THE ART OF

Jean R. Brink (2022) Aleksandra Gruzinska (2023) Randel Helms (2022) Sarah Hudelson (2023) Leslie Kane (2022) Shannon Perry (2023) John Reich (2022) Stephen Siek (2023) Ernie Stech (2022) Harvey Smith, Chair (2022) JoAnn Tongret (2022)

Old

emerituscollege@asu.edu

Emeritus Voices is the literary and scholarly Journal of the Emeritus College at Arizona State University. The Journal is intended for the expression, edification, and enjoyment of members of the Emeritus College and others interested in the content. The Journal provides a vehicle for interdisciplinary interaction and education. Submissions are invited for fiction, non–fiction, memoir, essay, poetry, scholarship, review, photography, graphic arts, etc., exploring all facets of creativi ty, scholarship and life experience.

Instructions for submitters can be found at emerituscollege.asu.edu/emeritus-voices/submission-guidelines

Correspondence should be sent to Editor, Emeritus Voices

Arizona State University P.O. Box 873002, Tempe, AZ 85287-3002, or emerituscollege@asu.edu

Emeritus Voices considers for publication letters from its readers in response to articles published in the journal. Letters will be selected on the basis of interest, thoughtfulness, cogency and reasonableness. Letters may be submitted by email or postal mail. See Submission Guidelines in this issue for details.

Copyright © 2022

Unless indicated otherwise, the copyright for each individual article, poem or illustration in this issue is retained by the author, artist or owner (as indicated in the illustrations credits on p. 138).

Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85281

Printed in the United States of America ISSN 1942-3039

Understanding and Maintaining Memory | Billie Enz 5

Live Speeches with Unplanned Humor | M. Scott Norton 22 Mystery Man | Harold C. White 23

An Extraordinary Talent can be a Handicap | Harvey A. Smith 24

A Final French History Examination | Aleksandra Gruzinska 26

Bill Verdini: A Retirement of, Not from, Service 54

Divided We Stood | Doris Marie Provine 28

Eugenics and Its Aftermath | Linda Stryker 39

Our Blood, Our Proof | David Kader 62

The Evolution of Primary Care Medicine in the United States: From General Practice to Family Medicine | Zach Sitton and Eric VanSonnenberg 85

The Choreographic Art of Ann Ludwig 64

The Beep Generation | JoAnn Yeoman Tongret 82 Catherine A. Steele: Apache Educator and Arizona Living Legacy | Christine Marin 97

Golden Days of Hollywood I & II | Paul Jackson 100

The Mice Will Play | JoAnn Yeoman Tongret 102

Sickness Is a Place | Shannon E. Perry 53

The River Derwent | Charles Brownson 77

Mother-kill | Beatrice Gordon 111

Three Poems | Charles Brownson 112

A Small Romance | Gus Edwards 114

Déjà vu: Homeless or Houseless? | Richard J. Jacob 120

All Quiet on the Western Front, My Father and Me | Revisiting the Classics, Review by Ernie Stech 126

It seems that Americans, at least those who need one, have found a new enemy: mandates. Having lived their lives under a myriad of man dates, from federal, state and local governments, school boards, employers and private associa tions, it is deemed repulsive to have to adhere to obligations for the benefit of members, employ ees, students and the body politic generally.

There has, of course, always been in the in dependent American spirit a rebellious reaction to being told to do or not to do something. “You’re not the boss of me!” is a declaration that any parent has heard and that, perhaps in more mature language, most of us repeat into adulthood. And sometimes rightly so. We should oppose constraints that are not from proper authority — that which we democratically have a hand in selecting or from which we have the freedom to separate ourselves. The child quickly learns that her parent really is her boss. The employee knows who his boss is by corporate definition. The child often threatens to “run away.” The employee has the right to quit at the end of his contractual period, if not abruptly.

As citizens, we do have input in the selection of those who mandate, but in our democracy, our personal choice is rejected about half the time. But the mandates still come (or fail to leave.) Quitting, or running away, is a measure taken by a few, opting for other systems and collections of mandates. The costs and risks of doing so keep most of us, however, in our place, disgruntled as we may be.

The new current wrinkle, that raises concern, is that such large numbers have chosen to take the “You’re not the boss of me!” stance against mandates from legally constituted authorities regarding fairly inoffensive measures de signed for the extreme benefit of everyone. Ignoring seat belt requirements, no-smoking rules, minimum driving and drinking ages, education expecta tions, and yes, inoculation requirements of long standing, and being fed false representations from politicians, media and some spiritual leaders, a signif icant portion—enough to make difference—of our co-patriots have chosen to draw the line at the simple act of wearing a protective mask and getting a science-proven vaccine that, if applied to a sufficient percentage of the popu lation, would stave off a pandemic that has already taken the lives of almost 1,000,000 of us.

Who is “the boss of us” in an ICU?

Undemocratic mandates and civil liberties are key themes in articles in this issue by Doris Marie Provine and Linda Stryker. In an autobiographical com mentary on Jim Crowism and a career in civil rights law, Provine describes her intellectual and idealistic progression from an early life in segregated so ciety. Stryker reviews the history of the Eugenics movement and its attempts to thwart personal liberties for a presumed but misguided societal benefit. The theme of social justice is visited more viscerally in David Kader’s poem.

Billie Enz favors us with a written version of her public lecture on memory health and physiology. In their article on primary medical care, Eric vanSon nenberg and his associate, Zach Sitton, provide a history of General Practice in America and its evolution into Family Medicine. Eric recalls for us the role his father played as a GP in their community.

Bill Verdini’s leadership contributions to the Emeritus College and sever al other organizations paint the portrait of a retirement devoted to service. Christine Marin recognizes another who served: Apache educator, Catherine Steele.

Ann Ludwig reviews her career as a dancer and choreographer in our first art feature to highlight the performing arts. But you can have a performance of your own by reading with a friend JoAnn Tongret’s one act play about a burglar and a not very watchful neighbor.

Tongret also brings smiles of recognition in her essay about the beeps in our lives, and you will continue to be amused by this issue’s offering of Ironies and Epiphanies.

We feature our inaugural “Revisiting the Classics” review with Ernie Stech’s impressions of Remarque’s “All Quiet on the Western Front.” Readers are encouraged to supply reflective re views of their own favorites. Also re viewed in Déjà vu is the book/movie pairing, “Nomadland.”

Thought provoking poetry and prose are provided by Shannon Per ry, Charles Brownson, Babs Gordon and Gus Edwards.

Our hope is that you find this is sue to be enjoyable and inspiration al. These are emeritus voices. You are invited to contribute your own.

Making a memory is a multi-step process that we engage in constant ly. From taking in sensory information to interpret your environment, to learning new information such as ever-changing technologies, to recalling the name of an old classmate requires multiple systems in our brain to work together seamlessly. This chapter is designed to provide readers with a greater understanding of the brains intertwined organization and functions, a deeper appreciation of the brains’ memory systems, and finally a discussion of sci ence-based strategies for maintaining memory and brain health.

We are living in an exciting age of neurological discovery. New technologies have allowed researchers to observe the living brain’s function. These data provide researchers with a better way to understand the organization and functional operations of the brain. They have revealed that the brain is a highly organized, complex, multi-functional organ, and nearly all components play a role in sensory intake, memory storage and retrieval. To understand how our memory systems work, it is important for the reader to have a basic grasp of terminology and architecture of the brain.

