photography stations established across all six glaciated volcanoes in Oregon. These stations, documented initially in 2020 and revisited in late summer 2025, will anchor a structured five-year comparison— one made especially resonant by the timeframe itself. That lived memory becomes a parallel reference point, offering GlacierTracker users a striking chance to witness and document how much the landscape has changed since then. Using the GlacierTracker mobile application, citizen scientists will be able to geolocate these vantage points, align with past images, and contribute new photos directly to a central database accessible to the public. Each submission will include observed changes and descriptions from OGI scientists, transforming field participation into real-time glacier education. By facilitating side-by-side comparisons, the app allows users not just to visualize glacier retreat, but to feel it, by matching environmental change with their own lived experiences. And with the opportunity and interest in expanding the use of the application to other regions, Oregon is just the beginning.

GlacierTracker is more than just a data collection tool—it’s a crucial bridge between public engagement and scientific understanding. When individuals contribute a photo, they’re not just assisting with a scientific cause. They’re forming a relationship with the landscape and nurturing an understanding of connection and dependency. Participation in the repeat photography effort transforms passive recreation into active participation, building a community of glacier advocates—people who understand that these icy remnants are not just beautiful, but essential. A photo once intended for social media feeds and memories becomes part of a scientific record and helps to ensure that these ice masses—and the communities they sustain—remain central to the broader climate conversation. Users begin to more consciously understand that our water doesn’t simply emerge from the tap; it originates from these mountains. If a picture’s worth a thousand words, then GlacierTracker, empowered by citizen scientists, will give a powerful voice to Oregon’s vanishing glaciers—articulating a compelling narrative of a changing climate. This vital effort to record and protect glaciers is entering a new phase: one defined not by the absence of oversight, but by the power of community observation and engagement.