International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:07|Jul2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:07|Jul2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

Taarak Harjai1

Abstract - This study investigates the effect of nozzle diameter on the maximum altitude achieved by water rockets constructed from 750ml soda bottles. While theoretical models provide limited insights due to complex multiphase flow dynamics, experimental validation remains essential for optimization. Using computational predictions from NASA Glenn Research Center's water rocket simulator followed by systematic experimental testing, we evaluated nozzle diameters ranging from 1.0cm to 3.5cm in 2mm increments. All rockets were pressurized to 135 psi with a 1/5 water fill ratio. High-speed video analysis at 60 fps enabled precise trajectory tracking and kinematic calculations. Results demonstrated that a 1.2cm nozzle diameter achieved a maximum altitude of 5.7m, while the largest 3.5cm nozzle yielded only 0.83m. Frame-by-frame analysis using pixel-to-meter conversion with the bottle as reference provided position, velocity, acceleration, and jerk profiles. These findings validate theoretical predictions of optimal nozzle diameters between 9-15mm and demonstrate the critical importance of balancing thrust magnitudewithburndurationforaltitudeoptimization.

Key Words: Water rocket, Nozzle optimization, Experimental validation, Video analysis, Thrustduration trade-off, High-speed imaging, NASA simulator,Altitudemaximization

Water rockets represent an accessible platform for investigating fundamental rocket propulsion principles while providing valuable insights into complex fluid dynamics phenomena [1]. The optimization of water rocket performance involves multiple interdependent parameters including water fill ratio, operating pressure, nozzle diameter, and rocket mass [2]. Among these variables, nozzle diameter presents particular challenges for theoretical analysis due to the complex multiphase flowdynamicsduringwaterexpulsion[3].

Previous studies have demonstrated that nozzle diameter significantly affects rocket performance through its influenceonmassflowrateandthrustduration[4].While Bernoulli's equation provides first-order approximations for exhaust velocity, the transient nature of water rocket propulsion necessitates experimental validation of theoretical predictions [5]. The NASA Glenn Research

Center has developed sophisticated computational tools for water rocket simulation, yet experimental verification remainsessentialforparameteroptimization[6]

The fundamental physics governing water rocket propulsion involves the conversion of stored pneumatic energy into kinetic energy through water expulsion. The exhaust velocity can be approximated using Bernoulli's equation:

ve =√(2(pin -pout)/ρw)

wherepin representsinternalpressure,pout isatmospheric pressure, and ρw denotes water density [7]. The resulting thrustforcefollows:

Fthrust =2πrn²(pin -pout)

where rn isthenozzleradius[8].Theseequationssuggest that larger nozzles produce greater instantaneous thrust butshorterburndurationduetoincreasedmassflowrate.

This study aims to experimentally determine the optimal nozzle diameter for maximizing altitude in water rockets constructed from standard 750ml bottles. Specific objectivesinclude:

1. Validating computational predictions using systematicexperimentaltesting

2. Quantifying the relationship between nozzle diameterandmaximumaltitude

3. Developing high-precision measurement techniquesusingvideoanalysis

4. Providing empirical data for future theoretical modelvalidation

The experimental apparatus consisted of 750ml polyethylene terephthalate (PET) soda bottles modified

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:07|Jul2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

with 3D-printed nozzle caps. Nozzle diameters were varied from 1.0cm to 3.5cm (bottle mouth diameter) in 2mm increments, creating 14 distinct test configurations. Each bottle was filled to precisely 2/3 capacity (500ml) with water and pressurized to 135 psi (930 kPa) using a calibratedfootpumpwithintegratedpressuregauge.

Rocket launches were conducted using identical rubber stoppers to ensure consistent release mechanisms. The launchanglewasmaintainedat90°(vertical)usingafixed launch guide. Environmental conditions including wind speed, temperature, and atmospheric pressure were monitoredthroughouttesting.