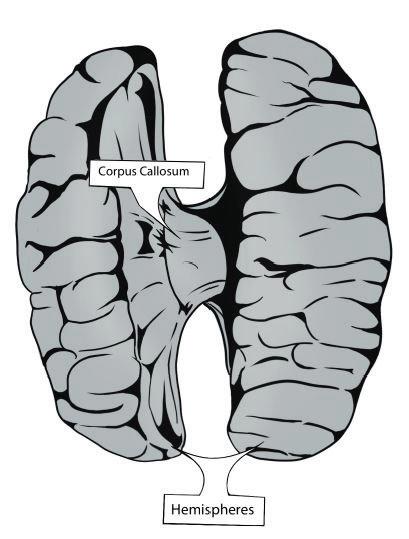

The Hemisperes and Corpus Callosum: At the most basic structural level, the brain is divided into two hemispheres (italicized words are illustrated in the Figures) that are connected by the corpus callosum, a band of nerve fibers which carries messages between the hemispheres integrating information to process motor, sensory, and cognitive signals simultaneously. The brain’s right hemisphere controls the muscles on the left side of the body, while the left hemisphere controls the muscles on the right side of the body. Each hemi sphere performs a fairly distinct set of operations. In general, the left hemi sphere is dominant in language: processing what we hear and handling most of the duties of speaking. The right hemisphere is mainly in charge of spatial abilities, facial recognition and processing music. (1)

The right and left hemispheres are connected by the corpus collosum.

The Lobes and Cerebellum: Each hemisphere is divided into four dis tinct regions called lobes. It is important to remember that no part of the brain is an isolated component that can function without information from other parts of the brain and body. While each lobe has been associated with specific tasks, they are subdivided into interlocking networks of neurons that coordinate overlapping and complex tasks, such as talking, which concur rently requires memory, forethought, and motor coordination of tongue and lips. (Box - Neurons and Neural Networks). All four lobes comprise what is referred to as the cerebral cortex. (2) The following describes the major func tions of each lobe. Notice that each lobe plays a role in learning and memory creation, storage, and recall.

The Lobes and Cerebellum: the lobes extend and cross over both hemispheres.

• Frontal lobes manage higher level executive functions, which include a collection of cognitive skills such as working memory,

attention span, capacity to plan, organize, initiate, self-monitor and control one’s actions to achieve a goal. Towards the back of the frontal lobe is the motor cortex, which is responsible for planning and enacting voluntary movement including speech production in the Broca’s Area. (3)

• Parietal lobes contain the primary sensory cortex, which interprets and remembers sensation such as touch, pain, pressure. Behind the primary sensory cortex is a large association area that interprets fine sensation such as texture, weight, size, and shape. The parietal lobe is also responsible for sensory integration, integrating visual, audito ry, somatosensory, olfactory and taste, which enables us to encoun ter our world as a unified experience. In other words, when we have our morning coffee, we can simultaneously taste and smell the rich flavor, see and hear the coffee pouring into our cup, and feel the warmth as we swallow. The parietal lobe also plays a significant role in allowing us to recall these sensations. (4)

• Temporal lobes: The left side of the temporal lobe contains Wernicke’s Area which is concerned with interpreting/processing/ comprehending auditory stimuli. As we hear the myriad of sounds in our environment, the Wernicke’s area sorts, recognizes, and interprets the meaningful units of our native language. (5) Inter estingly, the temporal lobe is also associated with supporting visual recognition of objects, places, and faces. Finally, the temporal lobe is home to the limbic system, which is responsible for our ability to pay attention, make and recall memories, feel emotions, and respond appropriately.

• Occipital lobes are the seat of the brain’s visual cortex, which allows us to see and process stimuli from the external world, and assign meaning and remember visual perceptions. The occipital lobes gather information from the eyes; this occurs when light proceeds through the pupil. As the light progresses through the pupil, it strikes different types of photo-receptor cells, called rods and cones on the retina. Light stimulates these photoreceptors, which then fire an impulse through the optic nerve, which carries the information instantaneously to the occipital lobe at the back of the brain, where it’s processed and perceived as a visible image. (6)

• The Cerebellum is located at the base of the brain and receives information from the balance system in the inner ear, spinal cord, sensory strip, and the auditory and visual systems. The cerebellum

integrates information to coordinate and fine-tune motor activity and predicts and corrects errors in timing. It is also involved in motor memory and learning, from simple motor coordination such as managing food utensils to complex ballet or basketball maneuvers, to autonomic skills such as word processing and bike riding. (7)

The Limbic System lies deep within our brain between the two hemi spheres of the temporal lobe. The limbic system is responsible for memory and emotion, motivation, behavior, and various autonomic functions, such as the sensation of hunger and thirst and the ability to detect odor through the olfactory bulbs. The last four decades of research have provided a wealth of detailed information on the connectivity and functions of the limbic system, and this knowledge continues to evolve. (8)

The Limbic System: This simple diagram of the limbic system gives emphasis to the main structures known to make up this brain region.

• The thalamus continuously monitors the external environment for input. As massive amounts of sensory information flood the waking brain, the thalamus functions as a relay station, determining what sensory information will receive further focused attention and po tential action, and as important, what sensory input will be ignored. As a regulator of sensory information, the thalamus also controls sleep and plays a major role in regulating arousal, level of awareness, and activity. (9)

• The amygdala may be best known as the part of the brain that drives the so-called “fight, flight or freeze” response. While it is often associated with the body’s fear and stress responses, it also plays a

pivotal role in memory, particularly the storage of memories associ ated with emotional events. (10) Both the thalamus and amygdala are constantly monitoring the external environment for any threat to our survival.

• The hippocampus is critical to the storage of memory. The hippo campus evaluates information, determining if something is worth remembering (long-term memory) and then where to file it so that this memory can be retrieved. The hippocampus is essential in form ing new memories and connecting emotions and senses. The hippocampus also plays a role in consolidating memories during sleep. In addition, the hippocampus appears to serve as a navigator that helps with spatial orientation—in other words, helping us know where we are and how to get from here to there. (11)

• Olfactory bulbs work as odors enter through the nostrils and are absorbed by the nasal mucosa. Information about the scent is pro cessed by the neurons in the olfactory cortex which identifies it. The olfactory sense is the only sense to bypass the thalamus and register information directly with the hippocampus. For example, just the smell of spoiled food can trigger actual nausea and vivid memories of what happened the last time we consumed something that smelled like that. This suggests that the olfactory system once played a vital role in human survival. (12)

• The hypothalamus is constantly monitoring the body’s internal environment for input. The hypothalamus produces hormones that control thirst, hunger, body temperature, sleep, moods, sex drive, and the release of hormones from various glands, primarily the pituitary gland. The hypothalamus regulates homeostasis in the human body, making sure that everything in our bodies is always in balance. For example, if you have had too many salty foods, the hypothalamus gives you a thirst sensation—therefore causing you to drink water to put your system back in balance. (13)

A review of the main components of the brain reveals the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It is important to remember that no part of the brain is an isolated element that can function without information from other parts of the brain/body. While each component has been associated with specific tasks, they are subdivided into interlocking networks of neurons (brain cells) that coordinate overlapping and complex tasks. Likewise, the same can be said about memory. Nearly all the brain components discussed work together to form a multi-layered system of memory.

Memory refers to the processes that are used to encode, store, and later retrieve information. Memory can be broadly divided into three interconnected systems: sensory memory, working memory and long-term memory.

Memory Systems. Memory can be broadly divided into three interconnected systems: Sensory memory, Working memory and Long-term memory.

• Sensory Memory During every waking moment of our life, sensory information is being perceived by sensory organs (eyes, ears, skin, taste buds, olfactory bulbs). Sensory memory is brief, just a few seconds, allowing vast amounts of information to be processed from potentially all sensory organs, simultaneously. Though brief, sensory memory allows us to retain impressions of sensory information after the original stimulus has ceased. For example, think of a firework display, while the experience is brief, we can easily recall the boom ing and whizzing sounds, the beautifully multi-colored explosions of light of various sizes and shapes, and the lingering smell of gun powder in the air. As the sensory information comes in, the thal amus (in the limbic system) plays a critical role in scanning and categorizing the sensory data to help determine what information is important and should receive attention and what information is immediately forgotten. At the same time, the amygdala is evaluating the incoming sensory information, in the context it is occurring, for risk. If these sensory inputs are coming at a celebratory event, it is expected and viewed as safe and exciting; however, should these same fireworks occur unexpectedly (while you are shopping at the grocery store) then they might be considered a danger. (14)

• Working memory is often referred to as short-term memory. Work ing memory is a temporary store for a subset of sensory information to which attention has been applied. Working memory allow for temporary storage and manipulation of information such as doing mathematical calculations or reading a sentence. Working memory has a limited capacity, typically described as seven bits of informa tion (plus or minus two), for a short duration of approximately 20 to 30 seconds. The capacity of working memory can, however, be extended by the process of chunking, in which several items are grouped together into a single cognitive unit, for example, a phone number. The duration of working memory can also be extended by the process of rehearsal in which items are repeated to keep them in working memory for longer than 30 seconds. (15)

• Long-term memory is unlimited in capacity and potentially perma nent in duration. Long-term memory can be divided into explicit memory sometimes called conscious or declared, and implicit memo ry sometimes called unconscious or non-declarative. (16)

Long-term memory can be subdivided into two broad categories Explicit and Implicit.

