4 minute read

All Quiet on the Western Front, My Father and Me | Revisiting the Classics, Review by Ernie Stech

[Editor’s note: We introduce this new feature of Emeritus Voices. Readers are invited to submit their impressions of a literature classic that they have recently re-read an extended time after first reading it. Submissions may be up to 2,000 words in length and may include graphics. Please follow the Emeritus Voices submission guidelines as found on the EV website.]

All Quiet on the Western Front

Advertisement

My Father, and Me

Ernie Stech

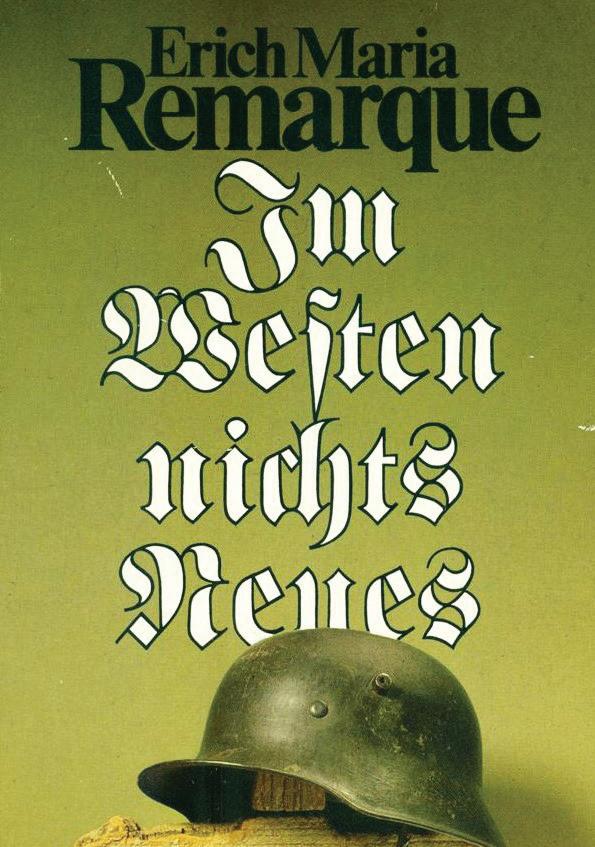

Eric Maria Remarque soldiered in the German army during World War I. In 1928, fourteen years after the armistice, he published Im Westen nichts Neues (In the West there is Nothing New), describing his experiences in the trench warfare against the French. The title was taken from an Army communique. In 1929, it was translated into English and retitled All Quiet on the Western Front. Subsequently, twenty-two translations were published in various languages, and the book sold an estimated 40-60 thousand copies in the 1930s despite being about by then old history. It is in publication to this day including e-book editions with an estimated 2.5 million copies having been sold over ninety years.

My father fought against the French in that war. He served four years, was wounded twice, and taken prisoner. It was a different kind of war against the French in that prisoner exchanges were made. My father twice was sent to Switzerland, back to Germany, and returned to the front lines. After the armistice, he signed on as an ordinary seaman for various firms and toured the world, although not always with the best accommodations. In 1926, he jumped ship in Baltimore, got a job firing furnaces, and eventually moved to Cleveland, Ohio to join his sister and her husband. My father, Ernst Stech,

was engaged, at that time, to Christine Rambow in Hamburg, Germany. She joined him in the U.S. in 1928. I joined them in 1933 when my father was 42 and mother 36.

Ernst never talked about his military experiences. He did have a small wooden box in which he stored the two bullets taken from his body and some other mementos. Eventually, a set of medals awarded to WWI veterans by the Nazi Third Reich were added. Among them was the Iron Cross.

He never spoke to me of his war experiences. His silence was understandable. There was a 42-year difference in age. He could hardly take aside a sixyear-old son and describe the horrors of war.

We had a copy of All Quiet on the Western Front on a bookshelf throughout my childhood. My first reading was when I was 18, the same age as the principal characters in the book. Somehow it had little impact. I was more interested in my own future that did not include military service.

In the many years since, I have read All Quiet five times, the latest just recently. With advancing age, I found the experiences of Paul Baumer, the narrator, more and more horrendous. I became aware over the years that it serves as a window into the life of the nice man I knew as a father. Somehow, he survived and was not psychologically scarred.

All Quiet on the Western Front is not easy reading. It follows four classmates who were trained for military service by their headmaster who was a corporal in the army reserve. The training consisted of continual belittlement and denigration. The intent was to produce men who would not rebel against authority or flee from combat. They would serve because there was nothing else to do. In war, it would be kill-or-be-killed.

In the trenches, the four youngsters suffered from hunger and fatigue. They were subjected to days of artillery bombardment. The German army provided poor rations, often consisting of potatoes.

In a telling scene, one of the four is wounded by artillery shell fragments and must have a lower leg amputated. A troubling injury because his pride and joy were a wonderful pair of boots. He suffered other injuries as well. Visited by his three friends, they understood he was dying. Paul Baumer stayed with him to his last breath. Then Paul had to write a letter to the dead comrade’s mother. Even worse, he had to decide whom among the friends the boots and other possessions should be given.

Reading about that sort of event is depressing. There are many of them. Why, then, go back five times? A major consideration is still the desire to understand what my father went through as a young man. I read All Quiet on the Western Front as a memorial to a father who could not, for various reasons,

Stetch | Revisiting the Classics

Stetch | Revisiting the Classics talk about the exposure to horrors that are best left forgotten.

The book is a way to connect even many years after his death. Thus, it is a solemn obligation. I pay respect and honor to a 42-years-older-than-me father I hardly knew. Thus, the book is a memorial to a man who could not, for various reasons, talk about his exposure to the horrors that existed around him for several years.

Beyond the personal and familial connection, the book always serves as reminder that the people who fight a war are ordinary citizens, in many cases from lower socioeconomic classes. They are trained, organized, and ordered by an elite, the generals and colonels who reside beyond the reach of rifles, artillery, or bombs.

I will continue, each time taking a deep breath, to read this book out of a sense of obligation to my father and a remembrance to all those who serve or served on the front lines of any war, police action, or peacekeeping mission.

If going off the grid is meaningful, there has to be a grid.