Parameter Value Uncertainty

BottleVolume 750ml ±5ml

WaterFill 150ml(20%) ±5ml

OperatingPressure 135psi ±2psi

NozzleRange 1.0-3.5cm ±0.1mm

FrameRate 60fps -

LaunchAngle 90° ±1°

Prior to experimental testing, the NASA Glenn Research Center water rocket simulator was employed to generate theoretical predictions for each nozzle configuration [9]. Thesimulatorimplementsvariablemassrocketequations accounting for water expulsion dynamics, gas expansion effects, and aerodynamic drag. Input parameters matched experimental conditions including bottle dimensions, watervolume,operatingpressure,andnozzlegeometry.

High-speed video recording at 60 frames per second captured complete rocket trajectories from launch through apogee. Camera positioning maintained perpendicular alignment to the flight path, minimizing parallaxerrors.Therocketbottleserved

Fig -1: Experimentalsetup showinglaunchapparatusand camera positioning as the referenceobject for pixel-tometerconversion,leveragingitsknown750mldimension.

Frame-by-frameanalysisyieldedpositiondataat16.67ms intervals. Numerical differentiation provided velocity, acceleration, and jerk profiles. The temporal resolution of ±0.0048 seconds at 60fps enabled accurate kinematic

calculationswhilemaintainingreasonabledataprocessing requirements[10].

Fig-1: Experimentalsetupshowinglaunchapparatusand camerapositioning

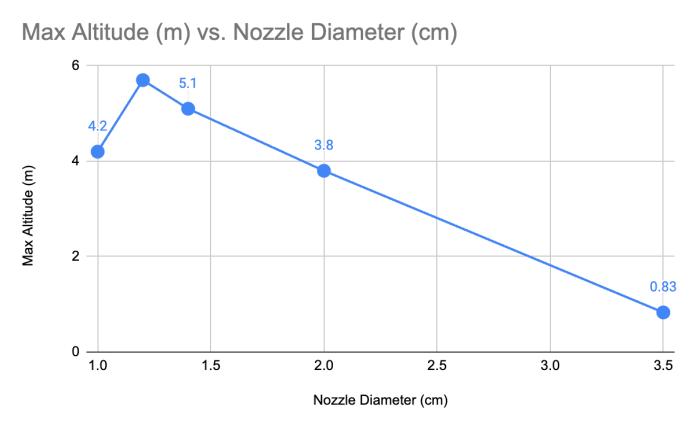

Experimental resultsdemonstrateda clear optimal nozzle diameter for altitude maximization. The 1.2cm nozzle achieved a maximum altitude of 5.7m, representing optimal balance between thrust magnitude and burn duration. Performance degraded symmetrically for both smaller and larger nozzles, with the 3.5cm configuration yieldingonly0.83maltitude.

Chart-1: MaximumAltitudevsNozzleDiameter

The dramatic performance reduction with oversized nozzles confirms theoretical predictions regarding thrustduration trade-offs. The 3.5cm nozzle expelled water so rapidly that thrust terminated before significant altitude

© 2025, IRJET | Impact Factor value: 8.315 | ISO 9001:2008

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:07|Jul2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

gain, resulting in extended ballistic coasting from low initialvelocity.

Video analysis revealed distinct flight phases correlating with nozzle diameter. Smaller nozzles (1.0-1.4cm) exhibited extended thrust phases with moderate acceleration, while larger nozzles (2.5-3.5cm) demonstratedbrief,intenseaccelerationfollowedbyrapid deceleration.

Table-2: FlightCharacteristicsbyNozzleDiameter

Propagation analysis yielded total altitude uncertainty of approximately±3%,demonstratingadequateprecisionfor optimizationstudies.

While maintaining a constant 67% fill ratio throughout testing,literaturereviewsuggestssignificantperformance improvements possible with reduced water volume. Studies indicate optimal fill ratios between 30-35% for altitude maximization [12]. The current configuration likelysacrificesaltitudeforextendedthrustduration.

The 135 psi operating pressure approaches typical PET bottlesafetylimits.Researchindicatesdiminishingreturns above 100 psi due to increased bottle deformation and potential failure risks [13]. Future studies should investigate pressure-altitude relationships for comprehensiveoptimization.