• Explicit memories are conscious memories that can be recalled and described (declared). They include episodic memory. These memories create the autobiographical story of one’s life such as a first kiss, graduating from school, weddings, first job, etc. Since episodic memories are often laden with emotions they are easily recalled. (17) Semantic memory includes general knowledge that one learns in school or on the job. People tend to store new information more readily on subjects that they already have prior knowledge about, since the new information has personal relevance and can be men tally connected to related information that is already stored in their long-term memory.

• Implicit memories are outside conscious awareness and include procedural memories, such as how to ride a bicycle, type, drive a car, or play an instrument. While initially learning these skills requires a great deal of attention and effort, once learned, these actions are done routinely without much cognitive energy. Implicit memories also include emotional conditioning, often referred to as bias. We have a bias when, rather than being neutral, we have a preference or aversion to people, places, and things. For example, most humans have negative feelings towards spiders, insects, and snakes. However, humans can form bias towards individuals of a different color or culture without conscious knowledge. (18)

Each type of memory is important and serves different purposes. Sensory memory allows us to perceive the world. Short-term memory allows us to process and understand information in an instant. Our most treasured and important memories are held in long-term memory. Our integrated memo ries systems make us who we are as individuals.

Memories are made in three distinct stages. It starts with encoding. En coding is the way external stimuli and information make their way into your brain. The next stage is storage, either momentarily or permanently. The final stage is recall. Recall is our ability to retrieve the memory we’ve made from where it is stored.

Encoding is the first step in creating a memory. It’s a biological phenome non beginning with sensory perception. Consider, for example, the memory of your first romantic kiss. When you met that person, your eyes/occipital lobe registered their physical features, such as the color of their eyes and hair. Your ears/temporal lobe heard their voice. You noticed the scent of their skin via your nose/olfactory system. You felt the touch and warmth of their lips through your skin/sensory strip in your parietal lobe. Each of these separate sensations first travel to your thalamus which evaluates and prioritizes the sensory information. Next, if the experience is deemed important, the separate sensory perceptions are integrated into one single experience in the parietal lobe. (19) Although a memory begins with perception, it is encoded and stored using a vast neural network communication system via electrical and neural chemical signals.

Neurons (brain cells) are the fundamental units of the brain and nervous system. The cells are responsible for receiving sensory input from the external world, for send ing motor commands to muscles, and for transforming and relaying the electri cal and neuro-chemical signals. The electrical signals are carried though the axon, a thin fiber that extends from a neuron Each axon is surrounded by a myelin sheath, a fatty layer that insu lates the axon and helps it transmit signals over long distances between cells.

The electrical firing of a pulse down the axon and to the syn aptic gap triggers the release of chemical messengers called neurotransmitters. These neurotransmitters diffuse across the spaces between cells, attaching themselves to neighboring cells dendrites. Dendrites are designed to receive the electrochemical communications from neighboring neurons. Dendrites resemble a tree-like structure, forming projections that become stimulated by linking other neurons. Each brain cell can form thousands of links, giving a typical brain about 100 trillion fluid synaptic connections. (40)

Networks organize themselves into groups that specialize in different kinds of information processing. As one brain cell sends signals to another, the synapse between the two become stronger and faster. Thus, with each new experience, your brain slightly rewires its physical structure. It is this flexibility, which scientists call plasticity, that can help your brain rewire even if it is damaged. (41)

To properly encode a memory, you must first be paying attention. Let’s consider the “first kiss” example, while the kiss occurred there were dozens of sensory stimuli occurring concurrently; the light, cool breeze, the smell of pizza in the background, the sound and sight of people walking by, etc. Since you cannot pay attention to everything all the time, most of what you en-

the Lecterncounter every day is simply filtered out, and only a few stimuli pass into your conscious awareness. What scientists aren’t sure about is whether stimuli are screened out during the sensory input stage or only after the brain processes its significance. What we do know is that how you pay attention to informa tion may be the most important factor in how much of it you remember. (20)

Storage. Once a memory is created, it must be stored (no matter how briefly). There is a progression: first in the sensory stage; then in short-term memory; and ultimately, for some memories, in long-term memory. Since there is no need for us to maintain everything in our brain, the different stages of human memory function as a filter that helps to protect us from the flood of information that we’re confronted with daily. Hence, most sensory and short-term memory are forgotten and decay rapidly. (21)

The hippocampus is responsible for analyzing the experience (and all contributing sensory inputs) to determine if it is important enough to become part of long-term memory. The various bits of sensory information are then stored in different parts of the brain, for example visual information in stored in the occipital lobe while auditory information is stored in the temporal lobe. How these bits and pieces are later identified and retrieved to form a cohesive memory is still being studied. (22)

Important information is gradually transferred from short-term memory into long-term memory. Information is most likely to be retained if it has emotional force (joy, fear, sadness, disgust, and anger). Another way a mem ory is retained is through repetition. The more the information is repeated, used, or practiced, the more likely it is to eventually be retained in long-term memory. (23) When long-term memories form, the hippocampus retrieves information from the working memory and begins to change the brain’s phys ical neural wiring to consolidate the new long-term memory. Consolidation occurs during sleep, particularly during REM (rapid eye movement). Longterm memory can store unlimited amounts of information indefinitely. (24)

Retrieval. Once information has been encoded and stored in memory, it must be retrieved to be used. Memory retrieval is the process of accessing stored memories. There are many factors that can influence how memories are retrieved from long-term memory. For example, a memory may be initiated through a sensory stimulus:

Walking through the shopping mall the aroma of warm buttery, cinnamon bread lingers in the air. Immediately you are transferred back to your grandmother’s kitchen and for a moment you are in her presence, you can hear and visualize her, in her kitchen in 1958.

The sensory experience that triggers a rush of episodic memories, is called the Proustian moment (named after the French author, Marcel Proust). This is an example of the power of olfactory memory recall. The sense of smell, un like other senses, by-passes the thalamus and immediately triggers the amyg dala and hippocampus and instantaneously a whole orchestra of memories flood to the conscious mind. This type of memory is usually associated with emotional content when it was encoded, and these same emotions will often arise when the memory is prompted by the sensory stimulus. (25)

Explicit memory retrieval, where episodic and/or semantic memories are recalled, usually occurs when you want to consciously remember something, such as the name of someone or answers to questions posed to you. Longterm memory retrieval requires revisiting the nerve pathways formed during the encoding and storage of the memory. How quickly a memory is retrieved usually depends upon the strength of neural pathways formed during its en coding, for example if the event or learning experience provoked some type of emotion, there is a strong probability memory will be easily recalled. (26)

However, “all” of us have experienced challenges with memory recall, for instance the “key” conundrum, or tip-of-the-tongue moments. Forgetfulness is a normal part of aging as shrinkage in the frontal lobe and hippocampus, which are areas involved in higher cognitive function and encoding new memories. However, for most people overall memory remains strong throughout their 70s. In fact, research shows that the average 70-year-old performs as well on certain cognitive recall tests as do many 20-year-olds, and many people in their 60s and 70s score significantly better in verbal intelligence than do younger people. (27) A great deal of memory variability in older individuals depends on brain/body health.

