8 minute read

Déjà vu: Homeless or Houseless? | Richard J. Jacob

Homeless or Houseless?

Richard Jacob

Advertisement

The Book: Nomadland, Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century, Jessica Bruder. W. W. Norton & Company, New York, NY, 2017 (JB)

The Movie: Nomadland, Chloé Zhao, Director; Frances McDormand, David Strathairn; Linda May, Bob Wells, Charlene Swankie; Searchlight Pictures, 2020.

Driving frequently between Phoenix and Los Angeles, one becomes familiar with the oasis town of Quartzsite. Bisected by Interstate 10 and twenty miles east of the California border and Colorado River, it is a spread-out random collection of gas stations, fast food restaurants and miscellaneous shops. Perhaps one even stops there for lunch. But during the winter, it is also home to thousands of RV’s, mobile homes, trailers of all descriptions, vans, cars and tents, most of which are in desert campsites far beyond the view of those driving through. The residents of these “temporary” homes raise the Quartzsite population from the summer’s 3500 to more than 250,000. They gather in an annual migration from points throughout the United States, most sharing a common circumstance: they have been economically squeezed out of the American dream of owning a “sticks and bricks” house.

For most, many of whom are retirees or the “downsized” unemployed, a nomadic life is their new reality. Indeed, there is a common defiance. In the words of the wheeled nomads’ guru, Bob Wells, who organizes the massive

Crowded Quartzsite campground.

annual “Rubber Tramp Rendezvous” in the Quartzsite desert,

At one time there was a social contract that if you played by the rules (went to school, got a job, and worked hard) everything would be fine. That’s no longer true today. You can do everything right, just the way society wants you to do it, and still end up broke, alone, and homeless.

But by moving into mobile residences, however spartan, “people could become conscientious objectors to the system that had failed them. They could be reborn into lives of freedom and adventure.” (JB, p. 74). Journalist Jessica Bruder began her investigative reporting of these modern American nomads in 2014 by visiting the Quartzsite camping grounds, meeting its residents and following them through their peregrinations over the next three years. Among the many she profiles in her book, one in particular is given top exposure: Linda May, a sixty-something widowed grandmother who, out-of-work and with no pension, Jessica Bruder. chose not to impose longer on her financially struggling daughter and

Jacob | Déjà Vu

Jacob | Déjà Vu her family, and in 2010 began her nomadic life, living out of a tiny plastic 1974 trailer, she called the “Squeeze Inn,” towed by a salvaged Jeep Grand Cherokee.

Bruder interviewed Linda May (and others) extensively, learning of the seasonal employment she and her fellow nomads took throughout the country. This included being camp hosts at national and state parks, agricultural harvesters, and “pickers” in the many enormous Amazon warehouses. Pay is minimal, benefits almost nonexistent and working conditions stressful and, especially for seniors, dangerous and unhealthy. Usually, communal camping space is provided for the workers.

[I scoured the media] for anything about the [“workamping”] subculture. Much of what I found made workamping sound like a sunny lifestyle, or even a quirky hobby, rather than a survival strategy in an era when Americans were getting priced out of traditional housing and struggling to make a living wage. (JB, p. 163)

Much of Bruder’s attention is paid to Amazon’s heavily criticized use of elderly nomad employees. Depending greatly on this source of labor, Amazon has organized it in the CamperForce Program, with an emphasis on the intangibles of team and friendship. Bruder quotes a CamperForce recruitment brochure: “One benefit that’s worth its weight in gold is…building lasting friendships!” But the brochures also forecast the physical and psychological demands of the work: “We cannot stress enough the importance of arriving at Amazon physically prepared.” (JB, pp. 97-98) Walking ten to twenty miles a day on concrete floors while being monitored for productivity was often remarked in Bruder’s interviews. Foot, leg and other infirmities, common to this age group, were universally suffered as the Amazon Campers doggedly pursued financial sustenance for the off season—enough to pay for vehicle repairs, food, space rental and a few comforts.

Bruder drilled more deeply into the story of these modern American nomads during the second year spent with them by buying her own used van, that she named Halen, and tricking it out as a mobile residence, in which she followed, mostly with Linda May, the employment circuit and spent the off season at Quartzsite. She worked at Amazon and harvested sugar beets in North Dakota. She learned where to find free, safe overnight parking— Walmart was a staple—and how to make minor repairs and jerry-rigged conveniences.

Experiences like these were the background music to my reporting this

book. Without living in Halen, I don’t think I would have gotten close enough to people to really hear their stories.