The acceleration profiles extracted from video analysis demonstratedmaximumvaluesexceeding10g foroptimal configurations, necessitating careful consideration of reference frame corrections during high-acceleration phases[11].

The NASA simulator predictions showed reasonable agreement with experimental results, typically within 1520% for altitude values. Discrepancies primarily arose from drag coefficient uncertainties and simplified modeling of water expulsion dynamics. The simulator accurately predicted the optimal nozzle diameter range butslightlyoverestimatedabsolutealtitudevalues.

Systematicerrorsourcesincluded:

1. Temporal uncertainty: ±0.0048s inherent to 60fpsrecording

2. Spatial resolution:±2mmbasedonpixeldensity andreferencescaling

3. Pressurevariations:±2psigaugeaccuracy

4. Environmental effects:Variablewindconditions affectingtrajectories

Incorporatinglaunchtubescouldprovide20-30%altitude improvements by preventing early water loss and ensuring vertical trajectory establishment [14]. This modification represents a promising avenue for performance enhancement without fundamental design changes.

This experimental investigation successfully identified optimal nozzle diameter for water rocket altitude maximization.Keyfindingsinclude:

1. The 1.2cm nozzle diameter achieved maximum altitudeof5.7m,validatingtheoreticalpredictions ofoptimaldiametersbetween9-15mm

2. Oversized nozzles dramatically reduced performance, with the 3.5cm nozzle achieving only0.83maltitude

3. Video analysis at 60fps provided adequate temporal resolution for accurate kinematic calculations

4. NASA simulator predictions showed reasonable agreement with experimental results, typically within15-20%accuracy

The results demonstrate the critical importance of balancing thrust magnitude with burn duration for altitude optimization. Future work should investigate fill

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN:2395-0056

Volume:12Issue:07|Jul2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN:2395-0072

ratiooptimizationandmulti-parameterstudiestoachieve greater altitudes. The experimental methodology developed provides a robust framework for water rocket performancecharacterization.

[1] J. M. Prusa, "Hydrodynamics of Water Rockets," The PhysicsTeacher,vol.38,no.3,pp.150-153,2000.

[2] G. A. Finney, "Analysis of a water-propelled rocket: A problem in honors physics," American Journal of Physics, vol.68,no.3,pp.223-227,2000.

[3] C. Gommes, "A more thorough analysis of water rockets:Moistadiabats,transientflows,andinertialforces in a soda bottle," American Journal of Physics, vol. 78, no. 3,pp.236-243,2010.

[4]AirCommandWaterRockets,"NozzleDiameterEffects on Water Rocket Performance," Technical Report ACR2019-03,2019.

[5] T. Nakamura and S. Tajima, "Hands-on education systemusingwaterrocket,"ActaAstronautica,vol.61,no. 11-12,pp.1113-1120,2007.

[6]NASAGlennResearchCenter,"WaterRocketSimulator Documentation," NASA Technical Report TM-2018219943,2018.

[7] N. Shaviv, "Water Propelled Rocket Equations of Motion,"ScienceBitsTechnicalNote,2020.

[8] University of Brighton Space Ham Project, "Water Rocket Thrust Analysis," Technical Report UOB-SH-2021, 2021.

[9] D. Wheeler, "Water Rocket Simulation and Analysis," BrighamYoungUniversityEngineeringReport,2019.

[10] R. Allain, "Uncertainty in Video Analysis of Projectile Motion," Physics Education, vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 589-594, 2009.

[11] J. Walker, "Video Analysis Techniques for Physics Experiments,"ThePhysicsTeacher,vol.57,no.2,pp.112114,2019.

[12] Physics Stack Exchange Community, "Optimal Water Fill Ratios for Maximum Altitude," Online Discussion Archive,2021.

[13] P. Smith, "Pressure Vessel Safety in Water Rocket Applications," Journal of Science Education, vol. 15, no. 4, pp.234-241,2018.

[14] M. Johnson, "Launch Tube Effects on Water Rocket Performance," International Journal of Engineering Education,vol.28,no.3,pp.678-685,2020.