Brain health refers to how well a person’s brain functions across several areas. Including:

• Cognitive health: how well you think, learn, and remember

• Motor function: how well you control physical movements, includ ing balance

• Emotional function: how well you interpret and appropriately respond to others

• Tactile function: how well you respond to sensations of touch

Though brain health can be affected by injuries like stroke or traumatic brain injury, depression, and dementia diseases, there are many lifestyle

changes that make significant difference for maintaining brain and body health. (28) These include:

Annual Medical Exams. Your physical health impacts your cognitive health. Schedule annual health screenings to proactivity detect problems such as diabetes, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure which contributes to cognitive decline. Recent clinical research revealed lowering blood pressure reduces the risk for mild cognitive impairment, which is a risk factor for dementia. (29) During your exam you should also consult with your doctor about your medications (including over the counter drugs) as they may have possible side effects on memory, sleep, and brain function.

Sleep is critical factor for brain/body health. Your brain stays remarkably active while you sleep. (30) Recent findings suggest that sleep plays a house keeping role that removes toxins in your brain that build up while you are awake. In addition to repairing damage caused by our busy metabolism, sleep replenishes dwindling energy stores and even grows new neurons. (31)

Nutrition. A healthy diet reduces the risk of many chronic diseases such as heart disease or diabetes and plays a significant factor in brain health. Recent studies have focused on fruit and vegetable intake and its impact on cognitive function. Research findings have revealed that adequate consumption can prevent cognitive decline, while low intake is associated with increased cognitive decline. (32)

Physical Activity. Studies consistently link ongoing physical activity with benefits for the body, brain, and cognition. Research has revealed exercise stimulates the brain’s ability to maintain old network connections and make new ones that are vital to cognitive health (33) Other studies have shown that exercise increases the size of the hippocampus which is important to memory and learning. Research also reveals that aerobic exercise, such as brisk walk ing or social dance, is more beneficial to cognitive health than nonaerobic exercise. (34, 35) In addition, studies reveal that the more time spent doing a moderate level of physical activity, the greater the increase in brain glucose metabolism—or how quickly the brain turns glucose into fuel—which may reduce the risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. (36)

Social interactions. Our brains need socialization. We need interactions and engagement with others to stay mentally active and emotionally con nected throughout our lives. From the day we were born social interaction has been a major part of cognitive development. We learn how to speak, in terpret, and express emotions, and expand our knowledge from relationships and interactions with parents, siblings, friends, and teachers. As we grow older, socialization is just as important. Building social networks and participat

ing in social activities keeps your mind agile and improves cognitive function. Consistent socialization can even help prevent mental decline and lower the risk of dementia. (37)

Learning Challenges. Continually learning something new has been found to stimulate greater neuron generation and neural network connections in the brain. Neurons are responsible for sending information through out the brain and when this is improved, it positively effects memory, atten tion, thinking and reasoning skills. (38) Fortunately, the concept of “learning something new” is extremely broad, for example academic coursework, learn ing a second language, acquiring skill to optimize the use of technology, new hobbies such as playing an instrument, singing in a choir/chorus, playing chess, or quilting, to more physical skills such as social dance, yoga, or golf. Numerous studies also revealed that when the brain is learning something new, the body is also benefitting, for example reducing stress levels, slowing heart rates, and easing tension in their muscles. And lower stress has wide ranging benefits for seniors’ cardiovascular health, decreasing blood pressure and reducing the risk of a stroke or heart attack, boosting immunity, and lowering levels of depression. Clearly, humans are meant to be learning and socializing throughout their lives. (39)

The brain is the most complex part of the human body and yet our brain relies on the health of the whole body for optimal wellness. This three-pound organ is the seat of intelligence, interpreter of the senses, initiator of body movement, and controller of behavior. The brain is the source of all the qualities that define our humanity. Knowledge of how the human brain is or ganized and how is components function as a complex system is critical to understanding memory systems. Hopefully this new information provides motivation to the reader to maintain a healthy brain and body throughout their lives.

1. Harris, L. J., “The corpus callosum and hemispheric communication: An historical survey of theory and research,” Hemispheric communica tion: Mechanisms and models (pp. 1-60). Routledge (2020).

2. Horien, C., Greene, A. S., Constable, R. T., & Scheinost, D., “Re gions and connections: complementary approaches to characterize brain organization and function,” The Neuroscientist, 26(2), 117-133 (2020).

3. Stuss, D. T., & Benson, D. F., “The frontal lobes and control of cogni

the Lecterntion and memory,” The frontal lobes revisited (pp. 141-158). Psycholo gy Press (2019).

4. (Wagner, A. D., Shannon, B. J., Kahn, I., & Buckner, R. L., “Parietal lobe contributions to episodic memory retrieval,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(9), 445-453 (2005).

5. DeWitt, I., & Rauschecker, J. P., “Wernicke’s area revisited: parallel streams and word processing,” Brain and Language, 127(2), 181-191 (2013).

6. Grill‐Spector, K., Kushnir, T., Hendler, T., Edelman, S., Itzchak, Y., & Malach, R., “A sequence of object‐processing stages revealed by fMRI in the human occipital lobe,” Human Brain Mapping, 6(4), 316-328 (1998).

7. Diedrichsen, J., King, M., Hernandez-Castillo, C., Sereno, M., & Ivry, R. B., “Universal transform or multiple functionality? Un derstanding the contribution of the human cerebellum across task domains,” Neuron, 102(5), 918-928 (2019).

8. Vogt, B. A., “Cingulate cortex in the three limbic subsystems,” Hand book of Clinical Neurology, 166, 39-51 (2019).

9. Jones, E. G., “The thalamus,” Springer Science & Business Media (2012).

10. Fadok, J. P., Markovic, M., Tovote, P., & Lüthi, A., “New perspec tives on central amygdala function,” Current Opinion in Neurobiolo gy, 49, 141-147 (2018).

11. Mack, M. L., Love, B. C., & Preston, A. R., “Building concepts one episode at a time: The hippocampus and concept formation,” Neuro science Letters, 680, 31-38 (2018).

12. Arshamian, A., Iravani, B., Majid, A., & Lundström, J. N., “Respira tion modulates olfactory memory consolidation in humans,” Journal of Neuroscience, 38(48), 10286-10294 (2018).

13. Saper, C. B., & Lowell, B. B., “The hypothalamus,” Current Biology, 24(23), R1111-R1116 (2014).

14. Besle, J., Caclin, A., Mayet, R., Delpuech, C., Lecaignard, F., Giard, M. H., & Morlet, D., “Audiovisual events in sensory memory,” Jour nal of Psychophysiology, 21(3-4), 231-238 (2007).

15. Shiffrin, R. M., “Short-term store: The basis for a memory system,” Cognitive Theory (pp. 193-218). Psychology Press (2018).

16. Squire, L. R., & Dede, A. J. O., “Conscious and unconscious memo ry systems,” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 5(1) (2015). https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a021667

17. Phelps, E.A., “Human emotion and memory: Interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex,” Current Opinion in Neurobiol ogy, 14(2), 198–202 (2004).

18. Prera, A, “Implicit and explicit memory,” Simply Psychology (2020, Oct 26). https://www.simplypsychology.org/implicit-versus-explicit-memory.html

19. Akrami, A., Kopec, C. D., Diamond, M. E., & Brody, C. D., “Posterior parietal cortex represents sensory history and mediates its effects on behavior,” Nature (2018). doi:10.1038/nature25510

20. Uncapher, M. R., Hutchinson, J. B., & Wagner, A. D., “Dissociable effects of top-down and bottom-up attention during episodic encoding,” Journal of Neuroscience, 31(35), 12613-12628 (2011).

21. Norris, D., “Short-term memory and long-term memory are still different,” Psychological Bulletin, 143(9), 992 (2017).