Bruder quotes another workamper, Kat, an Army veteran who lost her job due to multiple sclerosis,

…So many of the folks I talk to in my various RV groups are going full-time because of financial hardship…The new freedom…able to live while reinventing oneself…Is this the evolution of the former middle class? Are we seeing the emergence of a modern hunter-gatherer class

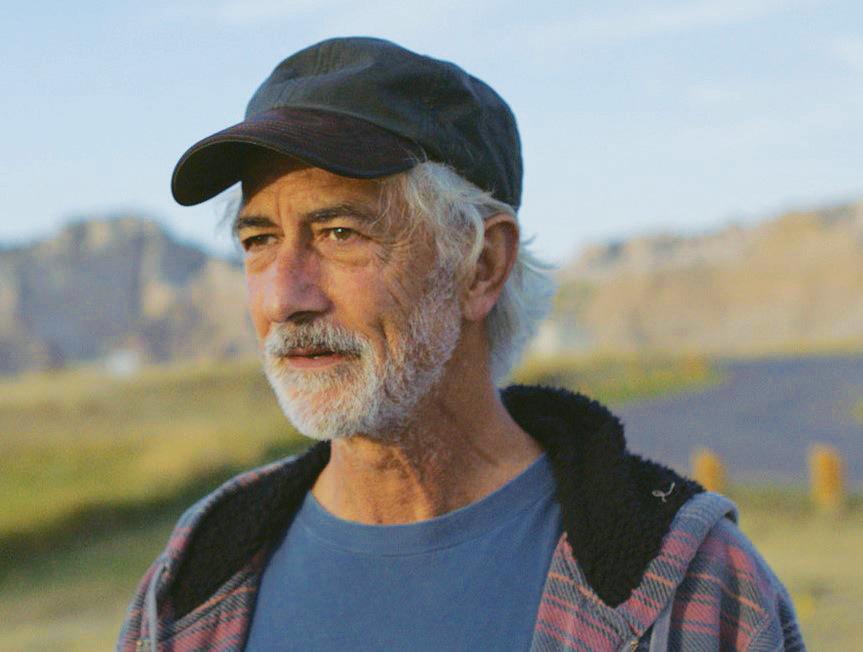

In the Oscar-winnning movie based on Bruder’s book, Linda May appears in a fictionalized characterization of herself, as does the aforementioned Bob Wells and another of Bruder’s principal interviewees, Bob Wells an elderly woman who went by the name of Swankie Wheels (Charlene Swankie.) (In the movie, Swankie sadly dies of cancer; this clearly was not the case in reality, as she played herself.) There are several other cameo appearances by other real members of the workamping community. The main character, however, is the fictional Fern, who had been living the American dream in a model house in Empire, Nevada, where her husband was employed at the US Gypsum plant. But the plant shut down, the company town was abandoned, her husband died, and she found herself houseless and unemployed. Her track subsequently followed

Jacob | Déjà Vu

Jacob | Déjà Vu the story of typical nomads. She buys a van, travels the employment circuit and joins the Quartzsite camping community.

For her outstanding portrayal of Fern, Frances McDormand won the Best Actress Oscar in 2021, her third (Fargo in 1997 and Three Billboards Outside Ebbing Missouri in 2018.) She picked up a second statuette for the film itself as its producer. Chloé Zhao won as Best Director. Just as Fern symbolizes the women, especially the single ones, among the Camper nomads, the fictional Dave (David Strathairn) embodies the men. The basic messages of the David Strathairn. book and the movie are identical, except that the movie diverges into the personal relationship between Fern and Dave, involving as well as their families in the “real” sticks and bricks world. Only the three real personages shared with the book: Linda, Swankie Wheels and Bob, fully exemplify in the movie their nomadic ethic:

Along with many of the wayfarers he came to inspire, Bob saw things differently. He envisioned a future where economic and environmental upheavals had become the new American normal. For this reason, he didn’t package nomadic living as a quick fix, something to tide folks over until society had stabilized, at which point they could reintegrate with the mainstream. Rather he aspired to create a wandering tribe whose members could operate outside of—or even transcend—the fraying social order: a parallel world on wheels. (JB, p. 78)

It is a way of life that few had ever dreamed would be theirs, not while they lived in modern, comfortable houses pursuing professional careers or successful businesses. Foundering companies, outsourcing, recession layoffs, market reversals, health emergencies, coupled with vanishing health insurance and pensions, especially those with defined benefits, left the unprepared and unexpecting with, initially, the embarrassment of being “homeless,” and then the decision to try living on “the road.”

Among the people I met, some had their personal savings wiped out by bad investments or saw their 401(k)s evaporate in the 2008 market crash.

Some hadn’t been able to create enough of a safety net to withstand oth-

erwise survivable traumas: divorce, illness, injury. Others had been laid off or owned small businesses that folded in the recession…Many hoped life on the road would be an escape from an otherwise empty future. (JB, p.57)

But then they found another, supportive, community who had adopted different values altogether. As Bruder quotes one of her subjects, LaVonne, who lived in “LaVanne,”

I found my people: a ragtag bunch of misfits who surrounded me with love and acceptance. By misfits I don’t mean losers and dropouts. These were smart, compassionate, hardworking Americans whose scales had been lifted from their eye. After a lifetime of chasing the American Dream, they had come to the conclusion that is was all nothing but a big con. (JB, p. 150)

These modern nomads have all had to face the basic question, as posed by Bruder: “What parts of this life are you willing to give up so you can keep on living?” (JB, p. 247)

The book is a good read, and should be read before viewing the movie. Bruder’s participation in the culture, albeit with a safety net that others didn’t enjoy, adds credibility to what otherwise could have been just another screed. Her reporting in this book evolved out of the investigations upon which her article, “The End of Retirement: When You Can’t Afford to Stop Working,” was based (1). The movie, which won its Oscar in a down year for films, seems at times like a documentary, but with a focal confusion that could have been avoided by the presence of a Bruder-like character. Perhaps herself.

References

1. Harper’s Magazine, August 2014.

Jacob | Déjà Vu