22. Clewett, D., DuBrow, S., & Davachi, L., “Transcending time in the brain: How event memories are constructed from experience,” Hippo campus, 29(3), 162-183 (2019).

23. Bristol, A., & Viskontas, I., “Dynamic processes within associative memory stores,” Creativity and reason in cognitive development, 60-80 (2006).

24. Kensinger, E. A., & Ford, J. H., “Retrieval of emotional events from memory,” Annual Review of Psychology, 71, 251-272 (2020).

25. de Bruijn, M. J., & Bender, M., “Olfactory cues are more effective than visual cues in experimentally triggering autobiographical memo ries,” Memory, 26(4), 547-558 (2018).

26. Tarder-Stoll, H., Jayakumar, M., Dimsdale-Zucker, H. R., Günseli, E., & Aly, M., “Dynamic internal states shape memory retrieval,” Neuropsychologia, 138, 107328 (2020).

27. Gupta, S., “Keep Sharp: Build a Better Brain at Any Age,” Simon &

the LecternSchuster (2021).

28. Nyberg, L., & Pudas, S., “Successful memory aging,”Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 219-243 (2019).

29. Peters, R., Warwick, J., Anstey, K. J., & Anderson, C. S., “Blood pressure and dementia: what the SPRINT-MIND trial adds and what we still need to know,” Neurology, 92(21), 1017-1018 (2019).

30. Malhotra, R. K., & Desai, A. K., “Healthy brain aging: what has sleep got to do with it?” Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 26(1), 45-56 (2010).

31. Spira, A. P., Chen-Edinboro, L. P., Wu, M. N., & Yaffe, K., “Impact of sleep on the risk of cognitive decline and dementia,” Current Opin ion in Psychiatry, 27(6), 478 (2014).

32. Baranowski, B. J., Marko, D. M., Fenech, R. K., Yang, A. J., & MacPherson, R. E., “Healthy brain, healthy life: A review of diet and exercise interventions to promote brain health and reduce Alzheimer’s disease risk,” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 45(10), 1055-1065 (2020).

33. Benedict, C., Brooks, S. J., Kullberg, J., Nordenskjöld, R., Burgos, J., Le Grevès, M., ... & Schiöth, H. B., “Association between physi cal activity and brain health in older adults,” Neurobiology of Aging, 34(1), 83-90 (2013).

34. Erickson, K. I., Gildengers, A. G., & Butters, M. A., “Physical activity and brain plasticity in late adulthood,” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(1), 99 (2013).

35. Teixeira-Machado, L., Arida, R. M., & de Jesus Mari, J., “,Dance for neuroplasticity: A descriptive systematic review,” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 96, 232-240 (2019).

36. Tan, Z. S., Spartano, N. L., Beiser, A. S., DeCarli, C., Auerbach, S. H., Vasan, R. S., & Seshadri, S., “Physical activity, brain volume, and dementia risk: the Framingham study,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 72(6), 789-795 (2017).

37. Hikichi, H., Kondo, K., Takeda, T., & Kawachi, I., “Social inter action and cognitive decline: Results of a 7-year community intervention,” Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 3(1), 23-32 (2017).

38. Leanos, S., Kürüm, E., Strickland-Hughes, C. M., Ditta, A.S., Nguy en, G., Felix, M., Yum, H.. e W Rebok, G.W., Wu, R., “The Impact of Learning Multiple Real-World Skills on Cognitive Abilities and Functional Independence in Healthy Older Adults,” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, DOI: 10.1093/geronb/gbz084 (2019).

39. Zilidou, V. I., Frantzidis, C. A., Romanopoulou, E. D., Paraskevo poulos, E., Douka, S., & Bamidis, P. D., “Functional re-organization of cortical networks of senior citizens after a 24-week traditional dance program,” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 10, 422 (2018).

40. Stiles, J., & Jernigan, T. L., “The basics of brain development,” Neu ropsychology Review, 20(4), 327-348 (2010).

41. Markram, H., “The blue brain project,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7(2), 153-160 (2006).

LecternI think that intelligence is such a narrow branch of the tree of life - this branch of primates we call humans. No other animal, by our definition, can be considered intelligent. So intelligence can’t be all that important for survival, because there are so many animals that don’t have what we call intelligence, and they’re surviving just fine.

Neil deGrasse TysonMost everyone has been present when humor was used by the speaker to make a point or gain the ‘favor’ of the audience. However, some of the most humorous presentations have not been planned in advance. For example, I recall a presenter who was speaking in a school classroom to a small audience of math teachers at a national conference. The speaker stood in front of the room with his notes on a rostrum. As he greeted the audience, a gust of wind came through a nearby window and blew all of his notes from the rostrum to various parts of the classroom floor. Without hesitation, the speaker calmly said, “I would like to open my presentation with a few scattered remarks.” The laughter continued as the speaker moved around the floor to pick up the several pages of notes that had flown around the room.

In an administrative conference I attended at the University of Nebraska, a major program presentation was being held at the university conference center. Approximately 150 attendees were seated to hear presentations by four well-known educators including the president of the local newspaper publication. However, they were having difficulties in setting up the microphone and audio system. The audience waited for over fifteen minutes before the microphone/audio were fixed. Somewhat amazing was the fact that no one in the audience became so impatient that they left the conference auditorium while the problem was being fixed.

After fifteen minutes or so the moderator opened the session by thanking the attendees for their patience but then stated that the technology of the various audio systems in use today has proven to be somewhat troublesome from time to time. In fact, he quipped that using these microphone/audio systems in conferences today is like “Courting a girl through a picket fence. “You can see alright, and you can talk alright, but the contact is not so good!” Laughter from the audience served to set the atmosphere for a highly success ful program session.

During my career at Arizona State University I had heard of Kathryn Gammage, the widow of long time ASU President Grady Gammage, I was told she was a very positive person and one of ASU’s strongest supporters. After the death of her husband, she held positions at ASU, both formal and informal.

I met Kay Gammage in 1993, shortly after my retirement from the College of Business. It was at a social function. We had a comfortable visit and, at the end, to my surprise, she invited me to invite her to lunch. For whatever reason, I took the comment as a simple expression of friendship from a good lady. However, during the next six months, we met two more times, and each time she repeated her invitation. Acknowledging myself as a slow learner, I finally called her and we set a date. I drove to her apartment at Friendship Village in Tempe. At her apartment, I met Sally Y who was a personal assistant and friend of Kay.

As Kay and I drove off, I asked her choice of restaurant, suggesting the upscale Boulders, T.G.I. Friday or McDonalds. She chose T.G.I. Friday as a “fun” place.

The conversation was as easy as it had been in our previous contacts. She was enthusiastic when speaking of her husband and ASU. A major topic was of the 1959 campaign to designate Arizona State College a university. The state legislature, politically dominated by politicians from southern Arizona, refused to approve a name change. The story she told was one I had heard from others, so she must have repeated it often. She and others travelled the state seeking signatures to put the university issue on the ballot. In Gila Bend she asked permission of a pharmacist to place a campaign poster in his shop window. Her request was refused, as he was a University of Arizona supporter. The story was worth repeating, as the campaign was successful and the daugh ter of the pharmacists later became an ASU cheer leader. It was one of the times during lunch when she used her trademark expression, “It was magic.”

Perhaps her favorite topic over lunch was her family. She sparkled when she spoke of her grandsons. She had the same sparkle each time she told the

same stories about them. It was then I appreciated the seriousness of Kay’s declining memory. My empathy for her condition became more personal a few years later when my wife Lucy was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease. Not many months after the lunch, I received an invitation to a book sign ing at the ASU University Club. The title of the book was “It Was Magic. The Kathryn Gammage Stories.” The author was Sally Y. There was a crowd and Kay was placed at the second-floor landing at the top of the stair way. When my turn came to purchase the small volume, I obtained Kay’s signature and then turned to Sally, who was standing nearby. As I handed her the book, she pulled me aside, signed her own name, with the addition “Enjoy the Magic,” and opened to page 36, which was headed “Mystery Man.” In part:

Friday lunch date...

It’s in my calendar I wrote it down.... Maybe I made it up. I’ve done it before....

Oh, he’s here, My Mystery Man.

I’ll say, “It’s so good to see you.

I’ve been looking forward to this all week.”

Handing back the book, Sally said, as if sharing a special secret, that I was the Mystery Man!

While Kay Gammage was waiting for me in her apartment for our lunch appointment, Sally said Kay knew she had a lunch date, but did not know with whom. However, she determined it must be with a man because she had a headache.

Harold—just out of high school—enrolled as a math major at a college with no graduate math department. When they found Harold already knew the most advanced math offered there, they called Penn and asked that some thing be done, and Penn’s department invented a research position for him. I was in the first graduate class he took there. We had common interests in

music as well as math and became friends.

Harold earned a bachelor’s degree, taking mostly graduate courses for his math major, and was admitted to the Ivy League’s most prestigious math PhD program. He often returned to Philadelphia and explained the latest mathe matical developments at his new school to Penn professors.

I invited Harold to a musical soirée at a Penn professor’s home, where our hostess served separate refreshments for vegetarians. As I drove him home, he asked, “Why would someone be a vegetarian?” I explained it as well as I could. He thought for a few minutes and announced, “That’s reasonable. I think I’ll do that!” For years, when Harold was our dinner guest, we accommodated his vegetarian commitment. Suddenly, he announced he was no longer a vegetarian. A student he met in the cafeteria had told him it was unhealthy.

Harold passed his preliminary PhD exam and sought a thesis advisor. A while later he asked me, “Harvey, you solve problems; how do you do it?”

“What do you mean? You must have solved lots of problems in your cours es!”

“Oh no! I have an eidetic memory. I remember everything I read; I even remember what page something was on. I always dropped the course if I couldn’t find the method for solving a problem. Now my advisor has given me a dissertation problem and, of course, there’s nowhere to look that up!”

A dissertation must be an original contribution. If a method for solving it was known, the problem wouldn’t qualify. Harold described his assigned problem. It was out of my field. I was working on my own dissertation and couldn’t offer to help him. (Later, I saw that problem was solved by another of the advisor’s students.) After few months, Harold told me he had given up on the PhD and settled for a master’s degree. Could I help him find a teaching job?

I was teaching at a technical institute that, like his first college, also didn’t have a math major, and they hired Harold. He taught well and was liked by students and faculty. Unfortunately, toward the end of his first year, he sat down at a table in the faculty cafeteria with the President and the Director of Admissions. The latter introduced himself, and Harold unwisely advised him that if any highly talented students applied, they should be rejected so they would go to a good school instead. He was fired at the end of the year. Harold appeared on the verge of nervous collapse, sure that he would never get another job.

Harold visited a friend who taught math at a minor university that, at least, had a graduate math department. An administrator there had just an

nounced a new policy: To avoid choosing majors immediately, all students would take the same courses for their first year. Since not taking calculus would preclude majoring in math or physics later, all must take that course. At lunch, Harold and his friend sat at a table with the math department chairman, and the friend introduced them. The chairman was desperate. As soon as he heard Harold was a mathematician, he asked, “Can you teach calculus? Do you want a job?” When Harold answered affirmatively, he said, “You’re hired!” Harold retired from there in his seventies, having led a happy life, teaching undergraduate courses while pursuing his interests in music and literature. I try to see him whenever we return to Philadelphia.

The month was June and the year 1951, time to graduate after five years at the Lycée français in Barcelona, Spain, with a degree in commerce (business.) I was scheduled to take the final oral examination in French History worth twenty points. Anything from sixteen points on could only be awarded to a professor. There was plenty of room between one and fifteen for the student to shine or fail, with ten points representing a modest but passing grade. The goal was to pass with or without glory, but pass with no less than the required minimum ten points.

I entered the examination room where three imposing intellectuals sat at a table ready to question one of my classmates. Mr. Deffontaines, a wellknown geographer, a world traveler and explorer, was an invited examiner. I approached the table, picked one of the slips containing a mysterious French history question. I then sat next to a window, opened the little paper and read it. I had ten minutes to prepare and ten minutes to present the 1870 War in France. My first impression was that the august body of three distinguished professors made a mistake and that no such war existed. I was ready to tell them so but decided to politely wait until they finished questioning another classmate. By not interrupting, I hoped not to increase his state of nervousness.

I had just lived through WWII and all its violence. For me, French history ended with Waterloo and the defeat of my preferred Romantic hero, Napo leon. Any violence that followed was too close for comfort and registered only superficially in my memory. Nonetheless, I retrieved the name of Napoleon

III, his relationship with Bismarck, the Depêche d’Ems with its declaration of war by France, and Napoleon III’s defeat in 1870. I desperately searched for other details. When my turn came to sit before the distinguished examination panel I had enough material to keep me going for three or four minutes at the most. The panel seemed satisfied. Unfortunately, it had at least six minutes, far too many, for questions. To the first one I responded “Je ne sais pas,” (I don’t know,) and “j’ai oublié,” (I forgot,) to the next one. They finally asked question number three, “Where was Napoleon III taken prisoner?” I tried to avoid repeating my first two answers, so I closed my eyes, bent my head in a meditative position and made an honest effort by uttering the first three elements of a sentence in French in the making, “C’est dans . . .,” it is in . . ., and I hoped for the name of the place to miraculously appear. I went on repeating “C’est dans…” several times, explored my memory without success. Finally, I opened my eyes and looked in despair at the distinguished examination members. They were all smiles. What encouragement on their part! What a magnificent panel I had! Closing my eyes again, I searched my memory in vain, concluding with several more c’est dans . . . . As I next opened my eyes, the panelists said “Merci, Mademoiselle, vous le dites, c’est assez, vous pouvez partir,” (Thank you Miss, you already said it, it’s enough, you may leave.) And they continued to smile.

What did I exactly say that satisfied the panelists? I refused to leave. I had to know and insisted on closing my eyes, searched my memory for the answer and continued to repeat a few extra “c’est dans.” This time, when I opened my eyes, the panelists seemed puzzled and I was politely escorted out of the room very unhappy and greatly puzzled myself.

I wasted no time to locate a Robert Dictionnaire Universel des Noms Pro pres, and looked up in the French dictionary the name of Napoleon III in the cultural section. He was taken prisoner in a city called Sedan which, spelled differently, is nonetheless pronounced exactly as C’est dans. The word remains imbedded in my memory forever. The panelists, however, were left with the impression that I had provided the correct answer, Sedan.

The next day, the surveillant, or supervisor, passing by me in the hall, said, “Quel mauvais examen d’histoire,” what a bad history exam! Nonetheless I met the goal: I passed, of course, without glory.

If there is a lesson to take away from this incident, my best advice to any one, who is given ten minutes to discuss an examination topic, do your best to use the entire ten minutes in presenting your ideas, and leave no time for questions by the panelists.

This is a narrative about growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, when high racial and gender walls were formidable parts of everyday life. It begins with the nearly all-white, highly gendered context in which I grew up. There were moments of clarity about racism, many of which I owe to my mother, an anti-racist who came from a different mold than most of the parents in my community. Sexism and misogyny challenged me directly after childhood, as I sought an adult relationship with the world. I will unpack some of those experiences. It’s strange and wonderful to be alive in a period when the strug gle for equality has gone mainstream with the Me-Too movement and Black Lives Matter. But I think my focus on what came before will demonstrate that both of these movements are built on a foundation that was growing stronger in the 1960s and 1970s, even in the nearly all-white precincts where I lived.

I grew up in the 1950s, in the post-war haze of stay-at-home moms and unacknowledged racism. In my neighborhood, middle-class moms stayed home with their kids unless they endured the shame of divorce and had to find a job and live in an apartment. Grade school and high school were segregated by race— – Ohio law provided that if no one from outside your dis trict wanted in, then your school could keep anyone out. The school district borders were carefully drawn to exclude a nearby Black neighborhood within walking distance of my high school. I was the only black-haired child in my acquaintance, which supported my childhood theory that I was part Native American. I spent a lot of time roaming the woods, making moccasins and bows and arrows, collecting acorns with neighborhood boys for imagined wars, swimming in the summers, and impatiently enduring the confinement of school and church.

I have noticed that mothers figure prominently into many of the lives of academics who come from under-represented groups. In the 1970s, white women also definitely fell into that category. My mother was also an im portant influence, most relevantly here, in her views about race. She married a gentle, loving man stuck in crude southern racism. He grew up poor in a small town in Alabama, in a downwardly mobile family; his father died when he was five years old. His mother took in boarders, and he went to work to help support her before finishing high school. I came to think that he clung

to racism to preserve some vestige of a past in which his family had a se cure place in his tiny hometown. His attitude was general, not specific –ironically, he relied with confidence on a Black colleague in the railroad business, a fact my mother remind ed him of constantly. He was also a sweet and generous father, and he loved my mother. He helped to put her through the University of Chica go when she was 25. He was an avid reader and student of the economy. Nevertheless, I was convinced that if I came home with a Black friend, he would lock the door against me. My mother’s roots were in working-class Toledo. A Democrat, what we would today call a Progressive, she flirted with socialism, and fought my father’s racial bigotry and Republican ideology with evidence and sometimes bitter, ironic humor. These conflicts were never resolved. Their marriage survived for reasons that I didn’t really understand as a kid, probably a shared expe rience of near poverty growing up in the Depression, a cheerless childhood, love of golf and the outdoors, and joy after seven years of marriage, having a daughter, me.

When I was in fifth grade, my mother began teaching social studies in the Cincinnati city schools, soon landing at an inner-city school where most of her students were Black and all were poor. Going to work with a gainfully employed husband in the house was unusual in my tight-knit suburb. Teaching in an inner-city school was unheard of. My mother loved her work and used her position to push for justice in small ways. She took particular pride in helping her “general” track outshine the higher tracks. She taught students how to figure compound interest rates to help them recognize the exploitation that their families faced from discount furniture stores and other businesses that preyed on the poor.

As a kid, I lived a kind of double life, admiring my mother’s work and visiting her school from time to time, but attending an all-white school. She helped me see white obliviousness to racism. One summer, for example, she informed me, on a pledge of secrecy, that several of her faculty colleagues

worked as waiters at the local golf course. They were better educated than most of the golfers, who called them by their first names as they ordered drinks and dinner. She made sure that the Black woman who cleaned our house entered by the front door and I was taught to call her by her full name; back doors and first names were the rule elsewhere in my town. When I was a teenager, my mother took me to hear Reverend Martin Luther King address a virtually all-Black congregation in Cincinnati; that was a big deal for me— –I don’t recall that my father knew about it.

My mom taught me to see racism as a personal failing of whites, my father included. How to address this failing was unclear. Segregation was everywhere, even at my summer job as a carhop at Frisch’s Big Boy. The kitchen staff was almost entirely Black except for a white supervisor. The carhops were all white and female. There was a lot of curiosity on both sides of this racial divide, but I knew to keep my budding race-crossing relationships from work secret from my parents. I left for college in 1964 convinced that I knew of a serious injustice that my white classmates did not recognize, but I had little sense of the tools needed to do much about it or the structural foundations that kept us separate by race.

The venerable University of Chicago was located in the poorer part of the South Side, a long-standing African American neighborhood. Both the student body and the faculty were virtually all white. The university had an inconsistent and incomplete approach to the racial disadvantage and the segregation that surrounded it. Social scientists studied area neighborhoods as a distinct cultural milieu and debated the merits of gentrification, while uni versity officials sought earnestly to achieve a more middle-class environment. The goal was to be regarded as a safe integrated island in this deteriorated part of the city. The student body confronted an uneasy racial quasi-peace in the neighborhood and avoided going out alone at night. One of my classmates died in a daytime drive-by shooting. Despite all this, racism was treated intel lectually, in keeping with the hyper-intellectual traditions of the University.

In my first few weeks at Chicago, I landed a half-time job at the Univer sity’s conference center. My boss was a flamboyantly gay Black man named Thurston Moore. We had many adventures exploring the neighborhood in a little conference center cart. We tooled around neighborhoods that my friends considered unsafe, but Thurston seemed to know a lot of the folks we saw, so I was never afraid. Thurston and an array of non-university colleagues at work helped me feel comfortable in my first year away from home. My grades probably suffered from working half-time throughout the academic

year, but the job helped me stay grounded in Chicago’s intellectual milieu.

I received a top-notch education at Chicago. The faculty seemed to en joy undergraduate teaching. I found a valued mentor in Gilbert White, a world-famous geographer who started a new major in public affairs. There were just four of us in this major, which opened up opportunities to have dinner with famous visitors to the university, including Thurgood Marshall, who was then Solicitor General of the United States. I was shocked to learn from another helpful mentor, law professor Harry Kalven, that the law students had little respect for Marshall, assuming he had gotten his high posi tion through favoritism. This was a moment of clarity for me, having been overwhelmed with Marshall’s brave stories, deep knowledge of our history, and kindness to us students. John Hope Franklin was another influence then because he generously ate dorm food with undergraduate students, in the process teaching us how remembrance and forgiveness can enable a scholar to write about race.

I did my senior thesis on the stark contrast between the pristine and wellstocked Jewell grocery stores in white Chicago neighborhoods and their taw dry, unappetizing counterparts in poorer Black neighborhoods. My advisor, Julian Levi, headed the Southeast Chicago Commission, which concerned itself with protecting the University’s investment in the neighborhood. From the Commission’s perspective, there were no easy answers to the University’s race/class/safety dilemma, but it was striking how disengaged most faculty seemed to be from these concerns.

The faculty also seemed unconcerned with its stark gender skew toward married white men. Almost every one of the few females on the faculty had forsaken marriage and children. In my third year, I was delighted, finally to find an exception, a biology professor married to a banker, and she had children. By this time, I was in love with a graduate student; we married the summer before my senior year. My parents responded by cutting off my tuition, but University officials, appalled at their decision, somehow bailed me out and I graduated on time in 1968. Marriage finally allowed access to birth control; unmarried female students were usually denied a prescription. I was at a loss as to what to do next, with few available role models and no advice, even from a dean who angrily told me that intellectuals don’t worry about such practical matters. I was devastated that a man I knew and trusted had absolutely no advice for me as I faced an unwelcoming job market for women. I feared going into high-school teaching in the Chicago schools, the one profession my mother had warned me against, despite her own apparent

Commentary Analysis/Memoirly happy experience. Then, like many college grads unsure of their next steps, I thought of law school. I was shocked to learn that I would have trouble getting into most law schools because of my gender. This was a long-deferred wake-up call to address gender discrimination, a subject that had never been raised in any of my social-sciences courses at Chicago.

I was admitted to the University of Michigan Law School, thanks to affir mative action or at least a decision to reject discrimination. Our entering class had more than a tiny sprinkling of traditionally absent groups: people of color and white women like me. The faculty were egalitarian and encouraging to a fault, but not all the students. One of the guys I walked to classes with politely asked why I was taking a seat that could have been occupied by a man.

Michigan offered me a counterpoint to what I encountered when I trans ferred after my first year to Cornell Law School. My husband had taken a position in the history department there. Cornell was laissez faire in its approach to race and gender. There was one Black man in the graduating class on law review and a second in my class. The dean of admissions referred to them as “colored.” There were three other women in my own year. No woman had ever been on the faculty. When I would be called upon in class was completely predictable—if the issue involved an incompetent woman. The school’s squash court had a shower—for men. Most pernicious were the job ads that openly asked for male applicants. I nevertheless got a couple of interviews, which concluded when the interviewers said that they couldn’t possibly hire a woman because their clients would never accept it.

It’s hard to explain my feelings at the time. I was a faculty wife with limited prospects for employment outside Ithaca, New York. Some of the faculty had become friends. In class, I grew accustomed to my role as spokesperson for women in legal trouble. My budding legal knowledge was recognized outside the law school through invitations to give talks on the equal rights amendment. But it hurt that none of these friendly people had any concern for my chances at actually becoming a practicing lawyer or were concerned that their placement service was in direct violation of the law. I tore down discriminato ry job ads and integrated the squash-court shower, but why didn’t I do more and why weren’t the law-school faculty concerned with violating the 1964 Civil Rights law??

The women’s movement in my small Cornell world focused then on issues like the Equal Rights Amendment, abortion, and lack of women on the facul ty and even in some undergraduate programs at the university. The veterinary school, for example, accepted only two women per year on the theory that women weren’t suited for large-animal practice. The faculty club did not ad

mit female faculty. There was no weight-room open to women—I was kicked out of the one I tried to integrate. Sadly, the fight for change was more like hand-to-hand combat than an organized campaign that reached across race and class to confront discrimination more inclusively and powerfully. I sensed broad agreement with Erich Fromm’s characterization of women in The Art of Loving, as the emotional center of the family, with the male as the intellectual leader. Higher education, in this line of thought, should be open to women, but it operated on the assumption that the goal was to produce well-educated wives and mothers, like the wives and mothers of many of the white male fac ulty. The possibility that the university could do more to encourage minority students by rethinking its recruitment and admissions processes remained largely off the table.

Being on the receiving end of sexism and misogyny of that era has relatively little in common with the racism of the present. For example, in my insulated white world, interactions with law enforcement were a non-issue. But at another level, some of the confidence-robbing characteristics of an environment that seemed blind to the intelligence and ambition of people who looked like me was dispiriting. The white men with PhDs who ran the university seemed unmoved by the tremendous gender and racial skew in their favor. The idea that more diversity might improve the quality of our lives together had few adherents.

A lot of this changed, sometimes quickly in the late 1970s. Cornell invest ed in a weight room for women and introduced a women’s studies major that brought in a few female faculty members on appointments shared with other departments, though this gave them service requirements in two departments and made them doubly vulnerable to a denial of tenure. In law-school class es after mine, the number of women began to grow significantly. But there was a general lack of appreciation for the way structures kept the status quo intact. The law school, for example, hired its first female faculty member a couple of years after my 1971 graduation, a bright, but naïve, recent graduate in her mid-twenties. During her first year of teaching, she fell in love with a divorced law student ten years older than herself and was promptly fired.

After graduation, I took one of the few attractive options available to me: I became a lecturer and research associate at Cornell. I was the first woman in my department and of a status lower than the regular faculty, but it was fulfilling work for a couple of years. I realized that to ever go further, I would need a doctorate. My husband was on tenure track, and we were thinking about having children. I chose a PhD in political science at Cornell. I decided that

graduate school was the optimum time to have children, having heard terrible stories about inflexible ten ure clocks for women faculty. Both my wonderful sons were born during my four years of graduate school. My mentors, of course, were men – both the political science faculty and the law school faculty were all male and all white in this period. These men, David Danelski, Ted Lowi, and Rog er Cramton, were wonderfully sup portive.

The gender-inflected dynamics of this period came home to me when I went on the job market with my JD-Ph/D combo and received four tenure-track offers. (Perhaps once again, I was a beneficiary of affirmative action as universities were beginning to realize that they needed women on their faculties.) My dilemma was that my otherwise supportive husband wanted badly to stay at Cornell. He made a perfunctory effort to find a position at the two schools I preferred, Ohio State and University of Texas at Austin, but nothing emerged. As a compromise, I took the offer from Syracuse University, a 50-mile commute from the rundown house we bought between Syracuse and Ithaca.

This was a busy time—the house needed a ton of work, the kids were 2 and 4, and I had a one-year deadline to put the finishing touches on my dissertation and graduate. I had a full teaching load. I soon discovered that I was being paid 13% less than a colleague hired at the same time and rank. My department chair refused to budge, and I could think of no way to appeal his decision. I was new at Syracuse University, which had no obvious office or procedure for addressing discrimination. And I was stung by the casual rejection of my complaint by my department chair. I also wonder if I did not actually feel accepted as a full-fledged member of the faculty. I don’t recall even discussing the matter with the one other woman in the department, hired a year before me.

Syracuse University was good to me. I published my dissertation on how the Supreme Court selects its caseload, (1) and then a book comparing lay and lawyer judges while serving as a local judge in my spare time, which grew

Professor Marie Provine teaching Law at Cornell Law School.

out of my election as a town justice. (2) The director of women’s studies and I were given a two-year leave to develop a university-wide policy on sexual harassment, which, much to our relief, was adopted and aggres sively implemented. The University allowed me to spend time teaching abroad, first in Strasbourg, France, then in Madrid, Spain, with an additional summer in Geneva, Switzer land. I was also permitted to take a year off twice for having received two NSF grants. I took two year-long leaves in Washington, DC. I received a huge salary boost on one of these Washington years – apparently the result of a salary study on gender discrimination at Syracuse University.

I rose through the ranks and became department chair. One of my main goals in that role was to get the department to hire at least two African -Amer ican faculty. Helped by my brilliant, resourceful Black graduate student, Susan Gooden, we did succeed in finding two young men willing to be our first Black faculty. Their tenure was short, however. One of our hires was immediately recruited by the administration, and the other decided to move on. This was a bitter lesson in how inadequately prepared our department and University were for change. Ours was a naïve integrationist vision of welcome on the same terms as new white faculty, without regard to the nearly all-white university environment and the location in a declining industrial city sharply divided by race and class. I was more successful in moving an African-American colleague into our department on a half-time basis; he was tenured and already knew the score.

Ironically, research, rather than personal experience, helped me see how structurally embedded racial stereotypes are, and how resistant to change, even in the face of strong evidence of the injustices involved. In 1984 I be came a Judicial Fellow, a one-year post in Washington DC to research issues involving the federal courts. Toward the end of my tenure there, I was alerted by a contact at the Federal Sentencing Commission to an unusual number of judicial retirements and requests for reassignments based on unwillingness to impose the harsh mandatory sentences that Congress had designed for offens

es involving crack cocaine. A few district judges had sought to evade them on the grounds that the large racial disparities these mandatory sentences pro duced violated the Constitution’s equal-protection clause, but the appellate courts uniformly rejected this reasoning. The situation inspired me to leave my intellectual comfort zone, judicial politics, to determine how Congress came up with these penalties. Nothing in the legislation or its official de scription was helpful, but crude racial stereotypes were evident in much of the testimony and reports that Congress had examined. Concern about the vulnerability of white youth to drugs peddled by inner-city Blacks figured prominently in the congressional debate. The rhetoric about these drug sellers was dehumanizing — they were often characterized as rats or vermin. I struggled to find the right intellectual mooring for this research. Racist intent was an elusive framing, so I lay the project aside for more than a decade as life intervened, including divorce.

A few years later, I was invited to Washington to direct the Law & Social Sciences Program at the National Science Foundation. The law and society field, with its attention to social norms, economic injustice and societal struc tures, had long been a refuge for me from political science’s tight focus on the official organs of state power. I had taken leadership roles in the Law & Society Association and I was anxious to “give back,” but very unskilled in the ways of the NSF. Dr. Patricia (Pat) White, director of the Sociology program, in the cubicle next to mine, became my guide, mentor and friend. She edu cated me about the micro and macro aggressions prevalent at the agency and pushed me to use my power to challenge our biggest, most powerful grantee, The National Consortium on Violence Research. The Consortium had been accorded the unusual privilege of awarding NSF research funds to a group of criminologists according to its own criteria. My goal was to stop that passthrough relationship, which involved challenging the Consortium’s powerful director, Alfred Blumstein, a man with deep ties at NSF. This was unpleasant work, but it came with the enormous benefit of getting to know and love a handful of Black criminologists.